Rep:Mod:RM3FNJ8

Module 3

The Cope Rearrangement

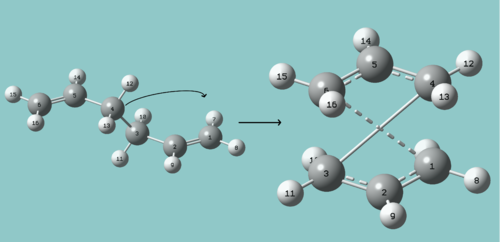

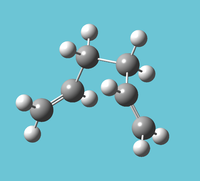

The rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene will be studied. In order to study the transition state in this reaction, the lowest energy conformation, and hence the most populated state of 1,5-hexadiene, must be found.

Predicting the Lowest Energy Conformer

| Conformation | Model | Point group | Energy (a.u.) | DOI | Structure in Table |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti |  |

Ci | -231.69253(521) | DOI:10042/to-13354 | anti2 |

| Gauche |  |

C2 | -231.69166(702) | DOI:10042/to-13355 | gauche2 but other "enantiomer" than that given |

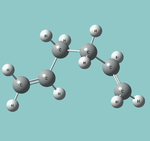

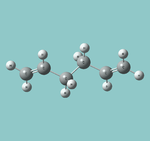

The first logical conformation to investigate is the completely linear form. The next logical step is to make a change symmetrical change in the molecule by modelling a gauche linkage in the center.

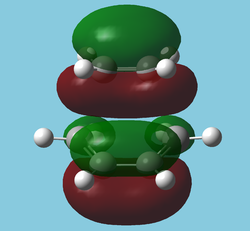

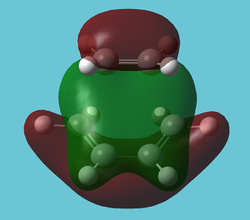

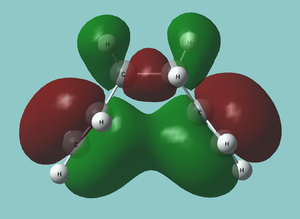

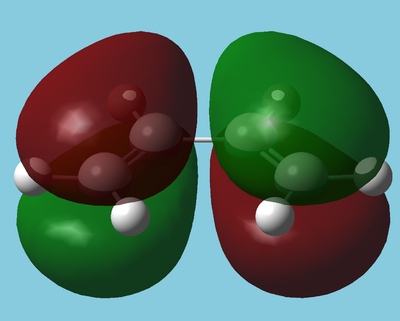

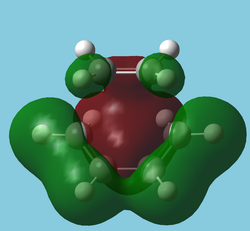

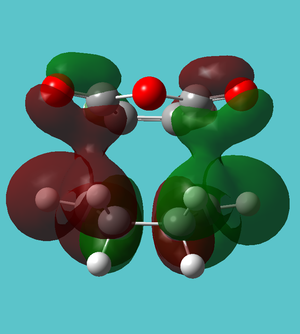

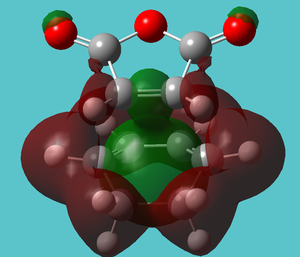

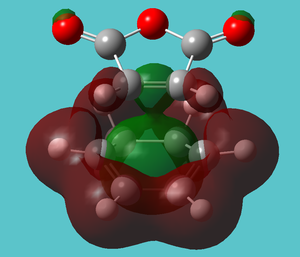

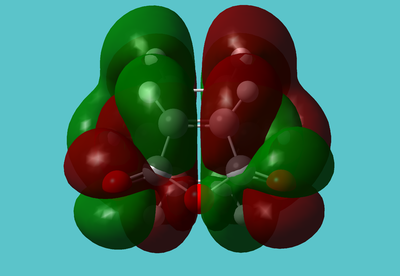

As expected, the antiperiplanar molecule has a lower energy. However, a quick MO study of the gauche form[1] (without frequency analysis, which is of course bad practise, but this is just to roughly investigate the posibility of an attractive interaction) reveals a very obvious attractive interactions between the two double bonds in many orbitals; the most striking being in the HOMO:

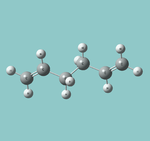

It may be possible to get a stronger interaction by aligning the double bonds better with a rotation about one of the C-C(=C) bonds. This means it may be worth investigating whether this yeilds a lower energy.

| Conformation | Model | Point group | Energy (a.u.) | DOI | Structure in Table |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gauche 2 |  |

C1 | -231.69266(122) | DOI:10042/to-13357 | gauche3 |

Indeed it does, presumably because of even better overlap between the double bond orbitals.

Frequency analysis of anti2

| Method | Model | Energy (a.u.) | Bond Lengths (A) | DOI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,2- | 2,3- | 3,4- | ||||

| HF/B3LYP (3-21G) |  |

-231.69253(521) | 1.32 | 1.50 | 1.55 | DOI:10042/to-13354 |

| DFT/B3LYP (6-31G(d)) |  |

-234.61171(463) | 1.33 | 1.50 | 1.55 | DOI:10042/to-13367 |

The structure obtained from the higher level calculation is very similar to that obtained from the lower. The energy however seems to be lower indicating some favourable interaction is underplayed or even omitted in the lower level calculation.

| Energy Type | Energy (a.u.) | Experimental equivalent |

|---|---|---|

| Sum of electronic and zero-point Energies: | -234.46920(7) | E(0K) = Eelec + Zero point energy |

| Sum of electronic and thermal Energies: | -234.46185(7) | E(298.15K, 1atm) = E + Evib + Erot + Etrans Thermal contribution from all degrees of freedom |

| Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies: | -234.46091(3) | H = E + RT Incorporates RT correction for enthalpy term |

| Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies: | -234.50080(6) | G = H - TS Entropic Contribution giving free energy |

- ↑ Rough MO study of first gauche conformer (no frequency analysis) DOI:10042/to-13356

- ↑ Frequency Analysis of anti2 DOI:10042/to-13368

Transition state

Using Berny Methods

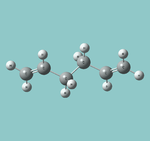

If the rough geometry of the transition state is known, it is possible to attempt optimise it by simply modelling the transition structure. For the Cope Rearrangement, it is possible to do this using two three carbon fragments, which were individually optimised with a low level method[1]:

|

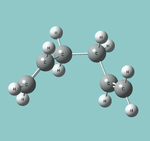

From this point, there are two possible approaches. If the modelled species is a good enough representation of the tranition state, then force constants can be calculated and ammended at every step and the optimisation proceeds up the curvature of the potential energy surface until the transition state is reached. However, if may instead be necessary to perform an extra optimisation if the transition state is not accurately depicted. The reaction coordinate is fixed (bonds that break or form) so the reaction does not "proceed" during the optimisation, as it were, and the structure optimised[2].

|

The structure obtained is very similar to the input, indicating the TS drawn is acceptable. The main difference is the fragements are no longer planar (individual fragments go from C2v to Cs). The transition state calculation is then carried out by differentiating along the reaction coordinate only.

| Using Full Hessian Force Matrices |

Differentiating Along the Reaction Coordinate | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animation |

|

| ||||||

| DOI | DOI:10042/to-13462 | DOI:10042/to-13463 | ||||||

| Frequency (cm-1): | -817 | -818 | ||||||

| Total energy (a.u.): | -231.61932(150) | -231.61932(198) | ||||||

| "Experimental" Values (a.u.) | ||||||||

| Sum of electronic and zero-point Energies: | -231.46670(5) | -231.46669(6) | ||||||

| Sum of electronic and thermal Energies: | -231.46134(4) | -231.46133(7) | ||||||

| Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies: | -231.46040(0) | -231.46039(2) | ||||||

| Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies: | -231.49455(9) | -231.49454(7) | ||||||

Both calcuations give very similar results; identical to 4 decimal places (except for the free energies which vary slightly more). The full Hessian calculation will be slightly more reliable as it performs calculations across the entire molecule, while the other method focuses on one path; the path of the reaction. This does have one huge benefit, however, as in larger molecules which may have extremely complex potential energy surfaces, the exact path of the "transition" can be mapped, which prevents the calculation dipping into another irrelevent potential well.

- ↑ HF/3-21G optimisation of fragment DOI:10042/to-13470

- ↑ Optimised structure with frozen reaction coordinate DOI:10042/to-13492

QST2

The QST2 method is very useful, in that even the rough transition structure does not need to be known. The reactants and products are given, and a reaction path and transition structure is guessed. This has an obvious advantage over the previous method, but the method is not always successful. This is shown below, with thwo conformations running through the same process. One is an antiperiplanar configuration[1]. This guess made to reach the transition state involves a translation of one half of the molecule on to the other giving the chair transition state with similar (but not exact) energies to the previous calculations. The method ignored the possible rotation to give the boat and instead calculated the "lower energy" pathway. The translation as shown would in fact have an extrememly high energy barrier, but gives a perfectly acceptable chair transition state. From the point of view of the calculation, which treats the atoms as unbonded points, this translation is acceptable as presumably, while determining the transition state, not many electonic factors (and hence bonds, hybridisations etc..) are incorporated until a viable transition state is obtained. Or at least it ignores this exceedingly high energy barrier.

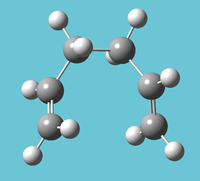

The other conformation has been manually changed to match the boat transition state more closely. This does yield the boat transition state.

| Inital Conformation | Antiperiplanar | Distorted Towards Boat | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animation |

|

| ||||||

| Chair | Boat | |||||||

| DOI | DOI:10042/to-13496 | DOI:10042/to-13497 | ||||||

| Frequency (cm-1): | -818 | -840 | ||||||

| Total energy (a.u.): | -231.61932(243) | -231.60280(299) | ||||||

| "Experimental" Values (a.u.) | ||||||||

| Sum of electronic and zero-point Energies: | -231.46669(9) | -231.45092(6) | ||||||

| Sum of electronic and thermal Energies: | -231.46134(0) | -231.44529(8) | ||||||

| Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies: | -231.46039(6) | -231.44435(4) | ||||||

| Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies: | -231.49520(5) | -231.47977(1) | ||||||

The major issue with this technique is the hydrogen labelling. It is easy to see where a specifc carbon goes on through the reaction. All these much retain their hydrogen (of course) which in itself is easy to deal with. However, all the carbon centers in affect become chiral because if one hydrogen pair is the wrong way round about one carbon, the program may assume a different direction of attack, making the reaction impossible and causing the calculation to fail.

- ↑ QST2 Method on antiperiplanar conformations DOI:10042/to-13654

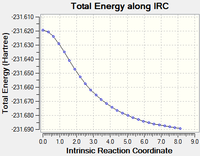

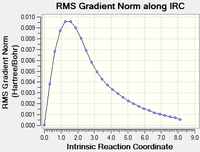

IRC

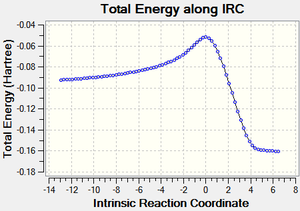

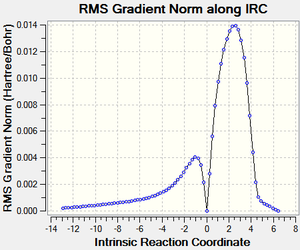

IRC calculations allow us to follow a reaction as it progresses and gives an energy diagram. For this reaction, it is symmetric as the reactants and products are identical.

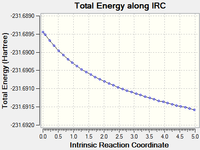

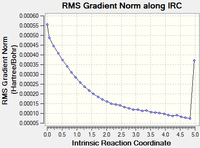

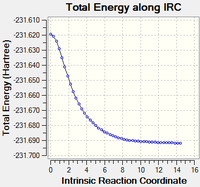

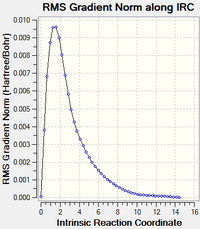

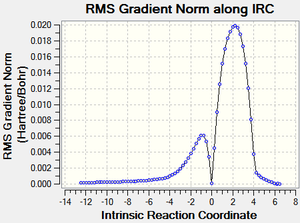

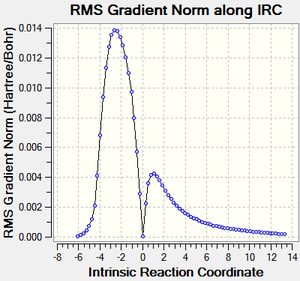

Running the first calculation with 50 steps does not yield a minimum (RMS gradient=0). There are three methods by which the final structure can be obtained:

| Method Description | "CPU Time" | Final structure obtained | Energy Diagram | RMS Gradient |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original IRC calculation DOI:10042/to-13651 |

10 minutes 38.2 seconds | Not finished |  |

|

| ||||

| Continuing the calculation where it left off DOI:10042/to-13653 |

16 minutes 56.8 seconds | gauche2 |  |

|

| ||||

| Repeating but with calculation of force constants at every step DOI:10042/to-13652 |

12 minutes 32.4 seconds | gauche2 |  |

|

|

The third method is repeating the calculation with more steps.

Continuing the calculation did give a final conformation, but in the last step it seemed to reach a stationary point and may have started to head toward another conformation.

The 3rd step, calculating the force constant at every step was by far the best method, as it approached the "product" in only a few steps, though it did take slightly longer than the initial IRC calculation, according to "CPU time". All converged to the same conformation, gauche2.

Higher Optimisations of Transition States

| Chair | Boat | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-21G | 6-31G* | 3-21G | 6-31G* | |

| DOI | DOI:10042/to-13462 | DOI:10042/to-13655 DOI:10042/to-13656 |

DOI:10042/to-13497 | DOI:10042/to-13504 |

| Frequency (cm-1): | -817 | -569 | -840 | -530 |

| Total energy (a.u.): | -231.61932(150) | -234.55693(218) | -231.60280(299) | -234.54309(307) |

| Thermodynamic Values (a.u.) | ||||

| Sum of electronic and zero-point Energies: | -231.46670(5) | -234.41487(8) | -231.45092(6) | -234.40234(2) |

| Sum of electronic and thermal Energies: | -231.46134(4) | -234.40895(0) | -231.44529(8) | -234.39600(8) |

| Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies: | -231.46040(0) | -234.40800(6) | -231.44435(4) | -234.39506(3) |

| Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies: | -231.49455(9) | -234.44311(8) | -231.47977(1) | -234.43175(2) |

The 6-13G* method gave exactly the same values for the chair transition state derived from both methods despite initially being different values. The Chair transition state is 39 kJmol-1 more stable than the boat (ΔG) according to 3-21G and 30kJmol-1 according to 6-31G*.

The Reaction Itself

| Conformation: | anti2 | Chair | Boat | ΔEchair | Experiment | ΔEboat | Experiment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sum of electronic and zero-point Energies (a.u.): | -234.46920(7) | -234.41487(8) | -234.40234(2) | 34.09 | 33.5±0.5 | 41.96 | 44.7±2.0 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal Energies (a.u.): | -234.46185(7) | -234.40895(0) | -234.39600(8) | 33.20 | 41.32 | ||

| Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies (a.u.): | -234.46091(3) | -234.40800(6) | -234.39506(3) | ||||

| Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies (a.u.): | -234.50080(6) | -234.44311(8) | -234.43175(2) | ||||

The predicted energies are higher than experiment for the chair, and lower for the boat. However, they are very good guesses considering these calculations are derived from a completely theoretical basis, and have successfully shown the expected trends.

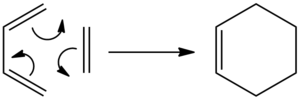

The Diels Alder Reaction

Prototype Reaction

Studying the very simplest Diels Alder reaction will allow us to better understand more complex scenarios.

The following reaction is investigated:

The substituents are symmetric and hence there is no ambiguity regarding face of approach.

Initially, the structure of cis-butadiene is optimised using AM1[1] and the transition structure was guessed as follows.

|

The ethene molecule was positioned approximately 2A from the butadiene and its hydrogen were bended slightly away. The entire structure was then symmetrised to Cs and this structure was then submitted for AM1 optimisation and frequency analysis[2]. The following resulted, which was further optimised using 6-31G*:

| AM1 | 6-31G* | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animation |

|

| ||||||

| .log File | View | View | ||||||

| Frequency (cm-1): | -956 | -525 | ||||||

| Total Energy (a.u.): | 0.11165(518) | -234.54389(655) | ||||||

| Thermodynamic Values (a.u.) | ||||||||

| E(0K) | 0.25327(9) | -234.40332(5) | ||||||

| E(298.15K) | 0.25945(5) | -234.39690(7) | ||||||

| H | 0.26040(0) | -234.39596(3) | ||||||

| G | 0.22401(9) | -234.43289(2) | ||||||

The two methods give drastically different values. The AM1 calculations are semi-empirical and so would not give meaningful predictions for thermodynamic values; these numbers have no real significance at the moment as there are no other AM1 calculations to make comparisons to.

The vibrations show both bonds forming symmetrically at the same time, which is the reason behind the stereospecifity of the reaction. The next vibration at 136cm-1 is antisymmetric and if was down a potential gradient (i.e. a negative frequency) it could theoretically result in asynchronous bond formation.

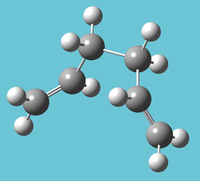

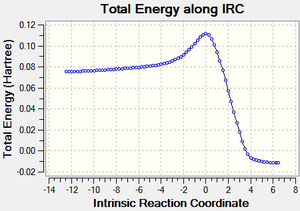

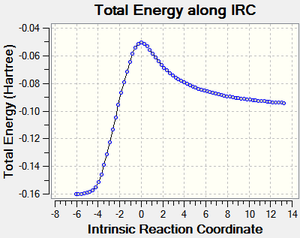

The physical reaction can be observed with IRC[3] calculations:

| Reaction Profile | RMS Gradient | The Reaction |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

The reaction profile nicely demonstrates the the activation energy and the formation of the more stable products.

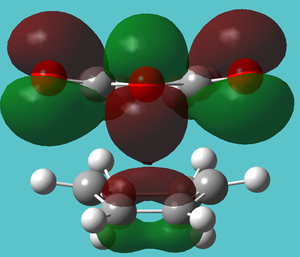

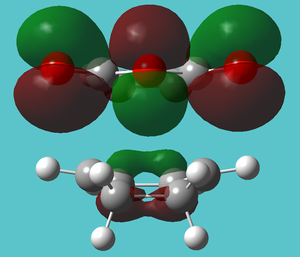

This course of reaction can be interpreted through MO analysis.

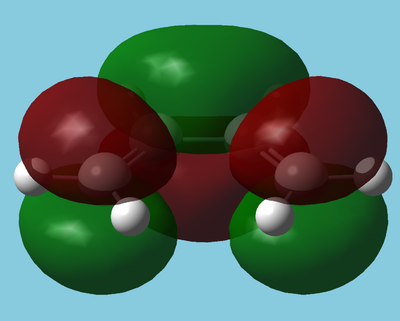

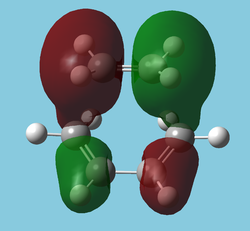

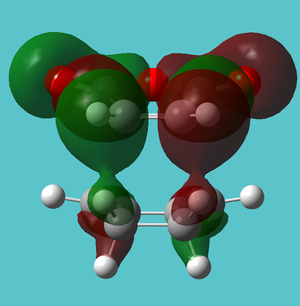

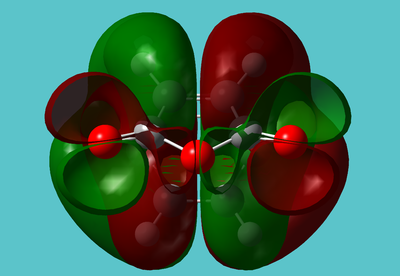

The LUMO and HOMO of butadiene[4] are shown below:

| HOMO | LUMO |

|---|---|

|

|

| Antisymmetric | Symmetric |

The HOMO is antisymmetric with respect to the plane and hence can interact with the alkenes antibonding orbital (LUMO). The LUMO is also in the correct symmetry to interact with the bonding orbital (HOMO) of the alkene, which is the predominant interaction in inverse electron demand Diels Alder reactions.

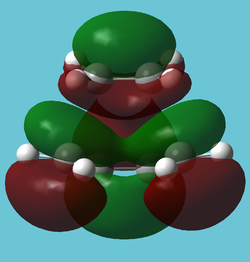

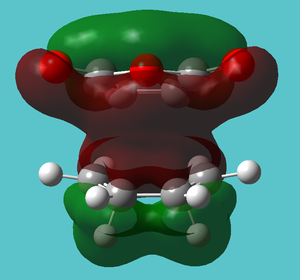

The "molecular" orbitals[5] of the Transition State can also be used to observe the movement of electron density throughout the reaction.

| HOMO-10 | HOMO-12 | HOMO-14 |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Symmetric | Antisymmetric | Antisymmetric |

| Interestingly shows electron density donation from the alkene. May be "forming" the sigma network. A similar interaction exists in benzene. | Nicely depicts the antibonding MO of ethene taking on some sigma character. The ethene LUMO is now in a very low energy orbital. | As left, the shows the C-C bonds forming but this time from donation from the diene. One could see this as the "bonding" orbital (more accurately Ψ+Ψ) of left, the "antibonding" orbital(Ψ-Ψ). |

| LUMO |

|---|

|

| LUMO of butadiene interacting with HOMO of ethene. Compared to to butadiene's LUMO, there is a "closing" interaction (front) which could be a product of the ring formation. |

The HOMO of the transition state is symmetric about the central plane and is therefore suprafacial. This agrees with the prediction that a 6 electron system under thermodynamic control will undergo a suprafacial transformation. This also predicts a Hückel transition state (see below).

The reaction is allowed because no orbitals of the same symmetry "cross" in energy. The diagram shows the product as completely planar cyclohexene, which is the conformation formed straight after. After its formation, the structure twists into a lower confomration (which incidentally has several Möbius orbitals).

In the above diagram, in the initial product there are 6π electrons and 2σ electrons. From convention, this is a 2+4 electrocyclic addition and hence a 6 electron reaction, but on looking at the transition state, it may be more accurate to describe it as a 10 electron reaction, with another pair being introduced from the sigma system (which still gives the correct prediction of a Hückel transition state). The diagram shows 2 "degenerate" pairs (within 0.01 Hartrees), though it must be noted that these are not formally degenerate. This is done to compare the transition state to the benzene aromatic system. It does indeed have similarities in is degeneracies and form, but it is filled above the traditional "zero mark" (bonds become destablising). In the transition state above however, all of the orbitals (including the unfilled orbital) shown are at least mildly stablising.

This may show that a direct comparison to benzene may not be completely accurate, but it is for the most part useful. A better way of explaining why a system prefers a Hückel over a Möbius transition state would be to ignore the absolute energy levels of benzene (or any other Hückel system) and focus on whether they would be symmetrically filled, i.e. a 4n system would result in a biradical as the energy levels become (almost) degenerate. However, this treats the transitions state as a non-transient species, and a more realistic argument is that a filled orbital would "cross" an empty orbital giving a product molecule in a higher electronic energy state, which is not allowed. Light excitation into higher electronic states would avoid this and hence be allowed (4n systems pass through a Hückel transition state if excited with light).

The Reaction of Cyclohexadiene and Maleic Anhydride

Finding the Transition Structure

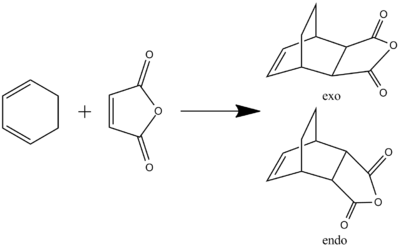

The following reaction will now be investigated:

Unlike the previous reaction, there are now two distinct faces of approach.

Initially, the structure of cyclohexadiene[1] and maleic anhydride[2] were optimised using AM1. These were then arranged into guess transition structures in the same manner as before. In addition to the previous distortions, the ring was also bent towards the anhydride.

| Exo | Endo | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

| Exo | Endo | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animation |

|

| ||||||

| .log | View | View | ||||||

| Frequency (cm-1): | -812 | -807 | ||||||

| Thermodynamic Values (a.u.) | ||||||||

| E(0K) | 0.13488(8) | 0.13349(4) | ||||||

| E(298K) | 0.14488(7) | 0.14368(3) | ||||||

| H | 0.14583(1) | 0.14462(7) | ||||||

| G | 0.09912(9) | 0.09735(0) | ||||||

| Exo | Endo | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animation |

|

| ||||||

| DOI | DOI:10042/to-13677 | DOI:10042/to-13678 | ||||||

| Frequency (cm-1): | -449 | -447 | ||||||

| Thermodynamic Values (a.u.) | ||||||||

| E(0K) | -612.49801(3) | -612.50214(2) | ||||||

| E(298K) | -612.48766(1) | -612.49178(8) | ||||||

| H | -612.48671(7) | -612.49084(4) | ||||||

| G | -612.53426(5) | -612.53833(0) | ||||||

Both methods give the endo transition state as lower in energy (G); AM1 gives by 4.7 kJmol-1 and 6-31G* by 10.7 kJmol-1. The transition structures themselves are fairly similar (except of course the orientation of the anydride). The exo product may have slighly more steric repulsion due to the anyhydride being positioned closer to CH2CH2 as opposed to CHCH, causing repulsion between the H and the anhydride ring.

IRC calculations

| Reaction Profile | RMS Gradient | Animation |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| DOI:10042/to-13712 | ||

| Reaction Profile | RMS Gradient | Animation |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| DOI:10042/to-13711 | ||

The endo approach seems like it has least hindered approach as it comes down on to the planar alkene. This also shows both reactions are exothermic, as expected (2π form 2σ bonds).

MO analysis

In the table below, "bonding" refers to an interaction between both components. Omitted orbitals appear very similar between both transition states.

| MO | Endo | Exo |

|---|---|---|

| HOMO | Bonding OCOCO fragment has more electron density |

|

| HOMO-1 | Bonding OCOCO fragment has more electron density | |

| HOMO-2 | Bond forming | |

| HOMO-3 | All three oxygens interacting with each other | |

| HOMO-4 | Slight secondary orbital overlap | |

|

| |

| HOMO-5 | Bond forming with same energy (-0.34491 Hartree) despite (on close inspection) looking quite different | |

| HOMO-7 | Both Bonding, exo lower in energy | |

| HOMO-10 | Both Bonding, exo lower in energy | |

| HOMO-13 | Favourable C-H...CO interaction | |

| ||

| HOMO-16 | Hydrogen Van der Waals attraction | |

|

||

| HOMO-17 | Large amount of electron density on maleic anhydride | Significantly less |

| HOMO-18 | Bonding | |

| HOMO-19 | Strong interaction with OCOCO and bonding | Not present |

|

| |

| HOMO-20 | Bonding | |

| HOMO-21 | Aromatic character (-0.53480 Hartree) | Higher in energy (-0.53392 Hartree) |

|

| |

| HOMO-23 | Bonding, stronger for endo | |

| HOMO-26 | Bonding, stronger for endo | |

| HOMO-29 | Bonding, slightly stronger for endo | |

| DOI | DOI:10042/to-13728 | DOI:10042/to-13729 |

Interestingly, all bond forming higher orbitals are more stable for the exo form where an equivalent orbital exist. This swaps below the "aromatic" orbital. The endo does have an extra bond forming orbital (HOMO-2) and there are additional stablising effects for both species from the sp3 hybridised carbons opposite the formed C=C; for endo this is a strong H-H attractive interaction (HOMO-16) and for the exo it is, in effect, a pair of "hydrogen bonds" between a C-H and the carbon in a C=O bond.

The most important interactions in terms of the selective formation of the endo product are in HOMO-19 and to a lesser extent HOMO-4. These clearly show an overlap with the C=C-C=C and the (O=C)O(C=O) components of the reactants. This lowers the energy of the endo transition state relative to the exo, making the endo the kinetic product.

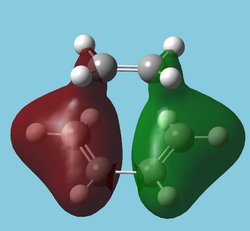

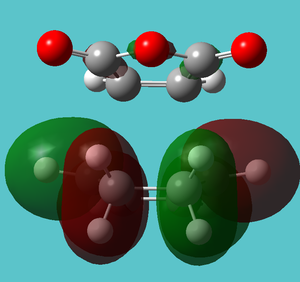

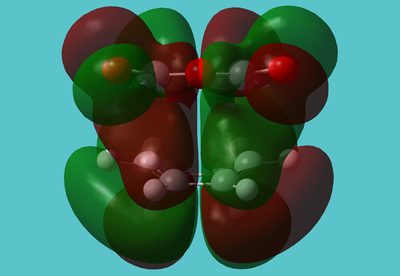

Looking specifically at the (O=C)O(C=O) fragment of the endo HOMO:

This fragment is completely out of phase with the rest of the molecule, with a node running down the middle:

The lone pairs seem slightly "twisted". It almost seems as if simply swapping the phase of the oxygen lone pairs would stablise the molecule:

There is also a node almost running along the C-O-C portion of the molecule. This may be indicative of the instability and reactivity of anhydrides; the HOMO acts to to "break" this part of the molecule, almost like an antibonding orbital.

Quantitative Energy Profile

| Reactants | Transition States | Products | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclohexadiene | Maleic Anhydride | Total Reactants | Exo Transition State | Endo Transition State | Exo Product | Endo Product | |

| E(0K) | -233.29610(6) | -379.23365(6) | -612.52976(2) | -612.49801(3) | -612.50214(2) | -612.56938(1) | -612.57207(1) |

| E(298K) | -233.29093(4) | -379.22847(3) | -612.51940(7) | -612.48766(1) | -612.49178(8) | -612.55997(8) | -612.56260(6) |

| H | -233.28998(9) | -379.22752(9) | -612.51940(7) | -612.48671(7) | -612.49084(4) | -612.55903(3) | -612.56166(1) |

| G | -233.32435(7) | -379.26272(8) | -612.58708(5) | -612.53426(5) | -612.53833(0) | -612.60428(2) | -612.60717(9) |

| File/ DOI |

View | DOI:10042/to-13744 | - | DOI:10042/to-13677 | DOI:10042/to-13678 | DOI:10042/to-13748 | DOI:10042/to-13747 |

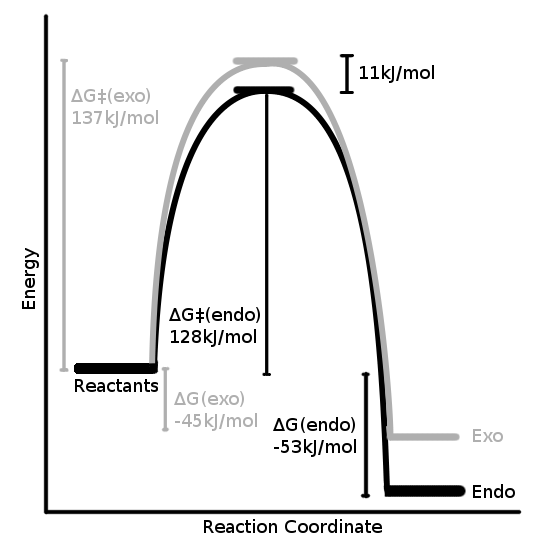

| ΔG‡Exo | ΔG‡Endo | ΔGRExo | ΔGREndo |

|---|---|---|---|

| 138.68 | 128.01 | -45.15 | -52.76 |

Despite the exo product in Diels Alder reactions usually being the most thermodynamically stable[3], in this reaction this is not the case. This makes sense as the exo product does seem to exhibit the repulsions mentioned before, involving the alkylic bridge.

| Exo | Endo | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

In other cases[3], where a cyclopentadiene is used instead for example, this repulsion would be reduced as there would be only one hydrogen in the bridge and it would be centered and the situation would arise where the kinetic and thermodynamic products are different.

- ↑ AM1 Optimisation of Cyclohexadiene

- ↑ AM1 Optimisation of Maleic Anhydride

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Cooley, J. H.; and Williams, R.V; J. Chem. Educ., 1997, 74 (5), p 582 DOI:10.1021/ed074p582