Rep:Mod:TheWongAndWindingRoad

Computational Chemistry Laboratory: Module 1

by Eugene Wong

Computational molecular modelling is an important aspect of chemical research, as it allows for precise predictions and measurements regarding the physical properties of molecules to be made. This wiki entry aims to demonstrate the merits and limitations of molecular modelling, particularly in the field of physical organic chemistry. Two computational methods for the optimisation of molecular geometries will be employed here: Allinger's MM2 method, a classical Hookean model which involves mainly steric repulsions; and the MOPAC method which involves semi-empirical molecular orbital (MO) calculations. The need for methods which consider the involvement of MOs, such as MOPAC, will also be emphasised, due to the limitations of classical models (MM2) in ascertaining the role of orbital interactions in in reactivity and selectivity.

The prediction of spectral data via computational methods is also possible, and the Gaussian program will be used to generate these spectra, in order to ensure effective characterisation of these optimised geometries. This wiki will culminate in an investigation of the regioselectivity of a Baeyer-Villiger reaction, during which the aforementioned computational methods will be put to use.

Diels-Alder Dimerisation of Cyclopentadiene

Cyclopentadiene C5H6 is used most widely in its deprotonated C5H5- form, as a reagent in the synthesis of metallocene sandwich complexes. However, in its diene form, it is prone to dimerisation via a Diels-Alder mechanism, and very often it has to be subjected to thermal cracking prior to synthesis, to convert the dimer into the monomer. This section will largely involve the use of Molecular Mechanics simulations, specifically for the study of the dimerisation process.

The Stereoisomers of Dicyclopentadiene

The [4+2] dimerisation of cyclopentadiene leads to the formation of two stereoisomeric dimers, namely an exo- form 1, and an endo- form 2, depending on the orientation of the cyclopentadiene units (see Figure 1 for mechanism). MM2 force field calculations (Table 1) show 1 having a lower total energy than 2, with the major contributor to this energy difference being torsional strain (ca. 1.85 kcal mol-1 higher for the endo-dimer), alongside minor contributions from bending and van der Waals interactions. The Jmol simulations in Table 1 also include dihedral angle measurements for both dimers, and show that while 1 has the least torsional strain (torsion angle = 178.6o, close to preferred antiperiplanar conformation angle of 180o), 2 has significant torsional strain (torsion angle = 45.8o, synclinal conformation). These force calculations show that 1 is thermodynamically more stable than 2. However given that 2 is formed preferentially over 1, it follows that thermodynamic arguments are insufficient in predicting the stereochemistry of the product, and kinetic factors (such as transition state stabilisation) must be considered.

| Interaction Energy (kcal mol-1) | (1), exo-dimer | (2), endo-dimer | Difference (Energy(1)-Energy(2)) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stretch | 1.25 | 1.25 | 0.00 |

| Bend | 20.58 | 20.85 | -0.27 |

| Stretch-Bend | -0.84 | -0.84 | 0.00 |

| Torsion | 7.66 | 9.51 | -1.85 |

| Non-1,4 VDW | -1.42 | -1.54 | 0.12 |

| 1,4 VDW | 4.23 | 4.32 | -0.09 |

| Dipole/Dipole | 0.38 | 0.45 | -0.07 |

| Total Energy | 31.88 | 34.00 | -2.12 |

With reference to Figure 2[1], it can be seen that the transition state (TS) for the formation of the endo-dimer is approximately 1 kcal mol-1 lower in energy. This leads to a higher rate of reaction for the endo-dimer 2, resulting in it being the major product. Figure 3 shows that use of a Frontier Molecular Orbital (FMO) approach can be used to explain the extra stability of the TS for the endo-dimer, due to the secondary molecular orbital interactions present (which the exo-dimer TS lacks).

Hydrogenation of the Cyclopentadiene Endo-dimer

Dihydrogenation of 2 leads to two regioisomeric products, 3 and 4. MM2 energy minimisation gave a lower total energy for 4, and this is attributed to the lower bending strain for the cyclic alkene functionality in 4. The C=C-C angles for 3 and 4 are 108o and 112o, respectively; it can then be seen from here that 4 suffers less bending strain due to its C=C-C bending angle being closer to the preferred alkene sp2 carbon geometry of 120o. 4 is hence the more thermodynamically stable isomer, compared to 3. However, the limitations of this molecular mechanics simulation are once again manifested; in the lack of information regarding the kinetics of this hydrogenation reaction. It can be concluded that hydrogenation under thermodynamic control will lead to product 4, prior to the formation of the tetra-hydrogenated product.

| Interaction Energy (kcal mol-1) | (3) | (4) | Difference (Energy(3)-Energy(4)) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stretch | 1.28 | 1.10 | 0.18 |

| Bend | 19.86 | 14.52 | 5.34 |

| Stretch-Bend | -0.83 | -0.55 | -0.28 |

| Torsion | 10.81 | 12.50 | -1.69 |

| Non-1,4 VDW | -1.22 | -1.07 | -0.15 |

| 1,4 VDW | 5.63 | 4.51 | 1.12 |

| Dipole/Dipole | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.02 |

| Total Energy | 35.69 | 31.15 | 4.54 |

Summary of Molecular Mechanics Simulations

These two simulations show that at best, only thermodynamic predictions can be made from the use of Molecular Mechanics simulations such as MM2 and MMFF94. Despite being useful at optimising molecular conformational geometries, these methods do not yield any insight into the impact of orbital effects, which are important factors in most stereochemical outcomes (as seen earlier in the dimerisation of cyclopentadiene).

Stereochemistry and Reactivity of an Intermediate in the Synthesis of Taxol

This section will discuss the relative thermodynamic stabilities of a pair of atropisomers formed in the synthesis of Taxol. Atropisomerism arises from restricted rotation about a σ-bond, due to steric constraints. This presents a higher energy barrier to rotation, which ultimately results in the isolation of the two distinct conformations at ambient conditions. The atropisomeric pair, 9 and 10, differ only in the orientation of the carbonyl group with respect to the bridgehead carbon (syn- and anti-, see Figure 5 below).

As with the previous isomer pairs, MM2 calculations were used to determine the minimised energy of the molecules. The results are summarised in Table 3. An additional simulation method, MMFF94 (Merck Molecular Force Field) was used as well, to provide a more in-depth analysis - MMFF94 calculations take intramolecular interactions (i.e. dispersions) into consideration, in addition to the classical two-body spring model employed in MM2.

Relative Thermodynamic Stability of Atropisomers 9 and 10

MM2 and MMFF94 force-field calculations were used to determine the stability of each atropisomer, on the basis of the amount of strain present. The results are as follows:

| Interaction Energy (kcal mol-1) | (9), syn-carbonyl | (10), anti-carbonyl | Difference (Energy(9)-Energy(10)) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stretch | 2.78 | 2.61 | 0.17 |

| Bend | 16.54 | 11.33 | 5.21 |

| Stretch-Bend | 0.43 | 0.34 | 0.09 |

| Torsion | 18.26 | 19.67 | -1.41 |

| Non-1,4 VDW | -1.55 | -2.15 | -0.60 |

| 1,4 VDW | 13.11 | 12.87 | 0.24 |

| Dipole/Dipole | -1.72 | -2.00 | 0.28 |

| Total Energy | 47.84 | 42.68 | 5.16 |

| MMFF94 Minimisation | 70.55 | 60.56 | 9.99 |

From Table 3 it can be seen that despite the differences in the MM2 and MMFF94 computational methods employed, 10 is still established as the more thermodynamically stable atropisomer of the two. MM2 calculations show that bending strain is the major cause of the energy difference. Closer inspection of the geometries (see annotated Jmol files in Table 3) of the carbonyl sp2 carbon atom as well as the adjacent sp3 carbon atom (nearer the bridgehead) gives the following geometries: 9 (sp2 C angle = 123.4o; sp3 C angle = 123.1o) and 10 (sp2 C angle = 118.3o; sp3 C angle = 118.2o). It is clear that 10 suffers less bending strain as its sp2 carbon angle is closer to the preferred angle of 120o, in addition to the fact that its sp3 carbon angle is less distorted from the preferred angle of 109o, all of these with respect to the more strained bond angles in 9. The anti-carbonyl 10 is thus the more stable of the pair and is formed on leaving to stand (thermodynamic equilibrating conditions).

Hyperstable Olefins: The Stability of Atropisomer 10 as Compared to its Hydrogenated Derivative 11

With 10 established as the more stable atropisomer, the MM2 and MMFF94 minimisation energies of its hydrogenated derivative 11 were calculated for comparison (minimisations involved the chair conformers of the fused 6-membered ring):

| Interaction Energy (kcal mol-1) | (10), anti-carbonyl | (11), hydrogenated anti-carbonyl | Difference (Energy(10)-Energy(11)) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stretch | 2.61 | 2.84 | -0.23 |

| Bend | 11.33 | 14.22 | -2.89 |

| Stretch-Bend | 0.34 | 0.67 | -0.33 |

| Torsion | 19.67 | 22.13 | -2.46 |

| Non-1,4 VDW | -2.15 | -2.67 | 0.52 |

| 1,4 VDW | 12.87 | 15.90 | -3.03 |

| Dipole/Dipole | -2.00 | -1.73 | -0.27 |

| Total Energy | 42.68 | 51.36 | -8.68 |

| MMFF94 Minimisation | 60.56 | 71.45 | -10.89 |

The results from Table 4 indicate that 11 (MM2 energy = 51.36 kcal mol-1) is more thermodynamically unstable with respect to 10 (MM2 energy = 42.68 kcal mol-1), which means that the alkene moiety in 10 is stable to hydrogenation. A similar trend is also displayed in the MMFF94 minimisation energies. Closer analysis of the MM2 energies shows that the bending, torsion and 1,4 van der Waals' interaction energies are responsible for the destabilisation of 11.

Additional Bending Strain in 11

With respect to the C1 carbon atom (labelled green in the Jmol files), it is seen that rehybridisation from sp2 in 10 to sp3 in 11 results in little change in geometry (bond angle changes from 122.7o in 10 to 118.9o in 11). In 10, the bonding angle is close to the preferred sp2 geometry (120o), but in 11, the angle deviates by a large amount from the preferred sp3 geometry (109o). This is one source of strain and destabilisation in 11.

Additional Torsional Strain in 11

11 also possesses a significant amount of torsional strain as a result of hydrogenation of the double bond. The almost-eclipsed conformational orientation of the added H19 and H27 atoms (labelled blue in the Jmol file) have a dihedral angle of 14o, and this provides evidence of torsional strain (the other atoms bonded to the involved carbon centres are also subject to this), which is otherwise absent in the alkene 10.

Additional 1,4 van der Waals' Strain in 11

Yet another consequence of hydrogenation of the double bond in 10 is the repulsive 1,4 van der Waals' interactions between the H19 and H27 atoms mentioned earlier. The distance between these H atoms is 0.208 nm (or 2.08 Å), which is indicative of a repulsive interaction [2].

Summary of Strain Effects

The lower strain present in the unsaturated compound 10 with respect to its hydrogenated derivative 11 is a characteristic of hyperstable olefins[3]. This phenomenon occurs in alkenes which have their C=C bonds conformationally "locked" in their bending and torsional geometries. Reactions involving this bond involve changing the hybridisation with retention of these geometries (~120o bending angle as seen above), which introduces a high amount of bending strain for any other hybridisation apart from sp2. Also seen above is the syn-addition of a substrate across the double bond leading to torsional and 1,4-repulsive strain, which is also due to this "locked" geometry. This explains the apparent stability of the C=C bond with respect to hydrogenation, as well as any other addition reaction.

Overall Thermodynamic Predictions involving 9, 10 and 11

It was shown in this section that molecular mechanics methods such as MM2 and MMFF94 are able to determine relative thermodynamic stabilities of two atropisomers (comparison between 9 and 10), and also provide an quantitative description of the lack of reactivity of hyperstable olefins towards addition reactions (comparison between 10 and 11).

Regioselective Electrophilic Addition to an Asymmetric Non-Conjugated Decalin Di-alkene

In this section, MOPAC molecular modelling is used to explore and explain the observed reactivity of the asymmetric decalin di-alkene 12 (see Figure 7) in its carbenylation[4] to give 12a, as well as the effect of hydrogenation of the double bond anti- to the Cl atom on the C-Cl stretching frequency (via comparison of 12 and 13). The MOPAC method employed was MOPAC/RM1 instead of MOPAC/PM6, due to a bug in the PM6 programming, which led to asymmetric molecular orbitals obtained (Figure 8). The symmetry of the molecule will also be briefly discussed, which provides a basis for why the asymmetric orbitals obtained via the PM6 treatment are not a feasible result.

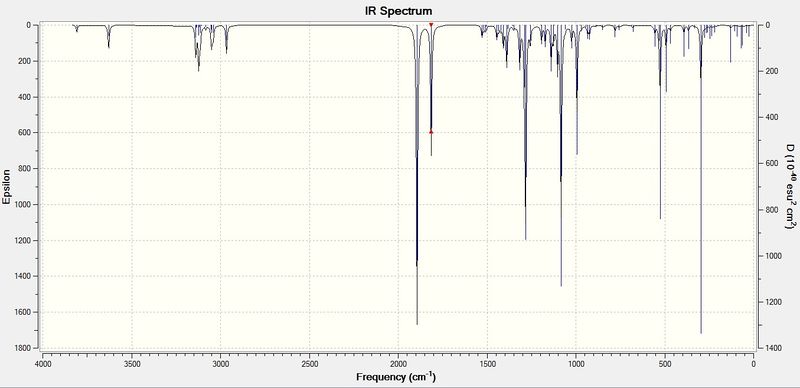

The infrared (IR) vibrational properties of 12 and 13 will be simulated using a Gaussian optimisation, and used to predict an IR spectrum for each of these compounds. This will be used largely in conjunction with the MOPAC method to characterise the C-Cl and C=C functionalities within each molecule, and confirm the assertions made in the latter part of this section.

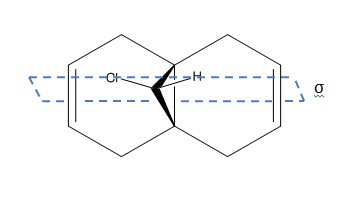

As seen in Figure 9, the only symmetry element present in 12 (apart from E) is the mirror plane that bisects both C=C bonds and is in the same plane as the bridgehead C-Cl and C-H bonds. The symmetry of the molecular orbitals must adhere to this mirror plane, and this is a reason for the MOPAC/PM6 technique not being used, due to the asymmetric orbitals obtained.

The results of MOPAC/RM1 treatment are displayed in Table 5 below:

| Molecular Orbital | Picture | Molecular Orbital | Picture |

|---|---|---|---|

| HOMO-1 |  |

HOMO |  |

| LUMO |  |

LUMO+1 |  |

| LUMO+2 |  |

- | - |

Nucleophilicities of the Double Bonds

As seen in Table 5, the HOMO orbital involves the π-electron cloud of the C=C bond which is endo- with respect to the C-Cl bond, and the HOMO-1 involves the C=C bond exo- to the C-Cl bond. This provides an explanation for the regioselective carbenylation of the endo- C=C bond as seen earlier in Figure 7, as the endo- C=C bond is higher in energy and is thus more reactive, especially towards electrophiles like dichlorocarbene. It should also be noted that due to steric hindrance from the Cl atom, the electrophile adds to the opposite face of the endo- double bond.

Effect of Hydrogenating the Exo- Double Bond on C-Cl Stretching Frequencies

Special attention must be paid to the LUMO obtained in Table 5, which can be thought of as a σ* anti-bonding orbital involving C and Cl. The back lobe of this orbital is pointed at the exo- double bond, and the π-cloud of the double bond is in the correct orientation for donation into the σ* orbital. The effects of this are weakening of the exo- double bond and the C-Cl bond, due to donation of electron density from the π bonding orbital and population of the C-Cl antibonding orbital, respectively. This is confirmed by the IR spectra of the di-alkene 12 and 13 (where the exo double bond has been hydrogenated).

| IR Stretch | 12(cm-1) | 13(cm-1) |

|---|---|---|

| C-Cl | 770.86 | 774.88 |

| C=C (endo-) | 1757.34 | 1758.10 |

| C=C (exo-) | 1737.03 | - |

These spectral data show that donation of the exo- double bond π-electrons into the C-Cl σ* orbital does indeed lead to slight weakening of the C-Cl bond, as the C-Cl IR stretch in 12 (770.86 cm-1) is about 4 cm-1 lower than it is in 13 (774.88 cm-1). Another factor reinforcing this is the fact that the exo- double bond (1737.03 cm-1) is weaker than the endo- double bond (1757.34 cm-1) by about 20 cm-1, which is attributed to the aforementioned donation of exo- double bond electron density. Hydrogenation of this exo- double bond causes the stretch at 1737.03 cm-1 to disappear, which further confirms this IR assignment.

Summary of MO Modelling

The orbitals obtained via this MOPAC method allowed for the determination of alkene regioselectivity in 12, on the basis of relative energies of both C=C bonding orbitals. This method also allowed for a brief investigation of the stereoelectronic effect concerning the exo- double bond and the C-Cl antibonding orbital in 13, which leads to C-Cl bond weakening.

Diastereospecificity in Monosaccharide Glycosidation Reactions

Glycosidation reactions involve formation of an oxonium cation via loss of the anomeric hydroxyl, and attack of a nucleophile on the oxonium cation. Figure 12 describes a typical glycosidation, with the nucleophile being an alcohol. The limitation of this glycosidation is that the α-glycoside is formed as a major product due to the anomeric effect, which involves anti-parallel overlap of one of the cyclic ether oxygen lone pairs with the axial C-Nu (-OR in Figure 12) σ* orbital, which stabilises the α-glycoside.

To avoid this issue of equilibration to give the α-glycoside (or α-anomer), neighbouring group effects (see Figure 13) are employed in carboyhydrate synthesis, as a means of allowing for diastereoselective glycosidation (α- or β-anomer). MM2 and MOPAC/PM6 methods will be used in this section, as a means of investigating the said neighbouring group effect.

Figure 13 depicts an equatorial -OAc group in A protecting the axial position on the anomeric carbon, and leading to the formation of the β-anomer (via oxonium cation C, and attack of Nu on the top face). Conversely, the axial -OAc group in B protects the adjacent equatorial position on the anomeric carbon, leading to the α-anomer (via D) as the Nu can only attack from the bottom face. It is taken for granted that these neighbouring group effects only serve in protecting the anomeric carbon on the same face of the ring, but conformations where the acyl oxygen is oriented differently, as if to protect the opposite face (A' to C' ; B' to D' ), will also be explored.

The -OH groups in the 6 membered glucose ring were replaced with -OMe groups, to avoid possible H-bonding interactions which would interfere with the optimisation of the molecule. The -OMe groups are of the smallest possible alkoxy moiety, which simplifies the calculation process. Table 7 shows the results of MM2 energy calculations on the conformations A to D and A' to D' .

| Interaction Energy (kcal mol-1) | A | A' | B | B' | C | C' | D | D' |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stretch | 2.38 | 2.43 | 2.53 | 2.41 | 1.96 | 2.63 | 2.05 | 2.62 |

| Bend | 9.19 | 9.03 | 9.67 | 10.53 | 13.17 | 17.93 | 13.82 | 16.62 |

| Stretch-Bend | 0.83 | 0.84 | 1.01 | 0.78 | 0.69 | 0.68 | 0.64 | 0.75 |

| Torsion | 1.12 | 2.68 | 1.14 | 3.57 | 8.16 | 6.34 | 8.22 | 7.31 |

| Non-1,4 VDW | -2.69 | -2.89 | -0.91 | -1.72 | -2.98 | -4.15 | -3.22 | -2.98 |

| 1,4 VDW | 19.10 | 19.50 | 18.24 | 20.18 | 17.79 | 19.13 | 18.62 | 19.38 |

| Charge/ Dipole | -5.79 | -4.24 | -11.80 | -14.14 | -9.61 | 2.67 | -8.04 | -2.76 |

| Dipole/Dipole | 5.59 | 4.23 | 6.91 | 4.16 | -2.31 | -1.34 | -0.16 | -1.31 |

| Total MM2 Energy | 29.73 | 31.59 | 26.79 | 25.78 | 26.87 | 43.90 | 31.93 | 39.63 |

The results of MM2 calculations are not conclusive in determining the stabilisation energy of the neighbouring group effect as the MM2 method relies mostly on steric repulsions, and does not recognise the attraction between the oxonium ion and the acyl oxygen atom. With respect to the annotated Jmol files for A, A' , B and B' , these MM2-minimised conformations possess a C-O (oxonium C and acyl O) distance higher than 0.2 nm (or 2Å, which shows that there is no bonding interaction), and their O-C-O angles do not match the Burgi-Dunitz angle of 107o, for the approach of a nucleophile towards a carbonyl. It becomes clear that orbital interactions must be taken into consideration, in order to determine the extent of bond formation between the acyl oxygen and the oxonium carbon. The MOPAC/PM6 method does exactly this, and the results are summarised in the following Table 8.

| Interaction Energy (kcal mol-1) | A | A' | B | B' | C | C' | D | D' |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heat of formation | -87.82 | -68.91 | -82.27 | -62.17 | -91.65 | -66.84 | -88.73 | -66.49 |

These PM6 calculated heats of formation and optimised geometries (see annotated Jmol files) give a more conclusive result: A and B have more exothermic formation energies, as well as lower C-O (oxonium C and acyl O) distances (0.159 nm for both A and B; c.f. 0.14 nm for typical C-O bond[9]) than A' (0.298 nm) and B' (0.340 nm). A and B have the acyl oxygen approaching the oxonium C=O at approximately 105o, which resembles the Burgi-Dunitz trajectory in both cases. The same, however, cannot be said for A' and B' , as their angles of 158o and 139o are too large to be indicative of a nucleophile approaching the oxonium C=O. It is also worth noting that the formation energy for A (-87.82 kcal mol-1) is close to that of C(-91.65 kcal mol-1), where the conformational geometries are similar (the C-O bond has already been formed in C). The remaining pairs of optimised geometries also follow this trend: A' and C' ; B and D; B' and D' , as seen in the table above.

The additional exothermic formation energies of X compared to X' (where X = A, B, C or D) are significant (approximately 20 kcal mol-1 more negative in the case of X), and these optimised geometries show that formation of a bond between the acyl O and oxonium C is more favourable when on the same face of the ring, i.e. axial -OAc forms equatorial C-O bond with the oxonium carbon and promotes α-anomer formation; vice versa for equatorial -OAc, axial C-O bond and β-anomer formation. The driving force, which leads to these more exothermic energies, is the ease at which the acyl oxygen may approach the oxonium carbon on the same face, as opposed to having to "reach around" to attack on the opposing face, the latter situation leading to more strain.

Summary of Optimisation Calculations

MOPAC/PM6 was used effectively in this section to rationalise the neighbouring group effect, and the interactions between the neighbouring -OAc and anomeric (oxonium) carbon were modelled to reasonable accuracy (c.f. the compounds with the acetyl acyl oxygen ALREADY bonded to the oxonium carbon, Table 8). MM2 calculations were shown to be insufficient in this area, highlighting yet another case where factors such as orbital interactions have to be considered as well.

Mini-Project: Investigating the Regioselectivity of a Baeyer-Villiger Oxidation

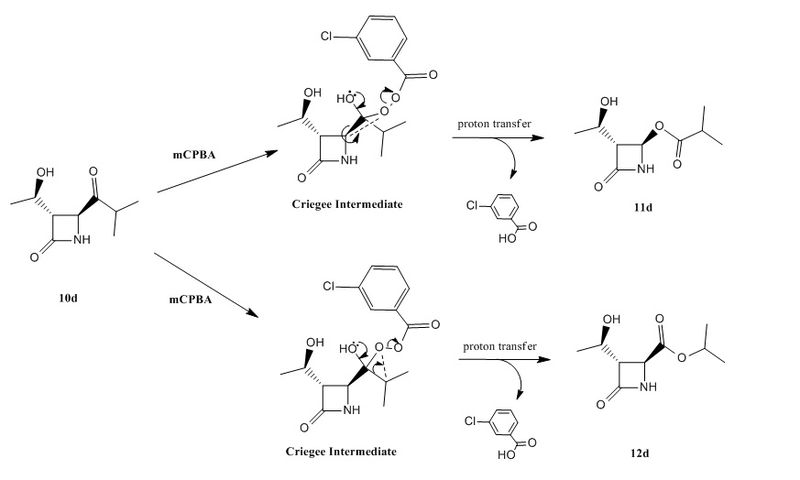

The Baeyer-Villiger (BV) reaction is a useful synthetic method for the conversion of ketones to esters. This reaction results in the insertion of an oxygen atom between the carbonyl carbon and the α-carbon. Typical BV reactions allow for regioselectivity even in reactions where the substrate is an asymmetric ketone, based on the ability of the migrating species to stabilise positive charge (in the second step of the mechanism involving the Criegee intermediate, see Figure 14).

The mechanism for this oxidation involves nucleophilic attack on the ketone carbonyl to give a tetrahedral Criegee Intermediate, which undergoes a rearrangement with migration of one of the ketone α-carbon atoms to give the ester. As seen in Figure 14, either the β-lactam (cyclic amide) functionality or the isopropyl group may migrate, and both 11d and 12d are formed in an approximately 1:1: yield. Laurent and co-workers [11] proposed that both the β-lactam and isopropyl groups were thus equally able to stabilise the positive charge that forms in the transition state as a result of the migration. This section will discuss the use of computational techniques in this area of research, especially for predicting NMR and IR spectra, in order to confirm the regiochemistry of the products obtained.

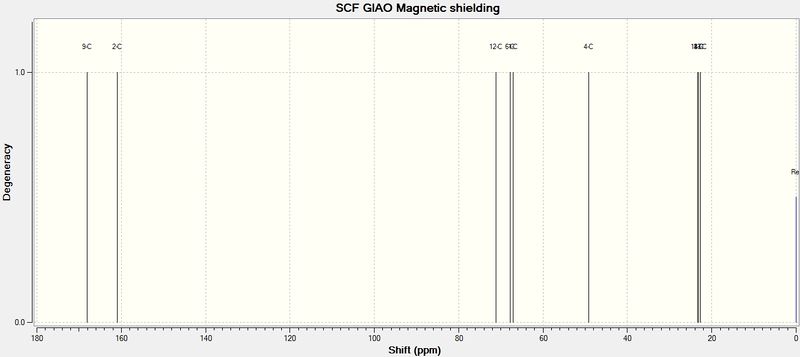

Predicted NMR Spectra

This computational experiment made extensive use of the 13C (and to a small extent 1H) NMR prediction offered by the Gaussian simulation program. Firstly, both molecules 11d and 12d were sketched and optimised via the MOPAC/RM1 method (Table 9), and then using the Gaussian program (the RM1 method being used, pre-optimisation, to save time spent during the Gaussian computations). The NMR data obtained is shown in Table 10 further on, with reference to the numbered structures in Figure 15.

| Interaction Energy (kcal mol-1) | 11d | 12d |

|---|---|---|

| Heat of formation | -181.03 | -170.61 |

| C no. | δ11d,calculated (ppm) | δ11d,literature (ppm) | Difference in δ11d values (lit. value - calc. value) (ppm) | δ12d,calculated (ppm) | δ12d,literature (ppm)) | Difference in δ12d values (lit. value - calc. value) (ppm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 163.8 | 167.2 | 3.4 | 166.7 | 168.3 | 1.6 |

| 3 | 63.0 | 63.9 | 0.9 | 67.1 | 64.0 | -3.1 |

| 4 | 78.0 | 75.9 | -2.1 | 49.2 | 50.0 | 0.8 |

| 5 | 177.9 | 177.6 | -0.3 | 173.6 | 170.8 | -2.8 |

| 6 | 38.0 | 34.0 | -4.0 | 71.2 | 69.7 | -1.5 |

| 7 | 20.0 | 18.8 | -1.2 | 22.7 | 21.3 | -1.4 |

| 8 | 20.2 | 18.9 | -1.3 | 23.4 | 21.9 | -1.5 |

| 9 | 66.2 | 65.2 | -1.0 | 67.8 | 64.5 | -3.3 |

| 10 | 23.1 | 21.3 | -1.8 | 23.1 | 21.8 | -1.3 |

The chemical shifts for the carbonyl carbons atoms were subjected to a correction δcorr = 0.96δcalc + 12.2 (already reflected in the values above), to correct for spin-orbit coupling[14]. These computed values differ from the literature by no more than 5ppm. This shows that the Gaussian prediction for 13C NMR is reliable in this case.

However, it should be mentioned that this method for calculating NMR only takes one optimised conformation into consideration. For a more accurate NMR spectrum, especially in the case of a molecule where many stable conformers exist, the NMR data should be averaged over all these conformations. With respect to 13C NMR, conformational changes have little effect on the environment of the C atoms, as shown by C7 and C8, which are meant to be equivalent when averaged, but differ by as much as 0.7ppm in the case of 12d (where each carbon atom experiences a different environment, due to the asymmetry about the top and bottom faces of the lactam ring).

The assignment of the regiochemistry of both molecules can be done with ease using 13C NMR, either via computational or experimental methods. The main difference, spectroscopically, lies in the 13C NMR shifts of C4 and C6. In 11d', C4 is bonded directly to an O atom, and is more deshielded than C4 in 12d (α-carbon of the ester) C4 has a higher chemical shift value in 11d than in 12d. The same approach applied to C6 shows that C6 has a lower chemical shift in 11d as it is the ester α-carbon (compared to being bonded to an O atom in 12d).

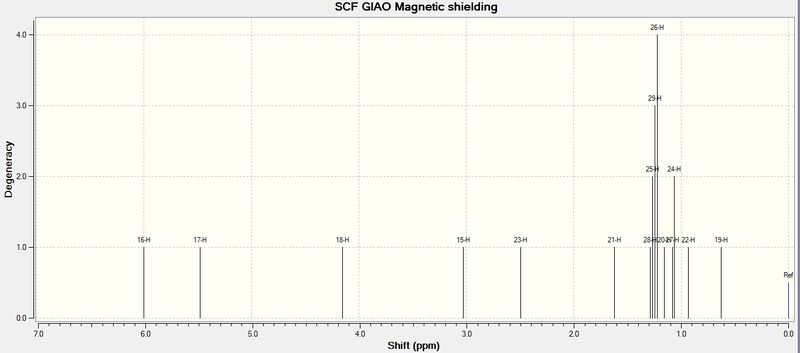

The reason for the limited use of 1H NMR calculated via the Gaussian method is attributed to the fact that optimising only one "snapshot" conformation leads to distinct chemical shift (see Figure 17) for each proton in the molecule. The shift values obtained in a conventional NMR take into account thermal fluxionality (which would result, for example, in methyl group protons being equivalent to each other). For more complex molecules, a statistical average of different optimised conformations must be used, in order to simulate an accurate 1H NMR spectrum. The calculated spectral data also does not take J-coupling into account. Thus, the simulated 1H NMR method is not as reliable as that of simulated 13C NMR.

However, use of this computational method as a means of differentiating between the two regioisomers is still possible. It is expected that the most obvious difference in 1H chemical shifts, due to deshielding effects, occurs at the C6 proton (H6), which is expected to produce a septet due to coupling with two adjacent methyl groups. The NMR data for H6 was used as calculated from Gaussian, with the septet 3J value calculated using Janocchio. The following H6 NMR data was obtained:

For 11d, δ2.49 (sept, 1H, 6.4Hz). This is slightly smaller, but still in agreement with that from the literature: δ2.60 (sept, 1H, 6.9Hz)

For 12d, δ4.91 (sept, 1H, 5.8Hz). Again, comparison shows agreement between calculated and literature values: δ5.09 (sept, 1H, 6.3Hz)

These data show that 1H NMR may be used, both in simulation and synthesis, to determine the regioisomer formed. In both cases, the difference in H6 chemical shift value between regioisomers is approximately 2.4ppm. This NMR shift can be identified by the characteristic septet splitting pattern in an experimental spectrum, while computational methods allow for pinpointing of the specific proton which possesses the H6 chemical shift, via Gaussview (and also affords calculated J-coupling values via Janocchio).

The 15 NMR spectra for 11d and 12d were also predicted by Gaussian, and their assignments are relatively straightforward: The amide N in 11d has a chemical shift of 140.5ppm, which is higher than the amide N in 12d (131.6ppm). This is due to the N atom being more deshielded, it has only two chemical bonds between it and the nearest O atom, while in 12d there are three bonds between amide N and the O atom.

However, this method of characterisation is not very feasible experimentally, due to the rarity of the 15N isotope.

Predicted IR Spectra[19],[20]

The vibrational modes were calculated using Gaussian, and displayed as follows, in Table 11.

| IR Stretch | 11d, calc.(cm-1) | 11d, lit.(cm-1) | 11dlit. - 11dcalc. | 12d, calc.(cm-1) | 12d, lit.(cm-1) | 12dlit. - 12dcalc. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N-H | 3339 | 3330 | -9 | 3319 | 3341 | 22 |

| Ester C=O | 1742 | 1783 | 41 | 1743 | 1749 | 6 |

| Amide C=O | 1669 | 1740 | 71 | 1680 | 1721 | 41 |

An empirical correction factor of 8%[21] was applied to the stretching vibrations, this is already reflected in the table above.

IR spectroscopy is not expected to be an essential tool in the assignment of the two regioisomers. This is due to the fact that both regioisomers possess the same functionalities, namely the β-lactam and the ester functionality. Without any significant conjugation effects within this moleule (which would otherwise cause a tell-tale weakening of the C=O bond), this method does not deliver the same insight that the previous methods described already have. Additionally, the large discrepancy between calculated and literature C=O stretch values (up to 71 cm-1) are an indicator of the limitations of the Gaussian computational method at describing the effects of conjugation on the C=O double bond.

The Lack of Regioselectivity: Suggested Reasons and Further Calculations

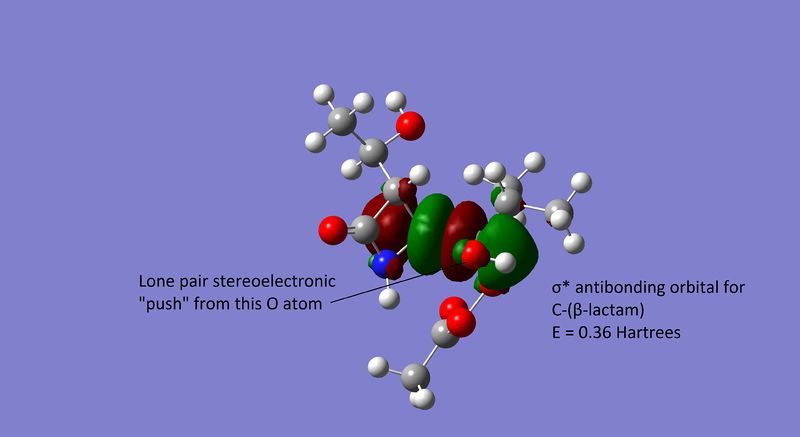

Relative Energies of the Anti-Bonding Orbitals

An important aspect of this reaction is the approximately equimolar ratio of regioisomers obtained. An initial suggestion for this was: (i) That the σ* orbitals mentioned earlier are close in energy; (ii) and that the oxygen lone pair may be stereoelectronically pushed (anti-periplanar alignment) into either the C-isopropyl σ* or C-(β-lactam)σ* with equal probability, causing the migration of either group and resulting in the formation of an equimolar regioisomeric mixture.

However, the anti-bonding orbitals computed via Gaussian[22] (using a simplified model where the m-chloro-phenyl ring was substituted for a methyl group to save time) differ by about -0.02 Hartrees (12.55kcal mol-1 or 52.51kJ mol-1), as seen below in Figures 19 and 20:

This difference in energy between both anti-bonding orbitals is too large for them to be considered close in energy. As such, it can be concluded that the lack of regioselectivity is not due to the population of both σ* anti-bonding MOs with equal probability.

Transition State Modelling

Another approach is transition state modelling. Laurent and his co-workers suggested that the β-lactam secondary carbon atom is just as adept at stabilising positive charge as the isopropyl carbon atom, and thus both may migrate with equal probability. This may be investigated by modelling the two separate transition states leading to each regioisomer (not done due to lack of time). If both transition states can be optimised to the same energy level, this would provide a good reason for the lack of regioselectivity in this reaction, as it would be concluded that both regioisomers are formed at the same rate.

Conclusions

The Molecular Mechanics methods (MM2, MMFF94, MOPAC) as well as the Gaussian DFT methods employed in this computational experiment proved to be useful in obtaining optimised molecular geometries on the basis of steric and electronic requirements. Prediction of spectral data via Gaussian DFT methods also proved to be a useful characterisation tool, especially in the case of 13C NMR. Despite the fact that this spectral prediction may be complicated by the existence of many possible conformations, it still proved useful in the assignment of the regiochemistry of the Baeyer-Villiger reaction carried out by Laurent et. al., and further calculations (such as the transition state modelling method suggested in the earlier section) would definitely provide more insight into the lack of regioselectivity encountered.

References

- ↑ M. A. Fox, R. Cardona, N. J. Kiwiet, J. Org. Chem. 1987, 52, 1469-1474 DOI:10.1021/ja00274a016

- ↑ H. Rzepa, Conformational Analysis (2nd year lecture course), http://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/local/organic/conf/

- ↑ A. B. McEwen, P. v. R. Schleyer, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1986, 108, 3951–3960DOI:10.1021/ja00274a016

- ↑ B. Halton, S. G. G. Russell, J. Org. Chem., 1991, 56, 5553–5556 DOI:10.1021/jo00019a015

- ↑

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12762 - ↑

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12763 - ↑

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12762 - ↑

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12763 - ↑ CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 92nd edition, 2011 - 2012

- ↑ M. Laurent, M. Ceresiat, J. Marchand-Brynaert, J. Org. Chem. 2004, 69, 3194-3197 DOI:10.1021/jo030377y

- ↑ M. Laurent, M. Ceresiat, J. Marchand-Brynaert, J. Org. Chem. 2004, 69, 3194-3197 DOI:10.1021/jo030377y

- ↑

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12797 - ↑

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12798 - ↑ https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=Mod:organic#Predicting_the_13C_NMR_Spectrum_of_a_compound

- ↑

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12797 - ↑

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12798 - ↑

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12797 - ↑

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12798 - ↑

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12799 - ↑

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12800 - ↑ https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=Mod:organic#Predicting_the_IR_Spectrum_of_a_compound

- ↑

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-12815