Rep:Mod:Y3S1CLKB10

Conformational analysis using Molecular Mechanics

Cyclopentadiene dimer and derivatives

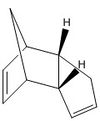

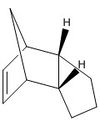

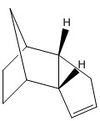

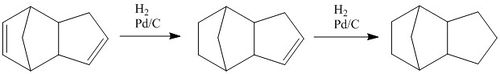

Avogadro programme used to optimise geometries of cyclopentatiene dimers and the hydrogenated derivatives. These structures are shown in the table below:

| Molecule# | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure |  |

|

|

|

| Jmol |

| Molecule | Total Energy | Total Bond stretching Energy | Total Angle Bending Energy | Total Torsional Energy | Total van der Waals Energy | Total Electrostatic Energy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 55.44940 | 3.55010 | 30.85660 | -2.84916 | 12.90156 | 13.01449 |

| 2. | 58.19074 | 3.46712 | 33.19251 | -2.94980 | 12.35633 | 14.18461 |

| 3. | 50.50437 | 3.28547 | 31.32664 | -0.84281 | 13.65445 | 5.11960 |

| 4. | 41.26391 | 2.81956 | 24.70466 | -0.35761 | 10.60502 | 5.14729 |

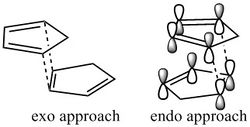

The optimisations described above were carried out using the MMFF94s Force Field, and the energies displayed in Table 1 were computed in Avogadro. The comparison of total energies shows the exo dimerisation product is more stable and thus expected as the thermodynamic product. However, literature reports that the endo-adduct predominates[1] and hence the [π2s+π4s] cycloaddition must proceed under kinetic control. The exo dimer is reported as favourable only under equilibrating conditions. The difference in approach of the dienophile for production of the regio-adducts is presented to the right. The selectivity of the endo-adduct can be attributed to the so called "secondary orbital interactions", displayed in the figure to the right, as well as steric factors. At higher temperatures, the secondary orbital effect is observed less, and so the preference is less significant; hence the exo-adduct will begin to predominate when T>~400K.

The tetrahydro derivative of dicyclopentadiene is generated according to the catalytic reaction scheme[2] presented in the figure to the left. The first step is shown as the hydrogenation of the double bond in the norborene part of the ring. The energies for molecules 3 and 4 in the table above suggest that the generation of dihydro derivative 4 is thermodynamically more favorable. The contributing energies show that hydrogenation of the norborene double bond provides twice the lowering of energy that would result from reduction of the cyclopentadiene ring. This is primarily observed in the bond angle energies, suggesting that reduction of the norborene-alkene provides substantial relief in angle strain (measurement of the optimised structure shows that the non-bridging C-C-C bond angle in the ring is 107°, a large deviation from the typical 120° angle of an sp2 carbon). Additionally, the van der Waals energy is seen to rise on reduction of the cyclopentadiene-alkene first, however this effect contributes less to the overall energy than the angle bending energy.

An Intermediate in the Synthesis of Taxol

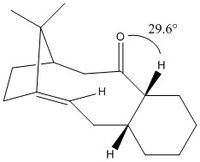

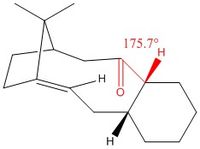

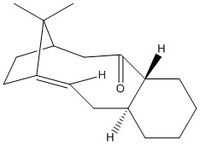

A key intermediate in the synthesis of taxol exhibits atropisomerism, whereby restricted rotation about a C-C bond leads to two different conformers which can be isolated. The structures 9 and 10 were optimised in Avogadro, and conformer 11 was then reached after further manipulation and optimisation of the geometry, as described below.

| Molecule # | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure |  |

|

|

| Jmol |

The optimisations described above were carried out using the MMFF94s Force Field, and the following energies were computed in Avogadro. It is observed in Table 2 that 10, where the carbonyl is pointing down, has a lower energy, and this is mainly due to a decrease in angle strain since the carbonyl and hydrogen on the neighboring tertiary carbon are antiperiplanar in 10. However, the cyclohexane ring occupies a chair conformation in 9 and the more energetic twist-boat conformation in 10. Therefore in order to locate the most stable conformation, the molecule was manually edited to include both the antiperiplanar oxygen-hydrogen dihedral angle as well as the chair conformation of the ring. This resulted in the lower energy conformation of the entire molecule (11).

| Molecule # | Total Energy | Total Bond stretching Energy | Total Angle Bending Energy | Total Torsional Energy | Total van der Waals Energy | Total Electrostatic Energy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9. | 75.45604 | 8.24031 | 27.68871 | 1.88366 | 36.77272 | 0.39179 |

| 10. | 68.44901 | 7.56714 | 23.48811 | 1.00175 | 34.92437 | 0.89597 |

| 11. | 62.06608 | 7.31944 | 21.69545 | 0.03160 | 34.92505 | 0.89985 |

Spectroscopic Simulation using Quantum Mechanics

Another Intermediate for Taxol

| Molecule # | 18 |

|---|---|

| Structure |

|

| Jmol |

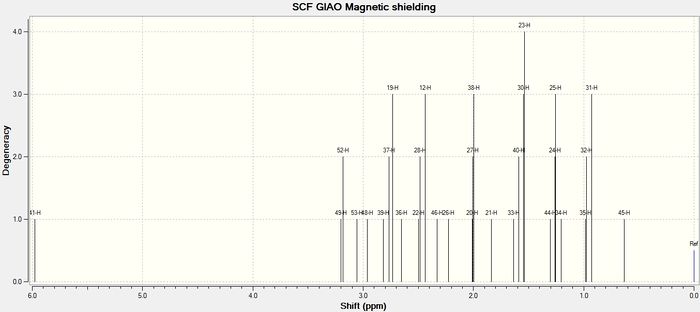

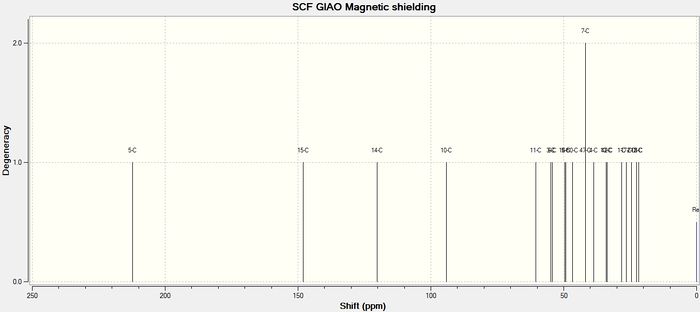

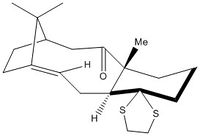

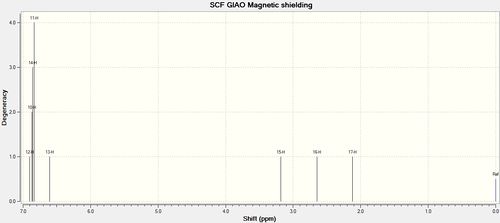

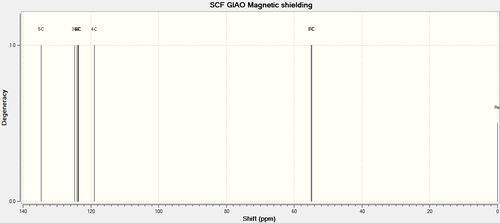

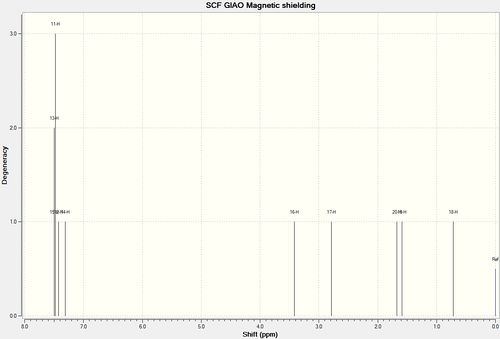

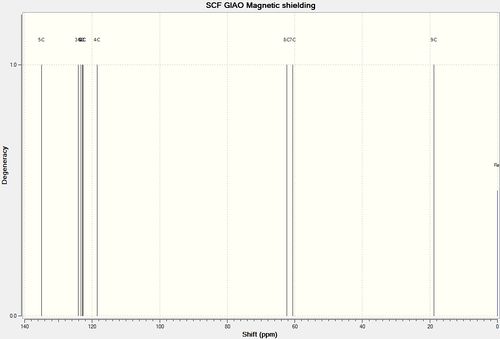

Molecule 18, shown to the right, was built in Avogadro and the geometry optimised under the MMFF94s force field. Gaussian extension was then used to submit a DFT B3LYP 6-31G(d,p) level calculation to the HPC DOI:10042/26635 , for optimisation, frequency analysis and NMR spectrum generation. The input structure was drawn to be similar to molecule 11 shown above (i.e. with the carbonyl pointing down and the 6-membered ring in a chair conformation), as this resulted in the lowest energy. The output file was viewed in GaussView and the computed NMR spectra could then be inspected and compared to the spectroscopic data found in literature;[3] this analysis is presented in the tables below. The comparison will be useful in assessing the strength of the computational method, since a good match to experimental data suggests an accurate optimisation. It should be noted that in such calculations, fluctuations due to bond rotation is not accounted for; instead the calculation is carried out on a 'snapshop' of the molecule and hence equivalent protons are treated separately.

Agreement between the computed proton-NMR chemical shifts and those experimentally determined is strong, deviating by <1ppm. The largest deviation is associated with the most deshielded proton (CH=C-) for which Δδ=0.77ppm. In contrast, carbon NMR exhibits larger deviations from literature chemical shifts and overall the calculated spectrum is shifted downfield. Deviations are found to be in the range 0.5ppm<Δδ<3.5ppm, however in one instance a discrepancy of 20ppm is observed. This may be explained due to the presence of sulphur (this shift is for the carbon harbouring the dithiane group). Being a heavier atom, sulphur can lead to errors due to spin-orbit coupling, and the calculation will involve a correction for this, however it is unlikely that this would account for such a high deviation. A more thorough discussion could be achieved if couplings were also calculated, had time not been a factor. This could be done by using the "NMR(spinspin,mixed)" keyword in the calculation file.

Hyperstable olefins

| Molecule # | 9 | 11 | 10 | 12 | 18 | 19 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Energy | 75.45604 | 83.00929 | 68.44901 | 81.41858 | 100.49234 | 117.86570 | ||

| Bond Stretching Energy | 8.24031 | 8.12931 | 7.56714 | 7.23625 | 15.02246 | 14.27306 | ||

| Angle Bending Energy | 27.68871 | 27.86809 | 23.48811 | 27.15892 | 30.81964 | 37.23325 | ||

| Torsional Energy | 1.88366 | 9.70992 | 1.00175 | 11.46407 | 9.69570 | 18.96059 | ||

| Van der Waal Energy | 36.77272 | 37.15573 | 34.92437 | 35.09445 | 49.45865 | 49.87105 | ||

| Electrostatic Energy | 0.39179 | 0.00000 | 0.89597 | 0.00000 | -6.05684 | -4.01976 |

On initial inspection, molecules with the structure of 9, 10 and 18 might be expected to be very reactive towards hydrogenation of the alkene; bond angles in the carbon framework at the sp2 centers is distorted away from prefered 120° (trigonal planar) and therefore functionalisation would relieve the strain, generating an more energetically stable alkane counterpart.

However an analysis of the hydrogenated species (11, 12, and 19 respectively) shows that in fact the energy is higher than that of the alkene and so the parent alkenes may be called 'hyperstable olefins'. These details are displayed in the following table. The energies (in kcal/mol) were computed using Avogadro and the MMFF94s force field.

Hydrogenation of the alkene species leads to significant increases in angle bending and torsional energies, hence the reactivity is very low. Literature states that the "major reason for the relief of energy...is the change of hybridization at the bridgehead position."[4] For example, when the alkene 9 is hydrogenated the bond angle between the former double bond and the bridgehead changes from 133° to 123.3°, which is also 13° away from the typical angle of 109.5°.

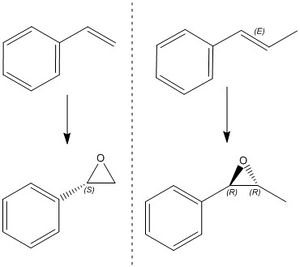

Analysis of synthesised alkene epoxides

The Catalysts

The 'Conquest' and 'Mercury' programmes were used respectively to locate and visualise the structures of the Shi and Jacobsen pre-catalysts. Their rotatable jmol images are presented below:

| Jacobsen Catalyst (TOVNIB01) | Shi Catalyst (NELQEA01) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| The main feature to be examined in the case of Jacobsen's catalyst are the close distances between hydrogens on adjacent tert-butyl groups. Various distances have been highlighted on the image above. The sum of the van der Waals radius of 2 hydrogens is 240pm, and distances shorter than this result in respulsive interactions. Above this length however attractive forces are observed, as is the case for this molecule. The tert-butyl groups experience attractive interactions and are essentially pulled closer together, making the structure distort from planar and into a more 'curved' shape. Thus one side of the molecule is less hindered to attack, and allows for a favoured approach of the alkene to this side. | There is one anomeric center identified in the Shi catalyst, a fructose derived structure with acetal protecting groups. The anomeric effect can be observed by the axial positioning of the C2 hetero-substituent. The C-O bond lengths at this anomeric center can be observed and there is a lengthening of the bond in the 5 membered ring (1.423Å c.f. 1.415Å). Note that in the above image, distances are given in nm to 2 decimal places. The distances as displayed for the structure in Mercury are in fact as quoted here. This is due to the donation of electron density from the sugar C-O σ orbital to the acetal C-O σ*, weakening and hence lengthening the bond. |

The Epoxides

Two epoxides will be investigated here:

1) styrene oxide

2) trans-β-methylstyrene oxide

The structures were built and optimised in Avogadro, under the MMFF94s force field, and then the Gaussian Extension was used to complete an Geometric Optimisation calculation and NMR analysis, using the B3LYP method and 6-31G(d,p) basis set (the calculations were submitted to the HPC and the the DSpace links can be found here):

1) DOI:10042/26633 . 2) DOI:10042/26634

|

Experimental [400MHz] [5] δ(ppm) | Computed δ(ppm) |

|---|---|---|

| 7.33-7.37 (m, 5H) | 6.87 (4H), 6.61 (1H) | |

| 3.85 (dd, 1H, J1¼2.6, J2¼4.0 Hz) | 3.18 (1H) | |

| 3.13 (dd, 1H, J1¼5.5, J2¼4.0 Hz) | 2.65 (1H) | |

| 2.79 (dd, 1H, J1¼5.5, J2¼2.6 Hz) | 2.12 (1H) | |

| The agreement of these calcualtions with literature is similar to that seen in earlier calculations. The key difference again is in the integration since the compuational method has not correctly identified equivalent hydrogens. The chemical shifts are experimentally found to be further downfield (by ~0.8ppm) than those calculated. In addition, coupling constants would have been more useful in this instance, for assessing the accuracy of the computational method. | ||

|

Experimental[6] δ(ppm) | Computed δ(ppm) |

|---|---|---|

| 137.6. | 134.71 | |

| 128.8 | 124.79, 124.79 | |

| 128.2 | 123.73, 123.65 | |

| 125.5 | 118.99 | |

| 52.4 | 55.01 | |

| 51.3 | 54.85 | |

| As seen earlier, at higher chemical shifts, deviations from experimental values are more pronounced. Although six carbon environments are present in the molecule, the calculation has computed 8, and these have be paired up appropriately in the table. | ||

|

Experimental [7] δ(ppm) | Computed δ(ppm) |

|---|---|---|

| 7.39-7.26 (m, 5H) | 7.50 (3H) | |

| 7.50 (3H) | ||

| 7.48 (3H) | ||

| 7.42 (1H) | ||

| 7.30 (1H) | ||

| 3.59 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H) | 3.41 (1H) | |

| 3.05 (qt, J = 5.1, 2.1 Hz, 1H) | 2.79 (1H) | |

| 1.70 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 3H) | 1.68 (1H) | |

| 1.58 (1H) | ||

| 0.72 (1H) |

|

Experimental[8] δ(ppm) | Computed δ(ppm) |

|---|---|---|

| 137.9 | 134.97 | |

| 128.6 | 124.08 | |

| 128.2 | 123.33 | |

| 125.7 | 122.80 | |

| 122.73 | ||

| 118.49 | ||

| 59.6 | 62.32 | |

| 59.2 | 60.57 | |

| 18.1 | 18.84 |

Optical Rotation of the Epoxides

In order to assign absolute configuration of the computed epoxides, the optical rotation was calculated (the "polar(optrot)" keyword was used). The table below displays the values which resulted from these calculations and literature values for comparison. DOI links to the HPC calculation have also been provided.

| Epoxide | Computed Value | Literature Value | DSpace link |

|---|---|---|---|

| Styreneoxide | -29.57 deg (chloroform, 365-589nm) | -33.3 deg (neat, 589nm, 25°C) [9] | DOI:10042/26637 |

| Methylstyreneoxide | 46.88 deg (chloroform, 365-589nm) | 47 deg (R,R)(chloroform, 589nm, 23°C) [10] | DOI:10042/26636 |

The styrene oxide was found to be the (S) enantiomer, and the methylstyene was the (R,R). It will be seen below that these are the epoxides generated from the most stable transition states.

Enantiomeric Excess from Equilibrium constant

It is possible to determine the Enantiomeric Excess (ee) of the favoured enantiomer in each epoxidation reaction. This is done by finding the Free Energy difference between the product and the opposite enantiomer.

| Styrene oxide | trans-β-methylstyrene oxide | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ΔG(S) | = -1303.738503 | ΔG(R,R) | = -1343.032443 |

| ΔG(R) | = -1303.738044 | ΔG(S,S) | = -1343.024742 |

| ΔG = ΔG(S)-ΔG(R) | = -0.000459 hartree/particle | ΔG(R,R)-ΔG(S,S) | = -0.007701 hartree/particles |

| ΔG = -RTlnk | = -1197.23 J/mol | ΔG = -RTlnk | = -20218.97 J/mol |

| k | = 1.6209 | k | = 3486.6423 |

| ee(S) | = 23.69% | ee(R,R) | = 99.94% |

| Literature e.e. | = 24% [11] | Literature e.e. | = 95.5% [12]. |

The result shows that (R,R)-methyl styrene oxide is effectively the sole product of methylstyrene epoxidation. The literature value is similar but shows a slightly lower excess, however this value shows a strong temperature dependence; ee=95.5% at -11K and in fact decreases further as the temperature is raised (at 25°C, the enantiomeric excess is approximately 92%). Solvent effects also play an important role and it is demonstrated in literature that changing the solvent can alter the ee by up to 20%.[13].

Calculations generate and enantiomeric excess of S-Styrene which fits very well indeed with experimental values, within 0.5%. This shows that the computational method can be very accurate.

Computational method has an advantage in this area because it does not encounter the effects of temperature or solvents and so all data is essentially standardised, whereas experimental data is highly dependent on such conditions.

Non-Covalent-Interaction (NCI) Analysis of the Transition States

The provided transition states were investigated and those with the lowest free energies located; NCI analysis was then conducted, generating surfaces (cubes) for the transition states of:

| 1) the epoxidation of (S)-styrene with Shi catalyst | 2) the epoxidation of (R,R)-trans-β-methylstyrene with Shi catalyst | ||||||

|

|

The Cube Type was set to "Total Density" and the Grid to "Medium" for the generation of all surfaces. The bright green surfaces represent an attractive non-covalent interaction between substrate and catalyst. As the rotatable images above demonstrate, there are many such interactions in the transition states, suggesting that these will lead to successfulcatalytic epoxidation. The slight blue colour in the middle of the green areas is indicitive of an even stronger interaction.

In the case of styrene, these primarily occur between the ethylene C=C bond and the aforementioned anomeric center of the Shi catalyst. The electrostatic interactions between the alkene hydrogens and the cyclopentyl oxygens are a major contribution to this attractive surface. The red surface (ring shaped) represents the bond formation (oxygen transfer). The approach of the terminal oxygen towards the alkene can be seen to be spiro as opposed to planar. There are also small, disc shaped green or yellow (weaker interaction) surfaces within each molecule of the transition state. These are due to hydrogen bonding or van der Waal forces. There are small repulsive forces in the middle of the 5-membered ring, perhaps due to the 2 oxygens.

The methylstyrene transition state displays a very similar surface pattern, with increased green (attractive) surfaces around the alkyl chain. The noticeable difference here is that the O-O bond has not yet broken in the transition state, and the surface representing bond formation is more blue suggesting a stronger interaction.

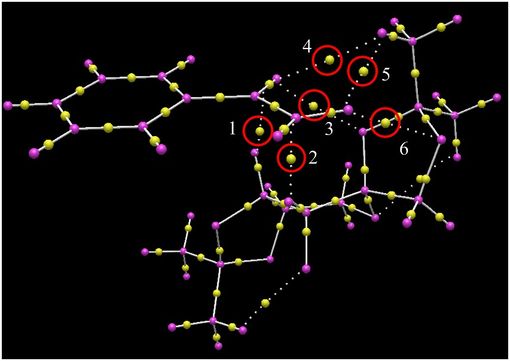

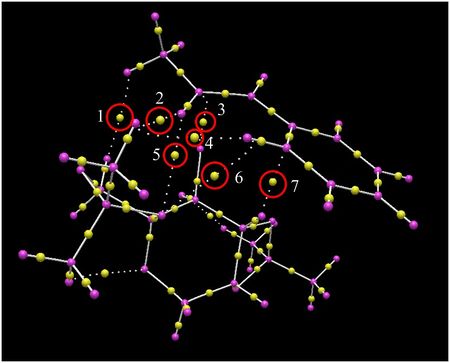

Electronic Topology (QTAIM) Analysis of the Transition States

Avogadro2 was used to provide a Quantum Theory of Atom in Molecules analysis for the same two low energy transition states. Images of these are displayed below. The yellow spots are the bond critical points (BCPs) and those of interest have been circled in red. In each instance, it can be seen that this series of BCPs are interactions (although weak) which hold the molecules together in these orientations. The BCPs themselves lie nearer to the less electronegative atom.

Suggested New Candidate for Epoxidation

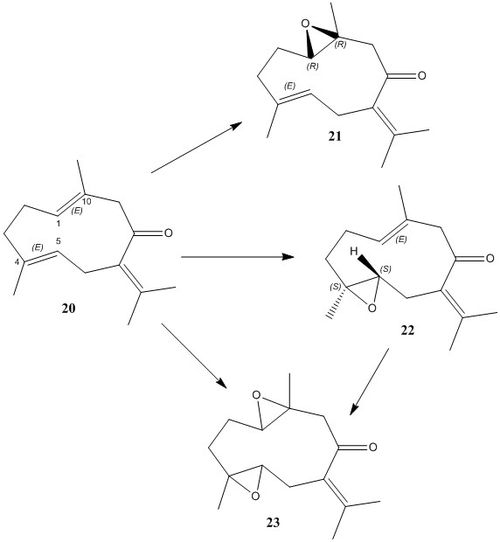

In order to to locate alkenes for further study, Reaxys was used to search for the epoxide substructure (limited to products with OPR>500). The following structure is an interesting example because it contains three alkenes, providing the possiblity for several epoxidation outcomes and a computational analysis of these would

The alkene Germacrone (20) undergoes epoxidation, as shown in the reaction scheme shown, upon treatment with the species Cunninghamella blakesleeana.[14]. The literature reports two mono-epoxide products (21 and 22) and one di-epoxide (23).

21 (germacrone-1,10-epoxide) has ORP [alpha]D=674° (436nm, 24°C)[15] and the starting alkene is available for purchase online [16] although it has now been discontinued from the Sigma Aldrich catalogue.

It would be interesting to explore the selectivity involved in this reaction, and how the epoxidation would proceed in in the presence of either the Shi ketone or Jacobsen catalyst. Such an investigation could be carried out using the procedures outlined in this report. Transition states could be located using computational techniques for each stereo-outcome and, like with the examples of styrene and methylstyrene, the lowest energy transition state could be analysed using QTAIM and NCI calculations, helping to understand any selectivity brought about through favourable non covalent interactions or steric factors.

References

- ↑ M. A. Fox, R. Cardona and N. J. Kiwiet, J. Org. Chem., 1987, 52, 1469-1474.DOI:10.1021/jo00384a016

- ↑ D. Skala and J. Hanika; Petroleum and Coal, 2003, 45, 3-4

- ↑ L. Paquette, N. A. Pegg, D. Toops, G. D. Maynard and R. D. Rogers, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1990, 112, 277-283. DOI:10.1021/ja00157a043

- ↑ J. Kim, Bull. Korean Chem. Soc., 1997, 18, 488-495, DOI:[1]

- ↑ Shallu, M.L. Sharma, J. Singh, Synthetic Communications 2012, 42, 1306-1324 DOI:10.1080/00397911.2010.539755

- ↑ Shallu, M.L. Sharma, J. Singh, Synthetic Communications 2012, 42, 1306-1324 DOI:10.1080/00397911.2010.539755 ]

- ↑ B.Wang, X.Wu, O.A Wong, B. Nettles, M. Zhao, D. Chen and Y.Shi, J. Org. Chem., 2009, 74, 3986–3989 DOI:10.1021/jo900330n

- ↑ B.Wang, X.Wu, O.A Wong, B. Nettles, M. Zhao, D. Chen and Y.Shi, J. Org. Chem., 2009, 74, 3986–3989 DOI:10.1021/jo900330n

- ↑ F.R.Jensen and R.C. Kiskis, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1975, 97, 5825-5831DOI:10.1021/ja00853a029

- ↑ G.Fronza, C.Fuganti, P.Grasselli and A.Mele, J. Org. Chem., 1991, 56, 6019-6023, DOI:10.1021/jo00021a011

- ↑ M. Hicket, D. Goeddel, Z. Crane and Y.Shi, PNAS, 2004, 101, 5794-5798, DOI:10.1073/pnas.0307548101

- ↑ Z.-X. Wang, Y. Tu, M. Frohn, J.-R. Zhang and Y. Shi, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1997, 119, 11224-11235, DOI:10.1021/ja972272g

- ↑ Z.-X. Wang, Y. Tu, M. Frohn, J.-R. Zhang and Y. Shi, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1997, 119, 11224-11235, DOI:10.1021/ja972272g

- ↑ H. Hikino, C. Konno, T. Nagashima, T. Kohama and T. Takemoto, Tetrahedron Lett., 1971, 12, 337-340, DOI:10.1016/S0040-4039(01)96435-4

- ↑ F. Bohlmann and C. Zdero, Chem. Ber, 1973, 106, 3614-3620 DOI:10.1002/cber.19731061120

- ↑ http://www.ebiochem.com/product/germacrone-98-8003