Rep:Mod:awc106 module3 part2

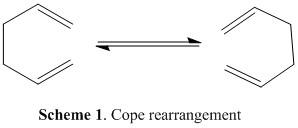

The Diels Alder Cycloaddition

Part (i)

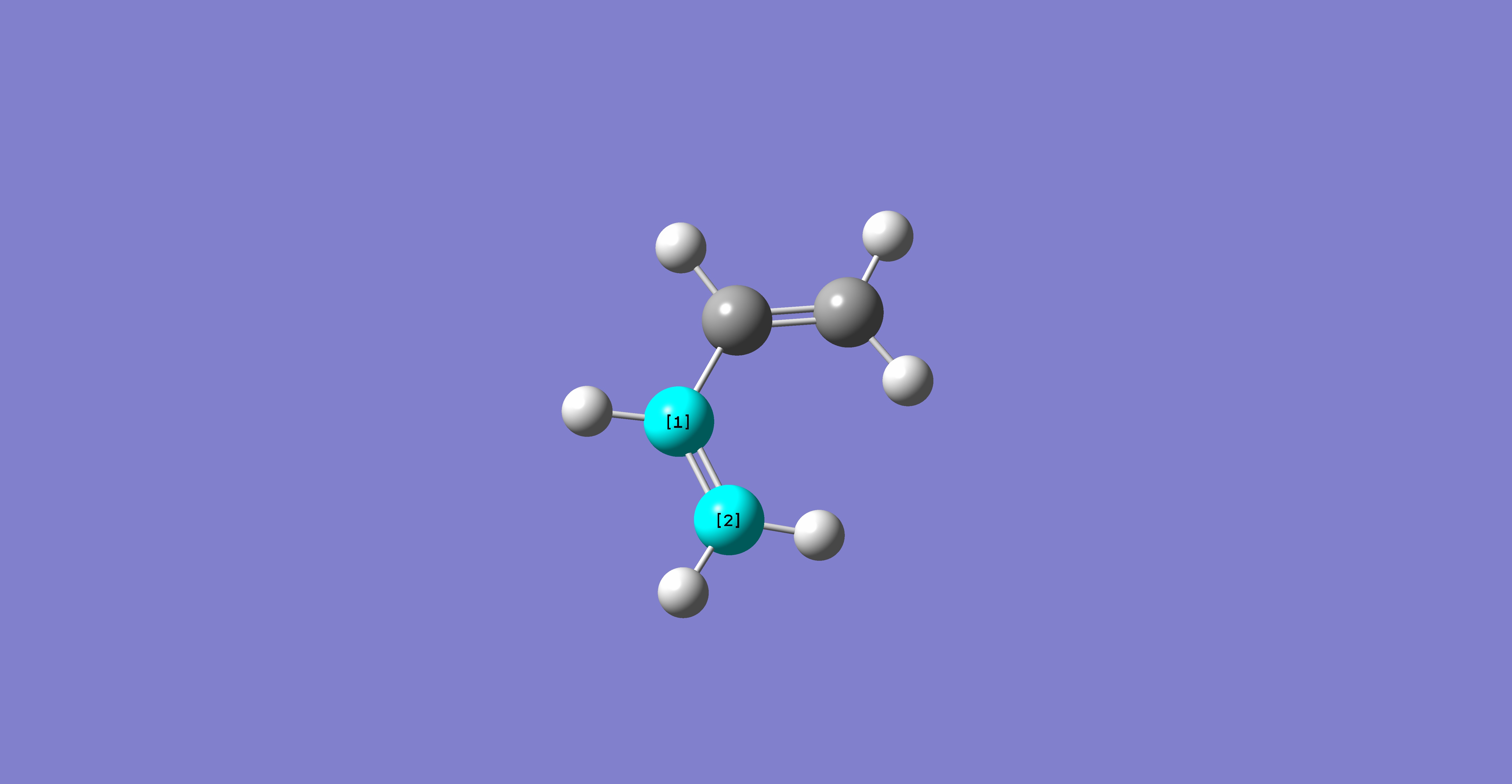

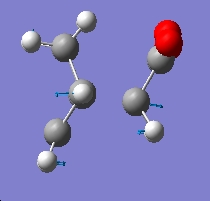

A molecule of cis-butadiene was drawn in Gaussview, and optimised using the AM1 semi-empirical molecular orbital method. After completion, the molecular orbitals were available:

Table 15: Molecular Orbitals of Cis-Butadiene | |||

| Molecular Orbital | Image | Symmetry with

Respect to Plane | |

| HOMO |

|

Antisymmetric | |

| LUMO |

|

Symmetric | |

https://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/8/87/CIS_BUTADIENE_OPT.LOG

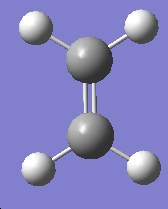

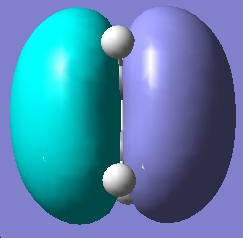

The same was done for ethylene

Table 16: Molecular Orbitals of Ethylene | |||

| Molecular Orbital | Image | Symmetry with

Respect to Plane | |

| HOMO |

|

Symmetric | |

| LUMO |

|

Antisymmetric | |

https://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/6/62/Ethylene_mo.log

Part (ii)

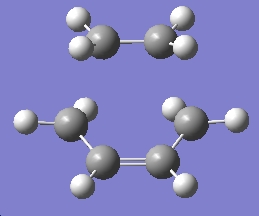

Using the optimised forms of the butadiene and ethylene fragement, the two were pasted onto the same molgroup file, and were positioned in a guess structure, setting the bond forming/breaking distance to 2.2Ă. The molecule was then optimised to a TS Berny, rather than a minimum, calculating the force constants once, and "opt=noeigen" in the keywords, and finally using the HF/3-21G method and basis set. The following results were obtained:

Table 17: Initial Optimisation of Transition State | ||||

| Conformer | Structure | Point Group | Energy/Hartrees

HF/3-21G |

Imaginary Frequency/cm-1 |

| Chair Transition State |

|

Cs | -231.60321 | -818.38 |

https://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/6/64/Ts_guess.log

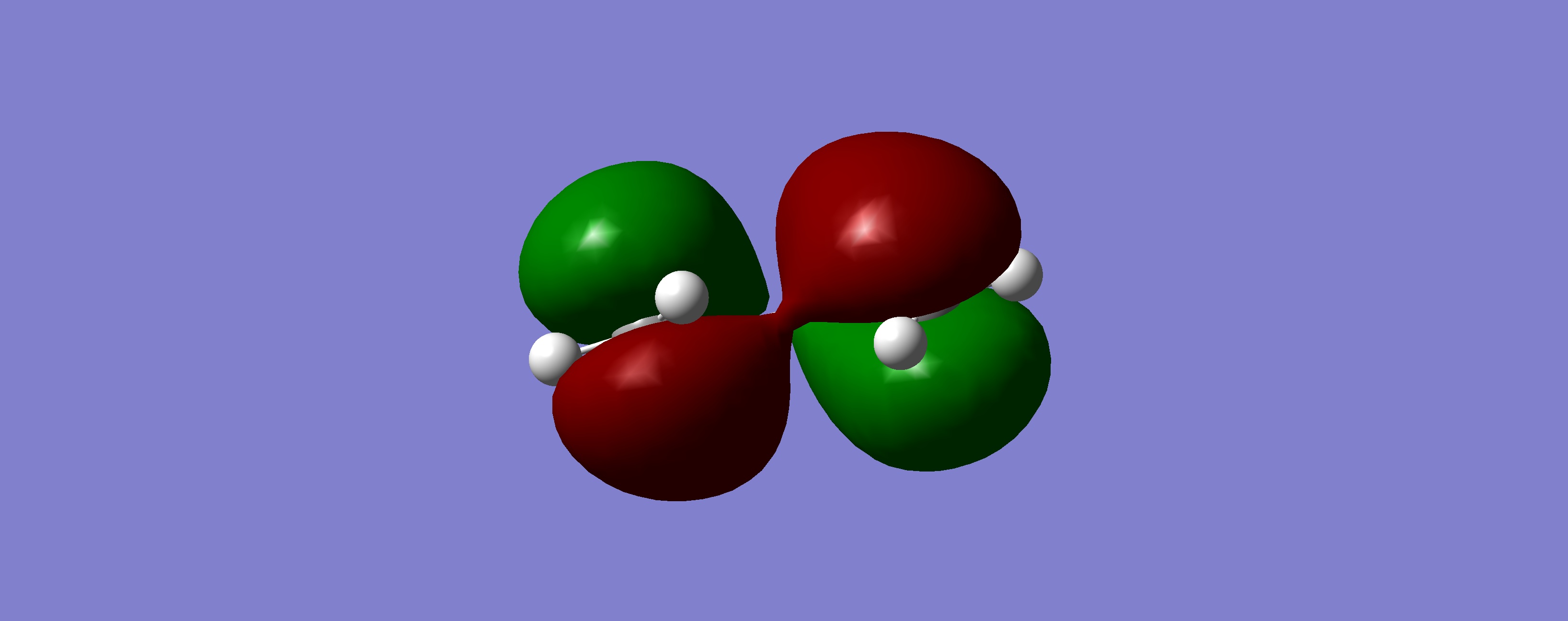

The imaginary frequency corresponded to the following motion:

Which as can be seen, does correspond to the formation and breaking of bonds in the transition structure, and that the formation of the two bonds synchronous, i.e. both bonds form at the same time. We can compare this imaginary frequency to the lowest positive frequency, which has a value of 166.56cm-1, and this frequency corresponds to the following motion:

Here we see that the lowest frequency correspnds to a rocking of the two parts of the transition structure, compared with the imaginary frequency which is a bending motion.

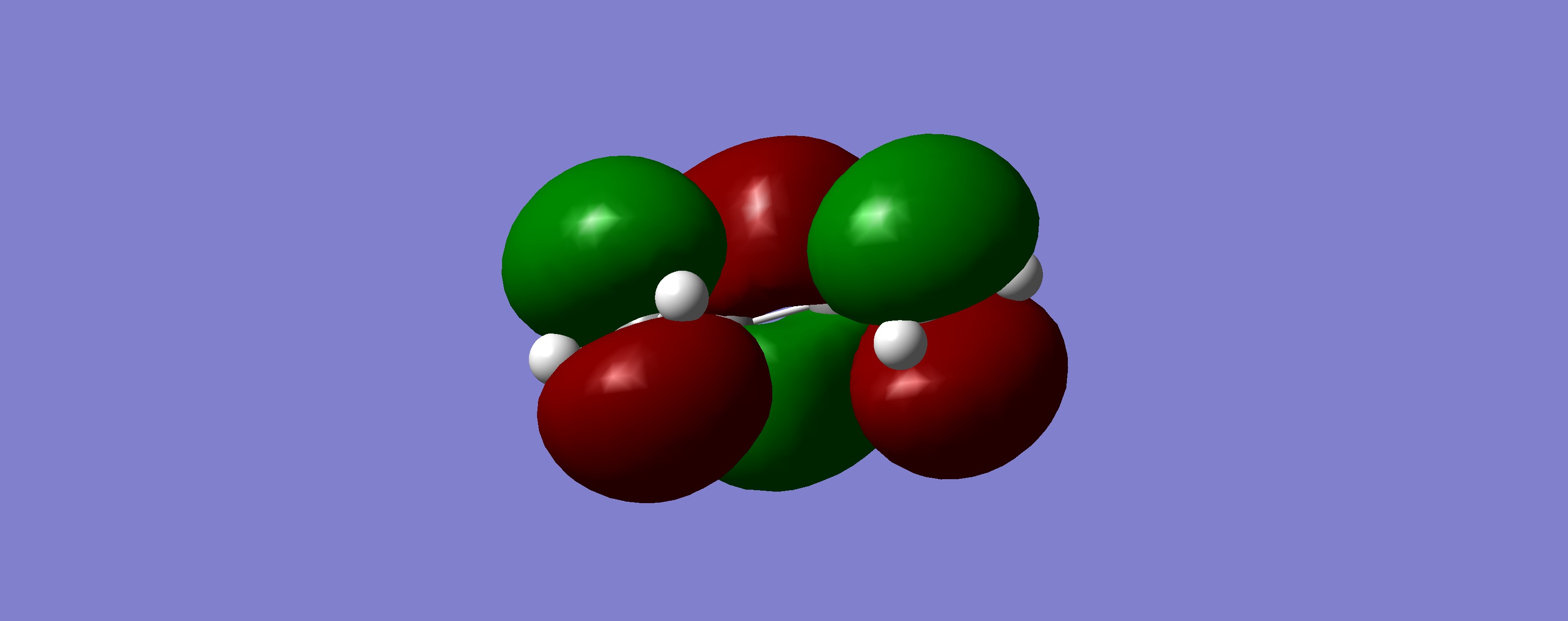

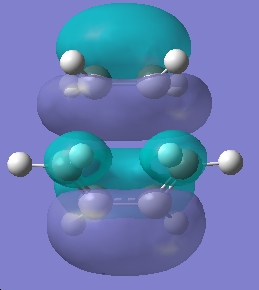

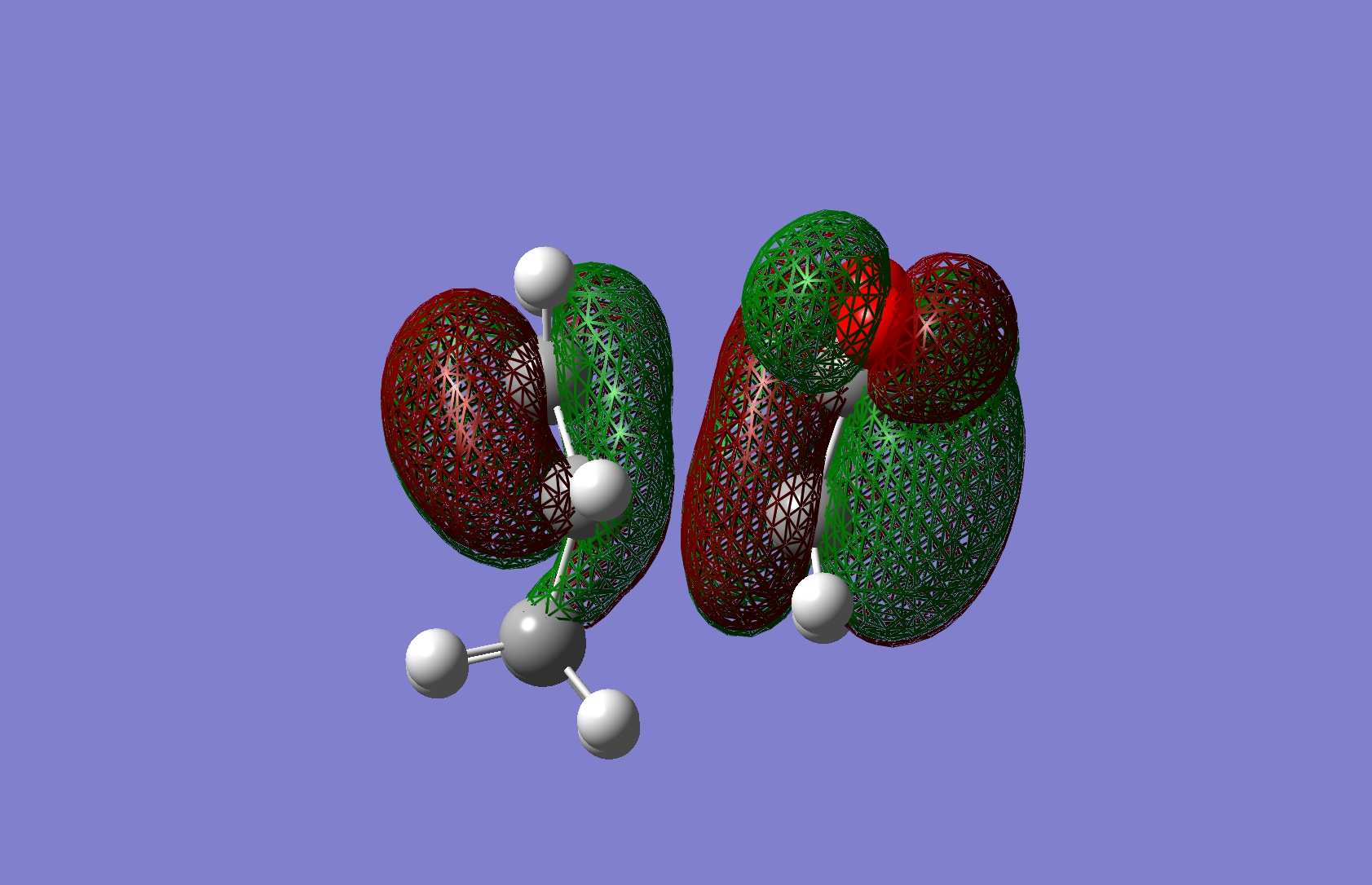

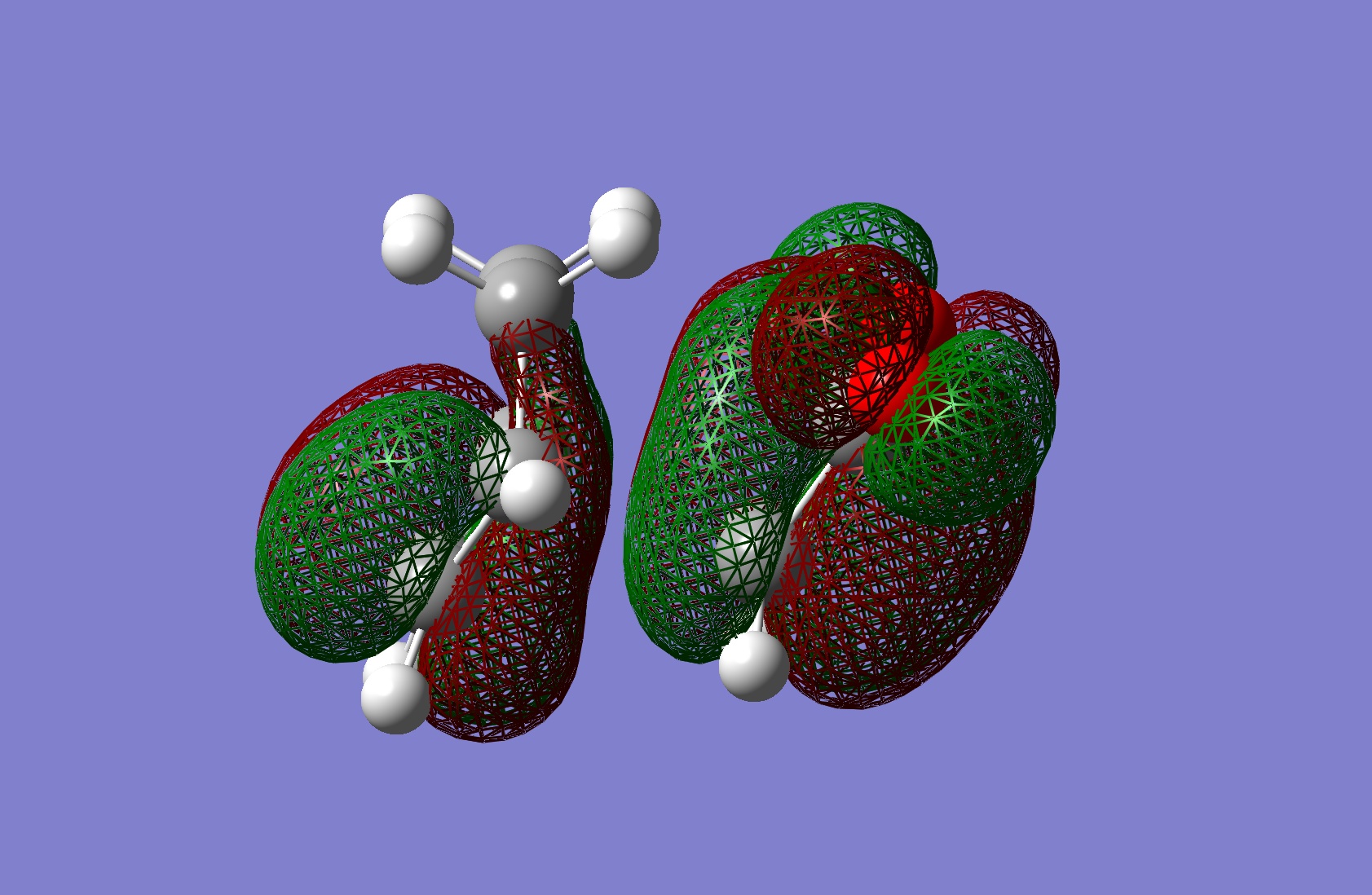

Next another optimisation was run, this time using the semi-empircal/AM1 method, so as to calculate the molecular orbitals of the transition state.

Table 18: Molecular Orbitals of Transition State | |||

| Molecular Orbital | Image | Symmetry with

Respect to Plane | |

| HOMO |

|

Symmetric | |

| LUMO |

|

Symmetric | |

https://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/b/b6/TS_MO.LOG

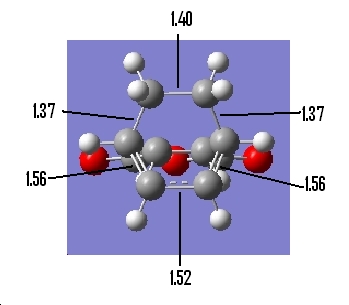

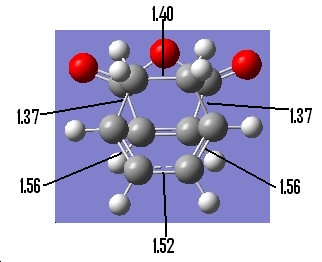

Using the investigate tools in Gaussview, the follwing information about the transition state was available:

Table 19: Geometry of Transition State | |||

| Bond Lengths of Partly

Formed σ C-C bonds/Ǎ |

Average sp3

Bond Length/Ǎ |

Average sp2

Bond Length/Ǎ |

van der Waals radius

of the C atom/Ǎ[1] |

| 2.21 | 1.39 | 1.37 | 1.70 |

What we can see by examining the frontier orbitals of the reactants, is that it is in fact the HOMO of ethylene and the LUMO of butadiene which react to from the transition state and then the product. We notice that both the molecular orbitals have the same symetry, both are symmetric with respect to the plane. We can also note that the reaction is allowed due to the fact that it is a six electron process, and therefore conforms to the 4n+2 rule under thermal conditions. The two molecular orbitals therefore react via a suprafacial conformation.

- ↑ A. Bondi; J. Phys. Chem., 1964, 68 (3), pp 441–451. DOI:10.1021/j100785a001

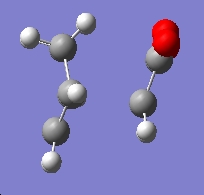

Part (iii)

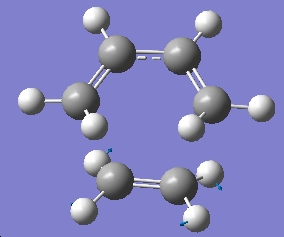

The aim of this part of the report is to Study the regioselectivity of the Diels Alder Reaction, by computing the exo and endo confomrers of the transition state of the reaction between cyclohexa-1,3-diene with maleic anhydride. The reaction is kinetically controlled, the exo transition state should therfore be higher in energy, due to greater steric congestion.

Firstly the endo transition state was modelled by drawing out the two fragments, and positioning them in a guess structure, setting the bond forming/breaking distance to 2.2Ă. The molecule was then optimised to a TS Berny, rather than a minimum, calculating the force constants once, and "opt=noeigen" in the keywords, and finally using the HF/3-21G method and basis set.

Table 20: Optimisation of Endo Transition State | ||||

| Conformer | Structure | Point Group | Energy/Hartrees

HF/3-21G |

Imaginary Frequency/cm-1 |

| Endo Transition State |

|

Cs | -606.35754 | -645.29 |

Upon inspection of the results, only one negative frequency was present, indicating that the optimised structure is indeed a transition state. A visulaisation of its motion is represented in the picture below:

This visualisation shows us that the negative frequency corresponds to the synchronous formation of the two σ bonds, and also the elongating and breaking of the π bonds. This result confirms to us that the reaction is indeed a pericylcic cycloaddition.

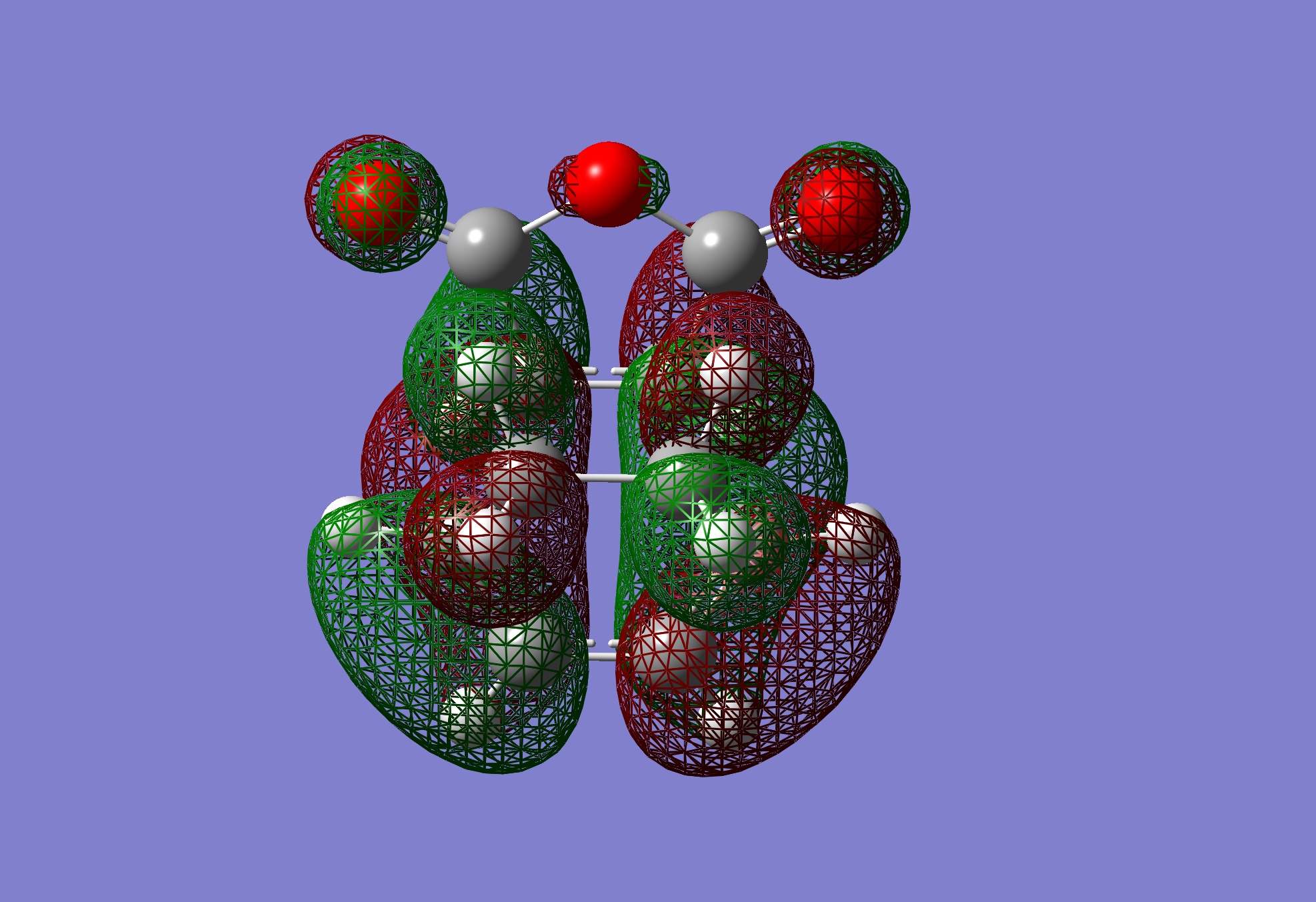

Using the checkpoint file from the optimisation, and editing the MOs, it was possible to view the HOMO and LUMO of the transition state.

Table 21: Molecular Orbitals of Endo Transition States | |||

| Molecular Orbital | Image | Symmetry with

Respect to Plane | |

| HOMO |

|

Antisymmetric | |

| LUMO |

|

Antiymmetric | |

Again using the inspection tools in Gaussview the follwing information was available:

Table 22: Geometry of Endo Transition State | ||

| Bond Lengths of Partly

Formed σ C-C bonds/Ǎ |

C-C Through Space Distance Between

the C=O-CO-C=O- Fragment and -CH2=CH2-/Ǎ |

Other C-C DIstances/Ǎ |

| 2.24 | 2.84 |

|

https://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/5/52/ENDO_TS.LOG

The same was done for the exo transition state:

Table 23: Optimisation of Exo Transition State | ||||

| Conformer | Structure | Point Group | Energy/Hartrees

HF/3-21G |

Imaginary Frequency/cm-1 |

| Exo Transition State |

|

Cs | -605.60359 | -647.54 |

https://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/4/4f/Exo_ts_final.log

Again we have one negative frequency which corresponds to the fact that we have optimised a transition state. A visulaisation of the frequency can be seen below:

In comparing the endo and exo forms, we see that both have very similar negative frequencies, and indeed that both correspond to the synchronous formation of the two σ bonds, and also the elongating and breaking of the π bonds, and again that the reaction is indeed a pericylcic cycloaddition.

Table 24: Molecular Orbitals of Exo Transition State | |||

| Molecular Orbital | Image | Symmetry with

Respect to Plane | |

| HOMO |

|

Antisymmetric | |

| LUMO |

|

Antisymmetric | |

Table 25: Geometry of Exo Transition State | ||

| Bond Lengths of Partly

Formed σ C-C bonds/Ǎ |

C-C Through Space Distance Between

the C=O-CO-C=O- Fragment and -CH2-CH2-/Ǎ |

Other C-C DIstances/Ǎ |

| 2.26 | 2.92 |

|

Now we are able to compare the endo and exo transition states relative geometries. What we notice is that in the exo transition state, the forming bonds are longer than in the endo conformation. As the new bonds are forming, we can see that there will be a much greater steric repulsion between the groups on the exo form, compared with the endo form, hence why the endo is kinetically more stable.

There is also a theory that there is a secondary oribtal overlap between the π bonds in the endo transition state, which corresponds to the the two groups being closer together, and a lowering of the overall energy of the transition state. We can examin the calculated molecular orbitals to investigate this. Secondary orbital interactions are not responsible for formal bonds, but attractive interactions between two sets of molecular orbitals.