Rep:Mod:SAMROWE003

3rd Year Computational Chemistry - Sam Rowe

Module 3 - Transition states and reactivity

The aim of Module 3 is to investigate how computational chemistry can be used to predict and model the transition state structures of larger molecules, further building on the computational techniques which were explored in Modules 1 and 2. For these types of calculations, it is no longer possible to use the same methods as were explored previously because they do no explicitly define the making/breaking of bonds or the variations of electronic distribution. Instead, a molecular orbital approach is employed to numerically solve the Schrödinger, create a potential energy surface and hence predict the transition state structure based on the local shape of this surface.

The transition state structures associated with the Cope Rearrangement and the Diels-Alder reaction are to be investigated as part of this module.

The Cope Rearrangement

Introduction

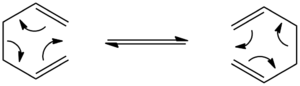

In the first part of the module, the Cope Rearrangement of 1,5-cyclohexadiene will be investigated. This rearrangement is an example of a pericyclic reaction. Pericyclic reaction can be defined in the following way[1]:

"All pericyclic reactions share the feature of having a cyclic transition structure, with a concerted movement of electrons simultaneously breaking bonds and making bonds. Within that category, it is convenient to divide pericyclic reactions into four main classes. These are cycloadditions, electrocyclic reactions, sigmatropic rearrangements and group transfer reactions..."

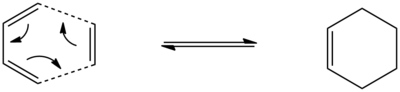

The reaction in question falls under the sigmatropic rearrangements category and is formally defined as a [3,3] sigmatropic rearrangement[2]. The mechanism of the reaction is given below:

This rearrangement is thought to proceed in a concerted fashion via either a chair or a boat transition state. The research carried out by O. Wiest et al.[3] determined that the chair transition state is approximately 5-6 kcal mol-1 lower in energy than the boat.

Calculations within this module will be used to determine the lowest energy conformation of the reactants via a simple energy optimisation followed by more sophisticated method. Frequency analysis can be used to support that an energy minimum has been found. The frequency analysis will also supply thermochemical details relating to each of the conformations.

The transition states can then be modelled directly by optimising their structures under a method which accounts for the more complex interactions related to a transition state. Again, frequency analysis will determine whether the transition state has indeed been found. Finally, an IRC (intrinsic reaction coordinate) analysis makes it possible to follow and analyse the lowest energy pathway from a transition state down to a local minimum on the potential energy surface.

Throughout the module, each of the initial molecules were drawn using GaussView 5.0. This program was also used as the interface to visualise all the results (i.e. spectra, vibrational modes, molecular orbitals, optimised structures etc.). Gaussian 09W was employed to carry out all of the calculations. Instead of running the calculations on the laptop, the input files were submitted to the SCAN server to save time. The LOG FILES produced by using the SCAN server have been included in the analysis.

Optimising the Reactants and Products

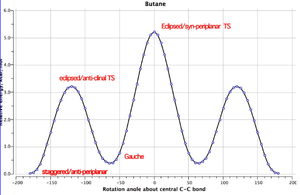

To start, the lowest energy conformations of 1,5-hexadiene were considered. It is important to analyse the structures which are lowest in energy because these are the structures which the molecule is most likely to display at a given temperature. The graph below[4] displays the relative energies of the different conformations of butane as the molecule rotates around the central C-C bond.

From this graph, it can be seen that the lowest energy conformations of butane are found when there is an antiperiplanar or a syn-clinal (gauche) relationship between the methyl groups (when looking along the central C-C bond). The dihedral angle between the methyl groups is 180° for the antiperiplanar arrangement and 60° for the gauche arrangement.

Further to this, it can also be assumed that the gauche and antiperiplanar conformations are also the lowest energy structures for 1,5-hexadiene with the antiperiplanar conformation being lower in energy. Four 'anti' conformations and six 'gauche' conformations were drawn on GaussView and their structures were corrected using the Edit-Clean option. Each of the structures were then submitted to the SCAN server to optimise their geometries. The Hartree Fock method was used with a basis set of 3-21G and the %mem was changed to 250MB. These calculations yielded an overall energy for each of the conformations as well as the point group (using the Edit-Symmetrize option). The results are given below and the 3D .mol images are available by clicking on the appropriate links:

| Name Of Conformation And 3D Molecule | Total Energy (Ha) And LOG FILE | Relative Energy (kcal mol-1) | Point Group |

|---|---|---|---|

| ANTI 1 | -231.69260[5] | 0.04 | C2 |

| ANTI 2 | -231.69254[6] | 0.08 | Ci |

| ANTI 3 | -231.68907[7] | 2.25 | C2h |

| ANTI 4 | -231.69097[8] | 1.06 | C1 |

| GAUCHE 1 | -231.68772[9] | 3.10 | C2 |

| GAUCHE 2 | -231.69167[10] | 0.62 | C2 |

| GAUCHE 3 | -231.69266[11] | 0.00 | C1 |

| GAUCHE 4 | -231.69153[12] | 0.71 | C2 |

| GAUCHE 5 | -231.66962[13] | 1.91 | C1 |

| GAUCHE 6 | -231.68916[14] | 2.20 | C1 |

The relative energies were calculated using the following conversion: 1 Ha = 627.5 kcal mol-1.

The analysis shows that the gauche 3 conformation is the lowest in energy, closely followed by the anti 1 and the anti 2 structures. This is quite unexpected because the graph suggests that an antiperiplanar arrangement should be the lowest in energy. Chemical knowledge would dictate that there is also a much better orbital overlap in the antiperiplanar arrangement because of the more favourable alignment. This notion is also supported by the calculations carried out for the 2nd Year Lecture Course[15] which states that the gauche conformation is approximately 3 kJ mol-1 higher in energy than the antiperiplanar conformation.

Due to this, the three conformations which were found to be lowest in energy were subsequently subjected to a geometry optimisation under the DFT-B3LYP method with a basis set of 6-31G*. This method is much more sophisticated and so will hopefully give a much more accurate approximation of the relative energies of the three structures. The results are shown in the table below and the optimised geometries under this method are available to view as a 3D image:

| Name Of Conformation And 3D Molecule | Total Energy (Ha) And LOG FILE | Relative Energy (kcal mol-1) | Point Group |

|---|---|---|---|

| ANTI 1 | -234.61180[16] | 0.00 | C2 |

| ANTI 2 | -234.61170[17] | 0.06 | Ci |

| GAUCHE 3 | -234.61133[18] | 0.29 | C1 |

It is evident that this method has altered the relative energies of the three conformations. From the further optimisation, the anti 1 conformation is predicted to be the lowest in energy followed by the anti 2 and then the gauche 3 conformation. This reflects the predictions made earlier. The DFT-B3LYP/6-31G* method has produced structures which are all approximately 3 Hartrees lower in energy than the HF/3-21G optimised structures.

Structurally, the two methods afforded very similar results in terms of bond angles and bond lengths. This is because the structures in question are relatively simple. Larger differences will usually be observed when carrying out an analysis on much larger molecules because each of the methods can account for very different parameters when optimising a geometry.

Frequency Analysis of the Reactants and Products

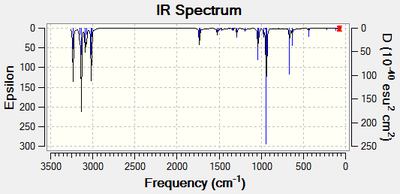

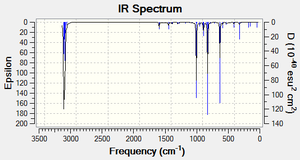

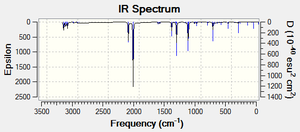

Next, a frequency analysis of the three lowest energy conformations was carried out to determine whether an energy minimum had been found. The predicted IR spectrum for the anti 1 conformer is shown below in full:

The other two spectra have been excluded because they display almost exactly the same peaks as each other. Overall, the three conformations all display the expected vibrational modes for a linear hydrocarbon. These include the C-H stretching, bending and rocking mode as well as modes associated with the C-C bond. The most important vibrational mode to consider is that associated with the alkene C=C moiety. The peak is expected to occur at around 1680 - 1620cm-1[19]. The C=C vibrational modes are tabulated below for both of the anti conformations. Each of these conformations display a symmetric and an asymmetric vibrational mode associated with the two alkene bonds with the asymmetric mode found at a higher wavenumber. The two types of vibrational modes have been supplied as animations below the table:

| Name Of Conformation And LOG FILE | Description Of Vibration Mode | Frequency Of Vibrational Mode

(cm-1) |

Intensity Of Vibrational Mode |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti 1[20] | Symmetric C=C stretch | 1731 | 5 |

| Anti 1 | Asymmetric C=C stretch | 1734 | 14 |

| Anti 2[21] | Symmetric C=C stretch | 1731 | 0 |

| Anti 2 | Asymmetric C=C stretch | 1734 | 18 |

Since no negative frequencies were obtained, it has been proven that the structures produced by geometry optimisation are in fact global minima in terms of energy. The peak values obtained aren't particularly close to those stated in the literature and have an associated error of approximately 3%. The predicted peaks were all found to be within 8% of the literature which is known to be the maximum error to take into consideration when dealing with this strategy of predicting IR peaks[22]

The gauche conformation displays two vibrational modes which are slightly different. This conformation still displays a symmetric and an asymmetric mode with the symmetric mode being found at a lower wavenumber. However, with this conformation, the degree to which the C=C bonds stretch is very different. In the symmetric stretch, the alkene bond on the 'right' (shown below) stretches at a much greater amplitude than the other bond. In the asymmetric stretch, the alkene bond on the 'left' stretches at a much greater amplitude than the other bond. This could be due to the very low symmetry of the gauche conformation (C1) The peak for each of the stretches still occurs at similar wavenumbers to those in the antiperiplanar conformations. The predicted data is given below. The two images highlight which bond stretches at the greater amplitude for each of the two vibrational modes:

| Name Of Conformation And LOG FILE | Description Of Vibration Mode | Frequency Of Vibrational Mode

(cm-1) |

Intensity Of Vibrational Mode |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gauche 3[23] | C=C vibrational mode 1 (SYMMETRIC) | 1732 | 7 |

| Gauche 3 | C=C vibrational mode 2 (ASYMMETRIC) | 1733 | 6 |

As in the previous two modules, frequency analysis has been shown to be a powerful tool in computational chemistry because the predictions are very accurate and the method rapidly determines whether a given structure has been optimised correctly. The next section describes how frequency analysis can also give even more detailed information about a given molecule.

Thermochemical Data for the Reactants and Products

By looking in the Gaussian output file, produced by running a frequency analysis, it was possible to find thermochemical data relating to each of the conformers. Four important values have been found and are included below for each of the three conformations.

i) The first value is the overall potential energy at 0K which includes the zero point vibrational energy (E = Eelec + ZPE)

ii) The second value is the overall potential energy at 298.15K and 1 atmosphere of pressure. This includes all of the contributions from vibrational, translational and rotational vibrational modes (E = E + Evib + Etrans + Erot)

iii) The third value is the correctional term for RT which is important to take into consideration when assessing a dissociation reaction (H = E + RT)

iv) The fourth value includes the entropic contributions to the free energy (G = H - TS)

Thermochemical Data (Ha) at 298.15K ANTI 1 Sum of electronic and zero-point Energies = -234.469286 Sum of electronic and thermal Energies = -234.461965 Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies = -234.461021 Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies = -234.500162

Thermochemical Data (Ha) at 298.15K ANTI 2 Sum of electronic and zero-point Energies = -234.469212 Sum of electronic and thermal Energies = -234.461856 Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies = -234.460912 Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies = -234.500821

Thermochemical Data (Ha) at 298.15K GAUCHE 3 Sum of electronic and zero-point Energies = -234.468693 Sum of electronic and thermal Energies = -234.461464 Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies = -234.460520 Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies = -234.500105

By modifying the Gaussian input file, it is actually possible to run the frequency analysis at a different temperature and pressure. The input files were changed appropriately to allow the calculations to be run at 0K and 1 atmosphere of pressure. To allow the calculation to run, a temperature of 0.0001K needed to be selected. With respect to this module, the selected value of 0.0001K is sufficient to allow a comparison with the values obtained at room temperature and pressure.

The data at 0K for each of the three conformations is shown below along with the LOG FILES produced:

Thermochemical Data (Ha) at 0.00K ANTI 1 Sum of electronic and zero-point Energies = -234.468848 Sum of electronic and thermal Energies = -234.468848 Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies = -234.468848 Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies = -234.468848

LOG FILE[24]

Thermochemical Data (Ha) at 0.00K ANTI 2 Sum of electronic and zero-point Energies = -234.468775 Sum of electronic and thermal Energies = -234.468775 Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies = -234.468775 Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies = -234.468775

LOG FILE[25]

Thermochemical Data (Ha) at 0.00K GAUCHE 3 Sum of electronic and zero-point Energies = -234.468256 Sum of electronic and thermal Energies = -234.468256 Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies = -234.468256 Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies = -234.468256

LOG FILE[26]

At 0K, it is possible to see that each of the four values are exactly the same. This is because there aren't any thermal contributions to the potential energy. At 0K, only the zero point energy is accounted for. At room temperature and pressure, it is possible to see that there are differences between each of the four values.

If additional time were available, it would have been interesting to carry out the calculations again at a variety of different temperatures and pressures to determine to what extent these parameters affect the total energy of a system.

As the temperature is increased, it is predicted that values ii) and iii) will increase. This is because as higher temperatures, there are greater thermal contributions to both the energy and enthalpy terms. It is predicted that value iv) will decrease as the temperature is raised. This can be rationalised by considering the equation for the Gibbs Free Energy above: G = H - TS. This shows that as the temperature is increased, the free energy will actually decrease because the '- TS' term becomes more negative.

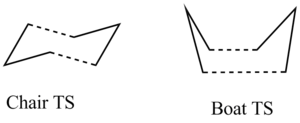

Optimising the Chair and Boat Transition Structures

The lowest energy reactants have been fully analysed and it is time to turn our attention to the two transition states. As mentioned in the introduction section, the reaction occurs via either a chair or a boat transitions state. The two transition states are shown in the figure below:

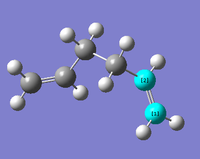

First, the chair transition state was modelled by initially drawing an allyl (CH2CHCH2) fragment on GaussView and optimising the geometry using the HF/3-21G method. Once optimised, two units of this allyl fragment were added to a single molecule window on GaussView. It was then possible to arrange the two units until they looked similar to the chair transition state. The distance between the two terminal ends of the allyl fragments was set to 2.20Å. The initial 'guess' at the chair transition state was then saved, ready for transition state optimisation.

Two methods were used to carry out this optimisation. During any transition state optimisation, the calculations needs to know where the negative direction of curvature is along the reaction coordinate.

i) The first method involves computing the force constant matrix at the first step of the optimisation and then updating it as the optimisation is carried out. This method is useful is the 'guess' at the transition state structure is reasonably accurate. However, this method can become problematic if the 'guess' at the transition state isn't close to the real structure. Fortunately, for this fairly simple and well defined transition state (the chair), this method can produce reliable results.

ii) The second method involves freezing the reaction coordinate and the optimising the rest of the molecule. Once this optimisation is complete, the reaction coordinate can be unfrozen and the transition state can then be determined. Doing this saves a lot of time because it is no longer necessary to compute the force constant matrix throughout the optimisation.

For the first method, the 'guess' structure was run under the Opt+Freq method using the HF/3-21G calculations. Unlike a general geometry optimisation, the option was selected to optimise to a TS (Berny). The force constant was to be calculated 'once' and 'opt=noeigen' was added to the Additional Words box. The latter addition ensured that the calculation didn't cease when an imaginary (negative) vibrational mode was reported. From this method, an imaginary frequency at -818cm-1 was found. The presence of this imaginary vibrational mode proves that a transition state structure has been found. The distance between the two terminal Carbons was found to be 2.02Å using this method. This vibrational mode has been animated and is shown below:

The second method was then carried out on the original 'guess' structure for the chair transition state. The frozen coordinate method comes in two parts. First, the 'guess' structure was opened in GaussView and the Redundant Coordinate Editor was opened. Using this, the distances between the two terminal Carbons were set at 2.20Å and the 'Freeze Coordinate' option was selected. A simple geometry optimisation of the structure was then run under the HF/3-21G method.

Once this had completed, the formatted checkpoint file was downloaded and opened in GaussView. The geometry of the transition state structure had been optimised but the distances between the two terminal Carbons remained at 2.20Å. It is now time to optimise the bond distances which were previously frozen. The Redundant Coordinate Editor was then used to change the description of the two bonds from 'Freeze Coordinate' to 'Derivative'. The Opt+Freq method (optimising to a TS (Berny)) was then carried out as in the first method. This optimisation produced exactly the same transition state structure as that produced from the first method. All of the structures can be viewed in the summary table at the end of this section. Both the imaginary vibrational frequency and the bond distance were exactly the same for both methods. This section has highlighted that both methods are able to produce reliable results. A greater difference between the time taken to perform each of the two methods would occur for larger or more complex molecules where the transition state is less well defined. For the boat transition state, a third method was employed: the QST2 method. For this method, both the reactants and the products of the reaction need to be specified prior to running any calculations. The method will then interpolate between the two methods and predict a transition states which lies between the two structures. The following reaction scheme shows the difference between the reactants and the products of this reaction (even though 1,5-hexadiene is the reactant AND product):

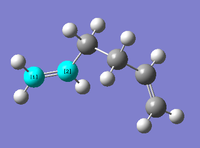

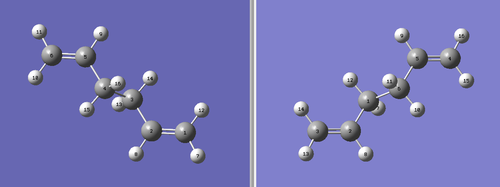

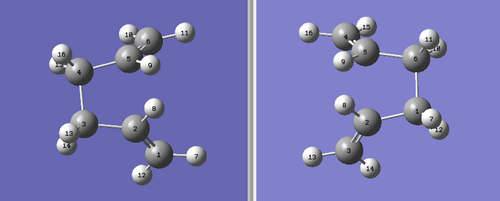

It is possible to manually label each of the Hydrogen and Carbons atoms using GaussView. To do this, two molecule windows were opened with each containing the fully optimised structure of the anti 2 conformer. The two molecules were placed side by side for facile comparison. The molecule on the left is the reactant molecule and the molecule on the right is the product. Each of the atoms were labelled in the following manner:

Next, an Opt+Freq calculation was run, optimising to a TS (QST2) for this particular method. However, the calculation failed after approximately 30 seconds on the laptop. This is because the calculation didn't consider that there could be rotation around the C-C bonds. This failure meant that the reactant and the product molecules needed to be altered further to allow the calculation to run properly. The dihedral angle for the central four Carbons (C2-C3-C4-C5) was set at 0° and the inside bond angles (C2-C3-C4 and C3-C4-C5) were set at 100°. This produced the following structures:

This time, the calculation worked and the transition state was modelled well. The presence of only one imaginary vibration (at -840cm-1) confirmed that the calculation was successful. For the boat transition state, the distance between the two terminal Carbon atoms was found to be 2.14Å. The imaginary vibration for the boat transition state is shown below. PLEASE NOTE: The animation may not be running automatically, so please click on the image and the animation should appear.

Finally, an overall summary of the geometry optimisation and the frequency analysis is shown below. 3D images of each of the optimised structures are available:

| Name Of Transition State | Frequency Of Vibrational Mode

(cm-1) |

|---|---|

| Chair | -818 |

| Boat | -840 |

| Name Of Transition State and 3D Image Of The Optimised Structure | Method Used And LOG FILE | Bond Length Between The Terminal Carbons (Å) |

|---|---|---|

| Original Allyl Fragment | HF/3-21G Optimisation[27] | --- |

| Chair | Optimisation To A TS (Berny)[28] | 2.02 |

| Chair | Frozen Coordinate Method[29] | 2.20 |

| Chair | Frozen Coordinate Method + [30] | 2.02 |

| Boat | Optimisation to a TS (QST2)[31] | 2.14 |

Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate Calculations for the Chair and Boat Transition Structures

It is almost impossible to predict which conformation the transition state structures will lead to simply by inspection. The Intrinsic Reaction coordinate method makes it possible to follow the minimum energy path from a transition state to a local minimum structure on the potential energy surface. The final structure can then be analysed further to determine the conformation which it is most similar to. Under the Gaussian calculation set-up, the IRC method was selected to be run over the chair transition state. For this initial calculation, only the forward direction of the reaction coordinate was computed because the reaction pathway is symmetrical. Additionally, the force constant was chosen to be calculated 'once' and the maximum number of steps was set at 50.

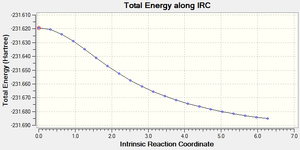

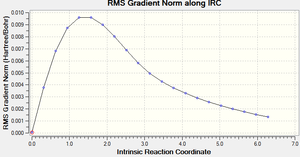

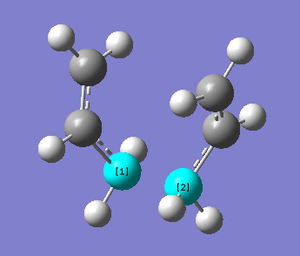

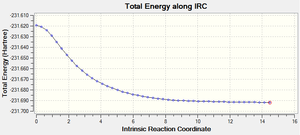

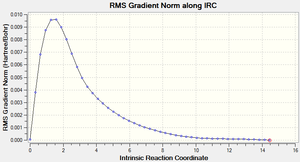

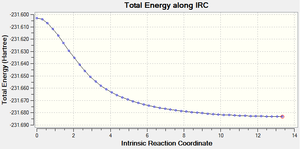

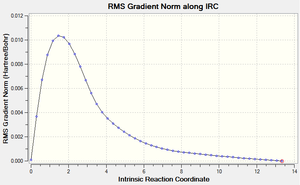

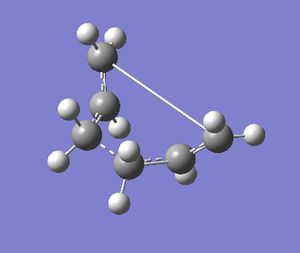

Below are the figures displaying the variation of the total energy and the RMS gradient at each step along the minimum energy pathway. An image of the final structure (after 21 steps) has also been provided:

The calculation terminated after 21 steps. The final structure doesn't exhibit an explicit bond between the two central Carbons, highlighted above. Because an overall energy minimum hasn't been reached, one of three paths can now be taken:

i) Take the final step structure of the IRC calculation and perform a normal energy minimisation. This is the fastest of the three methods but will be unsuccessful if the final structure isn't close enough to a local minimum.

ii) Carry out the IRC calculation again but increase the maximum number of steps. This method is fairly reliable, but if the maximum step limit is set too high, then the structure produced at the end can be very different to what would be expected.

iii) Carry out the IRC calculation again but specify that the force constant is computed 'always'. This method is by far the most reliable but the calculations can take a long to be completed, especially for larger molecular systems.

Method i) was carried out first. The structure produced after 21 steps of the initial method was subject to an optimisation under the HF/3-21G method. The symmetry (C2) and the total energy (-231.69167 Ha) are exactly the same as the values for the gauche 2 conformation which were calculated previously. This means that the gauche 2 structure is the most likely conformation to be formed after the transition state is reached. Method ii) was then carried out on the chair transition state. The maximum step limit was increased to 100 steps. As expected, this method produced exactly the same results as before. Because the calculation had terminated after 21 steps initially (with a maximum of 50), increasing the step limit did not make any difference and the calculation still terminated after 21 steps.

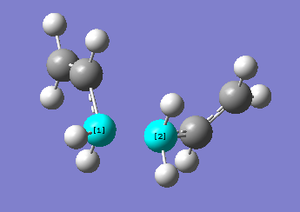

Method iii) produced much more interesting results. The graphs and the final structure (after 47 steps) are shown below:

With the force constant being calculated 'always', it is possible to see that an extra 26 steps were performed on the transition state to minimise the energy. The final structure produced did not have an explicit bond between the two highlighted carbons above. This time, the final structure required no further geometry optimisation because it was clear from the total energy (-231.69166 Ha) and from inspection that the structure resembled the gauche 2 conformation.

An IRC calculation was then carried out for the boat transition state. Calculating the force constant at every step gave much better results compared to calculating it once. Therefore, the boat transition state was run with the force constant calculated 'always' and the maximum number of steps was set to 50. This afforded the following two graphs and the final structure below:

The IRC calculations produced a very unusual final structure after 47 iterations. The following geometry optimisation didn't change the structure very much and the abnormally long bond was still present. This could be due to an error in the IRC or the geometry optimisation calculations. If time time was available, some different methods could have been explored to see whether more reliable results could have been obtained.

An overall summary of the methods has been tabulated below:

| Name Of Transition State And LOG FILE | Maximum Number Of Steps | Compute Force Constant? | Terminated After | Total Energy | RMS Gradient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chair[32] | 50 | Once | 21 Steps | -231.61932 | 0.00005537 |

| Chair[33] | 100 | Once | 21 Steps | -231.68514 | 0.00133708 |

| Chair[34] | 50 | Always | 47 Steps | -231.69166 | 0.00001157 |

| Boat[35] | 50 | Always | 47 Steps | -231.60280 | 0.00000577 |

Activation Energies for the Chair and Boat Transition Structures

For the final part of this section, both the boat and the chair transition state structures were subjected to a further geometry optimisation using the more sophisticated DFT-B3LYP/6-31* method. This allows for a comparison of the different methods which can be employed for optimising a molecular geometry.

The activation energy of the reaction has been calculated for each of the transition states under both methods. The activation energy of the reaction is the amount of energy required for the reactants to reach the transition states (which is the highest energy point on the reaction coordinate). For the HF/3-21G method, a comparison was made between the transition states and the gauche 3 conformation. The gauche 3 conformation was chosen because it was discovered that this conformation is the one lowest in energy, according to this basic method. For the DFT-B3LYP/6-31*, a comparison was made between the transition states and the anti 1 conformation. The anti 1 conformation was chosen because it was discovered that this conformation is the one lowest in energy, according to this much more advanced method. The energy difference was acquired via subtraction of the two values in Hartrees. This number was then converted to kcal mol-1 by multiplying by 627.5.

In addition to this, the activation energy was also calculated at 0.00K. To do this, the difference was taken between the electronic and zero point energy value and the electronic and thermal energy value. This energy is the additional energy required to activate the reaction at 0.00K. Therefore, the activation energy at 0.00K was found by adding this difference to the activation energy at 298.15K. The results are shown below. The point group of the transition states were found using the Edit-Symmetrize option on GaussView:

| Name Of Transition State | Symmetry | HF/3-21G Method - Electronic And Zero Point Energy | HF/3-21G Method - Electronic And Thermal Energy | Activation Energy (kcal mol-1) at 298.15K | Activation Energy (kcal mol-1) at 0.00K | DFT-B3LYP/6-31* Method - Electronic And Zero Point Energy And LOG FILE | DFT-B3LYP/6-31* Method - Electronic And Thermal Energy | Activation Energy (kcal mol-1) at 298.15K | Activation Energy (kcal mol-1) at 0.00K | Literature Activation Energy[36] (kcal mol-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chair | C2h | -231.466696 | -231.461337 | 46.02 | 49.36 | -234.411640[37] | -234.405180 | 35.97 | 40.02 | 33.5 ± 0.5 |

| Boat | C2v | -231.450926 | -231.445294 | 56.39 | 59.92 | -234.398505[38] | -234.392573 | 44.77 | 48.42 | 44.7 ± 2.0 |

For both of the transition states, it is clear that the more advanced DFT-B3LYP/6-31* method has provided much more accurate results which are much closer to the literature values provided in the table above. This is therefore the more suitable method when carrying out activation energy analysis because much better results are obtained and the time taken for the calculation to be carried out isn't particularly longer than the time taken for the basic method.

Conclusion 1

A range of new computational chemistry techniques have been used as part of this module so far. In terms of geometry optimisation, the DFT-B3LYP/6-31* method has been found to be much more reliable than the more primitive HF/3-21G method. The sophisticated method has provided optimised geometries which agree with the literature and theory. It has also been shown that this method is able to calculate thermochemical data to a much higher degree of accuracy. This is shown above in the activation energy calculations.

The transition states have been modelled very effectively using the Opt+Freq job type. The imaginary vibrations support the formation of the two transition states. The frozen coordinate method was found to be the fastest method for optimising the chair transition state. Even though this method came in two stages, the running of the calculations were very rapid. This method allowed the user to define the expected transition state much more explicitly than the force constant matrix method. The QST2 method worked well for the boat transition state but was rather more time consuming because the reactants and products needed to be manually defined. This process would probably not be the method of choice when dealing with ever larger molecular systems.

IRC calculations were shown to be an effective way of monitoring how a transition state relaxes to a local energy minimum. The method was further improved by having the force constant calculated 'always' although this did mean that the calculations took much longer to complete.

All of the techniques which have been used so far will be utilised in the second part of this module with regards to the Diels-Alder transition state.

The Diels-Alder Cycloaddition

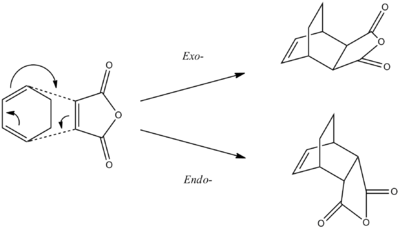

In this part of the module, the techniques which have been applied previously are to be used to model and analyse the transition states associated with two Diels-Alder reactions. The first reaction to be analysed is a relatively simple reaction between an ethene unit and a cis-butadiene unit. The endo- and exo- selectivity (which is usually associated with Diels-Alder reactions[39]) can then be investigated by modelling the transition states associated with the Diels-Alder reaction between cyclohexadiene and maleic anhydride. For this part of the module, a semi-empirical method will be used to optimise geometries and to model the transition states (the AM1 method). Additionally, molecular orbital analysis will be used to visualise the HOMO and the LUMO of the reactants and the transition state structures.

Introduction

A Diels-Alder reaction is a specific type of pericyclic reaction which falls under the cycloaddition category. For the reaction to be classed as a Diels-Alder, it must be a [4s + 2s] cycloaddition. In the reaction, the π orbitals of a diene (relatively more electron rich) form two new σ bonds with the π orbitals of a dieneophile (relatively more electron poor) in a concerted fashion. The reaction scheme for the first Diels-Alder reaction is shown below:

Optimising the Reactants of the Ethene/Butadiene Cycloaddition

First, both of the reactants were drawn using GaussView and they were subjected to an initial energy optimisation under the semi empirical AM1 method. This yielded the following results. The optimised structures can be viewed in 3D by using the relevant links:

| Name Of Reactant, 3D Image And LOG FILE | Total Energy | RMS Gradient |

|---|---|---|

| Ethene[40] | 0.02619 | 0.00003328 |

| Cis-Butadiene[41] | 0.04880 | 0.00001429 |

The low RMS gradients suggest that a minimum energy configuration has been found because the gradient of the potential energy curve has fallen very close to zero. The AM1 method is a more sophisticated method than the Hartree Fock method used previously. However, it isn't as accurate as the DFT-B3LYP/6-31* . The difference between the DFT-B3LYP/6-31* and the AM1 method will be highlighted as part of this module.

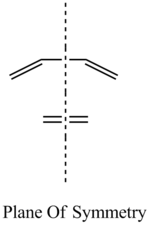

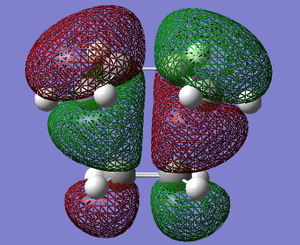

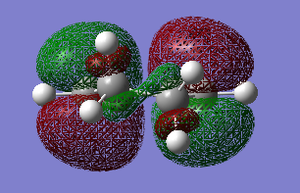

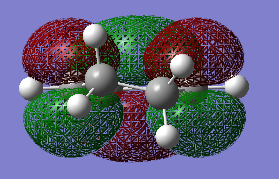

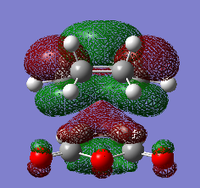

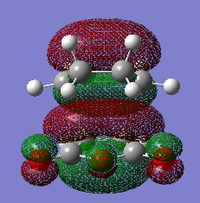

On GaussView, the HOMO and the LUMO of both the reactants were visualised. The surface was changed from 'solid' to 'mesh' because this makes it easier to view the entirety of the molecular orbitals. It is important to analyse the HOMO and the LUMO because these are the orbitals which interact during the reaction. The reaction can only proceed if the orbitals have the same symmetry with respect to the plane, shown below:

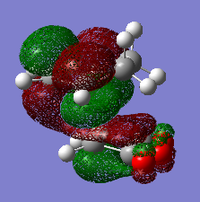

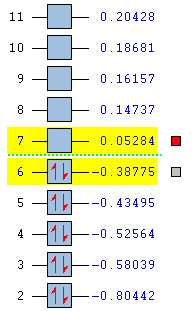

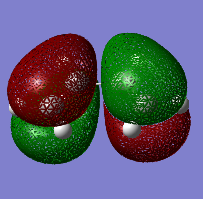

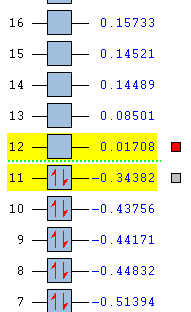

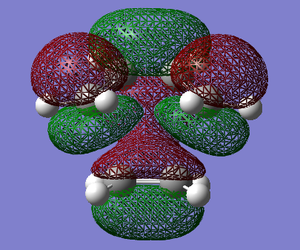

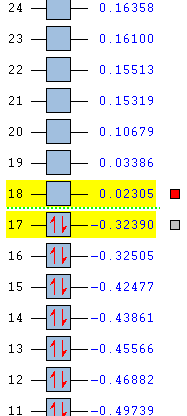

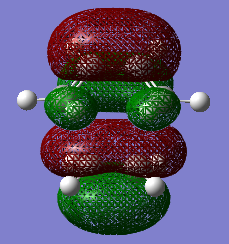

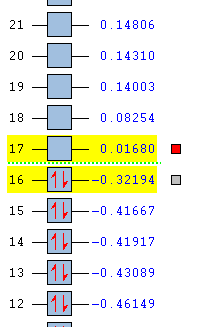

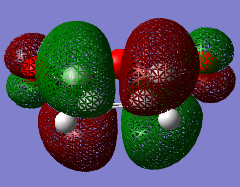

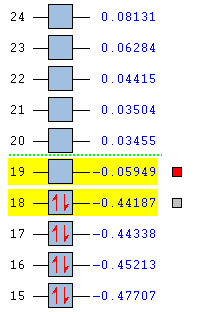

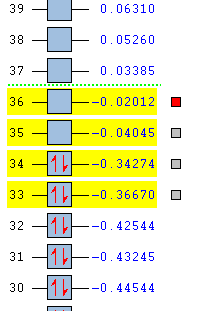

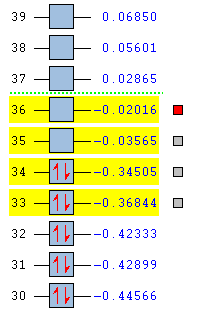

The HOMO and the LUMO for both cis-butadiene and ethene are provided below. Additionally, the overall molecular orbital energy summary has been included. This summary displays the relative energies (in Hartrees) and also the electronic occupancy of each energy level:

It can be seen that the HOMO of ethene is SYMMETRIC with respect to the plane and the LUMO is ANTI-SYMMETRIC with respect to the plane.

It can be seen that the HOMO of cis-butadiene is ANTI-SYMMETRIC with respect to the plane and the LUMO is SYMMETRIC with respect to the plane. In both cases, the HOMO is a bonding orbital and the LUMO is an anti-bonding orbital.

The HOMO of ethene and the LUMO of cis-buradiene both have the same symmetry (ANTI-SYMMETRIC) with respect to the plane. This makes it possible for the reaction to take place because there will be a favourable interaction between the HOMO and the LUMO.

Optimising the Transition State of the Ethene/Butadiene Cycloaddition

The optimised molecules of the reactants (ethene and cis-butadiene) were placed together on the same molecular window in GaussView. The two molecules were manipulated until they resembled the expected transition state structure. The ethene unit was placed directly above the cis-butadiene unit (as seen below).

To model the transition state, the frozen coordinate method was chosen because it is known to afford reliable results and the calculations do not require a large amount of computing power. First, the distance between the terminal Carbons was set to 2.00Å and the geometry was optimised under the AM1 method. Once this had completed, the two forming bonds were unfrozen and the 'derivative' option was chosen to allow the transition state to be optimised. In addition to this, the DFT-B3LYP/6-31G* method was also used to allow for a comparison between the two methods. The predicted IR spectrum (under the AM1 method) for the transition state is given below along with the imaginary vibrations associated with the formation of the two new σ bonds in the transition state:

It can be seen that there aren't many distinct differences between the transition states optimised under the two different methods.

For the DFT-B3LYP/6-31G* method, the lowest positive vibration has also been animated:

The two tables below provide an overall summary of the frequency analysis which was carried out under the two different methods:

| 3D Molecule And LOG FILE | Total Energy (Ha) | RMS Gradient | Description Of Vibrational Mode | Frequency Of Vibrational Mode

(cm-1) |

Intensity Of Vibrational Mode |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transition State[42] | 0.11165 | 0.00013219 | Imaginary Vibrational Mode | -952 | 6 |

| 3D Image and LOG FILE | Total Energy (Ha) | RMS Gradient | Description Of Vibrational Mode | Frequency Of Vibrational Mode

(cm-1) |

Intensity Of Vibrational Mode |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transition State[43] | -234.54390 | 0.00013219 | Imaginary Vibrational Mode | -952 | 6 |

| --- | --- | --- | Lowest Positive Vibrational Mode | 136 | 1 |

It is possible to see that the two methods have yielded the same frequency for the imaginary vibration (-952cm-1). The presence of the vibrational mode proves that the transition state structure has indeed been found. In both of the imaginary vibrations, it is possible to see that there is a concerted movement of the two sets of terminal Carbons forming the two new σ bonds. This correlates with the theory that a pericyclic reaction has a concerted movement of electrons. The lowest positive vibrational mode in the transition state shows the ethene unit rotating around a fixed axis, directly above the cis-butadiene unit. This motion suggests a non-concerted movement of electrons because of the lengthening and shortening of the two new σ bonds in an asymmetric fashion with respect to each other. If this type of motion was present in the transition state, it would contradict the governing theory behind pericyclic reactions.

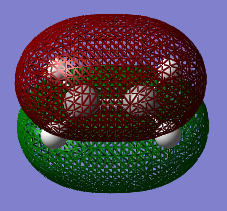

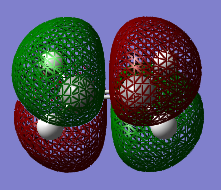

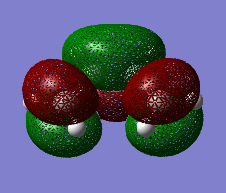

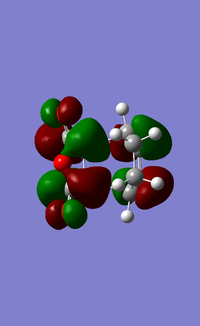

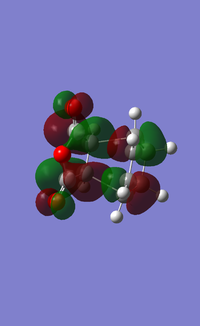

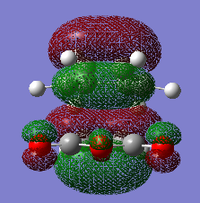

The HOMO and the LUMO of the transition state structures were visualised using GaussView. They are provided below:

The HOMO of the transition state under the AM1 method is ANTI-SYMMETRIC with respect to the plane and the LUMO is SYMMETRIC with respect to the plane.

The HOMO of the transition state under the DFT-B3LYP/6-31G* method is SYMMETRIC with respect to the plane and the LUMO is SYMMETRIC with respect to the plane.

In this case, the two methods have ordered the energy levels slightly differently. The AM1 method has predicted that the HOMO is a bonding orbital and the LUMO is an anti-bonding orbital. However, the DFT-B3LYP/6-31G* method has predicted that both the HOMO and the LUMO are bonding orbitals. The molecular orbitals in the transition state can be directly compared to the molecular orbitals which were modelled previously for the reactants. This analysis can be used to determine the contributions from each of the two reactant orbitals to the transition state orbitals.

Transition State HOMO (AM1) = ethene (LUMO) + cis-butadiene (HOMO)

Transition State LUMO (AM1) = ethene (HOMO) + cis-butadiene (LUMO)

The molecular orbital contributions from the DFT-B3LYP/6-31G* method cannot be directly compared because this method was not used previously to predict the molecular orbitals of the two reactants.

Using the query option on GaussView, the important bond lengths within the transition state have been measured. These are tabulated below:

| Point Group | Forming C-C Distance (Å) | Diene C=C Bond Length (Å) | Diene C-C Bond Length (Å) | Ethene C=C Bond Length (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cs | 2.12 | 1.38 | 1.40 | 1.38 |

| Point Group | Forming C-C Distance (Å) | Diene C=C Bond Length (Å) | Diene C-C Bond Length (Å) | Ethene C=C Bond Length (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cs | 2.27 | 1.38 | 1.41 | 1.39 |

A comparison of the two methods shows that the main difference is between the predicted length of the forming C-C bond distance. The bond lengths for the C-C and the C=C bonds are very similar for both the methods. From the literature[44], the C-C bond length is 1.53Å and the C=C bond length is 1.33Å. The predicted bond lengths from both of the methods are similar but not exactly the same. The C-C single bond is slightly shorter than the literature and the C=C double bond is slightly longer than the literature. These difference display that even the more sophisticated optimisation methods (DFT-B3LYP/6-31G*) are not always completely accurate. Additionally, the C=C double bonds maybe be slightly longer than expected because of the conjugated system present within the cis-butadiene molecule. This conjugation will weaken the C=C double bonds because the electron density is distributed over the molecule rather than being localised at a particular point between the two Carbons.

The van der Waals radius for Carbon is 1.70Å[45]. Therefore, for a non-bonded arrangement between two Carbons, the expected distance would be approximately: 2 x 1.70Å = 3.40Å. The C-C bonds which are forming in the transition state can be seen to be roughly half way between the non-bonded distance and the C-C single bond distance. This suggests that there is a predicted interaction between the two pairs of terminal Carbons which will eventually form the new σ bonds.

Optimising the Reactants of the Cyclohexadiene/Maleic Anhydride Cycloaddition

Another interesting Diels-Alder reaction to analyse is the reaction between maleic anhydride and cyclohexadiene. In this reaction, it is possible to explore the endo- and exo- selectivity which is often associated with reactions of this type. Under kinetic reaction conditions, the endo- product would predominate. However, under thermodynamic/equilibrating conditions, it will be the exo- product which predominates. The reaction scheme below shows the difference between the endo- and the exo- products of the reaction:

Both of the transition states can be modelled using the techniques which were used for the simple Diels-Alder reaction. First, the geometry of the two reactants was optimised using the semi-empirical AM1 method. The 3D images are available below along with the total energy and point group:

| Name Of Reactant, 3D Image And LOG FILE | Total Energy | RMS Gradient | Point Group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclohexadiene[46] | 0.02771 | 0.00000562 | C2 |

| Maleic Anhydride[47] | -0.12182 | 0.00003683 | C2v |

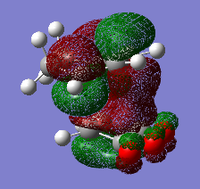

The low RMS gradients suggest that a minimum energy configuration has been found. The HOMO and the LUMO of both the reactants were also modelled using the AM1 method. These are provided below along with the molecular orbital energy summary (in Hartrees):

The HOMO of cyclohexadiene is ANTI-SYMMETRIC with respect to the plane and the LUMO is SYMMETRIC with respect to the plane.

The HOMO of maleic anhydride is SYMMETRIC with respect to the plane and the LUMO is ANTI-SYMMETRIC with respect to the plane.

In cyclohexadiene, the HOMO is a bonding orbital and the LUMO is an anti-bonding orbital. In maleic anhydride, both the HOMO and the LUMO are bonding orbtials.

Optimising the Transition States of the Cyclohexadiene/Maleic Anhydride Cycloaddition

The frozen coordinate method was successful for the ethene/cis-butadiene reaction so this is the method which has been employed for the maleic anhydride/cyclohexadiene reaction. The distance between the terminal Carbons was set at 2.10Å and the rest of the transition state was optimised. Once this had completed, the bond was given the 'derivative' option and the transition state was optimised again. This method was repeated for both the endo- and the exo- transition state. The predicted IR spectrum is shown below along with the imaginary vibrational modes associated with the forming of the new σ bonds:

The lowest positive frequency for the exo- transition state has also bee included below:

The imaginary vibrational modes display the concerted formation of the two new bonds which conforms to the theory behind pericyclic reactions. As with the ethene/cis-butadiene reaction, the lowest positive frequency displays a non-concerted motion associated with the forming C-C bonds.

An overall summary of the frequency analysis of both transition states is tabulated below:

| 3D Image and LOG FILE | Total Energy (Ha) | RMS Gradient | Description Of Vibrational Mode | Frequency Of Vibrational Mode

(cm-1) |

Intensity Of Vibrational Mode |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exo- Transition State[48] | -0.05042 | 0.00001135 | Imaginary Vibrational Mode | -812 | 97 |

| --- | --- | --- | Lowest Positive Vibrational Mode | 61 | 1 |

| Endo- Transition State[49] | -0.05150 | 0.00005454 | Imaginary Vibrational Mode | -807 | 71 |

| --- | --- | --- | Lowest Positive Vibrational Mode | 63 | 2 |

The AM1 method places the endo- transition state at a lower total energy than the exo- transition state. The DFT-B3LYP/6-31G* method is known to be a more sophisticated method than the semi-empirical AM1 method, so an additional optimisation was run to see how the relative energies and the geometries of the transition state changed. The 3D images of the transition states under the DFT-B3LYP/6-31G* method are provided below:

| Name Of Reactant, 3D Image And LOG FILE | Total Energy | RMS Gradient | Point Group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exo- Transition State[50] | -612.75579 | 0.00002758 | Cs |

| Endo- Transition State[51] | -612.75829 | 0.00002256 | Cs |

In both cases, the transition state structures which were optimised under the DFT-B3LYP/6-31G* are quite different from those optimised under the AM1 method. The differences in the structures arise because each of the methods deal with different molecular parameters when optimising a given geometry. In the DFT-B3LYP/6-31G* optimised transition states, both of the reactant molecules have been positioned in such a way as to reduce steric interactions. This has been achieved by 'bending' the structures to position them away from the Carbons atoms which are involved in the formation of the new bonds.

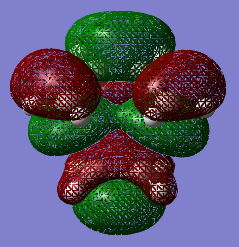

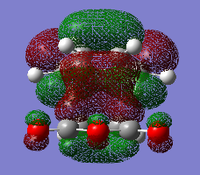

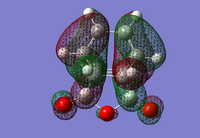

The molecular orbitals have been visualised using the AM1 method:

| Name Of Molecular Orbital | Exo- Transition State | Endo- Transition State |

|---|---|---|

| LUMO + 1 |  |

|

| LUMO |  |

|

| HOMO |  |

|

| HOMO - 1 |  |

|

For the exo- transition state, the LUMO + 1 is SYMMETRIC with respect to the plane, the LUMO is ANTI-SYMMETRIC with respect to the plane, the HOMO is ANTI-SYMMETRIC with respect to the plane and the HOMO - 1 is SYMMETRIC with respect to the plane.

For the endo- transition state, the LUMO + 1 is SYMMETRIC with respect to the plane, the LUMO is ANTI-SYMMETRIC with respect to the plane, the HOMO is ANTI-SYMMETRIC with respect to the plane and the HOMO - 1 is SYMMETRIC with respect to the plane.

As before, it is possible to determine the molecular orbitals of the reactants which make up the molecular orbitals in the transition state. Since only the HOMO and the LUMO were modelled previously, these are the only two orbitals which can be used in this analysis. It is very likely that the LUMO + 1 and the HOMO - 1 energy levels are actually made up of some extra orbital contribution than stated below. If more time were available, it would have been interesting to visualise the deeper orbitals associated with the reactant molecules. This would have given a better understanding into how the molecular orbitals in the transition state are made.

EXO- (LUMO + 1) = Maleic Anhydride (HOMO) + Cyclohexadiene (LUMO)

EXO- (LUMO) = Maleic Anhydride (LUMO) + Cyclohexadiene (HOMO)

EXO- (HOMO) = Maleic Anhydride (LUMO) + Cyclohexadiene (HOMO)

EXO- (HOMO - 1) = Maleic Anhydride (HOMO) + Cyclohexadiene (LUMO)

ENDO- (LUMO + 1) = Maleic Anhydride (HOMO) + Cyclohexadiene (LUMO)

ENDO- (LUMO) = Maleic Anhydride (LUMO) + Cyclohexadiene (HOMO)

ENDO- (HOMO) = Maleic Anhydride (LUMO) + Cyclohexadiene (HOMO)

ENDO- (HOMO - 1) = Maleic Anhydride (HOMO) + Cyclohexadiene (LUMO)

Each orbital in the transition state displays a combination of a HOMO and a LUMO from the reactant molecules.

For both the different transition states, the HOMO and the HOMO - 1 energy levels are occupied, bonding orbitals whereas the LUMO and the LUMO + 1 are unoccupied, bonding orbitals.

The LUMO + 1 molecular orbitals are shown below from the side to allow the secondary orbital interactions to be seen.

In these secondary orbital interactions, it can be seen that the carbonyl groups on the maleic anhydride unit interact with the cyclohexadiene orbitals. It is proposed that these secondary orbital interactions help to account for the regioselectivity of this particular reaction[52]. A much better overlap is seen between these orbitals in the endo- transition state, hence making this the more preferable product from the reaction.

GaussView was used to measure the bond lengths in both of the transition states. These are tabulated below:

| Transition State | Forming C-C Distance (Å) | Cyclo-Diene C=C Bond Length (Å) | Cyclo-Diene C-C Bond Length (Å) | Anhydride C=C Bond Length (Å) | Anhydride C=O Bond Length (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exo- | 2.17 | 1.39 | 1.40 | 1.40 | 1.22 |

| Endo- | 2.16 | 1.39 | 1.40 | 1.41 | 1.22 |

| Transition State | Forming C-C Distance (Å) | Cyclo-Diene C=C Bond Length (Å) | Cyclo-Diene C-C Bond Length (Å) | Anhydride C=C Bond Length (Å) | Anhydride C=O Bond Length (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exo- | 1.56 | 1.51 | 1.34 | 1.54 | 1.20 |

| Endo- | 1.56 | 1.51 | 1.34 | 1.54 | 1.20 |

In the case of this reaction, the two methods have predicted fairly different results for each of the bond lengths in the transition states. The DFT-B3LYP/6-31G* method has predicted that the forming C-C bond has a much smaller interatomic distance than that predicted by the AM1 method. The difference between the other bond lengths arises because the two methods produced very different transition state structures.

Conclusion 2

Overall, this module has shown that it is possible to accurately predict transition state structures using a variety of methods to create and analyse them. The AM1 method has been a powerful tool to use because it is able to rapidly and accurately predict molecular orbitals as well as imaginary frequencies and optimised geometries. The DFT-B3LYP/6-31G* method is a more sophisticated method but requires a lot more computing power which may not always be available, especially when analysing larger molecular systems.

Computational chemistry has made it possible to analyse the entirety of a chemical reaction, all the way from reactants, through the transition state to product. This is an important consideration to take before starting any chemical reaction experimentally because computations calculations will immediately give an indication of stereochemical outcomes and favourable reaction pathways.

It has been proven that imaginary frequencies (relating to the formation of new bonds) can be found and support the notion that pericyclic reactions occur in a concerted manner.

References

- ↑ I. Fleming, Pericyclic Reactions, Oxford University Press, 1999, pp 1

- ↑ H.Rzepa, 2nd Year Organic Lecture Course - Pericyclic Reactions, 2011, Lecture 5

- ↑ O. Wiest et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc., 116, 1994, pp 10336

- ↑ H.Rzepa, 2nd Year Organic Lecture Course - Conformational Analysis, 2011, Lecture 2

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11032

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11033

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11034

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11035

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11037

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11036

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11040

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11039

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11038

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11041

- ↑ H.Rzepa, 2nd Year Organic Lecture Course - Conformational Analysis, 2011, Lecture 2

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11042

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11043

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11044

- ↑ J. Coates, Encyclopaedia of Analytical Chemistry, R. A. Meyers (Ed.), 2000, pp 10815 - 10831

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11049

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11050

- ↑ 3rd Year Computational Chemistry Online Lab Manual, Module 1, 2011

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11051

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11185

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11186

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11187

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11162

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11163

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11164

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11165

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11166

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11167

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11168

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11169

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11170

- ↑ 3rd Year Computational Chemistry Online Lab Manual, Module 3, 2011

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11171

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11172

- ↑ J. Clayden et al., Organic Chemistry, Oxford University Press, United States, 2001, pp 905 - 918

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11217

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11216

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11219

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11218

- ↑ D. R. Lide, Tetrahedron, 17, 1962, pp 125 - 134

- ↑ A. Bondi et al., J. Phys. Chem., 68 (3), 1964, pp 441 - 451

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11226

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11227

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11290

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11291

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11293

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-11294

- ↑ I. Fleming, Frontier Orbitals and Organic Chemical Reactions, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2002, pp 106 - 108