Rep:Mod:TKMPHY

Physical Module: Transition states and reactivity

Gaussian 09W, a computer software for computational chemistry, was used to perform all the computational calculations in this computational experiment.

The Cope Rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene

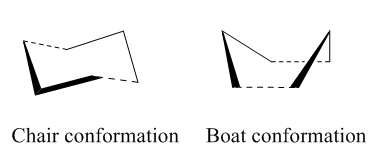

The Cope rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene has been studied intensively and the nature of its reaction mechanism is still controversial. Many experimental and theoretical investigations have been conducted and it is now believe that this reaction is a concerted reaction, where bond breaking and bond forming occurred simultaneously, via a transition state with either a boat or a chair conformation (Figure 1).[1][2] The transition state with a chair conformation is believed to be lower in energy than the boat conformation. This computational exercise has confirmed that the activation energy of the chair transition state (34.07 kcal/mol) is lower than that of the boat transition state (41.98 kcal/mol) at 0K using B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory.

Two different conformations of 1,5-hexadiene were optimized and compared to determine the conformation with the lowest energy. The second part of this section is to optimize a chair and a boat transition state. Optimizations have been performed at 2 different level of theories (HF/3-21G and B3LYP/6-31G*). It is observed that the main difference is that B3LYP/6-31G* optimizes structure to a lower energy.

1,5-hexadiene

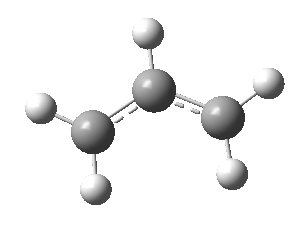

The first part of this optimization exercise is to optimize a molecule of 1,5-hexadiene with a "anti" linkage for the four C atoms. This structure was optimized at the HF/3-21G level of theory. After optimization the electronic energy was calculated to be -231.6925Ha with Ci symmetry point group. By comparing the energy of this molecule to the table in Appendix 1, this structure is equivalent to anti2 (Figure 2).

1,5-hexadiene (Anti) |

Frequency calculation at the HF/3-21G level of theory has been carried out and the results were summarized in Table 1:

| Type of Energies | Description | Energy/Hartrees

HF/3-21G |

|---|---|---|

| Sum of electronic and zero-point energies | The sum of the potential energy at 0K and the zero-point vibrational energy (E = Eelec+ZPE) | -231.5395 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal energies | The energy at 1 atm of pressure and 298.15K, including the vibrational, rotational and translation energy contributions at 298.15K. (E = E + Evib + Erot + Etrans) | -231.5326 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal enthalpies | As above including a correction for RT (H = E +RT) | -231.5316 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal free energies | As above including the entropic contribution to the free energy (G = H - TS) | -231.5709 |

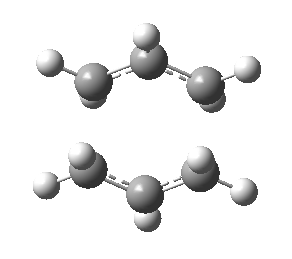

The second part of this exercise is to optimize 1,5-hexadiene with a "gauche" linkage within the C atoms. This structure was also optimized at the HF/3-21G level of theory. The electronic energy of this structure after optimization was calculated to be -231.6927Ha with C1 symmetry point group. This structure is equivalent to the gauche3 structure in Appendix 1 (Figure 3).

1,5-hexadiene (Gauche |

The optimized anti2 structure was then re-optimized at the B3LYP/6-31G* level. The electronic energy was calculated to be -234.6117 Ha which is lower in energy after re-optimization. The symmetry point group is Ci and the change in geometry is not noticeable. Table 2 shows the comparison of the structures of before and after re-optimization.

| Before re-optimization | After re-optimization | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| 1,5-hexadiene optimized at HF/3-21G | 1,5-hexadiene optimized at B3LYP/6-31G* |

The optimized B3LYP/6-31G* structure was then used to run a frequency calculation at the same level of theory. A list of energies have been calculated which is listed in Table 3:

| Type of Energies | Energy/Hartrees

B3LYP/6-31G* |

|---|---|

| Sum of electronic and zero-point energies | -234.4692 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal energies | -234.4619 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal enthalpies | -234.4609 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal free energies | -234.5008 |

Furthermore, an infrared spectrum of this structure was simulated as shown in Figure 4. It is observed that energies calculated using the B3LYP/6-31G* theory are lower than that calculated using HF/3-21G theory.

Transition Structures

Chair Transition State

First of all, an allyl fragment (Figure 5) was optimized at the HF/3-21G level of theory. After optimization, the structure was similar to half of the transition state structure.

After optimization, two of this fragments were used to assemble the chair transition state with the terminal ends of the framgents 2.2Å apart (Figure 6). Two different optimization approaches were then performed.

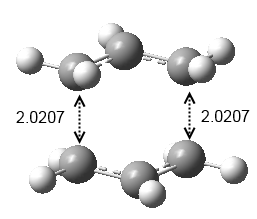

For the first optimization method, the chair transition state was optimized to a TS (Berny) at the HF/3-21G level of theory and frequency calculation was carried out simultaneously. The force constants were calculated once in this approach. The electronic energy was calculated to be -231.6193Ha with C2h symmetry point group and the distance between the terminal ends were 0.0207Å (Figure 7). The sum of energies were calculated and they were summarized in Table 4:

| Type of Energies | Energy/Hartrees

HF/3-21G |

|---|---|

| Sum of electronic and zero-point energies | -231.4667 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal energies | -231.4613 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal enthalpies | -231.4604 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal free energies | -231.4952 |

An Inferred Spectrum of this chair transition state was simulated (Figure 8). An imaginary frequency of magnitude 818 cm-1 was calculated which corresponded to the Cop rearrangement transformation (Figure 9).

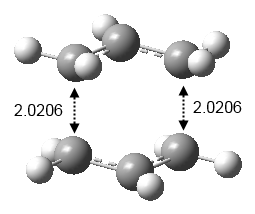

Another approach of optimizing this chair transition state was performed by freezing the bond distance between the terminal ends of the allyl fragments to 2.2Å. The structure was optimized and the electronic energy was found to be -231.6148Ha and the structure was similar to Figure 6 except the distance between the terminal ends were fixed to 2.2Å. This structure was then proceeded to a transition state optimization without calculating the force constants and the distance between the terminal ends were not fixed. The electronic energy was calculated to be -231.6193Ha and the distance between the terminal ends were 2.0206 (Figure 10).

Comparing these two approaches of optimization, they produced the same electronic energy result which was -231.6193Ha and the difference in the calculated distance between the terminal ends were 0.001Å. Thus, both optimization approaches produce very similar results with a small difference in the distance of the terminal ends of the allyl fragments.

The chain transition state was further optimized at the B3LYP/6-31G* level using the Hessian approach. The electronic energy was calculated to be -234.5570Ha and the sum of energies were summarized in Table 5.

| Type of Energies | Energy/Hartrees

B3LYP/6-31G* |

|---|---|

| Sum of electronic and zero-point energies | -234.4149 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal energies | -234.4090 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal enthalpies | -234.4081 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal free energies | -234.4438 |

As expected, the energies calculated at B3LYP/6-31G* were lower than that calculated at HF/3-21G.

Using the data from Table 4 and Table 5, the activation energies of the chair transition state were calculated. The results were summarized in Table 6.

| Activation energy | Energy (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|

| Activation energy at 0K (HF/3-21G) | 45.68 |

| Activation energy at 298.15K (HF/3-21G) | 44.74 |

| Activation energy at 0K (B3LYP/6-31G*) | 34.07 |

| Activation energy at 298.15K (B3LYP/6-31G*) | 33.20 |

Given that the activation energy of the chair transition state was found to be 33.5±0.5 kcal/mol experimentally at 0K, it shows that calculations at B3LYP/6-32G* give a closer value to the experimental data.

Boat Transition State

In order to optimize the boat transition state, a different approach called the QST2 method was used. In this approach, the reactants and the products of a reaction are specified. Calculation will then determine the transition state of the reaction.

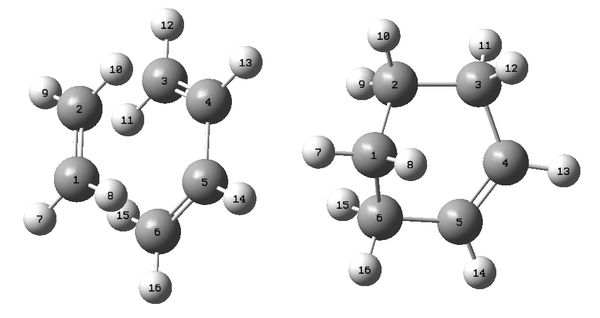

First of all, the atoms of the reactant and product were renumbered manually (Figure 11).

These molecules were then optimized at HF/3-21G using the QST2 calculation. However, using the reactant and product as shown in Figure 11 failed to reassemble the boat transition state. Instead, it produced the chair transition state with C2h symmetry point group (Figure 12). Thus, modification on the geometries of the reactant and product has been made before another optimization attempt (Figure 13). The central C-C-C-C dihedral angles of both molecules were modified to 0o and the C-C-C angles were reduced to 100o.

After the modifications on the geometries of the molecules, the molecules converged into a boat transition structure successfully (Figure 14). The electronic energy was calculated to be -231.6028Ha with C2v symmetry point group. The distance between the termal ends of the of the allyl fragments were calculated to be 2.1400Å. The energies data were summarized in Table 7.

| Type of Energies | Energy/Hartrees

HF/3-21G |

|---|---|

| Sum of electronic and zero-point energies | -231.4510 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal energies | -231.4453 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal enthalpies | -231.4444 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal free energies | -231.4798 |

An Inferred Spectrum of this boat transition state was simulated (Figure 15). An imaginary frequency of magnitude 840 cm-1 was calculated which corresponds to the Cop rearrangement transformation via the boat transition state (Figure 16).

Further investigation was conducted by optimizing the reactant, product and proposed boat transition state with QST3 calculation. The atoms of the molecules were first renumbered as shown in Figure 17 before processing.

This attempt successfully converged the reactant and product molecules into a boat transition state (Figure 18) with the same energies data as using the QST2 calculation. However, the distance between the terminal ends of the allyl fragments were calculated to be 2.1384Å which were slightly closer.

Another optimization attempt has been done by using the QST2 calculation at B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory. The electronic energy was found to be -234.5431Ha with C2v symmetry point group. The energies results were summarized in Table 8.

| Type of Energies | Energy/Hartrees

B3LYP/6-32G* |

|---|---|

| Sum of electronic and zero-point energies | -234.4023 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal energies | -234.3960 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal enthalpies | -234.3951 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal free energies | -234.4318 |

Using the data from Table 7 and Table 8, the activation energies of the boat transition state were calculated. The results were summarized in Table 9.

| Activation energy | Energy (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|

| Activation energy at 0K (HF/3-21G) | 55.60 |

| Activation energy at 298.15K (HF/3-21G) | 54.78 |

| Activation energy at 0K (B3LYP/6-31G*) | 41.98 |

| Activation energy at 298.15K (B3LYP/6-31G*) | 41.35 |

The Diels Alder Cycloaddition

In this computational exercise, all calculations have been done using AM1 semi-empirical molecular orbital method.

Interaction of the π orbitals

Highest Occupied Molecular Orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) are a pair of orbitals of two molecules that are very close in energy. Thus, it is expected that there is a strong interaction between them. The energy difference between the orbitals, the distance between them, their orbital sizes and the symmetry of the orbitals are the factors that affect the strength of the orbital interaction. Orbital interactions depend on their symmetry. Orbital interactions are allowed if the symmetries of the orbitals are compatible with another. The reaction is forbidden if there is a symmetry mismatch between the HOMO-LOMO pair.

Cycloaddition between ethylene and butadiene

Cis-butadiene

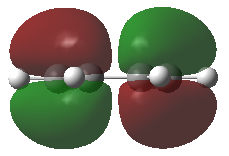

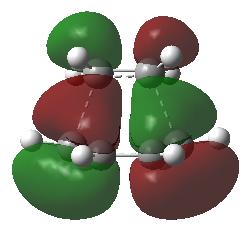

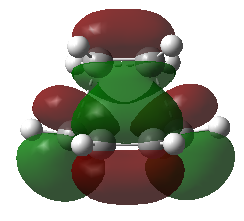

Cis-butadiene has been optimized using the AM1 method and the HOMO and LOMO of this molecule were visualized. The HOMO of of this moleculs is anti-symmetric (Figure 19) while the LUMO is symmetric (Figure 20) with respect to plane.

Transition structure of the cycloaddition reaction between ethylene and butadiene

The QST2 method was used to determine the transition state structure of the cycloaddition reaction between ethylene and butadiene. The atoms of the reactants, ethylene and butadiene, and the product molecules were renumbered as shown in Figure 21 before the QST2 calculation.

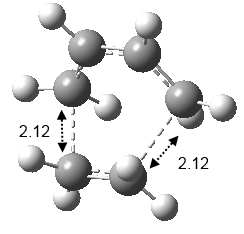

After the QST2 calculation, the transition state structure has been determined (Figure 22). The bond-lengths of the partly formed σ C-C bonds were calculated to be 2.12Å. Typical sp3 and sp2 C-C bond lengths are 1.54Å and 1.47Å respectively. The measured bond distance of the transition structre 2.12Å indicates that there is bond forming interaction between the C atoms as it is within the van der Waals radius 1.7Å of the C atom.[3][4] An Inferred Spectrum of the transition state was simulated (Figure 23) and an imaginary frequency of magnitude 956 cm-1 was calculated which corresponded to the cycloaddition transformation (Figure 24). This animation shows that that formation of the two bonds is synchronous.

The molecular orbitals of this transition structure were visualized. It is observed that there is an anti-symmetrical (Figure 25), and a symmetrical LUMO (Figure 26) exist in this transition structure. Since the HOMO of this transition structure is anti-symmetrical, thus, the anti-symmetrical HOMO of cis-butadiene and the anti-symmetrical LUMO of ethylene must have been used to produce an anti-symmetrical transition state.

The vibration at 147 cm-1 is the lowest positive frequency (Figure 27). The reactants vibrate at the opposite direction as Figure 24. This motion does not correspond to the bonds forming transformation and it is simply the reactants vibrating.

Regioselectivity of the Diels Alder Reaction

In this exercise the cycloaddition between cyclohexa-1,3-diene and maleic anhydride was investigated to study the regioselectivity of the Diels Alder Reaction. It is believed that this reaction mainly yields the endo adduct as product as the endo transition state is lower in energy (-0.0504Ha) than the exo form (-Ha). The computational results have proven that the exo transition state is higher in energy than the endo form.

The exo transition state

The exo transition structure (Figure 28) has been determined using the QST2 calculation. The electronic energy was calculated to be -0.0504Ha. The energies calculated were listed in Table 10.

| Type of Energies | Energy/Hartrees

AM1 |

|---|---|

| Sum of electronic and zero-point energies | 0.1349 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal energies | 0.1449 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal enthalpies | 0.1458 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal free energies | 0.0991 |

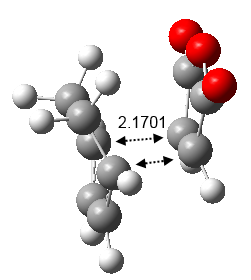

The bond distances of the partly formed C-C bonds are 2.17Å apart and it is observed that the cycloaddition transformation vibration exist at an imaginary frequency of magnitude 812 cm-1 (Figure 30). From this animation it can be seen that the bonds forming transformation is synchronous. This partly formed C-C bonds are longer than a typical C-C bond which indicates that the bonds are forming in this transition state.

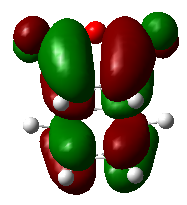

An simulated Infrared Spectrum of this transition structure was generated (Figure 29). The HOMO of this transition stat was visualized (Figure 31).

The endo transition state

The endo transition structure (Figure 32) has been determined using the QST2 calculation. The electronic energy was calculated to be -0.0515Ha which is lower than that calculated for the exo transition structure. The energies calculated were listed in Table 11.

| Type of Energies | Energy/Hartrees

AM1 |

|---|---|

| Sum of electronic and zero-point energies | 0.1335 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal energies | 0.1437 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal enthalpies | 0.1446 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal free energies | 0.0974 |

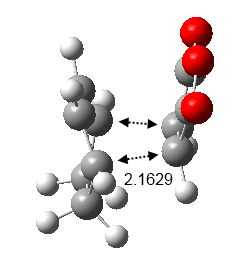

An simulated Infrared Spectrum of this transition structure was generated (Figure 33). The bond distances of the partly formed C-C bonds are 2.16Å apart and it is observed that the cycloaddition transformation vibration exist at an imaginary frequency of magnitude 806 cm-1 (Figure 35). The bonds forming of this transformation is also synchronous.

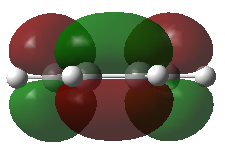

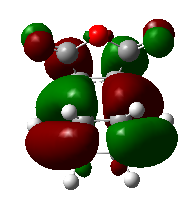

Figure 34 shows the HOMO of the endo transition structure. The endo structure is lower in energy than the exo strucutre due to the secondary orbital overlap effect. Figure 36 indicates that the pi orbitals of the carbon atoms, indicated in green, in the endo structure can overlap which overall stabilize the structure. However, secondary orbital overlap does not exist in the exo structure due to the geometry mismatch.

References

- ↑ Cope, A. C.; Hardy E. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1940, 62, 441.

- ↑ E. Ventura; S. Monte J. Phys. Chem. A. 2003, 107, 1175-1180.

- ↑ J.M.Baranowski "Bonds in carbon compounds" J.Phys.C:Solid State Phys.19(1986)4613-6421,

- ↑ Rowland RS, Taylor R (1996). "Intermolecular nonbonded contact distances in organic crystal structures: comparison with distances expected from van der Waals radii". J. Phys. Chem. 100 (18): 7384–7391,