Rep:Mod:atbxz79363

The Diels Alder Cycloaddition between Butadiene and Ethene

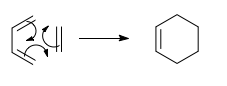

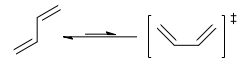

The Diels Alder reaction is a π4s + π2s cycloaddition between a diene and a dienophile, to form two new σ bonds from the termini of a conjugated π system.

We shall initially investigate the prototype reaction, that between butadiene and ethene. Using the symmetry properties of the Frontier orbitals of the reactants, we will show that this reaction is allowed, and make a prediction as to the geometry and orbitals of the transition state. Then the prediction will be tested by optimising the transition state and comparing the prediction to results. We will also investigate the energy profile of the reaction, by optimising the reactants and products, and comparing their energies, and also comparing to the energy of the transition state.

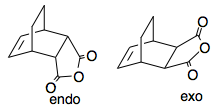

Then, we look at the Diels Alder cycloadditon between Maleic anhydride acting as the dienophile and 1,3-Cyclohexadiene, exploring the regioselectivity of addition. Depending upon the orietation of the reactants, we can imagine two diasteroisomeric products, endo- and exo-product. We shall again use the principles of orbital symmetry conservation to explain which product we get, and demonstrate this by looking again at the reaction profile.

Orbital Symmetry in the Diels Alder Reaction

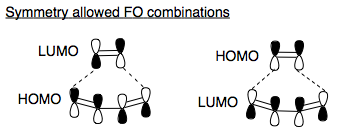

Pericyclic reactions are controlled by the symmetry of the frontier orbitals of the fragments reacting. We are going to predict whether this reaction is allowed, by using the Fukui method of reaction prediction (FO approach), which says that a filled HOMO mixes with an empty LUMO, stabilising the system, and forming a new sigma bond, but only if the orbitals can form symmetry allowed combinations.[1] Hence, we shall visualise the FOs of the fragments, and determine which mixing is allowed.

So what are the frontier orbitals? Ethene is our archetypal π system, featuring a π homo and π* LUMO. The HOMO is symmetric with respect to a plane bisecting the molecule, and the LUMO is antisymmetric with respect to that same plane.

The HOMO of the cis-butadiene is also a π system, with equal coefficients on both π orbitals, since the two termini are equivalent. This orbital is antisymmetric with respect to a plane of symmetry bisecting the molecule The LUMO also is the π* orbitals of the two double bonds, and is symmetric with respect to this plane.

|

Frontier Orbitals of Ethene and cis-Butadiene |

|||||

|

Orbital: |

Ethene HOMO |

Ethene LUMO |

cis-Butadiene HOMO |

cis-Butadiene LUMO |

|

|

Plot: |

|||||

|

Symmetry w.r.t Plane: |

S |

A |

A |

S |

|

Orbitals of like symmetry can mix and form new σ bonds, if one is empty and one is filled. Because of the symmetry constraint, the geometry of approach is key, since only if the two orbitals approach each other so as to maintain their same-symmetry will we get reaction. The ethene LUMO and butadiene HOMO and both antisymmetric with respect to a plane of symmetry. Similarly, the butadiene LUMO and ethene HOMO and both symmetric with respect to the plane. Hence, given that these two reactants approach each other whilst maintaining that plane, the reaction is allowed, as the HOMO or one fragment can mix with the LUMO of the other, and form the new bonds.

We can now make a prediction as to the geometry of the transition state. As we have said, it has to keep the symmetry of the orbitals with respect to the plane bisecting the molecule. To form two new sigma bonds from π bonds, we have to rehybridise sp2 to sp3, and we require the π bonds of like phase in the transition state to approach end on. Hence, we can form two guesses as to the orbital picture in the transition state, from our symmetry allowed combination of FOs , above. We couldn't make a guess as to which case we have without calculation, because these are both fairly 'electronically neutral' alkenes, i.e no electron pushing or withdrawing substituents to shift the energy levels up or down.

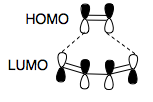

Below, we discuss the method we used to optimise this transition state. But for the moment, let us jump ahead, and use the result of this transition state optimisation, to visualise the orbitals, and compare to our prediction. The HOMO of the transition state is symmetric with respect to the plane bisecting the molecule. Also, the molecular geometry respects this symmetry - the reaction would be disallowed in other geometries. Because it is S, we can show that the LUMO of the butadiene and the HOMO of the ethene mix. These must be the two FOs closest in energy, hence when they interact, they form the most stable bonding orbital. We see that the coefficients of the mixing orbitals have changed from those in the reactants. This is because the new bonds are part formed, so we see the cyclohexene π bond forming, and the ethene π bond and cis-butadiene π bonds breaking, with increasing electron density in between the two molecules, where the sigma bonds are forming.

A typical value for an sp3C-sp3C bond is 1.54Å. Likewise, that for sp2C-sp2C is 1.32Å. IF we measure the lengths of bonds in the transition state, we find that the σ bond of the butadiene is now 1.41Å, and the π bonds of the butadiene are 1.38Å. These are in between the typical values, showing that the bonds are changing their character, as the orbitals mix. Likewise, the ethene bond distance is increased to 1.39Å in the transition state.

|

Diels Alder Transition State HOMO |

|

|

Computed Picture: |

Guess: |

Comparing to our guess, we see that although the shapes of orbitals have changed, we can still determine the MO's which come together to react, which we correctly predicted based upon consideration of symmetry allowed FO combinations.

Optimising reactants and product

Compared to the Cope rearrangement, the Diels Alder reaction is Bi-molecular and hence involves an unsymmetrical energy profile. We will, as before, first optimise the reactants and products, exploring their conformational preferences. The absolute energies of species discussed is presented in tables below. Energy changes will be discussed.

Reactants

Ethene will only have one stable minimum, because necessarily it is planar. Minimising to DFT/B3LYP/6-31Gd level of theory, produced such a planar geometry with a C-C distance of 1.32Å.

Butadiene is not so simple. Although the termini are fixed, by virtue of the double bonds, we can get rotation about the central C-C bond, resulting in different conformations, of which we would expect some to be minima and some transition states between them. To study the potential surface associated with rotation about that central dihedral, a SCAN calculation was carried out. Initially, the structure of cis-butadiene was optimised, initially HF 3-21G, then to DFT B3LYP 6-31G*. With the resulting geometry, using the redundant coordinate tool, the dihedral angle was defined, and set to scan 72 steps, in 5o intervals, i.e a whole rotation from cis- to cis-butadiene. A relaxed-scan was then carried out to HF/3-21G theory. The plot of the energy profile, and maxima and minima structures for this bond rotation is shown below.

Apart from the anomalous points, which must be due to poor optimisations, we obtain a symmetrical cuvre about the all trans (or about the all cis) conformer, i.e rotation in either direction is equivalent, as expected. The mimima and maxima were re-optimised to DFT B3LYP 6-31G*, which we use to discuss the energies. Starting at the trans conformer, we find it to be the most stable conformation. As the central bond is rotated, we reach a point where the dihedral is 90o, and a maximum in the energy profile, 7.56 kcalmol-1 higher in energy than the trans conformer. At 90o apart, the π systems are orthogonal, so there can be no conjugation whatsoever. At 0o, the two π systems are coplanar, so the amount of mixing would be at a maximum. Between these two extremes, the orbital overlap becomes less good, so less stabilised due to mixing, and so we see the total energy rise.

As the bond rotates further, we travel down a slope to find another minimum conformer, with a dihedral of 130o, which is 3.54 kcalmol-1 higher in energy than the trans conformer. In this case, we have a balance of opposing interactions; orbital overlap increasing with increasing dihedral angle, but also steric bumping between vinyl protons increasing with increasing rotation. Hence, as the bond is further rotated, the orbital mixing increases, but so does steric bumping, and the steric repulsion is a stronger effect than the orbital mixing , so we see an energy rise, to another maximum, where the vinyl termini are co-planar, i.e the cis-isomer, which is in fact a transition state, not a stable conformer, and is 3.88 kcalmol-1 higher in energy than the trans-conformer.

|

Diels Alder Reaction Reactant Energies /DFT B3LYP 6-31G* |

||

|

Reactant |

Energy /Eh |

Energy /kcalmol-1 |

|

Ethene |

-78.58746 |

-49314.416 |

|

trans-butadiene |

-155.99213 |

-97886.627 |

|

130o-Butadiene |

-155.9864836 |

-97883.07832 |

|

cis-Butadiene |

-155.9859496 |

-97882.74324 |

|

90o-Butadiene |

-155.980091 |

-97879.06687 |

Product

We also expect cyclohexene to have several minima. Unfortunately, any potential surface scan to find conformations would be long and complex, because more than one bond rotation is required to convert between any minima. However from our knowledge of cyclohexane conformation, we can make some educated guesses as to what will be the stable minima, then we shall test our predictions by optimising to try to find these structures.

From our knowledge of cyclohexane conformation, but taking into account to geometry constraints imposed by the double bond, we can imagine two minimum conformations for cyclohexene, a half-chair and half-boat form. We will now perform optimisations

on guess-structures described to attempt to show this prediction to be true. A half-chair cyclohexene structure was created by taking chair-cyclohexane, and adjusting the bonds and valences as necessary. A half boat structure was created by taking a bicyclic system, and removing one CH2CH2 group, and then adjusting bonding and valency. These guess structures were optimised initially to HF 3-21G theory, then the result to DFT B3LYP 6-31G*. As we predicted, these are both minima, and the half chair is indeed lower in energy, by 5.74 kcalmol-1.

|

Diels Alder Product Energies /DFT B3LYP 6-31G* |

||

|

Conformer |

Energy /Eh |

Energy /kcalmol-1 |

|

Half-Chair Cyclohexene |

-234.6482949 |

-147244.1516 |

|

Half-Boat Cyclohexene |

-234.6391542 |

-147238.4157 |

Optimising the Transition State

To find the Transition state for our prototype Diels Alder Reaction, our optimised structures of ethene and cis-butadiene were taken, and added to one frame of a mol-group. The ethene was positioned above the plane of the cis-butadiene, in a geometry so when the QST2 calculation interpolates the atomic positions between this starting point and optimised chair-cyclohexene, we would hope to find the expected transition state. The atomic labeling was changed between the two, so as to allow the atoms to map onto each other. This was run to HF 3-21G theory initially, then to DFT B3LYP 6-31G*. The resulting checkpoint file is shown below.

|

Diels Alder Reaction QST2 |

|||||

|

Start Point |

End Point |

Result |

|||

|

|||||

Initially, the result looks quite a mess, but if we look at the vibrational frequencies we find we have an imaginary mode of magnitude 818cm-1 in HF theory. When we changed to B3LYP theory, the energy of this mode was 525cm-1. Animating this mode, we find it is indeed the characteristic bond forming reaction. We found the transition state. Using Gaussview to clean the above structure, and animating this mode. The odd-bonding is just a relic of the interface. The fragments are positioned 2.21Å apart in the transition state.

|

Diels Alder Transition State Cleaned Geometry and Imaginary Mode Animation |

|||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Diels Alder Transition State Energy |

Energy /Eh |

Energy /kcalmol-1 |

|

DFT B3LYP 6-31G* |

-234.5438966 |

-147178.6405 |

Following the reaction pathway

Once the transition state had been found, an IRC calculation was carried out, to HF 3-21G theory. Unlike the Cope rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene, the reaction profile is asymmetric, so we specified the calculation to travel in both directions, calculating the force constant at every step. Plotting the system electronic energy against reaction coordinate, we obtain the energy profile for the reaction.

We see initially that the butadiene starts in a non-planar cis-conformation, and he first necessary atomic displacement in the reaction is to become planar. Then the ethene approaches the π system, where we see the hydrogen atoms bend back away from the forming bond. The product is in the half-boat conformation, which we said is a very high energy minima, only slightly lower than the transition state between half-chair and half-boat, so quickly we would expect the ring to rearrange to give the more stable half-chair conformer.

To calculate the activation energy for this reaction, and now, also the free energy of reaction, we need to re-optimise our HF 3-21G results to DFT B3LYP 6-31G*, and then compare to the lowest energy (by convention) conformers of reactants and products. This will be the trans-butadiene and the half-chair cyclohexene. The calculated activation energy is 22.4 kcalmol-1. The calculated enthalpy change of reaction is -43.1 kcalmol-1.

The Diels Alder Cycloaddition between 1,3-Cyclohexadiene and Maleic Anhydride: Regioselectivity

Orbital Symmetry

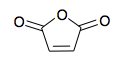

[1] [2] Maleic Anhydride is an electron poor alkene, because the ester function withdraws electron density from the double bond. This results in the π orbital, which in many alkenes is normally our HOMO, being moved to HOMO-2, because of the stabilising nature of the resonance with the ester. The HOMO is mostly of carbonyl oxygen lone pair character.

|

Maleic Anhydride |

|||

|

Orbital: |

HOMO-2 |

HOMO |

LUMO |

|

Form: |

|||

|

Symmetry: |

S |

A |

A |

The 1,3-cyclohexadiene is a slightly electron rich diene, by virtue of electron pushing alkyl groups. However, when we look at the minimum energy conformer of 1,3-cyclohexadiene (puckered, see below), we find that the molecule itself is not symmetric about a plane bisecting the molecule. Hence, its orbitals will not be either. In this case, we can say that to get a reaction, the diene must first become planar. Only then will mixing occur between that and maleic anhydride FOs, which is symmetric about a plane. Hence, we shall visualise the FOs of planar (the TS of the ring flip, see below) 1,3-cyclohexadiene, as this is the geometry to react, and treat the symmetry allowed combinations of these FO's. The orbitals are very much like the cis-butadiene orbitals, ie. The HOMO is of the two alkene π orbitals, which is antisymmetric with respect to the plane, and the LUMO is π* of the two double bonds, and is symmetric about the plane.

|

Planar (TS of ring flip) 1,3-Cyclohexadiene |

|||

|

Orbital: |

HOMO |

LUMO |

|

|

Form: |

|||

|

Symmetry: |

A |

S |

|

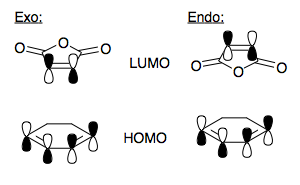

This pair then and perfectly set up to react with the high energy diene HOMO overlapping with the low energy dienophile LUMO, i.e normal electron demand.[3] Comparing the symmetry of these FOs (planar cyclohexadiene), we find them to both be antisymmetric with respect to the plane. This is a symmetry allowed combination, and hence will result in a large stabilisation. We can form our guess of the transition state structure, again, with the dienophile approaching from a face-on, rather than end-on direction, so the π/π* orbitals meet end on. We now however, have an issue of regioselectivity. Before, there was no 'way around' for the ethene, whichever allowed orientation it approached in was the same. Now, the maleic anhydride can approach the diene in two orientations which abide to the symmetry of the plane. These lead to exo- and endo-isomers of the product adduct. We form our transition states guesses:

And compare to the form of those computed:

|

Exo-TS |

Endo-TS |

We see that they are indeed antisymmetric with respect to the plane. The form is complex, because, as we saw, the LUMO of the maleic anhydride was not simply π* of the alkene, but also of the carbonyl.

We will also see that the endo transition state is lower in energy than the exo transition state. Above, we have drawn the FOs involved in the bond forming overlap, but we have neglected to consider what the other orbitals may be doing. The LUMO of the dienophile is also heavily carbonyl π* in character, as well as the alkene π*. In the endo-transition state, this π system sits over the newly forming alkene, and they can form a symmetry allowed combination. Because this is a HOMO/LUMO interaction, the result is an overall stabilisation of the system. This secondary orbital overlap explains the observed endo-selectivity. The Exo-form has this π system removed, so there can be no overlap.

Optimising Reactants and Products

We carry out our ordered procedure once more, initially optimising reactant and product geometries, initially to HF 3-21G, then to DFT B3LYP 6-31G*. Guess fragments were created using Gaussview 3.09, then optimising to theory. Once again, absolute energies given in a table below, energy changes discussed.

Maleic Anhydride is necessarily planar, so there is not conformational freedom to concern us.

1,3-Cyclohexadiene could be either planar, which would maximise stabilising conjugation between the diene, but at the same time maximising staggering destabilising interactions in the CH2CH2 unit. Some puckering would reduce the staggering, but also the conjugation. We shall therefore form two guess structures for these conformers, and optimise. Creating a planar structure, and optimising from there, we receive a planar structure back. But analysis of the vibrations shows us that this is in fact a transition state we have found, by accident, with one imaginary mode of magnitude 154cm-1! Animating the vibration, we find that it is the puckering of the CH2CH2 group to lower the staggering, as we discussed. Optimising to a puckered geometry, we find this to be a stable conformation. Running an IRC calculation starting from the planar transition state confirms that this leads to the puckered minimum, with a symmetrical reaction profile, as expected, since puckering in either way is equivalent. The barrier to this ring flip is minimal, and easily passed with thermal energy.

There are two diastereoisomeric products, formed from different transition state geometries, which we will explore next. These are the endo- and exo- adducts. Guess fragments were created from a bicyclic fragment, and carbon tetrahedral fragments, then adjusting the bonding and valency accordingly in Gaussview, and these optimised. The two isomers are very similar in energy, with the endo-isomer being only 1.62 kcalmol-1 lower in energy than the exo-isomer. This is because the two products are very similar, but in the exo-isomer there is some small steric bumping between the CH2CH2 H atoms and the O atoms of the Maleic Anhydride fragment. The results are shown below.

|

Reactant and Product Energies /DFT B3LYP 6-31G* |

||

|

Molecule |

Energy /Eh |

Energy /kcalmol-1 |

|

Maleic Anhydride |

-379.2895447 |

-238007.9822 |

|

Puckered 1,3-Cyclohexadiene |

-233.4189323 |

-146472.7142 |

|

Endo-Product Isomer |

-612.7582899 |

-384511.9545 |

|

Exo-Product Isomer |

-612.7557845 |

-384510.3823 |

Optimising Transition States

As we did for the Butadiene/Ethene Diels Alder cycloaddition, a QST2 TS opt was used to find the two transition states. A guess geometry was created for the start point, to allow the interpolation between this structure and the corresponding product isomer to give the transition state. A molgroup was created, and the numbering changed accordingly.

|

Diels Alder Reaction between Maleic Anhydride and 1,3-Cyclohexadiene QST2 |

||||||

|

Starting Point |

End Point |

Result |

||||

|

Exo-Isomer |

|

|||||

|

Endo-Isomer |

|

|||||

Once again, we see the dienophile approach from above the plane of the ring, a requirement for an allowed reaction to preserve the symmetry with respect to the plane. The exo-TS is 2.56 kcalmol-1 higher in energy than the endo-TS, which, as we saw in our discussion above, is due to a favorable, stabilising secondary orbital overlap between the maleic anhydride carbonyl π system, and the forming double bond, in this transition state.

|

Transition State Energies /DFT B3LYP 6-31G* |

||

|

Transiton State: |

Energy /Eh |

Energy /kcalmol-1 |

|

Endo: |

-612.6833966 |

-384464.9582 |

|

Exo: |

-612.6793109 |

-384462.3944 |

Following the reaction pathway

On the structures found to be transition states from the QST2 calculation, an IRC calculation was carried out to HF 3-21G theory, for each diastereoisomer. The resulting reaction profiles are shown below.

Initially, to react, the puckered 1,3-cyclohexadiene has to become planar, which we saw is a transition state for the ring flip, which requires a rise in energy, seen in the plot. As the reactants move together, the energy quickly rises, due to steric and electronic repulsion. We see that the exo transition state is at a higher energy than the endo transition state. The product energies are almost comparable, as we saw, but the endo-isomer is very slightly lower. Because the endo transition state is lower in energy and the product has a lower energy, the endo-isomer is both the kinetic and thermodynamic product of this reaction.

All that remains to be done is to reoptimise our transition states and reactants and products to DFT B3LYP 6-31G* to report a calculated activation energy and free energy of reaction. The activation energy for the Endo pathway is calcuated at 15.74 kcalmol-1. That for the exo pathway is calculated at 18.30 kcalmol-1. This explains the endo-selectivity under kinetic reaction conditions. The free energy change on reaction for the endo pathway is calculated to be -31.26 kcalmol-1. That for the exo-pathwas is at -29.69 kcalmol-1. Hence, the endo pathway is also favoured under theromdynamic conditions.

We should note that all the energies reported here are from calculations on the free, isolated molecules. Diels Alder reactions can be influenced by the solvent, though usually less than ionic species. Hence, we could include a solvation model in our calculation, to correct for this.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 http://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/local/organic/pericyclic/

- ↑ T.L.Gilchrist, R.C.Storr, Organic Reactions and Orbital Symmetry, 1972

- ↑ A.C.Spivey, Heteroaromatic chemistry Lecture Course, 2010

General references made throughout to:

M.Bearpark, https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=Mod:phys3, 2008

J.B.Foresman and A.Frisch, Exploring Chemistry with Electronic Structure Methods, 1996