Rep:Mod:Yhl211

The Hydrogenation of Cyclopentadiene Dimer

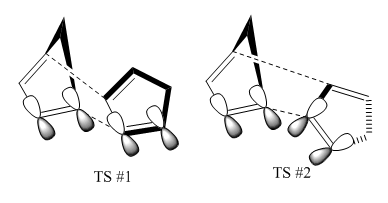

Cyclopentadiene dimerises to form the predominant endo dimer 2 rather than the exo dimer 1.[1] The [4+2] Diels-Alder cycloaddition reaction is kinetically controlled as the exo dimer 1 was modelled using the MMFF94 force field to have a lower energy of 55.4 kcal/mol (c.f 58.2 kcal/mol for endo dimer) and therefore should be the dominant product in thermodynamic sense. The stability of the endo product is accounted for in the transition state. As depicted in Figure 2, one of the rings will bend upwards for the formation of the new bonds and the other ring can approach from below in two ways; facing up or down which then produces the exo and endo dimer respectively. The former ring could also bend downwards following an attack on the top face but it leads to the mirror image of the product which is indistinguishable. The transition state of dimer 4 has the correct orientation for the overlap of p-orbitals on both rings which stabilize the transition leading to the kinetic endo product.

| Energies of dimers obtained | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters (kcal/mol) | Dimer 1 | Dimer 2 | |||

| Stretch | 3.54453 | 3.46690 | |||

| Bend | 30.77951 | 33.19325 | |||

| Stretch-Bend | -2.04106 | -2.08208 | |||

| Torsion | -2.73308 | -2.94944 | |||

| Out-of-plane Bending | 0.01376 | 0.02210 | |||

| Van der Waals | 12.79694 | 12.35592 | |||

| Electrostatic Energy | 13.01266 | 14.18409 | |||

| Total Energy | 55.3753 | 58.1984 | |||

The catalytic hydrogenation of the endo dimer will initially produce a dihydro derivative and then to the tetrahydro product.[2] Dihydro derivative 4 is thermodynamically more stable than isomer 3 as modelled by the MMFF94 force field. The heat of hydrogenation is exothermic as product 4 has a lower energy than reactant 2 and is reasoned by the higher heat given off with the formation of 2 C-H bonds (cf. 98 x2 kcal/mol)[3] as compared to the energy used to cleave a C=C bond (cf. 146 kcal/mol). The heat of hydrogenation of the double bond of the norbornene ring (32.2 kcal/mol) is higher than that of the five membered ring (26.2 kcal/mol) concluding that the former double bond is more reactive and is hydrogenated first.

The individual parameters of the dimers have a relatively similar value except that of bend and torsion. Dimers 1, 2 and 3 have a higher bend energy than 4 as the former has a double bond in the norbornene ring. The p-orbitals involved in the formation of the double bond repels the bridge head when it is stressed resulting in a higher energy.[4] This also accounts for the higher stability of dimer 4 as compared to 3 as the former is not subjected to such repulsion as the norbornene ring is saturated.

| MMFF94 Force Field | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters (kcal/mol) | Dimer 3 | Dimer 4 | |||

| Stretch | 3.30723 | 2.82266 | |||

| Bend | 30.86737 | 24.68682 | |||

| Stretch-Bend | -1.92640 | -1.65695 | |||

| Torsion | 0.06342 | -0.37605 | |||

| Out-of-plane Bending | 0.01530 | 0.00028 | |||

| Van der Waals | 13.27491 | 10.63375 | |||

| Electrostatic Energy | 5.12099 | 5.14704 | |||

| Total Energy | 50.7259 | 41.262 | |||

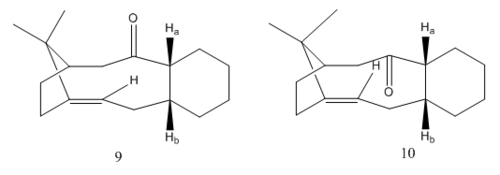

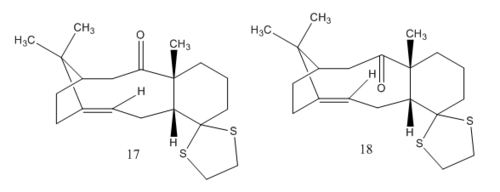

In the synthesis of Taxol, one of the key intermediates (17 and 18) can exist as atropisomers as the conformation of the molecule is locked by the ring. To understand the relative stability of the isomers, simpler derivatives of the intermediates (9 and 10) are modelled using the MMFF94 force field to characterise the conformation of certain bonds that results in overall stabilization of the molecule.

| Energies of dimers obtained using the MMFF94 force field | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimer Number | Energy (kcal/mol) | Comments | |||

| Dimer 9 | 70.5347 | Ha and Hb are cis and are pointing out of the plane

Cyclohexane ring is in chair conformation | |||

| Dimer 9 | 63.2595 | Ha and Hb are cis and are pointing into of the plane

Cyclohexane ring is in chair conformation | |||

| Dimer 10 | 60.6022 | Ha and Hb are cis and are pointing into of the plane

Cyclohexane ring is in chair conformation | |||

| Dimer 10 | 74.3637 | Ha and Hb are cis and are pointing into of the plane

Cyclohexane ring is in twist boat conformation (sterically restricted) | |||

The molecule is more stable when the hydrogens on the carbons fusing the rings (Ha and Hb) are pointing in the opposite direction to the carbonyl which minimize steric clash due to the large oxygen atom. Assuming that the rest of the molecule is the same, isomer 10 (60.6022 kcal/mol) is more stable than 9 (63.2595 kcal/mol) as the hydrogens are pointing upwards in both isomers and the molecule is therefore most stable is when the carbonyl is pointing downwards.

To identify the most stable structure of the molecule, individual atoms have to be in the configuration that contributes the least energy to the molecule.

The cyclohexane ring can interconvert between the chair, boar and twist-boat conformers due to its low energy barrier but it is most stable in the chair conformation. The chair conformation is when the carbons are staggered (C2, C3, C5, C6 lie on the same plane while C1 and C6 lies above and below the plane respectively) to minimize angle and torsional strain. This conformation is very stable as it has a carbon bond angle of 110.9° (c.f ideal sp3 hybridized bond angle=109.5°) and is perfectly staggered with no torsional strain. [5]

| Effect of the conformation of the cyclohexane ring on the energy of dimer 9 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ring conformation | Energy (kcal/mol) | Comments | |||

| Twist Chair | 77.9052 | Dimer 9 is ~7 kcal/mol more stable in the chair conformation than the twist chair.

Agrees with the literature value of 5-6 kcal/mol [5] | |||

| Chair | 70.5347 | ||||

When the conformation of the molecule is fixed, the structure with the lowest energy will be when the carbon distal (green) to the oxygen is pointing in the opposite direction to minimize repulsion due to the large carbonyl atom.

Therefore, the lowest conformation of the isomer is when the cyclohexane ring is in a chair conformation, carbon distal to the carbonyl is pointing in the opposite direction and when the hydrogen on the carbon fusing the largest ring and the cyclohexane ring are cis and opposite in direction to the carbonyl.

Isomer 18 |

Upon further minimization, derivatives of the intermediates which had a lower energy were modelled when the Ha and Hb are trans to each other with the Ha pointing in the opposite direction to the carbonyl. A derivative for isomer 9 was modelled to have an energy of 60.65 kcal/mol and that of isomer 10 was 65.68 kcal/mol. This derivative of isomer 9 is useful as it is has a lower energy than the other isomers of 9 and could be useful in reactions that require the stereochemistry of the carbonyl to be pointing upwards. It is also worth noting that when carbonyl up and hydrogen are pointing upwards, that conformation is ~4kcal/mol lower than when all carbonyl and hydrogen are pointing downwards. This is due to the repulsion from the cyclopentene ring which is folded downwards and it subjected to more repulsion when the carbonyl and hydrogen are pointing in the same direction.

The alkene in the intermediates react unusually slowly as it is a hyperstable alkene. According to the IUPAC definition of Bredt's rule,

"A double bond cannot be placed with one terminus at the bridgehead of a bridged ring system unless the rings are large enough to accommodate the double bond without excessive strain."

For a bridgehead alkene of a small system, the torsional forces in the double bond are high which causes the non-hybridized pz orbital to be twisted and misaligned. The poor overlap of the p orbitals causes the formation of a double bond to be unfavourable. However, for a system with a larger cyclic ring, bridgehead alkene can still be formed provided the double bond is trans to the larger ring as that allows a good overlap of the p orbitals.[4]

Intermediates 17 and 18 were modelled as above to obtain the lowest energy conformation together with the free energies, ΔG that were calculated from the entropy and zero-point energy correction using Gaussian:

| Intermediate 17 [6] | Intermediate 18 [7] | |

|---|---|---|

| Gibbs Free Energy, ΔG (J/mol) | -4335885761 | -4335911545 |

| MMFF94 Minimization Energy (kcal/mol) | 104.75 | 100.50 |

The difference in free energies of the two isomers is approximately 26 kJ/mol and the equilibrium constant, K is found to be 2.76x10-5 for the isomerization of 18 to 17. This indicates that the isomerization of 18 to 17 is totally unfavoured which corresponds with the previous calculation stating that isomer 18 is the preferred conformer as it has a more negative free energy value (c.f 100.50 kcal/mol for isomer 18 vs 104.75 kcal/mol for isomer 17).

NMR spectra of isomer 18 was simulated using GaussView and compared to literature values.

| 13C (benzene) NMR of intermediate 18 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literature value/ppm [8] | Simulated value/ppm [7] | ||||

| 211.49 | 211.06 | ||||

| 148.72 | 147.94 | ||||

| 120.90 | 120.03 | ||||

| 60.53 | 60.46 | ||||

| 51.30 | 54.77 | ||||

| 50.94 | 53.94 | ||||

| 40.82 | 41.89 | ||||

| 38.73 | 41.73 | ||||

| 36.78 | 38.52 | ||||

| 35.47 | 34.05 | ||||

| 30.84 | 28.09 | ||||

| 25.56 | 26.45 | ||||

| 25.35 | 24.40 | ||||

| 22.21 | 22.61 | ||||

| 21.39 | 21.87 | ||||

| Anomalies | |||||

| 74.61 | 93.63 | ||||

| 45.53 | 49.53 | ||||

| 43.28 | 49.15 | ||||

| 19.83 | 46.67 | ||||

| 1H (benzene) NMR of intermediate 18 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literature value/ppm [8] | Simulated value/ppm [7] | Notes | |||

| 5.21 | 5.95 | 1H, alkenic protons | |||

| 3.00-2.70 | 3.18-2.77 | 3H, 1H of which is adjacent to carbonyl (different environment as the other carbonyl H)

Degenerate peaks, unable to assign individual peaks | |||

| 2.70-2.35 | 2.67-2.39 | 4H, H in various environments | |||

| 1.58 | 1.56 | 1H, H adjacent to carbonyl (different environment as the other carbonyl H) | |||

The simulated 13C spectra correlate well with the literature except for some anomalies listed in the table above. The anomalies require a spin-orbit coupling correction due to the heavy sulfur atom. Insufficient data is provided in the spectral data of the literature as specific carbons were not addressed and shifts could only be assigned relative to the magnitude of the shifts which may not be accurate. Shifts for certain carbons not adjacent to sulfur could not be assigned due to lack of data. The 1H shifts that could be assigned were hydrogens adjacent to functional groups as they are well defined. The simulated 1H spectral data shows little correlation to that of the literature as it was dated to 24 years ago when spectroscopic techniques were not as advanced which resulted in incorrect data reported. Simulating spectral data using computational methods produce better and more accurate results.

Analysis of the properties of trans-stilbene and 1,2-dihydronaphthalene epoxides

Crystal Structure of the asymmetric epoxidation catalyst

Shi Catalyst

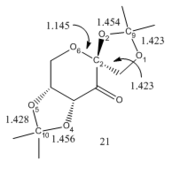

A crystal structure of the Shis fructose pre-catalyst was modelled using ConQuest and Mercury and the anomeric centres were studied. As observed in labelled diagram of the pre-catalyst, Figure 5, O6-C2 bond lengths are shorter than the other C-O bonds as it is part of a 6-membered ring in its stable chair conformation. The O2-C9 bond is anomalously longer than its counterparts as it is subjected to the stabilizing anomeric effect. The lone pair on O1 has the correct orientation to donate electron density into the anti periplanar σ* (O2-C9) bond which results in a weaker and longer bond. The same effect is observed on the O4-C10 bond subjected to donation from the lonepair on O5. The other C-O bond lengths are similar to a typical C-O bond length (c.f 1.43 Å) and is therefore unaffected by the anomeric effect as they do not have the correct orbital overlap.

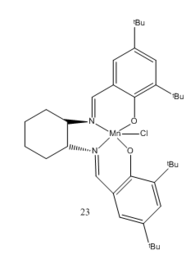

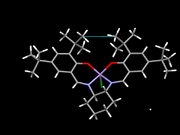

Jacobsen Catalyst

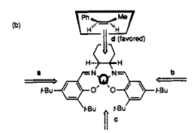

Using Mercury to compute the crystal structure of the Jacobsen pre-catalyst, both the tert-butyl groups substituted ortho to the salen-oxygen is at a distance of 3.745 Å which is 0.345 Å longer than the sum of the van der Waals radii of the two carbon atoms. Based on the Lennard-Jones potential, the maximum attraction occurs at the distance corresponding to approximately twice of the van der Waals radius [10]. At shorter distances, the interaction is repulsive which is the reason tert-butyl is a good substituent for the catalyst as a larger group would repel each other while a smaller group would have a lesser attraction.

When a tert-butyl group is substituted para to the salen-oxygen, a side-on attack is unfavourable due to steric clash. Approach from the ortho-tBu face (approach c) is also hindered as it possesses a favourable attractive interaction and is unlikely to disrupt its geometry as it is distance dependant. [9] The side syn to the cyclohexane ring (approach b) is more disfavoured due to the additional steric hindrance from the ring and the bulky tert-butyl group. Therefore, the most favourable mode of approach is the top face which makes the Jacobsen catalyst an excellent catalyst for the cis-selective epoxidation of alkenes.[9]

Simulated NMR spectra of synthesised alkenes

|

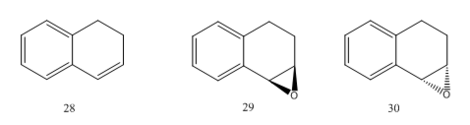

Using the asymmetric Shi and Jacobsen catalysts above to epoxidate two different alkenes 25 and 28, 4 stereospecific epoxides are obtained. The two chosen alkenes trans-stilbene, 26 and 1,2-dihydronaphthalene, 28 were modelled using Gaussian to obtain predicted NMR specta in attempt to understand the mechanism of epoxidation using the two catalysts.

| 13C (CDCl3) NMR of epoxide 26 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literature chemical shift/ppm [11] | Simulated chemical shift/ppm [12] | Integration & atom environment | |||

| 134.8 | 131.3 | 2C, C-CO | |||

| 128.7, 127.6, 127.3 | 122.9, 122.6, 122.3, 122.1 | 10C, ArCH | |||

| 60.2 | 62.0 | 2C, CHO | |||

| 1H (CDCl3) NMR of epoxide 26 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literature chemical shift/ppm [11] | Simulated chemical shift/ppm [12] | Integration & atom environment | |||

| 7.11-7.00 | 7.25-7.49 | 10H, ArH | |||

| 4.24 | 4.30, 4.31 | 2H, CHO | |||

| 13C (CDCl3) NMR of epoxide 27 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literature chemical shift/ppm [11] | Simulated chemical shift/ppm [13] | Integration & atom environment | |||

| 137.6 | 134.1 | 2C, C-CO | |||

| 129.0, 128.8, 126.2 | 124.2, 123.5, 123.2, 118.3 | 10C, ArCH | |||

| 63.3 | 66.4 | 2C, CHO | |||

| 1H (CDCl3) NMR of epoxide 27 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literature chemical shift/ppm [11] | Simulated chemical shift/ppm [13] | Integration & atom environment | |||

| 7.57-7.34 | 7.57-7.45 | 10H, ArH | |||

| 3.91 | 3.54 | 2H, CHO | |||

| 13C (CDCl3) NMR of epoxide 29 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literature chemical shift/ppm [14] | Simulated chemical shift/ppm [15] | Integration & atom environment | |||

| 136.7 | 133.8 | 2C | |||

| 132.6 | 130.4 | 1C | |||

| 129.6 | 125.6 | 1C | |||

| 128.5 | 123.8 | 1C | |||

| 128.4 | 123.4 | 1C | |||

| 126.1 | 121.4 | 1C | |||

| 55.1 | 56.4 | 1C | |||

| 52.8 | 54.8 | 1C | |||

| 24.4 | 28.0 | 1C | |||

| 21.8 | 24.9 | 1C | |||

| 1H (CDCl3) NMR of epoxide 29 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literature chemical shift/ppm [14] | Simulated chemical shift/ppm [15] | Integration & atom environment | |||

| 7.27 | 7.49 | 1H | |||

| 7.11 | 7.40, 7.37 | 2H | |||

| 6.97 | 7.19 | 1H | |||

| 3.72 | 3.61 | 1H | |||

| 3.61 | 3.57 | 1H | |||

| 2.67 | 2.88 | 1H | |||

| 2.43 | 2.27 | 1H | |||

| 2.29 | 2.22 | 1H | |||

| 1.64 | 1.56 | 1H | |||

| 13C (CDCl3) NMR of epoxide 30 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literature chemical shift/ppm [16] | Simulated chemical shift/ppm [17] | Integration & atom environment | |||

| 137.1 | 135.4 | 1C | |||

| 132.9 | 130.4 | 1C | |||

| 129.9 | 126.7 | 1C | |||

| 128.8 | 123.8 | 1C | |||

| 128.8 | 123.5 | 1C | |||

| 126.5 | 121.7 | 1C | |||

| 55.5 | 52.8 | 1C | |||

| 55.2 | 52.2 | 1C | |||

| 24.8 | 30.2 | 1C | |||

| 22.2 | 29.1 | 1C | |||

| 1H (CDCl3) NMR of epoxide 30 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literature chemical shift/ppm [14] | Simulated chemical shift/ppm [17] | Integration & atom environment | |||

| 7.33 | 7.62 | 1H | |||

| 7.17 | 7.39 | 2H | |||

| 7.01 | 7.25 | 1H | |||

| 3.78 | 3.56 | 1H | |||

| 3.65 | 3.48 | 1H | |||

| 2.67 | 2.95 | 1H | |||

| 2.45 | 2.26 | 1H | |||

| 2.33 | 2.21 | 1H | |||

| 1.67 | 1.87 | 1H | |||

Assigning the absolute configuration of the product

In attempt to assign the absolute configuration of the synthesised alkenes, the optical rotation was calculated using Gaussian and then compared to the literature values using Reaxys. The optical rotation at wavelengths 365 nm and 589 nm was calculated but the literature values were unavailable at the wavelength of 365 nm. The literature values for cis-stilbene were inaccurate as it dates to 1979 and that of (R,S)-dihydronaphthalene oxide dates back to 1996. Computing the results using Gaussian provide a more accurate result.

| Optical rotations of synthesised alkenes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkenes | Wavelength (nm) | Literature optical rotation (deg) | Simulated optical rotation (deg) | ||

| cis-stilbene [18] [19] | 365 | -0.54 | - | ||

| 589 | 0.22 | 87.1 | |||

| trans-stilbene [20] [21] | 365 | 1253.76 | - | ||

| 589 | 297.96 | 250.8 | |||

| (1R,2S)-1,2-epoxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalene [22] [7] | 365 | -209.46 | - | ||

| 589 | -35.87 | 129 | |||

| (1S,2R)-1,2-epoxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalene [23] [13] | 365 | -522.14 | - | ||

| 589 | -155.82 | -144.9 | |||

Computing the properties of the transition state of β-methyl styrene

To identify the lowest energy transition state, total energy for each system as corrected for entropy and zero-point thermal energies were calculated using Gaussian whereby the most stable transition state is (R,R) 2 and (S,S) 2. The ΔG value was calculated to be and therefore K=0.02139. Using the formula for enantiomeric excess, the ee was found to be 95.8% excess of (S,S) 2 (in good agreement with literature value of 95.5%), concluding that the (S,S) 2 transition state is most stable. For the formation of the (S,S) epoxide, the Re-Si face is reacted in which Re being the carbon adjacent to the phenyl ring and Si being the carbon further away. The axial carbonyl is transferred in the epoxidation of the olefin as it is less hindered. As observed in the transition state, the phenyl ring is orientated in an exo fashion with respect to the fructose.

Subjecting the same mode of calculation on the transition states for the Jacobsen epoxidation of β-methyl styrene, the two most stable diastereomeric transition states is (S,R) 1 & (R,S) 2 for the cis isomer and (S,S) 2 & (R,R) 1 for the trans isomer. Using the same formula, the enantiomeric excess of (R,S) 2 is calculated to be 93.3% for cis β-methyl styrene and 97.1% ee for (R,R) 1 for the trans β-methyl styrene.

As observed in the transition state, the catalyst orientates itself in an endo fashion to the olefin phenyl ring.

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Using vibrational circular dichroism (VCD) is a more accurate technique to assign the absolute configuration of molecules but this requires comparison to an experimental spectra. The VCD technology is relatively new and experimental spectra are unavailable for the synthesised alkene at the time of writing but it is an excellent technique that will be used in the future.

Non-covalent interactions in the active-site of the transition state

To study the non-covalent-interaction of transition state for the reaction between the Shi catalyst and trans-stilbene, the electron density of the system was computed using GaussView. This computes the regions with low electron density and reduced density gradient to reveal the non covalent interactions. As observed in the model, the alkene undergoes epoxidation in a spiro transition state with favourable NCI interactions (green) on the face of the molecule. The spiro transition state is preferred due to the orbital overlap between the π* orbital of the alkene and the oxygen lone pair which is absent in the planar mode of attack.[40] When the alkene is trisubstituted, the planar transition state is favoured due to steric effects overriding the favourable interaction.

The multi-coloured ring indicates the formation of a bond but is normally ignored in the NCI analysis. Many NCI attractive interactions are observed between the catalyst and the alkene which includes hydrogen bonds, dispersion forces and electrostatic attraction. The transition state is stabilized by attractive interaction rationalised to be hydrogen bonding between electronegative oxygen atoms and hydrogens on the alkene. Attractive interactions were also observed between the O atom and the benzene due to the delocalized electron cloud above the planar ring. A small mildly repulsive area is observed between the benzene ring which indicates the electrostatic repulsion between the delocalized electrons proving the known fact that electrons are delocalized in an aromatic ring.

Electronic topology (QTAIM) in the active-site of the transition state

Bond critical point (BCP) is a region along a bond where the electron density curvature is a minimum in the bonding direction. The transition state as before was modelled using Avogadro2 to obtain a framework of electron density(QTAIM). For a heteroatom bond i.e C-O bond, the electron density around the oxygen is higher as it is more electronegative which results in the minimum in electron density being shifted towards the carbon atom. BCPs also represent the strength of the ionic character in a covalent bond. The stronger the ionic character in a covalent bond, the further the BCP deviates from the ideal centre. As observed in benzene, the BCP is in the middle of the C-C bond as it is a covalent bond between two atoms that do not differ in electronegativity therefore electrons are shared equally between the two atoms.[41]

Weak non covalent BCPs are observed between O and H atoms which suggest the stabilizing hydrogen bonding. This is supported by the non-covalent interaction analysis explained before as there are electron densities being shared between the two atoms. Interactions are also observed from the oxygen to the BCP between a C-C bond which corresponds to the findings above. Also in the model, there is only one BCP from the dioxirane oxygen to the olefin carbon which suggests that the mechanism of reaction is not concerted.

Suggestions for new candidates for investigation

Cyclohexene oxide is an interesting molecule as it there will be multiple conformers for the 6 membered ring. The most stable transition state has to be modelled as the epoxide can orientate itself away or towards the ring with respect to the individual conformation of the ring using techniques already encountered in this assignment. The effect of strain energies of the different conformation can be studied in more depth and studies can be conducted on the effect of the oxygen substituent which may or may not change the structure of the ring.

References

- ↑ P. Caramella , P. Quadrelli , L. Toma, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2002, 124, 1131 DOI:10.1021/ja016622h

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Polymer Science and TechnologyJohn Wiley & Sons, 2007, 5, 765

- ↑ Z. Tian , L. Lis , S. R. Kass , J. Org. Chem., 2013, 78, 12653 DOI:10.1021/jo402263v

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 G. K. KhatriTata McGraw-Hill Education, 1998, 3

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 M. Squillacote , R. S. Sheridan , O. L. Chapman , F. A. L. Anet, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1975, 97, 3246 DOI:10.1021/ja00844a068

- ↑ Y. Lee , Gaussian Job Archive C20H20O1S2, 2014 DOI:10042/27373

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Y. Lee , Gaussian Job Archive C20H20O1S2, 2014 DOI:10042/27372 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "yhl6" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 8.0 8.1 L. A. Paquette , N. A. Pegg , D. Toops , G. D. Maynard , R. D. Rogers, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1990, 112, 283 DOI:10.1021/ja00157a043

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 E. N. Jacobsen , W. Zhang , A. R. Muci , J. R. Ecker , L. Deng, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1991, 113, 7064 DOI:10.1021/ja00018a068

- ↑ M. Mantina , A. C. Chamberlin , R. Valero , C. J. Cramer, D. G. Truhlar , J. Phys. Chem. A, 2009, 113, 5812 DOI:10.1021/jp8111556

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 M. W. C. Robinson, . A. M. Davies, . R. Buckle, I. Mabbett, . . S. H. Taylor, . . A. E. G. , Org. Biomol. Chem., 2009,7, 2559 DOI:10.1039/B900719A

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Y. Lee , Gaussian Job Archive C14H12O12, 2014 DOI:10042/27374

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Y. Lee , Gaussian Job Archive C14H12O1, 2014 DOI:10042/27375 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "yhl8" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 US Pat.US2011040092A1., 2011

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Y. Lee , Gaussian Job Archive C10H10O1, 2014 DOI:10042/27377

- ↑ Avecia Pharmaceuticals LimitedWO2005056543A2, 2005

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Y. Lee , Gaussian Job Archive C10H10O1, 2014 DOI:10042/27376

- ↑ Y. Lee , Gaussian Job Archive C14H12O1, 2014 DOI:10042/27378

- ↑ Y. Lee , Gaussian Job Archive C14H12O1, 2014 DOI:10042/27363

- ↑ Y. Lee , Gaussian Job Archive C14H12O1, 2014 DOI:10042/27380

- ↑ Y. Lee , Gaussian Job Archive C14H12O1, 2014 DOI:10042/27379

- ↑ Y. Lee , Gaussian Job Archive C10H10O1, 2014 DOI:10042/27364

- ↑ Y. Lee , Gaussian Job Archive C10H10O1, 2014 DOI:27361

- ↑ Rzepa, Henry S. (2013): Gaussian Job Archive for C21H28O7. figshare. http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.738028

- ↑ Rzepa, Henry S. (2013): Gaussian Job Archive for C21H28O7. figshare. http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.749615

- ↑ Rzepa, Henry S. (2013): Gaussian Job Archive for C21H28O7. figshare. http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.738036

- ↑ Rzepa, Henry S. (2013): Gaussian Job Archive for C21H28O7. figshare. http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.738037

- ↑ Rzepa, Henry S. (2013): Gaussian Job Archive for C21H28O7. figshare. http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.738038

- ↑ Rzepa, Henry S. (2013): Gaussian Job Archive for C21H28O7. figshare. http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.739115

- ↑ Rzepa, Henry S. (2013): Gaussian Job Archive for C21H28O7. figshare. http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.739116

- ↑ Rzepa, Henry S. (2013): Gaussian Job Archive for C21H28O7. figshare. http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.739117

- ↑ Rzepa, Henry S. (2013): Gaussian Job Archive for C37H46ClMnN2O3. figshare. http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.740436

- ↑ Rzepa, Henry S. (2013): Gaussian Job Archive for C37H46ClMnN2O3. figshare. http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.783851

- ↑ Rzepa, Henry S. (2013): Gaussian Job Archive for C37H46ClMnN2O3. figshare. http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.740437

- ↑ Rzepa, Henry S. (2013): Gaussian Job Archive for C37H46ClMnN2O3. figshare. http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.783898

- ↑ Rzepa, Henry S. (2013): Gaussian Job Archive for C37H46ClMnN2O3 DOI:10042/25945

- ↑ Rzepa, Henry S. (2013): Gaussian Job Archive for C37H46ClMnN2O3. figshare. http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.856650

- ↑ Rzepa, Henry S. (2013): Gaussian Job Archive for C37H46ClMnN2O3. figshare. http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.856649

- ↑ Rzepa, Henry S. (2013): Gaussian Job Archive for C37H46ClMnN2O3. figshare. http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.856651

- ↑ Z. Wang, Y. Tu, M. Frohn, J. Zhang, Y. Shi, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1997, 119, 11235 DOI:10.1021/ja972272g

- ↑ J. R. Lane, J. Contreras-García, J. Piquemal, B. J. Miller, H. G. Kjaergaard, J. Chem. Theory Comput., 2013, 9, 3266