Rep:Mod:VR813MgO

Introduction

This experiment involves the study of magnesium oxide (MgO) crystals and it's thermal expansion properties by the use of computational methods. By way of investigating the atomic interactions in the MgO crystals, one can calculate the internal energy and the vibrations (phonons) of the crystals. Then, having obtained the vibrational energy levels, thermodynamics can be used to calculate the free energy, in particular the Helmholtz free energy, of the crystal. The study of the vibrational energy levels and the computation of the free energy will allow us to predict how the MgO crystals expand when subjected to heating by use of the harmonic and quasi-harmonic approximations. Subsequently, the MgO crystal will be thermally expanded using the Molecular Dynamics approach. The final objective of this experiment is to calculate thermal expansion coefficients, αV, and compare the thermal expansion of MgO from both the Molecular Dynamics and the Quasi-Harmonic computational methods at a variety of temperature ranges.

Prior to discussing the results of this experiment, it is important to provide a description of the thermal expansion process, the computational methods used and the Programs used to carry out this experiment.

Thermal Expansion

Thermal expansion is the propensity of a material to undergo a change in shape, area and volume when subjected to a change in temperature in a heat transfer process. This behavior can be explained looking at the rise in potential energy of a crystal as temperature rises. This rise in potential energy means that the vibrations of atoms within the crystal occurs at larger amplitudes and thus leads to a larger average intermolecular separation. Finally, it should be noted that the volumetric coefficient of thermal expansion, which is an intrinsic property, gives the change in the volume of a material as the temperature changes (normalised to the sample volume V0) at constant pressure.

Computational Methods

The thermal expansion of the MgO crystal was studied using the quasi-harmonic approximation as well the Molecular Dynamics method.

Quasi-Harmonic Approximation

This is harmonic phonon-based model but it also contains an additional anharmonic factor since the quasi-harmonic approximation is a simple extension from the harmonic phonon model. The quasi-harmonic approximation allows the description of changes in thermal effects to the volume of a material ,e.g. the effects of tempertaure changes to the thermal expansion of a material. The addition of the anharmonic factor changes the potential energy surface from a quadratic function (i.e. the harmonic model) to a potential energy surface that resembles closely the Lennard-Jones potential. The need for the use of the quasi-harmonic approximation to study thermal expansion can be immediately seen as the simple harmonic phonon model predicts that all forces between atoms are purely harmonic. However the harmonic model is so simple that it is inadequate to explain thermal expansion as the model predicts that the equilibrium distance between atoms doesn't change with temperature. Hence, in the quasi-harmonic approximation, the addition of the anharmonic factor leads to the change in the intermolecular distance with changes in temperature. The final outcome of this is that the quasi-harmonic approximation allows the explanation of thermal expansion. It should be noted that the introduction of the anharmonic terms leads to the introduction of phonon frequencies which are volume dependent [1].

Furthermore, as mentioned earlier, this model is based on phonons which are the elementary vibrations in a crystal lattice and these phonons have particle-like properties (i.e. very similar to the concept of photons). The quasi-harmonic approximation states that the phonon oscillates throughout the crystal structure in one dimension. The energy a molecule has is related to the amplitude of the vibrational mode and this total energy is calculated by computing the energy over all the vibrational modes (over all the energy bands) of the crystal.

Molecular Dynamics

Molecular Dynamics (MD) performs a more classical computer simulation based upon Newton's laws of motion. In particular, the Molecular Dynamics approach allows the system to develop with time in accordance and agreement with Newton's Second Law:

The use of Newton's Second Law allows the trajectories of atoms to be computed and subsequently allows time averages of thermodynamic properties to be computed. The Molecular Dynamics technique carries out the simulations by emulating the actual vibrations of the molecules within the crystal and this allows movement in three dimensions.

In the MD approach, atoms interact for a fixed time and thus the trajectories can be computed by solving Newton's Laws of Motion for a system containing interacting particles; the solution cannot be obtained analytically but rather by numerical methods especially for systems containing many particles. Overall, by calculation of the trajectories of the atoms in a system, the MD technique allows for the computation of the thermodynamic properties of a system from various time-average calculations.

Software and Programs

In summary, the RedHat Linux, DLVisualize (DLV) and General Utility Lattice Program (GULP) programs were used to model and run calculations on the MgO crystal lattice.

RedHat Linux is the operating system of choice for this experiment as Linux provides an excellent environment which has the capability of running complex numerical simulations such as those needed when modelling the thermal properties of an MgO crystal. DLV is a visualizer which allows the modelling of structures such as MgO. It is a graphical user interface which allows for easy studying of crystal structures, e.g. MgO, and it allows an understanding of how these crystal structures change when the environment placed upon it is changed. In this experiment, DLV will be used to understand the effects on the MgO structure when the temperature of the environment is changed. Finally, GULP is a program for performing a great range of types of simulations on materials using boundary conditions. It permits simulations to be run using lattice dynamics and MD on crystal structures and thus it allows us to gain data such as free energy of a crystal structure and lattice constants by changing the initial conditions of a simulation.

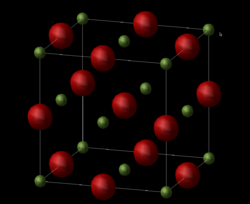

The Primitive and Conventional cell representations of MgO

MgO is an ionic crystal in which electrostatic interaction hold together the doubly charged Magnesium cations and Oxygen anions. Before calculating the internal energy of an MgO crystal, it is necessary to ascertain the crystal structure of MgO and this is done by defining the unit cell of the structure. The MgO crystal structure can be defined using a primitive cell (Figure 1) or a conventional cell (Figure 2) by using the GULP calculations to model the MgO crystal.

Firstly, in the primitive cell (Figure 1), there are 2 atoms (1 Mg atom and 1 O atom) ,in total, enclosed within the cell and it is the simplest possible cell that can be used to describe the full MgO crystal structure. It should be further noted that the cell vectors of this primitive cell have been examined and the table below (Table 1) represents these cell vectors. Moreover, it was found that the primitive cell had a rhombohedron shape with a lattice constant of a =2.9783 Å and internal angles of α = 60 degrees.

| 0.00000 | 2.10597 | 2.10597 |

|---|---|---|

| 2.10597 | 0.00000 | 2.10597 |

| 2.10597 | 2.10597 | 0.00000 |

Apart from the primitive unit cell representation of the MgO crystal, the conventional cell representation can also be used to describe the MgO lattice (Figure 2).

This conventional cell representation of MgO is a face centred cube with a lattice constant of a = 4.212 Å and an internal angle of α = 90 degrees (as expected for a cube). This calculated lattice constant agrees very closely with the literature value of the lattice constant which is a = 4.211 Å [2]. Furthermore, the conventional cell contains 4 Mg atoms and 4 O atoms and so accordingly the volume of the conventional cell is four times larger than that of the primitive unit cell representation of MgO. However, despite the simplicity of the primitive cell representation of MgO, the conventional cell representation is more widely used as it more accurately reflects the symmetry of the ionic structure of MgO. Thus, it is common in literature for any crystallographic studies to use the conventional cell representation of MgO over the primitive cell.

The Internal Energy of an MgO crystal

From the results of the GULP calculation, it is also possible to find out the total energy of the MgO crystal structure due to inter-ionic forces, which takes into account both any short range repulsions and electrostatic potentials by summing over the whole lattice. This energy gives the energy required to separate the ions of the lattice from the equilibrium distance to infinite separation. Overall, the internal energy of the MgO lattice per primitive cell, at 0 K, that was measured is given by:

.

The Phonon Modes of MgO

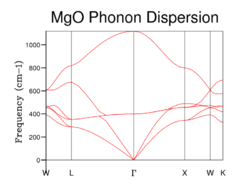

The Phonon Dispersion Curves

The phonon dispersion curve is shown in Fig. 3.

The GULP calculation was carried out to compute the phonon dispersion curve of MgO and the phonons were computed at 50 points along the path defined by the special points W-L-G-W-X-K, known as the conventional path, in k space. These special points along this conventional path reflect the symmetry. Overall the calculation analyses the phonon dispersion along the symmetry points . These symmetry points are used to simplify the vibrations of crystals in 3 dimensions. This is necessary because in 3D, an infinite lattice has an infinite number of vibrations which is difficult to display graphically. Therefore, it is much simpler to assign a symmetry point to every vibration posible of a crystal and so these k-labels (symmetry points) are used.

The phonon dispersion curve (Fig. 3) shows the variation of frequency of vibrations (phonon modes) of the MgO as a function of the k values (i.e. the symmetry points within the lattice). This graph obtained matches exactly with that calculated in literature [3]. It can be seen that there are six different phonon modes as the calculation takes into account of the x, y and z directions. Therefore, there are 2 phonon modes represented in the simulation which is a result of the primitive unit cell of MgO containing 2 atoms. Each axis has associated with it two different types of phonons; the acoustic and optical modes. Thus, there are 3 optical and 3 acoustic modes which represent out-of-phase and in-phase vibrations respectively. The optical vibrational modes (i.e. modes which can interact with IR radiation) are vibrations that occur when atoms move in opposite direction when excited (i.e. out-of-phase vibrations) and this results in the phonons have a non-zero frequency at (i.e. kx=0, ky=0, kz=0). The 3 acoustic vibrational modes occur when atoms move in-phase with one another. As a result of this in-phase vibration, the wavelength of the vibrations tends to infinity and the phonon frequencies are equal to zero at because of the relationship (where k is the wavevector (m -1) and is the wavelength (m)). Lastly, it should be noted that the three acoustic modes can be divided into two groups: transverse and longitudinal modes. There are two transverse modes which pass through the origin and a single longitudinal mode.

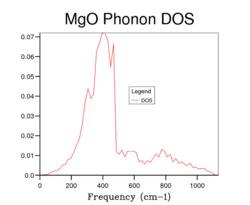

The Phonon Density of States (DOS)

The DOS can be defined as the number of energy states per unit energy at a given energy for an energy band structure. The DOS summarises the dispersion curves and it is an average over all the k-points which yields the number of vibrational modes at each frequency which is known as the density of modes. Then, summing over all of states, each of which are labelled by their k-points, at a given frequency provides the phonon DOS curves.

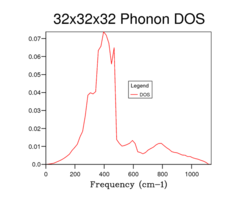

The phonon DOS curve for MgO using a 1x1x1 grid is shown in Fig. 4 and this DOS curve is built by using the results of the phonon dispersion curve shown in Fig. 3. There are 4 peaks which represent the symmetry point L (i.e. k = (1/2, 1/2, 1/2). But, on inspection of the phonon dispersion curve in the previous section, one would expect that there would be 6 distinct peaks in the DOS curve for a 1x1x1 grid. Despite this, 4 peaks are only seen due to the degeneracy of the bands that occur at 288 cm-1 and 352 cm-1. This explains the densities of the peaks in the DOS curve for Fig. 3 as the peaks at 288 cm-1 and 352 cm-1 have double the density compared to the peaks at 676 cm-1 and 819 cm-1 due to this degeneracy. Thus the relative densities of the peaks are 2:2:1:1 for the peaks which corresponds the symmetry point L. Further measurements of the DOS curve for MgO were carried out by increasing the grid size (Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6, Fig. 7) and it can be observed that the DOS curves become increasingly complex as there are more point sampled in the k-space which results in a larger number of peaks in the DOS curves as more and more of the possible vibrations are sampled. However, even though the complexity rises with increasing grid size, the accuracy also increases in the depiction of the DOS curves. The graphs below show the effect of changing the grid size on the DOS curves.

A common feature of all the DOS curves is that the maximum occurs around 400 cm for all grid sizes with decreasing densities for higher frequencies of vibrations. The most important change as one goes from lower to higher grid sizes is that the DOS goes from spiked peaks to a more averaged spectrum. This is related to the discussion above in that the larger grid size means more sampled points in k-space and so the average values for the DOS are more accurate. In order to be able to deduce the best grid size which presents the phonon DOS curve, two factors must be taken into account: the accuracy and the CPU time. As the grid size increases, the accuracy increases but the CPU time is lengthened. Grid sizes smaller than 15x15x15 gives DOS curves which aren't smooth and are rather jagged (i.e. crosses the x axis) and this is due to the fact that too few points are sampled in k-space. On the other hand, the DOS curves are more "smooth" for higher grid sizes than 15x15x15 and so provide more realistic description of the DOS but the shortcoming is the increased CPU time. So it can ascertained that the best grid size to examine the DOS accurately and quickly would be a 15x15x15 grid.

A few other observations can be gathered on inspection of increasing grid sizes. Firstly, the DOS curve resembles more of a bell shaped curve centred at lower frequencies i.e. the DOS curves represent a smooth continuum rather than a set of discrete vibrational peaks. Moreover, comparison of the 15x15x15 and 32x32x32 grid size shows very little difference in the DOS curves. And so this confirms the earlier conclusion that the 15x15x15 grid size is the best grid size to observe the DOS curve due to its high accuracy and short CPU time.

From the Hoffmann article [4], the number of vibrational states is largest when the gradient of the phonon dispersion curve is equal to zero. Another way to state this is that the phonon DOS is inversely proportional to the gradient of the phonon dispersion curve. This is exactly analogous to the energy situation in which the energy DOS is largest at the flattest regions of the energy dispersion curve and this is given by the following relation (which shows the inverse proportionality):

. (where m is the number of energy states and E is the energy).

A similar analysis can be completed when treating other materials such as CaO, Lithium and zeolites.

In order to understand the optimal grid sizes for these materials, we need to remember the relationship between the lattice constant in real space and in reciprocal space which is given by:

(where a* is the lattice constant in reciprocal space and a is the lattice constant in real space).

Thus for Lithium, which has a small lattice constant in real space and thus a large lattice constant in reciprocal space, and so this larger cell for the Lithium metal in reciprocal space means that more points need to be sampled within k-space ,i.e. more k-points must be sampled, in order to get a more accurate result for both the phonon dispersion curves, phonon DOS and the computation of the free energy. So we would need larger grid sizes in order to satisfy the need to sample more k-points within reciprocal space for Lithium. As confirmation of the large lattice constant in reciprocal space, the lattice constant of Lithium in real space is given by 3.51 Å [5] which is much smaller than the lattice constant for MgO stated earlier and so agrees with the suggestion that a larger grid size would be needed, compared to MgO, to attain accurate results.

Moving onto zeolites, and in particular Faujasite, which has a very large lattice constant in real space results in a small cell in reciprocal space. And so, it is only necessary to sample a few points in k-space to obtain accurate results. Therefore, the grid size does not need to be large as the k-points that are sampled will be in close proximity of one another. Thus, any k-points that are omitted during the sampling process won't be detrimental to the accuracy of the results as they don't add any vital information to the phonon dispersion curve, phonon DOS or the free energy computation. So overall, the potential shortcoming of using small grid sizes for MgO (i.e. the inaccuracy in the phonon DOS as was shown by Figures 4. and 5.) does not apply to Faujasite as there is no benefit to using a larger grid size. Moreover, the use of a larger grid size would take up more time due to more calculations required. All of the above can be confirmed by comparing the real space lattice constant of Faujasite, which is 24.45 Å [6], which is much larger than MgO (4.211 Å [2]) and so the Faujasite has a smaller k-space lattice constant and so confirms the observation that fewer k-points need to be sampled as it has a smaller cell size in reciprocal space.

Lastly, a phonon dispersion curve and phonon DOS computation can be done for another group 2 metal oxide which is calcium oxide, CaO. Both CaO and MgO are group 2 metal oxides and so one would expect the lattice constants to be vaguely similar in real space and thus nearly equivalent in reciprocal space. As a result of calcium and magnesium being in group 2, there will be plenty of similarities in properties and structure. Consequently, the similarity in lattice cell size in reciprocal space means that the same grid size that provided accurate results for MgO for the phonon DOS will be the same for CaO. Thus, a 15x15x15 grid size will produce accurate results for the phonon DOS for CaO too. Once again, this similarity can be confirmed by comparison of the lattice constants which are 4.8 Å [7] and 4.211 [2] for CaO and MgO. This close match in lattice constants in real space and, thus, reciprocal space shows that an identical grid size will give an accurate phonon DOS computation for both.

Computing the Free Energy

| Grid Size | Helmholtz Free Energy / eV | Accuracy / eV |

| 1x1x1 | -40.9303 | 0.1 |

| 2x2x2 | -40.9266 | 0.1 |

| 3x3x3 | -40.9264 | 0.001 |

| 4x4x4 | -40.9265 | 0.0005 |

| 8x8x8 | -40.9265 | 0.0005 |

| 16x16x16 | -40.9265 | 0.0001 |

| 32x32x32 | -40.9265 | N/A |

The quasi-harmonic approximation was used to calculate the free energy of MgO by summing over all of the vibrational modes of the lattice. The computations were carried out at 300 K. The results are displayed in Table 2.

There are many observations one can make upon inspection of the results. Firstly, an identical observation that was seen for the effect of grid sizes on the accuracy of the phonon DOS curves also applies here. As the grid size increases, the accuracy of the free energy computation increases but the shortcoming is that the CPU time increases for the same reasons described in the phonon DOS discussion. This increasing accuracy with increasing grid size can be explained by the fact that more k-points are sampled with increasing grid size and so the more accurate the value of the Helmholtz free energy. Other than the simplistic observations, one can also see that increasing the grid size makes the computations for the free energy less negative i.e. the free energy increases with increasing grid size. This can be explained by looking at the Boltzmann equation and the Helmholtz free energy, F, as well as the equation relating internal energy, U, to the volume, V.

(where U is the internal energy, P is the pressure, V is the volume and H is the enthalpy).

(where S is the entropy, kB is the Boltzmann constant and W is the number of possible microstates).

(where F is the Helmholtz free energy, U is the internal energy, T is the temperature and S is the entropy).

Firstly in terms of thermodynamics, an increasing grid sizes can loosely be translated to an increasing volume and so increasing the grid size increases the magnitude of the PV term which makes the internal energy become less positive i.e. decrease. Next, concentrating on the Boltzmann equation for the entropy, one can state that increasing the grid size also makes the entropy increase as the increasing grid size contributes to the increase in microstates available for the system and so higher entropy. Overall, a decreasing internal energy and an increasing entropy serve to decrease the Helmholtz free energy, F, and so makes it lower in value.

And so, having observe the data in table 2, one can come to a conclusion that the best grid size for computing the free energy of MgO is the 16x16x16 grid as it gives the greatest accuracy.

Thermal Expansion of MgO

In this section, the structure of MgO was optimised with respect to the free energy at a variety of temperatures. In this case, the temperature was varied between 0 - 1000 K. The free energy was then computed using the quasi-harmonic approximation. In the following section, the thermal expansion of MgO was further computed using the Molecular Dynamics simulation. Finally, the results of the quasi-harmonic approximation and the Molecular Dynamics simulation were compared and the thermal expansion coefficients were calculated in both cases too.

In brief, the thermal expansion coefficient gives a mathematical description of how the size and volume of an object changes with changing temperature at constant pressure i.e. the small change in volume is measured per unit change in temperature (in Kelvin). Since in this study, a three-dimensional MgO structure is studied, the volumetric thermal expansion coefficient will be studied. However, it is also possible to calculate the linear (1D) and area (2D) thermal expansion coefficients depending on the dimensions of the structure under investigation. It should be noted that the coefficient of thermal expansion should be standardized by dividing by the initial length, area or volume of the material depending on the dimensionality.

The equation for the volumetric coefficient of thermal expansion, αV, is given by:

- where αV is the volumetric coefficient of thermal expansion, V is the (initial) volume, ∂V is the partial derivative of the volume, ∂T is the partial derivative of temperature (at constant pressure)

Thus, from this equation, a comparison of various solids can be made. A straightforward conclusion from this equation is that the higher the thermal expansion coefficients, the greater the rate of thermal expansion. In the case of MgO, it has strong ionic bonding within its structure and so one would expect for it to have a rather low volumetric thermal expansion coefficient.

The Thermal Expansion of MgO using the Quasi-Harmonic approximation

When studying Graph 2, which shows the variation of the free energy of the MgO with temperature using the Quasi-Harmonic approximation, one can see that free energy becomes increasingly negative with increasing temperature in a quadratic relationship. This relationship can be understood by considering the Gibb's free energy.

Overall, this explains the increasingly negative Gibbs free energy with increasing temperature. The increasing temperature increases the entropic contribution to the free energy and at very large temperatures, the entropy terms dominates. The change in the free energy is proportional to the negative of the temperature change i.e. an positive temperature changes corresponds to a negative free energy change which is what is seen in Graph 2. It can also be shown that the gradient of the curve is given by: . So the gradient of the curve is given by the negative of the entropy value. Moreover, it is known that the entropy increases with increasing temperature and so at higher temperatures, the entropy value increases rapidly. Therefore, this explains the increasing steepness in the negative gradient at higher temperatures since the entropy also increases and so the gradient becomes steeper.

Observation of Graph 3, which shows how the lattice constant of MgO varies with temperature, leads to an opposing conclusion i.e. the lattice constant increases with temperature. In other words, both the dimensions of the cell in the primitive lattice and the conventional cell representation increases with temperature. This may be explained by considering the phonons as at higher and higher temperatures, the amplitude of the vibrations within the crystal increases. This yields in an increased average separation between the ions in the lattice due to this high amplitude phonons. Thus, it can be confirmed that the thermal expansion of MgO does occur. Moreover, since the average position between ions increases and the lattice constant corresponds to these average positions of the ions, it can be concluded that the lattice constant increases with temperature.

Computing the Thermal Expansion Coefficients and the Main Approximations

The Linear and Volumetric thermal expansion coefficients are calculated below using the quasi-harmonic approximations. The results of the calculation are provided at the bottom of the page in the "Calculations" section.

The Linear Thermal Expansion Coefficient is calculated to be K-1. The Volumetric Thermal Expansion Coefficient is calculated to be K-1.

From the thermal coefficients calculated above, it can be seen that the relationship, = , is approximately satisfied. The fact that this volumetric thermal expansion coefficiet is three times the linear coefficient shows that MgO is an isotropic material [8]. The actual ratio of the volumetric and linear thermal coefficients calculated is = and so the volumetric thermal expansion coefficient is not exactly 3 times that of the linear thermal expansion coefficient due to the breakdown of the simplicity of the quasi-harmonic approximation.

The literature value for the linear thermal expansion coefficient for MgO, at 300 K, is given by K-1 [9]. This is sufficiently different from the value of the linear thermal expansion coefficient calculated which could be due to the breakdown of the simplicity of the anharmonicity of the model implemented in the program. Moreover, the difference between the calculated and literature value arise from the fact that the expansion coefficients were measured over different temperature ranges (i.e. the calculated linear thermal expansion coefficient was calculated in the range 0-1000 K whilst the literature value is given at a temperature range 0-300 K). However, when considering the relationship of the Gibb's Free energy with temperature, G = H - TS, one would expect the Gibb's Free energy to decrease linearly with increasing temperature. This linear relationship occurs most closely in the 0-300 K region from Graph 2. Past 300 K, the data deviates from a linear fit. Thus, one can imply that that anharmonicity introduced in the model has led to this deviation and it would possibly have been more reliable to calculate the linear thermal expansion coefficient from the 0-300 K temperature range.

The literature value for the volumetric thermal expansion coefficient for MgO, at 300 K, is K-1 [10]. Just as for the linear thermal expansion coefficient, the literature value for the volumetric thermal expansion coefficient is larger than the value of the calculated volumetric thermal expansion coefficient. The reasoning behind this is identical to that explained above for the linear thermal expansion coefficient.

Despite this, there is still a good correlation between the calculated values and the literature values of both thermal expansion coefficients.

In terms of the main approximations implemented in these calculations, the most important one is that of the anharmonicity of the model which was described in depth in the introduction. This quasi-harmonic (i.e. not perfectly harmonic due to the anharmonic implementation into the model) approximation limits the accuracy of the data which is shown above in the comparison with the literature values. Overall, the anharmonic contribution becomes more significant at higher and higher temperatures which reduces the accuracy of the model. As a result, the quasi-harmonic model breaks down in terms of accuracy and reliability at higher temperatures but it still remains an excellent model at lower temperatures (i.e. near the range 0-300 K).

Another major approximation used was the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, in which the nuclear and electronic wavefunctions are separated, which would have further limited the accuracy of the data produced. Lastly, electron-electron interactions are assumed to be ignored.

Further discussion on the quasi-harmonic approximation to calculate the thermal expansion coefficients

There is further speculative discussion that can be done with respect to the quasi-harmonic model in the calculations of the thermal expansion coefficients.

1. What is the physical origin of thermal expansion?

To summarize prior discussion pertaining to this point, it is important to note that as temperatures rise, there would be increased vibrations of the ions in the lattice and larger phonons therefore. Thermal expansion follows simply from this as the increased vibrations mean that the phonons have larger amplitudes and so on average, the ions would be further apart at higher temperatures. The fact that the average distance between ions in the cell and the lattice increases at high temperatures means that thermal expansion is occurring. All of this can be seen in Graph 3. Larger amplitude vibrations means

2. What happens when the temperatures approaches the melting point of MgO and how do well the phonon modes describe the motion of the ions at this temperature?

Firstly, the melting point of MgO is 2852 °C. As the temperature approaches this value, when using the quasi-harmonic approximation, there would be a severe displacement and distortion of the relative positions of the ions. This is because at such a high temperature, the amplitude of vibrations is so large that the ionic forces are almost broken and melting starts to occur. As a result, the quasi-harmonic model is no longer accurate as this model only accounts for linear motion of ions or atoms. A further consequence of the approach of the temperature to the melting point of MgO is that phonon-phonon interactions become significant because of the greater abundance of ions being in higher excited thermal phonon states. As a result of these interactions, phonons decay into lower excited state phonons. It should be noted that in the harmonic and quasi-harmonic approximation, the phonons are said to be independent and non-interacting. However, the fact that at higher temperatures, the phonon energies increase and are likely to interact means that the quasi-harmonic approximation will break down. This is because the quasi-harmonic interaction will have ignored these significant interactions. Overall, the quasi-harmonic model doesn't not predict the motion of ions at these temperatures very well. So overall, as the temperature approaches the melting point of MgO, the simulated phonon modes become less accurate in their description of the actual motion of the ions in the solid.

3. Comparing a diatomic molecule to a solid

It is important to note that the quasi-harmonic model allows the bond length to change with temperature as a result of the introduction of the anharmonic contributions. This change in bond length is not allowed in the harmonic model. Thus, for a diatomic molecule following an exact harmonic potential, the equilibrium bond length would not change with increasing temperature as a result of this symmetry to the potential energy surface of the harmonic oscillator. When compared to the quasi-harmonic model used to model solids, the bond lengths in the solid is allowed to increase with temperature as a result of the added anharmonic contributions to the harmonic oscillator resulting in this quasi-harmonic approximation in which bond lengths can increase to the point of dissociation.

This same behaviour can be modelled for diatomics if a Morse/Lennard-Jones potential, which are asymmetric potentials, had been used to model the bond lengths. The use of such potential energy surfaces means that the bond length of the diatomic would increase with temperature in which the average value of the interatomic distance is no longer constant as is the case with the harmonic oscillator.

The Thermal Expansion of MgO using the Molecular Dynamics Simulation

Now, the quasi-harmonic approximation will be compared with the Molecular Dynamics simulation. The MgO solid was investigated using the Molecular Dynamics simulation which requires the use of a different cell to that used in the quasi-harmonic approximation. In the molecular dynamics simulation, a 2x2x2 supercell of conventional unit cells were used to model the MgO (c.f. a primitive unit cell was used in the quasi-harmonic approximation). So, to calculate the thermal expansion of the MgO using the Molecular dynamics simulation, the supercell containing 32 MgO units should be used. The cell volume per formula unit of MgO was calculated as temperature was varied and the results for both the quasi-harmonic approximation and the Molecular Dynamics simulation are given below (Graph 4).

As suggesting earlier, when discussing the phonon DOS, a more accurate result can be obtained using larger grid sizes. The same principle can be applied here; using larger supercells will generate more accurate results but will be more computationally demanding and the computation will take longer to complete.

Graph 4 shows the comparison of the change in the cell volume with temperature using both the quasi-harmonic approximation and the Molecular Dynamics simulation. Both methods give an increase in cell volume with temperature which is as expected due to the thermal expansion of MgO. Again, one can calculate the volumetric thermal expansion coefficient for MgO using the molecular dynamics approach, in the temperature range 100-1000 K.

K-1

where the "V" in the "1/V" term is the initial volume of MgO at 0 Kelvin.

Comparing this with the volumetric thermal expansion coefficient using the quasi-harmonic approximation, αV (QHA) = 2.249 x 10-5 K-1, which shows that both methods give very similar value for the volumetric thermal expansion coefficient. It should be noted that the volumetric thermal expansion coefficient from the molecular dynamics simulation and the volumetric thermal expansion coefficient from the quasi-harmonic approximation were calculated in the temperature ranges 100-1000 K and 0-1000 K respectively.

From Graph 4, there are a few important notes that one should observe. Firstly, the cell volume predicted using the Quasi-Harmonic approximation is always larger than that predicted using the Molecular Dynamics simulation. However, this difference in predicted cell volumes is much larger at lower temperatures, i.e. in the range 0-400 K, where the cell volume predicted using the molecular dynamics simulation deviates away from the expected values which shows the failure of the Molecular Dynamics simulation at lower temperatures. At temperatures between 400 - 1000 K, the cell volumes predicted by both methods match very closely and the results are consistent (even though the cell volume predicted by the Quasi-Harmonic method is still larger).

It should be further noted that the MD simulations produced results that followed a linear trend as expected. However, the quasi-harmonic approximation produced results that followed a polynomial fit. This difference can be simply be explained by that fact that the quasi-harmonic approximation is a simple extension from the harmonic model which has a quadratic relationship between the potential energy and the displacement of atoms from the equilibrium position. But, this difference is much smaller at higher temperatures at which both approaches produces similar results. Overall, the data from the molecular dynamics simulation can be made more accurate by using larger cell sizes to sample rather than the 32 unit supercell that had been used. Using a larger sample size in the molecular dynamics simulation will allow any inaccuracies to be removed.

Lastly, one can state the molecular dynamics simulation allows the ions in the MgO solid to move in 3 dimensions whereas the the quasi-harmonic approach only allows the motion of ions in 1 dimension. As a result, the thermal expansion predicted by the molecular dynamics simulation produces a very irregular and distorted structure with increasing temperatures. This means that the molecular dynamics simulation will provide cell sizes (volume) that are larger than that predicted by the quasi-harmonic model at higher temperatures than 1000 K. In other words, the thermal expansion predicted by the molecular dynamics simulation leads to a distorted structure to the MgO lattice in which the geometry and shape has been changed significantly.

Conclusions

The major aim of this experiment was to study the thermal expansion of MgO. This was undertaken by the use of two different methods, the Quasi-Harmonic (QH) approximation and the molecular dynamics (MD) simulation. From the results obtained, it can be seen that the both of these approaches correctly predict the thermal expansion of MgO even though the results obtained had limited accuracies due to the assumptions involved.

The thermal expansion of MgO had been correctly predicted at low temperatures using the QH approximation with high accuracy but at higher temperatures, the accuracy fell away. This inaccuracy at higher temperatures is due to the fact that the QH approximation method is far too simplistic and too many approximations (e.g. the Born-Oppenheimer approximation and the introduction of the anharmonic factor to harmonic model being the major approximations) have been used in order to provide faster computation of results. Thus, this results in the breakdown of the model at higher temperatures and thus the thermal expansion of MgO isn't predicted correctly at higher temperatures using the QH approximation. Moreover, QH approximation works well at lower temperatures due to the lack of extensive anharmonicity which can potentially distort the interionic bond distances. However, a way to improve the accuracy of these results is to implement another method that involves the anharmonic contribution that uses fewer approximations. So it would be desirable to use a model with fewer approximation whilst still contain the anharmonic model for a system. The problem with using a model with fewer approximations would be the fact that the computational times would be longer; however, the acquisition of more accurate results would be highly beneficial in this case.

When using the MD simulation, no approximations were required but this was traded off against the fact that a larger cell size was required in order to do that computations. In this case a 32 MgO unit cell was required (c.f. a primitive cell for the QH approximation) to enable calculations to be completed at higher temperatures. A larger cell size was required due to the nature of the model which calculates averages of properties of the atoms involves. In terms of the results, the molecular dynamics model faces limitations at lower temperatures, due to the small time scale as well as the lack of thermal energies to match the kinetics of the process. A possible improvement could be the use of larger supercells, even though the computations will be more expensive in terms of time. Using super cells larger than the 32 MgO unit cell used would allow more accurate results to be obtained as there would be a greater number of sampled points in the computations.

Despite the drawbacks of the two methods, both did allow the study of the thermal expansion and correctly predict the thermal expansion of MgO under the conditions of the computations whilst allowing the calculations to be completed in a small timescale. Studies included looking at how the free energy of MgO varied with increasing temperature as well how the cell volume changed with temperature. One further point to note is that any model that would be used to model the thermal expansion of solid MgO would fail at temperatures close to the melting point of MgO as MgO is in the liquid state at this temperature. Thus, accordingly, the QH approximation failed at temperatures close to the melting point.

Further work could have been implemented into this study. For example, more thermodynamic properties of MgO, such as the piezoelectric properties, could have been calculated and compared using the QH approximation and the MD simulation.

Calculations

Calculation of the Linear Thermal Expansion Coefficient for MgO using the Quasi-Harmonic Approximation from 0-1000 K

The Linear Thermal Expansion Coefficient is calculated as follows.

K-1

where the "L" in the "1/L" term is the empirical lattice constant of MgO at 0 Kelvin i.e. it's initial length prior to thermal expansion.

Calculation of the Volumetric Thermal Expansion Coefficient for MgO using the Quasi-Harmonic Approximation from 0-1000 K

The volumetric Thermal Expansion Coefficient is calculate as follows.

K-1

where the "V" in the "1/V" term is the initial volume of MgO at 0 Kelvin.

References

<references> [1]. [2]. [3]. [4]. [5]. [6]. [7]. [8]. [9]. [10].

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 C. S. Sunandana, Introduction to Solid State Ionics: Phenomenology and Applications, CRC Press, Boca Raton (Florida), 2015 .

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Y. Kumagai, F. Oba, Phys. Rev. B, 2014, B 89, 195205, DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevB.89.195205.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 X. Wu, L. Liu, W. Li, R. Wang, Q. Liu, Computational Condensed Matter, 2014, 1, pp 38-44, DOI:10.1016/j.cocom.2014.10.005.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 R. Hoffmann, Angewandte Chemie, 1987, 26 (9), pp 846-878, DOI: 10.1002/anie.198708461.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 J. Callaway, X. Zou, D. Bagayoko, Phys. Rev. B., 1983, 27 (2), pp 631-635, DOI:10.1103/PhysRevB.27.631 .

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 J. A. Kaduk, J. Faber, The Rigaku Journal, 1995, 12 (2), pp 14-34.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 J. A. Rodriguez, M. Fernandez-Garcia, Synthesis, Properties, and Applications of Oxide Nanomaterials, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken (New Jersey), 2007.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 B. S. Mitchell, An Introduction to Materials Engineering and Science for Chemical and Materials Engineers, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken (New Jersey), 2004.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 U. Rössler and R. Blachnik, Magnesium Oxide Crystal Structure, Lattice Parameters, Thermal Expansion, In: II-VI and I-VII compounds; semimagnetic compounds, Springer, Berlin, 1999, 1-6.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 O. L. Anderson, K. Zu, J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data., 1990, 16, p 69.