Rep:Mod:RLInorganic

EX3 Section

BH3 Optimisation

3-21G

A molecule of BH3 was first created using GaussView 5.0. The central Boron atom was fixed in position, allowing the B-H bond distances to be set to 1.53, 1.54 and 1.55 angstrom respectively to break the symmetry of the molecule. This was then optimised using the Optimisation Job Type, B3LYP method and 3-21G basis set. The optimisation process comprises of two parts: The self-consistent field (SCF) part of the calculation proceeds by assuming a given position for the nuclei, allowing the Schrödinger equation to be solved for the energy and electronic density as a function of this position. The OPT part of the calculation then repeats the SCF calculation at various different geometries until the lowest energy configuration is found. The method determines the type of approximations made in solving the Schrödinger equation, and the basis set determines the accuracy. The completed optimisation for BH3 is shown below.

Optimisation log file here

A link to the .log file, the "Item" section of the output, a snapshot of the results summary and a rotatable Jmol image is included above for the completed job. Two checks were also made to ensure the optimisation had been completed correctly, the first of which is to check that the gradient in the summary is very close to 0 as seen in the case above. The second check is to look in the "Item" part of the .log file to check whether the forces have converged (YES in the converged section of the table). For this optimisation, both these requirements are fulfilled so the optimisation was successful.

6-31(d,p)

After running a calculation to obtain a basic structure using the low accuracy 3-21G basis set, a more accurate 6-31(d,p) basis set was used to obtain a better optimisation. The optimisation job was checked for successful convergence in the same manner as the last calculation.

Optimisation log file here

| summary data | convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000012 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000008 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000064 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000039 0.001200 YES |

|

A much lower energy value of -26.6153236 a.u. was obtained using the 6-31(d,p) basis set, compared to a value of -26.4622637 a.u. from the 3-21G basis set, corresponding to a difference of 0.1530599 a.u. (401.86 kJ/mol). However, as the two basis sets differ in the accuracy of their calculation, the result from using the previous lower level 3-21G basis set cannot be compared with this value so it cannot be concluded that the 6-31(d,p) basis set optimised structure is more stable than the 3-21G optimised structure.

|

|

It was expected that the D3h point group would be obtained for this molecule after two optimisations, however it was found not to be the case due to the accuracy of the program. The bond lengths for each B-H bond in the molecule as well as the H-B-H bond angles were analysed and found to give the same values when taken to the degree of accuracy expected, and so we can consider the system to have the correct symmetry for the level of analysis applied.

GaBr3 Optimisation

Since Ga and Br are both heavy elements with many electrons, these experience relativistic effects which cannot be accounted for using the standard Schrödinger equation. Instead, by assuming that the valence electrons are the dominant factor in bonding interactions and remain essentially unaffected by core electrons, these core electrons of an atom can be modelled by a function called a pseudopotential (PP), allowing the calculation to be performed normally upon the valence electrons. The LANL2DZ medium level basis set was used, which is of medium accuracy taking into consideration the balance between computational time and quality. The calculation was run on the High Performance Computer (HPC) service, to reduce the calculation times.

The 6-31G(d,p) basis set optimised BH3 structure was first opened, and then modified by replacing the B and H atoms with Ga and Br atoms respectively before running the calculation. The symmetry of the molecule was constrained to the D3h point group, with the molecule bond lengths and bond angles tabulated after optimisation.

Optimisation log file here

| summary data | convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000000 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000000 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000003 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000002 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-1.282677D-12

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

|

|

BBr3 Optimisation

The BBr3 molecule contains two heavy Br atoms and a relatively light B atom which does not require the use of a pseudopotential as it does not have a large number of non-contributing core electrons. To allow for this, the input file was modified to use the 6-31G(d,p) basis set for the B atom, and the LANL2DZ basis set for the Br atoms (Input file can be viewed from the DOI). As for GaBr3, the bond lengths and angles were tabulated.

Optimisation log file here

| summary data | convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000016 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000009 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000101 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000054 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-1.361370D-09

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

|

|

Analysis

| BH3 | BBr3 | GaBr3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| r(E-X) (Å) | 1.19 | 1.93 | 2.35 |

| r(E-X) (Å) Literature[1] | 1.19 | 1.89 | 2.25 |

| θ(X-E-X) (°) | 120.0 | 120.0 | 120.0 |

Comparison of molecules through bond length

Comparing BH3 and BBr3, the difference is evidently the complete substitution of the of the ligands. Both H and Br are considered as X type ligands, donating a single electron to the central B atom. However, Br atoms have a much larger atomic radius than H atoms, due to the fact they contain more electrons. This increased size rationalises the increase in bond length observed, as the sum of the covalent radii of B and Br is much larger than B and H (covalent radii: H 0.32 Å, B 0.84 Å, Br 1.17 Å)[1].

Taking a sum of the atomic radii, the expected B-H bond length would be 1.16 Å, and that of B-Br 2.01 Å from the literature. However, the calculated value for the B-H bond is slightly longer than expected, whereas the B-Br bond is slightly shorter. This can be rationalised by considering the overlapping of orbitals in the formation of the bond; since Br is more similar in size to B this will increase the bonding interaction between the two atoms and therefore shorten the bond length to the observed value of 1.93 Å. Conversely, since B and H are less similar in size their overlap will be weaker and therefore the bond will lengthen to the observed value of 1.19 Å.

BBr3 and GaBr3 differ in the substitution of the central atom. Ga is below B in the periodic table, and is therefore much heavier and larger (covalent radius 1.23 Å)[1]. However, since Ga and B are in the same group, their valence electron behaviour is expected to be similar. The larger size of the Ga atom contributes to the extension of the Ga-Br bond compared to the B-Br bond by simple comparison of the atomic radii, resulting in an increase of the bond length by 0.42 Å from 1.93 to 2.35 Å. By doing a similar comparison to changing the ligand size and adding together the covalent radii from literature, the B-Br length is found to be 2.01 Å while the Ga-Br length is 2.40 Å. This means that the Ga-Br bond is much shorter than expected, even more so than the B-Br bond. This is due to the fact that Ga is closer to Br in size than B (same row), and so the orbital overlap will be more favourable.

Considering the Ga and B atoms, these both belong to Group 13 of the periodic table. Going down the group, the s-p orbital separation increases due to the s orbital penetrating closer to the nucleus and experiencing a greater nuclear charge, which in turn increases the amount of energy required to promote an electron across the s-p gap. This inert pair effect, also taking into account bond energies, results in various Ga compounds existing in the +1 and +3 oxidation states, whilst B compounds exist exclusively in the +3 oxidation state. This depends on the relative energy required to promote an electron across this s-p gap, and the bond energy released from forming 2 new bonds.

Bonding discussion

A bond can be considered as favourable attraction between the nuclei of atoms for electrons. The repulsion of the nuclei involved is balanced by the attraction of the nuclei for electrons in order for a bond to be formed. This balancing results in the electrons and nuclei organising themselves to form a system in which there are no net forces and hence minimum energy, with a seperation known as the bond distance.

By taking into account the number of bonding electron pairs, we can use the bond order as a determination of relative bond strength. A larger number of bonding pairs would indicate a strong bond, whereas a small number indicates a weak bond. However, the weakest form of bonding is due to Van der Waals forces, or more specifically London dispersion forces. The London Dispersion force is a weak intermolecular force arising from instantaneous dipole formation in molecules, which can form in molecules without a permanent dipole moment. These bonding interactions are generally of the order 1-10 kJ/mol. Covalent bonds are of medium strength, and an example of this would be C-H with a bond enthalpy of 432 kJ/mol. A triple bond in a nitrile group has a bond order of 3, and can be considered a strong bond, this has a bond enthalpy of 887 kJ/mol.[2]

The program used for these calculations (Gaussview) determines a bond strictly by the distances between two atoms. Therefore, for certain analyses performed whilst the bond will still exist the program criteria for the bond distance is not fulfilled, so a bond will not be drawn.

Frequency Analysis

BH3 Frequency

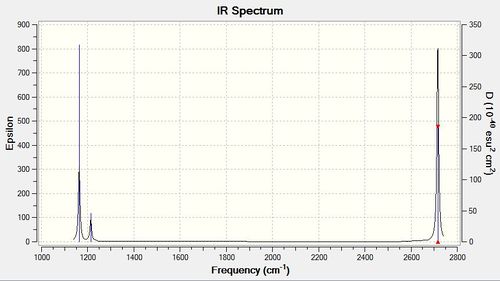

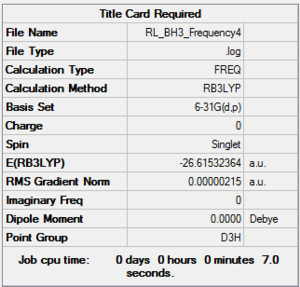

The calculation setup for the 6-31(d,p) optimised BH3 basis set was modified by changing the job type from optimisation to frequency analysis.

Frequency file: here

| summary data | low modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -11.7227 -11.7148 -6.6070 -0.0010 0.0278 0.4278 Low frequencies --- 1162.9743 1213.1388 1213.1390 |

The line listed as low frequencies refers to the motions of the centre of mass of the molecules. In order to determine whether the frequency analysis is of the required quality, this value is required to be within ±15 cm-1. Therefore this frequency analysis is of a sufficient standard.

| Wavenumber | Intensity | IR active? | type |

| 1163 | 93 | yes | bend |

| 1213 | 14 | very slight | bend |

| 1213 | 14 | very slight | bend |

| 2583 | 0 | no | stretch |

| 2716 | 126 | yes | stretch |

| 2716 | 126 | yes | stretch |

Despite the presence of six vibrational modes, as expected using the 3N-6 rule for 4 atoms, only three peaks are visible in the IR spectrum. The vibration present at 2583 cm-1 is not visible in the IR spectrum due to its totally symmetric vibration resulting in no change in dipole moment. Two degenerate bending vibrations have the same frequency value at 1213 cm-1, therefore instead of seeing two distinct peaks in the IR spectrum, we see one more intense peak. The same occurs for the stretching vibrations at 2716 cm-1.

GaBr3 Frequency

The same frequency analysis was conducted for the GaBr3 6-31G(d,p) basis set optimised structure, ensuring the results would be comparable later with the BH3 vibrations. Frequency file: here

| summary data | low modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -0.5252 -0.5247 -0.0024 -0.0010 0.0235 1.2010 Low frequencies --- 76.3744 76.3753 99.6982 |

Again the low frequencies table was checked to probe the quality of the calculation. The values were found to be within ±2 cm-1, so the accuracy of the calculation was acceptable.

| Wavenumber | Intensity | IR active? | type |

| 76 | 3 | very slight | bend |

| 76 | 3 | very slight | bend |

| 100 | 9 | very slight | bend |

| 197 | 0 | no | stretch |

| 316 | 57 | yes | stretch |

| 316 | 57 | yes | stretch |

Three peaks are observed in the IR spectra, corresponding the the degenerate vibrational bends at 76 cm-1, single vibrational bend at 100 cm-1, and degenerate vibrational stretches at 316 cm-1, all involving a change in the dipole moment. However, the symmetric stretch at 197 cm-1 involves no such change and is therefore not observed.

Frequency Analysis

| BH3 | GaBr3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wavenumber(cm-1) | Intensity | Ir Active? | type | Wavenumber (cm-1) | Intensity | IR Active? | type |

| 1162 | 93 | yes | bend | 76 | 3 | very slight | bend |

| 1213 | 14 | very slight | bend | 76 | 3 | very slight | bend |

| 1213 | 14 | very slight | bend | 99 | 9 | very slight | bend |

| 2582 | 0 | no | stretch | 197 | 0 | no | stretch |

| 2715 | 126 | yes | stretch | 316 | 57 | yes | stretch |

| 2715 | 126 | yes | stretch | 316 | 57 | yes | stretch |

In both spectra, there is a total of six vibrational modes due to the 3N-6 rule : 3*4-6 = 6. As discussed, only three peaks appear on each spectrum due to a set of degenerate bending vibrations, a set of degenerate stretching vibrations, and an IR active bending vibration, with the totally symmetric stretching vibration not appearing due to no change in dipole moment. As expected the stretching frequencies require a much higher energy than the bending frequencies.

To make a comparison between the IR spectra observed for BH3 and GaBr3, background theory can be used to rationalise the observed effects. According to Hooke’s Law which governs the vibrations, the frequency can be calculated by approximating the atoms as two masses connected together by a spring with a spring constant 'k' as shown in the below equation.

c is the speed of light, and μ is the reduced mass of the system given by:

By considering the reduced mass of the vibrations, it is clear the the Ga-Br values will be much higher than those of B-H as the atomic masses of Ga and Br are far higher than those of B and H. Therefore, it would be expected that the IR frequencies obtained from the Ga-Br vibrations would be much lower than those of B-H, which matches the computational result. The second factor is to consider the value of the spring constant k which can be considered as a measure of bond strength. Larger values of k result from shorter, stiffer bonds, and therefore will increase the IR frequencies observed. The BH3 molecule should therefore have a higher vibrational frequency due to it's shorter (and therefore stronger) bond compared with GaBr3 which was obtained from the optimisation, resulting in a higher k value.

Considering the A2’’ umbrella motion, these occur at vastly different frequencies for the BH3 (1163 cm-1) and GaBr3 (100 cm-1). This is accompanied by a difference in intensity of 93 and 9 respectively for the two molecules. For the BH3 umbrella vibration, the displacement vectors indicate that the central Boron atom remains almost stationary whilst the hydrogen atoms move, whereas in GaBr3, the displacement involves the central Ga atom moving and the Br atoms being displaced very little. This can be rationalised by considering the relative masses of the two atoms: In BH3, the central B atom is far heavier than the attached H atoms, whereas for the GaBr3 molecule the Br atoms have a greater mass than the Ga central atom. Since the lighter atom is expected to move in this motion, this umbrella motion behaves as expected. As previously mentioned, the umbrella motion of BH3 results in a higher frequency peak than the equivalent vibration in GaBr3 due to its higher bond strength (k) and lower reduced mass. The intensity of the BH3 vibration was found to be much higher than that of GaBr3, due to the motion of three H ligands about the central heavy B atom causing a larger change in dipole moment compared to only the central Ga atom moving with a lower change in dipole moment.

| Molecule | Umbrella Motion | Frequency (cm-1) | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|

| GaBr3 |  |

100 | 9 |

| BH3 |  |

1163 | 93 |

Purpose of Frequency Analysis

When a frequency analysis is computed, we take the second derivative of the stationary points corresponding to minima in energy found in our previous optimisation. If the frequencies are all positive, then we can say that a minimum stationary point has been found and the optimisation has been successful, whereas positive values would indicate a maximum had been found and the structure would need to be reoptimised. The six low frequencies observed in the correspond to the molecules centre of mass motion which are due to the rotational and translational movements of the molecule. Ideally, this value should be as close to 0 as possible, but this is highly dependent on the quality of the previous optimisation analysis. By applying higher level computations, these low frequencies should move closer and closer to 0.

As previously alluded to in the optimisation section, only results obtained using the same basis sets and method are directly comparable. The basis set determines the number of functions which are used to run the calculation, in which a larger number of functions used will improve the accuracy but increase the computational time. The method used gives the level of approximation used for the Schrödinger equation calculation, so the effect of running an optimisation calculation is to generate an idealised structure from the potential energy surfaces supplied by the basis set. Therefore, to compare different optimised structures from different basis sets will give no meaningful results. In all calculations, the method and basis set must be kept constant to be able to compare and contrast results.

BH3 MO Analysis

MO file: here

When considering LCAO generated orbitals compared with the generated MO's from the calculation, they differ distinctly in that the MO's combine the orbitals together in a delocalised manner across the entire molecule, whereas the idealised LCAO orbitals show discrete fragment orbitals from each contributing atom. By considering the first bonding 2a1' MO in the diagram above, from LCAO the 3H fragment from combination of the H atoms in the molecule is combined with the 2s orbital of the B atom, with the orbital depicted as four discrete orbitals with the 3H fragment having a larger contribution due to it being closer in energy to the totally symmetric MO than the 2s B fragment orbital. The same computed MO matches this symmetry as only one phase is observed, but now it is a single delocalised orbital covering the entire molecule. Whilst the LCAO method is very useful in considering which orbitals on which atom contribute to the MO and can give a qualitative approximation of what the actual MO may look like, in reality the calculated MO picture is a far better depiction as the electron density must be shared across the molecule for bonding to occur and is not always localised to each individual atom.

NH3 MO Analysis

An NH3 molecule was optimised using the 6-31G(d,p) basis set followed by a frequency analysis. All checks were made to ensure that the jobs had been completed to the required standard.

Optimisation log file here

| summary data | convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000006 0.000015 YES RMS Force 0.000004 0.000010 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000012 0.000060 YES RMS Displacement 0.000008 0.000040 YES Predicted change in Energy=-9.846061D-11 Optimization completed. |

|

Frequency file: here

| summary data | low modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -0.0129 -0.0016 -0.0012 7.0768 8.0933 8.0936 Low frequencies --- 1089.3840 1693.9368 1693.9368 |

The low frequencies can be seen to be within the range of ±15 cm-1, therefore the optimisation is of sufficient quality.

| wavenumber | Intensity | IR active? | type |

| 1089 | 145 | yes | bend |

| 1694 | 14 | very slight | bend |

| 1694 | 14 | very slight | bend |

| 3461 | 1 | very slight | stretch |

| 3590 | 0 | no | stretch |

| 3590 | 0 | no | stretch |

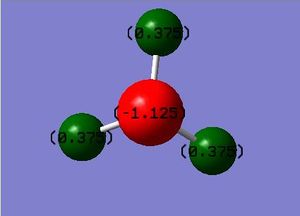

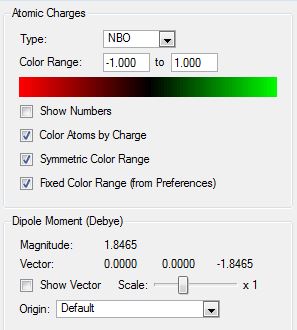

NBO Analysis

A population analysis was carried out to obtain a charge distribution for the molecule. An image of this charge distribution is shown below.

Population analysis log file here

The three charges on the H atoms (green in the image above) were found to be equivalent (-0.375), with the nitrogen found to have a charge of -1.125. Since nitrogen is far more electronegative than hydrogen, it is expected to have this more negative charge as well as have a charge of a higher magnitude, as there are three H atoms to one N atom. Since the overall molecule is neutral, addition of all the charges gives a value of 0 as expected.

The non-core occupied orbitals of NH3 are shown in the following table. Due to the level of MO calculation for the non-occupied orbitals, unless we are making a direct comparison to LCAO generated orbitals, these orbitals are often very approximate and generated from simply changing the phase of the corresponding bonding orbital, so are not very meaningful.

| MO | Picture |

|---|---|

| a1' |

|

| e' |

|

| e' |

|

| a1 |

|

NH3BH3 Analysis

A molecule of NH3BH3 was optimised using the same basis set as for BH3 and NH3. Since the energies of these two reactant molecules have already been computed, using the same basis set calculations enables a direct comparison to be made to the product energy, obtaining the bond dissociation energy. As before, the optimisation was checked, and then a frequency analysis conducted to ensure that a minimum had been found.

Optimisation log file here

| summary data | convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000002 0.000015 YES

RMS Force 0.000001 0.000010 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000014 0.000060 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000007 0.000040 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-7.212973D-11

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

|

|

Frequency file: here

| summary data | low modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -5.7732 -1.9180 0.0009 0.0012 0.0015 5.5469 Low frequencies --- 263.2938 632.9747 638.4130 |

The low frequencies are within the required range, so the optimised structure energy is of high enough accuracy to be able to determine the association energy.

| wavenumber | Intensity | IR active? | type |

| 263 | 0 | no | bend |

| 633 | 14 | very slight | stretch |

| 638 | 4 | very slight | bend |

| 1069 | 41 | yes | bend |

| 1069 | 41 | yes | bend |

| 1196 | 109 | yes | bend |

| 1204 | 3 | very slight | bend |

| 1204 | 14 | very slight | bend |

| 1329 | 114 | yes | bend |

| 1676 | 28 | yes | bend |

| 1676 | 28 | yes | bend |

| 2472 | 67 | yes | stretch |

| 2532 | 231 | yes | stretch |

| 2532 | 231 | yes | stretch |

| 3464 | 3 | very slight | stretch |

| 3581 | 28 | yes | stretch |

| 3581 | 28 | yes | stretch |

| NH3 | BH3 | NH3BH3 | Dissociation Energy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy (au) | -56.55776873 | -26.6153236 | -83.22468903 | -0.0515967 |

The monomers for NH3BH3 molecule (NH3 and BH3) have previously been optimised and had a frequency analysis performed on them using the 6-31G(d,p) basis set and the B3LYP method. Since an accurate optimisation has now been made for the product, comparing the combined energies of the bond energy with the product energy allows a value to be calculated for the B-N bond in NH3BH3. Since 1 a.u. is equal to 1 Hartree, the conversion from a.u to kJ/mol can be calculated by multiplying by 2625.5.

ΔE (association energy) = E(NH3BH3)-[E(NH3)+E(BH3)] = -0.05159669 a.u. = -135.47 kJ/mol

The value found for the association energy was negative, suggesting that the formation of the ammonia borane molecule is favourable. Comparing the obtained value with literature (-274.05 kJ/mol)[3], the calculated value differs by -138.58 kJ/mol. The difference is due to the literature value considering the backbonding affect of the boron donating to the nitrogen, however this does not account for the entire difference in energy. It is likely that the accuracy of this calculation is not sufficient to model the ammonia borane complex to a high standard.

The B-N bond in the complex forms a dative covalent bond with donation from the lone pair of electrons from the Nitrogen to the empty p orbital of the Boron. Taking our calculated bond energy and comparing with previously calculated single bonds quoted in the previous bond analysis of a medium strength C-H covalent bond (432 kJ/mol)[2], the bond can be classified as a quite weak.

Project Section

Optimisation

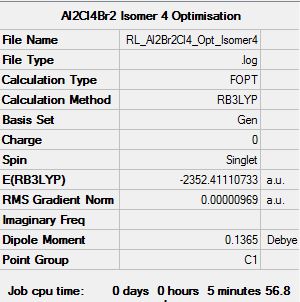

The elementd of group 3 of the periodic table only possesses 3 valence electrons, and can exist as EX3 species once bonded to three other atoms. However, these molecules only possess 6 outer electrons, therefore the extra stability associated with forming an octet is not achieved. The resulting p orbital renders these molecules highly lewis acidic, allowing these species to dimerise through bridging halogens, gaining an extra two electrons from a 3c-2e bond to fill its octet. This aim of this project is to investigate the different possible isomers of Al2Br2Cl4 with an optimisation and frequency analysis, and then to analyse the certain MO's of the lowest energy isomer.

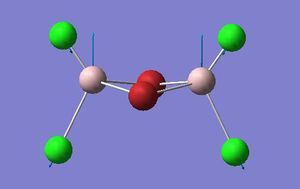

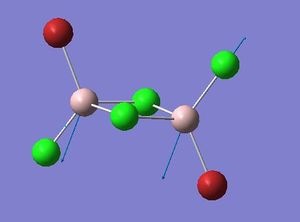

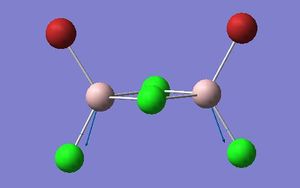

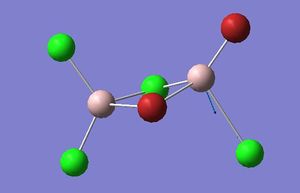

Five different isomers of Al2Br2Cl4 were optimised using a GEN basis set and the B3LYP method. Since Al and Cl have relatively few electrons, the basis set 6-31G(d,p) was used for these two atoms, whereas the LANL2DZ basis set was used for Br which contains many electrons and requires a pseudopotential to ignore the core electron contribution. In the following pictures, the Al atoms are in pink, the Cl atoms in green and the Br atoms in red. Each structure was checked for convergence and the gradient was checked the be of a sufficiently low value in the summary page.

Isomer 1

Optimisation log file here

| summary data | convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000001 0.000015 YES

RMS Force 0.000001 0.000010 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000050 0.000060 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000014 0.000040 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-5.500020D-11

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

|

|

Isomer 2

Optimisation log file here

| summary data | convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000076 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000029 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.001463 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000523 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-9.053876D-08

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

|

|

Isomer 3

Optimisation log file here

| summary data | convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000079 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000030 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.001593 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000592 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-1.040430D-07

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

|

|

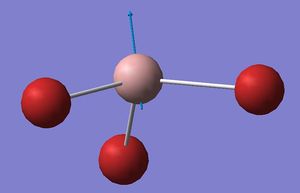

Isomer 4

Optimisation log file here

| summary data | convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000022 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000007 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000904 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000350 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-7.060377D-09

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

|

|

Isomer 5

Optimisation log file here

| summary data | convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000014 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000006 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.001591 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000723 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-1.061338D-08

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

|

|

It was noticed that isomers 4 and 5 were enantiomers (non-superposable mirror images) of each other. The energies of these two enantiomers was found to be almost identical, so subsequent calculations were only done on one of them. A possible sixth isomer containing two non-bridging bromine atoms bonded to a single Al centre was considered, but since the AlBrCl2 monomers can only have one bromine singly bonded to an aluminium, this structure is not possible. Whilst it was noticed that the point group obtained from the frequency analysis was not to the expected point group, even after numerous optimisations, the energy values obtained from fixing the point group gave almost identical energies, and hence would have similar properties for further analysis. Therefore subsequent frequency analysis was performed on these structures without restricting the point group.

Optimisation Analysis

Symmetry And Energy

| Isomer 1 | Isomer 2 | Isomer 3 | Isomer 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annotated Structure |  |

|

|

|

| Symmetry Elements | E, C2(x),C2(y),C2(z), σv(xy), σv(yz), σh(xz), i | E, C2(z), σh(xy) | E, C2(z), σv(zx), σv(zy) | E |

| Optimisation point group | C2v | CS | C2v | C1 |

| Actual point group | D2h | C2h | C2v | C1 |

| Energy (au) | -2352.4063253 | -2352.4163009 | -2352.4162783 | -2352.4111073 |

| Energy difference relative to lowest energy isomer (a.u.) | 0.0099756 | 0 | 0.0000226 | 0.0051936 |

| Energy difference relative to lowest energy isomer (kJ/mol) | 26.19 | 0 | 0.06 | 13.64 |

The lowest energy isomer was found to be isomer 2 followed by isomer 3, 4 and 1 in increasing energy. First considering the position of the bridging atoms,since Al and Cl are in the same row of the periodic table, the 3p orbitals of Al are able to favourably interact with the 3p orbitals of Cl, resulting in good orbital overlap. The 4p orbitals on Br atoms are more diffuse, and unable to overlap as favourably as Cl with the Al orbitals, therefore the energy of isomers containing bridging chlorine atoms is lower than those containing bridging Br atoms. This results in isomers 2 and 3 having a significantly lower energy than isomers 1 and 4. Comparing the two higher energy isomers, the relative energy of isomer 1 containing two bridging Br atoms (26.19 kJ/mol) is almost twice as large as isomer 4 containing a single Br atom (13.64 kJ/mol), so both Br atoms appear to equally contribute to raising the energy of the molecule.

Comparing the two lower energy isomers, isomer 2 has the Br atoms in a trans conformation, whereas isomer 3 has the two Br atoms in a cis conformation. Br is a larger atom than Cl, therefore having the two large atoms in a cis conformation causes greater steric hinderance, resulting in the slightly higher (0.06 kJ/mol) relative energy of isomer 3 compared with isomer 2.

Monomer Optimisation

In order to determine the association energy of the Al2Br2Cl4, the AlBrCl2 monomer was optimised using the same basis set and method.

Optimisation log file here

| summary data | convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000149 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000078 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000751 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000541 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-9.241379D-08

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

|

|

Frequency file: here

| summary data | low modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -0.0028 0.0023 0.0024 3.3756 3.6552 4.1209 Low frequencies --- 120.7185 133.9343 185.8750 |

| wavenumber | Intensity | IR active? | type |

| 121 | 5 | very slight | bend |

| 134 | 6 | very slight | bend |

| 186 | 33 | yes | stretch |

| 313 | 7 | very slight | stretch |

| 552 | 174 | yes | stretch |

| 614 | 186 | yes | stretch |

Association Energy

Isomer 2 was the most stable of the four isomers, so was chosen to compare to the energy of the AlBrCl2 monomer. The energies calculated from the optimised molecules can be seen in the table below.

| Energy (au) | Energy (kJ/mol) | |

|---|---|---|

| Al2Br2Cl4 | -2352.4162783 | -6176268.94 |

| AlBrCl2 monomer | -1176.1901402 | -3088087.21 |

The association energy is calculated by: ΔE = E(Isomer 2) - 2*E(Monomer) = -94.52 kJ/mol. The dissociation process therefore requires energy as the product energy is lower than the combined energy of two monomers, so the product is more stable than the monomer reactants. This result is consistent, as since the AlBrCl2 dimer only has six valence electrons, forming a dimer with 3c-2e bonds can relieve this electron deficiency to achieve a stable octet and a lower energy.

Frequency

The frequency calculations were done by taking the pre-optimised structures and changing the job type to frequency from optimization. These jobs were then run on the HPC service, and for each one the low frequencies table was analysed to check the job had been completed to sufficient accuracy and the gradient was of a low value.

Isomer 1

Isomer 1 |

Frequency file: here

| summary data | low modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -0.8120 -0.0022 -0.0018 -0.0010 0.3101 2.3644 Low frequencies --- 16.0437 63.6840 86.1925 |

| wavenumber | Intensity | IR active? | type |

| 16 | 0 | no | bend |

| 64 | 0 | no | bend |

| 86 | 0 | no | bend |

| 87 | 0 | no | bend |

| 108 | 5 | very slight | bend |

| 111 | 0 | no | bend |

| 126 | 8 | very slight | bend |

| 135 | 0 | no | bend |

| 138 | 7 | very slight | bend |

| 163 | 0 | no | bend |

| 197 | 0 | no | stretch |

| 241 | 100 | yes | stretch |

| 247 | 0 | no | stretch |

| 341 | 161 | yes | stretch |

| 468 | 346 | yes | stretch |

| 494 | 0 | no | stretch |

| 609 | 0 | no | stretch |

| 617 | 332 | yes | stretch |

Isomer 2

Isomer 2 |

Frequency file: here

| summary data | low modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -1.7424 -1.6560 -0.0006 0.0024 0.0039 2.0661 Low frequencies --- 18.2065 49.1961 72.8850 |

| wavenumber | Intensity | IR active? | type |

| 18 | 0 | no | bend |

| 49 | 0 | no | bend |

| 73 | 0 | no | bend |

| 105 | 0 | no | bend |

| 109 | 0 | no | bend |

| 117 | 9 | very slight | bend |

| 120 | 13 | very slight | bend |

| 157 | 0 | no | bend |

| 159 | 6 | very slight | bend |

| 192 | 0 | no | bend |

| 263 | 0 | no | stretch |

| 280 | 29 | yes | stretch |

| 307 | 0 | no | stretch |

| 413 | 149 | yes | stretch |

| 420 | 438 | yes | stretch |

| 459 | 0 | no | stretch |

| 575 | 0 | no | stretch |

| 580 | 316 | yes | stretch |

Isomer 3

Isomer 3 |

Frequency file: here

| summary data | low modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -1.4642 -0.4846 0.0021 0.0025 0.0033 3.1266 Low frequencies --- 17.5184 51.2019 78.5231 |

| wavenumber | Intensity | IR active? | type |

| 18 | 0 | no | bend |

| 51 | 0 | no | bend |

| 79 | 0 | no | bend |

| 99 | 0 | no | bend |

| 103 | 3 | yes | bend |

| 121 | 13 | very slight | bend |

| 123 | 6 | very slight | bend |

| 157 | 0 | no | bend |

| 158 | 5 | no | bend |

| 194 | 2 | very slight | bend |

| 263 | 0 | no | stretch |

| 279 | 26 | yes | bend |

| 308 | 2 | very slight | bend |

| 413 | 149 | yes | stretch |

| 420 | 410 | yes | stretch |

| 461 | 35 | yes | stretch |

| 570 | 33 | yes | stretch |

| 583 | 278 | yes | stretch |

Isomer 4

Isomer 4 |

Frequency file: here

| summary data | low modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -0.6750 0.0017 0.0022 0.0037 0.7835 1.6079 Low frequencies --- 16.9255 55.9184 80.0653 |

| wavenumber | Intensity | IR active? | type |

| 17 | 0 | no | bend |

| 56 | 0 | no | bend |

| 80 | 0 | no | bend |

| 92 | 1 | no | bend |

| 107 | 0 | yes | bend |

| 109 | 5 | very slight | bend |

| 121 | 8 | very slight | bend |

| 149 | 8 | very slight | bend |

| 154 | 6 | very slight | bend |

| 186 | 1 | very slight | bend |

| 211 | 21 | yes | stretch |

| 257 | 10 | yes | stretch |

| 289 | 48 | yes | stretch |

| 384 | 153 | yes | stretch |

| 424 | 275 | yes | stretch |

| 493 | 107 | yes | stretch |

| 575 | 122 | yes | stretch |

| 615 | 197 | yes | stretch |

The frequency calculations were analysed to ensure we have found a minimum for the optimisation. The first line of the low frequencies table shows that the values are within ±5cm-1, so the calculations have been completed to a high degree of accuracy. The second line in the frequency section show that all the values for each isomer are positive, confirming we have obtained a minimum energy by optimisation.

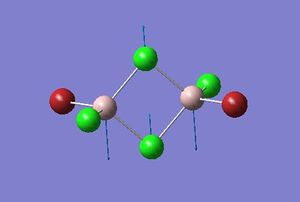

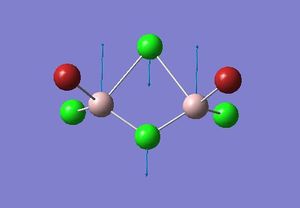

Symmetry Analysis

The symmetry of the molecule directly affects the total number of peaks observed in the IR spectrum. The requirement for a peak to be observed is for the vibration to cause a change in the dipole moment. Molecules with a low symmetry tend to have more vibrations which can result in a change of dipole moment, whereas molecules of high symmetry tend to have more symmetrical vibrations resulting in no change in dipole moment.

The number of vibrational modes in a non-linear molecule is governed by the 3N-6 rule, where N equals the number of atoms. For each Al2Br2Cl4 isomer, this corresponds to a total of 18 possible vibrational modes which should be expected to give 18 peaks in the IR spectrum. However, as previously mentioned some vibrations may be highly symmetric resulting in no change of the dipole moment, therefore no peak would be observed in the IR spectrum.

This effect can be easily seen by comparing the IR spectrum of isomers of different symmetry. The most highly symmetric Isomer 1 has D2h symmetry, and so only 7 of the 18 possible vibrations are IR active. Isomer 2 has slightly lower C2h symmetry and so is observed to have 7 peaks in the simulated IR spectrum. Whilst Isomer 3 is more highly symmetric than Isomer 2, it has a relatively large dipole moment (0.1721), therefore even slightly assymetric vibrations may cause a change in this dipole moment, resulting in 11 peaks being observed. Isomer 4 is the least symmetric (C1), and as expected has the highest number of IR active vibrations with 14 vibrations causing a change in dipole moment and observed in the IR spectrum.

| Isomer 1 | Isomer 2 |

|---|---|

|

|

| Isomer 3 | Isomer 4 |

|---|---|

|

|

Bridging And Terminal Br position frequency analysis

As previously seen with the energies of the isomers, the position of the Br atom in each isomer causes differences between them. Whether the Br is placed in a bridging or terminal position results in variations of vibrational frequencies, which can be compared by considering similar vibrations in each isomer. A comparison was first made on the nature of the bridging atoms.

| Isomer | Vibration | Frequency (cm-1) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

341 |

| 2 |  |

413 |

| 3 |  |

413 |

| 4 |  |

384 |

From the previous week one frequency analysis, the frequency value obtained from the IR spectra depends upon the square root of the spring constant for the bond divided by its reduced mass. Therefore the highest frequency bands will result from a combination of the highest spring constant and lowest reduced mass. Considering firstly the reduced mass of the bridging atoms, Cl is one row above Br and has a lower mass, and so the combination of two Cl atoms will result in the lowest reduced mass for Al-Cl. The spring constant can be approximated as the bond strength, so is proportional to the bond enthalpy; therefore the largest bond enthalpy will give the highest value for k. The Al-Cl and Al-Br bond enthalpies are 502 kJmol-1 and 429.2 kJmol-1 respectively [4], therefore it is expected that Al-Cl bond will have the largest force constant. These Al-Cl bonds are stronger as expected, since Al and Cl are the in the same row the orbital overlap is much better than with diffuse Br orbitals.

Considering isomers 2 and 3, when both the bridging atoms are Cl the frequency is 413 cm-1, which are the highest values observed. This is regardless if the Br atoms are cis or trans to each other, which is expected as only the bridging bond frequencies are being considered and is essentially independent of the nature of the terminal atoms. For isomer 1, the opposite is true as since the Al-Br spring constant is small and the Al-Br reduced mass relatively large, this gives the lowest frequency value of 341 cm-1. In the intermediate case when one bridging atom is Br and the other Cl for isomer 4, the frequency is seen to be between the highest and lowest values at 384 cm-1.

It can be concluded that the Al-Br stretching frequency is weaker than the Al-Cl stretching frequency. By examining the stretching of the bridging bonds, the value of frequency was much lower when these comprised of Br atoms rather than Cl atoms. These bridging bonds are the bonds broken in dissociation, so their relative strength can be used as a judge of how stable the isomer is. Since the frequency is associated with bond strength and therefore energy, this frequency analysis confirms our results for optimisation. Isomer 2 and 3 have the highest frequency value and strongest bridging bond, therefore are the most stable and of the lowest energy, whereas isomer 1 which has the lowest frequency and has the weakest bridging bonds is also found to be the least stable of all the isomers in agreement with the previous optimisation.

The next frequency comparison made was by changing the terminal atoms and observing the variation in frequency for the same vibrational mode in the isomers.

| Isomer | Vibration Image | Frequency (cm-1) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

617 |

| 2 |  |

580 |

| 3 |  |

583 |

| 4 |  |

614 |

The Br atoms were found to stretch only very slightly in vibrational modes analysed, which is as expected due to its much larger mass compared to Cl. Consistent with the same theory as before, the isomer with all Cl atoms occupying the terminal positions gave the highest frequency value, which was observed to be 617 cm-1. Isomers 2 and 3 were relatively similar in frequency at 580 cm-1 and 583 cm-1, as they contain equal numbers of Cl atoms in the terminal positions. There are two fewer Br atoms in the terminal positions than Cl in this case, therefore the frequency is less than Isomer 1 due to the higher reduced mass of the Al-Br bond and lower spring constant. Isomer 4 contains 3 Cl atoms in terminal positions and has a frequency value lower than that of isomer 1 with 4 terminal Cl atoms, and higher than that of 2 and 3 with 2 terminal Cl atoms. The same frequency trend is observed, of the Al-Br stretch being weaker than the Al-Cl stretch.

MO Analysis

An MO calculation was carried out on the lowest energy isomer, which was previously determined to be isomer 2. An energy analysis was performed on the optimised structure of isomer 2, followed by modelling and viewing all occupied orbitals. Orbitals below level 30 are all considered as core orbitals; their energy is so low that their effects on the valence orbitals is not significant so they are not included in this analysis.

| summary data | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

MO 31

MO 31 was identified as the first of the 'non-core' orbitals, which are ones too deep in energy and contain very small contributions to the chemical properties. No nodes were observed in the MO, which contained a very high degree of delocalisation spread across the bridge from the same phase Cl s orbitals. The MO is considered to be strongly bonding, due to the interactions were identified below.

1. Strongly bonding through space interaction between the s orbitals of both bridging chlorines. The orbital has its electron density delocalised over the bridging atoms, with no nodes.

2. Weak through space bonding interaction between the orbitals on the terminal Cl atoms and the delocalised bridging orbital.

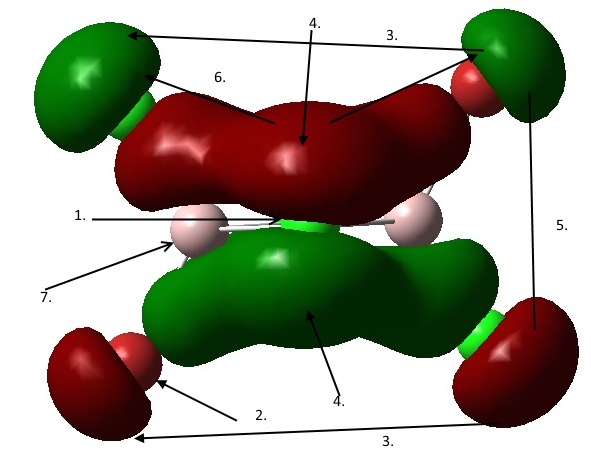

MO 40

This MO was considered to be quite strongly bonding after a consideration of the orbital interactions. A nodal plane was observed intersecting the Al and Cl atoms, along with 4 nodes on each of the terminal Br/Cl atoms. The MO is observed to be highly delocalised, with a π type interaction observed across the entire bridge and onto one lobe of each of the terminal atoms, due to same phase interactions between the p orbitals.

1. Nodal plane through the bridging atoms of the molecule. As the nodal plane passes through each atom, the orbitals contributing to the bridging orbitals are identified as p orbitals.

2. Node found at each terminal atom, indicating p-orbital contribution.

3. Weak through space bonding interaction between a terminal Br p orbital and a terminal Cl p orbital.

4. Strong through space π bonding interaction from the same phase overlap of the bridging Cl p orbitals and terminal Br/Cl p orbital.

5. Medium through space antibonding interaction between the p orbitals of Cl and Br atoms.

6. Medium through space antibonding interaction between the opposite phase p orbital of the terminal atom, and the p orbital of the bridging Cl atoms.

7. Al atoms with no contribution to MO.

MO 52

This MO is found to be close to the HOMO (MO 54), and is therefore found to be one of the weakly bonding MO's by analysing the bonding and antibonding interactions. Two nodal planes were observed with one passing through the Al atoms, and the other passing through the node of the bridging Cl atoms. 6 nodes were present, one on each bridging and terminal Br/Cl atom. All of the interactions in the MO involve p-orbitals from the Cl/Br atoms, with very little delocalisation of the MO across the molecule and the p-orbitals remaining discrete. The bonding/antibonding character of the MO is quite similar, making a qualitative judgement of the bonding character of the MO is difficult. Considering the relative energy of the occupied MO (-0.32052), the bonding effect is slightly stronger than the antibonding character so the MO was determined to be weakly bonding.

1. + 2. Nodal plane passing through the bridging atoms of the molecule, therefore identifying the bridging atoms as p orbitals. Node found at each bridging and terminal atom, indicating presence of p orbitals.

3. Medium through space antibonding interaction between a bridging Cl p orbital and a terminal Br p orbital.

4. Weak through space antibonding interaction between terminal Br p orbitals, in which the Br atoms are bonded to different Al atoms.

5. Medium through space bonding interaction between bridging and terminal Cl p orbitals.

6. Medium through space antibonding interaction between terminal Cl and Br p orbitals.

7. Weak through space bonding interaction between the terminal Cl and Br p orbitals, bonded to different Al atoms.

8. Medium through space antibonding interaction between the two bridging Cl p orbitals.

MO 56

MO 56 was found to be one energy level above the LUMO. A nodal plane was observed through the middle of the bridging Cl atoms, with 6 nodes found, one at each terminal and bridging Br/Cl atom. The Al s orbitals and Br/Cl p orbitals remainied discrete, with very little delocalisation of the MO across the molecule. The unoccupied MO was found to be weakly antibonding, due mainly to strong through bond antibonding interactions between the Al s orbital and bridging/terminal Cl/Br orbitals.

1. Nodal plane through the bridging Cl atoms of the molecule, through the node of the p orbitals

2. Node found at each terminal and bridging Br/Cl atom in the middle of each p orbital. Al contribution involves its s orbital so no node found for either atom.

3. Strong through bond antibonding interaction between the opposite phase Al s orbital and terminal Br/Cl p orbital

4. Medium through space bonding interaction from the same phase overlap of the bridging Cl p orbitals.

5. Strong through bond antibonding interaction between the p orbitals of the bridging Cl atom and opposite phase Al s orbital.

6. Medium through space bonding interaction between the same phase p orbital lobe of the terminal Cl/Br atom with the other terminal p orbital of the terminal Cl/Br atom.

7. Weak through space antibonding interaction of the terminal p orbitals of the Br/Cl atoms.

MO 60

MO 60 was chosen as the highest energy orbital in this discussion. A nodal plane was found parallel to the Al and terminal Br/Cl atoms, and one was found bisecting the middle of the bridging Cl atoms. 8 nodes were found, with one on every atom in the molecule. The degree of delocalisation of the MO across the molecule is very low, with very distinct p orbitals being viewed on each Al/Cl/Br atom. Numerous strong through bond antibonding interactions can be seen between the bridging and terminal Br/Cl atoms with the central Al atoms, resulting in an overall strongly antibonding MO.

1. Nodal plane passing through central Al atoms, through the node of the Al p orbitals and terminal Cl/Br orbitals.

2. Node found at each atom in the molecule indicating that p orbitals are contributing from each atom.

3. Strong through bond antibonding interaction between the opposite phase Al p orbital and terminal Br/Cl p orbital

4. Medium through space bonding interaction from the same phase overlap of the terminal Cl/Br p orbital, and the bridging Cl p orbital.

5. Strong through bond antibonding interaction between the p orbitals of the bridging Cl p orbital and opposite phase Al p orbital.

6. Medium through space antibonding interaction between opposite phase p orbital lobes of the terminal Cl with the other terminal Br.

7. Strong through space antibonding interaction of the opposite phase Al p orbitals.

8. Medium through space bonding interaction between the p orbitals of the terminal Cl and Br atom bonded to the same Al atom.

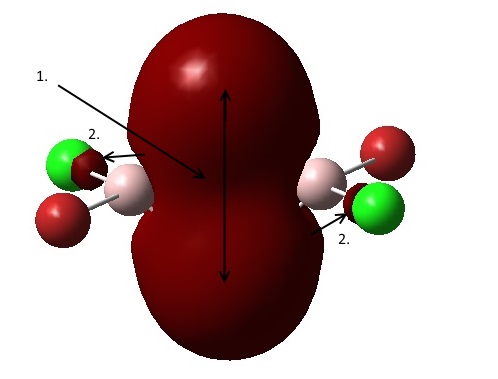

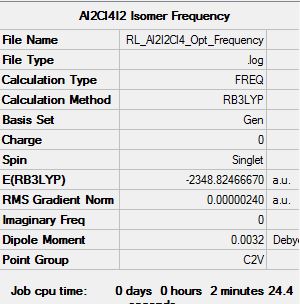

Al2I2Cl4

Since the isomers of the Al2Br2Cl4 molecule have been optimised and a frequency analysis conducted on them, a further analysis was conducted by changing the Br atoms for even heavier I atoms. The isomer chosen was the one with both bridging positions occupied by I atoms. The same basis set and method were used (B3LYP on Al and Cl, LANL2DZ on Br, GEN method) to allow for a comparison to be made between optimisation and frequency analysis of the same isomer for Al2I2Cl4.

Optimisation log file here

| summary data | convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000004 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000002 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.001276 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000577 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-3.801440D-09

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

|

|

Frequency file: here

| summary data | low modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -0.0031 -0.0029 -0.0017 0.6229 1.2924 1.6116 Low frequencies --- 11.6809 65.2884 76.7974 |

Energy Comparison

| Energy (au) | Energy (kJ/mol) | |

|---|---|---|

| Al2Br2Cl4 | -2352.4063253 | -6176242.81 |

| Al2I2Cl4 | -2348.8246667 | -6166839.16 |

The difference in energy between the two complexes is calculated to be 9403.65 kJ/mol in favour of the Al2Br2Cl4 molecule. Since I is even lower down than Br in group 17, the 5p orbitals of Iodine overlap even more poorly than the Br p orbitals with the Al 3p orbitals. Therefore, the bridging iodine bonds are weaker resulting in the energy of the Al2I2Cl4 molecule being much higher than that of the chlorine bridged complex.

Frequency Comparison

| Molecule | Vibration | Frequency (cm-1) |

|---|---|---|

| Al2I2Cl4 |  |

313 |

| Al2Br2Cl4 |  |

341 |

I is one below Br in group 17, it has a much larger mass and therefore the reduced mass of the Al-I system will be larger than for Al-Br. The bond enthalpy of Al-I is 369.9, compared to 429.2 kJ/mol for Al-Br[4]. As bond enthalpy is proportional to the bond strength and hence spring constant k, Al-I has a lower k value than Al-Br. This can also be rationalised by the fact that I 5p orbitals form a weaker overlap with the Al 3p orbitals, whereas Br 4p orbitals have a more favourable overlap and hence a stronger bond is formed. The frequency value obtained from the IR spectra depends upon the square root of the spring constant for the bond divided by its reduced mass. Since Al-I has a higher reduced mass and lower spring constant than Al-Br, the frequency observed is smaller for the former. The values of frequency can also be placed in the context of energy: since the frequency values are lower for Al2I2Cl4, this molecule is more unstable than Al2Br2Cl4 which matches with the optimisation calculation.

By doing a simple optimisation and frequency calculation for this Al2I2Cl4 molecule, the energy can be compared to similar molecules and a more thorough comparison of the effect of the bridging atoms can be presented.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, W. M. Haynes, D. R. Lide and T. J. Bruno, CRC Press, Boca Raton, 93rd edn., 2012.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Shriver, Atkins, Inorganic Chemistry, Oxford University, 5th Edition, 2010

- ↑ Mitoraj, M. P., J. Phys. Chem., 2011, 115, 14708-14716.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Luo, Y. R. Comprehensive Handbook of Chemical Bond Energies, CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, 2007