Rep:Mod:SLimpBizkit

By: Stefanie Lim CID: 00593047

In the previous two modules, molecular mechanics and force field methods were employed to rationalise the reactivity of certain organic and inorganic systems, with particular focus on the relative energies of the products. However, given that these methods are not suitable for describing systems with changes in bonding or electron distribution i.e. transition states, it is difficult to consider the possibility of reactions under kinetic control. Hence, this module aims to examine transition structures by use of molecular orbital-based methods that numerically solve the Schrödinger equation to generate potential energy surfaces. Once located on the surface, the transition states will be characterised and used to determine the preferred reaction pathway. In addition, the reaction paths and barrier heights on the surface will also be calculated.

The two systems that will be investigated in this module will be:

- the Cope rearragement of 1,5-hexadiene

- the Diels-Alder cycloaddition of ethylene and butadiene

The Cope Rearrangement

In this section, the Cope rearrangement will be examined by analysing the rearrangement of 1,5-Hexadiene via a [3,3]-sigmatropic shift. The exact mechanism by which this proceeds has been the subject of much debate previously[1], both tested with experimental and computational studies. It is now generally accepted, however, that this can occur via one of two possible transition states: the 'chair' or the 'boat' transition structure.

Optimisation of 1,5-Hexadiene

Given the possibility of rotation about the central sp3 C-C linkage, several isomers of 1,5-hexadiene exist in the ground state. Here, a total of 10 isomers of the molecule - 6 gauche and 4 anti - were optimised to determine the three lowest energy conformations. The optimisation was carried out at the HF/3-21G level of theory using Gaussview 9.0, manually manipulating the dihedral angles of the molecules to give the different isomers. The tables below summarise the calculated data for the optimisations of the different conformations.

| Conformer (with LOG file) |

Structure | Point Group | Calculated Energy/Hartrees HF/3-21G |

Lit. Energy/Hartrees HF/3-21G |

Relative Energy/kcal mol-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| anti1 | C2 | -231.69260 | -231.69260 | +0.04 | |

| anti2 | Ci | -231.69254 | -231.69254 | +0.08 | |

| anti3 | C2h | -231.68907 | -231.68907 | +2.25 | |

| anti4 | C1 | -231.69097 | -231.69097 | +1.06 | |

| gauche1 | C2 | -231.68772 | -231.68772 | +3.10 | |

| gauche2 | C2 | -231.69167 | -231.69167 | +0.62 | |

| gauche3 | C1 | -231.69266 | -231.69266 | 0.00 | |

| gauche4 | C2 | -231.69153 | -231.69153 | +0.71 | |

| gauche5 | C1 | -231.68962 | -231.68962 | +1.91 | |

| gauche6 | C1 | -231.68916 | -231.68916 | +2.20 |

It appears from the table above that the three lowest energy conformers at the HF/3-21G level of theory are the gauche3, anti1 and anti2 isomers (the latter ones being higher in energy). Given that the antiperiplanar conformation is energetically preferred over the gauche conformation due to minimal steric repulsion and maximal electron donation into the C-C σ* orbitals, this finding is unexpected. In order to verify this finding, the optimisation was repeated for the lowest three energy conformers, using the more accurate DFT B3LYP/6-31G method.

| Conformer (with LOG file) |

Structure | Point Group | Calculated Energy/Hartrees B3LYP/6-31G* |

Relative Energy/kcal mol-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| anti1 | C2 | -234.61180 | 0.00 | |

| anti2 | Ci | -234.61171 | +0.06 | |

| gauche3 | C1 | -231.61133 | +0.29 |

Contrary to the findings before, the anti1 isomer was calculated to be the lowest energy conformation at this level of theory followed by the anti2 and gauche3 isomers. This is more consistent with stereoelectronic predictions.

Frequency Analysis

To ensure that the success of the optimisation and that a minimised structure has indeed been reached, the vibrations of the molecules were inspected for an imaginary frequencies that would indicate a transition state rather than a minimum. The absence of negative frequencies confirmed the optimisation of the systems.

| Conformer (with LOG File) | Symmetric C=C Stretch | Asymmetric C=C Stretch (cm-1) | Full IR Spectrum | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency (cm-1) | Intensity | Vibration | Frequency (cm-1) | Intensity | Vibration | ||

| anti1 | 1731 | 5 |  |

1734 | 14 |  |

|

| anti2 | 1731 | 0 |  |

1734 | 18 |  |

|

| gauche3 | 1732 | 7 |  |

1733 | 6 |  |

|

The IR spectra of the molecules all display the expected absorptions for unsaturated hydrocarbon chains. The absorption of interest is the symmetric and antisymmetric C=C stretches of the system. As shown above, depending on the system being examined, the intensity of the absorption varies. This can be attributed to the symmetry of the molecule. For highly symmetrical systems, such as the anti1 conformer of the Ci point group, the IR absorption intensity can be expected to be low given that changes in the dipole moment of the system will tend to be smaller. This is observed above with the least symmetric system - anti2 - resulting in the strongest IR absorptions. Another observation to note is the frequency of the absorptions. The asymmetric C=C stretch frequencies are experimentally found to be higher than that for the symmetric stretch[2]. However, the calculated frequencies seem to suggest very similar frequencies for these two motions. This inconsistency may be due to errors in the computational methods employed to model the system, which must be taken into account when analysing calculated data.

Thermochemistry Analysis

Thermochemical Data at 298.15 K: anti1 conformer: Sum of electronic and zero-point Energies= -234.469284 Sum of electronic and thermal Energies= -234.461962 Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies= -234.461018 Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies= -234.500164 anti2 conformer: Sum of electronic and zero-point Energies= -234.469203 Sum of electronic and thermal Energies= -234.461856 Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies= -234.460912 Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies= -234.500778 gauche3 conformer: Sum of electronic and zero-point Energies= -234.468693 Sum of electronic and thermal Energies= -234.461464 Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies= -234.460520 Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies= -234.500105

Thermochemical Data at 0K: anti1 conformer: Sum of electronic and zero-point Energies= -234.469284 Sum of electronic and thermal Energies= -234.469284 Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies= -234.469284 Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies= -234.469284 anti2 conformer: Sum of electronic and zero-point Energies= -234.469203 Sum of electronic and thermal Energies= -234.469203 Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies= -234.469203 Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies= -234.469203 gauche3 conformer: Sum of electronic and zero-point Energies= -234.468693 Sum of electronic and thermal Energies= -234.468693 Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies= -234.468693 Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies= -234.468693

Optimisation of the Transition State

As illustrated in Figure 1, the Cope rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene proceeds via one of two possible structures: the 'chair' or the 'boat' transition states. In an attempt to investigate these two reaction pathways, the transition structures will be optimised and the reaction coordinate visualised by running the IRC (Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate) for both geomtries. Once complete, the activation energies of the two transition states will be then calculated to determine the preferred method of reaction.

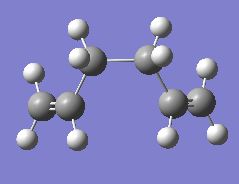

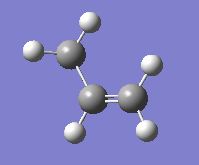

In this section, both the 'chair' and 'boat' transition structures are modeled as two optimised allyl fragments located approximately 2.2 Å. As shown in Figures 2 and 3, the 'chair' geometry possesses C2h while the 'boat' geometry has C2v symmetry. The optimisation of these two structures were performed using the three methods given below:

- Computation of the force constant matrix (i.e. the Hessian) at the first step of the optimisation

- Freezing of the reaction coordinate using the redundant coordinate editor

- Use of the QST2 method

In addition to rationalising the reactivity of the Cope rearrangement, this section aims to examine the ability and accuracy of the above computational methods in modelling the 1,5-hexadiene system.

|

|

Optimisation of the Chair TS

For this transition structure, the optimisation was performed using both methods 1 and 2 at the HF/3-21G level of theory. It should be noted that before each method was carried out, the allyl fragments were positioned so that the system roughly resembled the chair conformation, with the fragments spaced approximately 2.2 Å apart.

Method 1: Computation of the force constant matrix

Unlike the structure minimisations performed in Modules 1 and 2, transition state optimisations are more difficult due to the fact that the direction of the reaction coordinate needs to be determined, particularly for symmetrical surfaces such as that given here. Generally, the easiest way to do this is to calculate the force constant matrix (the Hessian) in the first step of the optimisation process. However, this method is only effective if a reasonable geometry for the transition state can be first obtained. It is for this reason that the allyl fragments were manually positioned to resemble the 'chair' transition state before the optimisation was carried out.

Once arranged, a Opt+Freq Gaussian calculation was set up, selecting the Optimisation to a TS (Berny) and calculate force constants Once options, and ran on the HPC servers. The additional keyword, Opt=NoEigen was also included to stop the optimisation process if more than one imaginary frequency is found as more than this would indicate reaching a false maximum on the potential energy surface. The optimised TS and a summary of the calculation can be found in the table below.

|

|

The near-zero value of the RMS gradient supports the successful optimisation of the transition state, given that a maximum on the potential energy surface would result in an ideal gradient (first derivative) of zero. However, it must be remembered that a minimum on the surface can also result in a near-zero RMS gradient. Hence, to verify that a maximum and, thus, a transition state, has indeed been reached, the frequency calculations were inspected. As predicted[3], one imaginary frequency at -818 cm-1 was found (corresponding to the Cope rearrangement shown in the animation below), confirming the optimisation.

Method 2: Freezing the reaction coordinate

As mentioned previously, calculation of the force constant matrix is only effective if the structure of the system before optimisation is similar to the exact structure of the transition state. In cases where this is not applicable, an alternative optimisation of the transition structure can be carried out by freezing the reaction coordinate and minimising the rest of the molecule. This can be done by inclusion of the additional keyword Opt=ModRedundant in the calculation set-up and use of the Redundant Coordinate Editor. For the system here, the terminal carbons on the allyl fragments were set to remain at a distance of 2.2 Å while the rest of the molecule was minimised. Once complete, the structure of the system is likely to be close to the true transition geometry and can, therefore, be subjected to a transition structure optimisation.

One advantage of this method is that the Hessian does not need to be calculated fully before the optimisation can proceed, which is particularly useful for systems where these computations are expensive and time-consuming. Instead, the method differentiates along the reaction coordinate and then makes a guess at the initial force constant. Hence, upon setting up the Gaussian calculation for the system being studied here, the option to calculate the force constants as Never is selected. The optimised TS and a summary of the calculation can be found in the table below.

|

|

As illustrated in the 3D model of the optimised TS, the two allyl fragments are spaced at the same distance as the TS optimised by calculation of the force constant. This, along with their similar energies, suggests that the same optimised transition structure has been generated, which is expected given that the system is relatively simple. For more complex molecules, however, this may not be the case and may be dependent on whether the structure of the transition state can be approximated prior to minimisation.

Inspection of the frequencies of the transition structure indicated one imaginary frequency at 818 cm-1, which is consistent with that found in Method 1. Again, this corresponds to the Cope rearrangement, which can be seen in the animation provided below.

Optimisation of the Boat TS

In contrast to the 'chair' TS, this section employs the QST2 (Quadratic Synchronous Transit) method to optimise the 'boat' transition structure at the HF/3-21G level of theory. This technique is different to the previous two methods in that it requires structures of both the reactants and the products as inputs to find the transition state whereas Methods 1 and 2 use an approximate structure of the transition state which is optimised as the calculation moves along the reaction coordinate. Given that the QST2 method interpolates between the reactant and product structures to find the TS, it is important that the numbering of the atoms in both molecules is kept consistent before and after the rearranegement. This was done manually on the optimised anti2 molecule, as shown below.

|

|

One important thing to note, however, is that, like Methods 1 and 2, the QST2 method often fails if the input structures of the reactant and product molecules are far from the transition structure. Given that the 'boat' TS is the focus of this section, it can be seen that if a QST2 optimisation is submitted of the anti2 molecules in the conformation given above, the calculation is likely to fail due difference in structures. This is indeed what was found.

As shown above, the QST2 optimisation resulted in a transition structure that resembles the 'chair' TS more than the desired 'boat' geometry. This is due to the fact that the method merely translates the allyl fragments, without consideration of C-C bond rotation about the central carbon linkage. To rectify this, the reactant and product molecules were manually manipulated so as to resemble the 'boat' structure more closely. This was done by setting the central dihedral angle to 0° and reducing the C-C-C bond angles on either side of the central linkage to 100°, as shown in the table below. Another QST2 calculation was submitted with these input structures, optimising to a TS(QST2), which generated the correct 'boat' transition structure. Note: there appears to be a bug in the .mol file of the optimised structure; however, the 'boat' geometry is still evident.

|

|

|

|

As done in Methods 1 and 2, the frequency of the molecule was inspected to confirm the location of a transition state. The presence of one imaginary frequency at 841 cm-1 verifies the optimisation of the 'boat' transition structure. Again, given that the imaginary frequency corresponds to the motion along the reaction coordinate from the TS, the fact that this frequency is of the Cope rearrangment supports the mechanism of the reaction.

Visualising the Reaction Coordinate

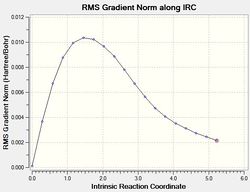

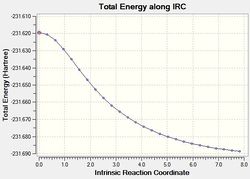

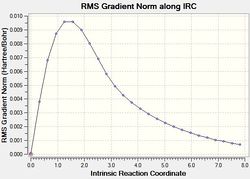

As shown in the first section of this Module, 1,5-hexadiene can adopt numerous conformations due to rotation about C-C bonds. However, given the optimised 'chair' and 'boat' transition structures, it is impossible to predict which conformer the transition state will lead to as it travels down the reaction coordinate onto the formation of the products. Fortunately, the IRC (Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate) method in Gaussian determines the minimum energy reaction pathway from the transition state to the local minimum on the potential energy surface. This is done by taking small iterative steps from the transition state in the direction of the steepest gradient while optimising the structure of the system. Hence, the IRC method ideally generates a system with a gradient of zero at the beginning of the calculation - corresponding to the transition state being a maximum on the surface - as well as at the end with the product molecule as a minimum.

Given that both the reactant and product molecules for this reaction have the same structure, the potential energy surface for the system can be assumed to be symmetric. Hence, upon set-up of the IRC calculation in Gaussian, the reaction coordinate is selected to be computed only in the forward direction. In addition, the force constant was set to be computed once at the start (to save on the calculations) and the number of steps to be taken was changed to 50.

IRC of the Chair TS

|

|

|

|

As shown in the IRC gradient plot, the non-zero gradient of the last step of the calculation indicates that a minimum geometry has not been reached. In an attempt to rectify this, another minimisation was run on the geometry of the last point on the IRC, as this approach would be the fastest solution.

|

|

From the resultant energy shown in the calculation summary, it appears that the product generated from the TS using the IRC is the gauche2 conformer (refer to previous section for comparison). Given that the gauche3 conformer was found to be the lowest energy conformation in the previous section, the fact that the IRC calculation suggests that the pathway to the gauche2 conformer is the lowest in energy is unexpected. This may be due to the fact that the gauche2 structure resembles the transition state more closely than that of the gauche3 conformer.

IRC of the Boat TS

Despite the fact that the structure of the product was specified previously in order to optimise the 'boat' TS, an IRC calculation was run nonetheless to verify the structure of the product.

To check whether the IRC calculation has reached a minimum geometry, the RMS gradient plot was inspected and found to a have a non-zero final value. This suggests that the system has not been fully optimised yet. Hence, the geometry of the last point of the calculation (Figures x and x) was taken and subjected to a normal optimisation. The resultant structure appeared to be very similar to that found after the IRC calculation, only with a longer terminal carbon-carbon length. Thus, the calculation summary was checked to view the RMS gradient and energy of the system. While the RMS gradient was very close to zero (suggesting a successful optimisation), the energy of the system did not correspond to any of the energies of the conformers of 1,5-hexadiene calculated previously. Upon rotation of the molecule, it was noted that the both the 'optimised' geometry and that after the IRC calculation had the same symmetry (Cs). Thus, it was suggested that optimisation calculation was restricted to a ridge in the potential energy surface - with a gradient of zero - that corresponds to Cs symmetry group. In order to get to the minimum on the surface i.e. the product of the rearrangement, the structure of the intermediate geometry was altered slightly to break the symmetry of the system. The modified molecule was then resubmitted to SCAN to run an optimisation. The resultant geometry, as shown below, now resembles that of the gauche3 conformer. To ensure that this was indeed the generated conformer, the calculation summary was inspected and the energy of the system was found to be consistent with that previously calculated for the gauche3 conformer.

|

|

Calculating the Activation Energies

In order to predict which the transition structure is preferred, the activation energies for the Cope rearrangement via both transition states were determined. This was done by calculating the energy difference between the reactant molecule and the transition state, given that both structures were optimised at the same level of theory. As the energies of both the 'chair' and 'boat' transition states have been calculated at the HF/3-21G level, these structures were re-optimised using the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level for comparison. A summary of the activation energies (and the .fchk files for the transition states) is provided in the tables below.

| Transition Structure | Energy / Hartrees HF/3-21G |

gauche3 Energy / Hartrees HF/3-21G |

Activation Energy / Hartrees | Activation Energy / kcal mol-1 | Expt. Activation Energy / kcal mol-1 at 0K |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chair | -231.61932 | -231.69266 | 0.07334 | 46.02156 | 33.5 ± 0.5 |

| Boat | -231.60280 | -231.69266 | 0.08986 | 56.38801 | 44.7 ± 2.0 |

| Transition Structure | Energy / Hartrees B3LYP/6-31G(d) |

anti1 Energy / Hartrees B3LYP/6-31G(d) |

Activation Energy / Hartrees | Activation Energy / kcal mol-1 | Expt. Activation Energy / kcal mol-1 at 0K |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chair | -234.55698 | -234.61180 | 0.05482 | 34.40008 | 33.5 ± 0.5 |

| Boat | -234.54309 | -234.61180 | 0.06871 | 43.11619 | 44.7 ± 2.0 |

It should be noted that the activation energies were calculated based on the energies of two different conformers, depending on the level of theory used. This is due to the fact that the lowest energy conformer is likely to be the most populated conformation and can, therefore, give the most accurate description of the activation energy of the reaction. In the HF/3-21G level of theory, it is found that the gauche3 conformer is the minimum energy conformation whereas in the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level of theory, the lowest energy conformation is the anti1 conformer.

As evident from the results above, it is clear from both levels of theory that the reaction via the 'chair' transition state is the lower energy pathway, suggesting that this would be the preferred reaction mechanism under kinetic control. Thus, it can be predicted that the major conformation for product of the Cope rearrangement will be the gauche2 conformer, as demonstrated by the IRC of the 'chair' TS. Additionally, it can be seen that while both levels of theory generally agree with the experimental activation energies, the B3LYP/6-31G(d) method appears to generate closer values. This may be due to the fact that 6-31G(d) is a higher basis set than 3-21G and, thus, more accurately models chemical systems.

Conclusion

As calculated previously, the three lowest energy conformers for 1,5-hexadiene at the HF/3-21G level of theory are the gauche3, anti1 and anti2 conformers. However, at the B3LYP/6-31G* level, the anti1 isomer is found to be the lowest energy conformer, which is as expected given the stereoelectronic preference for the antiperiplanar conformation over the gauche conformation. With regards to the transition state of the system, it was found that the 'chair' transition state lies approximately 8.7 kcal mol-1 below the 'boat' transition structure, suggesting this as the preferred reaction pathway for the Cope rearrangement. By visualing the reaction coordinate via IRC calculations, the major product of the rearrangement is predicted to be the gauche2 conformer, given that the structure of this isomer resembles the geometry of the transition state the most.

The Diels-Alder Cycloaddition

The Diels-Alder reaction is one of the most powerful synthetic tools, involving the reaction of a conjugated diene with a C-C multiple bond to yield an unsaturated 6-membered ring system[4]. It is widely accepted that this occurs via a cycloaddition process where the π orbital systems of the two substrates overlap and interact to result in the formation of new σ bonds. More specifically, this interaction involves the HOMO/LUMO of the two reactive fragments. Hence, the reactivity of a system can be tuned by altering the substituents on the diene or dienophile, depending on the electronic effects on the HOMO/LUMO. This gives rise to the selectivity of the Diels-Alder cycloaddition, which renders it as one of the most useful reactions within organic chemistry.

In this section, the transition state geometries of two different systems will be calculated in order to examine the nature of the reaction pathways. The first system is the prototypical reaction of butadiene with ethene in order to study the basic principles governing the reaction. Given that neither the diene or the dienophile have any substituents, this is the simplest Diels-Alder system and, thus, simplifies the calculations required to characterise the transition state. The second system involves the reaction between cyclohexa-1,3-diene and maleic anhydride to investigate the regioselectivity of the the reaction, given the presence of substituents on the reactive substrates. Both systems will be analysed using semi-empirical computational methods as well as the DFT method used previously to examine the Cope rearrangement.

The Reaction of Ethene with Butadiene

As shown in Figure x, butadiene and ethene undergo a [4+2] cycloaddition to form cyclohexene via an envelope transition structure that maximises the overlap between the π orbital systems of the two fragments. Given the absence of substituents on either of the molecules, it can be assumed that the interaction of interest will be that of the HOMO and LUMO of the system. Thus, in order to examine the reaction pathway, it is necessary to analyse the interactions.

Optimisation of the Reactants

Before attempting to observe the transition structure of the cycloaddition, butadiene and ethene were optimised using the AM1 semi-empirical method. Then, for comparison, given that B3LYP/6-31G(d) was found to agree well with experimental data in the previous section, this method was also used as a separate optimisation. The HOMOs and LUMOs of the two molecules, after the optimisation, are given in the table below (note that these images were taken looking along the reflection plane of the system).

AM1 Optimisation

|

|

| Butadiene optimisation |

It is evident from the tables above that the HOMO and LUMO of butadiene possess the same symmetry as the LUMO and HOMO of ethene respectively, thus, allowing these pairs of orbitals to interact. Given that the Diels-Alder cycloaddition is thought to proceed in a concerted (symmetry allowed) fashion, these orbital pairs rationalise the observed reactivity of the system.

DFT B3LYP/6-31G(d) Optimisation

For comparison, the optimisation and MO analysis for the starting substrates were also carried out using the DFT B3LYP/6-31G(d) method.

|

|

| Butadiene optimisation |

While the resultant energies of the system are different to those calculated previously - which is expected given that the methods take different factors into consideration - the computed MOs of the two fragments are consistent with that obtained by the AM1 method. This supports the facile reactivity of the two substrates.

Optimisation of the Transition State

Once the HOMO/LUMO pairs for the reactant molecules were computed and found to be of the same symmetry, the transition state of the system was examined. This was done first by approximating the proposed envelope structure and optimising this geometry to a minimum using the freeze coordinate method used previously. Once minimised, the structure was then optimised to a TS (Berny), the frequencies of the structure obtained and the HOMOs and LUMOs computed. As before, given that the resultant structure corresponds to the transition state of the system, only one imaginary frequency is expected, which is due to the motion along the reaction coordinate. Both the AM1 semi-empirical method and the DFT B3LYP/6-31G(d) methods were used for this section.

AM1 optimisation

|

|

|

|

| Antisymmetric | Symmetric | Imaginary frequency: -956 cm-1 |

B3LYP/6-31G(d) optimisation

Unlike the optimisation of the reactants, the computed HOMO/LUMOs of the transition state were found to vary depending on the chosen computation method. Upon further inspection of the HOMO-1 of the TS in both methods, it became evident that the HOMO computed using the AM1 method corresponds to the HOMO-1 of B3LYP/6-31G(d) method and vice-versa. This is illustrated in the table below. This change in the MOs may be attributed to the fact that these two MOs are close in energy and, thus, depending on the method chosen, might be interchanged.

However, despite this inconsistency, it can be seen that the electron density is focused along the carbon framework involved in the cycloaddition. The AM1 HOMO, in particular, illustrates the σ bond formation, connecting the two fragments together. Additionally, the symmetry of the AM1 HOMO of the transition state is consistent with that of the butadiene HOMO/ethene LUMO, suggesting that it is this pair of orbitals that overlap to form the TS HOMO. Similarly, the ethene HOMO/butadiene LUMO has the same symmetry as the LUMO of the transition state.

Despite the difference in the MOs, it can be seen that both methods result in one imaginary frequency that corresponds to the same motion along the reaction coordinate from the transition state (as shown by the animations). This motion is consistent with the proposed bond formation along the terminal carbons of the two fragments. The difference in frequencies is likely to be due to the difference in the computational methods used.

|

|

| Symmetric | Antisymmetric |

The Reaction of Cyclohexa-1,3-diene with Maleic Anhydride

Unlike the reaction of butadiene with ethene, the presence of substituents on both the diene and dienophile introduces regioselectivity issues upon the cycloaddition that were not present previously (see Fugre 48). Here, maleic anhydride can approach cyclohexadiene either above or below the plane of the molecule, resulting in either the endo- or exo-product. It is found experimentally that this reaction is performed under kinetic control to produce the endo-product. This it can be expected that the transition structure for the endo-pathway would be higher in energy than the exo-transition state.

To verify this, the transition states of the reaction were analysed using MO analysis at the AM1 level of theory.

Optimisation of the Reactants

The optimisation of the reactants were carried out as done for the previous system.

|

|

| Cyclohexadiene optimisation |

As shown by the symmetry of the HOMOs and LUMOs of the reactants, the fragment MOs have the same symmetry as those in the previous section for butadiene and ethene, thus, illustrating why the reaction between the two substrates is facile. Once optimised, these fragments were used to examine the endo- and exo-transition structures of the system at the same level of theory.

Optimisation of the Transition State

As evident from the calculation summaries, it is clear that the endo transition state is the lower of the two structures, supporting the experimentally observed preference for the endo-product, as predicted.

References

- ↑ O. Wiest, K. A. Black, K. N. Houk, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1994, 116, 10336; DOI:10.1021/ja00101a078

- ↑ http://www2.chemistry.msu.edu/faculty/reusch/VirtTxtJml/Spectrpy/InfraRed/infrared.htm

- ↑ M. Bearpark, Third Year Computational Lab Module 3, https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=Mod:phys3

- ↑ O. Diels, K. Alder, Liebigs Ann., 1928, 460, 98-122; DOI:10.1002/jlac.19284600106