Rep:Mod:aoz15MgO

The Free Energy and Thermal Expansion of MgO Computational Lab

by Aleksei Zaboronsky. CIDː 01064961.

Abstract

Some materials expand upon being heated. This process of thermal expansion is an important, intrinsic property and needs to be understood when dealing with materials, particularly in engineering contexts. This practical investigated, amongst other properties, the thermal expansion of an MgO crystal lattice. This was done using computational modelling, and compared two methodsː the quasi-harmonic approximation and the molecular dynamics method. The former was found to work well at lower temperatures due to considering the zero-point energy of the lattice but fell apart at higher temperatures due to not considering anharmonicity, whilst the latter did consider anharmonic effects but did not consider the zero-point energy and so was a poor model at low temperatures. The thermal expansion coefficient values obtained were 29.4 x 10-6 and 31.3 x 10-6 K-1 for the two methods respectively.

Introduction

Properties of materials can be investigated by analytical computational methods in such a way that could not be done otherwise without performing the experiments in real-life, and in a much shorter time frame. This practical looks to investigate an MgO crystal lattice via such methods. The properties investigated include the free energy of the lattice and its volume. The experiment also aims to compare the quasi-harmonic and molecular dynamics methods when determining the thermal coefficient of expansion of an MgO lattice and see how the two perform at a range of temperatures.

Harmonic and Quasi-Harmonic Approximations

To discuss the QHA (quasi-harmonic approximation), the harmonic approximation must first be mentioned. The harmonic approximation is a simple model for crystals which considers only nearest-neighbour interactions between atoms. The atoms are taken to vibrate and, if this motion is small compared to their atom-atom separation, the energy of a monoatomic chain can be found by summing over all the atoms bythe use of a Taylor Series. The Taylor Series expansion is taken up to the quadratic term, and all higher order terms are ignored, therefore modelling the lattice as a periodic set of harmonic oscillators. Due to the exact solution obtainable from harmonic equations of motion, the harmonic approximation is convenient to use and capable of yielding good results as well as many of the system's major properties. Since atomic motion is reduced at lower temperatures, due to lower kinetic energy, the approximation works particularly well at lower temperatures, and only breaks down significantly at higher temperatures. This break down is due to the approximation not factoring in anharmonic effects[1].

By application of Newton's 2nd Law of Motion and the Born-von Karmen periodic boundary condition - linking together the ends of the monoatomic chain to ensure each atom has two nearest neighbours - the motion of the entire chain can be modelled as a linear superposition of travelling waves[1]. The angular frequency wk for this can be found viaː

(Equation 1)[1]

where J is the harmonic force constant, m is the atomic mass, k is the wave vector and a is the atomic separation. Plotting of wk against the reciprocal lattice unit cell a* gives a dispersion curve. In terms of atomic separation a,

(Equation 2)[2]

The model is easily extendable to higher dimensions by dealing with atomic planes, not individual atoms, when considering atomic displacement and calculating forces and force constants in a way that reflects this. Whilst the harmonic approximation does have shortcomings, such as breaking down at higher temperatures and only being valid for constant volume, it is a very useful initial tool when analysing simple crystal lattice systems. It allows the finding of major thermodynamic properties of a system, as well as the calculation of phonon DOS (density of states). In this experiment, this methodology is used to find the phonon dispersion and DOS curves seen. However, when investigating variables such as thermal expansion, the model needs to be altered to take into account cases for which the volume is not kept constant throughout. The QHA does this by analysing frequency dependence on the volume and structure of the crystal system. For lattice dynamics, the quasi-harmonic approximation uses the harmonic approximation for all cells within the crystal but considers the frequencies to be volume dependent[1]. This given set of frequencies calculated by the approximation is used to find the corresponding volume and hence can be used to determine factors such as the thermal coefficient of expansion. The minimum free energy is found by following the consideration that, for a given temperature, the equilibrium structure is that with the minimum free energy. The Helmholtz free energy is found via the following equationː

(Equation 3)[1]

In this equation, the first term corresponds to the internal energy contribution, the second to the zero-point energy and the third accounts for vibrational contributions. Due to the quasi-harmonic and harmonic approximations not being able to factor into account anharmonic interactions, they cannot be used to model displacive phase transitions, since these stem from intrinsic anharmonic considerations[1].

The methods discussed here are used for this practical to investigate the variation of several factors of the conventional cell with temperature, notably free energy and volume. These results are compared to those obtained from another simulation method discussed in the next section; the molecular dynamics simulation method.

Molecular Dynamics

The MD (molecular dynamics) method allows scientists to study crystal structures and their behaviours at high temperatures. Unlike the (quasi-)harmonic approximation method, molecular dynamics does take into account anharmonic interactions. The simulation method works by creating a computer-generated set of atoms and then solving Newton's 2nd Law of Motion for their motion. The algorithm creates these atomic arrangements (positions and velocities) at a given time step by using information gained from previous time steps. The computer then compiles the information for all time steps recorded to form classical trajectories for the atomic system over that time period[1]. It is these trajectories that are then analysed.

As with all models, there are certain limitations to the molecular dynamics simulation method. Firstly, computational demands; not only does computational power limit how many detailed simulations can be run in a time-viable manner, it also limits the accuracy of calculated potentials between atoms. For this reason, most molecular dynamics calculations do not include shell models. This often restricts computer modelling to the use of the rigid-ion model. Another limiting factor is run-time; in general, most molecular dynamics simulations run for a far shorted length of time compared to the real-life experimental time. This results in there not being sufficient time for the sample to be truly tested over all spacial dimensions and hence biases the results towards the starting conditions and run-time. This is reflected in the accuracy of results. Finally, as a classical method, the molecular dynamics method can sometimes lead to errors due to not accounting for quantum effects[1].

Nonetheless, the molecular dynamics simulation method is a useful tool in computing structural, dynamic and thermodynamic data for a system and its time-averaged property allows the computation of properties such as the coefficient of thermal expansion.

Coefficient of Thermal Expansion

The coefficient of thermal expansion is an intrinsic property of a material, and relates to how the volume of the material changes with temperature. It is important in many aspects, particularly in engineering; when constructing any structure, it is important to consider how the materials which make it up will respond to changes in their conditions. Should two materials in close proximity with each other expand at drastically different rates (or by a significant amount) at different temperatures, the stress at the boundary could cause the linkage to fracture or shear, jeopardising the structural integrity of the entire structure. Therefore, it is of paramount importance to assess factors such as this when undergoing any such project.

Thermal expansion in a crystal lattice occurs because the energy advantage of the lattice structure having as small a volume as possible is offset by the entropic advantage of lower frequencies and hence a higher volume. Since entropy is temperature dependent, higher temperatures lead to a higher entropic contribution and hence a higher volume; this leads to thermal expansion. Considering this further, the higher energy of the system at a higher temperature results in higher energy phonons being available for population. The filling of these excited states results in more vigorous vibrations for the atoms due to larger displacements from their equilibrium position (higher kinetic energy). This explains the increased entropy in the expansion. The coefficient of this process, ,is defined in equation 4, and is the rate of change of volume with respect to temperature for a constant pressure system. This term is normalised by dividing through by the initial volume Vo.

(Equation 4)[3]

Experimental

All experimental work performed in this experiment was done so via computational modelling. The GUI (graphical user interface) used was DLVisualize. For running the simulations, the GULP (General Utility Lattice Program) for the molecular modelling code was used. For all simulations performed, the ionic.lib option was selected in the GULP Potential Parameters panel. In the same panel, the Include Shells option was not selected.

Calculating MgO Phonon Modes

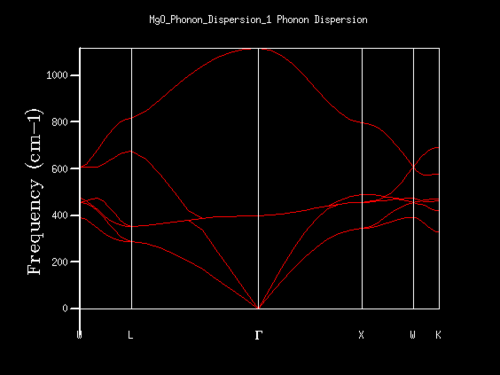

The phonon dispersion curves for MgO were found and plotted using the Phonon Dispersion setting in the execute GULP panel. By examination of these curves, it wad found that point L corresponded to the single k-point for the DOS (density of states) for a 1x1x1 grid.

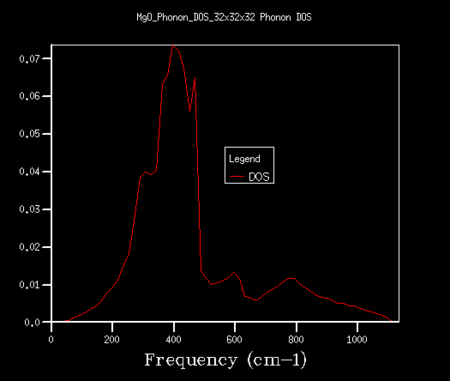

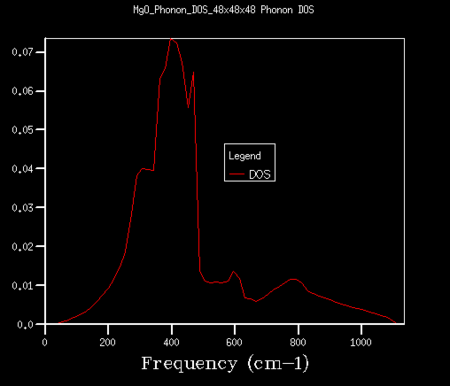

The DOS for the phonons was found using the Phonon DOS setting on the execute GULP panel. This was initally performed for shrinking factors of A = B = C = 1 (a 1x1x1 grid). All shrinking factors being kept equal, they were then increased by steps of one to a 10x10x10 grid and then by larger increments to a 64x64x64 grid size. The DOS data collected was graphically plotted and used to find a minimum grid size which yielded a reasonable DOS approximation. This grid size was found to be 32x32x32.

Calculating the Free Energy of MgO

When calcuating the free energy of MgO within the quasi-harmonic approximation, the same grid of points was used as to plot the previously found phonon DOS. A suitably-sized k-space for free energy convergence was found by varying grid size (shrinking factors) and recording the free energy for each. This operation was performed via the Phonon DOS setting on the execute GULP panel, with a temperature of 300 K and a pressure of 0 Pa. With all of the shrinking factors set equal, the free energy was found for grid sizes from 1x1x1 to 10x10x10 with increments of 1 and then up to 64x64x64 with larger increments. It was determined that the grid sizes 2x2x2, 2x2x2 and 3x3x3 were found to be appropriate for calculations of free energy accurate to 1, 0.5 and 0.1 meV per cell respectively.

The Thermal Expansion of MgO

The free energy and conventional cell volume of a 32x32x32 sized grid were found for varying temperatures. This was done by using the Optimisation setting on the execute GULP panel and using the Phonon DOS interface to set the shrinking factors to 32. To investigate the properties of MgO at higher temperatures, the temperature was varied from 0 to 2900 K in 100 K increments. For each reading, the output log file was used to extract the final free energy and primitive cell volume values. This volume value was multiplied by four to find the corresponding conventional cell volume. This value was cube rooted to find the lattice constant. The coefficient of thermal expansion was found by use of equation 4 and the gradient of volume vs. temperature graphs for different regions.

Molecular Dynamics

When running these calculations to find how cell volume changed with temperature, a supercell containing 32 MgO units was used. This cell had a volume eight times higher than a conventional cell and was used to allow more vibrational flexibility. The Molecular Dynamics part of the execute GULP panel was used and the ensemble was set to NPT. This setting fixes the particle number, external pressure and temperature of the system. The time step was set to 1.0 femtoseconds, the equilibrium and production steps to 500 and the sampling and trajectory write steps to 5. The temperature was varied from 100 to 3500 K in steps of 100 K to investigate the properties of MgO at, and above, its melting point (3125 K)[4]. For each run, the averaged cell volume for the final time step was recorded. This volume was divided by eight to find the corresponding conventional cell volume, and then cube rooted to find the lattice constant. As with the corresponding step for the quasi-harmonic approximation, the thermal expansion coefficient was found via equation 4.

MgO Structure

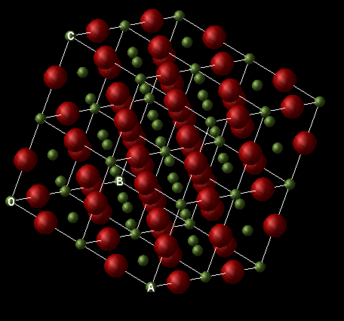

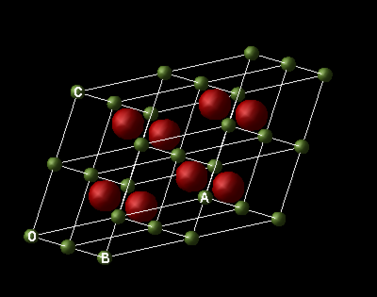

An MgO crystal has an fcc (face-centred cubic) lattice structure for its conventional unit cell[4]. This cell contains eight atoms; four magnesium and four oxygen. It places these atoms on each vertex and face of a cube. All of its lattice constants are equal and it has internal angles of 90°. However, the structure can also be represented using a primitive unit cell. This cell is a rhombohedron with 60° internal angles, and contains only two atoms; one magnesium and one oxygen. The conventional cell better reflects the symmetry of an MgO crystal lattice, and is therefore most often referred to in experimental studies. However, the computer optimisation outputs the primitive unit cell result. This is not an issue, since the two cells have the same density and are therefore easily inter-converted between. Hence, when calculating the volume of a conventional cell, the volume of the primitive cell is simply multiplied by four. Figures 1 and 2 show the 2x2x2 cells for the conventional and primitive unit cells respectively, as modelled computationally.

|

|

Results and Discussion

Phonon Dispersion Curves and Density of States

As described in the experimental section, the phonon dispersion curves and phonon DOS plots were generated computationally using the GULP panel. Figures 3 and 4 below show the phonon dispersion curves and the DOS plot for a 1x1x1 grid respectively. The single k-point for which the 1x1x1 grid DOS was calculated can be determined to be point L as seen in figure 3. By looking at the DOS plot it is clear, from the four peaks, that there are four vibrational frequencies present for this grid size. By looking at their densities, it can be concluded that the two lower frequency signals (the acoustic modes) are doubly degenerate compared to the two higher frequency signals (the optical modes). Hence these four peaks correspond to six vibrational bands, two of which are overlapping. Taking this information and analysing the phonon dispersion curves, the frequencies of the peaks on the DOS plot correspond to the frequency values found at point L. The double degeneracy can also be confirmed on the plot by noting the double branches on the dispersion curves plot for the two lower frequencies (at approximately 290 and 350 cm-1). Looking at the output dispersion curves Log file, it confirms that the frequencies at point L match those from the DOS plot and locates the k-point to be at coordinates (0.5, 0.5, 0.5) in k-space. From this relationship, it is clear how useful DOS plots can be used when working with dispersion curves and vice versa; the DOS allows dispersion curves to be summarised by averaged over all k-points and giving the density of modes[2].

|

|

Increasing the grid size by altering the shrinking factors results in a higher number of vibrational bands over a wider spread of frequencies. As the number of k-points being sampled therefore also increases, more phonons are displayed on the DOS plot, and this results in a continuous curve as opposed to the separate peaks seen in figure 4. As the grid is increased further, a truer picture of the DOS is obtained. The grid size was increased step-wise from a 1x1x1 grid until a smooth, true curve was found. This was found to be for a 32x32x32 grid, and is shown in figure 5. The difference between this plot and that seen in figure 4 is drastic. DOS plots were also found for higher grid sizes, such as 48x48x48 (see figure 6). However, at this point the features of the curve changed only by insignificant amounts and hence, due to the shorter run time, a 32x32x32 grid was chosen as the compromise between the DOS plot accuracy and time efficiency. Above this point, the extra information gained from the curves was not deemed justifiable for the extra time required to run the simulation.

|

|

Free Energy as a Property of Grid Size

The lattice free energy variance with grid size was computed. The plot for this energy variance can be seen in figure 7, where the red dotted line shows the final, converged energy value. From the graph it is clear that the energy converges quickly, the free energy being accurate to 1 meV for a 2x2x2 grid. The reason for the energy value being more accurate for a larger grid size is due to more k-points in the reciprocal lattice space being considered and hence having more information about the cell phonons. This in turn gives more information about thermodynamic properties such as the entropy and energy. Therefore, since there is more information about them, they can be calculated to a higher accuracy[2]. Table 1 also shows the free energy variation with shrinking factor size. The third column shows the difference between the converged energy value and the energy at that grid size. From this column, it can be seen that a 2x2x2, 2x2x2 and 3x3x3 grid is needed to be accurate to 1, 0.5 and 0.1 meV respectively.

| Grid Size | Free Energy / eV | Difference from Converged Value |

|---|---|---|

| 1x1x1 | -40.930301 | 0.003818 |

| 2x2x2 | -40.926609 | 0.000126 |

| 3x3x3 | -40.926432 | 0.000051 |

| 4x4x4 | -40.926450 | 0.000033 |

| 5x5x5 | -40.926471 | 0.000012 |

| 10x10x10 | -40.926480 | 0.000003 |

| 16x16x16 | -40.926482 | 0.000001 |

| 20x20x20 | -40.926483 | Converged |

| 32x32x32 | -40.926483 | Converged |

The converged free energy, to the maximum precision computationally possible of 0.000001 eV, was found to be -40.926483 eV. At this value, it is no longer useful to increase the grid size, since any higher precision is redundant and not relevant to further calculations for this program. A higher grid size would also increase run time and hence decrease time efficiency. Table 1 shows that, unlike for the DOS plots, the free energy has converged by the time a 20x20x20 grid is reached, meaning that using a 32x32x32 grid is obsolete for this calculation and needlessly wastes computational processing power.

When comparing optimal grid sizes for determining DOS plots and free energies for MgO to other materials, the most important factor to consider is the size of the reciprocal space. This can be determined by using equation 2 and realising that the reciprocal lattice unit cell a* and the lattice constant a have an inverse relationship. Therefore, for a system with a significantly smaller a value than for MgO, the reciprocal space will be much larger and will likely require larger shrinking factors (a larger grid) to sufficiently sample enough phonons to obtain a smooth DOS plot. Only at this point will it be worthwhile to run simulations to find thermodynamic properties accurately. The opposite is true for a system with a significantly larger a value.[2]

CaO forms a very similar lattice as MgO, due to calcium and magnesium being in the same group in the periodic table. As of such, CaO also forms an fcc structure. Ca2+ cations are slightly larger than Mg2+ cations, however, and so CaO has a slightly larger lattice constant (4.80 Angstrom as compared to 4.21 Angstrom for MgO[4]). As of such, it could be assumed that a smaller grid could be used. However, the difference between the two structures is very small for such calculations due to their ionic and structural similarities. and hence it is logical to assume, even though there is a small size disparity, that an optimally sized grid for MgO would be appropriate for a corresponding CaO structure.

A Zeolite, such as Faujasite, is a much more complex structure and has a much larger value of a. Hence, using the previously mentioned inverse relationship, the system has a much smaller reciprocal lattice unit cell and so a smaller grid size than one used for MgO would be appropriate to use to obtain sufficient phonon information to run simulations successfully and generate a smooth DOS plot.

A metal, such as lithium, partakes in metallic bonding, in which there are free, delocalised electrons throughout the structure and strong electrostatic attractions between atoms. As of such, the system has a much smaller lattice constant than that of MgO and so would require larger shrinking factors to appropriately model.

Use and Comparison of Modelling Methods

The quasi-harmonic approximation was used to compute the Helmholtz free energy for a 32x32x32 sized grid. The energy was found at temperatures from 0 to 2900 K in 100 K steps and is plotted in figure 8. The relationship found is decreasing Helmholtz free energy with increasing temperature. This decrease is initially non-linear but becomes linear as the temperature rises. The Helmholtz free energy depends on temperature via the following relationː

(Equation 5)[5]

where A is the Helmholtz free energy, U is the internal energy, T is the temperature and S is the entropy. Equation 5 helps to explain why the free energy decreases as temperature increases; as temperature is increased, the entropic term becomes dominant. Since the temperature is in kelvin and the entropy is absolute entropy, both the T and S terms are always positive. Therefore, as temperature rises and the TS term becomes dominant, the free energy will become more negative. Making the assumption that the internal energy and entropy terms do not change significantly with temperature would explain the shape of the curve; initially both are still of the right order of magnitude to affect the overall shape of the curve, resulting in the non-linear initial region. However, as the temperature increases, U and S do not comparatively change by as much and hence the energy decrease becomes linear due to the free energy effectively being proportional to temperature and hence becoming a straight line with a negative gradient.

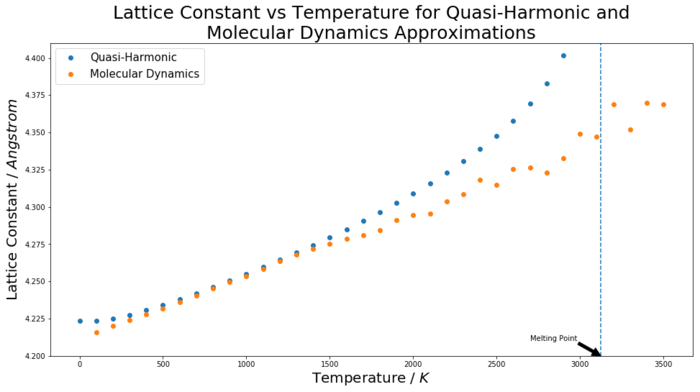

The conventional unit cell volume as a function of temperature was recorded using both the quasi-harmonic approximation and molecular dynamics methods. For the QHA, the volumes outputted by the simulation were multiplied by four to convert from a primitive to a conventional unit cell, and for the MD simulation, the outputted volumes were divided by eight to convert from the supercell to a conventional unit cell. With these volumes normalised, and hence comparable, they were then cube-rooted to obtain lattice constant values. For the two methods, these values were plotted on the same axes for comparison, as seen in figure 9. The melting point of MgO is labelled on the graph to provide some indication as to the behaviour of each modelling method at, and near, a phase transition.

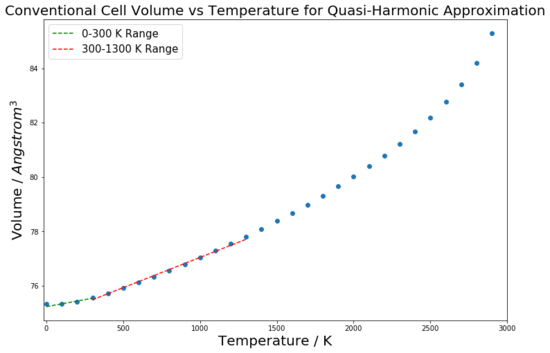

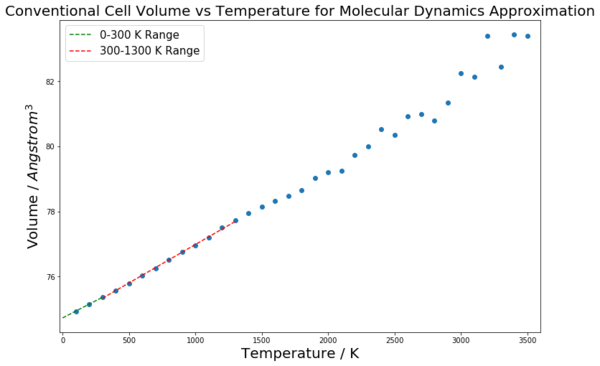

This curve seen in figure 9 has the same properties and shape as the curve but for volume against temperature, due to the lattice constant simply being the cube root of the cell volume. However, for the calculation of the coefficient of thermal expansion, the volume plot was used. This is because, as seen in equation 4, the coefficient of thermal expansion depends on a material's volume dependence on temperature. Hence, for a linear region on a volume-temperature graph, the coefficient can be calculated by finding the gradient for that region and then normalising it by dividing through by the volume at the initial temperature for the fit. This process is shown in figures 10 and 11 for the QHA and MD methods respectively. The curves have been fitted for two temperature ranges: 0 - 300 K and 300 - 1300 K. The thermal expansion coefficient values found from these linear regions have been compared to each other, and literature values, in table 2.

|

|

| Temperature Range / | Quasi-Harmonic Approximation / | Molecular Dynamics / | Literature / |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 - 300 | 13.7 | 28.2 | 10.4 |

| 300 - 1300 | 29.4 | 31.3 | 31.2 |

There are several interesting points to consider from these results. A logical way to analyse the success of these models is to consider three temperature regions independently to see how the approximations perform in each; low (0 - 300 K), middle (300 -1300 K) and high (above 1300 K) temperature regions. At low temperatures, the thermal coefficient value found by the quasi-harmonic approximation was close to the literature value, suggesting that it provided a realistic model of the crystal lattice. The molecular dynamics value was far out, and totally misrepresents the system at low temperature conditions. The reason for this disparity between the two methods for this range is that only the QHA considers the zero-point energy of the system. At low temperatures, this is an important energetic contribution and hence results in the MD method, which does not consider the zero-point energy, giving a highly inaccurate value. The MD method in fact models the low temperature region in the same way as the middle temperature region, hence the low temperature value is close to the middle temperature range value. This is because it is a classical method and hence ignores quantum effects such as the zero-point energy, so gives a straight line[1]. Equation 3 shows the energy calculation for the QHA; the second term is the zero-point energy term.

For the middle temperature regions, both approximations yield accurate values. However, the molecular dynamics result in particular is very close to the literature value. It is not surprising that both models give a good approximation for the 300 - 1300 K region, since it is a linear middle region which is not near any phase changes for the material and the methods are designed to model it. The QHA works well in this region because the material fits the harmonic approximation closely in this region.

For the higher temperature region, no thermal coefficient region literature could be found. However, the models can still be assessed based on known behaviour of materials when they reach higher temperatures near phase transitions. At this point, above a temperature of approximately 2000 K, the QHA begins to quickly steepen and increase in volume. This is not a fair reflection of reality and occurs because the approximation does not take into account the anharmonic effects associated with phase transitions. Instead, the model assumes the harmonic approximation and therefore follows a parabolic function, which would never result in bond dissociation. Therefore, since at higher temperatures it still assumes the crystals are in an ordered lattice, the QHA is not suitable for use, and in fact breaks down to the degree that the computer simulation outputs an error when being run for temperatures of 3000 K or higher. This is because the parabola model does not calculate a volume (or lattice constant) for such a temperature, and fails to consider the increased entropic term present at this higher temperature. The MD method, however, does take into account anharmonic interactions and hence does a better job of modelling the crystal lattice at higher temperatures. The stark contrast between the two methods can be clearly seen in figure 9 when the two lines begin to split at approximately 1500 K and are totally separated at 3000 K. It can be seen that the molecular dynamics method does begin to fluctuate significantly at temperatures above 3000 K and above the melting point. This is due to how the method works; as mentioned in the introduction, the molecular dynamics method works off of a step wise algorithm. At higher temperatures near the melting point, the kinetic energy of the system is very high, and hence the velocities of the atoms being modelled are too. This means there is more scope for error when calculating the new positions and velocities and so results in larger fluctuations in the volumes calculated.[1][5]

For a diatomic molecule with exactly harmonic potential, the equilibrium bond length would not be expected to increase with temperature due to the potential being in a harmonic well. This is not the case for the QHA, which is clear from the fact that it does model thermal expansion, which is a process involving the bong length increasing. The reason that this does occur with the QHA is mentioned in the introduction, and is due to the approximation considering phonons, which are volume dependent. Therefore the approximation also has a volume dependence and does predict that the bond length will increase with increased thermal energy.

Conclusion

The experiment successfully used computer simulations, run through the GULP, to investigate an MgO crystal lattice structure and its properties. This included the plotting of phonon and density of states plots. Upon plotting the density of states, it was determined that a 32x32x32 grid size resulted in a sufficiently good enough curve whist still completing simulations within a reasonable time frame. By analysis of the 1x1x1 density of states plot and comparison with the phonon dispersion curves, it was seen that the k-point for the 1x1x1 grid corresponded to point L on the phonon dispersion curves. Investigation into the Helmholtz free energy variation with grid size saw that the energy converged quickly as grid size was increased and that a 20x20x20 grid was sufficient for full convergence. The lattice free energy was investigated as a function of temperature and found to decrease due to an entropic term dominating at higher temperatures.

A large part of the practical focused on comparing the quasi-harmonic approximation with the molecular dynamics method, and this was done by investigating the thermal expansion of MgO. Both methods were shown to work better in certain temperature ranges; the quasi-harmonic approximation was better suited at low temperatures due to considering the zero-point energy of the lattice, a quantum term which the classical molecular dynamics model does not account for. However, at high temperatures the quasi-harmonic approximation broke down due to not factoring in anharmonic effects. The molecular dynamics method does factor these in, and hence did not break down, giving a truer representation of the behaviour of MgO at and around its melting point. At the higher temperatures, the molecular dynamics data did get noisy, which it was hypothesised to be due to the increased kinetic energy of the atoms resulting in more potential for error in the step wise algorithm. An interesting further experiment would be to look at whether altering the time step and giving the method more time to calculate velocities and positions would result in a less noisy region at higher temperatures. For the 300 - 1300 K range, the quasi-harmonic approximation and molecular dynamics models gave thermal expansion coefficient values of 29.4 x 10-6 and 31.3 x 10-6 K-1 respectively. These answers were both near the literature value[6] of 31.2 x 10-6 K-1, suggesting that both models are appropriate to use for this range.

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 Dove, M.T., Introduction to Lattice Dynamics, Cambridge University Press, 1993, chapters 2, 8 and 12.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Misra, P., Physics of Condensed Matter, Academic Press, 2010, chapter 21.

- ↑ Harrison, N., Vibrations in Crystals, Lecture 4.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Börnstein, R., Landolt, H., Semiconductors: Semimagnetic Materials, Landolt-Börnstein Group III Condensed Matter, 2011, vol. 41B, pp 1-6

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Atkins, P., De Paula, J., Atkins' Physical Chemistry, Oxford University Press, 2014, 10th ed., chapters 3 and 12.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Anderson, O.L, Zou, K., Thermodynamic Functions and Properties of MgO at High Compression and High Temperature, Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data, 1990, 19, pp 69