Rep:Mod:W41DATW

Y3C: Compulsory Section

Molecular Optimizations

The following molecules were created in GaussView 5.0.9 and optimized using Gaussian, processed either on issued hardware or on the 4px HPC setup.

BH3 Optimizations

| Criterion | Value |

|---|---|

| File Type | .log |

| Calculation Type | FOPT |

| Method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | 3-21G |

| Final Energy (au) | -26.4622643 |

| Gradient (au) | 0.000089 |

| Dipole Moment (D) | 0.00 |

| Point Group | CS |

| Calculation Time (s) | 11.0 |

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000220 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000106 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000709 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000447 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-1.672478D-07

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

----------------------------

! Optimized Parameters !

! (Angstroms and Degrees) !

-------------------------- --------------------------

! Name Definition Value Derivative Info. !

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

! R1 R(1,2) 1.1947 -DE/DX = -0.0002 !

! R2 R(1,3) 1.1948 -DE/DX = -0.0002 !

! R3 R(1,4) 1.1944 -DE/DX = -0.0001 !

! A1 A(2,1,3) 120.0157 -DE/DX = 0.0 !

! A2 A(2,1,4) 119.9983 -DE/DX = 0.0 !

! A3 A(3,1,4) 119.986 -DE/DX = 0.0 !

! D1 D(2,1,4,3) 180.0 -DE/DX = 0.0 !

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The bond lengths (Å) generated by this calculation setup were found to be 1.19. The bond angles about the central boron atom were found to be 120°. In this calculation, a fairly small basis set of 3-21G was used, a so-called split valence basis set, where there are different sizes to represent the same AO.[1]

| Criterion | Value |

|---|---|

| File Type | .log |

| Calculation Type | FOPT |

| Method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | 6-31G(d,p) |

| Final Energy (au) | -26.6153237 |

| Gradient (au) | 0.000018 |

| Dipole Moment (D) | 0.00 |

| Point Group | CS |

| Calculation Time (s) | 3.0 |

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000019 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000013 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000090 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000047 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-2.988787D-09

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

----------------------------

! Optimized Parameters !

! (Angstroms and Degrees) !

-------------------------- --------------------------

! Name Definition Value Derivative Info. !

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

! R1 R(1,2) 1.1924 -DE/DX = 0.0 !

! R2 R(1,3) 1.1923 -DE/DX = 0.0 !

! R3 R(1,4) 1.1923 -DE/DX = 0.0 !

! A1 A(2,1,3) 119.9883 -DE/DX = 0.0 !

! A2 A(2,1,4) 119.9991 -DE/DX = 0.0 !

! A3 A(3,1,4) 120.0126 -DE/DX = 0.0 !

! D1 D(2,1,4,3) 180.0 -DE/DX = 0.0 !

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Using the 6-31G(d,p) basis set the bond lengths (Å) were found to be 1.19. Meanwhile the bond angles were found to be 120.0°. This time a higher basis set of 6-31G(d,p) was used, which is known to add p functions and d functions to hydrogen atoms and heavy atoms respectively. This is known as a polarized basis set, which allow the orbitals to transform their shape.[1]

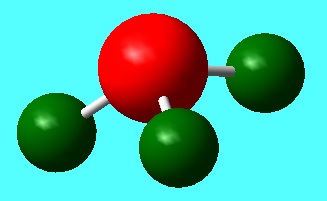

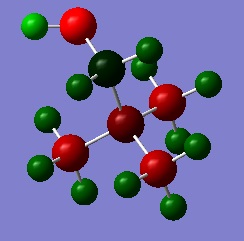

GaBr3 Optimization

| Criterion | Value |

|---|---|

| File Type | .log |

| Calculation Type | FOPT |

| Method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | LANL2DZ |

| Final Energy (au) | -41.7008273 |

| Gradient (au) | 0.000000 |

| Dipole Moment (D) | 0.0000 |

| Point Group | D3h |

| Calculation Time (s) | 11.4 |

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000000 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000000 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000003 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000002 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-1.282696D-12

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

All bond lengths and bond angles were found to be identical, 2.35 Å and 120.00° respectively, due to the locking of D3h symmetry. This DSpace link will access the files created for this optimization.

BBr3 Optimization

| Criterion | Value |

|---|---|

| File Type | .log |

| Calculation Type | FOPT |

| Method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | Gen |

| Final Energy (au) | -64.4364492 |

| Gradient (au) | 0.000012 |

| Dipole Moment (D) | 0.0009 |

| Point Group | CS |

| Calculation Time (s) | 19.0 |

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000035 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000020 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000207 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000125 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-5.434842D-09

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

The bond lengths (Å) in BBr3 were found to be 1.93. The 3 bond angles were discovered to be 120.0°. The corresponding DSpace page includes all information from the generated calculations.

Analysis

| Molecule | Average Bond Length (Å) | Literature Bond Length (Å) |

|---|---|---|

| BH3 | 1.19 | 1.19[2] |

| GaBr3 | 2.35 | 2.24[3] |

| BBr3 | 1.93 | 1.90[4] |

Changing the substituents from H to Br in the trigonal planar molecule examined above leads to an increase in bond length. Bromine atoms are much larger in mass (approximately 80 times) than hydrogen atoms, whilst also needing to accommodate more electrons around the nucleus. The crystallographic Van der Waal's radius is larger for bromine than hydrogen, 1.9 Å[5] and 1.2 Å[5] respectively and this is reflected in the bond lengths above in the fact bromine caters for p and d orbitals. When comparing the Pauling electronegativites of bromine (2.96) and hydrogen (2.20), there is a difference of 0.76. With the knowledge that the Pauling electronegativity of boron is 2.04, we can infer that the B-Br bond is more ionic in character than the B-H bond. The sheer difference in size between H and Br outweighs the contribution of electronegativity. A similarity between H and Br is their affinity to create one bond per atom.

By changing the central element in the molecule from boron to gallium, an increase in average bond length was observed. Gallium is in period 4, with much more diffuse orbitals than boron in period 2. With regards to the comparison of heterolytic bonds between B/Ga and Br, the 2p-4p orbital overlap (B-Br bond) is much greater than the 4p-4p orbital overlap (Ga-Br bond) owing to the aforementioned orbital size, hence the Ga-Br bonds are weaker. B and Ga are roughly similar in Pauling electronegativities, with only a difference of 0.23. In both cases, the bromine substituents are more electronegative and as a result the electron density is expected to lie closer to the bromine atoms. The effect of this on bond length is to pull the bromine atom closer to the central atom, althuogh again this effect is not strong enough to overcome sheer orbital size of gallium.

In the most general of terms, a bond is known to contain a focus of electron density between two atoms. This is then categorized into strong bonds (e.g, ionic or covalent) or weak bonds (e.g, hydrogen bonding) and further still: e.g, 2c-3e bonds.It was observed when optimizing some molecules in this section of the experiment that GaussView will sometimes omit physical bonds between atoms where we perceive them to exist. Presumably this is because GaussView characterizes a bond based on numerical distance alone. Of course, this a very objective take on the formation of a bond, whereas in reality it requires a more delicate approach invoking molecular orbital theory.

Frequency Analysis

The purpose of a frequency analysis is to determine whether the stationary point located by an optimization is a minimum or a saddle point on a potential energy surface. It is a prerequisite that these jobs are run on optimized structures, for the reason that it is the second derivative that will provide this information.[1]Interest lies with the minimum in this case, hence if a frequency analysis produces positive frequencies then the minimum has been found successfully.

We also use the frequency analysis to understand the vibrational modes of a molecule. In the case of a non-linear molecule such as BH3 we expect 3N-6 vibrational modes. Within any frequency analysis section, extracts from the .log files will be included (low frequency sections) to validate the analysis. The so-called 'zero frequencies' represent the movement of the centre of mass of the whole molecule. In such symmetric examples above, this will always be within the central atom. Compared with the real frequencies, the values are tellingly smaller. Normally we look for these zero frequencies to be within ±15.0 cm-1, although we will see later that this may not always be the case.

BH3

| Criterion | Value |

|---|---|

| File Type | .log |

| Calculation Type | FREQ |

| Method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | 6-31G(d,p) |

| Final Energy (au) | -26.6153236 |

| Gradient (au) | 0.000001 |

| Dipole Moment (D) | 0.0000 |

| Point Group | D3h |

| Calculation Time (s) | 126.0 |

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000002 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000001 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000006 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000003 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-1.341762D-11

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

Low frequencies --- -0.7426 -0.4560 -0.0053 10.8514 14.9217 14.9401 Low frequencies --- 1163.0236 1213.2010 1213.2037

GaBr3

| Criterion | Value |

|---|---|

| File Type | .log |

| Calculation Type | FREQ |

| Method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | LANL2DZ |

| Final Energy (au) | -41.7008278 |

| Gradient (au) | 0.0000001 |

| Dipole Moment (D) | 0.0000 |

| Point Group | D3h |

| Calculation Time (s) | 12.5 |

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000000 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000000 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000002 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000001 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-6.142863D-13

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

Low frequencies --- -0.5252 -0.5247 -0.0024 -0.0010 0.0235 1.2010 Low frequencies --- 76.3744 76.3753 99.6982

The digital repository can be found on DSpace.

Analysis

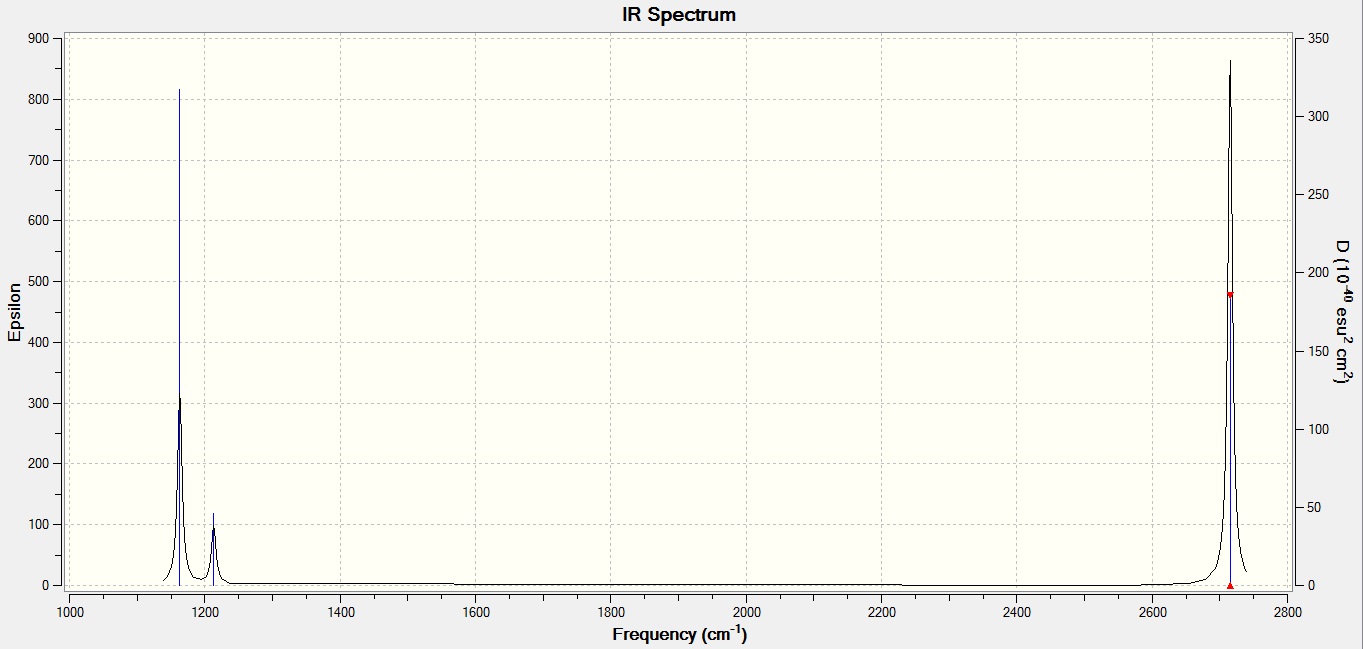

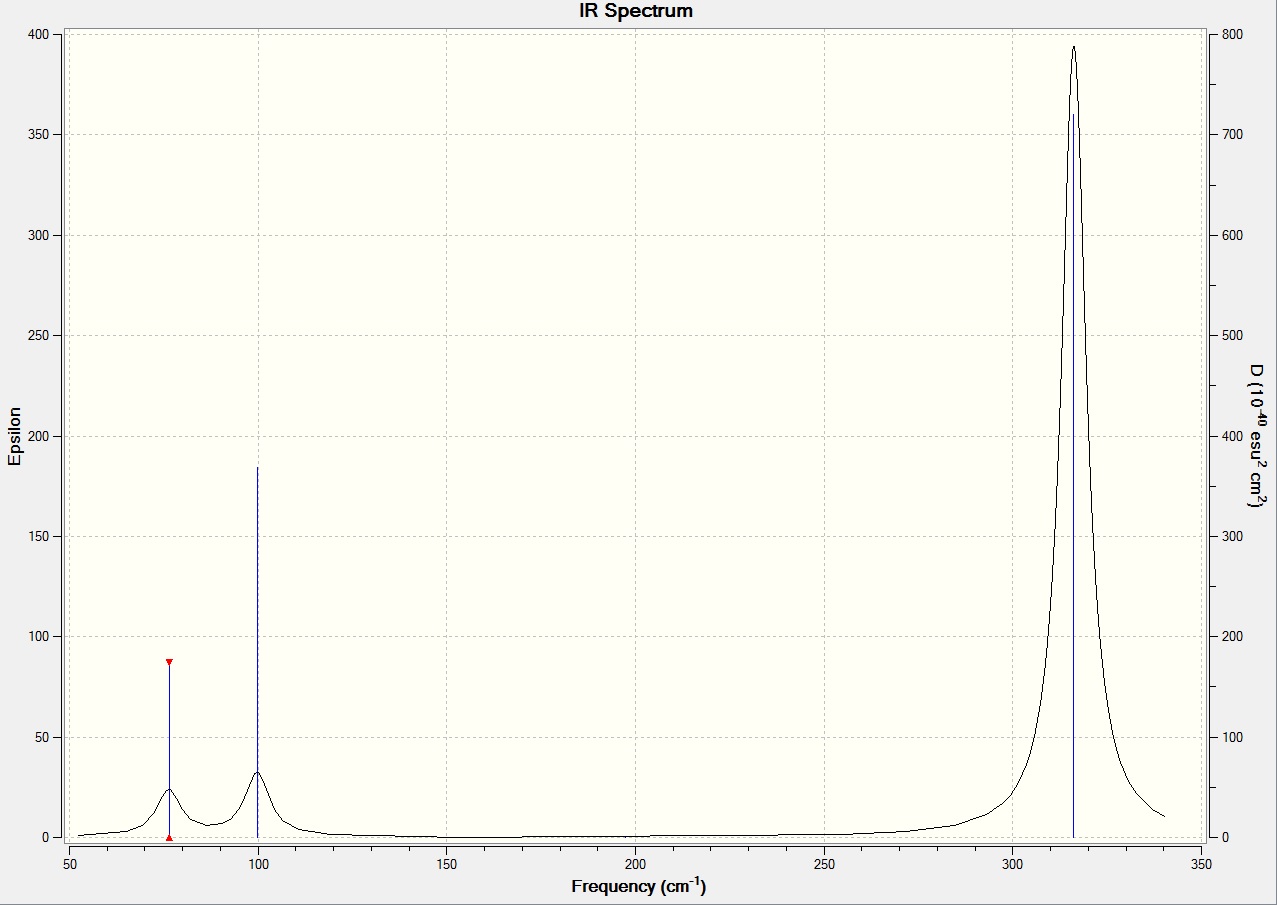

| Mode | BH3 frequency (cm-1) | GaBr3 frequency (cm-1) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1163 | 76 |

| 2 | 1213 | 76 |

| 3 | 1213 | 100 |

| 4 | 2582 | 197 |

| 5 | 2715 | 316 |

| 6 | 2715 | 316 |

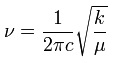

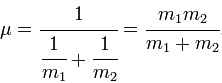

It is clear from the table above that the stretching frequencies of BH3 and GaBr3 differ greatly. This is a major indication of the bond strengths within the two molecules. It is known that a high stretching frequency corresponds to a high bond strength. In the equation displaying the harmonic oscillator model, the spring constant k is directly proportional to bond strength. With different diatomic bonds giving rise to different spring constants, this will be a factor in affecting the stretching frequency. Another factor in determining the stretching frequency is the reduced mass, given by the symbol μ. The heavy gallium and bromine atoms lead to a reduced mass approximately 37 times larger than that of BH3. The inverse proportion of vibrational frequency on reduced mass explains their position on the predicted IR spectrum.

Looking at the table above, the lowest energy degenerate modes have been rearranged upon substitution of the substituents (modes 2 & 3 for BH3 correspond to modes 1 & 2 for GaBr3).

The spectra themselves take a similar shape, with 2 groups of 3 modes (1-3 and 4-6) in different regions of the spectrum. This form differs between spectra in the fact that there is only one peak of considerable intensity in GaBr3 at 316 cm-1 as opposed to two strong intensity peaks in the BH3 spectrum, at 1163 and 2715 cm-1. With both molecules belonging to the D3h point group, the same vibrational modes are exhibited, causing the same absence of certain peaks in the spectra. Two pairs of modes are degenerate and hence contribute to the same signal in the spectrum, reducing the expected number of peaks to be 4. Furthermore, as shown above, mode 4 is a totally symmetric action which does not generate a change in dipole moment and hence is not IR-active.

The groups of modes, as mentioned earlier, originate from the type of vibrational mode produced. The high energy modes (4-6) resemble frequencies of stretching modes whereas the lower energy modes (1-3) represent bending modes. The stretching modes are higher in energy because of the energy input required to change bond lengths. As modelled by the Lenard-Jones potential, moving the nuclei of two atoms closer than their equilibrium distance drastically increases the energy of the molecule. In stark comparison, bending modes require bond angles to be changed, causing less energetically-demanding repulsive actions.

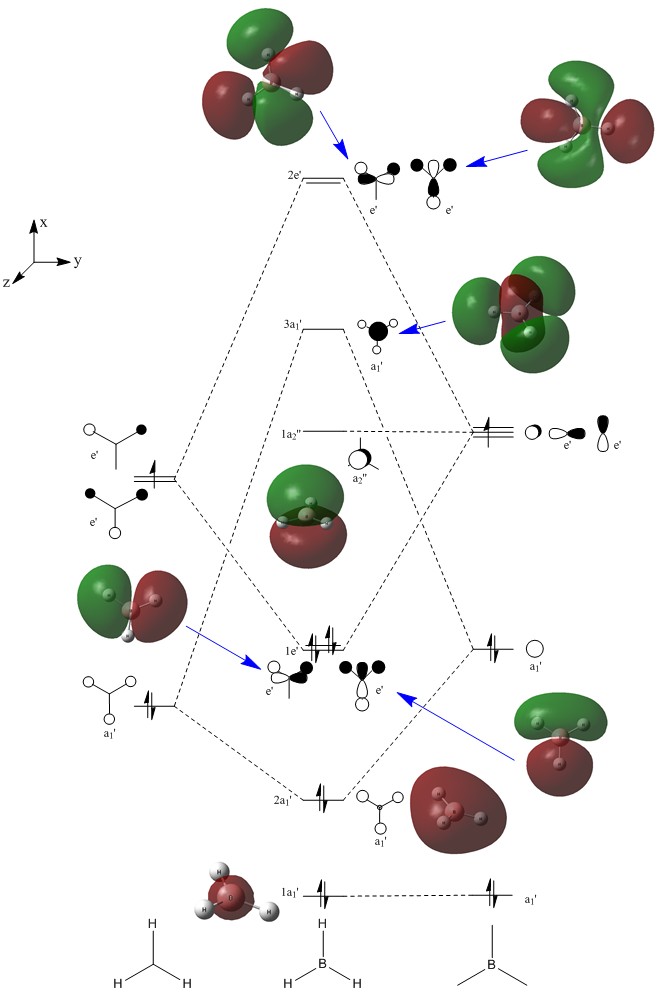

BH3 MO Diagram

For this part of the experiment, an energy calculation was generated in order to analyse both the MO and NBO outputs.

| Criterion | Value |

|---|---|

| File Type | .log |

| Calculation Type | SP |

| Method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | 6-31G(d,p) |

| Final Energy (au) | -26.6153236 |

| Gradient (au) | |

| Dipole Moment (D) | 0.0000 |

| Point Group | D3h |

| Calculation Time (s) | 6.2 |

The digital repository for these calculations can be found on DSpace.

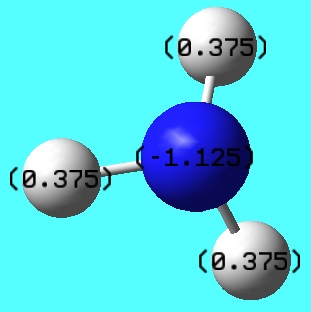

NBO Analysis of NH3

| Criterion | Value |

|---|---|

| File Type | .log |

| Calculation Type | FOPT |

| Method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | 6-31G(d,p) |

| Final Energy (au) | -56.5577687 |

| Gradient (au) | 0.00000095 |

| Dipole Moment (D) | 1.847 |

| Point Group | C1 |

| Calculation Time (s) | 17.0 |

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000002 0.000015 YES

RMS Force 0.000001 0.000010 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000005 0.000060 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000003 0.000040 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-9.687922D-12

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

| Criterion | Value |

|---|---|

| File Type | .log |

| Calculation Type | FREQ |

| Method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | 6-31G(d,p) |

| Final Energy (au) | -56.5577687 |

| Gradient (au) | 0.00000095 |

| Dipole Moment (D) | 1.847 |

| Point Group | C1 |

| Calculation Time (s) | 10.0 |

Low frequencies --- -6.5478 -4.7624 -0.0008 0.0001 0.0007 1.3376 Low frequencies --- 1089.3505 1693.9257 1693.9298

DSpace link for MO analysis of NH3.

| Criterion | Value |

|---|---|

| File Type | .log |

| Calculation Type | SP |

| Method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | 6-31G(d,p) |

| Final Energy (au) | -56.5577687 |

| Gradient (au) | |

| Dipole Moment (D) | 1.847 |

| Point Group | C1 |

| Calculation Time (s) | 9.4 |

As one would predict; the nitrogen atom has a large negative charge relative to the hydrogen atoms and the sum of all NBO charges is 0, confirming the neutrality of NH3 as a molecule.

Association Energy of NH3 and BH3

By performing the same calculations on NH3BH3, enough information would be provided to calculate the predicted association energy of ammonia-borane.

| Criterion | Value |

|---|---|

| File Type | .log |

| Calculation Type | FOPT |

| Method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | 6-31G(d,p) |

| Final Energy (au) | -83.2246891 |

| Gradient (au) | 0.0000013 |

| Dipole Moment (D) | 5.565 |

| Point Group | C1 |

| Calculation Time (s) | 58.0 |

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000002 0.000015 YES

RMS Force 0.000001 0.000010 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000023 0.000060 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000010 0.000040 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-8.987775D-11

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

| Criterion | Value |

|---|---|

| File Type | .log |

| Calculation Type | FREQ |

| Method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | 6-31G(d,p) |

| Final Energy (au) | -83.2246891 |

| Gradient (au) | 0.0000013 |

| Dipole Moment (D) | 5.565 |

| Point Group | C1 |

| Calculation Time (s) | 31.0 |

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000004 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000001 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000022 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000010 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-1.130623D-10

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

Low frequencies --- -3.2536 -2.7238 0.0005 0.0006 0.0008 3.6951 Low frequencies --- 263.3396 632.9623 638.4414

As mentioned earlier in the wiki, it is imperative to use the same basis set and method in calculations that later will be compared. For this reason, new calculations were performed on BH3. These are shown below.

| Criterion | Value |

|---|---|

| File Type | .log |

| Calculation Type | FOPT |

| Method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | 6-31G(d,p) |

| Final Energy (au) | -26.6153236 |

| Gradient (au) | 0.0000022 |

| Dipole Moment (D) | 0.0000 |

| Point Group | CS |

| Calculation Time (s) | 8.0 |

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000004 0.000015 YES

RMS Force 0.000003 0.000010 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000017 0.000060 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000011 0.000040 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-1.052583D-10

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

| Criterion | Value |

|---|---|

| File Type | .log |

| Calculation Type | FREQ |

| Method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | 6-31G(d,p) |

| Final Energy (au) | -26.6153236 |

| Gradient (au) | 0.0000021 |

| Dipole Moment (D) | 0.0000 |

| Point Group | D3h |

| Calculation Time (s) | 8.0 |

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000004 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000002 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000017 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000008 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-1.061412D-10

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

Low frequencies --- -16.0971 -13.0465 -5.4492 -0.0007 -0.0007 -0.0004 Low frequencies --- 1162.9725 1213.1390 1213.1563

A frequency analysis was performed where all frequencies were positive (ensuring an energy minimum had been found).

| Molecule | Energy (au) |

|---|---|

| BH3 | -26.6153236 |

| NH3 | -56.5577687 |

| NH3BH3 | -83.2246891 |

Energy difference in au is calculated to be -0.0515968. Once converted to kJ/mol the value for the association energy is -135.4416. Alternatively, the bond dissociation energy is found to be roughly 135.4 kJ/mol.

Y3C: Ionic Liquids

Introduction

Using the skillset developed in the compulsory section, the task now was to carry out similar calculations on a range of cations. The influence of functional groups will also be investigated further. The interest in the properties of various cations arises from the new field of research into ionic liquids. By being able to tailor a unique cation/anion combination, the respective properties can be present in the solvent. The following computational processes were carried out as a route into predicting the properties of certain cations. NB: For this part of the assignment the keywords "nosymm", "int=ultrafine" & "scf=conver=9" were compiled into the calculation basis set.

Onium Cations

Optimization and Frequency Analysis

[N(CH3)4]+

[N(CH)] |

| Criterion | Value |

|---|---|

| File Type | .log |

| Calculation Type | FOPT |

| Method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | 6-31G(d,p) |

| Final Energy (au) | -214.1812735 |

| Charge | +1 |

| Spin | Singlet |

| Gradient (au) | 0.0000165 |

| Dipole Moment (D) | 11.4150 |

| Point Group | C1 |

| Calculation Time (s) | 1873.5 |

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000041 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000017 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.001572 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000546 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-8.920427D-08

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

As demonstrated from the previous section, the four 'YES' values show that the optimization has converged to a minimum.

| Criterion | Value |

|---|---|

| File Type | .log |

| Calculation Type | FREQ |

| Method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | 6-31G(d,p) |

| Final Energy (au) | -214.1812735 |

| Charge | +1 |

| Spin | Singlet |

| Gradient (au) | 0.0000165 |

| Dipole Moment (D) | 12.913 |

| Point Group | C1 |

| Calculation Time (s) | 1090.9 |

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000038 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000016 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.001538 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000593 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-7.797056D-08

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

Low frequencies --- -4.0626 -0.0006 0.0008 0.0009 1.1629 4.5554 Low frequencies --- 183.1164 288.7045 289.0634

The low frequencies above are shown to coincide well within the ±20-30 cm-1 desired range. All real frequencies are positive, confirming that the structure is a minimum and not a transition state.

[P(CH3)4]+

[N(CH)] |

| Criterion | Value |

|---|---|

| File Type | .log |

| Calculation Type | FOPT |

| Method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | 6-31G(d,p) |

| Final Energy (au) | -500.8270111 |

| Charge | +1 |

| Spin | Singlet |

| Gradient (au) | 0.000021 |

| Dipole Moment (D) | 5.4458 |

| Point Group | C1 |

| Calculation Time (s) | 973.0 |

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000081 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000010 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000665 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000178 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-1.615076D-08

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

After quite an obstacle, finally [P(CH3)4]+ was correctly optimized to the global minimum of the potential energy surface. Problems arose from previous frequency analyses, when a 'low frequency' of -179 cm-1 was generated (here is an example .log file for these failed processes). This negative frequency, also referred to as an imaginary frequency, proved that the optimized structure was not a minimum and was rather a transition state. Because this imaginary frequency is not large in magnitude, it suggested that only a small change in geometry was required somewhere in the molecule.[ref book] An investigation into the vibrational mode causing this frequency indicated that the orientation of hydrogens in two of the methyl groups were not optimal. In these substituents the dihedral angles between C-H and P-C' bonds were found to be 0.1°, demonstrating a blatantly unfavourable eclipsed conformation. Here is the jmol of the transition state. Despite this detour, the molecule was altered and successfully optimized, as shown by both the Item table above and the frequency extract below.

| Criterion | Value |

|---|---|

| File Type | .log |

| Calculation Type | FREQ |

| Method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | 6-31G(d,p) |

| Final Energy (au) | -500.8270111 |

| Charge | +1 |

| Spin | Singlet |

| Gradient (au) | 0.000021 |

| Dipole Moment (D) | 5.4458 |

| Point Group | C1 |

| Calculation Time (s) | 550.0 |

Low frequencies --- -6.1275 -2.1107 0.0009 0.0024 0.0032 7.2925 Low frequencies --- 156.3580 192.1032 192.2938

[S(CH3)3]+

[N(CH)] |

The cation [S(CH3)3]+, in contrast to the previous two cations, only accommodates 3 methyl substituents. This results in its trigonal pyramidal geometry.

| Criterion | Value |

|---|---|

| File Type | .log |

| Calculation Type | FOPT |

| Method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | 6-31G(d,p) |

| Final Energy (au) | -517.6832735 |

| Charge | +1 |

| Spin | Singlet |

| Gradient (au) | 0.0001097 |

| Dipole Moment (D) | 8.18 |

| Point Group | C1 |

| Calculation Time (s) | 377.1 |

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000109 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000055 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.001101 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000477 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-7.149391D-07

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

The Item table above shows that the optimization has located a stationary point within the calculation thresholds.

| Criterion | Value |

|---|---|

| File Type | .log |

| Calculation Type | FREQ |

| Method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | 6-31G(d,p) |

| Final Energy (au) | -517.6832735 |

| Charge | +1 |

| Spin | Singlet |

| Gradient (au) | 0.0001096 |

| Dipole Moment (D) | 8.18 |

| Point Group | C1 |

| Calculation Time (s) | 513.8 |

Low frequencies --- -7.7600 -4.2240 -0.0044 -0.0010 0.0039 10.5434 Low frequencies --- 162.8679 200.1490 200.7812

Suitable 'low frequencies' are shown in the extract above, confirming the optimized structure is indeed the minimum.

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000302 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000110 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.001365 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000615 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-9.205098D-07

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

Comparison of Cations

| Bond Length of C-Y (Å) | Bond Length of C-H (Å) | Bond Angle of C-Y-C | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [N(CH3)4]+ | [P(CH3)4]+ | [S(CH3)3]+ | [N(CH3)4]+ | [P(CH3)4]+ | [S(CH3)3]+ | [N(CH3)4]+ | [P(CH3)4]+ | [S(CH3)3]+ |

| 1.51 | 1.82 | 1.82 | 1.09 | 1.09 | 1.09 | 109.5° | 109.5° | 102.7° |

As mentioned earlier, both tetra-coordinated structures [N(CH3)4]+ and [P(CH3)4]+ adopt tetrahedral geometries whereas [S(CH3)3]+ adopts a trigonal pyramidal structure. Tetrahedral geometries are expected in most covalent structures with a tetra-substituted central atom. It should be mentioned that [S(CH3)3]+ adopts a tetrahedral pseudo-structure, but in reality one of the bonds is occupied by a lone pair on the S atom. The presence of a lone pair in this cation would also rationalise why the C-Y-C bond angle is lower than the comparative cations. The electronically demanding lone pair repels the methyl groups, hence reducing the bond angle to 102.7°.

In terms of C-Y bond length, the results agree with what is expected in the fact C-N is the shortest bond. Both N and C are in the same period, so 2p-2p orbital overlap is more favourable than 2p-3p overlap in a C-P or C-S bond. This difference in orbital combination, and hence bond strength, results in different lengths of bond. We might expect the C-P bond to be longest because P is the largest central heteroatom in the study. The increased Zeff of S results in a smaller atomic radius and in theory we would recognise this from a shorter bond length.

The C-H bond distances do not vary with change of the central heteroatom. Invoking arguments of electronegativity, one may expect the C-H bond length to be shorter for [N(CH3)4]+ because nitrogen is the most electronegative of the heteroatoms being compared. Its affinity for electron density could in theory draw electrons from the neighbouring C-H bond, which would shorten this bond length in order to share the remaining electrons more effectively.

Energy Analysis (MO & NBO)

| Criterion | [N(CH3)4]+ | [P(CH3)4]+ | [S(CH3)3]+ |

|---|---|---|---|

| File Type | .log | .log | .log |

| Calculation Type | SP | SP | SP |

| Method | RB3LYP | RB3LYP | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | 6-31G(d,p) | 6-31G(d,p) | 6-31G(d,p) |

| Final Energy (au) | -214.1812735 | -500.8270111 | -517.6832735 |

| Charge | +1 | +1 | +1 |

| Spin | Singlet | Singlet | Singlet |

| Gradient (au) | |||

| Dipole Moment (D) | 12.91 | 5.446 | 8.18 |

| Point Group | C1 | C1 | C1 |

| Calculation Time (s) | 55.0 | 88.8 | 60.2 |

[N(CH3)4]+ MO Representation

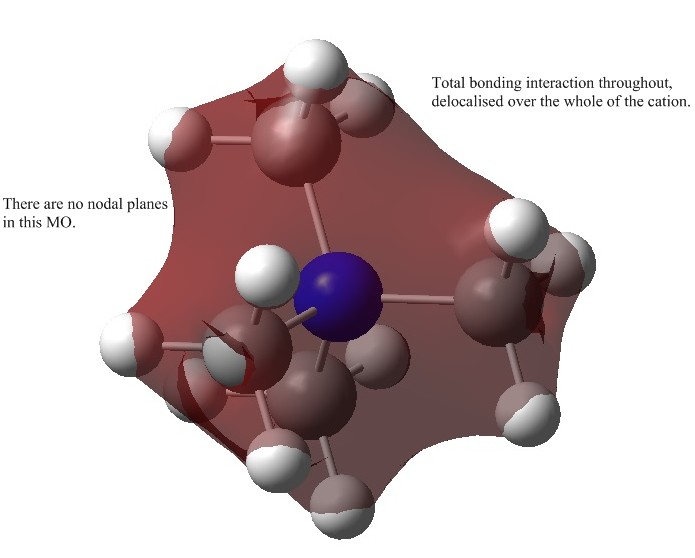

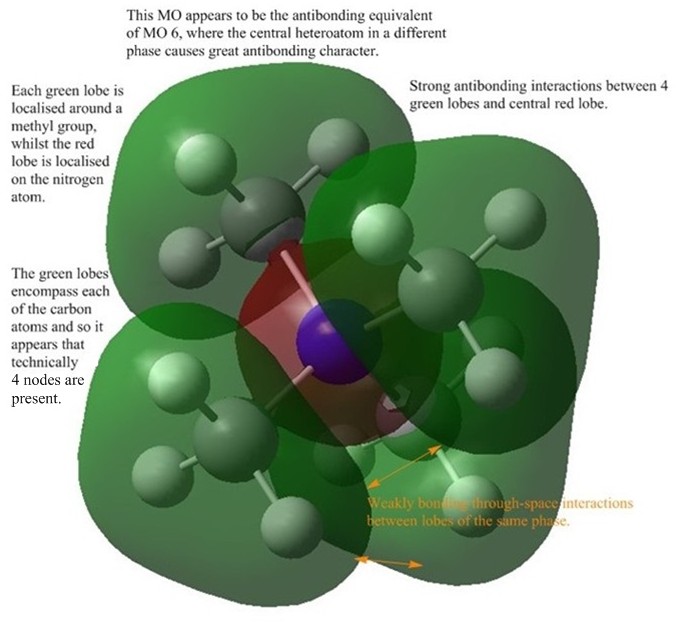

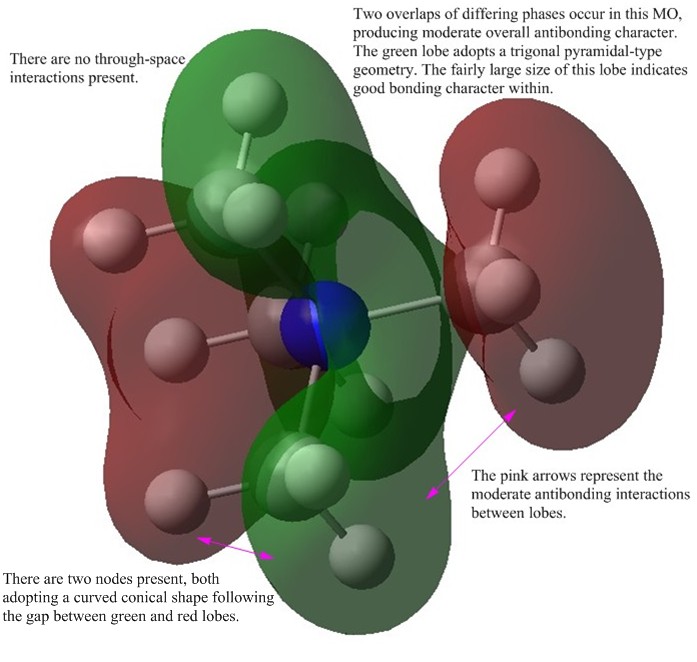

The previously optimized structures underwent energy calculations in order to visualize the MOs. The 21 occupied MOs of [N(CH3)4]+ were created, and 5 analysed further. MOs 1-5 represented core MOs, lying deep in energy, and were not subject to analysis. The 5 investigated MOs are shown below.

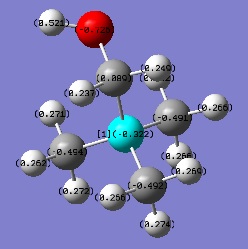

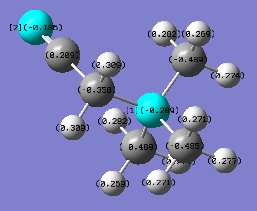

Charge Distribution

| [N(CH3)4]+ | [P(CH3)4]+ | [S(CH3)3]+ |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Cation | C charge | H charge | Y charge | Y electronegativity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [N(CH3)4]+ | -0.483 | 0.269 | -0.295 | 3.04 |

| [P(CH3)4]+ | -1.060 | 0.298 | 1.667 | 2.19 |

| [S(CH3)3]+ | -0.845 | 0.279 | 0.916 | 2.58 |

It is clear from the table above that changing the heteroatom has a drastic effect on the charge distribution within onium cations. When compared with the electronegativity values of each heteroatom, it is no surprise that the nitrogen atom carries the most negative charge. It has the highest affinity for electron density and so will draw electrons from the C-Y bond towards itself. The order of electronegativity fits with the amount of charge held by the remaining heteroatoms. Carbon has a Pauling electronegativity of 2.55 compared to 2.20 of hydrogen and so will always bear the majority of electrons in the C-H bond. This results in a positive charge on each of the hydrogen atoms.

An interesting observation is that the difference between charges on carbon and the heteroatom increases with decreasing electronegativity. A possible reason for this observation could be due to the positive charge (it is a cation after all). In [N(CH3)4]+, it is plausible for only a very small amount of positive charge to be held on the central nitrogen atom because there is excellent orbital overlap with the neighbouring AOs on carbon. The good extent of orbital overlap aids delocalization of the positive charge. Using a similar argument, the orbital overlap is the worst in P-C bonds due to differing orbital size (S-C is slightly better due to an increase in Zeff). This unfavourable combination of orbitals hinders delocalization and hence could explain why the positive charge of the cation appears to be more localised in these two structures.

Bond Contributions

| Cation | C contribution | Y contribution |

|---|---|---|

| [N(CH3)4]+ | 33.65% | 66.35% |

| [P(CH3)4]+ | 59.57% | 40.43% |

| [S(CH3)3]+ | 48.66% | 51.34% |

By analysing the .log file of the energy calculation we are able to discover the contributions to a bond made by each atom. The relative contributions match up with the Pauling electronegativity values stated in the previous section. The bond contribution values above show that the more electronegative atom contributes the most to the bond. This of course relates to basic MO theory, where the AO of the more electronegative atom lies deeper in energy than the opposite AO and therefore contributes the most to the bonding molecular orbital. Similarly, the least electronegative AO contributes more to the anti-bonding MO.

It is difficult to explicitly compare the charge distribution information to the bond contribution information above. The negative charge on the carbon atoms arise from a contribution of 3xC-H bonds, all of which will provide electron density to the carbon atom (as it is the most electronegative atom in the bond). This interfering interaction is not present on the central heteroatom, so to use this information to provide bond contributions is not entirely accurate.

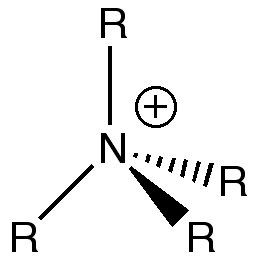

[NR4]+

The traditional depiction shown on the right seems terribly misplaced after recent calculations. If the positive charge was genuinely localized on the nitrogen then we would expect a charge value of +1. The fact it was calculated to be negative demonstrates that the historic illustration is not suited to the actual electron distribution. As we discovered before, with N as the central atom, delocalization with R=alkyl groups is a favoured process owing to good orbital overlap, proved by the small magnitude range of atoms within the [N(CH3)4]+ cation. This incorrect representation should probably be altered to properly represent the positive charge being distributed throughout the whole cation.

Influence of Functional Groups

Optimization and Frequency Analysis

As always, both optimization and frequency jobs were performed to ensure energetic minima had been found. No further discussion of these results is present as the objective was to probe the electronic effects of changing the functionality of a substituent.

[N(CH3)3(CH2OH)]+

| Criterion | Value |

|---|---|

| File Type | .log |

| Calculation Type | FOPT |

| Method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | 6-31G(d,p) |

| Final Energy (au) | -289.3947076 |

| Charge | +1 |

| Spin | Singlet |

| Gradient (au) | 0.000015 |

| Dipole Moment (D) | 11.415 |

| Point Group | C1 |

| Calculation Time (s) | 1223.0 |

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000062 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000012 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.001707 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000379 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-4.359547D-08

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

| Criterion | Value |

|---|---|

| File Type | .log |

| Calculation Type | FREQ |

| Method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | 6-31G(d,p) |

| Final Energy (au) | -289.3947076 |

| Charge | +1 |

| Spin | Singlet |

| Gradient (au) | 0.000015 |

| Dipole Moment (D) | 11.415 |

| Point Group | C1 |

| Calculation Time (s) | 1363.0 |

Low frequencies --- -9.2718 -0.0003 -0.0001 0.0008 3.3894 8.7310 Low frequencies --- 131.5035 213.5522 255.4252

A similar obstacle was encountered (as seen in the optimization of [P(CH3)4]+) where rotation about the C-O bond was required in order to eradicate the possibility of optimizing to a transition state. After overcoming this problem, the optimization had located the correct minimum with confirmation provided by the frequency analysis.

[N(CH3)3(CH2CN)]

| Criterion | Value |

|---|---|

| File Type | .log |

| Calculation Type | FOPT |

| Method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | 6-31G(d,p) |

| Final Energy (au) | -306.3937601 |

| Charge | +1 |

| Spin | Singlet |

| Gradient (au) | 0.000021 |

| Dipole Moment (D) | 10.99 |

| Point Group | C1 |

| Calculation Time (s) | 4941.9 |

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000040 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000012 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.001084 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000232 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-4.130923D-08

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

| Criterion | Value |

|---|---|

| File Type | .log |

| Calculation Type | FREQ |

| Method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | 6-31G(d,p) |

| Final Energy (au) | -306.3937601 |

| Charge | +1 |

| Spin | Singlet |

| Gradient (au) | 0.000021 |

| Dipole Moment (D) | 10.99 |

| Point Group | C1 |

| Calculation Time (s) | 1547.9 |

Low frequencies --- -6.1197 -5.2223 -0.6286 -0.0002 0.0004 0.0005 Low frequencies --- 91.6979 153.8024 210.1897

No imaginary frequencies were discovered, showing once again that the optimization was correct.

Energy Analysis (MO & NBO)

| Criterion | [N(CH3)3(CH2OH)]+ | [N(CH3)3(CH2CN)]+ |

|---|---|---|

| File Type | .log | .log |

| Calculation Type | SP | SP |

| Method | RB3LYP | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | 6-31G(d,p) | 6-31G(d,p) |

| Final Energy (au) | -289.3947076 | -306.3937601 |

| Charge | +1 | +1 |

| Spin | Singlet | Singlet |

| Gradient (au) | ||

| Dipole Moment (D) | 11.42 | 10.99 |

| Point Group | C1 | C1 |

| Calculation Time (s) | 97.0 | 166.4 |

Charge Distribution

The colour-range images are using a scale of -0.8 (bright red) to +0.8 (bright green).

| [N(CH3)3(CH2OH)]+ | [N(CH3)3(CH2CN)]+ |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Cation | Charge of Central N | Charge of Substituted C |

|---|---|---|

| [N(CH3)3(CH2OH)]+ | -0.322 | 0.089 |

| [N(CH3)3(CH2CN)]+ | -0.289 | -0.350 |

| [N(CH3)4]+ | -0.295 | -0.483 |

With the knowledge that -OH is an electron donating group and -CN is an electron withdrawing group, it was expected that the charge distribution would alter relative to the symmetrical [N(CH3)4]+ cation. The introduction of a hydroxyl group feeds electron density into the adjacent C-N bond, resulting in an increase of charge on the N atom compared to the original cation. Somehow, through the electron donation of the -OH group, the substituted carbon atom becomes more positively charged, presumably due to its electronegative neighbouring oxygen atom. With respect to the cyano group, there does not appear to be much effect on the central nitrogen atom. Instead, the carbon of the -CN group is highly positive due to the strong electron withdrawing from the neighbouring nitrogen. The electron withdrawing -CN group also pulls electron density from the substituted carbon atom and from atoms in close proximity. The evidence for this is that the hydrogen atoms bonded to the subtituted carbon are comparatively positive compared to all other methyl hydrogens within the cation, demonstrating an extended electron withdrawing effect.

HOMO/LUMO Region Comparison

The final stage of the assignment was to compare the frontier orbital regions of variants on [N(CH3)4]+. This was done again using an energy calculation.

The computed HOMO and LUMO molecular orbitals of [N(CH3)4]+, [N(CH3)3(CH2OH)]+ and [N(CH3)3(CH2CN)]+ are displayed above. If we compare the images of the respective HOMOs, we can immediately see that the HOMO becomes more localised with the introduction of a -CN or -OH substituent. In [N(CH3)3(CH2CN)]+ the HOMO is most localized, to the extent that the lobes are almost solely on the cyano and substituted methyl group. The character of each HOMO varies too; from what I would interpret as weakly anti-bonding to more strongly anti-bonding in the order of [N(CH3)4)]+<[N(CH3)3)(CH2OH]+<[N(CH3)3)(CH2CN]+ (in this order mainly due to weak through-space bonding interactions from the red lobes in [N(CH3)3)(CH2OH]+). Now comparing these ideas to the relative energies, we can see that both substituted MOs become more anti-bonding in character because of their increase in energy. However, contrary to how I interpreted the structure, it is actually the -OH substituted MO that lies higher in energy. This is viable because the out of phase overlap appears large in that particular MO and must outweight the effect of the weak through-space bonding interactions.

With regards to the LUMO, the overall shape of this molecular orbital stays fairly constant in the comparison. The original LUMO contains 4 nodes, one at each substituent methyl carbon. The number of nodes increases with addition of an -OH group, to what I perceive to be 5 whereas the number nodes remains at 4 if a -CN group is introduced instead. In terms of character, the introduction of prevalent p orbitals from the nitrogen atom suggest an increase in through-space bonding interactions with the rest of the MO. For the -OH substituted cation, the oxygen atom extends the 'red' lobe of the methyl group and hence increases the antibonding interactions with the surrounding green lobe. The qualitative observations agree with the numerical calculations, where the LUMO of [N(CH3)3)(CH2OH]+ increases in energy slightly due to increased antibonding interactions and the LUMO of [N(CH3)3)(CH2CN]+ shows a significant decrease in energy.

In both cases, the introduction of a different substituent decreases the HOMO/LUMO band gap in the order of [N(CH3)4)]+>[N(CH3)3)(CH2OH]+>[N(CH3)3)(CH2CN]+. The difference in energy of the frontier orbitals can obviously affect ΔEHOMO/LUMO which in turn will alter the energy required to excite the cation in question. For example, promotion of an electron from the HOMO to the LUMO will require the least amount of energy in [N(CH3)3)(CH2CN]+. Reversibly, a relaxation from the first excited state to the ground state will produce light with a longer wavelength than that of [N(CH3)3)(CH2OH]+ and [N(CH3)4)]+. This ability to tailor the HOMO/LUMO band gap may be useful in solvent-solute excitation, allowing a quick exchange of ground and excited states to aid reaction rate.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 J. B. Foresman and A. Frisch, Exploring Chemistry with Electronic Structure Methods, Gaussian Inc., Pittsburgh, 2nd edn., 1996

- ↑ K. Kawaguchi, "Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy of the BH3 ν3 band", J. Chem. Phys., 1992, 96, 3411.DOI:10.1063/1.461942

- ↑ B. Reffy, M. Kolonits and M. Hargittai, "Gallium tribromide: molecular geometry of monomer and dimer from gas-phase electron diffraction", J. Mol. Struct., 1998, 445, 139-148.

- ↑ G. Santiso-Quinones and I. Krossing, "Reference Values for the B-X Bond Lengths of BI3 and BBr3", Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem., 2007, 634, 704-707.DOI:10.1002/zaac.200700510

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 S. S. Batsanov, "Van der Waals Radii of Elements", Inorg. Mater., 2001, 37, 871-885.