Rep:Mod:SL8514

Introduction

Chemical Reactions and Potential Energy Surfaces

In a conventional 2D reaction energy profile (Fig. 1), one can imagine the transition state as a structure with maximum free energy linking the two minima that represent the reactants and products. However, in chemical systems of interest, there are usually more than one degrees of freedom in the reaction that can serve as the reaction coordinate, requiring a higher-dimensional plot that captures all the degrees of freedom involved in a reaction.

This is the potential energy surface, which is an important concept in Computational Chemistry and reaction modeling. As the potential energy surface can be seen as a higher-dimension extension of the 2D reaction profile, the same principles apply - reactants and products represent minima on the potential energy surface, and transition states are maxima that links two minima together. Due to the increased number of dimensions, the definition of transition states must be further refined as a first-order saddle point on the potential energy surface (Fig. 2). This means that it must be a minima in any other direction except for the direction of the reactant coordinate, ensuring the presence of a lower-energy "channel" (see Fig. 2) where the molecule must flow through. In quantum mechanical simulations, minima are defined by having positive second derivatives of the Hessian in every direction, while first-order saddle points are defined by having positive second derivatives in every direction except for the direction of the reaction coordinate, where the derivative is positive.[2]

In calculations by the Gaussian software package, frequency analysis allows definitive determination of the transition state by affording a negative vibrational mode on transition state structures that traces the predicted path of the reaction.[3]

Nf710 (talk) 17:35, 21 March 2017 (UTC) This is a well written an understood section however, the force constants are the eigenvalues of the hessian matrix. Not the derivatives of the matrix. The hessian is a matrix of second derivatives.

Diels-Alder Reactions

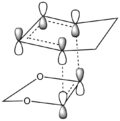

Diels Alder Reactions are [4+2] cycloaddition between a diene and dienophile (usually an alkene with electron-donating or electron-withdrawing groups). The exercises included below are all examples of Diels-Alder reactions. These reactions are usually kinetic and controlled by orbital symmetry. [4]

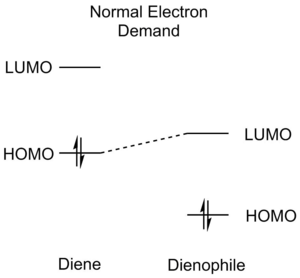

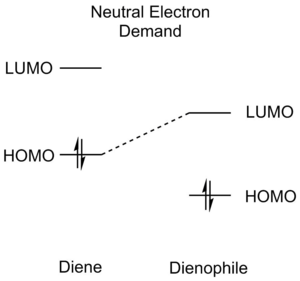

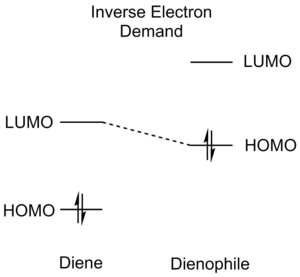

Diels-Alder reactions can be divided into three different categories according to the relative energies of the reactant orbitals - normal electron demand, neutral electron demand an inverse electron demand. An illustration of the relative orbital energies involved is afforded below (Table 1):

EWG on dienophile EDG on diene |

Similar substituents on both |

EDG on dienophile EWG on diene |

|---|

Normal Electron Demand Diels-Alder reactions are characterised by favourable HOMOdiene-LUMOdienophile interactions and the opposite is true for Inverse Electron Demand reactions (HOMOdienophile-LUMOdiene). Normal Electron Demand Diels-Alder reactions are normally faster than Neutral Electron Demand Diels-Alder reactions, which have larger gaps between the diene and dienophile orbitals. As Diels-Alder reactions are usually orbital-controlled, favourable orbital overlaps are very good predictors of more facile reactions.[5][4]

Computational Aims

This computational experiment aims to model three different Diels-Alder reactions - butadiene/ethylene (Exercise 1); 1,3-dioxole/cyclohexadiene (Exercise 2) and SO2-1,2-dimethylenebenzene (Exercise 3). In addition, an alternative cheletropic pathway in the SO2-1,2-dimethylenebenzene reaction is explored and compared with the Diels-Alder reactions.

Methods and Basis Sets used

For all three exercises, product structures were first optimised to minima. Afterwards, bonds formed during the reaction were removed and fragments were edited to resemble reactants. These were moved apart and the structure was frozen into a "Guess Transition State" and optimised to a minima, followed by optimisation to a transition state after removal of redundant coordinates. Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC) calculations were then performed to visualise the entire reaction path.

Calculations in Exercise 1 and 3 were performed with the semi-empirical PM6 method[6], which offers a reasonable amount of accuracy and a much faster computational time. Calculations in Exercise 2 was first performed with PM6, and then further optimised with the hybrid functional density functional theory B3LYP/6-31G(d)[7][8][9][10] basis set. All transition state calculations were performed with the opt=noeigen keyword and the ultrafine grid. In all non-transition state structures, good convergence was observed and no imaginary frequencies were found. In all transition-state structures, good convergence was observed and one imaginary frequency corresponding to the predicted reaction trajectory was found.

Exercise 1: Reaction between Butadiene and Ethylene

The reaction documented above is the simplest possible Diels-Alder reaction. This reaction is modeled with the semi-empirical PM6 method.

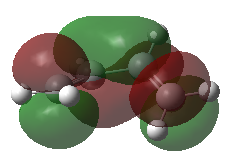

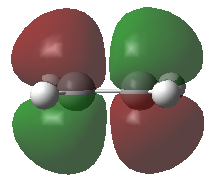

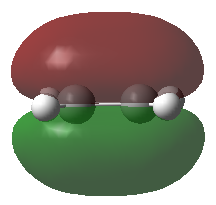

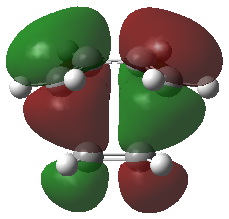

MO analysis and Orbital Symmetries

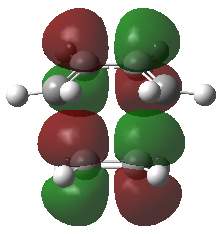

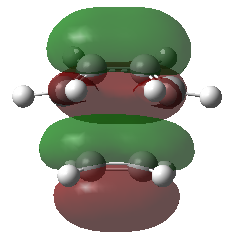

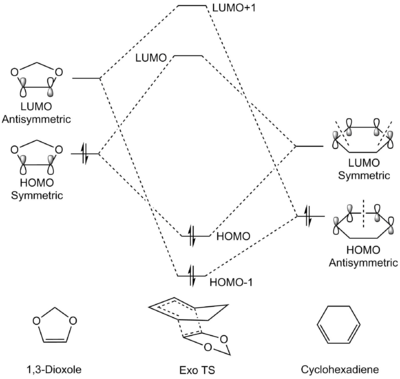

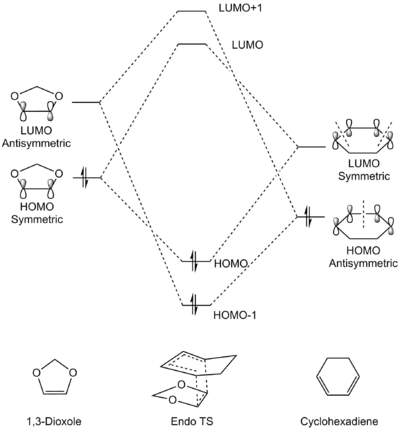

Frontier Molecular Orbitals (FMOs) of the reactants and transition state are visualised below. Table 2 screenshots of the FMOs from GaussView, and Fig. 4 traces the FMO overlaps with an MO diagram.

(Fv611 (talk) 17:18, 15 March 2017 (UTC) You switched around the HOMO and HOMO-1 in your diagram: the antisymmetric MO for the transition state has the lowest energy (as you correctly identified in the table below). You did the opposite for LUMO and LUMO+1: you correctly placed them in the MO diagram, but wrongly assigned them in the table: LUMO is the symmetric one, while LUMO +1 is antisymmetric.)

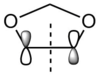

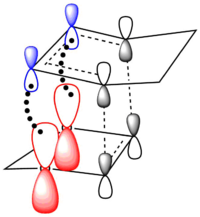

The reaction proceeds via a 6π electron electrocyclic reaction.

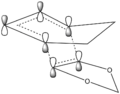

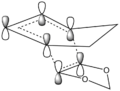

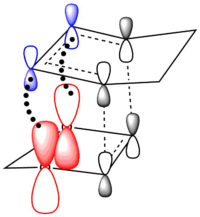

As seen on the MO diagram on the right (Fig. 2), reactions are only symmetry-allowed when the reactant orbital symmetries are identical. For example, the antisymmetric HOMO of butadiene reacts with the antisymmetric LUMO of ethylene even though the symmetric ethylene HOMO is much closer in energy. This can be explained by the orbital overlap integral. If symmetric and antisymmetric orbitals interact, the orbital overlap will be zero. Therefore, new molecular orbitals cannot be formed and the molecules do not react in that particular manner. Resultant MO bonding-antibonding pairs will carry the same symmetry label as their constituent MOs. This can be seen by how the pairs (HOMO-1,LUMO) and (HOMO, LUMO+1) retained the same symmetry labels as their constituent MOs in the table above. [11]

Bond Distances

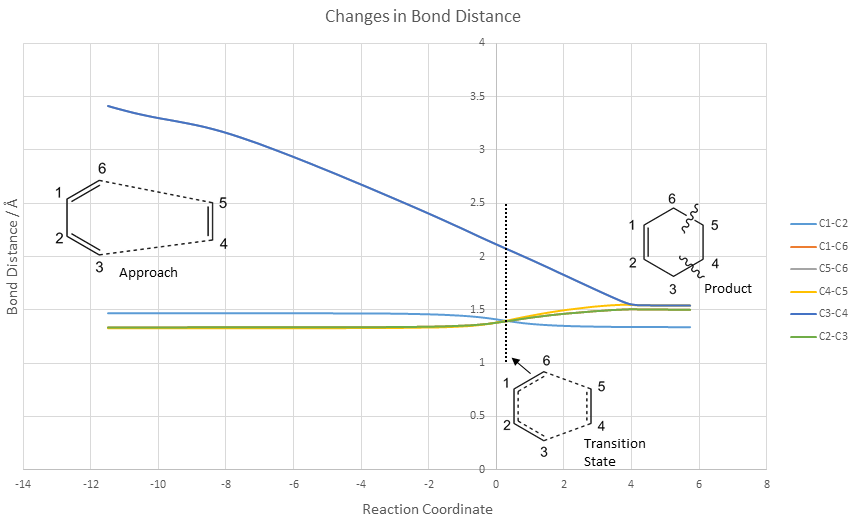

Changes in bond distances are documented below:

| Species | C1-C2 | C2-C3 | C3-C4 | C4-C5 | C5-C6 | C6-C1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Butadiene | 1.47079 | 1.33343 | - | - | - | 1.33342 |

| Ethylene | - | - | - | 1.32731 | - | - |

| Transition State | 1.41111 | 1.37973 | 2.11507 | 1.38174 | 2.11435 | 1.37978 |

| Product | 1.33700 | 1.50087 | 1.53711 | 1.53456 | 1.53709 | 1.50086 |

The van der Waals radius of carbon is 1.70 Å, and the typical length of a sp3-sp3 C-C bond is 1.53 Å and the typical length of a sp2-sp2 C=C bond is 1.34 Å.[12]

Distance between C4 and C5 increases in both the transition state and the final product due to the C=C double bond (sp2) in ethylene changing to a C-C single bond (sp3). Likewise, bond lengths between C1 and C6 and C2 and C3 lengthen as the C=C double bonds change to C-C single bonds. Bond lengths between C1 and C2 shorten as the C=C double bond is formed via a partial double bond in the transition state. The developing bonds between C3-C4 and C5-C6 in the transition state have the longest bond lengths in the table. However, bonding interactions are still present as these are still shorter than the twice the van der Waals radii of two carbon atoms (3.40 Å).

In the product, the C2-C3 and C6-C1 bond lengths are both slightly shorter than the typical sp3-sp3 C-C bond lengths. This suggests a small degree of additional hyperconjugation between neighbouring C-H σ bonds and the C=C π bond, resulting in a small contraction in the bonds.

The graph above characterises the C-C bond length variations throughout the reaction.

The approach of the dienophile is shown by steadily decreasing C3-C4 bond lengths and C5-C6 bond lengths (both graphs overlap exactly). At the reaction coordinate shown by the black dotted line, the transition state is reached. The transition state is characterised by identical C1-C6, C1-C2, C2-C3 and C4-C5 bond lengths due to delocalisation, and longer C3-C4 distances. Eventually, the C1-C2 bond length, C3-C4 and C5-C6 bond lengths contract to form a sp2 C=C bond and two sp3 C-C bond lengths respectively. C2-C3, C1-C6 and C4-C5 bonds lengthen to form three sp3 bonds.

Vibrations and Reaction Path

An Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC) calculation was performed on the obtained transition state. The vibration corresponding to the imaginary frequency in the transition state and the reaction path obtained from the IRC calculation are animated below:

| Vibration | Reaction Path |

|---|---|

948.8 i cm-1 |

|

The imaginary mode is a good reflection of the eventual path of the reaction.

This Diels-Alder reaction is synchronous, meaning that bond formation on each side of the reactant occurs simultaneously and at the same rate.

Exercise 2: Reaction between 1,3-dioxole and 1,3-cyclohexadiene

1,3-Dioxole can react with cyclohexadiene to form exo and endo adducts in two [4+2] Diels-Alder cycloaddition pathways. This reaction was simulated with the B3LYP/6-31G(d) basis set and the DFT method, following methodologies stated in the Methods and Basis Sets Used section. Unlike Exercise 1, this reaction contains two oxygen atoms on the dienophile (1,3-Dioxole), which may interfere with the orbital energies, producing better overlap as examined below.

MO Analysis

| Exo TS | Endo TS |

|---|---|

|

|

(Good MO diagrams, but are the energies arbitrary? It might be misinterpreted that the Endo LUMO and LUMO+1 are higher in energy Tam10 (talk) 16:09, 15 March 2017 (UTC))

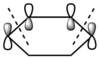

In a similar fashion as Exercise 1, only orbitals of identical symmetry combine to produce new orbitals in the transition state, as illustrated in both the table and the Chemdraw diagrams. Contrary to Exercise 1, the energy levels of the dienophile (1,3-dioxole) is shifted higher. This is due to the presence of two π-electron donating oxygen atoms adjacent to the alkene, causing the electron density of the alkene to increase and hence pushing the orbitals higher in energy. Therefore, the symmetric HOMO of the dienophile and symmetric LUMO of the diene are much closer in energy compared to Exercise 1, resulting in stronger mixing and a larger stabilisation energy. The stronger orbital interactions will result in a faster and more favourable reaction compared to Exercise 1, although direct comparison of energies are not possible here as the calculations were done in different basis sets. This also identifies the Diels-Alder reaction between 1,3-dioxole and cyclohexadiene as an inverse electron demand Diels-Alder reaction.[5][4]

Vibration and Reaction Path

| Pathway | Vibration | Reaction Path |

|---|---|---|

| Exo |  528.8 i cm-1 |

|

| Endo |  520.9 i cm-1 |

|

As in Exercise 1, the imaginary frequency present in the transition state closely follows the reaction trajectory.

In both reaction pathways, both molecules approach each other in planar configurations and the sp3 C-C single bond rotates to its higher-energy eclipsed conformer. The rotation will prevent steric interactions between hydrogen atoms on the cyclohexene ring and the approaching dioxole. Both carbons are then locked in the eclipsed conformation in the product due to the new bridge on the cyclohexene ring.

Reaction Path Energies (Thermochemistry)

Free energies of all products, reactants and transition states taken from the .log files of the calculations are presented below.

| Pathway | 1,3-Dioxole / Eh | Cyclohexadiene / Eh | TS / Eh | Product / Eh | Reaction Barrier / kJmol-1 | Reaction Energy / kJmol-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exo | -267.068642 | -233.324375 | -500.329165 | -500.373258 | 167.6 | -64.1 |

| Endo | -500.332153 | -500.418691 | 159.8 | -67.4 |

As the endo pathway has a lower reaction barrier and a lower reaction energy, it is both the kinetic and thermodynamic product. Therefore, it is likely to be produced in significant excess in a reaction under kinetic or thermodynamic conditions.

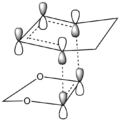

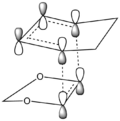

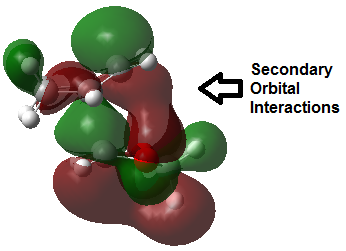

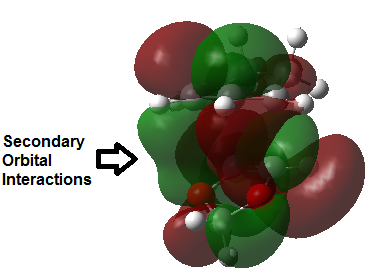

Secondary Orbital Interactions and Sterics

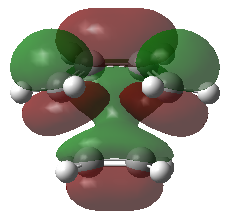

The Endo pathway has a smaller activation barrier as the transition state is more stable (of lower energy) compared to that of the Exo pathway. This is because the transition state is stabilised by secondary orbital interactions, which are illustrated in the table below:

| HOMO | ChemDraw of HOMO | LUMO+1 | ChemDraw of LUMO+1 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

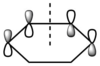

In the endo transition state structure, the p orbitals on oxygen in 1,3-dioxole are of the correct symmetry and are large enough to overlap with alkene p-orbitals in cyclohexadiene. This produces stabilising interactions in TS orbitals HOMO and LUMO+1, resulting in a lower energy transition state and hence a lower activation energy.

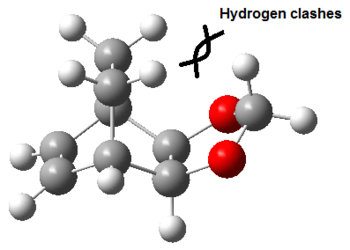

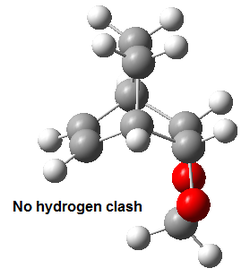

The Exo product has a higher energy compared the Endo product due to destabilising steric interactions, as shown below:

| Exo | Endo |

|---|---|

|

|

As shown in the table above, hydrogens in the carbon of the 1,3-dioxole ring will clash with hydrogens on the carbon bridge, resulting in destabilising interactions. This results in the exo structure being higher in energy than the endo structure, which does not suffer from such steric clashes.

Nf710 (talk) 17:41, 21 March 2017 (UTC) Your energies are correct. Well done, And you have drawn the SSO and steric clashes very nicely. It is extremely intuitive and easy to understand.

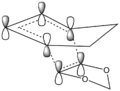

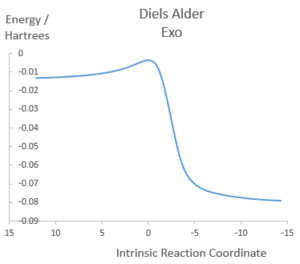

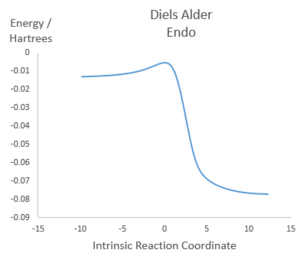

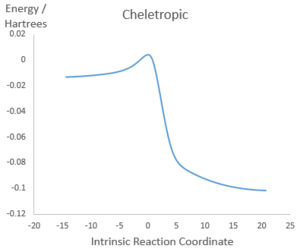

Exercise 3

Sulfur dioxide can react with 1,2-dimethylenebenzene via two diels-alder pathways (exo and endo) and a cheletropic pathway as shown above. This exercise investigates the energies of all three different pathways and visualises the reaction paths with Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate calculations. All calculations were performed with the semi-empirical PM6 method.

The MO diagrams of the FMOs are not shown here as similar orbitals react. However, it should be noted that this is an example of a normal electron demand Diels-Alder reaction, as SO2 is electron-poor and therefore the reaction features a large HOMOdiene-LUMOdienophile overlap.

Illustrations of IRCs

| Diels Alder Exo |

Diels Alder Endo |

Cheletropic |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Both Diels-Alder pathways feature asynchronous bond formation, as the C-O bond is formed before the C-S bond. All three reactions involve rapid aromatisation of the cyclohexene ring, which suggests that xylylene is unstable as any molecule that can form a bridge between the two double bonds outside the ring can trigger aromatisation into benzene, which is very energetically favourable. Therefore, there will be a driving force for the molecule to react quickly with incoming electrophile and nucleophiles, resulting in instability.

Pathway Energies

| Pathway | SO2 / Eh | Xylylene / Eh | TS / Eh | Product / Eh | Reaction Barrier / kJmol-1 | Reaction Energy / kJmol-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exo | -0.118614 | 0.178 | 0.092075 | 0.021451 | 85.8 | -99.6 |

| Endo | 0.090559 | 0.021698 | 81.8 | -98.9 | ||

| Cheletropic | 0.095059 | 0.000005 | 93.7 | -155.9 |

(Don't drop off significant figures in the energy calculations! Just 0.0005 Hartrees off leads to a 1 kJ/mol difference. It also looks like you've misread the Cheletropic TS energy and have a lower barrier than expected Tam10 (talk) 16:09, 15 March 2017 (UTC))

Under kinetic conditions, the endo product would be formed preferentially as it has the lowest energy transition state. Under thermodynamic/equilibrating conditions, however, the cheletropic product will be formed preferentially as it is the lowest energy product. This is consistent with experimental observations that the Diels-Alder adducts are kinetic products and cheletropic adducts are thermodynamic products[13].

Conclusion

Three Diels-Alder reaction (butadiene/ethylene in Exercise 1; 1,3-dioxole/cyclohexadiene in Exercise 2; SO2/1,2-dimethylenebenzene in Exercise 3) have been examined with the semi-empirical PM6 method and ab initio DFT method with the B3LYP/6-31G(d) basis set. An additional cheletropic pathway has been examined in Exercise 3. All reactants and products have been optimised to minima and all transition states have been optimised to first-order saddle points. All three reaction paths have been fully visualised with IRC calculations. Molecular orbitals in the transition state and reactants have also been visualised. Upon examination of the Frontier Molecular Orbitals (FMOs), the electron demand of the Diels-Alder reaction in Exercise 2 has been determined as an inverse electron demand Diels-Alder reaction. Energies of Exo and Endo pathways in Exercise 2 and Exercise 3 have been compared. In Exercise 2, the Endo pathway was deemed to be the most stable kinetically and thermodynamically. In Exercise 3, the endo product is deemed as the kinetic product while the cheletropic product is the most thermodynamically stable product despite it having the highest reaction barrier.

References

- ↑ Image taken from: http://sf.anu.edu.au/~vvv900/gaussian/ts/

- ↑ E. Lewars, Computational Chemistry, 2010, 9-43.

- ↑ A. James B. Foresman, Exploring Chemistry With Electronic Structure Methods, Gaussian, 1st edn., 1996.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 J. Clayden, N. Greeves and S. Warren, Organic chemistry, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1st edn., 2012.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 E. Eibler, P. Höcht, B. Prantl, H. Roßmaier, H. Schuhbauer, H. Wiest and J. Sauer, Liebigs Annalen, 1997, 1997, 2471-2484.

- ↑ J. Stewart, Journal of Molecular Modeling, 2007, 13, 1173-1213.

- ↑ A.D. Becke, J.Chem.Phys. 98 (1993) 5648-5652

- ↑ C. Lee, W. Yang, R.G. Parr, Phys. Rev. B 37 (1988) 785-789

- ↑ S.H. Vosko, L. Wilk, M. Nusair, Can. J. Phys. 58 (1980) 1200-1211

- ↑ P.J. Stephens, F.J. Devlin, C.F. Chabalowski, M.J. Frisch, J.Phys.Chem. 98 (1994) 11623-11627

- ↑ J. Ross, G. Whitesides and H. Metiu, Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English, 1979, 18, 377-392.

- ↑ D. R. Lide, Tetrahedron, 1962, 17, 125–134.

- ↑ D. Suarez, T. L. Sordo, J. A. Sordo, J. Org. Chem., 1995, 60 (9), 2848–2852

Log files of calculations

Exercise 1

File:SL8514 CYCLOHEXENE PM6.LOG

File:SL8514 CYCLOHEXENE TS PM6.LOG

File:SL8514 ETHYLENE PM6.LOG

File:SL8514 SCIS BUTADIENE PM6.LOG

File:SL8514 CYCLOHEXENE IRC PM6.LOG

File:SL8514 CYCLOHEXENE PRE TS MODRED PM6.LOG

Exercise 2

PM6

File:SL8514 13 DIOXOLE PM6.LOG

File:SL8514 CYCLOHEXADIENE PM6.LOG

File:SL8514 EX2 ENDO PDT PM6.LOG

File:SL8514 EX2 ENDO TS PM6.LOG

File:SL8514 EX2 EXO PDT PM6.LOG

File:SL8514 EX2 EXO TS PM6.LOG

B3LYP/6-31G(d)

File:SL8514 13 DIOXOLE B3LYP 631GD.LOG

File:SL8514 CYCLOHEXADIENE B3LYP 631GD.LOG

File:SL8514 EX2 ENDO IRC B3LYP 631GD.log

File:SL8514 EX2 ENDO PDT B3LYP 631GD.LOG

File:SL8514 EX2 EXO IRC B3LYP 631GD.log

File:SL8514 EX2 EXO B3LYP 631G REDO FREQ.LOG

Note that the starting structure of the calculation above of the Exo product was taken from the .log file of the IRC calculation and a frequency analysis was run, where no imaginary frequencies were found.

Exercise 3

File:SL8514 EX3 12DIMETHYLENEBENZENE PM6.LOG

File:SL8514 EX3 SO2 PM6.LOG

File:SL8514 EX3 CHELETROPIC IRC PM6.LOG

File:SL8514 EX3 CHELETROPIC PDT PM6.LOG

File:SL8514 EX3 CHELETROPIC PRE TS PM6.LOG

File:SL8514 EX3 CHELETROPIC TS PM6.LOG

File:SL8514 EX3 DA ENDO IRC PM6.LOG

File:SL8514 EX3 DA ENDO PDT PM6.LOG

File:SL8514 EX3 DA ENDO PRE TS PM6.LOG

File:SL8514 EX3 DA ENDO TS PM6.LOG

File:SL8514 EX3 DA EXO IRC PM6.LOG

File:SL8514 EX3 DA EXO PDT PM6.LOG

File:SL8514 EX3 DA EXO PRE TS PM6.LOG

File:SL8514 EX3 DA EXO TS PM6.LOG