Rep:Mod:Zm714

Computations of the thermal expansion of magnesium oxide using the quasi-harmonic approximation and molecular dynamics with GULP

Abstract

The thermal expansion, harmonic motions and molecular dynamics of magnesium oxide were investigated using GULP simulations on a DLVisulizer in RedHat Linux. The Helmholtz Free Energy, lattice constant and lattice volume were found to have a linear exothermic increase with increasing temperature between 300 and 1000 K. The thermal expansion coefficient for the harmonic approximations was calculated as 2.6800x10-5 K-1 (4 d.p.), and 2.9880x10-5 K -1 (4 d.p.) for molecular dynamic computations.

Introduction

Crystalline structures may be modelled with band structures. As the cell size and number of atoms within the crystal unit increases, the vibrational energy levels become closer and closer together. These close levels in vibrational energy are called bands.[1] [2]

The vibrational motions within the lattice -the phonons- of magnesium oxide can be estimated by using the quasi-harmonic approximation. The following assumptions must be made to use it:

- The magnesium oxide crystal is perfect and contains no imperfections.

- The magnesium oxygen bond cannot break, no matter their separation from the equilibrium position.

The quasi-harmonic approximation takes into account the internal energy of the lattice structure, the zero point energy of the lattice and the entropic contributions from the vibrations (Eqn. 1 below). [3] [4]

Molecular Dynamics makes use of the movement of the atoms and their movement is not restricted to the equilibrium position. Newtonian mechanics is used to calculate the free energy and volume given other constant variables.

Methodology [3]

Calculations were run using DLVisualize software on RedHat Linux. The calculations were run using a GULP (General Utility Lattice Programme) simulation. This modelled the magnesium oxide crystal using input parameters. All data output (log) files were saved and the data analysed accordingly.

The phonon dispersion curve was created by setting 50 N Points over the k space and then calculating the phonon eigenvectors. For calculating the vibrations of magnesium oxide, the temperature was set at 0 K and the shrinking factors were increased from 1x1x1 to 64x64x64 in increasing factors of 2. The pressure of the simulation was set to 0 Pa. The above was then repeated at 300 K to find the Helmholtz Free Energy and the lattice parameter at each shrinking factor.

The thermal expansion of magnesium was also investigated. The initial optimum crystal structure for magnesium oxide was calculated. This was done over a temperature range of 0 to 1000 K in increasing increments of 100 K. A plot of Free Energy against temperature was created in order to see the overall trend. In addition, graphs of the lattice parameter against temperature were plotted and the volume and temperature curve was also plotted. The latter of these was used to calculate the thermal expansion co-efficient of magnesium oxide between 300 and 1000 K.

The thermal expansion co-efficient was re-calculated when the molecular dynamics of a 2x2x2 cell was used. An ensemble was set such that there was a constant number of atoms, pressure and temperature (NPT) and the volume was allowed to vary with free energy. A time-step of 1 fs was used, and the equilibration and production steps were both set to 500. Calculations were run over a range of 100 to 1000 K (since at 0 K there is no movement in the crystal). A scaling factor of 1/32 was used to allow for a comparison between the two thermal expansion co-efficient values.

Results & Discussion

Lattice Vibrations (phonons) of MgO

Initial Density of States (DOS) v Frequency curves were plotted for a magnesium oxide crystal at 0 K, with varying shrinking factors. These ranged from 1x1x1 to 64x64x64, and all produced different DOS curves (Fig. 1 ).

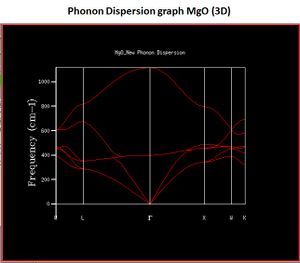

These were then referenced against a calculated phonon dispersion curve (Fig. 2). A phonon dispersion curve shows how the energy of the crystal changes with changing wavevector (k). For example, for a 1x1x1 grid-size, only one k value is considered between and . This gives rise to 4 peaks in the DOS and energy curve. A notable observation about this is that the peaks at 288 and 352 cm-1 are twice as large as 676 and 819 cm-1. This is because these two states are degenerate and so contribute twice as much to the DOS. This corresponds to L in the phonon dispersion curve because 4 branches cross the vertical line. In fact, the two states are degenerate because at a lower wavevector, these two states are not degenerate.

In addition, the number of branches in the phonon dispersion curve is equal to the product of the atoms and number of dimensions. For example, for magnesium oxide, there are two atoms and three dimensions which corresponds to 6 branches; which are clearly visible at the W wave-vector.

From the DOS graphs (Fig. 1), it appears that a 64x64x64 are the best shrinking factors to use. This is because the graph looks very similar to the 32x32x32. In practice, this would be the best one to use, however, the 32x32x32 was chosen because it provides a good compromise on the accuracy and time efficiency of the calculations.

If CaO was under consideration, then there would be no need to change the grid size compared to the MgO one. This is because both magnesium and calcium are group 2 metals and they have the same number of valence electrons. The only difference is that the calcium ion will have a slightly larger ionic radius. For a zeolite, a smaller grid size would be required. Zeolites have a larger number of atoms and therefore a larger cell size. This correlates to a larger 'a' value in direct space. However, reciprocal space needs to be considered and consequently, a larger 'a' value translates to a smaller k value and hence a smaller grid size is required. Lastly, if a pure metal is considered, then the grid size could be smaller. This is because in a pure metal (compared to MgO), there is a sea of electrons surrounding metal ions. When the metal ions vibrate, the electrons will move as well so as to oppose these changes movement. As a result, there is some shielding between the metal ions due to the electrons, and the E(k) values will decrease across the phonon dispersion curve. Consequently, a smaller grid size can be used (as the graph can be more easily resolved).

Interpretation of the Helmholtz Free Energy Calculations

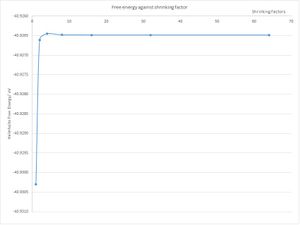

The Helmholtz Free Energy was computed with the GULP programme. Computations were run between shrink-factors of 1x1x1 and 64x64x64 with doubling after each run. The temperature of the system was now set to 300 K (27 Celsius). The plot of the Helmholtz Free Energy with shrinking factor (Fig. 3 and Table 1) shows that the value of the free energy (-40. 926483 eV) starts to converge to 4 decimal places with a shrinking factor of 16. However, an even better approximation is reached at 32 and 64 k values where the value is the same to 6 decimal places. Table 1 shows the values for the free energy with increasing shrinking factors. It is clear that the 4x4x4 and 8x8x8 produce free energies which are appropriate for calculations to 1 meV and 0.1 meV, and the shrinking factors of 16x16x16 and 32x32x32 are appropriate for 0.5 meV.

| Shrinking factors | Free Energy/ eV |

|---|---|

| 1x1x1 | -40.930301 |

| 2x2x2 | -40.926603 |

| 4x4x4 | -40.926450 |

| 8x8x8 | -40.926478 |

| 16x16x16 | -40.926482 |

| 32x32x32 | -40.926483 |

| 64x64x64 | -40.926483 |

The reason why the free energy converges as you move from 1 k point (1x1x1) to 131,072 (64x64x64) is because at each stage, the volume of the lattice is being optimised. This is, in effect, an increase in the resolution of the k space for the crystal. Since it is the Helmholtz Free Energy which was calculated, the temperature of 300 K was kept constant. The dependence of temperature and volume on the Helmholtz Free Energy may be easily derived from the fundamental equations of thermodynamics: (Eqns. 2 - 7 ) [5]

- Where; U: internal energy, q: heat energy, w: work done

- Where; T: Temperature, S: Entropy, P: Pressure, V: Volume

The Helmholtz energy, A, is defined as

and thus

If equations (3) and (5) are combined, then it follows that

Therefore, the Helmholtz Free energy is a function of both Temperature and Volume

A graph of how the Helmholtz Free Energy varies with temperature was also plotted when shrinking factors of 32x32x32 were used(Fig. 4). The graph shows a linear trend between 300 and 1000 K. There is also a non-linear trend between 0 and 300 K because as the temperature approaches 0 K, the vibrations of the magnesium and oxygen atoms decreases, thus decreasing the entropy of the system and hence leaving the system with a zero point energy. This is the energy that the system has at 0 K. Recall that one of the approximations when applying the quasi-harmonic approximation is that the bond between the magnesium and oxygen atoms cannot break and that vibrations occur about the equilibrium position.

Thermal Expansion of Magnesium Oxide

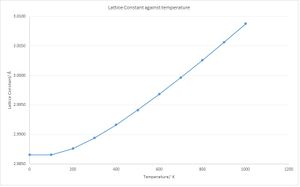

The thermal expansion of magnesium oxide was found by running a GULP calculation. A graph of how the lattice constant varies with temperature was created (Fig. 4)and shows that there is a linear trend between approximately 300 to 1000 K and a non-linear fit between 0 and 300 K. The reason for this is explained in the same way as the Helmholtz Free Energy against temperature curve.

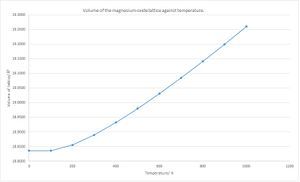

If the lattice constant is converted to the volume of the lattice, then the linear part of the system can be modelled with the equation of the thermal expansion coefficient. (Fig. 5 & Eqn. 8) Manipulation of this equation shows that for changes which are not infinitesimally small, it can be approximated that the partial derivatives are large changes and hence the gradient is equal to the thermal expansion co-efficient multiplied by the initial volume. The thermal expansion co-efficient was calculated as 2.6800x10-5 K-1 (4 d.p.) between 300 and 1000 K. Comparing to literature, the thermal expansion co-efficient at 900 K was recorded as 4.83x10-5 K-1. [6]. The value could be closer to the empirical constant if higher shrinking values were used. The thermal expansion co-efficient tells indicates how the volume of the lattice changes with respect to temperature and is normalised against the initial volume of the crystal.

It is also interesting to note that there are similarities between the volume behaviour of magnesium oxide when heated and ideal gases. In ideal gases, Charles’ Law states that volume of the gas is proportional to temperature.[7] This also yields a linear fit and the gradient shows how the volume changes with temperature at constant pressure; and is non-linear as the temperature approaches 0 K. However, in Charles’ Law, it is assumed that the gas is ideal where as in the simulation of magnesium oxide, there are strong ionic interactions with each magnesium and oxygen atoms.

Molecular dynamics calculations

Computations in molecular dynamics can be used to show how the atoms within the magnesium oxide crystal behave over 1 fs whilst taking ‘snapshots’ of the kinetic and free energy, volume and pressure of the system at a given temperature, pressure and a given number of atoms.

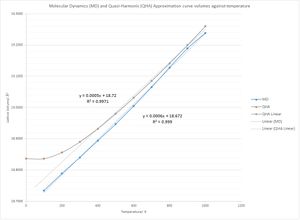

As previously, it was possible to plot a lattice volume against temperature graph. The points between 100 and 1000 K yielded a linear curve and the thermal expansion coefficient was now calculated as 2.9880x10-5 K -1. This value is larger than that calculated from the harmonic approximation. The reason for the difference in these values is because molecular dynamics follows Newtonian physics. In this case, the theory does not take into account the fact that the magnesium oxide crystal will have a zero point energy at 0 K. Fig. 6 shows that the quasi-harmonic approximation returns a value of -40.9010 eV whereas the molecular dynamics line can be extrapolated to 0 for the zero point energy. For this reason, the quasi-harmonic approximation is a better method to use to work out the free energy of the crystal at 0 K.

In addition, at higher temperatures, even though there is no change in the equilibrium position of the atoms, the cell volume will increase linearly with both the Quasi-Harmonic Approximation. This is because there is a greater displacement between the atoms from the equilibrium atoms, and since the assumption is made that the bond cannot break, it can only increase in this way. By contrast, with molecular dynamics, there will come a point where the bonds can break and the atoms can dissociate. This will be at the melting point of magnesium oxide at 3125 K.[8]

Conclusion

The quasi-harmonic Approximation and Molecular dynamics simulations were applied to a crystal structure of magnesium oxide after optimising the shrinking factors of the computation. Various conditions on the simulation were changed including varying the temperature range of the crystal from 0 to 1000 K. The data was analysed and the thermal expansion co-efficient was calculated for both the quasi-harmonic and molecular Dynamics. It can be seen, as low temperatures are approached, it is best to use the quasi-harmonic approximation over molecular dynamics because it takes into account that a crystal will have a zero point energy. A further investigation could be to explore how the values of the Helmholtz free energy, lattice volume and thermal expansion co-efficient differ with group 2 oxides using GULP.

References

- ↑ A. P. Sutton; Electronic Structure of Materials; Oxford University Press; Oxford; 1995; p 42

- ↑ R. Hoffmann; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl.; 1987; Vol. 26; Issue 9.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 http://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/harrison/Teaching/Thermal_Expansion/

- ↑ G.P. Srivastava; The Physics of Phonons; CRC Press; United States; 1990; pp 113-114

- ↑ P. Atkins, J. de Paula; Atkins’ Physical Chemistry; Oxford University Press; Oxford; Ninth Edition; 2009; pp 48-52, 114-115.

- ↑ K.S. Singh, R.S. Chauhan; Elsevier Physics B; 2002; pp 74-81; doi: 10.1016/S0921-4526(01)01095-X

- ↑ D. T. Haworth; J. Chem. Edu.; 1967, Vol. 44; Issue 6; p 353; doi: 10.1021/ed044p353

- ↑ B. Kumar, S. J. Rodrigues, L. G. Scanlon; J. Electrochem. Soc.; 2001; Vol. 148; Issue 10; pp A1191-A1195; doi: 10.1149/1.1403729