Rep:Mod:TAB9192

A Computational Study of the Thermodynamic Properties of MgO

Abstract

The volumetric coefficient of thermal expansion () of MgO was computed through the use of both molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and phonon calculations under the quasi-harmonic approximation (QHA). Good agreement between both methods and existing literature was found for temperatures within a range of 100-1000 K. At high temperatures, the MD simulations showed anomalous behaviour in at temperatures between , matching the experimental melting range at closely. The volume at was determined as a function of pressure, and used to calculate the bulk modulus at () of with a pressure derivative of . Again, both MD simulations and QHA-based calculations were performed.

Introduction

Solid MgO adopts the well-known rock-salt structure, which consists of two superimposed but offset face-centred cubic lattices. A detailed theoretical understanding of its thermodynamic properties is paramount to a variety of applications. For example, MgO is a commonly used refractory material, in part due to its chemical stability at high temperatures. In addition, the high-pressure melting of MgO in the earth's lower mantle plays a major role in the seismology of so-called ultra-low velocity zones. However, experimental investigations at such conditions rely on either shockwaves or laser-heated diamond anvil cells, both of which require highly sophisticated equipment and are thus very expensive.[1] A convenient alternative is the use of computational methods. The present work therefore characterises the isothermal compression and thermal expansion of MgO through the use of both MD and QHA-based methods, comparing their accuracy and range of validity.

Methodology

The software used to perform all calculations and simulations was the General Utility Lattice Program (GULP).[2]. DLVisualize [3] was used to provide the user interface.

Lattice Energy of MgO

Both the MD simulations and the phonon calculations under the QHA require a pair potential that determines the inter-particle interactions. Throughout this study, the Coulomb-Buckingham potential was used, taking the following general form:

Where the constants , and are chosen to provide the best match to experimental data, and are shown in table 1.

| Pair | A | B | C | Cutoff / |

| O-O | ||||

| Mg-O |

The cutoff indicates the value of above which the short-range Pauli-repulsion and dispersive potential interactions are discarded (the first two terms of the Coulomb-Buckingham potential). Note that the Coulombic interactions were summed using the Ewald method, where interactions are calculated in Fourier-space, due to its significantly faster convergence for periodic systems [4].

Phonon Calculations under the QHA

Phonons are the collective vibrational modes of a solid. For small distortions from some equilibrium interatomic spacing , the potential can be approximated by a parabola, as can be easily verified by Taylor-expansion around :

Since is a potential energy minimum, , and so, defining yields .

This is the origin of the 'harmonic' part of the QHA. However, this is clearly not a widely applicable model, as the expactation value of the bond length is equal to for all excited states, and so no thermal expansion could take place.

Under the QHA, the Helmoltz free energy per unit cell consists of contributions from the lattice energy (described in the previous section), the zero-point energy of all phonons in the Brillouin zone, and the energy of occupied excited states (including entropic contributions). The latter two of these are averaged over all posible phononic modes, for example by integration over all possible frequencies, weighted by the (normalized) phonon DOS:

The origin of the 'quasi'-part of the QHA is that the volume of the crystal is allowed to vary with a change in conditions in such a way as to minimise the Helmholtz free energy. In general, the force constants of the phonons decrease with increasing volume, and so the vibrational frequencies are lower (a relationship known as Badger's rule [5]). On one hand, this causes the energy of occupied states (the final term) to become more negative and lowers the zero-point energies, but results in a less negative lattice energy for volumes larger than the equilibrium volume at . There are therefore two opposing contributions to the Helmholtz free energy with a change in volume, which will therefore have a minimum at some volume, yielding the equilibrium structure at the given temperature and pressure.

At each volume, this expression is the analytical result derived from the partition function of a harmonic oscillator, averaged over all possible modes. Clearly then, the phonon DOS, , contains all of the information required to calculate the Helmholtz free energy at a given temperature. Computationally, for any real system this integral must be approximated by a summation over a finite number of frequencies, as the phonon DOS cannot generally be determined analytically. The phonon DOS is itself summed over a selection of points in the Brillouin zone, which are determined by the shrinking factors. For a 3D lattice, this is a set of three numbers defining the 'resolution' of a mesh of k-points in the Brilluoin zone at which the phonon DOS is calculated. However, a larger number of sampling points comes with greater computational expense, and so, prior to any studies of the thermodynamic properties of a real system, it is important to determine the convergence of the phonon DOS with the shrinking factor, such that a reasonable compromise between accuracy and speed can be reached. This was assessed both visually from plots of the phonon DOS at different shrinking factors, or by monitoring associated properties such as the Helmoltz free energy.

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are a purely classical approach to modelling the behaviour of systems. The basic principle is that the time evolution of a system obeying Newtonian mechanics is simulated through the use of some iterative algorithm, which integrates the equations of motion at each timestep in order to update the velocities and positions. In this case, the so-called leapfrog algorithm was used, which takes its name from the fact that it offsets the moments in time at which positions and velocities are calculated.

The Coefficient of Thermal Expansion

The thermal expansion of a material can be characterised by its coefficient of thermal expansion:

The division by the volume of the material is required for to be an intensive quantity. This generally varies with temperatue, and can thus be computed by differentiation of a polynomial fit to the volume-temperature data (note hat this renders extrapolation meaningless).[6]

The Bulk Modulus

The isothermal bulk modulus (the inverse of the compressibility) of a material can be obtained by fitting the Birch-Murnghan equation-of-state (BMEOS) to volume-pressure data at constant temperature [7]:

Where is the volume at , is the isothermal bulk modulus in the absence of an external pressure and its pressure derivative.

Results and Discussion

The Total Lattice Energy

The total lattice energy per primitive unit cell was determined to be -41.07531759 eV.

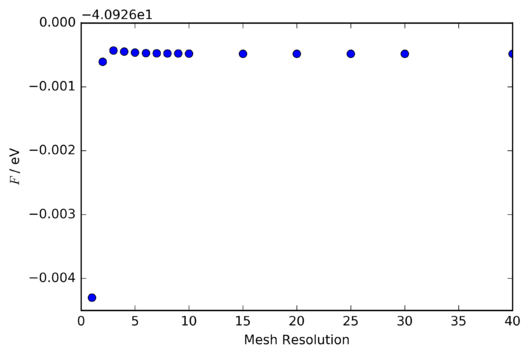

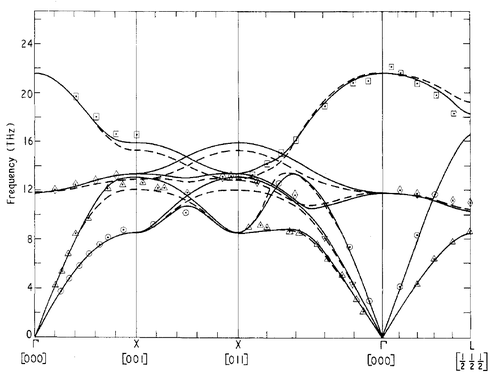

The Phonon Dispersion

The phonon dispersion was calculated at 50 points along the W-L-G-X-W-K path in the Brillouin zone, the graph of which is shown in figure 1. Figure 2 contains an analogous (albeit the path in the first Brilluoin zone somewhat differs) graph derived from neutron scattering data, obtained by Sangster et al. [8]. As can be expected from the general rule that the total number of branches is given by , where is the dimensionality of the system and the number of atoms in the unit cell, there are six branches, since the primitive unit cell contains one Mg and one O ion. In addition, of these branches should be acoustic, in other words, have a minimum at . Clearly, this is also the case.

|

|

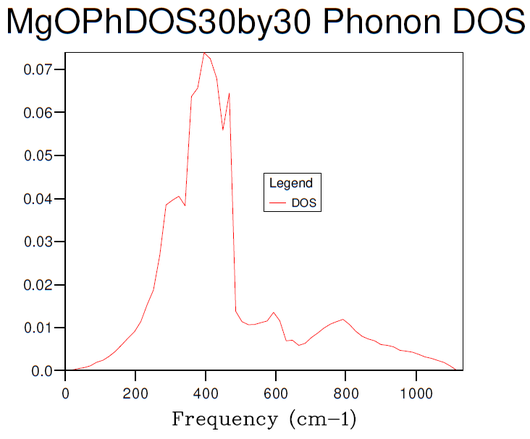

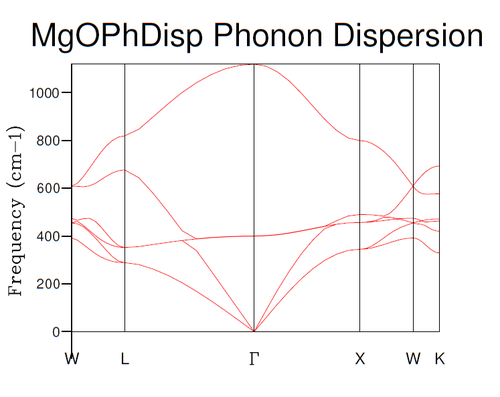

The Phonon DOS

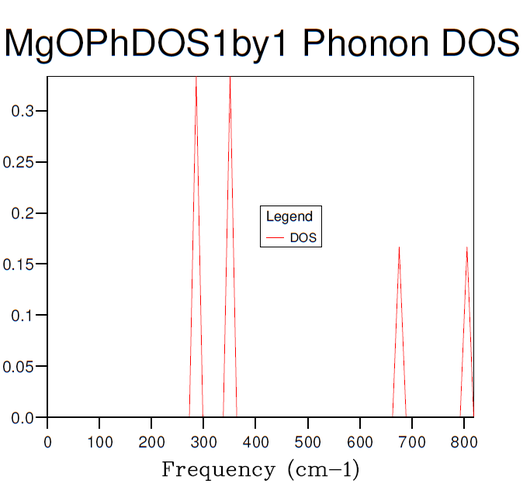

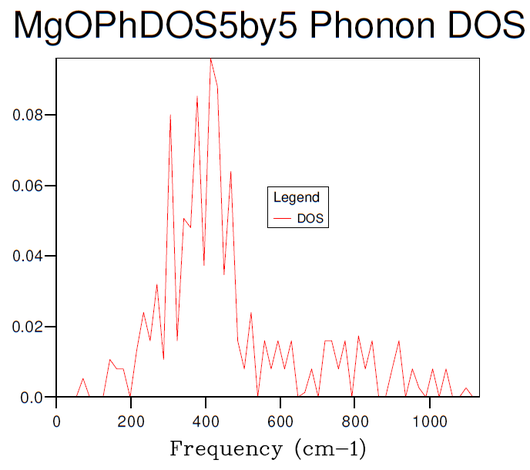

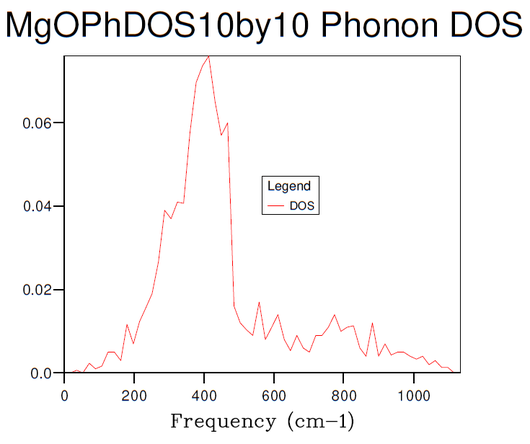

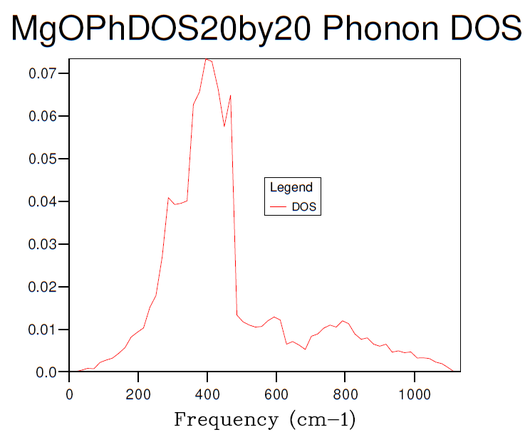

Figures 3-8 illustrate the convergence of the phonon DOS with increasing mesh resolution (shrinking factor). As can be seen, the change in visual appearance (mainly an increase in the smoothness) of the DOS-curve as a result of a change in the mesh resolution decreases with increasing resolution, to the point where there is no significant visual difference between subsequent DOS-curves at resolutions of 30x30x30 and 40x40x40, and so the convergence has satisfied at least the visual criterion.

Comparison of the phonon DOS for evaluated at only a single point in the Brillouin zone (figure 3) with the phonon dispersion curve (figure 1) shows that this point must correspond to the symmetry point L, as this matches the observed frequencies.

In this context, the phonon DOS is defined as the number of states per unit increase in energy at a given energy i.e. . Using the chain rule, this can be rewritten as , where the integral along the surface of arises from the need to consider the contributions of all k-values for which . This expression can of course generally not be computed analytically, but the important thing to note is that the DOS varies inversely with , i.e. the slope of the phonon dispersion curve. In this specific case, the frequency is used in place of the energy, however, the same relationship holds true, as the zero-point energy of a particular phonon mode is given by

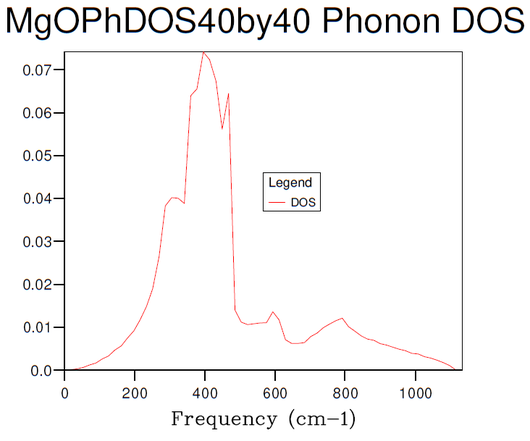

Free Energy in the Quasi-Harmonic Approximation

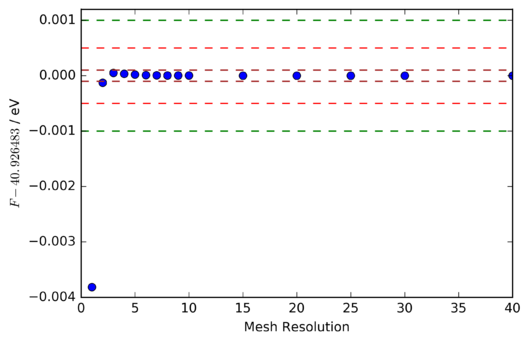

Following the above discussion of the visual convergence of the phonon DOS curve, it should be noted that for the purpose of calculating thermodynamic quantities, it is far more important to know the level of accuracy that can be expected at a given mesh resolution. Thus, the Helmholtz free energy per unit cell of the MgO lattice at was calculated at various mesh resolutions. The results are summarised in table 2 and illustrated in figures 9 and 10.

| Mesh resolution | F/eV | /eV |

| 1x1x1 | N/A | |

| 2x2x2 | ||

| 3x3x3 | ||

| 4x4x4 | ||

| 5x5x5 | ||

| 6x6x6 | ||

| 7x7x7 | ||

| 8x8x8 | ||

| 9x9x9 | ||

| 10x10x10 | ||

| 15x15x15 | ||

| 20x20x20 | ||

| 25x25x25 | ||

| 30x30x30 | ||

| 40x40x40 |

The most distinctive feature of figures 9 and 10 is the rapid convergence of the fractional change in Helmholtz free energy to zero, and that of the Helmholtz free energy itself to a constant value of -40.926483 eV . To investigate the accuracy at each mesh resoltion it is necessary to compare not this change in Helmholtz free energy, which depends also on the choice of shrinking factors at which the free energy was evaluated, but instead the difference between the final converged free energy (taken to be -40.926483 eV) and the free energy at a particular mesh resolution. A plot of this is shown in figure 11.

|

Clearly then, an accuracy of 1 meV and 0.5 meV can be achieved with a 2x2x2 grid, and one of 0.1 meV with a 3x3x3 grid. Whilst the discrepancy between the rapid convergence of the Helmholtz free energy, and the much more obvious changes in the visual appearance of the phonon DOS curve might seem counterintuitive, it is important to note that the energetic contribution (both zero-point and excited-state) from phonons is, particularly at 300 K, very small compared to the lattice energy. Therefore, the Helmholtz free energy can be determined with reasonable accuracy even when the phonon DOS curve does not strongly resemble its converged form.

However, as the calculations were not particularly computationally expensive, a mesh resolution of 40x40x40 was used throughout this investigation, to ensure that a lack of sample points in the Brillouin zone was not a significant contributor to the uncertainty in the final results. This grid size would certainly be appropriate for similar compounds such as CaO. Since the dimension of the first Brillouin zone (BZ) is proportional to , where is the characteristic length of the Wigner-Seitz cell, a material with a considerably larger Wigner-Seitz cell than MgO, such as a Zeolite (e.g. Faujasite), would have a smaller first BZ and thus require fewer sample points over which to evaluate the phonon DOS at similar levels of accuracy, i.e. a smaller mesh resolution. For a metal such as Lithium, another factor comes into play. Namely, the delocalised electrons are able to screen the repulsions between approaching charged ions, resulting in decreased phonon dispersion ('width' of the branches). As a result, the energies of the phonon modes at various k-points are more similar than in an insulator, and so an average over a fewer number of sample points describes the phonon DOS curve with equal accuracy. However, the Wigner-Seitz cell of Lithium is smaller than that of MgO, and so, conversely to the case of a Zeolite, this would tend to increase the mesh resolution required for the same level of accuracy. The question of the balance between these two competing factors is outside the scope of this investigation.

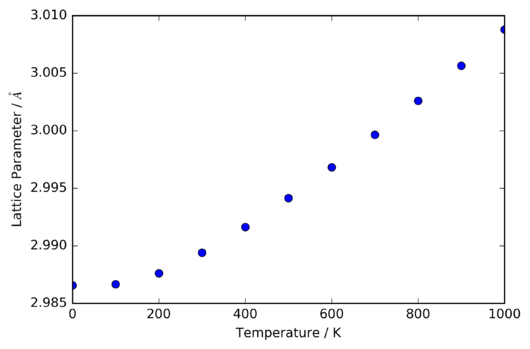

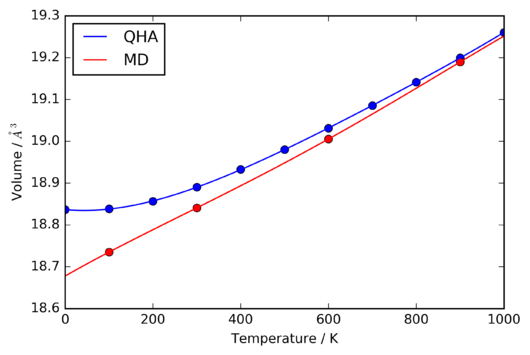

The Thermal Expansion of MgO

Figures 13 and 14 show the behaviour of the lattice parameter (the edge-length of the primitive unit cell of MgO) and the Helmholtz free energy with increasing temperature, as calculated under the QHA.

|

|

As may be intuitively expected, the lattice parameter, and thus the volume of the unit cell, generally increases with increasing temperature. However, at temperatures below ~100 K, there is no significant thermal expansion. To explain this, it is necessary to consider the behaviour of all three terms in the expression of the Helmholtz free energy:

At low temperatures, the last term can be discarded, as the argument of the logarithm approaches unity and is multiplied by the temperature. The observed lack of thermal expansion - and variation in the Helmholtz free energy - at low temperatures is therefore a result of the temperature-independence of the remaining terms. This equation also provides the physical basis for the observed positive thermal expansion. Generally, an increase in volume decreases the values of , decreasing the zero-point energy but increasing the lattice energy. However, it also increases the ability of the system to access higher-lying excited phonon states, the entropic contribution of which is characterised by the last term. At larger temperatures, the contribution of this to the free energy increases, favouring a larger volume.

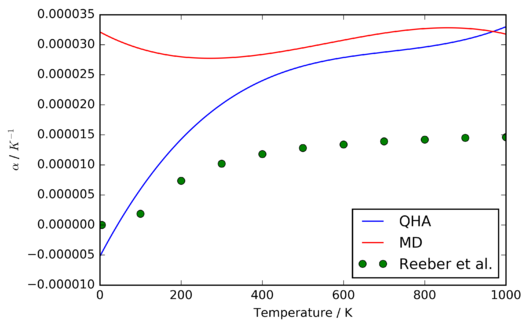

To compute the coefficient of thermal expansion, a fourth-order polynomial was fitted to the volume-temperature data, and its numerical derivative evaluated, from which the coefficent of thermal expansion was then calculated. This analysis was performed for both the data obtained through MD simulations and calculations under the QHA, and the resulting curves of the temperature-dependence of compared to another and to experimental data, as shown in figures 15 and 16. [9]

|

|

As can be seen, the MD simulations do not reproduce the low-temperature tailing observed in the other datasets. This can be attributed to the fact that MD simulations operate exclusively in the realm of Newtonian mechanics, and thus it is no surprise that they fail to account for such fundamentally quantum mechanical effects as the zero-point energy. The agreement between the two methods is better between 400-1000 K, as the zero-point energies become less significant. However, as will be shown later, the discrepancy increases again at temperatures approaching the melting point.

An intruiging feature of figure 16 is that both of the theoretical methods used overestimate the thermal expansion coefficient relative to the experimental data. The most significant approximations used in this investigation are the modelling of MgO as a perfect crystal, and the use of the Coulomb-Buckingham potential to simulate the interatomic interactions. Of these two, the latter is most likely to account for the observed discrepancy (particular at the modest temperatures under consideration), since the defect energy of MgO is very large, and the Coulomb-Buckingham potential ignores the partially covalent character of the Mg-O bond, thus underestimating the bond strength.

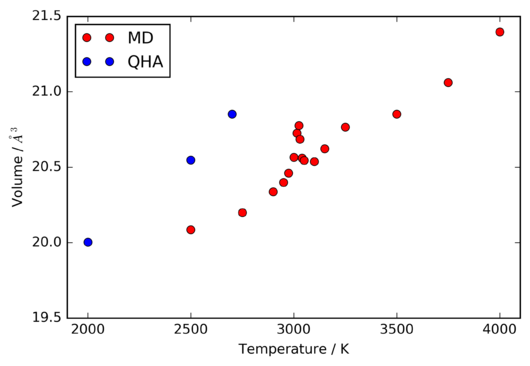

The Melting of MgO

The QHA is inherintly unable to predict the melting of a crystal lattice, since at each volume and temperature, the vibrational potentials are modelled to be harmonic. There is considered to be no thermal motion, and so, whilst the lattice spacing may change, the structure will always be that of a perfect crystal. Thus, the behaviour of the volume of the crystal around the expected melting point of ~ 3000 K. The resulting data from the MD simulations is shown in figure 17.

|

The most notable feature of figure 17 is the onset of large deviations from the otherwise close to linear variation of the primitive unit cell volume with temperature. The similarity of these fluctuations to those observed by Vocadlo et al. [10] , and their occurance at approximately 3025 K, which is very close to the experimental zero-pressure melting range of [11], indicate that they arise from the melting of the crystal lattice.

Interestingly, attempts to perform calculations using the QHA at temperatures above 2700 K did not produce usable data, as the energy did not converge. However, it can clearly be seen in figure 17 that the unit cell volume calculated under the QHA is significantly larger than that derived from the MD simulations at equivalent temperatures, much more so than the systematic discrepancy present in the range of 100-1000 K.

For all MD simulations, a supercell consisting of 2x2x2 conventional MgO unit cells - and thus 32 MgO formula units - was used with periodic boundary conditions. Particularly at larger temperatures, where thermal motion becomes more sinificant, this may result in significant deviations from the behaviour of a perfect infinite crystal. This presents the need for a compromise between computational expense and accuracy, analogous to the shrinking factors used in the phonon calculations under the QHA. It would therefore have been of interest to compare the obtained results with those from MD simulations of larger supercells. However, time constraints did not allow for this to take place.

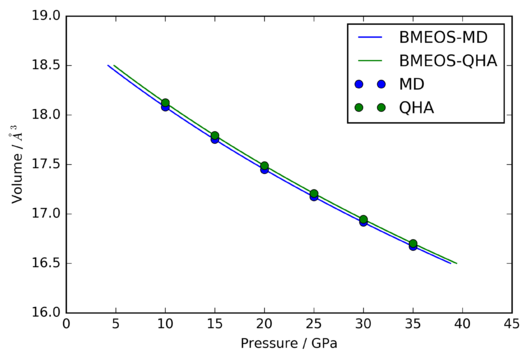

The Bulk Modulus of MgO

The volume-pressure data shown in figure 18 was fitted to the BMEOS, yielding the two curves shown. The resulting values of the Bulk modulus and its pressure derivative at 0 Pa are compared to another and the values obtained experimentally by Rekhi et al. [7] in table 3:

|

| This investigation | Rekhi et al. | |||||

| MD or QHA | / GPa | / | / GPa | / | ||

| QH | ||||||

| MD |

Where the convidence intervals in the calculated parameters correspond to one standart deviation, and were obtained from the covariance matrices of the numerical fits.

Conclusions

In summary, the behaviour of MgO under both changes in pressure and temperature was investigated. First, the convergence of the phonon DOS - calculated under the QHA - with an increasing resolution of sample points in the first BZ, was assessed both visually and by monitoring of the Helmholtz free energy. A mesh resolution of 40x40x40 was then used to calculated the dependence of the primitive cell volume on the temperature, the results compared to those derived from MD simulations, and both used to compute the coefficient of thermal expansion. It was found that MD simulations were able to reproduce the melting of the MgO lattce, whilst calculations under the QHA were not. The bulk modulus of MgO in the absence of pressure was determined through the use of both MD and QHA-based methods, and the results found to be consistent with experimentally measured values.

References

- ↑ Z. J. Liu, X. W. Sun, Q. F. Chen, L. C. Cai, X. M. Tan and X. D. Yang, Phys. Lett. A, 2006, 353, 221–225.

- ↑ J. D. Gale, J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans., 1997, 93, 629–637.

- ↑ B.G. Searle, Comput. Phys. Commun., 137, p. 25 (2001)

- ↑ Ewald, P. P., Ann. Phys., 369: 253–287.

- ↑ J. Cioslowski, G. Liu and R. A. Mosquera Castro, Chem. Phys. Lett., 2000, 331, 497–501.

- ↑ D. K. Smith and H. R. Leider, J. Appl. Cryst. (1968). 1, 246-249

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 S. Rekhi, S. K. Saxena, Z. D. Atlas and J. Hu, Solid State Commun., 2000, 117, 33–36.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 M. J. L. S. and G. P. and D. H. Saunderson, J. Phys. C Solid State Phys., 1970, 3, 1026.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 R. R. Reeber, K. Goessel and K. Wang, Eur. J. Mineral., 1995, 7, 1039–1048.

- ↑ L. Vocadlo and G. D. Price, Phys. Chem. Min. 23, 42-49

- ↑ A. Zerr and R. Boehler, Nature, 1994, 371, 506–508.