Rep:Mod:TP1414

Introduction

Gaussian and Transition State Characterization

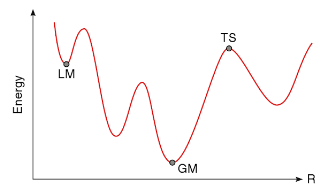

Gaussian is a molecular modelling software that allows researchers to carry out extensive investigation of molecules and their reactions. In these exercises, the transition states of several Diels-Alder reactions are located and characterized using Gaussian. A transition state is a first order saddle point on a potential energy surface (PES). It is the maximum along the minimum energy path (or reaction path) between two minima (the reactants and the products). Geometry optimization to find the minimum energy structure will usually lead to a stationary point that is closest to the initial geometry. The stationary point, where the first derivative of energy is zero, can be a global minimum, a local minimum or a saddle point. In a reaction path, the minima (global or local) correspond to the reactants and the products, while the saddle point corresponds to the transition state. To differentiate between a minimum and a saddle point, the second derivatives of energy will have to be analysed. For global or local minima, where energy rises in all directions, the second derivative of energy is positive. In contrast, for transition state, where the energy decreases in one direction (reaction path), the second derivative of energy along the reaction coordinate is negative. The analysis of the second derivatives of energy can be done by a frequency calculation of the optimized structure. If the structure corresponds to the reactants or products, all the vibrational frequencies (v) are real. In contrast, if the structure corresponds to a transition state, there will be one imaginary frequency. This imaginary frequency indicates that the force constant (k), which is given by the second derivative, is negative. [2]

Following a successful frequency calculation (one imaginary frequency) of the transition state, an Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC) calculation may be set up to examine the transition state along the minimum energy path more closely. The reaction path, or minimum energy path, can be defined as the steepest descent path from the transition state to the reactions and products.

In this exercise, two calculation methods are used. The first is the semi-empirical method PM6, a fitted method used to obtain the initial geometry of the molecule or transition state so as to save time during calculations. The second is the Density Functional Theory (DFT) method B3LYP, a method that is capable of reproducing chemical data and is used to further optimise the geometry obtained from the PM6 method.

Diels-Alder Reactions

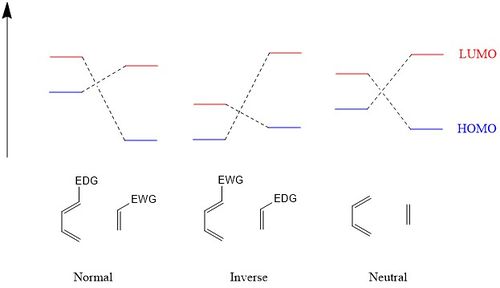

A Diels-Alder reaction is a [4+2] cycloadditon between a conjugated s-cis diene (4π-electron system) and a dienophile (2π-electron system). The reaction has a cyclic transition state with 6π-electrons, is concerted, and results in the formation of two new sigma bonds. According to the Woodward-Hoffmann Rules, the Diels-Alder reaction is thermally allowed and is an orbital-controlled reaction, in which the six electrons are interacting suprafacially. The reaction can mainly proceed in two ways:

- Normal electron demand: HOMO of diene overlaps with LUMO of dienophile

- Inverse electron demand: LUMO of diene overlaps with HOMO of dienophile

Several papers divide the Diels-Alder reactions into three categories instead of two [3] [4], the third being a neutral electron demand Diels-Alder, in which the energy separation between the HOMO and LUMO of both reactants is similar. [3] Neutral electron demand Diels-Alder reactions are seldom observed and believed to be a transition between normal electron demand and inverse electron demand Diels Alder reactions.[4] Below is a comparison of the energy levels of the HOMO and LUMO of the reactants in each case of Diels-Alder reaction where EDG = electron donating group and EWG = electron withdrawing group.

Nf710 (talk) 10:36, 7 April 2017 (BST) This is a good intro. YOu couyld have said how the PES is N dimensional. Where N is the number of degrees of freedom.

Exercise 1: Reaction of Butadiene with Ethylene

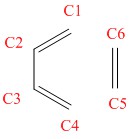

The reaction between butadiene and ethylene presents the simplest type of Diels-Alder reaction, in which butadiene is the diene and ethylene is the dienophile. This reaction yields cyclohexene as the product, and the reaction scheme is as follow:

Molecular Orbital Diagram

Only orbitals of the same symmetry can interact to form molecular orbitals. This means that only symmetric-symmetric interactions and antisymmetric-antisymmetric interactions are allowed. Symmetric-antisymmetric interactions, on the other hand, are forbidden. This is because the orbital overlap integral is non-zero for interactions between orbitals of the same symmetry and zero for interactions between orbitals of different symmetry.

As shown on the MO diagram above, both interactions (between the HOMO of butadiene and the LUMO of ethylene, and between the LUMO of butadiene and the HOMO of ethylene) occur, generating four molecular orbitals for the transition state. As the energy separation for the two interactions is similar, the reaction between butadiene and ethylene progress with aspects of both normal electron demand and inverse electron demand. This is because both butadiene and ethylene are neutral molecules without any obvious nucleophilic or electrophilic reacting centrers. Both molecules are neither electron-rich nor electron-poor. As a result, orbital overlap is possible for both HOMO-LUMO sets. Several papers classify this reaction as a neutral electron demand Diels-Alder. [3] [4] This particular Diels-Alder reaction between butadiene and ethylene is well-known for its poor yield.

Internuclear Distances

File:Internuclear distance.pdf

| C1-C2 | C2-C3 | C3-C4 | C4-C5 | C5-C6 | C6-C1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reactants | 1.34 | 1.47 | 1.34 | - | 1.33 | - |

| Transition State | 1.38 | 1.41 | 1.38 | 2.11 | 1.38 | 2.11 |

| Product | 1.50 | 1.34 | 1.50 | 1.54 | 1.54 | 1.54 |

As the reaction progresses, C1-C2, C3-C4 and C5-C6 elongate as the double bond breaks to form single carbon-carbon bonds, while C2-C3 shortens to form carbon-carbon double bond. Simultaneously, C4-C5 and C6-C1 decrease in distance and ultimately single carbon-carbon bonds are formed. A more detailed overview of how the internuclear distances change over the course of the reaction is shown on the graph on the right.

A typical carbon-carbon single bond length is 1.54 Å and a typical carbon-carbon double bond length is 1.34 Å. [5]

The Van der Waals radius of one carbon atom is 1.70 Å. [6] The length of the partly formed carbon-carbon bonds in the transition state is about 2.11 Å. This distance is shorter than twice the Van der Waals radius of carbon atom (3.40 Å), indicating bonding interactions are occuring.

Vibration and Reaction Path

The vibration that corresponds to the reaction path at the transition state is illustrated above. This vibration has an imaginary frequency that occurs at 948.97i cm-1.

The formation of the two bonds are synchronous as shown below. This means that the two sigma bonds are formed simultaneously. hence, the reaction between butadiene and ethylene goes by a concerted synchronous mechanism.

Calculation Files

File:TP1414 Exercise 1 Ethylene.log

File:TP1414 Exercise 1 Butadiene.log

File:TP1414 Exercise 1 Product.log

File:TP1414 Exercise 1 Transition State.log

File:TP1414 Exercise 1 IRC.log

Exercise 2: Reaction of Cyclohexadiene and 1,3-Dioxole

Molecular Orbital Diagram

Molecular orbital (MO) diagram for the reaction of cyclohexadiene and 1,3-dioxole (exo). |

Molecular orbital (MO) diagram for the reaction of cyclohexadiene and 1,3-dioxole (endo) |

(Good, but the MOs should be joined up. Otherwise these appear as non-bonding orbitals Tam10 (talk) 16:26, 3 April 2017 (BST))

| MO Representation | Image | Symmetry | MO Representation | Image | Symmetry | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exo | MO 4

LUMO+1 |

|

|

Antisymmetric | Endo | MO 4

LUMO+1 |

|

|

Antisymmetric |

| MO 3

LUMO |

|

|

Symmetric | MO 3

LUMO |

|

|

Symmetric | ||

| MO 2

HOMO |

|

|

Symmetric | MO 2

HOMO |

|

|

Symmetric | ||

| MO 1

HOMO-1 |

|

|

Antisymmetric | MO 1

HOMO-1 |

|

|

Antisymmetric | ||

The exo and endo Diels-Alder between cyclohexadiene and 1,3-dioxole proceed in a similar fashion as the Diels-Alder between butadiene and ethylene in Exercise 1. However, unlike in Exercise 1, the dienophile, 1,3-dioxole, contains two pi electron donating oxygen adjacent to the C-C double bond. This increases the energy of the molecular orbitals of the dienophile, resulting in higher energies HOMO and LUMO of the dienophile relative to neutral ethylene in Exercise 1. As a consequence, the HOMO of the dienophile and the LUMO of the diene are much closer in energy and thus, interact more strongly. This reaction between cyclohexadiene and 1,3-dioxole is said to proceed via inverse electron demand Diels-Alder. The stronger interaction between the HOMO and LUMO results in a faster and more favourable reaction as compared to the neutral electron demand Diels-Alder between butadiene and ethylene in Exercise 1.

Thermochemistry

The energies of the reactants, transition state and product for both the exo and endo reactions are tabulated below. These are obtained from optimization at B3LYP/6-31G(d) level.

| Energy of Reactants (kJ/mol) | Energy of Transition State

(kJ/mol) |

Energy of Product

(kJ/mol) |

Reaction Barrier

(kJ/mol) |

Reaction Energy

(kJ/mol) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclohexadiene | 1,3-Dioxole | Total | |||||

| Exo | -612591.48 | -701187.43 | -1313778.91 | -1313614.33 | -1313845.77 | 164.58 | -66.86 |

| Endo | -612591.48 | -701187.43 | -1313778.91 | -1313622.15 | -1313849.37 | 156.76 | -70.46 |

Both the exo and endo reactions are exothermic. However, it can be seen that the energy of the endo product is lower (or more negative) than the energy of the exo product, and the endo reaction also has a lower reaction barrier as compared to the exo reaction. This means that the endo product is both the thermodynamically and kinetically favourable product. This can be explained by considering both electronic and steric factors

Secondary orbital interactions stabilize the endo transition state, reducing the reaction barrier. On the left is the HOMO of the endo transition state in which there are obvious secondary orbital interactions between the oxygen p orbitals of the 1,3-dioxole and the p orbitals of the diene. An MO representation of this HOMO is shown below.

Steric clash between the sp3 CH2 of the dioxole ring and the sp3 CH2's of the cyclohexadiene destabilize both the exo transition state and the exo product.

Vibration and Reaction Path

| Exo | Endo | |

|---|---|---|

| Vibration |

|

|

| Vibrational Frequency | 520.90i cm-1 | 528.85i cm-1 |

| Reaction Pathway |

|

|

| Mechanism | Synchronous concerted | Synchronous concerted |

Calculation Files

File:TP1414 Exercise 2 Cyclohexadiene 631Gd.log

File:TP1414 Exercise 2 1,2-Dioxole 631Gd.log

File:TP1414 Exercise 2 Exo Product 631Gd.log

File:TP1414 Exercise 2 Endo Product 631Gd.log

File:TP1414 Exercise 2 Exo Transition State 631Gd.log

File:TP1414 Exercise 2 Endo Transition State 631Gd.log

File:TP1414 Exercise 2 Exo IRC 631Gd.log

File:TP1414 Exercise 2 Endo IRC 631Gd.log

Nf710 (talk) 10:49, 7 April 2017 (BST) Good section everything done well. Nice diagrams particularly

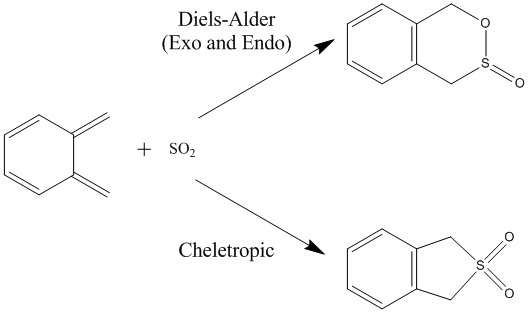

Exercise 3: Diels-Alder vs Cheletropic

Molecular Orbital Diagram

The exo and endo Diels-Alder reaction between o-xylylene and SO2 proceed in a similar fashion as the reactions in Exercise 1 and 2. However, in this case, the dienophile, SO2, is electron-deficient and has lower energies HOMO and LUMO compared to the dienophiles in Exercise 1 and 2. As a result, the most significant frontier orbital interaction is between the HOMO of o-xylylene and the LUMO of SO2. The Diels-Alder reaction between o-xylylene and SO2 proceeds via normal electron demand.

The exo and endo Diels-Alder reaction between o-xylylene and SO2 have another competing pericyclic reaction - cheletropic reaction. Woodward Hoffmann defines cheletropic reactions as pericyclic reactions in which two sigma bonds are formed or broken in a single atom. It is sometimes considered to be a subclass of cycloadditions. [7] The MO diagram for the cheletropic reaction is shown below.

(Very good - you've identified the two orbitals of SO2 involved in the reaction and their symmetries as well. Just be careful that the PM6 orbitals might not represent the system very well Tam10 (talk) 16:26, 3 April 2017 (BST))

Thermochemistry

The energies of the reactants, transition state and product for the exo, endo and cheletropic reactions are tabulated below. These are obtained from optimization at PM6 level.

(You should have the values of the energies on this diagram to make it easier to compare Tam10 (talk) 16:26, 3 April 2017 (BST))

| Energy of Reactants (kJ/mol) | Energy of Transition State

(kJ/mol) |

Energy of Product

(kJ/mol) |

Reaction Barrier

(kJ/mol) |

Reaction Energy

(kJ/mol) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| o-Xylylene | SO2 | Total | |||||

| Exo | 467.99 | -311.42 | 156.57 | 241.75 | 56.31 | 85.18 | -100.26 |

| Endo | 467.99 | -311.42 | 156.57 | 237.77 | 56.98 | 81.20 | -99.59 |

| Cheletropic | 467.99 | -311.42 | 156.57 | 260.09 | -0.01 | 103.52 | -156.58 |

All three reactions are exothermic. The endo product is the kinetically favourable product as it has the lowest reaction barrier, while the cheletropic product is the thermodynamically favourable product as it has the lowest energy. This is consistent with experimental works that have been conducted in which a Diels-Alder adduct is observed to be the kinetic product and cheletropic adduct is observed to be the thermodynamic product. Experimental work shows that the Diels-Alder adduct is thermally unstable and will undergo a retro-Diels-Alder reaction to form back the starting materials, before forming the more stable five membered ring cheletropic product. [7]

(Good. This exercise is only part of the picture. The DA products can even undergo a direct rearrangement to the cheletropic product Tam10 (talk) 16:26, 3 April 2017 (BST))

Vibration and Reaction Path

| Exo | Endo | Cheletropic | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vibration |

|

|

|

| Vibrational Frequency | 351.78i cm-1 | 334.38i cm-1 | 486.58i cm-1 |

| Reaction Pathway |

|

|

|

| Mechanism | Asynchronous concerted | Asynchronous concerted | Synchronous concerted |

| IRC |

|

|

|

It is interesting to note that the exo and endo reactions proceed via asynchronous mechanism in which the C-O bond is formed first before the C-S bond, while the cheletropic reaction proceeds via synchronous mechanism in which the two C-S bonds are formed simultaneously. However, even though the formation of the two bonds are asynchronous in the exo and endo reactions, the total energy along IRC tells us that both reactions are concerted as the reactions do not have any intermediate steps.

(Don't pay too much attention to the 'bonds' that GaussView puts on the atoms. They are only an indication that a threshold distance has been crossed. It is still asynchronous though, as it is asymmetric Tam10 (talk) 16:26, 3 April 2017 (BST))

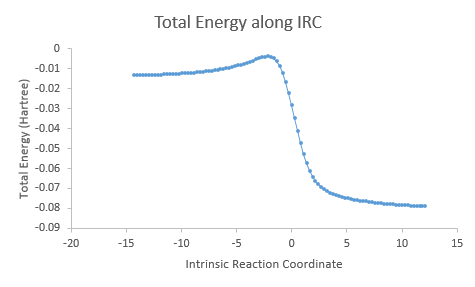

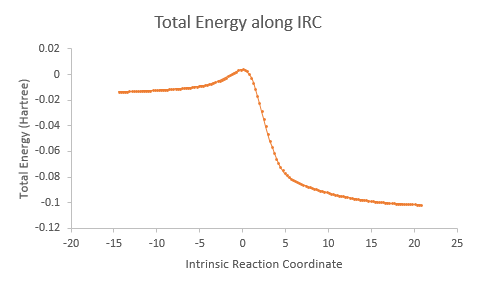

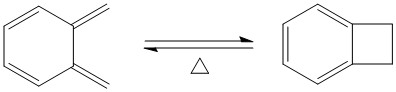

In all three reaction pathways, the steepest part on the the total energy versus IRC graph corresponds to the re-aromatisation of the 6-membered ring on the o-xylylene, giving these reactions an aromatic driving force. This also shows the instability of the o-xylylene molecule. O-Xylylene is highly unstable as it is antiaromatic (planar and 4n electrons), and it will undergo an electrocyclic ring closure to form the stable aromatic isomer, benzocyclobutene as shown below.[9]

A quick transition state optimisation followed by IRC calculation of the above reaction on Gaussian gives the total energy along IRC graph below.

(Good work here too. You should note that this reaction is difficult under thermal conditions. There is a high barrier associated with rotating the methylene groups Tam10 (talk) 16:26, 3 April 2017 (BST))

Alternate Diels-Alder Reaction

There is a second cis-butadiene fragment in o-xylylene that can undergo a Diels-Alder reaction. This second cis-butadiene is part of the cyclohexadiene ring. The exo and endo for this alternate Diels-Alder reaction proceed as follow:

Both reactions proceed via an asynchronous mechanism.

The thermochemistry for this alternate Diels-Alder reaction is as follows:

| Energy of Reactants (kJ/mol) | Energy of Transition State

(kJ/mol) |

Energy of Product

(kJ/mol) |

Reaction Barrier

(kJ/mol) |

Reaction Energy

(kJ/mol) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| o-Xylylene | SO2 | Total | |||||

| Exo | 467.99 | -311.42 | 156.57 | 275.82 | 176.71 | 119.25 | 20.14 |

| Endo | 467.99 | -311.42 | 156.57 | 267.98 | 172.26 | 111.41 | 15.96 |

Comparing the energies for this alternate Diels-Alder reaction with the energies for the normal Diels-Alder and the cheletropic reactions, it can be seen that both the exo and endo alternate Diels-Alder reactoions are kinetically and thermodynamically unfavourable. The products are also higher in energies than the reactants, making the reactions endothermic.

Calculation Files

File:TP1414 Exercise 3 Xylylene.log

File:TP1414 Exercise 3 SO2.log

File:TP1414 Exercise 3 Exo Product.log

File:TP1414 Exercise 3 Endo Product.log

File:TP1414 Exercise 3 Cheletropic Product.log

File:TP1414 Exercise 3 Exo Transition State.log

File:TP1414 Exercise 3 Endo Transition State.log

File:TP1414 Exercise 3 Cheletropic Transition State.log

File:TP1414 Exercise 3 Exo IRC.log

File:TP1414 Exercise 3 Endo IRC.log

File:TP1414 Exercise 3 Cheletropic IRC.log

File:TP1414 Exercise 3 Xylylene Electrocyclic Transition State.log

File:TP1414 Exercise 3 Xylylene Electrocyclic IRC.log

File:TP1414 Exercise 3 Alternate Exo Product.log

File:TP1414 Exercise 3 Alternate Endo Product.log

File:TP1414 Exercise 3 Alternate Exo Transition State.log

File:TP1414 Exercise 3 Alternate Endo Transition State.log

File:TP1414 Exercise 3 Alternate Exo IRC.log

File:TP1414 Exercise 3 Alternate Endo IRC.log

Conclusion

Two calculation methods were used to study three different Diels-Alder reactions. The semi-empirical method PM6 was used to calculate the geometries of the transition state and product of the reactions in all three exercises for faster calculations. In exercise 2, the geometries were further optimised by the DFT method B3LYP at 6-31G(d) level for better accuracy.

Exercises 1 to 3 illustrate the three different ways in which Diels-Alder reaction can proceed: neutral electron demand, inverse electron demand and normal electron demand respectively. In exercise 1, the frontier orbital interactions of the simplest Diels-Alder reaction was studied and it shows that only orbitals of the same symmetry can interact. Exercise 1 also illustrates how internuclear distances vary as a Diels-Alder reaction proceeds, and how these compare with the Van der Waals radii of the atoms. Exercise 2 presents a more complex Diels-Alder reaction which can proceed in two different orientations - endo and exo. It demonstrates how secondary orbital interactions and steric factors could affect the energies of the transition states and products, and hence, determine the kinetically and thermodynamically favourable reactions. Exercise 3 illustrates an even more complex system where there are two diene functional groups and in which another competing pericyclic cheletropic reaction is possible. It also demonstrates that pericyclic reactions can proceed via synchronous concerted or asynchronous concerted mechanisms depending on the symmetry of the interacting molecules.

In conclusion, Gaussian proves to be a useful molecular modelling software to investigate the molecules and their reactions. Transition states were located and characterized, and frontier orbital interactions and thermochemistry were analysed. Results obtained from these calculations also proved to be consistent with theory and experimental observations.

References

- ↑ H. Fehske, R. Schneider and A. Weiβe, Eds., Computational Many-Particle Physics, Springer, Berlin, 2008, pp. 438.

- ↑ Lecture notes: Quantum Mechanics 3/3rd Year Computational Chemistry Laboratory, Michael Bearpark, Imperial College.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 A.-C. Knall and C. Slugovc, Chem Soc Rev, 2013, 42, 5131–5142.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 E. Eibler, P. Hocht, B. Prantl, H. Rormaier, H. M. Schuhbauer and H. Wiest, Liebigs Ann.lRemei, 1997, 1997, 2471–2484.

- ↑ J. M. Hornback, Organic Chemistry, Thomson Learning. Inc., Belmont, Second., 2006, pp. 94.

- ↑ J. Kuriyan, B. Konforti and D. Wemmer, The Molecules of Life: Physical and Chemical Principles, Garland Science, New York, 2013.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 D. Suarez, T. L. Sordo and A. Sordo, J. Org. Chem., 1995, 60, 2848–2852.

- ↑ P. S. Kalsi, Organic Reactions Stereochemistry and Mechanism, New Age International Publishers, New Delhi, Fourth., 2006, pp. 550.

- ↑ G. Mehta and S. Kotha, Tetrahedron, 2001, 57, 626.