Rep:Mod:cc1007

Molecular Mechanics

Introduction

Molecular Mechanics can be used as a more sophisticated and quantitative alternative to plastic or metal molecular 3-dimensional models when attempting to understand how effects such as sterics affect chemical reactivity.[1] However, while the information available from physical models is limited to estimating properties such as molecular strain and stereoselectivity in a very qualitative manner, an appropriate computer programme can offer numerical results which are surprisingly accurate in comparison to experimental data.

This allows direct comparison between the properties of two compounds, but can also offer insights when predicting the most stable isomer of a compound. Molecular mechanics can be a short-cut to the lengthy process of determining structure of a molecule by x-ray crystallography, using relative bond energies to calculate the lowest energy (and therefore most probable) conformation for the molecule.Intramolecular effects can also be calculated, such as measurement of the dihedreal angle between two hydrogen atoms in a molecule (and therefore calculation of coupling constants), or the distance between two atoms, and their steric interaction.

The main constraints to accuracy in Molecular Mechanics are computer power and time. Ideally, the full Schrodinger Wave Equation would be used to calculate the properties of the molecule, but for all except the most simple compounds, this simply takes too long.

Molecular Mechanics works on the assumption that the properties of a molecule can be calculated by summing the individual energies of bonds. There are five main terms in the total energy, taken from the Wiki Page on Molecular Mechanics[2]:

The sum of all diatomic bond stretches (each expressed as a simple Hookes law potential), which account for strain. The sum of all triatomic bond angle deformations (also a simple Hookes law potential), which account for strain. The sum of all tetra-atomic bond torsions (a cosine dependance), which account for strain. The sum of all non-bonded Van der Waals repulsions (using a simple 6/12 potential), which account for steric repulsion. The sum of all electrostatic attractions of individual bond dipoles, which account for hydrogen bonding.

MM2, the interface which will be used to optimise the geometry of the molecule for the majority of the project, works by finding the conformation of the molecule which results in the lowest total energy possible, giving the most thermodynamically stable conformation. However, the main limitation of MM2 is that it cannot predict kinetic products as it does not take transition state geometry into account.

The Hydrogenation of Cyclopentadiene Dimer

1,3 Cyclopentadiene can undergo a [4+2} cycloaddition via a concerted, non bis-percyclic transition state [3] to produce a the endo dimer 2. This is the kinetic product and is produced preferentially to the exo dimer due to stereoelectronics as the transition state leading to the endo product is lower in energy than that producing the exo product[4]. A diagram[5] of the relative exo and endo transition and product energies has been calculated computationally in a recent report[6]. Diels-Alder reaction causes orbitals to be in the configuration to leading to the endo product. To produce the exo product, the reaction would have to proceed via a stepwise biradical transition state instead of a concerted Diels-Alder reaction.

Although the endo transition state is lower in energy than its exo counterpart, the Molecular Mechanics calculation shown below suggests that the exo product, 1, is actually lower in energy by approximately 2.13 kcal than the endo product. Thus, although the endo product is formed under kinetic conditions, the exo product is actually more thermodynamically stable, having less steric strain as the 5-membered ring is orientated in the opposite plane from the bridgehead. This is reflected in the Molecular Mechanics calculations below, as the otrsional strain for Molecule 1 is much larger than that for Molecule 2. This highlights some of the limitations of the Molecular Mechanics system; the fact that transition states cannot be taken into account, and therefore only thermodynamic values can be calculated.

As shown in the Molecular Mechanics table below, Molecule 4 has a lower overall energy than Molecule 3, and therefore is more thermodynamically stable. This is mainly due to the high bending energies of Molecule 3, which are much larger than those of Molecule 4 and outweigh the latter's high torsional energies. This suggests that in a reaction, the double bond in the norborane ring would be reduced preferentially to that in the 5-membered pentane ring, taking into account the assumption that the reaction is under thermodynamic control and reversible. As a hydrogenation, this is not the case. However, in this instance, the Molecular Mechanics method appears to be accurate. According to the literature[7], the double bond in the norborane ring is reduced first to relieve ring strain at the bridgehead, as bonds are more free to undergo rotation. Upon further hydrogenation, the double bond in the 5-membered ring is then reduced. The consecutive hydrogenations are both exothermic, with the first slightly more so than the second. They are -138.8 kJmol-1 and 109.5 kJmol-1 respectively[8].

| Molecule | Total Energy/kcal mol-1 | Stretching Energy/kcal mol-1 | Bending Energy/kcal mol-1 | Torsional Energy/kcal mol-1 | VDV Energy/kcal mol-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 31.87 | 1.28 | 20.56 | 7.66 | 4.23 |

| 2 | 34.00 | 1.25 | 20.88 | 9.51 | 4.29 |

| 3 | 35.94 | 1.25 | 20.85 | 9.50 | 4.30 |

| 4 | 31.15 | 1.09 | 14.54 | 12.51 | 4.51 |

Diagrams of the four molecules in this exercise are shown below. with the top two being the Cyclopentadiene dimers Molecules 1 and 2, and the two underneath the hydrogenated dimers, Molecules 3 and 4.

Stereochemistry of Nucleophilic additions to a pyridinium ring

Reaction A

As shown in the mechanism to the right, Prolinol can undergo nucleophilic attack, reacting with the Grignard reagent methyl magnesium iodide to add a methyl group beta- to the carbonyl carbon, alkylating the pyridine ring. This reaction exhibits excellent regiochemical control with yields of up to 85%; it has been suggested that this is due to the effect of chelation between the magnesium in the reagent and the carbonyl oxygen.[9]

However, more bulky Grignard reagents such as Phenyl-magnesium bromide can demonstrate even higher regioselectivities of up to 99:1. This is likely to be due to the fact that the altermnative site of nucleophilic addition, on the carbon adjacent to the pyridine nitrogen, is sterically hindered by the methyl group on the nitrogen. If the nucleophile is very bulky, it will be even more likely to react to form a product with the regiochemistry shown above, as the alternative pathway would be too sterically hindered.

Likewise, it is highly stereoselective; the Molecular mechanics calculation shown below shows that the lowest energy (and thus most thermodynamically stable) configuration of the product inolves the incoming methyl group bound in the same plane of the ring system to the carbonyl group. However, Molecular Mechanics cannot preduct the energy of the transition state (where we assume the magnesium metal is chelated to the oxygen on the carbonyl) as it does not model high-energy transition states and also cannot recognise Magnesium as an element. Nevertheless, it predicts the same stereospecific product as the literature.[10].

| Molecule | Total Energy/kcal mol-1 |

|---|---|

| 5 | 57.50 |

| 6 | -2.68 |

Reaction B

The pyridinium ring in Molecule 7 can undergo nucleophilic attack with aniline to produce Compound 8. Due to the steric bulk of the phenyl group, the reaction is atropenantioselective, with no free rotation around the C-N bond of the nitrogen nucleophile. Around the nitrogen, only one main conformation can be adopted, which is with the phenyl group pointing away from the carbonyl ring system.

As with the Grignard reaction in the previous section, this Nucleophilic Addition is highly stereoselective, although not for the same reasons. There is no chelation between the amine nucleophile and the carbonyl oxygen; in fact, due to the larger steric bulk of the phenyl amide, the carbonyl lactam directs the nucleophile to the opposite face of the ring.

This is confirmed in the literature by the presence of coupling between the hydrogens of the methyl on the seven-membered ring and those on the carbon adjacent to the nucleophilic nitrogen. Thsi suggests that the amine must have attacked the pyridine ring on the same face as the methyl group, which is the opposite face to the carbonyl lactam.

The Molecular Mechanics calculation predicted this correctly, stating that the most stable product conformation occurs when the carbonyl is pointing down and the NHPh group pointing up. This results in less steric strain, the NHPh nuclephile being much larger than the methyl group of the Grignard reagent used in the previous section.

A second factor to take into account is that of dipole moment. Organic molecules tend to prefer smaller overall dipole moments, and having both C-N and C=O bonds pointing in the same direction would produce a large dipole which would almost certainly destabilise the molecule. Thus, having the groups on different planes results in a more stable conformation.

| Molecule | Total Energy/kcal mol-1 |

|---|---|

| 5 | 99.63 |

| 6 | 38.65 |

Stereochemistry and Reactivity of an Intermediate in the Synthesis of Taxol

Molecules 9 and 10 show key intermediates in the synthesis of taxol. The reaction scheme to the right shows the oxy-cope rearrangement used to produce the two compounds. Although it is usually considered an irreversible process [11], studies have shown that if the products are sufficiently high in energy so that they are thermodynamically energetically comparable with the reactants, an equilibrium between the two tautomers can be achieved.

Molecular mechanics suggests that Isomer 9, with the carbonyl on the top face of the ring and having a higher total energy, shows the kinetic, less thermodynamically stable product. The reason behind its higher total energy is likely to be because the fused cyclohexane ring is locked into a twist-boat conformation, making the molecule very high in energy. It cannot undergo ring-flipping to a lower energy conformation as it is constrained by the bridged cyclononene. [12]

Upon standing, Compound 9 is likely to isomerise to Molecule 10 by rotation of the single bonds in the larger norborane ring. This results in the carbonyl facing with the oxygen on the bottom face of the ring,, which produces the much more stable chair conformation in the fused cyclohexane ring. This is much more thermodynamically favourable, hence its lowered energy.

| Molecule | Total Energy/kcal mol-1 |

|---|---|

| 9 | 59.33 |

| 10 | 55.54 |

Although the alkene is adjacent to a bridgehead and therefore destabilised by strain, literature on hyperstable alkenes[13] suggests that as it is a part of a large ten-membered ring, this strain is reduced and the alkene stabilised. This occurs because the large ring allows more flexibility and can potentially allow flattening of the bridgehead, reducing strain. Likewise, the bridgehead is trans to the ring chain, reducing steric constraints and resulting in a more stable molecule.

Regioselective Addition to 11-chlorotricyclo[4.4.1.01,6]undeca-3,8-diene

Part 1: Observation of Molecular Orbitals

Even in a molecule as seemingly symmetrical as Compound 12, reactivity can be heavily influenced by the electronic density around the molecule. This section of the report explores the corellation between electronic density and regioselectivity.

A more quantum-mechanical approach was used for this section of the report. After determining the most thermodynamically stable conformation of the compound, the MOPAC interface was used the calculate the energy of the molecular orbitals and predict the electron density around the ring. It was used to give a graphical representation of the molecular surface at each energy level. Diagrams of the energy levels around the HOMO and LUMO are shown below, with the blue and red surfaces denoting the presence of electron density.

As observed below, in spite of the high relative symmetry of the molecule as a whole, there is a distinct asymmetry between the pi-bonds in terms of electron density. In the HOMO, most electron density is directed towards the double bond syn- to the chlorine bridge, thus making it an electron-rich double bond likely to act as a nucleophile. [14]. The HOMO of the anti- alkene is much lower in electron density, making it a poorer nucleophile. Another reason for the fact that electrophiles preferentially react with the syn- double bond is the presence of antiperiplanar interactions between the Cl-C antibonding orbital and the HOMO of the alkene anti- to the C-Cl. This stabilises the anti- alkene [15], making it less likely to undergo electrophilic addition.

|

|

|

|---|---|---|

| HOMO-2 | HOMO-1 | HOMO |

|

|

|

| LUMO | LUMO+1 | LUMO+2 |

However, the molecular orbital sufaces above show that alkene anti- to chlorine bond has an empty antibonding molecular orbital in its LUMO while that syn- to the chlorine has none. This suggests that being an electron-poor double bond, it will interact with a reducing agent (such as H2) much more readily than the syn- alkene.

Part 2: Influence of Cl-C bond on the vibrational frequencies of this molecule

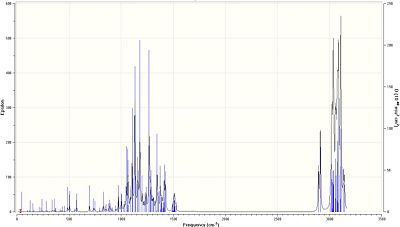

Two molecules were explored in the course of this section; the diene 12, and its hydrogenated product, Molecule 13 as shown in the section above. To calculate their vibrational frequencies, an opt freq calculation was run on the Gaussian interface. The output files were then opened in Gaussview and the range of molecular vibrations explored.

A variety of vibrations were observed, primarily consisting of the deformation, bending, rocking and scissoring of CH and CH2 bonds, as well as ring breathing. However, only the functional group stretches (that of the C-Cl and alkene bonds) were noted.

As observed in the tables below, the C-Cl stretch in Compound 12 had a frequency of 755.95cm-1, while that of the hydrogenated product, Compound 13, had a higher frequency of 774.97cm-1. This suggests that the C-Cl bond is longer and weaker, and thus lower in energy in 12 than it is in 13. This may be due to a variety of reasons including a decrease in the stabilising antiperiplanar interaction between the Cl-C antibonding orbitals and the HOMO of the alkene anti- to the C-Cl orbitals, as mentioned in the section above.

Likewise, the frequency of the syn- C=C bond stretch is higher by around 19cm-1 in the hydrogenated product than in the original diene, suggesting that in the hydrogenated product, the C=C bond is shorter and stronger. This is likely to be due to the removal of the exo alkene bond and its interaction with the C-Cl antibonding orbital, allowing increased orbital overlap and thus stabilisation between the endo alkene bond and the C-Cl antibonding orbital.

| Bond stretch | Frequency/cm-1 | Dipole strength/esu2cm2 |

|---|---|---|

| C-Cl | 755.95 | 28.91 |

| C=C (syn) | 1739.03 | 2.65 |

| C=C (anti) | 1761.57 | 3.22 |

| Bond stretch | Frequency/cm-1 | Dipole strength/esu2cm2 |

|---|---|---|

| C-Cl | 774.97 | 20.91 |

| C=C (syn) | 1758.06 | 4.3314 |

Mini-Project: Formal Synthesis of Porantheridine and its C6-epimer

Introduction

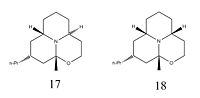

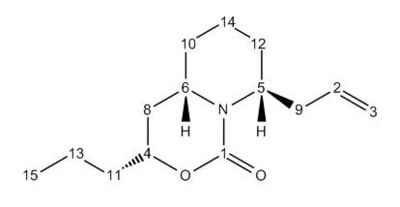

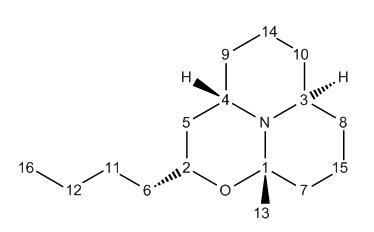

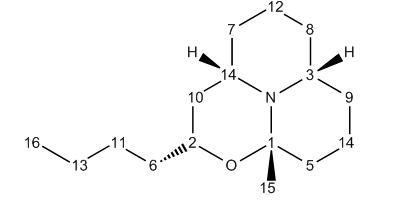

With the increasing interest in stereoselective piperidine syntheses, there have been a number of studies on the synthesis of Porantheridine

[16], Compound 17. It is a highly rigid tricyclic piperidine alkaloid naturally occuring in Porantherida Corymbosa, a low, woody shrub found in New South Wales and Queensland. A full review of its spectral properties was conducted in 1974 by Johns et al.[17]; However, it was only much more recently that its stereoisomer, the Decahydro-9a-methyl-2-propyl-2H-[1,2]oxazino[2,3,4-de]quinolizine epimer, was formally synthesised. This mini-project explores the configurations, calculated spectra and relative energies of the two stereoisomers, as well as some of the intermediates used in their synthesis. These will be compared to the literature values where possible, and an asessment made on the accuracy of the model.

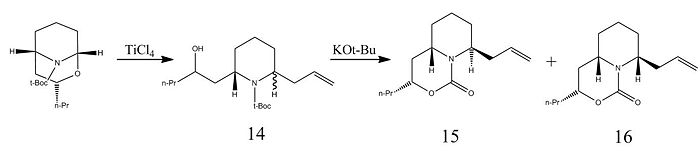

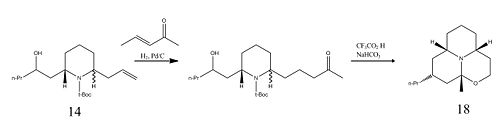

Relative Energies of cis and trans Intermediates

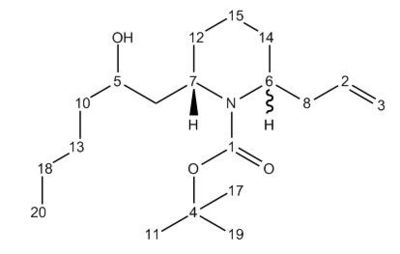

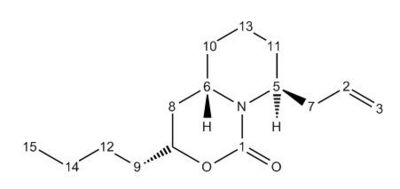

The synthesis of the C6 epimer involves a large number of synthetic steps to ensure high stereospecificity. One intermediate step involves the ring-opening of a bicyclic N,O acetal with titanium tetrachloride and allyltrimethylsilane [18] to produce Compound 12. This is then reacted with a base, KOt-Bu, with removes a tri-butyal protecting group and allows the nitrogen lone pair on the piperidine ring to act as a nucleophile, producing Compounds 15, the cis-isomer, and 16, the trans-isomer. As shown by Molecular Mechanics calculations in the table below, due to the much lower torsion energy, the trans- isomer, Molecule 16, has a lower overall evergy than its cis- conterpart, Molecule 15. This supports the existence of the 9:1 ratio between trans and cis isomers described in the literature[19].

| Molecule | Total Energy/kcal mol-1 | Stretching Energy/kcal mol-1 | Bending Energy/kcal mol-1 | Torsional Energy/kcal mol-1 | VDV Energy/kcal mol-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14 | 47.70 | 2.39 | 14.07 | 22.48 | -6.75 |

| 15 | 26.20 | 1.60 | 5.21 | 3.41 | 14.75 |

| 16 | 24.88 | 1.44 | 9.41 | -0.09 | 4.11 |

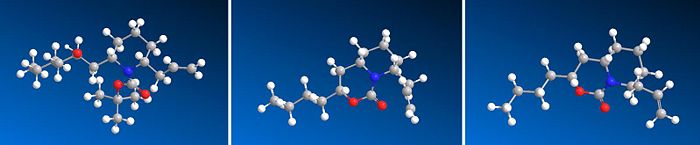

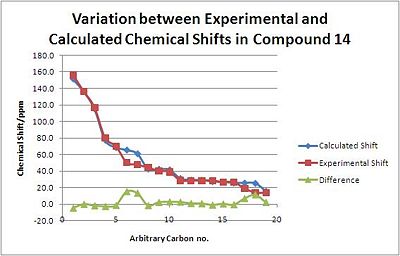

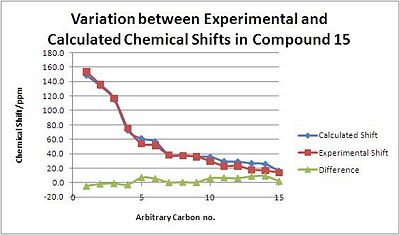

13C NMR of cis and trans intermediates

Molecules 14, 15 and 16 were analysed with the Gaussian interface to produce a GIAO Magnetic Shift, equivalent to an NMR spectrum. The NMR Shift calculation was shown to give good corellation between most the NMR calculated in Gaussview and the experimental NMR spectra provided in the original literature[20]. Shifts with a larger difference than 5ppm between the values calculated and the experimental calculations are highlighted in bold; with these carbon atoms, there is likely to be a difference in conformation between the molecule modelled in ChemBio and the molecule in reality. This is likely to be due to the fact that the these three molecules have a great deal of conformational flexibility and can easily undergo free rotation to change their conformation.

With the starting material, Molecule 14, there is generally good agreement between the Magnetic Shielding shown in Gaussview and the experimental data[21]. The main anomalies are carbon taoms 6, 7 17 and 18, which have abnormally differences in shift value.

| Carbon no. | Calculated Shift/ppm | Experimental Shift/ppm | Difference/ppm | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 151.3 | 155.8 | -4.5 | |

| 2 | 136.2 | 136.1 | 0.1 | |

| 3 | 115.2 | 116.8 | -1.6 | |

| 4 | 77.4 | 79.9 | -2.5 | |

| 5 | 68.7 | 70.0 | -1.3 | |

| 6 | 65.7 | 50.3 | 15.4 | |

| 7 | 61.2 | 47.7 | 13.5 | |

| 8 | 42.8 | 44.2 | -1.4 | |

| 9 | 42.5 | 40.1 | 2.4 | |

| 10 | 41.9 | 39.0 | 2.9 | |

| 11 | 31.4 | 28.7 | 2.7 | |

| 12 | 29.6 | 28.5 | 1.1 | |

| 13 | 29.4 | 28.5 | 0.9 | |

| 14 | 27.7 | 28.5 | -0.8 | |

| 15 | 27.1 | 26.6 | 0.5 | |

| 16 | 26.1 | 26.6 | -0.5 | |

| 17 | 25.9 | 18.9 | 7.0 | |

| 18 | 25.6 | 14.1 | 11.5 | |

| 19 | 16.1 | 13.7 | 2.4 |

With Molecule 15, the agreement is less good, although there it is generally consistent with the literature[22]. This may be because there are now two fused cyclohexane rings locked in conformation, and the conformation chosen in this exercise is simply different to the real lowest energy conformation.

| Carbon no. | Calculated Shift/ppm | Experimental Shift/ppm | Difference/ppm | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 148.7 | 153.3 | -4.5 | |

| 2 | 134.0 | 135.7 | -1.7 | |

| 3 | 115.5 | 116.7 | -1.2 | |

| 4 | 72.7 | 75.4 | -2.7 | |

| 5 | 61.2 | 54.1 | 7.1 | |

| 6 | 56.9 | 51.3 | 5.6 | |

| 7 | 38.4 | 38.1 | 0.3 | |

| 8 | 37.9 | 37.2 | 0.7 | |

| 9 | 36.0 | 35.7 | 0.3 | |

| 10 | 35.7 | 29.5 | 6.2 | |

| 11 | 29.6 | 22.9 | 6.7 | |

| 12 | 29.1 | 22.9 | 6.2 | |

| 13 | 26.7 | 17.9 | 8.8 | |

| 14 | 25.7 | 16.4 | 9.3 | |

| 15 | 16.0 | 13.8 | 2.2 |

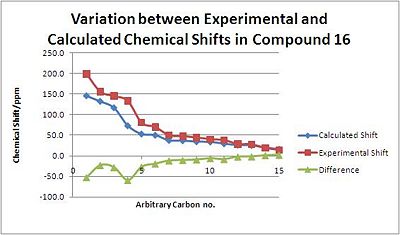

The shifts calculated for Molecule 16, are very similar to those calculated for Molecule 15 due to the similarity of the two molecules; however, they are completely different to the experimental data[23]. It is mainly atoms 1 to 9, those in the cyclohexane rings, suggesting that it is the rings that are in the inocrrect configuration, possibly with a cyclohexane ring in a chair instead of a twist-boat conformation. The Molecular Mechanics energy calculation above showed that the overall energy of Molecule 16 was lower than that of Molecule 15, so the former must be in a more thermodynamically stable conformation.

| Carbon no. | Calculated Shift/ppm | Experimental Shift/ppm | Difference/ppm | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 145.7 | 198.4 | -52.6 | |

| 2 | 132.4 | 155.4 | -23.0 | |

| 3 | 116.7 | 144.9 | -28.2 | |

| 4 | 73.2 | 132.9 | -59.7 | |

| 5 | 53.1 | 80.2 | -27.1 | |

| 6 | 50.2 | 69.6 | -19.4 | |

| 7 | 37.6 | 49.5 | 11.9 | |

| 8 | 36.9 | 47.5 | -10.6 | |

| 9 | 34.5 | 44.7 | -9.5 | |

| 10 | 33.9 | 40.0 | -6.1 | |

| 11 | 29.5 | 37.8 | -8.3 | |

| 12 | 26.1 | 28.4 | -2.3 | |

| 13 | 25.5 | 27.4 | -1.9 | |

| 14 | 19.9 | 18.8 | 1.1 | |

| 15 | 16.1 | 14.0 | 2.1 |

Relative Energies of Porantheridine and its Epimer

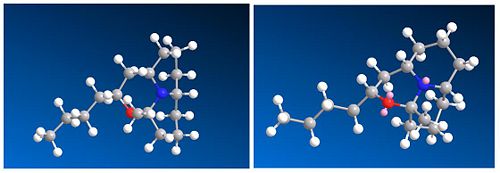

Although the syntheses of the Porantheridine and its C6 epimer require different synthetic pathways, their relative thermodynamic energies when calculated with Molecular Mechanics are actually quite similar. Contrary to the earlier cis and trans intermediates, Molecules 15 and 16, Porantheridine, where the two protons on the carbons adjacent to the central nitrogen are trans, is actually slightly higher in energy. Its epimer is lower in energy mainly because of the reduced strain from the fused cyclohexane ring adjacent to the oxygen atom, which is in a chair conformation in Molecule 18 but a twist-boat conformation in Molecule 17.

| Molecule | Total Energy/kcal mol-1 | Stretching Energy/kcal mol-1 | Bending Energy/kcal mol-1 | Torsional Energy/kcal mol-1 | VDV Energy/kcal mol-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17 | 48.19 | 2.49 | 10.92 | 17.08 | 19.66 |

| 18 | 41.49 | 2.388 | 7.41 | 16.31 | 19.79 |

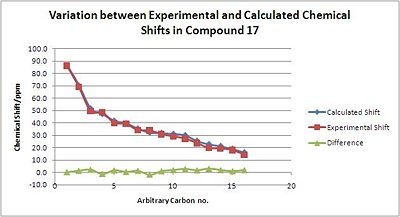

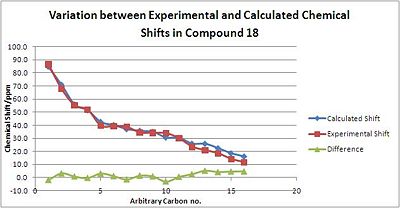

13C NMR of Porantheridine and its Epimer

The product Molecules 17 and '18' were also analysed with the Gaussian interface to produce a GIAO Magnetic Shift, equivalent to an NMR spectrum. The NMR Shift calculation was shown to give excellent corellation with the literature, both for Porantheridine and its epimer. There were no shifts with a larger difference than 5ppm between the values calculated and the experimental data, making a strong case that the conformation of the molecule modelled is in the correct orientation. The rigid fused piperidine rings ensure that the molecules are locked in conformation and cannot undergo ring-flipping or rotation, which is likely to be the reason why the predicted values are so similar to the experimental ones.

As stated above, with the Porantheridine compound 17, there is very good corellation between the NMR shifts produced experimentally and those predicted with the GIAO Gaussian interface. Differences between calcualated and experimental values are generally no larger than 3ppm.

| Carbon no. | Calculated Shift/ppm | Experimental Shift/ppm | Difference/ppm | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 86.5 | 86.2 | 0.3 | |

| 2 | 70.5 | 69.1 | 1.4 | |

| 3 | 51.8 | 49.5 | 2.3 | |

| 4 | 47.2 | 48.4 | -1.2 | |

| 5 | 41.8 | 40.0 | 1.8 | |

| 6 | 39.7 | 39.2 | 0.5 | |

| 7 | 35.5 | 34.1 | 1.4 | |

| 8 | 32.2 | 34.0 | -1.8 | |

| 9 | 31.9 | 30.8 | 1.1 | |

| 10 | 33.8 | 29.1 | 2.0 | |

| 11 | 30.1 | 27.3 | 2.8 | |

| 12 | 25.5 | 23.7 | 1.8 | |

| 13 | 22.8 | 19.7 | 3.1 | |

| 14 | 21.3 | 19.3 | 2.0 | |

| 15 | 19.1 | 18.0 | 1.1 | |

| 16 | 16.2 | 14.6 | 1.9 |

With the Porantheridine epimer 18, the corellation between experimental and predicted values is not quite as good as that for Molecule 17, but they are still better than those predicted in the previous section and differences are no larger than 5 ppm. Most of the discrepancy arises from the carbon atoms with lower shifts. These are mainly in the n-propanyl chain, suggesting that due to its high flexibility, it was calculated to be in a different conformation to its experimental conformation.

| Carbon no. | Calculated Shift/ppm | Experimental Shift/ppm | Difference/ppm | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 84.6 | 86.5 | -1.9 | |

| 2 | 70.9 | 67.8 | 3.1 | |

| 3 | 55.9 | 55.2 | 0.7 | |

| 4 | 51.5 | 51.9 | -0.4 | |

| 5 | 42.6 | 39.6 | 3.0 | |

| 6 | 40.2 | 39.2 | 1.0 | |

| 7 | 37.1 | 38.6 | -1.5 | |

| 8 | 35.8 | 34.4 | -1.8 | |

| 9 | 35.0 | 34.2 | 1.4 | |

| 10 | 30.7 | 33.8 | 0.8 | |

| 11 | 30.5 | 30.0 | -3.1 | |

| 12 | 26.0 | 23.5 | 0.5 | |

| 13 | 25.9 | 20.8 | 2.5 | |

| 14 | 22.5 | 18.4 | 5.1 | |

| 15 | 18.6 | 14.1 | 4.1 | |

| 16 | 16.2 | 11.6 | 4.5 |

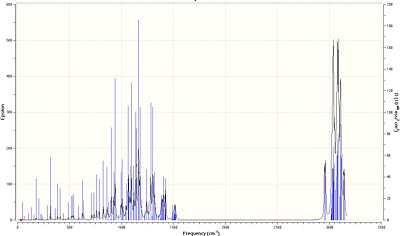

IR Spectra of Porantheridine and its Epimer

As the literature did not provide assignations for its I.R. spectra, the Gaussview interface was used to calculate all the stretches for each molecule and assign the main functional groups.

As shown in the table below, the three C-N bonds are between approximately 1140 and 1165cm-1, which corresponds well to literature values[24].

| Bond stretch | Frequency/cm-1 | Dipole strength/esu2cm2 |

|---|---|---|

| C-N | 1139.58 | 28.43 |

| C-N | 1143.74 | 24.27 |

| C-N | 1163.46 | 54.14 |

| C-O | 1170.09 | 13.06 |

| C-O | 1228.72 | 2.73 |

In comparison to Compound 17, all three C-N stretches in Compound 18 are higher in energy, suggesting a stronger, shorter bond, while the two C-O stretches are lower in energy. However, as it is the amine group which is central to the ring system, this explains the lower energy of the epimer system.

| Bond stretch | Frequency/cm-1 | Dipole strength/esu2cm2 |

|---|---|---|

| C-N | 1269.08 | 28.43 |

| C-N | 1274.27 | 24.27 |

| C-N | 1179.22 | 54.14 |

| C-O | 1131.17 | 34.75 |

| C-O | 1137.27 | 71.36 |

References

- ↑ http://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php/Mod:molecular_mechanics

- ↑ http://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php/Mod:molecular_mechanics

- ↑ P. Caramella, P. Quadrelli, L. Toma, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2002, 124,1130–1131

- ↑ D. H. Ess et al., J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 7586–7592

- ↑ https://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php/Image:Reactivity_Scheme.JPG

- ↑ D. H. Ess et al., J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 7586–7592

- ↑ D. Skala, J. Hanika, Petroleum and Coal, 2003, Vol. 45, 105-108

- ↑ K. Alder, G. Stein, Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem., 1933, 504, 205

- ↑ A. I. Meyers, N. R. Natale, D. G. Wattlaufer, S. Rafii, J. Clardy, Tetrahedron Lett., 1981, 22, 5123

- ↑ A. G. Schlutz, L. Flood, J. P. Springer, J. Org. Chem., 1986, 51, 838-841

- ↑ AR. K. Hill, Comprehensive Organic Synthesis, 1991, Vol. 5

- ↑ S. W. Elmore, L. A. Paquette, Comprehensive Organic Synthesis, 1991, Vol. 5

- ↑ A. B. McEwent, P. Schleyer, J. Am. Chem. SOC. 1986, 108, 3960-3967

- ↑ I. Fleming, Frontier Orbitals and Organic Chemical Reactions, Wiley, 1971, London

- ↑ B. Halton, R. Boeseb, H. S. Rzepa, J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans, 1992, 447-451

- ↑ R. W. Bates, Y. Lu, M. P. Cai, 2009, Tetrahedron, 65, 7852

- ↑ S. R. Johns, A. R. Lamberton, A. A. Sioumis, H. Suares, Aust. J. Chem, 1974, 27, 2025-2034

- ↑ R. W. Bates, Y. Lu, M. P. Cai, 2009, Tetrahedron, 65, 7852

- ↑ R. W. Bates, Y. Lu, J. Chem. Soc, 2009, 74, 9460-9465

- ↑ R. W. Bates, Y. Lu, J. Chem. Soc, 2009, 74, 9460-9465

- ↑ R. W. Bates, Y. Lu, J. Chem. Soc, 2009, 74, 9460-9465

- ↑ R. W. Bates, Y. Lu, J. Chem. Soc, 2009, 74, 9460-9465

- ↑ R. W. Bates, Y. Lu, J. Chem. Soc, 2009, 74, 9460-9465

- ↑ http://www.cem.msu.edu/~reusch/VirtualText/Spectrpy/InfraRed/infrared.htm