Rep:Mod:cb208

Module 1: The Basic Techniques of Molecular Mechanics and Semi-Empirical Molecular Orbital Methods for Structural and Spectroscopic Evaluations

Introduction and Aims

The aims of this project are to investigate the use of molecular modelling in order to determine organic structure and reactivity. This modelling is not only useful for finding and explaining the outcomes of reactions, but can also be used to find improvements to reactions and even can be used to predict new types of reaction.

There are two main methods used in the calculation of optimising molecular geometry to an energy minimum, and then analysing it in terms of bond length, angle strain, steric effects and van der Walls interactions. These methods are the molecular mechanics(MM2 and MMFF94) and the semi-empirical molecular orbital model (MOPAC PM6). Both of these methods will be run using ChemBio3D.

First molecular mechanics will be used to determine the geometry and regioselectivity of various reactions, then semi-empirical methods to investigate regioselectivity and Neighbouring group participation. Concluding in a mini-project to investigate the regioselectivity in the reaction of sydnones and propiolates.

Modelling Using Molecular Mechanics

1. The Hydrogenation of Cyclopentadiene Dimer

MM2 in ChemBio3D Ultra 12.0 (ChemBioOffice 2010) was used for all calculations in this experiment. MM2 is used in preference to MMFF94 throughout because it gives a breakdown of each component in the energy, and so can be used to better compare different molecules. It was found that the total energies calculated for each molecule were almost identical no matter how the initial molecule is drawn, and did not vary significantly when the "Minimum RMS Gradient" was varied.

Dimerisation of Cyclopentadiene

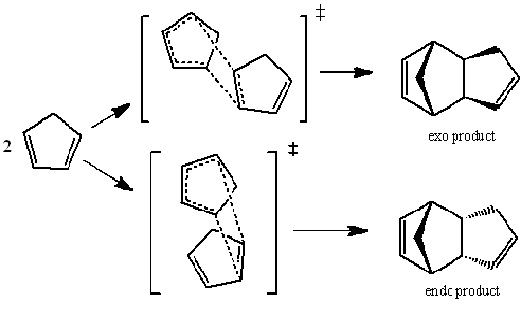

Cyclopentadiene dimerises via a Diels-Alder reaction , this is a [4+2] cycloaddition mechanism and as such has no intermediate species. The transition state of this Diels-Alder reaction contains six delocalised electrons and so has some aromatic character, which stabilises the transition state.

The two possible products of this dimerisation are the exo and endo forms.

In order to find which of the two forms was more stable their energies were calculated.

| Energies (kcal/mol) | Exo Product | Endo Product |

|---|---|---|

| Stretch | 1.2874 | 1.2447 |

| Bend | 20.5941 | 20.8264 |

| Stretch-Bend | -0.8393 | -0.8365 |

| Torsion | 7.6491 | 9.5174 |

| Non-1,4 VDW | -1.4207 | -1.5224 |

| 1,4 VDW | 4.2323 | 4.3236 |

| Dipole/Dipole | 0.3773 | 0.447 |

| Total Energy | 31.8801 | 34.0002 |

These energies show that the exo product is infact the lower in energy than the endo product, and so the more stable form. However, the endo dimer is exclusively formed in the dimarisation, this shows that the reaction is under kinetic control (which is irreversible). Under kinetic control the product with the lowest energy transition state will predominate. The relative energies of the transition states can be understood using two different theories, the endo addition rule and by comparing different resonance structres of the transition states[1]. Alders endo addition rule states that the lowest energy transition state will be when there is a "maximum accumulation of double bonds", causing the endo product to predominate. The resonance structure theory states that one resonance form of each transition state is a zwitterion, and that the endo form is more stable due to the proximity of the two charges in the structure (which cause a stabilizing effect).

Hydrogenation

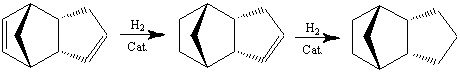

There are two different double bonds present in the endo product produced, either of these could undergo hydrogenation.

Both products 1 and 2 were modelled, and their energies compared to see which was the thermodynamic (more stable) product, and so which bond will be hydrogenated.

| Energies (kcal/mol) | Product 2 | Product 1 |

|---|---|---|

| Bend | 19.818 | 14.5306 |

| Stretch-Bend | -0.8382 | -0.546 |

| Torsion | 10.8217 | 12.5066 |

| Non-1,4 VDW | -1.1994 | -1.0721 |

| 1,4 VDW | 5.6307 | 4.4971 |

| Dipole/Dipole | 0.162 | 0.1407 |

| Total Energy | 35.6989 | 31.1617 |

These results show that product 1 has the lowest energy and so is the thermodynamic product, and most likely product. This is in agreement with results found by Skala and Hanika[2], which also states that product 1 is both the kinetic and thermodynamic product in this reaction. It can be seen that the largest difference in energy between the two products is in the bending energy (19.818 and 14.5306 kcal/mol respectively), this is due to greater ring strain in the norbornene than the cyclopentene double bond. This makes the norbornene double bond more reactive and so hydrogenated more easily, forming product 1.

It has been found[2] that after product 1 has been formed, the cyclopentene double bond can then also be hydrogentated to give a tetrahydro-derivative.

2. Stereochemistry of Nucleophilic Additions to a Pyridinium Ring (NAD+ analogue)

This section investigates two reactions, where the 4 position of a pyridine ring undergoes nucleophilic attack. First attack of N-methyl pyridoxazepinone (5) by methyl magnesium iodide will be studied, and then the reaction between aniline and N-methyl quinolium (7).

MM2 in ChemBio3D Ultra 12.0 (ChemBioOffice 2010) was used for all calculations in this experiment. It was found that using a "Minimum RMS Gradient" of 0.001 was as fast as the default 0.1 and so was used throughout.

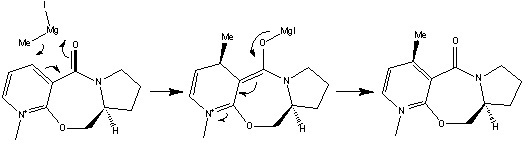

Reaction between N-methyl pyridoxazepinone and methyl magnesium iodide

In this reaction the methyl magnesium iodide is a Grignard reagent, where the methyl group acts as a nucleophile; attacking the pyridine ring both regioselectively and stereoselectively.

Both the regioselectivity and stereoselectivity in this reaction is due to the interaction between the electropositive magnesium on the Grignard and the electronegative carbonyl oxygen on the N-methyl pyridoxazepinone, as found by Shultz et al[3]. This interaction directs the nucleophilic attack from the methyl group to attack the C4 position on the pyridinium ring stereoselectivly. Unfortunately the MeMgI could not be used in the calculations because the magnesium atom is not recognised by MM2.

The stereoselectivity of the nucleophilic attack is determined by the geometry of the carbonyl group.

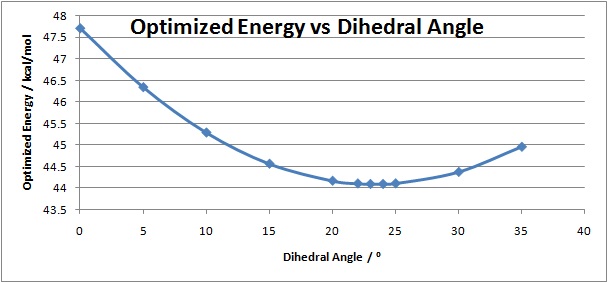

From the above optimized geometry of the N-methyl pyridoxazepinone it can be seen that the carbonyl oxygen is aimed above the planar pyridinium ring. The N-methyl pyridoxazepinone structure was then optimized with respect to the dihedral angle between the carbonyl oxygen and the pyridinium C4 position, to find angle at which the total energy of the molecule is minimal.

| Dihedral Angle / ° | Energy (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|

| 0 | 47.7179 |

| 5 | 46.3475 |

| 10 | 45.2918 |

| 15 | 44.5654 |

| 20 | 44.1687 |

| 22 | 44.1052 |

| 23 | 44.0928 |

| 24 | 44.0933 |

| 25 | 44.1073 |

| 30 | 44.3742 |

| 35 | 44.9593 |

These calculations show that the lowest energy structure of N-methyl pyridoxazepinone is when the dihedral angle is 23°. At this angle the carbonyl is pointing above the plane of the ring, calculations were taken for angles where the carbonyl would be pointing below the ring, but gave far higher energies (at -23° the energy is 55.2341 kcal/mol). These results show that the magnesium atom coordinates to the carbonyl above the plane of the ring. Thus the nucleophilic attack from the methyl occurs on the top face of the pyridinium ring, explaining the stereoselectivity shown in the product molecule.

Reaction between N-methyl quinolium and aniline

This reaction of aniline with N-methyl quinolium is also both regioselective and stereoselective.

In this case the aniline attacks the pyridinium ring at the C4 position as it is the only available point of attack.

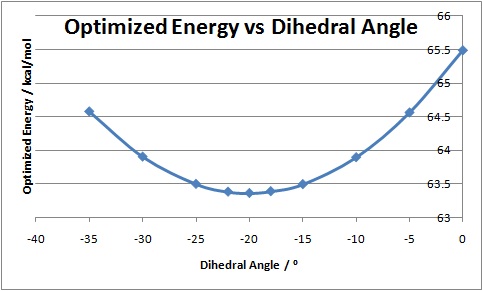

From the above optimized structure it can be seen that the carbonyl in N-methyl quinolium is pointing downwards with respect to the pyridinium ring. Unlike in the previous case nothing in the aniline can coordinate to the carbonyl oxygen, instead attack will occur from the opposite face than the carbonyl due to repulsion between the lone pairs on the aniline nitrogen and carbonyl oxygen. Similarly the structure of the N-methyl quinolium was optimized with respect to the dihedral angle between the carbonyl oxygen and the pyridinium C4 position, to find angle at which the total energy of the molecule is minimal.

| Dihedral Angle / ° | Energy (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|

| 0 | 65.4823 |

| -5 | 64.5579 |

| -10 | 63.8924 |

| -15 | 63.4923 |

| -18 | 63.3875 |

| -20 | 63.3606 |

| -22 | 63.3806 |

| -25 | 63.4963 |

| -30 | 63.9016 |

| -35 | 64.5731 |

These results clearly show that the optimum structure for N-methyl quinolium is when the dihedral angle is -20°, where the carbonyl is below the pyridinium ring. It can clearly be shown that having the carbonyl facing above the ring is unfavoured by the optimized energy of 72.4930 kcal/mol when the dihedral angle is 22°. These findings are in good agreement with those found by Leleu et al[4].

It is very difficult to find the structure with the lowest energy for N-methyl quinolium due to the flexibility of its ring systems.

3. Stereochemistry and Reactivity of an Intermediate in the Synthesis of Taxol

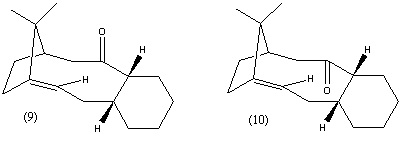

During the synthesis of Taxol both intermediates 9 and 10 are formed, where the carbonyl group is either facing up or down. These two forms are altropisomers, where the steric strain of the carbonyl group restricts the rotation of the single bonds either side of it. It has been found[5] that on standing the altropisomers isomerized to form a single isomer.

The lowest energy conformations for each intermediate were found using MM2 and MMFF94 in ChemBio3D Ultra 12.0 (ChemBioOffice 2010).

| Energies (kcal/mol) | Intermediate 9 | Intermediate 10 |

|---|---|---|

| Bend | 15.8814 | 10.0171 |

| Stretch-Bend | 0.3956 | 0.2824 |

| Torsion | 18.2685 | 19.2847 |

| Non-1,4 VDW | -1.1537 | -1.4567 |

| 1,4 VDW | 12.6882 | 12.6616 |

| Dipole/Dipole | 0.1461 | -0.1887 |

| Total Energy MM2 | 48.898 | 43.1898 |

| Total Energy MMFF94 | 70.5522 | 61.2279 |

These energies show that intermediate 10 is more stable than intermediate 9. The largest difference between the two is in the bending energy, which is significantly higher in 9 than in 10. This difference is due to cyclohexane ring in each molecules, which is in a high energy twisted boat form in 9, but in a lower energy chair conformation in 10. This suggests that intermediate 9 will convert to intermediate 10 when left to stand, which is in agreement with the findings of Paquette and Elmore[5].

When using MMFF94 the relative energies gave similar results, confirming that intermediate 10 is of lower energy than that of 9. Results were about 20 kcal/mol higher than that of the MM2 method, which is due to the different calculations used by each method.

The intermediates are examples of hyperstable alkenes[6], due to the highly stable bridgehead alkene. The stability of hyperstable alkenes arises from their negative olefin strain energy, which makes them much less strained than the equivalent saturated bonds. This negative olefin strain energy makes the hydrogenation of hyperstable alkenes very difficult and slow, because the alkane formed would have far higher levels of strain than the alkene. The bridgehead also helps to sterically protect the alkene from attack.

Modelling Using Semi-empirical Molecular Orbital Theory

The biggest limitation of molecular mechanics is that it does not take electrons into account during its calaculations. This section uses semi-empirical molecular orbital theory to demonstrate the effect electrons have on bonds and spectroscopic properties of a molecule.

In order to find the molecular orbitals of 9-Chloro-1,4,5,8-tetrahydro-4a,8a-methanoaphthalene (12) ChemBio3D Ultra 12.0 (ChemBioOffice 2010) was used, first with the MM2 calculations to minimise the energy, then MOPAC/PM6 to find the molecular orbitals.

When calculating the vibrational frequencies first the geometry was optimized using MM2 then MOPAC/PM6, a Gaussian input file was then created (to run B3LYP/6-31G). This was submitted to SCAN and the results read out using Gaussview 3, Gaussview 5 was found to be too slow to use (15 mintues just to load a file).

4. Regioselective Addition of Dichlorocarbene

Orbital Control of Reactivity

Orbital control of reactivity is shown well by the reaction of 9-Chloro-1,4,5,8-tetrahydro-4a,8a-methanoaphthalene (12) with dichlorocarbene. This reaction was found to be regioselective by Halton et al.[7], where addition was seen to be almost exclusivly across the syn alkene (72%), forming the mono-adduct endo product, and the di-adduct (23%). Addition across the anti alkene (exo product) was not observed.

The reactivity (and so regioselectivity) of molecule 12 can be found using its molecular orbitals, the most important of them being the HOMO and LUMO. The optimization using MOPAC/PM6 gave a heat of formation of 19.73986 kcal/mol.

|

|

|

|

|

The HOMO orbital clearly shows the majority of electron density being present on the syn alkene, with very little electron density on the anti alkene. This makes the syn alkene much more nucleophilic than the anti, and the electrophilic dichlorocarbene will attack the syn rather than anti alkene. This is the main reason why the syn product is produced and not the anti product.

The HOMO-1 orbital shows the majority of its electron density on the anti alkene, but because the HOMO-1 is of lower energy than the HOMO orbital it is less likely to react, again showing why attack on the anti alkene is not favoured.

An antiperiplanar interaction can be seen between the C-Cl σ* orbital in the LUMO+1 and the anti alkene π orbital in the HOMO-1. This interaction causes a stabilizing effect which makes the anit alkene lower in energy than the syn alkene, and is in agreement with the findings of Halton et al[7].

This explains why only the syn and di-adduct products are observed, as any electrophile which would react with the anti alkene would have first reacted with the higher energy syn alkene.

Vibrational Frequencies

The vibrational frequencies of the C-Cl bond and both the syn and anti alkene bonds were calaculated.

| Molecule 12 | C-Cl | Syn Alkene | Anti Alkene |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecule 12 | 770.91 | 1757.36 | 1737.11 |

| Monoalkene | 780.06 | 1753.76 | N/A |

| OH Substituted | 781.16 | 1757.65 | 1797.55 |

| BH2 Substituted | 761.46 | 1758.25 | 1604.48 |

| SiH3 Substituted | 767.94 | 1754.90 | 1633.81 |

| CN Substituted | 772.64 | 1757.13 | 1670.46 |

The vibrational frequencies of C-Cl were found to be in the region of 770cm-1, which is in good agreement with their expected position[8]. The alkene vibrational frequencies were found to be higher than those expected from literature[8] (1640-1680cm-1. This suggests a more stable, stronger bond (higher wavenumber gives a stronger bond), however is also partly to do with the electron withdrawing effect from the Cl and the antiperiplanar stabilization interaction discussed above.

From looking at vibrational frequencies molecule 12 it can be seen that the anti alkene (1737.11cm-1) is lower than that of the syn alkene (1757.36-1). This surprisingly suggests that the anti alkene is less stable than the syn, which is in disagreement with the previous arguments. This can be explained by looking at the π electrons on the anti alkene, some of the electron density is withdrawn from the bond by the C-Cl. This reduction in π electron density makes the anti alkene bond more stable and less reactive, this is because it now has more σ character (π electrons are less stable than σ electrons). This stability causes the anti alkene to have a lower vibrational frequency.

In order to further this experiment the substituents on the anti alkene were varied, and the effects on the C-Cl and both C=C vibrational frequencies were analyzed. The substituents used were OH, BH2, SiH3 and CN.

It can be seen from the table above that the vibrational frequencies of both the C-Cl and syn alkene remained fairly constant regardless of the substituents on the anti alkene, this shows that the strength of the syn alkene is unaffected by the anti alkene.

However, the anti alkene vibrational frequencies are significantly affected by changes in substituent. Only the OH group strengthens the bond (increases wavenumber), this is because the oxygen atom is able to donate electron density to the C=C bond through resonance. The CN group is weakens the bond by withdrawing electron density (lowering the wavenumber), but has a smaller effect than that of the BH2 and SiH3 groups. Both of these groups act as a Lewis acid and so accept electrons from the C=C bond into their unoccupied p/d orbitals, weakening the C=C bond. The effect is larger for BH2 than for SiH3 because the boron p orbitals are better at accepting electrons than the silicon d orbitals (which are higher in energy).

The vibrational frequencies calculated in this experiment are relatively inaccurate due to the calculations basing them on a harmonic oscillator (not on real anharmoic stretches), and through using a relatively small basis set. To improve the accuracy an anharmonic oscillator with a larger basis set could be used, but the computing power and time required for that would be too much for an undergraduate lab.

Structure Based Mini Project

Many synthetic reactions produce a mixture of products, which are often isomers. Studying the mechanism by which a reaction occurs can be an effective way to determine which isomers should be more favoured, but more quantitative means must be used to confirm the products formed. Spectroscopic techniques, particularly NMR, are useful for determining which products have been formed, but now computational analysis is becoming ever more useful in this area.

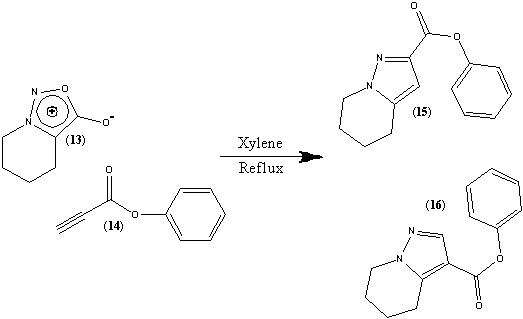

Regioselectivity in the Reaction of Sydnones and Propiolates

Introduction

Pyrazoles are important because of their biological activity[9], particularly as herbicides[10].

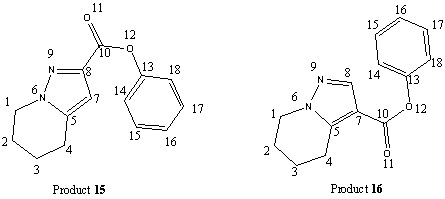

In this experiment the 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction of sydnones with propiolates will be investigated, specifically the reaction of tetrahydropyridino[1,2-c][1,2,3]oxadiazolone (13) with benzyl-propiolate (14). This reaction is known to produce two regioisomeric products, benzyl 3-carboxypyrazole ester (15) and benzyl 4-pyrazolecarboxylate (16), which can be easily separated by silica gel column chromatography. It is known that product (15) is the major product with (16) the minor product[11], in a 2.2:1 ratio[12] as determined by 1H NMR.

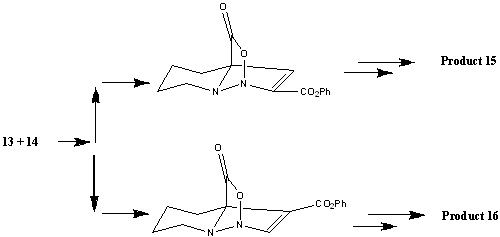

Reaction Mechanism

The reaction between reactants 13 and 14 proceeds through a[4+2] cycloaddition mechanism with the loss of CO2, in which the propiolate can be added in two possible ways[13].

By comparing the energies (found using MM2) of the two different intermediates it can clearly be seen why product 15 is the major product, with its intermediate having an energy of 62.44 kcal/mol which is far lower than the equivalent of product 16 (159.34 kcal/mol).

Structure Optimization

In order to optimize the structure of both products ChemBio3D Ultra 12.0 (ChemBioOffice 2010) was used, first using MM2 then MOPAC/PM6, followed by a final optimization using Gaussian (mpw1pw91/6-31g(d,p)). Due to the relative rigid nature of both products there are few conformations possible, making them good molecules to use in the optimization process.

It can be seen from the optimized structures of both products that the main difference between them is the orientation of the benzene ring relative to the sydnone and pyridine rings. Product 15 has the benzene ring pointing downwards with a dihedral angle between the carbonyl and benzene ring of -147°, while in product 16 it is relatively planar with a dihedral angle of 0°.

Looking at the optimized energies (from MM2) of the two structures it can be seen that product 15 (24.51 kcal/mol) is slightly more thermodynamically stable than 16 (25.46 kcal/mol).

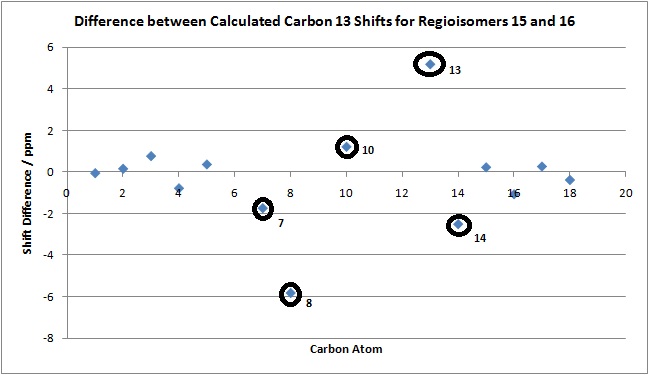

13C NMR

The Carbon-13 NMR was predicted for both product isomers using the GIAO method (mpw1pw91/6-31(d,p) in Gaussian), with chloroform as the solvent. It is expected that these spectra should differ between the two isomers, and so be used to differentiate between the two possible products. Unfortunately the literature[12] was not assigned and had one less carbon peak than expected, and so only nine of the literature peaks could be matched to those calculated (leaving 5 that did not match). This could suggest that the optimized structures are slightly different to those actually formed.

| Carbon Atom | Product 15 | Product 16 | Literature 15 | Literature 16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 48.88 | 48.93 | 48.57 | 47.79 |

| 2 | 24.42 | 24.26 | 22.5 | 22.29 |

| 3 | 22.14 | 21.37 | 20.12 | 19.23 |

| 4 | 24.68 | 25.46 | 23.14 | 22.78 |

| 5 | 137.06 | 136.69 | 140.35 | 142.02 |

| 8 | 137.64 | 143.47 | 136.05 | 140.16 |

| 10 | 157.4 | 156.18 | 162.24 | 162.25 |

| 15 | 126.37 | 126.14 | 128.27 | 128.24 |

| 17 | 125.71 | 125.44 | 128.02 | 127.81 |

| Do not match with literature | ||||

| 7 | 107.68 | 109.42 | 66.2 | 65.13 |

| 13 | 152.1 | 146.9 | 106.01 | 127.7 |

| 14 | 116.93 | 119.44 | 128.28 | 135.88 |

| 16 | 120.19 | 121.26 | 218.44 | 218.43 |

| 18 | 116.81 | 117.19 |

NMR data for product 15: DOI:/10042/to-7355 and product 16: DOI:/10042/to-7356

It can be seen from the above graph the at biggest differences in shift are seen for C(7), C(8), C(10), C(13) and C(14), and so these peaks are best used to identify between the different regioisomers. Carbons 7 and 8 are expected to vary between isomers because they are the two different positions where the ester group can be attached. Carbons 10, 13 and 14 have different shifts for the different isomers because of the different orientation of the benzene ring in each isomer.

The differences present between the calculated and literature shifts here could be due to a variety of reasons. The most important of which is the fact that the calculations were done on a static molecule with no conformational flexibility, while experimentally the molecule would be constantly changing its shape and structure.

1H NMR

The 1H NMR was calculated in the same way, and again the literature[12] was found to have different number of peaks to the number expected. The literature for product 15 had 16H assigned and product 16 12H assigned, while 14H were expected. The peaks were also mostly given as ranges, a combination of these two factors again made comparison between calculated and experimental spectra hard.

| Carbon Atom | Product 15 | Product 16 | Literature 15 | Literature 16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21 | 1.92 | 2.08 | 1.83-2.05 (6H) | 1.8-2.08 (4H) |

| 22 | 1.87 | 2.1 | ||

| 23 | 1.92 | 1.82 | ||

| 24 | 1.69 | 2.05 | ||

| 25 | 2.99 | 2.9 | ||

| 26 | 2.79 | 3.64 | ||

| 19 | 3.77 | 4.09 | 4.19 (2H, t J=5.7) | 4.14 (2H, t J=5.7) |

| 20 | 3.81 | 4.29 | ||

| 5.36 (2H) | 5.26 (1H) | |||

| 6.52 (1H) | ||||

| 27 | 7.02 | 8.15 | 7.27-7.45 (5H) | 7.26-7.42 (5H) |

| 28 | 7.62 | 7.49 | ||

| 29 | 7.83 | 7.85 | ||

| 30 | 7.5 | 7.63 | ||

| 31 | 7.56 | 7.81 | ||

| 32 | 6.97 | 7.99 |

From the table above it can be seen that hydrogens 21-24, 19/20 and 27-31 are in agreement with the peaks from literature, but no match was found for the literature peaks between 5 and 6 ppm. This relatively poor fit between experimental and calculated shifts is likely to be due to the lack of conformational flexibility in the calculated molecules, along with the poor accuracy of the methods used to predict 1H NMRs. Another downfall of these predicted NMR is that no multiplicities are shown, however coupling constants can be calculated using "Jannochio". Only one coupling constant was provided in literature (J=5.7Hz), and so only this constant was calculated, and was found to be identical in both cases.

It can be seen that the greatest shifts are seen for hydrogens 27 and 32. Hydrogen 27 is either on carbon 7 or 8 depending on the regioisomer, and so its change in shift can easily be identified due to it either being on the adjacent atom to a nitrogen (C(8)), or further away C(7). However, the optimized structures must be used to explain the difference in shifts for hydrogen 32 (which is on C(18)), it can be seen that in product 15 that hydrogen 32 is not relatively close to any functional groups, but in product 16 is very close to the carbonyl oxygen, with which it can interact and so change its shift.

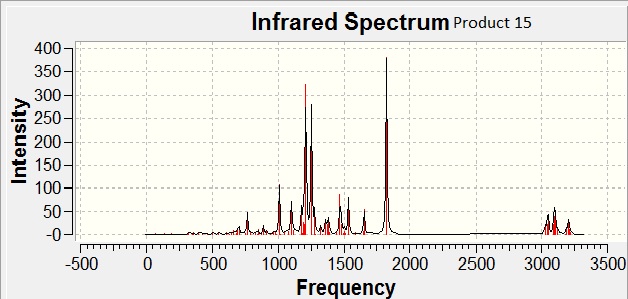

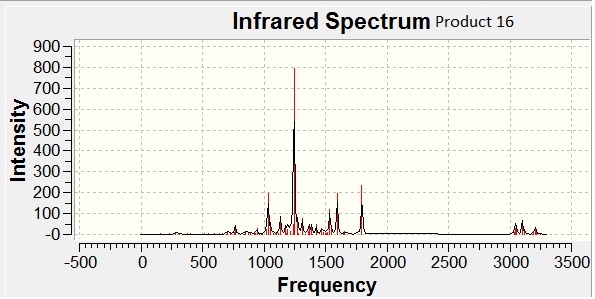

IR Spectra

The IR for both regioisomers were calculated using Gaussian (# b3lyp/6-31G(d,p) opt freq).

IR is a poor method by which to compare regioisomers, due to error of upto 8%, which is greater than the slight changes in the wavenumbers of vibrational frequencies between regioisomers.

However, as expected, the calculations do suggest that product 15 has a much higher carbonyl stretch (1825 cm-1) than product 16 (1729 cm-1).

Conclusion

This experiment showed both the usefulness and limitations of computational techniques in predicting the product regioisomer in reactions. Molecular mechanics and semi-empirical molecular orbital theory calculations are both useful in predicting the outcomes of reactions, and their various spectra. However, due to the relatively new nature of computational chemistry the methods are limited by their equations, in order to be able to truly predict the outcomes of reactions these limitations need to be reduced.

References

- ↑ Sauer, J. Sustmann, R. ""Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1980, 19, 779-807[1]

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Skala, D. Hanika, J. Petroleum and Coal. 2003, 45(3-4), 105-108[2]

- ↑ Shultz, A. et al. J. Org. Chemistry, 1986, 51, 838[3]

- ↑ Leleu, S. et al. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry, 2004, 15(24), 3919-3928[4]

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Elmore, S. Paquette, L. Tetrahedron Letters, 1991, 32(3), 319-222. [5]

- ↑ Camps, P. et al. Tetrahedron, 1997, 53(28), 9727-9734. [6]

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Halton, B. et al. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2, 1992, 4, 447-448.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Infrared Spectroscopy Correlation Table [7]

- ↑ Katritzky, A. Rees, C. Comprehensive Heterocyclic Chemistry, 1984, 5, 169 [8]

- ↑ Munro, D. US Patent 5262388, 1993[9]

- ↑ Gotthardt, H. Reiter, F. Chem. Ber., 1979, 12, 1193.[10]

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 Jung No, L. et al. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc., 2000, 21(8), 761 [11]

- ↑ Ranganathan, D. Bamezai, S. Tetrahedron Letters, 1983, 24(10), 1067-1070 [12]