Rep:Mod:XYZ12384

EXPERIMENT 1C

Part 1

The Hydrogenation of Cyclopentadiene Dimer

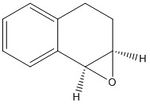

2 molecules of cyclopentadiene can react by a Diels-Alder reaction to give dicyclopentadiene. I drew molecules 1 to 4 with ChemBio3D and then opened them in Avogadro where I minimised their geometry and hence obtained a value for their energy.

| Molecule | Model | |||

| Dimer 1 (exo) |

| |||

| Dimer 1 (endo) |

| |||

| Dihydro derivative 3 |

| |||

| Dihydro derivative 4 |

|

| Dimer 1 | Dimer 2 | Dihydro derivative 3 | Dihydro derivative 4 | |

| Energy (kcal/mol) | 55.46794 | 58.19067 | 50.44566 | 41.25749 |

| Total bond stretching energy (kcal/mol) | 3.54301 | 3.46794 | 3.31218 | 2.82311 |

| Total angle bending energy (kcal/mol) | 30.77268 | 33.18929 | 31.93090 | 24.68536 |

| Total stretch bending energy (kcal/mol) | -2.04139 | -2.08220 | -2.10228 | -1.65719 |

| Total torsional energy (kcal/mol) | -2.73103 | -2.94947 | -1.46634 | -0.37840 |

| Total out of plane bending energy (kcal/mol) | 0.01485 | 0.02182 | 0.01310 | 0.00028 |

| Total van der Waals energy (kcal/mol) | 12.80164 | 12.35875 | 13.63862 | 10.63731 |

| Total electrostatic energy (kcal/mol) | 13.01367 | 14.18454 | 5.11949 | 5.14702 |

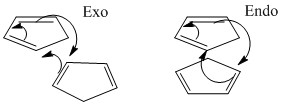

It is known that cyclopentadiene dimerises to produce specifically the endo dimer 2 rather than the exo dimer 1. The endo dimer is that with the substituents directed towards each other, whereas the exo dimer is that with the substituents away from each other. As calculated, the endo dimer is of higher energy than the exo dimer - 58kcal/mol compared to 55kcal/mol; it is reasonable to think that it would be less stable for steric reasons; so why is it the favoured product? Theories behind why are numerous, mainly involving the favourable orbital overlap in the transition state, so called secondary orbital interactions. The endo dimer is therefore the kinetic product i.e. the product formed first, although not the thermodynamically most stable, and will be formed preferentially (providing the reaction time is not overly long and the reaction temperature is not overly high).

Regarding the dihydro derivatives, derivative 4 is of lower energy than derivative 3, and is therefore more thermodynamically stable. This means that breaking the double bond in the 6-membered ring would be a reaction under thermodynamic control, whereas if the double bond in the 5-membered ring were to be broken this would be under kinetic control. Identifying why derivative 4 is more stable than derivative 3 is needed. Derivative 3 has a larger Van der Waals energy, presumably because with the double bond in the 5 membered ring, there are more steric interactions between neighbouring groups, here unfavourable. Although the derivative 3 actually has more stable torsional energy and stretch bending, it has significantly higher angle bending energy. Calculating the energy for the dihydro derivatives involved some manual manipulation of the optimised structures, especially to ensure that the labelled hydrogen atoms remained in the position that they have in the diagram.

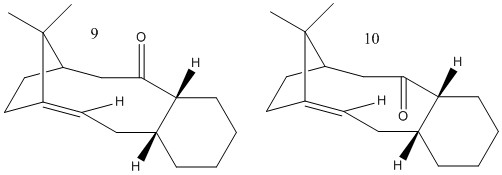

Below are pictured two atropisomers of an intermediate in the synthesis of Taxol, which differ only in whether the C=O bond points upwards or downwards. Having drawn them both in ChemBio3D, I proceeded to minimise their geometry in Avogadro to determine which is the most stable. This required much manual manipulation of the geometry to ensure that the rings displayed the correct conformation, in particular.

| Intermediate 9 | Intermediate 10 | |

| Energy (kcal/mol) | 121.81932 | 126.32222 |

| Total bond stretching energy (kcal/mol) | 12.98361 | 14.85958 |

| Total angle bending energy (kcal/mol) | 50.10469 | 48.00565 |

| Total stretch bending energy (kcal/mol) | -0.49774 | -0.60146 |

| Total torsional energy (kcal/mol) | 8.17105 | 8.49999 |

| Total out of plane bending energy (kcal/mol) | 2.63558 | 2.60344 |

| Total van der Waals energy (kcal/mol) | 46.85942 | 51.07448 |

| Total electrostatic energy (kcal/mol) | 1.56271 | 1.88054 |

From this initial energy determination, it is apparent that intermediate 9 is of slightly lower energy than intermediate 10, however this difference is quite slight, and could have been reversed, depending on the quantity and quality of the optimisations. Although I went through several stages of optimising the structures, it was difficult to obtain more than slight decreases in energy each time. In theory, intermediate 9 should have its C ring in a twist boat form, which I think I achieved, with that for intermediate 10 in a chair form, which was harder to keep.

| Molecule | Model | |||

| Intermediate 9 |

| |||

| Intermediate 10 |

|

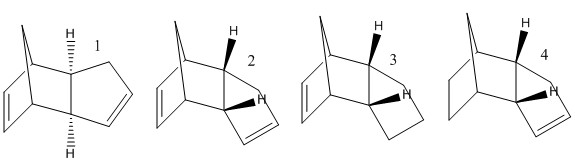

Hyperstable alkenes

Alkenes such as this are described as 'hyperstable'. This is because of their position at a bridgehead which stabilises the alkene. Of course an alkene in such a ring has a degree of strain; yet the alkene has reduced strain compared to its corresponding alkane and hence the hydrogenation enthalpy for such alkenes is less than for more typical alkenes, removing the thermodynamic driving force for the reaction. The presence of the methyl groups on the bridge reinforces this effect; it would indeed be even more pronounced with more sterically demanding groups.

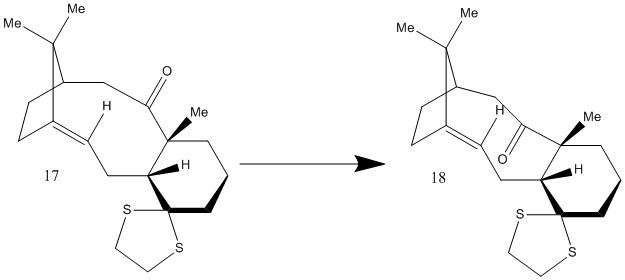

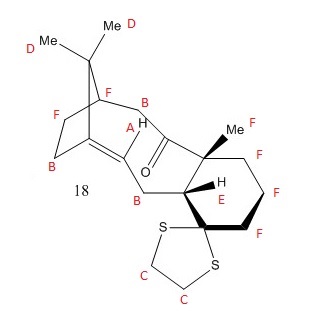

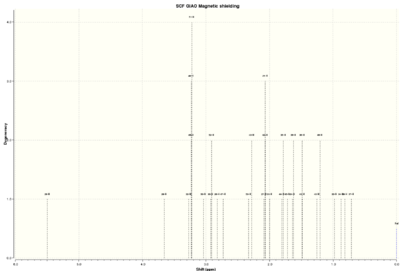

Derivatives of intermediates 9 and 10, so-called intermediates 17 and 18, are pictured here. It was my job to calculate both 1H and 13C NMR spectra for these molecules, after first optimising their geometry, as above.

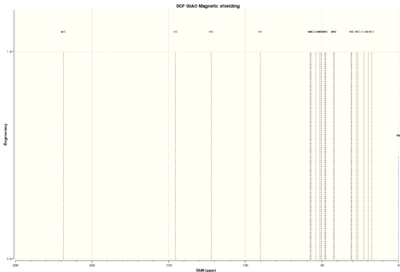

Taxol intermediate 18

Spectra

Data

13C

| Chemical shift (ppm) (x-axis) | Intensit (y-axis) | Degeneracy | Literature value of chemical shift (ppm) | Chemical shift percentage difference (%) | |

| 14-C | 218.7122426 | 1 | 1 | 211.49 | 3.42 |

| 3-C | 145.566623 | 1 | 1 | 148.72 | 2.12 |

| 6-C | 122.1221296 | 1 | 1 | 120.90 | 1.01 |

| 9-C | 90.25778571 | 1 | 1 | 74.61 | 21.0 |

| 13-C | 57.57937432 | 1 | 1 | 60.53 | 4.87 |

| 8-C | 56.98823281 | 1 | 1 | 51.30 | 11.1 |

| 4-C | 53.93147108 | 1 | 1 | 50.94 | 5.87 |

| 16-C | 51.45746873 | 1 | 1 | 45.53 | 13.0 |

| 10-C | 50.32133636 | 1 | 1 | 43.28 | 16.3 |

| 22-C | 47.94804848 | 1 | 1 | 40.82 | 17.5 |

| 5-C | 47.62182749 | 1 | 1 | 38.73 | 23.0 |

| 21-C | 42.12141597 | 1 | 1 | 36.78 | 14.5 |

| 12-C | 42.00330074 | 1 | 1 | 35.47 | 18.4 |

| 7-C | 30.87297377 | 1 | 1 | 30.84 | 0.107 |

| 2-C | 30.5765739 | 1 | 1 | 30.00 | 1.92 |

| 1-C | 27.36074611 | 1 | 1 | 25.56 | 7.05 |

| 17-C | 26.48312723 | 1 | 1 | 25.35 | 4.47 |

| 11-C | 22.50667999 | 1 | 1 | 22.21 | 1.34 |

| 18-C | 19.71519254 | 1 | 1 | 21.39 | 7.83 |

| 19-C | 17.49142381 | 1 | 1 | 19.83 | 11.8 |

Reference: TMS B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) chloroform; Reference shielding: 192.17 ppm; NMR Degeneracy Tolerance: 0.05

1H

| Chemical shift (ppm) (x-axis) | Intensity (y-axis) | Degeneracy | Literature value of chemical shift (ppm) | |

| 31-H | 5.033281522 | 1 | 1 | 5.21 |

| 53-H | 3.287281382 | 1 | 1 | 3-2.7 |

| 52-H | 3.171685827 | 1 | 2 | |

| 50-H | 3.162427902 | 2 | 2 | |

| 34-H | 3.031182432 | 1 | 2 | |

| 51-H | 3.025883691 | 2 | 1 | |

| 32-H | 2.929098468 | 1 | 1 | |

| 25-H | 2.702363379 | 1 | 1 | 2.7-2.35 |

| 33-H | 2.639715167 | 1 | 1 | |

| 29-H | 2.510863665 | 1 | 3 | |

| 30-H | 2.474489955 | 2 | 3 | |

| 44-H | 2.467717465 | 3 | 3 | 2.2-1.7 |

| 36-H | 2.321118582 | 1 | 4 | |

| 24-H | 2.28204336 | 2 | 4 | |

| 35-H | 2.24094819 | 3 | 4 | |

| 27-H | 2.232855901 | 4 | 4 | |

| 28-H | 2.125579451 | 1 | 1 | |

| 26-H | 1.708709036 | 1 | 3 | 1.58 |

| 38-H | 1.672449177 | 2 | 3 | 1.5-1.2 |

| 48-H | 1.64327592 | 3 | 3 | |

| 39-H | 1.520852921 | 1 | 2 | |

| 41-H | 1.511494528 | 2 | 2 | 1.1 |

| 37-H | 1.416837673 | 1 | 3 | |

| 47-H | 1.402531022 | 2 | 3 | |

| 40-H | 1.365898688 | 3 | 3 | 1.07 |

| 49-H | 1.0293207 | 1 | 1 | |

| 46-H | 0.905573979 | 1 | 4 | |

| 42-H | 0.884744233 | 2 | 4 | 1.03 |

| 43-H | 0.857346606 | 3 | 4 | |

| 45-H | 0.843911059 | 4 | 4 |

Reference: TMS B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) chloroform; Reference shielding: 31.7462 ppm; NMR Degeneracy Tolerance: 0.05

It is a little harder to directly compare the calculated NMR data with that from literature for 1H NMR due to the presence of multiplets. An important piece of information that is missing from the calculated data is the coupling constants, but this takes a lot of computation time.

Some assignments can be made for specific H atoms. The alkene proton (A) is likely to be at 5.1ppm, with the four sulphide protons (C) at 2.7-2.35ppm. The B protons could be at 3-2.7ppm. D at 2.2-1.7ppm; E at 1.58ppm;

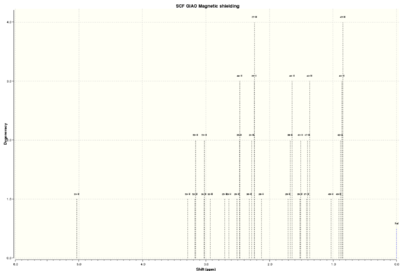

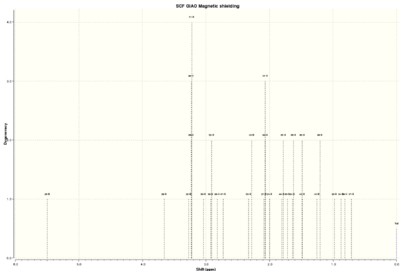

Taxol Intermediate 17

Spectra

Data

13C

| Chemical shift (ppm) (x-axis) | Intensity (y-axis) | Degeneracy | Literature value of chemical shift (ppm) | Chemical shift percentage difference(%) | |

| 9-C | 217.61 | 1 | 1 | 218.79 | 0.54 |

| 5-C | 159.17 | 1 | 1 | 144.63 | 10.1 |

| 15-C | 121.60 | 1 | 1 | 125.33 | 2.98 |

| 7-C | 94.23 | 1 | 1 | 72.88 | 29.3 |

| 8-C | 62.56 | 1 | 1 | 56.19 | 11.3 |

| 10-C | 60.09 | 1 | 1 | 52.52 | 14.4 |

| 20-C | 47.39 | 1 | 1 | 48.50 | 2.47 |

| 4-C | 44.95 | 1 | 1 | 46.80 | 3.95 |

| 21-C | 43.05 | 1 | 1 | 45.76 | 5.92 |

| 23-C | 42.85 | 1 | 1 | 39.80 | 7.67 |

| 6-C | 42.01 | 1 | 1 | 38.81 | 8.25 |

| 2-C | 40.84 | 1 | 1 | 25.85 | 13.9 |

| 18-C | 37.12 | 1 | 1 | 32.66 | 13.7 |

| 16-C | 33.38 | 1 | 1 | 28.79 | 15.9 |

| 1-C | 33.33 | 1 | 1 | 28.29 | 17.8 |

| 17-C | 30.43 | 1 | 1 | 26.88 | 13.2 |

| 11-C | 22.75 | 1 | 1 | 25.66 | 11.3 |

| 12-C | 22.46 | 1 | 1 | 23.86 | 5.87 |

| 14-C | 22.28 | 1 | 1 | 20.96 | 6.30 |

| 19-C | 21.72 | 1 | 1 | 18.71 | 16.1 |

Reference: TMS B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) chloroform; Reference shielding: 192.17 ppm; NMR Degeneracy Tolerance: 0.05

1H

| Chemical shift (ppm) (x-axis) | Intensity (y-axis) | Degeneracy | Literature value of chemical shift (ppm) | |

| 29-H | 5.50 | 1 | 1 | 4.84 |

| 28-H | 3.65 | 1 | 1 | 3.4-3.10 |

| 32-H | 3.27 | 1 | 4 | |

| 49-H | 3.23 | 2 | 4 | |

| 48-H | 3.23 | 3 | 4 | |

| 51-H | 3.22 | 4 | 4 | 2.99 |

| 50-H | 3.04 | 1 | 1 | 2.80-1.35 |

| 30-H | 2.92 | 1 | 2 | |

| 52-H | 2.91 | 2 | 2 | |

| 26-H | 2.82 | 1 | 1 | |

| 47-H | 2.73 | 1 | 1 | |

| 53-H | 2.33 | 1 | 2 | |

| 43-H | 2.28 | 2 | 2 | |

| 27-H | 2.09 | 1 | 3 | |

| 42-H | 2.07 | 2 | 3 | |

| 25-H | 2.07 | 3 | 3 | |

| 31-H | 2.00 | 1 | 1 | |

| 44-H | 1.81 | 1 | 2 | |

| 35-H | 1.78 | 2 | 2 | |

| 45-H | 1.72 | 1 | 1 | |

| 24-H | 1.64 | 1 | 2 | 1.38 |

| 39-H | 1.62 | 2 | 2 | |

| 41-H | 1.48 | 1 | 2 | |

| 36-H | 1.48 | 2 | 2 | 1.25 |

| 40-H | 1.25 | 1 | 2 | |

| 46-H | 1.20 | 2 | 2 | |

| 33-H | 0.98 | 1 | 1 | 1.10 |

| 34-H | 0.87 | 1 | 1 | |

| 38-H | 0.82 | 1 | 1 | |

| 37-H | 0.71 | 1 | 1 | 1.00-0.80 |

Reference: TMS B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) chloroform; Reference shielding: 31.7462 ppm; NMR Degeneracy Tolerance: 0.05

Further optimisation of the structures would have led to NMR spectra that are closer to those of the literature. All NMR data for intermediates 17 and 18 originates from the same source.[1] Although there is a degree of similarity between the calculated and literature data - they are at least recognisable and vaguely diagnostic of a particular molecule - some of the percentage differences are very large. It is possible that literature values could be incorrect; in this case I believe it is my unskilled ability in optimising the structures of the molecules that is mainly responsible for the differences.

In addition to calculating NMR spectra, it was possible to obtain values for the free energies of the two intermediates. This is given by the 'Sum of electronic and thermal free energies' in the output file.

Sum of electronic and thermal free energies = -1651.469051, for intermediate 18

Sum of electronic and thermal free energies = -1651.38004, for intermediate 17

This shows that intermediate 18, with the 'tucked under' C=O is of slightly lower energy than intermediate 17. This confirms that the direction of the arrow in the above image is correct (or at least a version of the true equilibrium). Intermediate 18 has a structure that minimises steric interactions between non-bonded groups.[2]

Part 2

Analysis of the properties of the synthesised alkene epoxides

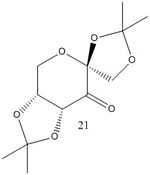

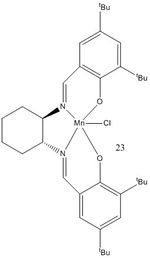

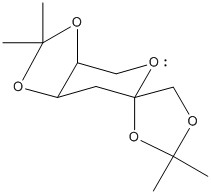

Whilst in the lab during Experiment 1S, in pairs we synthesised both Jacobsen and Shi catalysts. Once given a set of 4 alkenes - styrene, β-methyl styrene, trans-stilbene and 1,2-dihydronaphthalene - we proceeded to carry out asymmetric epoxidation of these alkenes using the aforementioned catalysts. Reproduced here are the structures of stable pre-catalysts 21 and 23.

| Name | Structure |

| Pre-catalyst 21 | |

| Pre-catalyst 23 |

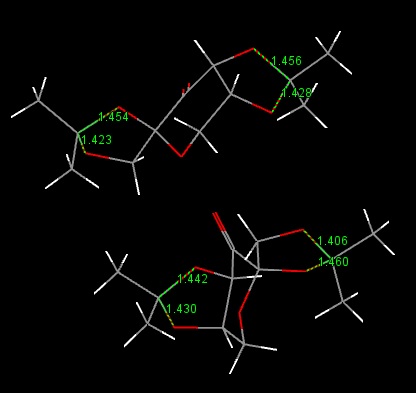

The crystal structures of the two catalysts

I searched for the structure of pre-catalyst 21 on the Cambridge Crystal Database. Its reference is NELQEA01. I measured the 2 C-O bond lengths for each anomeric centre. As shown in the diagram, the sets of C-O lengths are: 1.456/1.428 and 1.454/1.423; 1.442/1.430 and 1.460/1.406. What is surprising is that for each anomeric centre, the two C-O bond lengths are not of the same length; in fact there is a definite longer and shorter bond although both are typical of such a C-O bond (with some variation between the actual lengths for each anomeric centre). This must mean that one of the C-O bonds has more double bond character than the other. The 6 membered ring can be drawn in a chair form as below (additional substituents have been discarded). This puts one of the C-O bonds for each anomeric centre axial and one equatorial. Possible reactions include elimination of a H anti-periplanar to a C-O leading to formation of an alkene and O-, or equivalent with the O lone pair.

I also looked for the crystal structure of pre-catalyst 23 on the Cambridge Crystal Database. The reference is TUVNIB01. As shown on the diagram, the closest approach between adjacent t-Bu groups on the rings (H-H) was found to be 2.081. This is surprisingly close, especially considering that the closest approach for two t-Bu groups on the ring was found to be 3.602 or 3.557 for each ring.

The calculated NMR properties of your products

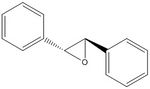

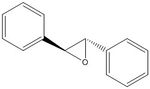

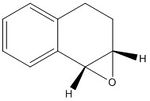

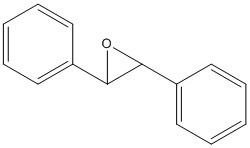

I calculated both 1H and 13C NMR spectra for the epoxides of both trans-stilbene and 1,2-dihydro naphthalene, with undefined stereochemistry. These are a complementary pair to use, as trans-stilbene is a trans alkene and 1,2-dihydro naphthalene is a cis alkene.

| Molecule | NMR spectrum | DOI |

| Epoxide of trans-stilbene: 13C | DOI:10042/25974 | |

| Epoxide of trans-stilbene: 1H | DOI:10042/25974 | |

| Epoxide of 1,2-dihydronaphthalene: 13C | DOI:10042/25973 | |

| Epoxide of 1,2-dihydronaphthalene: 1H | DOI:10042/25973 |

Reference NMR data for epoxide of trans-stilbene: 1H NMR (300MHz, CDCl3) Chemical shift (ppm): 3.86 (s,2H), 7.26-7.45 (m,10H) The calculated values are 3.54, 7.45-7.57, which is a fairly good match.

13C NMR (75MHz, CDCl3) Chemical shift (ppm): 62.81, 125.4, 128.19, 128.44, 136.99. The calculated values are 66.43, 118.27, 123.08, 123.21, 123.52, 124.22, 134.08. Although these figures do not exactly match, and there is overlap within the sets, taking each shift to be related to its partner compares well (i.e. good percentage difference.)

Reference NMR data for epoxide of 1,2-dihydronaphthalene:

1H NMR (CDCl3) Chemical shift (ppm): 1.65 (m,1H), 2.30 (m,1H), 2.44(m,1H), 2.68(m,1H), 3.62 (m,1H), 3.74 (d,J=4,1H), 6.98 (d,J=7, 1H), 7.08-7.17 (m,2H), 7.28 (d,J=8,1H).

The calculated values are 1.87, 2.21, 2.27, 2.95, 3.48, 3.55, 7.25, 7.39, 7.61. These values are less of a good match, probably suggesting that the structure of the rings needed further optimisation.

13C NMR (CDCl3) Chemical shift (ppm): 21.8,24.4,52.7,55.1,126.1,2x128.4,129.5,132.6,136.7.

The calculated values are 29.1, 30.2, 52.1, 52.8, 121.7, 123.5, 123.8, 126.7, 130.4, 135.4. Although the match improves (and any difference becomes less significant) for the higher chemical shift values, there is a fairly large mismatch for the lower chemical shifts.

In conclusion, the literature values tend to support those that which were calculated, with some variation.

Assigning the absolute configuration of the product

The reported literature for optical rotations and the calculated chiroptical properties of the products

I looked on Reaxys for optical rotatory power literature values for each epoxide - both isomers - of the four alkenes. I also calculated values for one of the two isomers (assuming that calculation of the other isomer would return a result equal in magnitude but opposite in sign). Although I did not fully optimise the structures, and hence the obtained values do not match the literature values at all well in magnitude, the main purpose of this search is to check that the values have the correct sign of rotation. The magnitude of optical rotation values on Reaxys varies a lot; as well as the sign of the optical rotation, particularly for styrene oxide.

(R,R) epoxide of trans-stilbene: 310 deg [5]; (S,S) epoxide of trans-stilbene: -313 deg [6]

I calculated an optical rotation for the (R,R) epoxide of trans-stilbene as 30.74 deg. DOI:10042/26005

(S,S) epoxide of β-methyl styrene: -41.8 deg. [7]; (R,R) epoxide of β-methyl styrene: 40.8 deg. [8]

I calculated an optical rotation for the (S,S) epoxide of β-methyl styrene as -118.47 deg. DOI:10042/26004

(S) epoxide of styrene: -44.5 deg. [9]; (R) epoxide of styrene: 42.7 deg. [10]

I calculated an optical rotation for the(R) epoxide of styrene as 180.06 deg (DOI:10042/26001 ) and for the (S) epoxide of styrene as -182.37 deg (DOI:10042/26002 ) (very almost equal and opposite.)

(1S,2R) epoxide of 1,2-dihydronaphthalene: -134.5 deg. [11]; (1R,2S) epoxide of 1,2-dihydronaphthalene: 133 deg. [12]

I calculated an optical rotation for the (1R,2S) epoxide of 1,2-dihydronaphthalene as 52.74 deg. DOI:10042/26003

In conclusion, the calculated optical rotations indicate that the literature references included are correct. However, it was the case that some of the literature assignments had signs for the optical rotation which were incorrect. Images of each isomer are included below for clarity.

| Name | Structure |

| (R,R) epoxide of trans-stilbene | |

| (S,S) epoxide of trans-stilbene | |

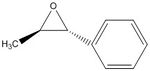

| (R,R) epoxide of β-methyl styrene | |

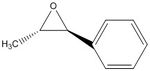

| (S,S) epoxide of β-methyl styrene | |

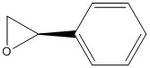

| (R) epoxide of styrene | |

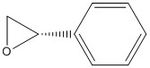

| (S) epoxide of styrene | |

| (1R,2S) epoxide of 1,2-dihydronaphthalene | |

| (1S,2R) epoxide of 1,2-dihydronaphthalene |

I additionally calculated VCD (vibrational circular dichroism) spectra for one of the two isomers of each epoxide (the same isomers that were used for calculation of optical rotation for comparison; again with both (R) and (S) epoxides of styrene as a check). Although I attempted to create ECD (electronic circular dichroism) spectra as well, I ought to have heeded the advice that this wasn't appropriate in this case because these epoxides lack an appropriate chromophore.

| Molecule | VCD spectrum | DOI |

| (R,R) epoxide of trans-stilbene | DOI:10042/25997 | |

| (S,S) epoxide of β-methyl styrene | DOI:10042/25998 | |

| (R) epoxide of styrene | DOI:10042/26000 | |

| (S) epoxide of styrene | DOI:10042/25996 | |

| (1R,2S) epoxide of 1,2-dihydronaphthalene | DOI:10042/25999 |

The (R) and (S) epoxides of styrene can be seen to have a degree of symmetry about the centre axis. Particularly, in the VCD spectrum for the (R) epoxide the peak at ~700 is positive, whilst that at ~1500 is negative, whereas this is reversed for the (S) epoxide. With additional time, I would have searched for literature VCD spectra to compare.

Using the (calculated) properties of transition state for the reaction

Transition states for Shi epoxidation of trans-β-methyl styrene

| Free energy G (Hartrees): R,R series | Free energy G (Hartrees): S,S series | Difference in energy (R,R)-(S,S) in Hartrees | in kJ/mol | K | Enantiomeric excess |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -1343.022970 | -1343.017942 | -0.005028 | -13.201015006 | 4.85x10^-3 | 99.0% |

| -1343.019233 | -1343.015603 | -0.003630 | -9.530565726 | 0.0213 | 95.8% |

| -1343.029272 | -1343.023766 | -0.005506 | -14.4560041 | 2.92x10^-3 | 99.4% |

| -1343.032443 | -1343.024742 | -0.007701 | -20.21897704 | 2.86x10^-4 | 99.9% |

On first inspection, without any further analysis, it appears that the R,R series of transition states for the Shi epoxidation of trans-β-methyl styrene are of lower energy than the S,S series of transition states. This suggests that the (R,R) epoxide of trans-β-methyl styrene would be preferentially formed over the (S,S) epoxide, which fits with both literature results[13] and what I observed whilst in the wet lab 1S.

Steps I took to calculate enantiomeric excess:

- I found the difference in energy - dG - between each (R,R) and (S,S) transition state.

- I then converted the energy values from Hartrees (as is provided in the output files) into kJ/mol.

- Using dG=-RTlnK, and rearranging to give K=exp(-dG/RT) allows values of K to be found for each transition state (with R=8.314J/molK, and T=298K). K can be viewed as a ratio between the two possible products.

- I put K = 1-X/X, rearranged to X=1/1+K, where X is the mole fraction of 1 of the isomers. The enantiomeric excess is the fraction of 1 isomer - the fraction of the 2nd isomer.

The literature enantiomeric excess for Shi epoxidation of trans-β-methyl styrene is 91-92%. Although the calculated values for the enantiomeric excess of the transition states are higher than this, when combined it is brought down to 94%, closer to literature. [14]

Transition states for Jacobsen epoxidation of trans-β-methyl styrene

| Free energy G (Hartrees): R,R series | Free energy G (Hartrees): S,S series | Difference in energy (R,R)-(S,S) in Hartrees | in kJ/mol | K | Enantiomeric excess |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -3383.253816 | -3383.262481 | 0.008665 | 22.7499592 | 1.03x10^-4 | 99.97%(!) |

| -3383.254344 | -3383.257847 | 0.003503 | 9.1971272 | 0.0244 | 95.2% |

Again, by first inspection, this time it is the S,S series of transition states that are of lower energy, suggesting that the (S,S) epoxide would be formed preferentially. I again calculated the enantiomeric excess for the transition states.

So, for a trans alkene, Shi epoxidation supposedly leads to the (R,R) epoxide and Jacobsen epoxidation leads to the (S,S) epoxide. How about for a cis alkene?

Transition states for Shi epoxidation of 1,2-dihydronaphthalene

| Free energy G: R,S series | Free energy G: S,R series | Difference in energy (R,S)-(S,R) |

|---|---|---|

| -1381.120782 | -1381.131343 | 0.010561 |

| -1381.125886 | -1381.116109 | -0.009777 |

| -1381.134059 | -1381.126059 | -0.008 |

| -1381.126722 | -1381.136239 | 0.009517 |

Here, there is no immediately clear way to determine which of the series is of lower energy. I would expect it to be the (R,S) series, but the pair with the largest energy difference is that with the (S,R) transition state lower in energy.

Transition states for Jacobsen epoxidation of cis-β-methyl styrene

| Free energy G: R,S series | Free energy G: S,R series | Difference in energy (R,S)-(S,R) |

|---|---|---|

| -3383.251060 | -3383.259559 | 0.008499 |

| -3383.250270 | -3383.253442 | 0.003172 |

This time it is clear that the (S,R) series of transition states is more stable than the (R,S) series.

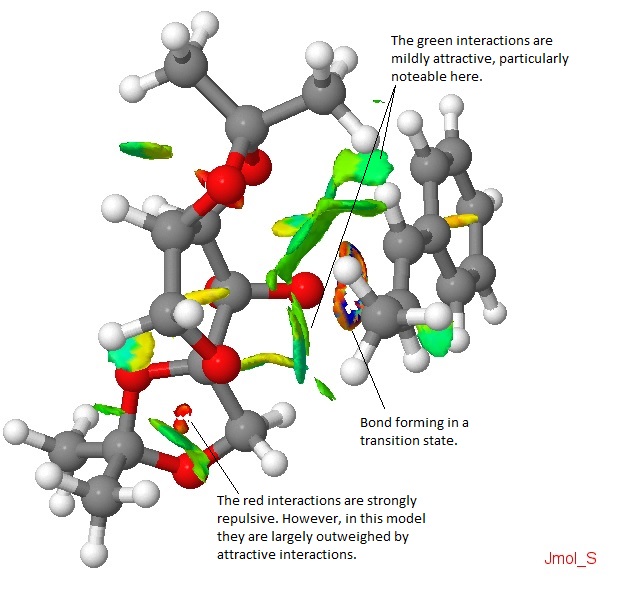

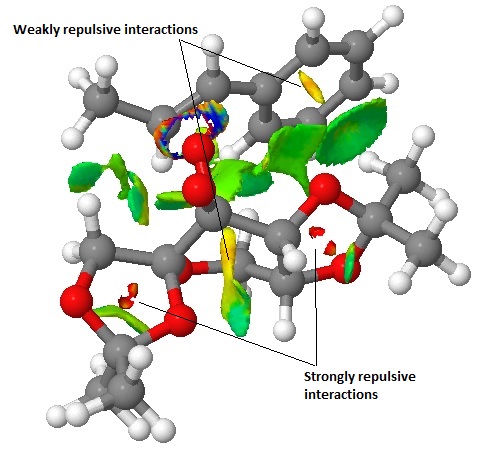

Investigating the non-covalent interactions in the active-site of the reaction transition state

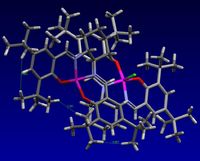

I chose one of the included transition states and subjected it to a NCI analysis. The transition state used is the second in the (R,R) series for the Shi epoxidation of trans-β-methyl styrene (chosen more or less randomly.) The result is pictured here, with the Shi catalyst to the left of the image and the alkene to the right.

Just by looking at the image, it is clear that there are very few repulsive interactions, and an extended degree of attractive interactions. The bond forming between the two molecules can be seen. It is believable that the pictured transition state is indeed particularly low in energy and would lead to the (R,R) product preferentially over the (S,S) product.

This is the corresponding (S,S) transition state to that above. Although there is still a very large degree of attractive interactions, there is slightly more repulsive interactions; definitely more of the slightly repulsive regions (yellow) have a greater amount of strongly repulsive character (red) than before, raising the energy of this transition state above that of the other. However, of the entire series, these are two of the transition states which are most similar in energy, hence may not have been the best pair to analyse(!). It would seem that it is the relative energies of the other transition states in the same series that may have more of an effect leading to the preferential production of one isomer over the other.

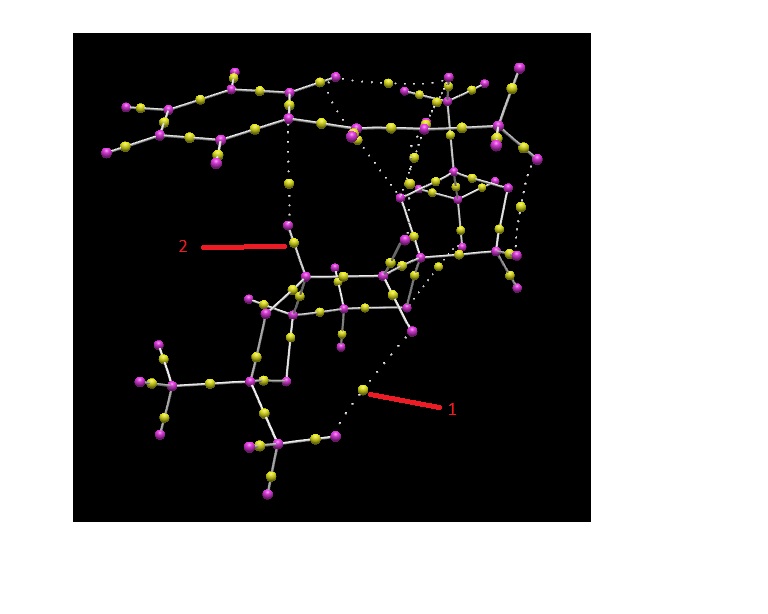

Investigating the Electronic topology (QTAIM) in the active-site of the reaction transition state

I used the same transition state as for the NCI analysis, and subjected it to a QTAIM analysis. The model shows BCPs - Bond topological Critical Points - as the yellow spheres between two nuclei. Those BCPs associated with a solid white line indicate the presence of a bond, whereas those with a dashed line demonstrate a weaker, non-covalent interaction. A molecule of trans-β-methyl styrene is in the bottom right corner of the frame, with the Shi catalyst above it. The weak, non-covalent interactions are those between the two molecules in this transition state, whilst the covalent interactions are those known to be in the molecules (and are hence less interesting.)

I have labelled a few BCPs which are particularly interesting:

- 1. This weak, non-covalent BCP has a more pronounced curve than any other.

- 2. This BCP demonstrates that the BCP can be positioned much closer to one atom than the other.

- 3. This non-covalent BCP is, at first glance, the one forming between the two furthest away atoms, both within the catalyst itself.

- 4,5,6 Alongside 3, these BCPs are between atoms that one might not necessarily expect to interact due to their distance and geometry.

Suggesting new candidates for investigations

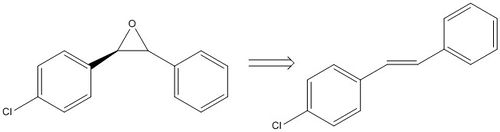

I carried out a search on Reaxys for epoxides with optical rotary power greater than 500 or less than -500. This returned a surprisingly large number of results. One such epoxide is pictured below is called trans-1-(p-Chlorphenyl)-2-phenylethenoxid. It has an optical rotary power of 780 deg. [15] Its corresponding alkene is also pictured below, and is called 1-(4-chlorophenyl)-2-phenyl-ethylene. It at least produces one search result on Sigma Aldrich which is more than the other alkenes I tried(!).

References

- ↑ L. A. Paquette, N. A. Pegg, D. Toops, G. D. Maynard, R. D. Rogers, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 1990, 112, 277-283.

- ↑ L. A. Paquette, N. A. Pegg, D. Toops, G. D. Maynard, R. D. Rogers, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 1990, 112, 277-283

- ↑ R. W. Murray, M. Singh, Organic Syntheses Coll., 1998, 9, 288

- ↑ K. Smith, C-H. Liu, G. A. El-Hiti, Organic and Biomolecular Chemistry, 2006, 4, #5, 917-927

- ↑ R. I. Kureshy, S. Singh, N. H. Khan, S. H. R. Abdi, S. Agrwawal, R. V. Jasra, Tetrahedron: Assymetry, 2006, 17, #11, 1638-1643

- ↑ Read, Campbell, Nature, 1930, 125, 16

- ↑ H. Lin, Y. Liu, Z-L. Wu, Tetrahedron: Assymetry, 2011, 22, #2, 134-137

- ↑ B. Wang, X-Y. Wu, O. A. Wong, B. Nettles, M-X Zhao, D. Chen, Shi, Yian, Journal of Organic Chemistry, 2009, 74, #10, 3986-3989

- ↑ B. T. Cho, W. K. Yang, O.K. Choi, Journal of the Chemical Society, Perkin Transactions 1, 2001 , #10, 1204-1211

- ↑ E. J. Corey, C. J. Helal, Tetrahedron Letters, 1993, 34, # 33, 5227-5230

- ↑ A. Shcmid, K. Hofstetter, H-J. Feiten, F. Hollmann, B. Witholt, Advanced Synthesis and Catalysis, 2001, 343, #6-7, 732-737

- ↑ D. R. Boyd, N. D. Sharma, R. Agarwal, N. A. Kerley, R. A. S. McMordie, et al, Journal of the Chemical Society Chemical communications, 1994, #14, 1693-1694

- ↑ Z-X. Wang, L. Shu, M. Frohn, Y. Tu, Y. Shi, Organic Syntheses, 2003, 80, 9

- ↑ Z-X. Wang, L. Shu, M. Frohn, Y. Tu, Y. Shi, Organic Syntheses, 2003, 80, 9

- ↑ P. M. Dansette, H. Ziffer, D. M. Jerina, Tetrahedron, 1976, 32, 2071-2074