Rep:Mod:boulty2

Module Two - Bonding (Ab initio and density functional molecular orbital

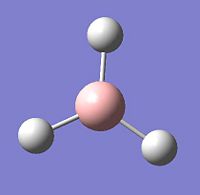

BH3 - borane

BH3, known as "borane", is the most simple trivalent borohydride species, well known for its Lewis acidic properties. Gaussian can be used to perform a multitude of calculations on the molecule of which I will be investigating its dimensions (bond distances / angles), molecular orbitals (MO's) leading to its subsequent behaviour as a Lewis acid and its vibrational modes resulting in its IR spectrum. All calculations were performed using an optimised molecule of BH3.

Optimisation

A BH3 molecule was created in the Gaussview interface and bond lengths changed to 1.50A, which is a value much greater than the literature values suggest. The B atom was fixed at the centre of the molecule with the H atoms moved accordingly so that the distance between the two atomic centres was 1.50A. This was repeated for all 3 B-H bonds. This allows Gaussview to minimise these bond B-H bond lengthsn along with the H-B-H angle into the optimum position for the given electronic configuration. The BLYP method and 3-21G basis set was used to perform this optimisation. The basis set determines the accuracy of the optimisation and this basis set used represents a "low" accuracy method. A more accurate optimisation would require a larger basis set, which is very time consuming. There is a fine balance which musty be achieved between the size of the basis set and the computational difficulty. For more complex molecules, the basis set may have to be increased, but the time to perform the calculation increases. For the BH3 molecule, the results of the optimisation are shown along with the optimisation summary provided by Gaussian

:

| BH3 bond distance / A | BH3 bond angle / degrees | |

|---|---|---|

Experimental |

1.19 |

120.0

|

Literature |

1.17[1] |

120.0

|

However, in the output for the optimisation of the BH3 structure, Gaussview provides us with 4 different structures with varying bond lengths and in some instances with no bonds at all. This is because Gaussview draws bonds based on distance criteria. Classically, a chemical bond can be seen as the resulting interaction between the pairing of electrons by adjacent atoms of the molecule. The final structure in the optimisation procedure has the most negative energy.

Molecule |

Stetching (str)

|

|---|---|

|

|

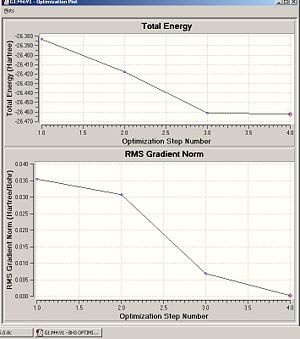

This can also be shown by the optimisation plots. The optimisation procedure can be explained in terms of PES (Potential Energy Surfaces) and the Born Oppenheimer approximation. The B.O. approximation assumes that the positions of the nuclei are fixed and the energy of the system is dependant on the static position of the nuclei. Gaussian reperesents all of the nuclear positions by a collective co-ordinate r, with the potential energy of the system being represented by V(r). If the nuclei are moved from slighly from these 'static' positions, the collective co-ordinate of these nuclei also has to change. e.g. r changes to r'. This will also change the potential energy of the system to V(r') due to a change in the electrostatic interactions between the nuclei. This can be represented by a simple PES. Nuclear-nuclear repulsion increases when the nuclei are at short distances from each other which increases the potential energy of the system. The potential of the system is also increased when the nuclei are pulled apart as they dissociate and no longer form a bond. There is an equilibrium position between these two situations which the optimisation parameter of Gaussian tries to find as it represents the minimum energy of the system. Gaussian solves for different values of r. When the program sees a minimisation trend, it will move in this direction until a minimum energy is found and the r0 bond distance will be found. This can cause some problems in complicated PES's as Gaussian can get caught in potential wells which sometimes do not represent the true minimum energy of the system. When the nuclei and electrons are in equilibrium, there is a balance of forces therefore the first derivative dE/dr must be equal to 0. This is what the optimisation parameter tries to find (when not in equlibrium dE/dr does not equal 0. Shown (left) are the results from the total energy plot of each optimisation step and the RMS (Root Mean Squared) gradient plot. The total energy plot shows Gaussian traversing the PES of BH3, finding the minimum energy structure which it converges to on its 4th attempt. The RMS gradient shows that dE/dr tends towards 0 as the equilibrium structure for the system is found. The optimised structure is the most stable strcuture in the gas phase or in the solid state with no solid state forces present.

Molecular Orbital Analysis

In order to obtain the MO's for BH3, the electronic structure must be solved. To achieve is the Gaussian methodolgy must be changed. The method was changed from 'Optimisation' to 'Energy' but the basis set was kept the same. These are the quantitative or computed MOs which we can compare to the qualitative or approximate MOs produced via MO diagrams The NBO paramter was also used in these calculations which has two main functions. The NBO paramter can indicate charge distribution within the molecule. In the MO pictures below produced by Gaussian, the bright green shading indicates highly positive charge whereas the bright red charge indictaes highly negative charge.

From acid/base chemistry we would expect the boron to be Lewis deficient and highly positively charged. This is shown in the NBO log file, where the boron is assigned a charge of + 0.332 and each hydrogen -0.111. The NBO analysis also partitions the electron density of the whole molecule out into atomic orbital like orbitals which are then used to form 2c-2e bonds. It can be used to show us what proportion of each bond is made up from boron atomic orbitals and hydrogen atomic orbitals. For example, the B-H(2) bond shown is made from 44.48% boron orbitals (33.3% s and 66.7% p) and 55.2% hydrogen orbitals (100% s). This now shows nicely that the BH3 moecule is made from three sp2 hybrids with an empty p-orbital perpendicular to the plane of the molecule. In the NBO analysis this is represented by the orbital with the lowest occupacny (as it is unoccupied) and the lowest energy. Orbital 8 matches well with these features, but the energy is negative. This gives us infromation about the acidic nature of the orbital as unoccupied orbitals usually give a positive energy, but this p-orbital will accept electron density in a Lewis acid fashion. Overall it can be noted that the NBO analysis takes the delocalsied MO picture and places into a 2c-2e bonding picture.

BH3 pop file. https://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/a/a5/BH3_POPtom.LOG

The first 8 MO's of BH3 were computed using Gaussian with the results shown below with the comparison to the LCAO method of obtaining MO's also shown. The LCAO (Linear Combination of Atomic Orbitals) allows us to simplify the MO picture for BH3 and construct the MO's from their AO fragments (H3 and B). A typical MO for the trigonal planar BH3 is also shown below, constructed using ChemDraw.

| Number | Orbital Symmetry | Energy | Gaussian Representation | MO diagram representation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

1 |

a1' |

-6.730 |

Core-like (spherical 1s orbital)

| |

2 |

a1' |

-0.518' |

||

3 |

e' |

-0.357 |

||

4 |

e' |

-0.357 |

||

5 |

a2 |

-0.075 |

||

6 |

e' |

0.189 |

||

7 |

e' |

0.189 |

||

8 |

a1' |

0.192 |

The MO's predicted by Gaussian get more delocalised as they get higher in energy as they are unoccupied. The occupied orbitals are contracted and are found relatively close to the centre of the molecule. As shown in the table above, the MO's predicted by the LCAO approximation are in bery good agreement with those computed experimentally.

Vibrational Analysis

The vibrational spectrum of BH3 can also be considered using Gaussian. The second derivative of the V(r) vs. r is the basis of the frequency analysis. If the frequencies are all positive then the second derivative represents a minimum but if one of them is negativem a transition state is present. If more than one value is negative then the optimisation has failed or a critical point has failed to be reached. The analysis also provides the IR and Raman modes which can be compared to experimental values. The same basis set was used for these calculations as before with the energy of the system also remaining the same (-26.46 a.u.). This is shown by the summary of the vibrational analysis. Each molecule has 3N-6 vibrations and the frequencies listed above as the "low freqeuncies" are the -6. These ideally should be close to 0 but my analysis showed the largest 0 frequency to be -66.8cm-1. The animated vibrations predicted by Gaussian are shown below with the corresponding IR spectrum with the corresponding log file also given: https://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/2/25/TOMBOULTWOOD_B3H_FREQ.LOG

| Number | Form Of The Vibration | Description | Frequency | Intensity | Symmetry D3h Point Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 |

Wagging motion of the B-H groups. Perpendicular displacement of the B-H groups with respect to the plane of the molecule. |

1144 |

93 |

a2

| |

2 |

Scissor like motion of two of the B-H bonds. Movement of 2 B-H bonds in a scissor like fashion with one B-H bond remaining in the same position with displacement occuring in the plane of the B-H bond. |

1203 |

12 |

e'

| |

3 |

The BH2 unit performs a scissor like motion as shown in vibration 2, but now the other hydrogen performs a wagging motion. |

1203 |

12 |

e'

| |

4 |

This is a totally symmetric stretch with the central B atom remaining motionless in the centre of the molecule. The three hydrogens stretch with the same amplitude, symmetrically resulting in no overall chnage in dipole moment and zero intensity in the IR spectra. |

2598 |

0 |

a1'

| |

5 |

Antisymmetric stretch. This time one of the H's is stationary with movement from all of the other atoms. |

2737 |

104 |

e'

| |

6 |

Similar asymmetric stretch to that observed in 5, but all atoms move with different amplitudes in different directions. |

2737.44 |

104 |

e'

|

Even though Gaussian predicts 6 different vibrations, it is evident that only 3 appear in the spectrum. If we consider Vibration 4, we can see that this is a totally symmetric vibration and there is no overall change in dipole moment. For a vibration to be active, there must be a change in dipole moment - so this is not seen in the spectrum. There are alos two sets of degenerate vibrations with symmetry e' - giving two sets of peaks.

BCl3 - boron trichloride

When treating second row elements such as chlorine, a more improved basis set must be used alongside pseudo potentials. Polarization functions allow the electron density to become polarized to one side of a molecule. Both types of function are important for an accurate description of most inorganic molecules where the electron density is moving around. The BCl3 molecule was first optimised using the DFT method (B3L9P) with the LANL2MB basis set used which represents a medium level basis set. The optimisation gives the B-Cl bond to be around 1.87A, with the Cl-B-Cl being 120 degrees as expected due to its trigonal planar geometry. The energy was minimsed to -69.44 a.u. with the RMS gradient being normalised to almost 0. This is again shown using the summary table.

.

Vibrational analysis

The symmetry of the molecule was restricted to D3h with the tolerance altered to very tight (0.0001). The same basis set was used for the freqeuncy calculations and the energy was minimised to the same value. Similarly with the BH3 molecule, there are 3 peaks in the IR spectrum due to the presence of two sets of degenerate peaks and one of the vibrations exhibiting a zero dipole moment rendering the vibration IR inactive. The log file is given below: https://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/3/3e/BLC3_TOM.LOG

| Number | Form Of The Vibration | Frequency | Intensity | Symmetry D3h Point Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

1 |

214 |

4 |

a2

| |

2 |

214 |

4 |

e'

| |

3 |

377 |

44 |

a2

| |

4 |

417 |

0 |

a1'

| |

5 |

939 |

259 |

e'

| |

6 |

939 |

259 |

e'

|

Isomers of Mo(CO)4L2

The geometries of the cis and the trans form of Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 will be firstly optimised using the ChemScan function as the calculations will take too long just using the provided software. A B3LYP method will e used with a low level basis set and pseudo potential of LANL2MB to get the rough geometry of the structure. A loose convergence was also set by adding opt=loose to the additional parameters. However in the optimised files, the P-Cl bonds disappear.

| cis-Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 DOI:10042/to-4417 | trans-Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2DOI:10042/to-4418 |

|---|---|

This is due to internal problems with Gaussview. Gaussview has an internal list of bond distances and when the optimization is computed, the new P-Cl bonds are outside of the Gaussview range so the program does not put them in. Optimisation with this low level basis set can normally generate good apprximations of the bond lentgths and angles. The dihedral angles however are not so well described in the rotation of the PCl3 groups. If the molecule is not in the correct orientation to begin with, the optimization of the energy can get caught in potential wells that do not lead to the correct energy optimization and the ultimate minimum of the system. Therefore the correct orientation has been provided to avoid this problem. For the cis-complex, the optimized LANL2MB structure will be altered so that one Cl atoms in the P-Cl bonds points up so that it is parallel to the axial bond and one of the other Cl atoms points downwards. For the trans-complex both the PCl3 groups will be orientated so that they are eclipsed and one Cl atom of each PCl3 groups lies parallel to one of the Mo-C bonds. Both of the isomers will now be optimized using a more complex basis set, LANL2DZ instead of the LANL2MB basis set used previously. Once optimised, these structures were sent for frequency analysis using the same basis set and methodolgy.

Optimised structures:

Looking at the energies of the two optimised complexes, the trans complex has an energy of -623.58 a.u. (-1.64 x106 kJ/mol) whereas the cis complex has an energy of -623.58 (-1.63 x106 kJ/mol). This shows the complexes are relatively simialr in energy but the cis complex shows slightly more stability that the trans complex (2.7kJ/mol more stable). This is a relatively small energy difference which means that the effects making one stable more than the other is only a small overriding effect. Literature studies on Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2, show that the cis form is electronically more stable than the trans form in the gas phase [2]. When the ligands around the metal centre are small, the cis conformer is nearly always favoured with electronic stabilization effects dominating steric effects. However as the PR3 groups increase in steric bulk, there is a shift in preference from the cis conformer to the trans conformer as the steric effects override the electronic stabilisation effects. The data obtained from the computational experiment is in good agreement for when the PR3 groups are small with the cis conformer being preferred, i.e. being lower in energy compared to the trans product. The theory behind this extra stability of the cis form is due down to backbonding effects from the d-orbitals of the Mo transition metal. In the trans complex, the CO ligands can backbond with the metal centre to equal effect as the PR3 groups. This results in less overall stabilisation of the attached PR3 groups due to the competing nature of the CO ligands. In the cis complex there are less competing effects with more opportunity for backbonding for the PR3 ligands giving the complex more overall stabiltiy compared to the trans. Looking at other geometric features of the two molecules, the two Mo-P bond lengths can be compared in the trans and cis complex. In the cis complex, the Mo-P bond length is 2.51A and in the trans complex the Mo-P bond length is 2.45A. Literature values for these bond lengths are 2.52A for the cis complex[3] and 2.50A for the trans complex. The experimental data is in good agreement with that obtained in the literature which shows that the correct conformers have been found in the optimization process. Bond angles in both complexes are all approximatley 90 degrees which shows near perfect octahedral co-ordination of the complexes.

Vibrational Analysis - trans complex

The vibrational analysis for the trans complex along with its resulting IR spectrum are shown below. As expected, the trans complex only gives one disticnt CO stretching freqeuncy in the spectrum although there are four separate carbonyls in the complex. Vibration modes 42 and 43 both give high intensity peaks so we would expect to see both these CO stretches in the spectrum but they both appear at similar frequencies so only one stretch is seen. Vibration modes 44 and 45 are both assigned to CO stretches but these both occur at very low intensities so are not visible in the spectrum. The stretching frequencies can be compared to literature values provided by M. Y. Darensbourg and D. J. Darensbourg. M. Y. Darensbourg and D. J. Darensbourg state that there is one expected trans-CO stretching frequency due to group theory considerations and in a hydrocarbon based solvent they give the stretching frequency to be 1943.1cm-1[4]. However it must be noted that these stretching frequencies relate to PR3 where R=OC6H5, so a direct comparison cant be made but as both R groups (Cl and OC6H5) are EWG's, I would expect similar frequencies for the Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 complex.

| Vibration Number | Form Of The Vibration | Description | Frequency | Intensity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

42 |

a2 |

1950 |

14751

| ||

43 |

a2 |

1950 |

1467

| ||

44 |

a2 |

1977 |

1

| ||

45 |

a2 |

2031 |

4

|

Vibrational Analysis - cis complex

The vibrational analysis for the cis-complex along with its resulting IR spectrum are shown below. As expected, the cis complex gives four distinct CO stretches in the IR spectrum compared to the one stretch in the trans-spectrum. All the vibration modes appear at different frequencies and all at a high intensity so all of the vibrational modes are visible in the spectrum. The stretching frequencies can be compared to literature values provided by M. Y. Darensbourg and D. J. Darensbourg. M. Y. Darensbourg and D. J. Darensbourg state that there are four expected cis-CO stretching frequencies due to group theory considerations and in a hydrocarbon based solvent they give the stretching frequencies to be 2049 cm-1(s), 1965 cm-1(vs), 1947.5 cm-1(vs) and 1941 cm-1 (which is only seen under high resolution conditions[5]. However it must be noted that these stretching frequencies relate to PR3 where R=OC6H5, so a direct comparison cant be made but as both R groups (Cl and OC6H5) are EWG's, I would expect similar frequencies for the Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 complex. This same consideration must be taken into account when assessing the trans literature stretching freqeuncies.

| Vibration Number | Form Of The Vibration | Description | Frequency | Intensity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

42 |

a2 |

1945 |

737

| ||

43 |

a2 |

1949 |

1498

| ||

44 |

a2 |

1958 |

632

| ||

45 |

a2 |

2023 |

598

|

Vibrational Analysis - Low frequencies

The vibrational analysis for the low frequencies are shown below. The low frequencies are given for the cis and trans complex for the stretching frequencies below 20cm-1. From the vibration diagrams, the vibrations occur in a multitude of directions at extremely low intensity. This suggests that these vibrations could be induced thermally.

| Vibration Number | Form Of The Vibration | Description | Frequency | Intensity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 (trans) |

a2 |

5 |

0

| ||

2 (trans) |

a2 |

6 |

0

| ||

1 (cis) |

a2 |

11 |

0

| ||

2 (cis) |

a2 |

18 |

0

|

Ammonia boranes and their analogues

Introduction

Ammonia-boranes are the topic of extent research due to their ability to store hydrogen and in a reversible process release this stored hydrogen. This has the important consequence of ammonia boranes being condsidered as potential fuels as hydrogen is now being considered the "fuel of the future". However there have been many problems desigining suitable ways of storing this hydrogen - with ammonia borane being used as a possible solution due to its stability at room temperature. Ammonia borane contains 19.6% hydrogen by weight and releases more than two thirds of this below 150 degrees which makes it an ideal candidate for fuel storage[6]. The aim of this project will be to computationally compare the electronic properties of ammonia borane and its analogues with their organic derivatives such as ethane. The molecules I will be considering are ammonia borane, ethane, borazine and benzene. I will then investigate the effect of substitution on the borazine ring on its reactivity by assessing the molecular orbital diagrams of the associated HOMO's and LUMO's.

Optimisation, Structure and Energy Considerations

All of the molecules were firstly drawin in GaussView and optimised using the ChemScan service. A relatively simple basis set was used as the molecules do not demand large time consuming basis sets due their non complexity and no inclusion of TM's (Transiton metals) or atoms bonding using d-orbitals. The DFT B3LYP method was used with the relatively simple 6-31G basis set in the optimization process. The optimised structures are shown below with Jmol illustrations and their energies shown in kJ/mol (with accompanied DOI's).

| Eclipsed Ethane | Staggered Ethane | Eclipsed AB | Staggered AB | Benzene | Borazine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staggered Ethane DOI:10042/to-4472 | Eclipsed AB DOI:10042/to-4468 | Staggered AB DOI:10042/to-4469 | Benzene DOI:10042/to-4470 | Borazine DOI:10042/to-4471 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Energy / a.u. |

-79.84 |

-83.25 |

-83.22 |

-232.26 |

-242.68

|

Energy / kJ/mol |

-2.09 x 10^5 |

-2.19 x 10^5 |

-2.19 x 10^5 |

-6.10 x 10^5 |

-6.37 x 10^5

|

As shown above, ammonia borane can be considered in its "eclipsed" form and its "staggered" form. This is the same case with the conformations of ethane with the energy difference between these two conformers being referenced as around 12kJ/mol. Optimisation of these conformers can has been undertaken and one can decide which of the conformers is the most stable and therefore the most dominant structure. The staggered conformation for the ammonia borane structure can be considered the most stable structure, of which the same can be said about the staggered ethane conformer. This is due to steric clashes (synperiplanar interactions) between hydrogens in the eclipsed form of both structures raising the energy of the conformers compared to their staggered conformers. Both the elcipsed and staggered conformations of ammonia borane have similar B-H and N-H bond lengths (N-H - 1.02 (S), 1.02 (E), B-H - 1.21 (S), 1.21 (E) ). This is the expected trend as they are both just rotational conformers. However the calculated B-N bonds for both conformers differs by around 0.03A, with the literature value for the staggered conformation mathcing that obtained experimentally - 1.67A[7]. This could be due down to the unfavourable intramolecular interactions in the eclipsed form as discussed above. However it must be noted than the N-B bond in the solid phase has been measured as considerabley shorter than that in the gas phase - 1.58 vs. 1.67 A. This is thought to due down to enahnce charge transfer effects in the more polar medium of the solid vs. gas phase[8]. The B-H and N-H bond lengths are in good agreement with literature values, (B-H - 1.16A, N-H 1.03A)[9]. Literature values suggest that the optimisation has optimised the structurs to their lowst energy conformations due to these well matched bond lengths but only the vibrational analysis will tell us this for sure. NBO analysis can also be undertaken on the staggered ammonia borane structure to show the orbital composition of the N-B bond and how the charge density is spread around the molecule.

This calculation was performed at the same time as the optimisation process using the NBO parameter and full NBO analysis being used. The makeup of the B-N bond suggests a highly polarised B-N bond, which can be identifeid before this analysis using resonance type structures. The nitrogen provides 81.96% of the bonding orbitals (contributing orbitals: 35.25% s, 64.75% p), with the boron only providing 18.04% (contributing orbitals (19.35% s, 80.34% p). This percentage analysis suggests a dative bond between the nitrogen and boron. More interestingly, the contributing orbitals from the boron are mainly p-orbitals. As the bond is mainly dative in character, we would expect donation of electron density from the nitrogen into vaccant orbitals on the boron, which are usually low lying p-orbitals. This is suggested by the NBO analysis but an MO analysis would confirm this. From the JPEG images shown of the NBO analysis, bright green represents highly positively charged and red represents highly negatively charged. As expcted due to the datvie bond nature of the N-B bond, the boron atom and its three hydrogens are all highly negatively charged due to the acceptance of a lone pair of electrons from the nitrogen atom. The H atoms attached to boron are hydridic and those attached to nitrogen are somewhat acidic.

For comparison a LANL2DZ basis set was also used to see if the results obtained would change and they did. The B-N bond was optimised to 1.69A, B-H bond to 1.21A, and N-H 1.02A. In comparison to the more basic basis set of 6-31G, the more in depth basis set increased the bond distances but actually put them further away from the literature values which shows that a more in depth basis set is not always the correct choice. A full summary of the optimisation can be found here. DOI:10042/to-4620

Considering the borazine structure, it is isoelectronic to that of beznene but the difference in electronegativity of boron and nitrogen has some consequences on bond lengths compared to benzene. As suspected, being isoelectronic to benzene, borazine shows a degree of deleoclaisation of electron density around the central B-N atoms. This will be shown later by MO analysis. From a structural perspective, this can be seen by the same B-N bond length around the ring of 1.43A. Comparing this to the B-N bond length in ammonia borane (1.67A to 1.69A), there is a significant reduction which shows a degree of delocalisation. To see where this bond length fits, a theoretical molecule containing a B=N bond has been produced which shows a B=N bond length of 1.36A. The B-N bond length fits somewhere inbetween these two values which shows that these bonds both have single and double bond character which is characteristic of a delocalised system. The calculated B-H and N-H bonds are different in lengths also, B-H being 1.20A and N-H being 1.01A. This can be expected due to the electronegativity difference between the boron and nitrogen atoms. The more electronegative nitrogen atom pulls the electron density of the hydrogen atom closer to its nucleus, reducing the N-H bond. As the B atom is more electropositive than the N atom, this happens to a lesser extent and is reflected by a larger B-H bond length. Both of these N-H and B-H lengths match well with those obtained in the analysis of the ammonia borane compounds which shows that the delocaisation of electron density within the borazine system has no effect on these bond lengths.

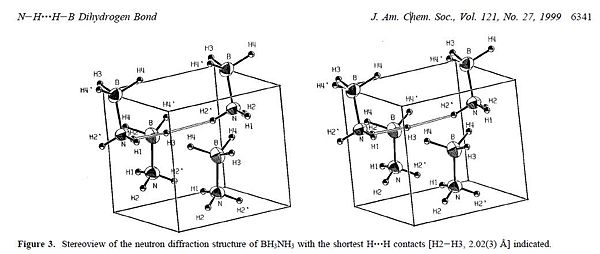

Ethane has a very low melting point but as the ammonia borane derivative has a much higher melting point of around 110 degrees even though these two compounds are isoelectronic. The difference in melting poit between ethane and ammonia boranne is due to stabilsing interactions in the solid state structure of ammonia borane. Ammonia borane has an extremely high polarity compared to ethane which makes it a crystalline molecular solid at room temperature compared to the gas observed for ethane at room temperature. In its solid state and at a temperature at around below 225K, the ammonia borane structure is defined by an orthorhombic crystal structure. At temperatures above 225K, there is significant distortion and the crystal structure is distorted to a tetragonal unit cell[10]. Even though there are two different crystal structures in the solid state at different temperatures, the B-N bond remains the same length with neighbouring AB molecules being linked by dihydrogen interactions[11]. This occurs due to polarity of the system and leads to an increased melting point compared to ethane. From the literature the H-H interaction, the distance between the B-H and N-H bond in two different molecules has been quoted as 2.02A. From the diagram below, taken from the literature it is clear to see this stailising interaction.

I have tried to model the dihydrogen interaction using Gaussview and 4 repeat units arranged in a tetragonal lattice structure as suggested by W. T. Klooster. The molecules were optimised using the same method and basis set as before (DFT B3LYP, 6-31G). The resulting log file returned with the orientations of the molecules changed so that the nitrogen of one molecule and the boron of the other molecule were aligned for a possible H-H interaction to take place. The distance between the B-H and N-H of the opposing molecule was measured at around 2.2 A, which is greater than the literature states but this is a very loose and non accuarte model being used. The DOI for the calculation can be found at: DOI:10042/to-4510

Molecular Orbital Considerations: Benzene vs. Borazine and AB vs. ethane

The molecular oribtals for benzene, borazine, staggered ammonia borane and staggered ethane were computed to show the effect on the MO's of using the isoelectronic N-B system in place of a hydrocarbon system.

Staggered AB:DOI:10042/to-4480 Staggered ethane:DOI:10042/to-4481 Borazine:DOI:10042/to-4467 Benzene:DOI:10042/to-4479

| Orbital | Staggered Ethane | Staggered Ammonia-Borane | ! Borazine | Benzene | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

LUMO+6 |

|||||

Energy of Orbitals |

0.23915 |

0.24965 |

0.16898 |

0.18187

| |

LUMO+5 |

|||||

Energy of Orbitals |

0.18956 |

0.22071 |

0.12493 |

0.16190

| |

LUMO+4 |

|||||

Energy of Orbitals |

0.18956 |

0.22069 |

0.11823 |

0.14517

| |

LUMO+3 |

|||||

Energy of Orbitals |

0.16339 |

0.18574 |

0.11824 |

0.14516

| |

LUMO+2 |

|||||

Energy of Orbitals |

0.16339 |

0.10585 |

0.08952 |

0.09118

| |

LUMO+1 |

|||||

Energy of Orbitals |

0.15473 |

0.10584 |

0.02423 |

0.00268

| |

LUMO |

|||||

Energy of Orbitals |

0.10388 |

0.02816 |

0.02422 |

0.00267

| |

HOMO |

|||||

Energy of Orbitals |

-0.34024 |

-0.26700 |

-0.27590 |

-0.24691

| |

HOMO-1 |

|||||

Energy of Orbitals |

-0.34024 |

-0.26702 |

-0.27591 |

-0.24692

| |

HOMO-2 |

|||||

Energy of Orbitals |

-0.36379 |

0.34862 |

-0.31994 |

-0.33960

| |

HOMO-3 |

|||||

Energy of Orbitals |

-0.43137 |

-0.50381 |

-0.31995 |

-0.33963

| |

HOMO-4 |

|||||

Energy of Orbitals |

-0.43137 |

-0.54783 |

-0.36130 |

-0.35998

| |

HOMO-5 |

|||||

Energy of Orbitals |

-0.61490 |

-0.54783 |

-0.38649 |

-0.41655

| |

HOMO-6 |

|||||

Energy of Orbitals |

-0.74929 |

-0.94744> |

-0.43198 |

-0.41658

|

The computed MO's for all four systems are shown above. Comparing the two non aromatic systems first, it is clear to see that the electronegativity difference between the boron and nitrogen and the nature of the B-N bond has a large impact on the MO's seen for ammonia-borane. For the HOMO's (occupied orbitals), it is clear to see that the orbitals deepest in energy (HOMO-6, HOMO-5, HOMO-4) are skewed towards the nitrogen atom, meaning the nitrogen has a larger weighting coeffcient compared to the boron. The MO's in HOMO-6, HOMO-5 and HOMO-4 will be expected to originate from the nitrogen due to it being more electronegative than the boron and from the NBO analysis, having the greatest contribution towards the percentage orbitals making up the B-N bond. Compaing these MO's to that of ethane, the first main difference observed is that there is no skewed effect. This is expected as the ethane molecule is perfectly symmetric upon rotation and each carbon provides the same and equal orbitals towards bonding, giving a symmetrical MO distribution. Considering the distribution of these MO's, the HOMO-6, HOMO-5 and HOMO-4 all follow a similar pattern to that of its ammonia borane analogue. As we continue to move towardws the frontier orbitals for the ammonia borane, there is a shift in the skewed effect as the MO's begin to dominate on the boron atom instead of the nitrogen atom. This is unexpected as I would still expect these MO's to be based on the more electronegative nitrogen atom. This could be due to the nature of bonding present in the ammonia borane system. Nitrogen donates a lot of its electron density to the electron deficient boron, meaning that the resultant MO's being delocalised onto the boron atom instead of the nitrogen. This is a repeated pattern all the way through the rest of the HOMO series. As with regards to ethane, a symmetrical distribution is still observed which is expected, with the distribution patterns matching those obtained with the ammonia borane analysis. In the comparison of borazine to benzene, it is interesting to consider the HOMO's deep in energy to begin with, especially the HOMO-4. The HOMO-4 for both borazine and benezene shows two electron clouds, one above the plane of the ring and one below the plane of the ring. This enforces the idea that benzene and borazine are both planar molecules and both give delocalisation of their electron density in their conjugated systems. Attack from nucleophiles or electrophiles can occur above or below the plane of the ring as required. The distributions of the other MO's is not similar as it was in the ethane vs. ammonia borane case. For borazine vs. benzene, the HOMO, LUMO and LUMO+2 of each have some kind of ressembelence of each other, which could be down to the aromatic nature of both species.

Frequency Analysis

After the MO analysis, the four molecules were sent for frequency analysis. This frequency analysis helps to show that the molecules have been correctly optimized to their ground state as experimental stretching frequencies can be comapared to literature frequencies. Only important stretches are shown below (i.e. no zero intensity frequencies). Please note also that intensity of stretch is represented by I= 12345 etc. Below the table are the associated IR spectra.

Staggered AB:DOI:10042/to-4524 Staggered ethane:DOI:10042/to-4513 Borazine:DOI:10042/to-4511 Benzene:DOI:10042/to-4512

| Staggered Ethane | Stretching Frequency | Staggered Ammonia-Borane | Stretching Frequency | Borazine | Stretching Frequency | Benzene | Stretching Frequency | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

827, I= 5 |

633, I= 14 |

733, I= 60 |

693, I= 74 |

||||||

1521, I= 7 |

1069, I= 41 |

937, I= 236 |

1066, I= 3 |

||||||

3046, I= 57 |

1196, I= 109 |

1400, I= 11 |

1524, I= 7 |

||||||

3125, I= 70 |

1329, I=114 |

1492, I= 494 |

3175, I= 0 |

||||||

2532, I= 231 |

2641, I= 284 |

3200, I= 47 |

|||||||

3643, I= 40 |

| Staggered Ethane DOI:10042/to-4472 | Staggered AB DOI:10042/to-4469 | Benzene DOI:10042/to-4470 | Borazine DOI:10042/to-4471 |

|---|---|---|---|

The table above shows some selected stretching frequencies for all four molecules in question. Beginning with the aromatic structures, it was clear to see in the analysis that there were a large number of zero intensity stretching frequencies for benzene. This occurs due to the high symmetry of the benzene structure and for a vibration to be active in the infrared spectrum, there must be a change in dipole moment. Due to many highly symmetric vibrations, many of the vibrations were symmetric in nature and thus give 0 intensity stretching frequencies. Borazine however is not as symmetric benzene as this is shown by a multitude of vibrations present in the IR spectrum shown above.

A note on accuarcy

GaussView can predict the energy of a system, bond lengths within the system and bond angles as shown above in this report to many decimal places but we must consider the accuracy to which this program is capable of delivering these figures to us. Generally:

- the energy will have an error of ≈ 10 kJ/mol which can be converted to around 0.00381 Hartrees.

- the dipole moment will be accuate to around 2 decimal places (e.g. 0.01 D)

- the frequencies have a known systematic error of around 10%. Therefore for the larger wavenumbers this can result to a considerable amount of error. The program uses a harmonic approximation for vibrations that are actually anharmonic in nature. Therefore all vibrations will be reported as whole numbers.

- Intensities from the resulting vibrational specta are reported to nearest whole integer which is convention

- bond distances are accurate to ≈ 0.01 Å

- bond angles are accurate to ≈ 0.1°

All calculations were performed using the same method and basis set, unless stated otherwise.

References

- ↑ M. K. Sabra et al, Europhys. Lett. , 1998, 42, 611

- ↑ D. W. Bennett, T. A. Siddiquee, D. T. Haworth, S. E. Kabir and F. Camellia, J. Chem. Cryst., 2004, 34, 353

- ↑ F. A. Cotton, D. J. Darensbourg, S. Klein and B. W. S. Kolthammer, Inorg. Chem., 1982, 21, 294

- ↑ M. Y. Darensbourg and D. J. Darensbourg, J. Chem. Ed., 1970, 47, 33

- ↑ M. Y. Darensbourg and D. J. Darensbourg, J. Chem. Ed., 1970, 47, 33

- ↑ Energy Environ. Sci., 2010DOI: 10.1039/b914338f

- ↑ R. D. Suernam, Chem. Phys. Lett, 1981, 78, 157

- ↑ W.T. Klooster, T.F. Koetzle, P.E.M. Siegbahn, T.B. Richardson and R.H. Crabtree, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121 (1999), pp. 6337–6343

- ↑ R. D. Suernam, Chem. Phys. Lett, 1981, 78, 157

- ↑ M.E. Bowden, G.J. Gainsford and W.T. Robinson, Aust. J. Chem. 60 (2007), pp. 149–153

- ↑ W.T. Klooster, T.F. Koetzle, P.E.M. Siegbahn, T.B. Richardson and R.H. Crabtree, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121 (1999), pp. 6337–6343