Rep:Mod:brapbrap2

Module 1 - Organic: Mini Project

Click Chemistry

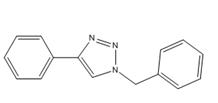

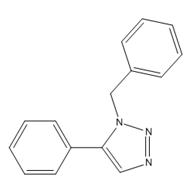

The term click chemistry was one coined by Nobel Laureate Barry Sharpless to describe rapid chemical reactions which are specifically designed for their favourability in order to rapidly and accurately combine two fragments together forming one molecule. Such processes are generally employed with the use of a catalyst which gives this high rate of reaction. In the following interesting study it was suggested that with Cu(I) and Ru(II) catalysis two different regioisomers were obtained. With Cu(I) catalysis the 1,4 isomer predominates, where as under Ru(II) catalysis we see the 1,5 isomer dominating. This intriguing result was modelled computationally to assess whether the original assignment was indeed accurate.

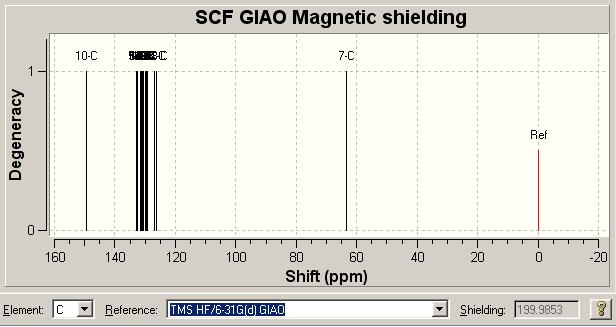

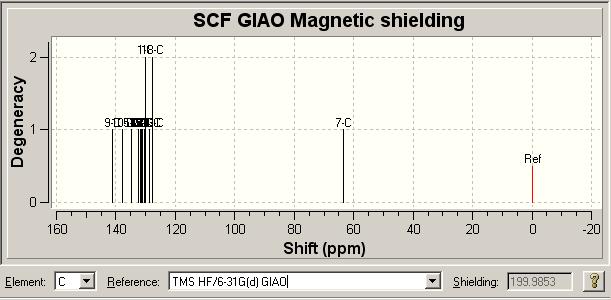

It was possible computationally to generate predicted spectra for the so-called "1,4" (shown as A) and "1,5" (shown as B) products, which could then be compared to the spectra reported in the literature.

| Molecule "A" | Molecule "B" |

|

|

| Cu(I) Catalysis | Ru(II) Catalysis |

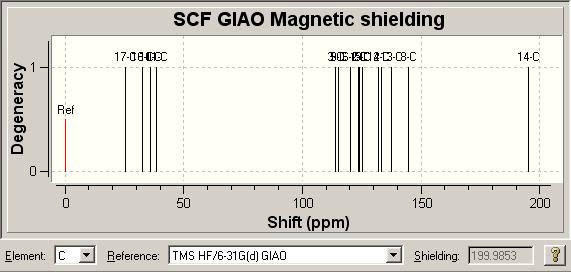

It was possible by the use of the SCAN supercomputer to optimise the geometry of the molecules to such an extent that the NMR spectra could be determined. The results are shown and discussed below. The spectra were generated by the Gaussian program and in all cases done using the TMS HF/6-31G(d) GIAO approximation.

13C NMR Literature [1] Comparison for A | ||||||||||

| Literature δ/ ppm | 119.5 | 125.5 | 127.9 | 128.56 | 128.64 | 128.9 | 130.4 | 134.6 | 148.0 | |

| Model δ/ ppm | 126.388 | 126.902 | 128.182 | 129.081 | 129.859, 129.765, 129.719 | 130.544, 130.419 | 131.509, 131.26, 130.917 | 132.972, 132.598 | 149.467 | |

Here we see a relatively satisfactory correlation between our predicted NMR spectra and that which was obtained by the experimental work of the authors in question. We do, at some points, see that a number of computed values are chosen to correlate to the literature values; this is a technique employed when it was felt more than one of the computational values could correlate to the literature value.

The proposed explanation for this is the higher precision of the computation which will see each peak individually, as opposed to combining signals together. In essence this is due to the fact that the computation can distinguish two signals at a much higher resolution than an NMR spectrometer. As the literature gives no indication of the integration of the peaks we cannot be sure if in fact that multiple signals we see are in fact shown as one higher intensity signal in the literature NMR and so corroboration of this interpretation is not possible.

13C NMR Literature [2] Comparison for B | ||||||||||

| Literature δ/ ppm | 126.93 | 127.22 | 128.22 | 128.92 | 129.08 | 129.64 | 133.26 | 133.34 | 135.66 | 138.26 |

| Model δ/ ppm | 127.548 | 127.567 | 128.867 | 130.319, 130.041, 130.998 | 131.369 | 131.771 | 132.358, 132.265 | 134.767 | 137.825 | 141.007 |

Again we see a good correlation between the literature and our computation. We again find similar issues with the second spectrum as we had with the first, notably a number of peaks associated with certain chemical shift values. Again the proposed explanation is that this is due to peaks being combined into one signal due to the lower resolution of the NMR spectrum in comparison with the computational study.

Having generated spectra it must be remembered that the main purpose of this is to distinguish between the different isomers effectively, and so while our computational spectra agree with the literature spectra, for them to be useful they must differ from each other.

In looking at the two spectra we see a number of peaks around similar chemical shift values and so at first it does appear difficult to tell the two spectra apart. We do however see one major noticeable difference, that being the highest chemical shift observed which is almost 8ppm higher in isomer A than in isomer B, from this we can tell the two isomers apart very easily, making the spectral study of these compounds useful for distinguishing between the two isomers.

The reason for this very useful difference is explained by taking into account the environment and planarity of the isomers. Isomer A clearly has the two sterically bulky phenyl groups kept far away from each other, allowing the phenyl group and the triazole ring to maintain an almost co-planar geometry, giving a high degree of conjugation and so inferred stability in the molecule. In contrast isomer B has the two bulky phenyl groups in close proximity to one another and so we see a significant deviation from planarity between the phenyl substituent and the triazole ring and as such a reduced amount of conjugation.

The result of this effect can be seen in the chemical shift of the carbon attached to the triazole ring. In A this carbon experiences a large amount of aromaticity, resulting in a large shift to a higher ppm. In B due to the aforementioned reduction in the conjugation the effect is smaller and so this carbon atom is found at a lower shift. This is a non-negligible difference and so can be noticed when comparing the spectra allowing one to be distinguished from the other with relative ease, and fairly quickly.

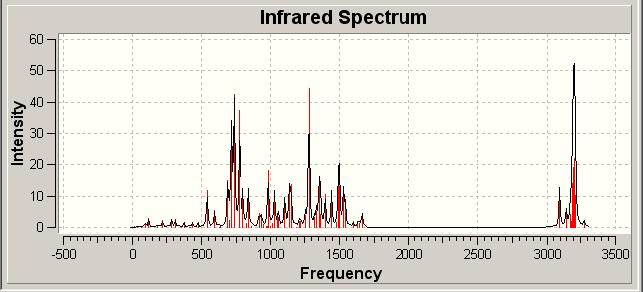

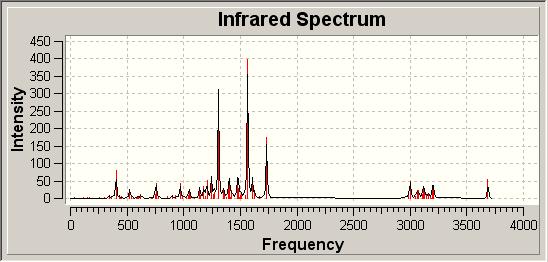

Infrared Spectra of Click Isomers | |||

| |||

| A | |||

| |||

| B | |||

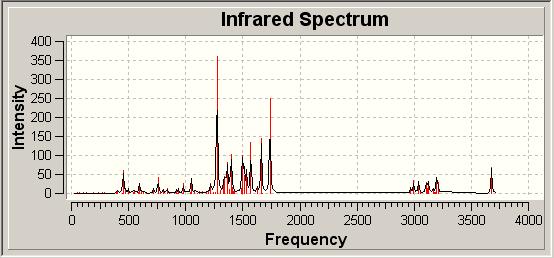

The infrared spectra of the isomers was computationally determined in a rather speculative sense in order to see if any difference in the molecules could be observed. In looking at the spectra disappointingly, but somewhat predictably, we see no real difference between the two isomers.

This is not unexpected due to the very limited difference in the connectivities and functionalities displayed in each isomer. Hence the spectra are similar, meaning IR is not a suitable technique for distinguishing between these two regioisomers, especially in a laboratory experiment where subtle differences may be lost in the limits of the equipment employed.

The final data to compare is the calculated energies which are 3.0478 kcal/mol for A and 6.0838 kcal/mol for B. Though these are estimated values they do show a number of points. Primarily that A is more stable than B, a piece of data which again highlights the importance of the relative proximity of the two sterically bulky groups. Additionally this suggests that A may be the thermodynamic product while B is the Kinetic product, formed by a lower energy pathway overall. This brings up questions of whether conversion between isomers is possible, though this is purely speculative at this stage and would require a substantial amount of further study and modelling.

To conclude this study somewhat it has, in my opinion, been demonstrated that computational NMR studies are very useful in experiments such as that which the original paper was based. As the technique is relatively simple to employ once the method is understood and takes relatively little time, this could be a valuable technique in such studies.

Establishment of Configuration in Diels Alder Adducts by NMR Spectroscopy[3]

A Diels-Alder Cycloaddition is well known to give two possible diastereomeric products, these being the so called endo and exo products, in most cases the endo isomer predominates though exceptions to this rule are well defined and discussion of such rules is well documented.

A major issue with these processes is actually establishing the configuration of the product made, in essence posing the question how does one distinguish between what are very similar structures. Various methods have been put forward with some great success, one very interesting method is that described by Fraser who took advantage of the different effect of a magnetically anisotropic double bond in an exo system compared with an endo system. Specifically in an exo configuration the double bond displays a paramagnetic effect while in an endo configuration a diamagnetic effect is observed. This clearly generates different spectra which allows the different configurations to be distinguished from one another.

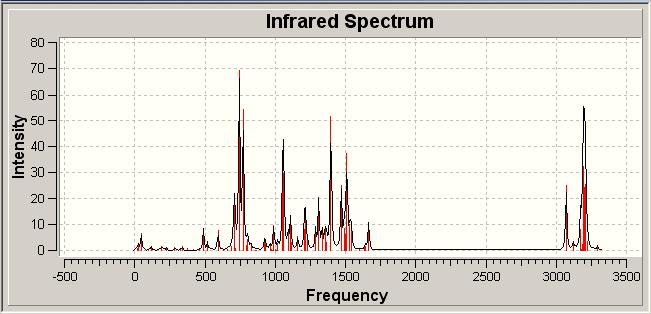

The use of NMR spectroscopy is now widespread in structural characterisation. One fairly recent paper in this area studied "The Regioselectivity of Intermolecular Diels-Alder Cycloadditions of 1-Methylpyrano[3,4]Indol-3-one and the N-Acetylated Derivative". The basic scheme of the study is given below[4]:

|

The suggestion of the authors of this paper is that though in principle there are two possible regioisomeric adducts shown by 4 and 5 in the scheme in the final product we see evidence of only one of these in the final NMR spectrum of the product. It is the intention of this study to generate predicted NMR spectra of these two products and then compare these with the experimental results in order to determine if indeed only one of the products is present.

The relative energies of the two possible products does suggest that molecule 3 is of lower energy than molecule 8, these are shown in the below table.

| Molecule "8" | Molecule "3" |

|

|

| 11.5062 kcal/mol | 7.3590 kcal/mol |

As was shown for "Click" Chemistry, NMR spectroscopy is a very useful technique in distinguishing between isomers. The authors of this paper cite the use of NMR spectroscopy as the main technique in establishing the configuration of the product in a Diels Alder reaction.

NMR spectra were generated computationally for both potential molecules, with the intention of then comparing these with the literature spectrum to establish which molecule was indeed formed.

13C NMR [5] Comparison

| Literature δ/ ppm | 18.42 | 25.04 | 28.40 | 30.49 | 109.95 | 111.66 | 117.80 | 121.30 | 122.30 | 125.69 | 128.69 | 132.82 | 136.83 | 145.71 | 197.89 |

| Molecule 3 Model δ/ ppm | 25.4447 | 28.78 | 34.8538 | 35.2556 | 113.857 | 115.312 | 120.353 | 123.585 | 123.824 | 125.121 | 131.956 | 133.468 | 137.5 | 144.556 | 199.496 |

| Molecule 8 Model δ/ ppm | 25.4467 | 32.6103 | 35.9814 | 38.5097 | 114.026 | 119.534 | 122.433 | 122.59 | 125.636 | 125.809 | 131.19 | 133.504 | 134.835 | 139.753 | 194.96 |

Looking at the two spectra, the spectrum for molecule 3 agrees much more closely with the literature spectrum than molecule 8. As was true for click chemistry the most important thing is how we can distinguish between the two molecules in their spectra to enable us to quickly decide which molecule has been synthesised.

The spectra are in fact quite similar, which is not wholly surprising due to the high similarity of the two molecules. The main difference between the two molecules is the position of the methyl group so this could be a good way to tell the molecules apart, however when we look at the relative chemical shifts the results are somewhat disappointing. The literature cites this as 25.04 and the computation gives molecule 3 at 25.4447 and molecule 8 at 25.4467, as such we have no real way of telling the two apart.

We could also look at the ketone carbonyl carbon; literature gives this at 197.89 while the computation gives 199.496 for molecule 3 and 194.96 for molecule 8. This is a very similar situation to click chemistry and so we could probably tell the two spectra apart by this very high chemical shift peak due to the molecule 3 being twice as close to the literature value. This is not, in contrast to the click chemistry case, be a very definitive distinction between the two spectra.

An interesting point is the position of the C(O)CH3 peak, which literature reports to be around 18ppm, where as computational studies give this at around 35ppm. This is quite a difference and so leads us to question the assignment of the original authors, though without further study it is not possible to criticise the original paper.

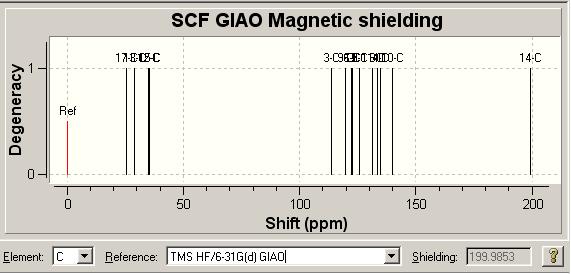

| Molecule "3" | Molecule "8" |

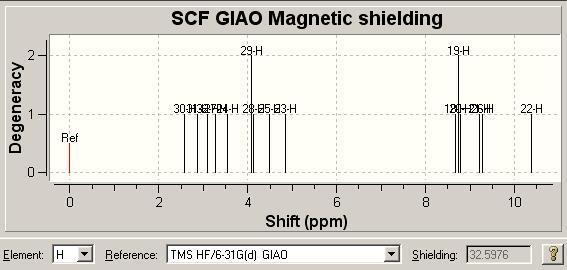

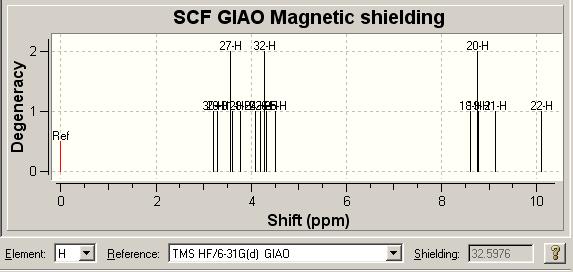

|

|

Above are spectral representations of the computationally predicted NMR spectra. As was the case with the Click Chemistry Isomers the reference used with Gaussian to generate the NMR Spectrum was TMS HF/6-31G(d) GIAO.

It is also possible to look at the proton NMR spectra of such compounds computationally. The main issue with this is the well known limit of this model being of the order of 1-2ppm, which is a very significant amount in proton spectra. This means the relevant information which can be abstracted from proton spectra is somewhat limited.

However due to the similarity of the 13C spectra, the proton spectra were generated to see if we could find a more definite distinction between the molecules. The computation data is shown below.

1H NMR [6] Comparison

| Literature δ/ ppm | 1.35 | 2.46 | 2.65 | 3.02 | 3.12-3.23 | 7.17-7.25 | 7.35-7.38 | 7.64-7.67 | 7.78 | 8.54 |

| Molecule 3 Model δ/ ppm | 2.5772, 2.87602 | 3.12886, 3.26677 | 3.56559 | 4.07128, 4.11725, | 4.48502, 4.85279 | 8.67421 | 8.73537, 8.77985 | 9.20793 | 9.28021 | 10.3754 |

| Molecule 8 Model δ/ ppm | 3.207, 3.29106 | 3.56424, 3.60626 | 3.77438 | 4.08958, 4.19465 | 4.27871, 4.32074, 4.50986 | 8.60758 | 8.74831 | 8.77986 | 9.13478 | 10.1049 |

It is fair to say the two computational spectra are very similar, both with respect to the literature as well as compared to each other. The major difference we see is the noticeably better fit of the spectrum of molecule 3 to the literature values at low chemical shift.

The main use of the proton NMR spectrum in the literature is for its multiplicities, which are not present in the modelled spectra and so as such this immediately limits the spectra. As such aside from saying that molecule 3 does fit the data slightly better we are no further forward in distinguishing between the molecules definitively.

| Molecule "3" | Molecule "8" |

|

|

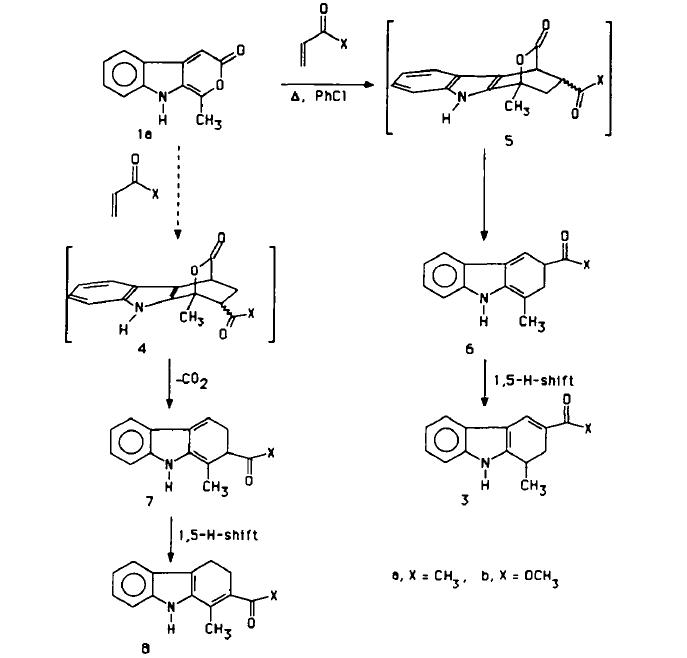

A further widely used technique for structural determination is IR spectroscopy, which again can be modelled computationally. As the original authors submitted IR data, we may be able to distinguish which molecule is formed by looking at the computational infrared spectra. These are given as follows:

Infrared Spectra of Possible Products

|

| 3 |

|

| 8 |

The literature quotes the Infrared Spectrum in CHCl3 with the following absorptions:

| Literature νmax/ cm-1 | 3460 | 3200-3350 | 1636 | 1605 |

In looking at the computationally generated spectra and the literature report of the spectrum we see the same peaks in all three spectra, though with differing intensities. As in the case of the click chemistry the IR spectra are very similar and so are of little use in distinguishing between the two different isomers with any great confidence.

Finally we can look at the relative energies for the two different molecules to give us a guide as to which is more stable, and so potentially more likely to be formed. The energy of 3 is 7.3590 kcal/mol while the energy of 8 is 11.5062 kcal/mol. This energy difference of 4.1472 kcal/mol is significant and suggests that molecule 3 is, as was reported by the original authors, more favourable than molecule 8.

To conclude by looking at the spectra and the free energy of the two possible molecules, we can agree that molecule 3 is formed as this is the lower energy product and matches the literature spectra more closely. Despite this we cannot immediately tell one isomer from the other by the spectra and so the power of the computational study is less prevalent in this second study than in the Click Chemistry example.

NMR Spectroscopy is now a very widely used technique in order to establish isomerisation and configurations. Looking through the literature one finds a plethora of similar studies such as the related use of NMR spectroscopy in positional analysis of natural products and their synthetic equivalents, such as studies on triacyl glycerols[7], Fatty Acids[8] and Natural Oils[9].

References

- ↑ Sirion and Bae, Ionic Polymer Supported Copper(I): A Reusable Catalyst for Huisgen's 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition, Thieme, Supporting Information Used DOI:10.1055/s-2008-1078245

- ↑ Sirion and Bae, Ionic Polymer Supported Copper(I): A Reusable Catalyst for Huisgen's 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition, Thieme, Supporting Information Used DOI:10.1055/s-2008-1078245

- ↑ R. Fraser, Canadian Journal of Chemistry, 1960, 40, 78-84[1]

- ↑ R. Fraser, Canadian Journal of Chemistry, 1960, 40, 78-84[2]

- ↑ H. Nandin de Carvalho et al, Tetrahedron, 1990, 46, 16, 5523-5532 DOI:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)87750-4

- ↑ H. Nandin de Carvalho et al, Tetrahedron, 1990, 46, 16, 5523-5532 DOI:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)87750-4

- ↑ P. R. Redden, Chemistry and Physics of Lipids, 1996, 79, 9-19 [3]

- ↑ G. Vlahov, Magnetic Resonance in Chemistry, 1998, 36, 359-362 [4]

- ↑ G. Vlahov, Magnetic Resonance in Chemistry, 2001, 39, 689-695 DOI:10.1002/mrc.929