Rep:Mod:aw

Transition States and Reactivity

The Cope Rearrangement Tutorial

Having optimised all the conformers using a 3-21G basis set, the anti2 conformer was then optimised using the higher basis set of B3LYP/6-31G*, giving the following as its result. As can be seen the geometries of the 2 are similar and show no visible differences. The point group of both molecules is also the same as to be expected, as the symmetry of the molecule should not change during further optimisation.

Looking at the anti2 conformer we can see its vibrations and produce and IR spectrum by running a frequency analysis. This will help ensure the molecule completely optimised, showing that it is indeed a minimum which has been acheived, and allow us to see if all frequencies shown are 'real', (not negative). As can be seen from the IR spectrum there are no negative frequencies showing the optimisation was complete and all vibrations are real.

By looking at the conformer energies calculated, the energy of the molecule on the bare potential surface, it is possible to compare this to experimental data, showing how useful this method is and to check calculations are in the correct area. The values we are going to be comparing are; the sum of the electronic and zero point energies (this is the potential energy of the molecule at 0K), the sum of the electronic and thermal energies (the energy at standard conditions, which will include translational, rotational and vibrational energy modes), the sum of the electronic and thermal enthalpies (basically a correction, useful for dissociation reactions), and finally the sum of electronic and thermal free energies (a measure of entropic contribution to the Gibbs free energy). The data collected is shown below,

Sum of electronic and zero-point Energies= -234.416252 Sum of electronic and thermal Energies= -234.408952 Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies= -234.408008 Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies= -234.447897

Optimising the chair and boat transition state geometries

Both structures contain 2 allyl fragments which are approximately 2.2A apart. One has a symmetry of C2v compared to the others C2h.

Chair

There are two ways of optimising the transition structure, the first relies on a good guess structure, assuming the seperate fragments are the correct distance from each other. This method computes the force constant matrix in the first step of the optimisation and updating this as the optimisation is run. The second method involves freezing the coordinates of the fragments, minimizing the rest of the molecule and then unfreezing and computing the transition state. This can be a quicker method. An allyl fragment was drawn and optimised using the HF/3-21G basis set, this was copied into a new window with another of the same fragment and placed with the terminal carbons' being roughly 2.2A apart, this served as our guess structure. This was then optimised using calculations for the tranisition state, instead of optimising to a minimum. This method did run successfully as can be seen by the molecule showing a single imaginary frequency at -817.94, corresponding to the vibration shown. For the second methos we started with the guess structure as before, and this time froze the terminal carbon bond distances via the reduntant coordinate tool in Gaussview, this ensured they stayed near the expected 2.2A. A minimum optimisation was then run on the molecule at the required distances. Once this was compelted the bonds were then unfrozen and the derivative was then found, a transition state optimisation could then be run, on these bonds. By comparing the two structures found for the transition structure it can be seen that both are visibly similar, and have similar distances between the terminal carbons. Optimising the tranistion state straight from the guess structure gives a bond distance of 2.020A, whereas finding the structure via freezing bonds gives a distance of 2.019A, showing that both have optimised to the same structure.

Boat

To optimise the boat structure the QST2 method was used, this involved forming both the reactants and the products and allowing the calculation to interpolate the transition structure from these. This also meant that both reactant and product needed to be numbered correctly for the calculation to be successful, this is a very time consuming process and also introduces multiple routes for error. Firstly the anti2 conformer of 1,5-hexadiene was taken and copied twice into a new window in Gaussview, this was taken as the reactant and product. Haveing ensured all atoms were labelled correctly, the first optimisation to a transition state was carried out. This however did not give the expected structure, most probably due to the large distance the two terminal carbon would have to cover in order to bond. Therefore the geometry of the molecule was changed for the reactant and product by changin the angle of the main backbone of the molecule to 0°, turning it to a gauche conformer as opposed to an app one. After this change, the optimisation was run again giving the expected structure.

Having optimised the transition structures of the boat and chair conformers we can deduce their corresponding conformers by using IRC. This is Intermediate Reaction Coordinates, and works by taking small geometry steps in the direction where the gradient or slope of the energy surface is steepest, closest to the minimum.

The graphs showing the minimum and pathways taken can also be seen here.

As can be seen after the IRC the chair transition structure does from a Gauche conformer, notably the gauche 2 conformer, to a further gauche conformer (as the reaction is symmetric in its forward and reverse direction.

Activation Energies for reactions

Chair frequency analysis at lower basis set (HF/3-21G)

Sum of electronic and zero-point Energies= -231.466700 Sum of electronic and thermal Energies= -231.461340 Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies= -231.460396 Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies= -231.495206

Boat frequency analysis lower basis set (HF/3-21G)

Sum of electronic and zero-point Energies= -231.450932 Sum of electronic and thermal Energies= -231.445302 Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies= -231.444358 Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies= -231.479778

The transition state structures were optimised further using a higher basis set of 6-31G.

Chair

| File Name | CHAIROPTHIGH |

| Calculation Type | FREQ |

| Calculation Method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | 6-31G |

| E(RB3LYP) | -234.50546640 a.u. |

| RMS Gradient Norm | 0.00004073 a.u. |

| Dipole Moment | 0.0000 Debye |

| Point Group | C1 |

| Job cpu time | 0 days 0 hours 2 minutes 39.0 seconds |

After enabling point groups the symmetry was C2h, as before.

Sum of electronic and zero-point Energies= -234.362690 Sum of electronic and thermal Energies= -234.356773 Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies= -234.355829 Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies= -234.391622

Boat

| File Name | boat_opt_high_freq |

| Calculation Type | FREQ |

| Calculation Method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | 6-31G |

| E(RB3LYP) | -234.49291447 a.u. |

| RMS Gradient Norm | 0.00003073 a.u. |

| Dipole Moment | 0.0710 Debye |

| Point Group | C1 |

| Job cpu time | 0 days 0 hours 2 minutes 14.9 seconds |

After point groups were enabled the symmetry was found to be C2v.

Sum of electronic and zero-point Energies= -234.351355 Sum of electronic and thermal Energies= -234.345052 Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies= -234.344107 Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies= -234.380776

Activation Energies of the different conformers

| Activation energies chair | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HF3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G ! | |||

| Eelec+ZPE | Eelec+Therm | Eelec+ZPE | Eelec+Therm | |

| Anti2 au | -231.539539 | -231.532566 | -234.416252 | -234.408952 |

| Chair TS au | -231.466700 | -231.461340 | -234.362690 | -234.356773 |

| Eact au | 0.072839 | 0.071226 | 0.053562 | 0.052179 |

| Eact kcal/mol | 45.70669 | 44.69452 | 33.61031 | 32.74248 |

| Activation energies boat | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HF3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G ! | |||

| Eelec+ZPE | Eelec+Therm | Eelec+ZPE | Eelec+Therm | |

| Anti2 au | -231.539539 | -231.532566 | -234.416252 | -234.408952 |

| Boat TS au | -231.450932 | -231.445302 | -234.351355 | -234.354052 |

| Eact au | 0.088607 | 0.087264 | 0.064897 | 0.0549 |

| Eact kcal/mol | 55.60116 | 54.75842 | 40.72306 | 34.44991 |

From the tables we are able to see that the chair conformer has a lower activation energy than the boat conformer, due to less steric overlap felt in the molecule and a stronger orbital overlap. Against the experimental values given for activation energies, 33.5±0.5 kcal/mol and 44.7±2.0 kcal/mol for chair and boat respectively, this shows a relatively good match for the chair structure. Both show greater correlation to the value at a higher basis set as would be expected due to the larger accuracy this can give the structure.

The Diels Alder Cycloaddition

The Diels Alder cycloaddition is a well known reaction, and we will look at the transition structures that it can go through. The reaction is a pericyclic reaction, in which the π orbitals of both a diene and dieneophile are used to form a new σ bond, the success of the reaction depends mainly on the number of π electrons available. Generally the HOMO of one will react with the LUMO of the other, this can only happen if they both have the same symmetry properties as this will give a large orbital overlap, thus making the reaction feasible. Dienophile substituents can interact with the new double bond being formed thus helping to stabilise the regiochemistry. In this wiki the nature of the transition states will be examined both for prototypical reactions, those in which substituents are present and those which may contain secondary orbital effects.

Cis butadiene + ethylene cycloaddition reaction

Butadiene

The cis isomer of butadiene was created in Gaussview and optimised using the AM1 semi-empirical method. (For reference all calculations will be carried out in this method)

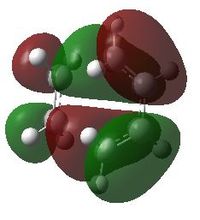

Looking at the MO's of this molecule we can tell the symmetry properties that it contains, and the total symmetry of the molecule, which was found to be C2v when symmetrised. When looking at the MO's bear in mind the plane is that which passes through the C2-C3 bond of the carbon atoms in butadiene.

HOMO of the cis-butadiene

LUMO of the cis-butadiene

Transition state

The transition state is known to occur through a slight envelope shape, with overlap of orbitals between the ethylene π orbitals and the π system of butadiene similar to that seen in the bicyclo(2,2,2)octane molecule. As a result this molecule was taken as the basis of the transition state, with a CH2-CH2 fragment taken off and relevant bonds broken and doubled. The methods above can each be used to locate the transition state, but the method used here will be attempting to locate it straight from the guess structure. the initial distance guessed between the diene and dienophile was 2.2A. This gave a successful transition state as shown below. Certain keywords were used to ensure the transition state was found, these were ensuring force constants were only calculated once, and that there was no eigen test involved.

The bond lengths for the partially formed C-C bonds in the transition state are 2.119A. Typical bond lengths for a C-C bond are shown here --> sp3-sp3 - 1.53A, sp2-sp2 - 1.46A. The Van der Walls radii of a C atom is 1.70A. The partially formed C-C bonds are less than twice the VdW radii showing that at these distances both the orbitals are involved and are able to interact, showing bonding orbital character. However the bond distance is distinctly less than that of a normal fully made bond further indicating that the bond is not yet fully formed and therefore longer than it will be when complete.

As can be seen in the summary results table there was 1 imaginary frequency found, as to be expected proving a transition state has been reached, relating to the movement of the transition state in forming the 1,5-cyclohexene.

| File Name | TS_FREEZE41 |

| Calculation Type | FREQ |

| Calculation Method | RAM1 |

| Basis Set | ZDO |

| E(RAM1) | 0.11165464 a.u. |

| RMS Gradient Norm | 0.00001001 a.u. |

| Imaginary Freq | 1 |

| Dipole Moment | 0.5607 Debye |

| Point Group | C1 |

| Job cpu time | 9.0 seconds |

This imaginary frequency seen here

Frequencies -- -956.4387

in the results is shown as a vibration below. This imaginary frequency corresponds to the reaction pathway at the transition structure, which shows two new σ bonds being former synchronously. The individual motion of the molecules can be seen by looking at the lowest vibration.

As seen by the individual motion there is no major interaction between the two molecules leading to a larger frequency difference between real and imaginary frequencies (147.21 and -976.43 respectively).

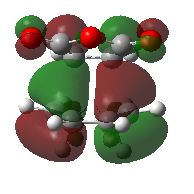

The MO's of the transition state can be seen here,

LUMO -

As can be seen the LUMO of the transition state is symmetric therefore giving an antisymmetric HOMO molecular orbitals. For this antisymmetric product to occur the molecular orbitals involved must include the HOMO of the butadiene molecule (antisymmetric) and therefore the LUMO of ethene. Both these MOs will contain 1 nodal plane, through the C2-C3 bond of butadiene. The LUMO of the transition state therefore compromises of the HOMO of ethene and the LUMO of cis-butadiene, as this orbital is symmetric with respect to the plane (through the C2-C3 bond of butadiene) and the transition state will therefore include two nodes (between C1-C2 and C3-C4 of butadiene). The antisymmetric HOMO of the transition state is to be expected as the final product of the diles-alder reaction is itself antisymmetric. The expected MOs forming this state are allowed to react due to their differing symmetry properties therefore conserving orbital symmetry. The reaction also involves the forming of 2 new σ bonds.

Diels Alder Reaction Regioselectivity

If the dienophile in the diels-alder reaction has substituents which contain pi orbitals it may interact with the double bond formed in the product and affect the regio-chemistry. In order to study the regioselectivity of this reaction we will look at the reaction of cyclohexa-1,3-diene and maleic anyhdride in which two products are formed, endo and exo. The reaction primarily gives the endo product which is supposed to be formed through kinetic control. The two transition structures can be seen below, in picture form, these were found using the freeze coordinate methods with the coordinates frozen at roughly 2.2A, a minimum located, the bonds derived and a transition structure found.

The transition structures each showed one imaginary frequency, as to be expected, showing the reaction pathway taken. These vibrations are shown on the tabs below.

The imaginary frequencies corresponding to the pathway for exo and endo are -812.71 and -806.97 respectively.

The MO's of the seperate pathways can also be looked at. The HOMO and LUMO of the exo regio-isomer can be seen below.

Both the HOMO and LUMO show antisymmetric properties, the antisymmetric nature, containing 1 nodal plane, of the HOMO tells us that it is formed from the HOMO of the diene and the LUMO of the dienophile.

The HOMO and LUMO of the endo regio-isomer can be seen below

Both HOMO AND LUMO have antisymmetric properties similar to that of the exo regio-isomer. The antisymmetric nature and 1 nodal plane shows that it is formed of the HOMO of the diene and LUMO of the dienophile.

The preferred regio-structure will depend on multiple factors, including steric repulsion and strain caused by steric hindrance, and their differences in the two structures. These will also be affected by secondary orbital interactions which may be felt in these systems due to the pi system of the double bond in 1,5-cyclohexene and the pi system in the maleic anhydride which will be felt in the endo isomer. This is due to the overlap of the oxygen fragment of maleic anhydride and the double bond, and as such will not be felt in the exo isomer due to its geometry. The strain in the exo isomer will most likely be caused by the steric clashed between the oxygen atoms and the carbons contained in the CH2-CH2 bridge, not present in the endo form again for geometrical reasons. Steric clashes can also be felt in the isomers due to the angle the maleic anhydride comes in to react at. These steric clashes will mainly be felt for only one isomer due to its direction of attack. In the endo form the maleic anyhdride approaches from the side of the double bond, and therefore has no steric affects, whereas as the exo form approaches from the end with the carbon bridge there are possible interactions with the C=O bond and the bridge therefore allowing for some steric clash. This helps explain why the endo form is most notably the main product. As seen the approach of the endo form is slightly easier due to less steric clashes, this can be seen in the partly formed C-C bonds in the transition states, showing different distances, endo being a shorter bond of 2.16A compared to exo's 2.17A.

From the relative energies of the two isomers it can be seen that the endo form has a lower energy compared to the exo form. As a result it is the kinteically favoured product requiring less energy to reach the transition structure and therefore requiring less energy in forming the product. One of the reasons for this can be seen by looking at the secondary orbital overlap. Both HOMO orbitals which have been shown above show 1 nodal plane and antisymmetric properties. However there can be other nodes sen in the molecule, these can be seen by looking specifically at the HOMO of the -(C=O)-O-(C=O)- fragment and its interactions with the rest of the system. Looking specifically at the endo system for now, it can be seen that at the angle which the maleic anhydride reacts at there can be another orbital interaction between one of the carbons double bonded to an oxygen and the opposite end of one of the double bonds interacting with the double bond on the maleic anhydride[1]. This can be easier seen in a diagram, as shown here. There is also a diagram involving the exo isomer and from this it can easily be seen how the secondary orbital overlap effect plays no part when considering this isomer[2]. This extra orbital bonding helps stabilise the molecule further reducing its energy and making it more kinetically favourable.

Errors in the programming

Some computational evidence says that semi-empirical methods which favor the overlap described above favor a biradicloid transition state, whereas methods which ignore the overlap effect favor a syncrhonous transition state. [3] . The calcualtions also neglect errors involved with tunneling through the molecule and more generally deviations form transition state theory. The method also ignores solvent effects which may help favour the exo formation.

References

- ↑ I. Fleming, Frontier Molecular Orbitals and Organic Chemical Reactions, 1976, Wiley

- ↑ R. Hoffmann, R.B. Woodward, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1965, 87, 4388-4389

- ↑ J.A. Pople, J. Am. Chem. Sac., 97, 5306 (1975); W. J. Hehre, ibid., 97, 5308 (1975); W. N. Lipscomb, Science, 190, 591 (1975); M. J. S. Dewar, J. Am. Chem. SOC., 97, 6591 (1975); Science, 190, 591 (1975)