Rep:Mod:RG1712

The Free Energy and Thermal Expansion of MgO

Introduction

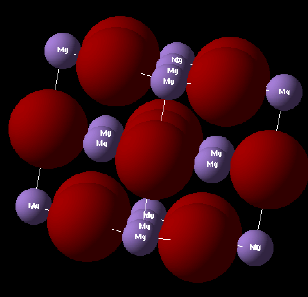

MgO, occurring naturally as periclase, is an ionically bonded lattice of Mg2+ and O2- ions. It adopts the rock-salt (B1) structure with a primitive rhombohedral unit cell and is recognised for the fact that it is one of the least polymorphic solids known 1. In this experiment molecular simulations are utilised as a means of determining the thermodynamic properties of an MgO crystal. One key aspect of the use of simulations is that, if deemed to be reliable, they possess the scope to provide estimates of material properties that may not be obtained by conventional experiments. Periclase, as one of the most abundant minerals on the planet, has found use in a number of applications including cement manufacture, desiccation and as an insulator in industrial cables. Periclase is also an important constituent mineral phase of the Earth's mantle 2. In light of this one may begin to appreciate the role of simulations not only in gathering information about materials that may prove valuable to industry but also in enhancing our knowledge of the planet. Though it may not be possible to reproduce the high pressures and temperatures of the Earth's mantle in the lab, such feats may be accomplished through simulation.

The thermal expansion coefficient or thermal expansivity of MgO is computed using the simulation methods of lattice dynamics (LD) and molecular dynamics (MD) respectively. Lattice dynamics operating within the quasi-harmonic approximation (QHA) applies the harmonic approximation of interatomic forces to the system for each value of the lattice constant and in so doing accounts for volume dependent thermal effects. Molecular dynamics on the other hand performs a classical simulation featuring forces derived from the chosen potential function. In this manner anharmonic effects may be taken into account. The results obtained via the two methods are compared against experimental literature values in order to evaluate their efficacy within different temperature ranges. In the case of LD preliminary calculations of the phonon density of states (DOS), phonon dispersion and free energy were carried out in order to determine the optimal k-point grid size that would be required for the subsequent thermal expansion computation.

GULP (General Utility Lattice Program) was the simulations code used to perform the calculations alongside the DLVisualize graphical user interface. GULP is a versatile program with which it is possible to model two-dimensional surfaces, gas phase clusters and, as is the case with this experiment, three-dimensional periodic solids. In order to acquire information about the lattice energetics of MgO it is necessary to consider all species within the crystal. In practice this is achieved by separating out components of the lattice energy into long and short-range potentials. The dominant long-range potential term is generally the electrostatic energy in the case of oxides. The Ewald summation, as noted by Gale 3, is the most efficient method of computing this term for small systems and so is used for this study. Likewise, the Buckingham potential is the short-range potential of choice for this experiment due to its extensive use in modeling ionic materials. The functional form of the Buckingham potential is given below:

Where A is the coefficient of the repulsive exponential term, C is the coefficient of the attractive dispersion term and r is the distance between two atoms 3. Working in conjunction with each other these two terms account for a simple picture of the interactions between species pairs.

Results and Discussion

An Initial Calculation on MgO

Lattice energies are indicative of the strength of the ionic bonding in a crystal. As a positive quantity the lattice energy may be described as the energy given out when oppositely charged, gas phase ions form a solid. Conversely, as a negative quantity the lattice energy may be viewed as the binding energy of the crystal. The latter is computed here.

| 0 | 2.10597 | 2.10597 |

| 2.10597 | 0 | 2.10597 |

| 2.10597 | 2.10597 | 0 |

| a = 2.9783 | alpha = 60.0000 |

| b = 2.9873 | beta = 60.0000 |

| c = 2.9783 | gamma = 60.0000 |

| Interatomic Potentials | 6.712 eV |

| Monopole-monopole(real) | -5.1159 eV |

| Monopole-monopole(recip) | -42.6806 eV |

| Monopole-monopole(total) | -47.7965 eV |

| Total Lattice Energy | -41.0753 eV |

| Total Lattice Energy | -3963.1403 kJ/(mole of unit cells) |

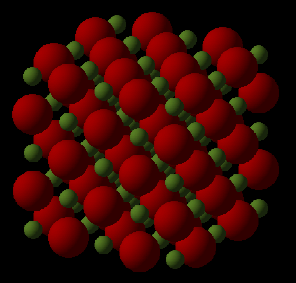

Tables 1-3 summarise the information obtained on performing a GULP single point calculation. The cartesian lattice vectors describe the MgO unit cell and combine to form the rhombohedral primitive cell of MgO. The features of the primitive cell are listed in table 2 under cell parameters. In spite of the fact that the primitive cell is the smallest periodic unit of the MgO crystal it is more often the case that the conventional cell is used to perform calculations. Although larger, the conventional cell is cubic and thus acts as a better representation of the symmetry of the MgO crystal. The conventional cell is larger in volume relative to the primitive cell by a factor of 4. Graphics of the primitive and conventional cells may be viewed below in figures 1 and 2 respectively.

The Phonon Modes of MgO

The overall aim of the experiment is to compare the performance of LD against that of MD in predicting accurately the thermal expansion of MgO. LD relies on the successive implementation of the harmonic approximation for increasing values of the lattice constant as the solid expands. As such, in order to have confidence in the values of the parameters predicted by LD it is first necessary to compute an accurate phonon density of states to be used in the subsequent thermal expansion calculations. This will be accomplished through striking a balance between finding a k-point grid size capable of producing a relatively precise density of states whilst keeping CPU running time down to an acceptable level. The phonon dispersion curves of MgO will also be examined here.

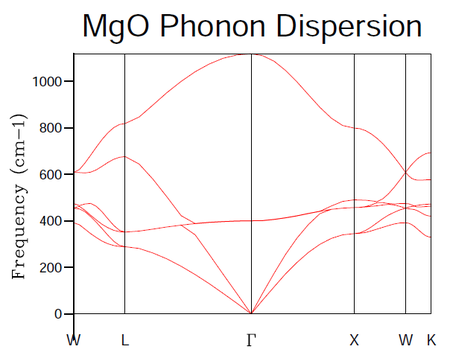

The phonon dispersion curves were computed at 50 points along the path W-L-G-W-X-K. These letters denote directions of high symmetry that are specific to the first Brillouin zone of the fcc lattice. The results of the calculation are given below in figure 3.

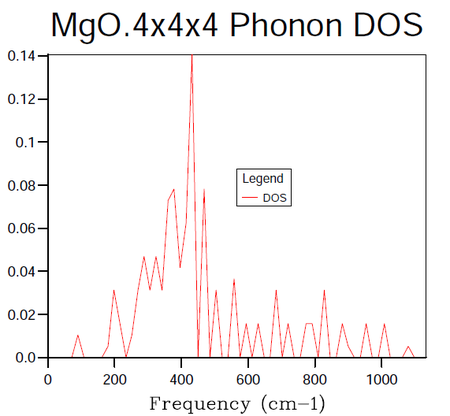

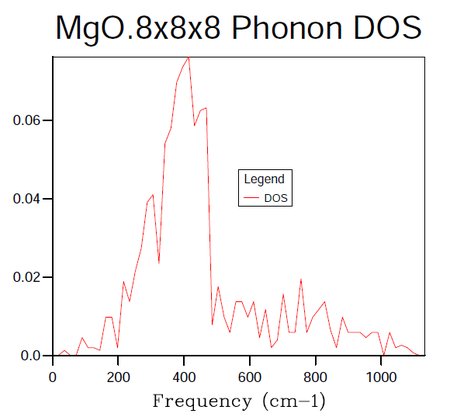

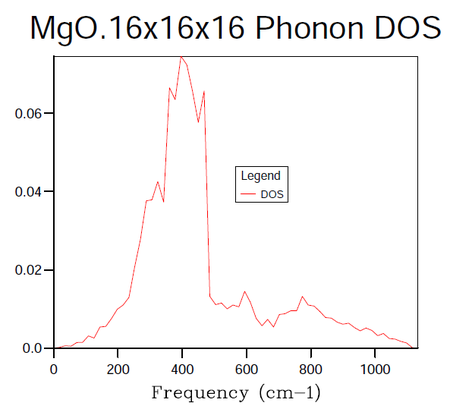

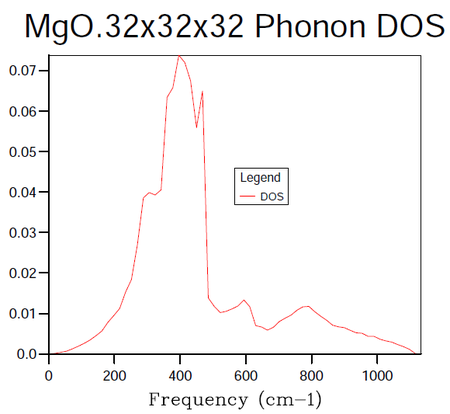

In order to identify the bulk material properties of a system, rather than thinking about the individual vibrational modes presented by the phonon dispersion curves it is helpful to group modes of similar energy together. This is the premise of the DOS, it provides the number of vibrational modes at a particular energy per unit volume. This follows from the energy-frequency relation derived by treating the phonons as quantum oscillators, E = hω, where h is Planck's constant and ω is the frequency in units of cm -1. Once the vibrational energy levels of the MgO crystal are known it will become possible to gain access to information pertaining to the macroscopic characteristics of the system. States are labelled by their k-points and so by summing over them it is possible to compute the DOS for a given sample of k-points. In the following calculations the grid size method proposed by Monkhorst 4 was used. The resulting DOS plots for varying grid sizes are displayed in figures 4-9.

| k-point Grid Size | F(kJmol-1) | ΔF(kJmol-1) | F(eV) | ΔF(eV) | Absolute ΔF(eV) from 32 Grid | CPU time (seconds) | Peak Dynamic Memory (Megabytes) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1x1x1 | -3949.1480 | 3.5620E-01 | -40.9303 | 3.6920E-03 | 3.818E-03 | 0.0025 | 0.48 |

| 2x2x2 | -3948.7918 | 1.7087E-02 | -40.9266 | 1.7700E-04 | 1.2600E-04 | 0.0033 | 0.51 |

| 3x3x3 | -3948.7747 | 1.5400E-02 | -40.9264 | -1.8000E-05 | 5.1000E-05 | 0.0077 | 0.53 |

| 4x4x4 | -3948.7764 | -2.7000E-03 | -40.9265 | -2.8000E-05 | 3.3000E-05 | 0.0106 | 0.58 |

| 8x8x8 | -3948.7791 | -5.0000E-04 | -40.9265 | -4.0000E-06 | 5.0000E-06 | 0.0852 | 1.13 |

| 16x16x16 | -3948.7796 | 0.0000E+00 | -40.9265 | -1.0000E-06 | 1.0000E-06 | 0.7639 | 5.62 |

| 32x32z32 | -3948.7796 | - | -40.9265 | - | - | 11.5350 | 41.52 |

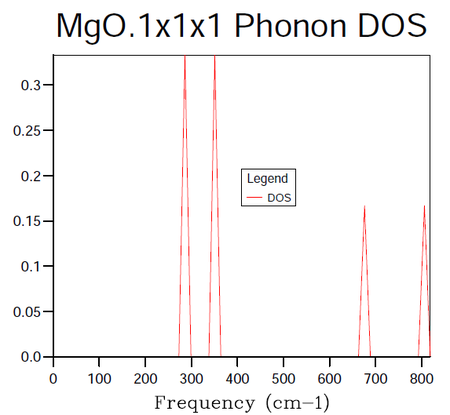

One may observe in figure 4 above the results of taking the DOS from a sample consisting of a single k-point. The dimensions 1x1x1 refer to the shrinking factors in the A, B and C directions. The coordinates retrieved from the log file for this particular k-point correspond to half the length of the sample grid in each direction i.e. (0.5, 0.5, 0.5) in real space and (π/a, π/a, π/a) in reciprocal space. This is known to be the symmetry point L of the first Brillouin zone of the fcc lattice. The frequencies in the DOS log file for the 1x1x1 grid correspond to 286, 351, 676 and 806 cm -1 respectively. This information is displayed graphically in figure 4. Armed with this information, one can now examine figure 3 and note that the vertical line belonging to the L symmetry point crosses the dispersions curves at values of the frequency corresponding to those observed in the DOS plot. Thus, further evidence has been provided to support the notion that the k-point chosen for the calculation is coincident with the symmetry point L.

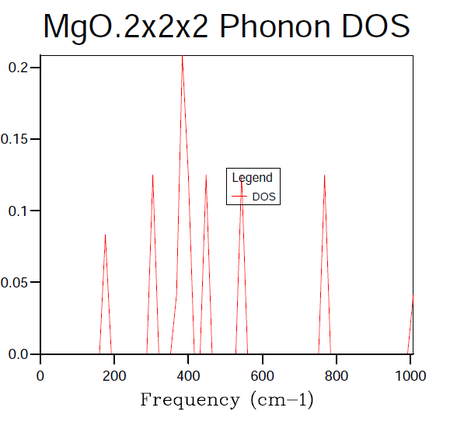

As progressively larger grid sizes are sampled, the density of states plot starts to resemble a smooth continuum of frequencies as opposed to a set of discrete vibrational modes. This stems from the fact that more sample points are being considered and therefore a better averaging process is achieved. If one were to take the grid to infinitely large dimensions, a perfect representation of the DOS would be obtained. The computational cost incurred by such an approach however would make it unfeasible. The fact that progressively larger grid sizes going from even to odd dimensions or vice versa do not show monotonic behaviour in their convergence is worthy to note at this stage. There are even certain cases where the number of k-points sampled can decrease going from for example 8x8x8 to 9x9x9 5. In this instance the number of points sampled hinges on whether or not the origin gamma is included in the grid (mesh) used. A further factor to consider when choosing a grid size is whether the parity of the chosen grid, odd or even will affect the symmetry of the lattice.

In the attempts to find the right balance between accuracy and computational expense the grid size was doubled for each subsequent calculation. In this manner it was ensured that the same k-points as had been sampled in previous runs would be taken again in addition to new k-points. It should be noted in table 4 above that the 3x3x3 grid was run for the sake of obtaining a value of the Helmholtz free energy at this grid size and not the DOS. The dimensions of 16x16x16 were decided upon as the minimum grid size required for a good DOS approximation following a visual inspection of the plots. The contrast in the smoothness of the distribution shown in figure 8 is negligible when compared to figure 9 (figures 8 and 9 representing the grid sizes of dimension 16x16x16 and 32x32x32 respectively). On the other hand, looking at the data in table 4 one may see a distinct difference in the CPU time required to produce the two DOS plots with the overheads of figure 9's CPU usage being larger by a factor of approximately 15. The peak dynamic memory usage required for the 32x32x32 grid size is a factor of roughly 9 larger than the corresponding memory for the 16x16x16 grid. Although the 8x8x8 grid utilises a smaller CPU time and a smaller peak dynamic memory usage relative to the 16x16x16 grid (factors of 9 and 5 when the two quantities are compared), the averaging in the DOS does not seem to be of high enough quality to avoid significant errors in the results produced from the thermal expansion calculations to follow.

Mathematically the DOS may be related to the dispersion of a crystal such as MgO in the one-dimensional case by thinking about the number of k-points in a given dω (change in frequency) and in a given dk in the phonon dispersion diagram. The number of modes in dk is equal will be equal to dk divided by the point-spacing 2π/λ. Taking into account the fact that there are positive and negative vectors in the dispersion curve diagram the number of k-points in a region dk may be given by (L/π)dk as 2π/L is the distance between k-points in a chain of atoms of length L. When one invokes that the corresponding points in the interval dω are DOS(ω)dω one can equate the numbers within each region i.e. (L/π)dk = DOS(ω)dω and after some manipulation solve for the DOS. One interesting intermediate in this derivation of the DOS as a function of ω is the equation (L/π)dω/(dω/dk) = DOS(ω)dω which shows that the DOS is inversely proportional to the gradient of the dispersion curve. One can see this relationship manifest itself by comparing figures 3 and 4 above. The peaks in frequency in the 1x1x1 DOS plot correspond to regions of the dispersion curve where the bands are very flat i.e. have close to zero gradient. As such, the greatest number of states will be found at flat regions of the dispersion diagram.

The optimal grid size for MgO may be qualitatively discussed in reference to other structures. These structures include similar oxides such as CaO, zeolites such as the silicate mineral faujasite and metals such as Li. Generally the k-points needed for a calculation on a structure with low energy dispersion is correspondingly low. The key aspect involved in the comparison of these structures is that larger unit cells in real space correspond to smaller cells in reciprocal space. Consequently for larger real space unit cells, the apparent density of a k-space grid will increase manifold relative to a small unit cell. In discussing the applicability of using the optimal grid size for MgO in a calculation featuring CaO one could argue that a similarly sized grid should be used for both. Although CaO will have a slightly larger unit cell the difference in size would not be enough to alter the density of points in k-space significantly. Faujasite on the other hand has a very large unit cell counting in the hundreds of atoms. The optimal grid size for MgO would be unnecessarily large when used in a study involving faujasite. Instead a smaller grid size would produce a similar density in k-space. In metals such as Li the Fermi surface and its associated sensitivity must be taken into account. One is likely to come across discontinuities in k-space and so one must take great care when integrating over the k-points chosen. In light of this factor a denser, higher dimension, k-point grid should be used relative to MgO. One possible result of failing to use a dense enough grid would be the appearance of unphysical acoustic branches near the origin of the dispersion curve diagram 6. Electron-phonon interactions in metals lead to fluctuations in the charge density of the system. This occurs by virtue of the fact that that the phonons are positively charged and interact with the Fermi electron gas. This leads to distortion of the dispersion bands near the Fermi energy of the metal. In the broadest sense a large number of k-points are needed to produce accurate results for distorted (i.e. not flat) dispersion bands whereas only a relatively small number of k-points are acquired for insulators such as MgO which have flat dispersion bands.

Calculating the Free Energy - The Quasi-Harmonic Approximation

The free energy was calculated for successively larger grid sizes starting with 1x1x1. The results of the calculations are summarised in table 4 above. It is important to realise that the energy will not converge monotonically when one steps from an even to an odd dimensioned grid. Instead, as has been observed on going from the 2x2x2 grid to the 3x3x3 grid and subsequently to the 4x4x4 grid the values of the free energy given by the calculation oscillate around the value of the most accurate estimate (the 32x32x32 grid). In contrast to the determination of a suitable grid size for the DOS calculation, an optimal grid size is selected in the free energy calculation based on numerical data. Hence, one may now select the margin of error in the value of the free energy that is tolerable and tune the k-point grid size accordingly. Two methods for determining the accuracy of a grid size to a certain error bound value were chosen. In the first method the absolute differences were taken between the energy produced from the grid size being observed and the 32x32x32 grid reference. In the second method the difference was taken between successively larger grid sizes. A list of error bound values and suggested grid sizes is given in table 5.

| Error Bound (meV) | Grid Size |

|---|---|

| 1 | 2x2x2 |

| 0.5 | 2x2x2 |

| 0.1 | 3x3x3 |

As may be seen from the data in table 4 the 2x2x2 grid has an error bound of 1.7700E-04 eV, the larger of the bounds given by the two methods mentioned above. As the values of 1 and 0.5 meV are larger than this bound one may say with some confidence that the 2x2x2 grid would be suitable in these cases. The value of 0.1 meV requires a higher degree of tolerance than the 2x2x2 grid can supply and therefore the 3x3x3 grid, which has a maximum tolerance of 5.1000E-05 eV should be used. The worst-case scenario tolerance is taken. Once again the 16x16x16 k-point grid would seem to represent the best balance of accuracy and CPU time. It should be mentioned that this technique of honing in on the grid size at which there is no change in the energy calculated could be described as a convergence test. Indeed it is likely that some structures will converge to accurate values faster i.e. for a smaller grid size than others. In the case of a similar oxide to MgO such as CaO the convergence limit is likely to be similar and so it would be sensible to use an identical grid size.

The Thermal Expansion of MgO - Lattice Dynamics

By optimising the structure of MgO with respect to the free energy at a given temperature and pressure it is possible to identify the structure that will be adopted under the chosen conditions and hence simulate thermal expansion. The optimisation is performed here within the quantum harmonic approximation. The distinction between the harmonic approximation (HA) and the quantum harmonic approximation (QHA) is that in HA the reference structure used is the mechanical equilibrium structure whereas in the QHA it is the thermodynamic equilibrium structure at a given temperature and pressure 7. As the pressure is kept constant in this simulation the change in structure (volume expansion) may be monitored as a function of temperature. The plots of the Gibbs free energy and the lattice constant against temperature are located below.

On examining the plot of the Gibbs free energy against temperature in figure 10 one may observe a decrease in free energy with increasing temperature. This behaviour is expected from the equation (dG/dT) = -S where dG and dT are the partial derivatives of the Gibbs energy and the temperature at constant pressure. S denotes the entropy. A second equation useful when examining this plot is the definition of the Gibbs energy in terms of the enthalpy and entropy of a system, G = H - TS where H represents the enthalpy. The negative sign in the second equation implies that the Gibbs energy will be more negative at higher temperatures which is supported by the plot. One may note also that the entropy in this equation is weighted by the temperature. Linking this fact back to the first equation one finds that as the entropy becomes larger at higher temperatures so too does the gradient of the Gibbs energy as a function of temperature.

The plot of the primitive cell lattice constant as a function of temperature in figure 11 shows that the cell dimensions are increasing as the temperature is raised. The origin of this behaviour lies in the fact that at higher temperatures the average amplitude of vibrations will increase. As a result the net average atom-to-atom distance will increase accordingly and as the cell constant is defined by the positions of the atoms it stands to reason that this parameter will grow larger too. Hence thermal expansion is exhibited.

The thermal expansion coefficient α is related to the volume of the cell by the equation, α = 1/V0*(dV/dT), where V0 is the initial volume of the cell before the temperature has been increased and dV/dT is the partial rate of change of the volume of the cell with respect to temperature at constant pressure. Figures 12 and 13 feature plots of cell volume against temperature and so α may be computed from the equations of the respective slopes. The data from both plots is tabulated in tables 6 and 7 with a literature comparison included in table 7 8.

| Initial Cell Volume(Å^3) | Gradient(Å^3/K) | α(K^-1) |

|---|---|---|

| 18.8900 | 5E-04 | 2.6459E-05 |

| Initial Cell Volume(Å^3) | Temperature(K) | α(K^-1)- Calculated | α(K^-1)-Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18.8383 | 100 | 2.4000E-04 | - |

| - | 200 | 2.8000E-04 | - |

| - | 300 | 3.2000E-04 | 3.12E-05 |

| - | 400 | 3.6000E-04 | 3.57E-05 |

| - | 500 | 4.0000E-04 | 3.84E-05 |

| - | 600 | 4.4000E-04 | 4.02E-05 |

| - | 700 | 4.8000E-04 | 4.14E-05 |

| - | 800 | 5.2000E-04 | 4.26E-04 |

| - | 900 | 5.6000E-04 | 4.38E-04 |

| - | 1000 | 6.0000E-04 | 4.47E-04 |

Quite surprisingly from the calculations it may be seen that the linear plot, truncated form 300 K onwards, better matches the literature values of the expansion coefficient. the approach taken with the equation of the trendline in figure 12 was to differentiate it in order to calculate the gradient at specific temperatures. The fit was quadratic and so a better approximation could have been made by fitting a higher order polynomial trendline. The approximation made in fitting a linear trendline to the data is that the expansion coefficient is independent of temperature. The fact that such a rough approximation still produces a result that is on the same order of magnitude as the literature values can provide some level of confidence in the data acquired through the simulation. Data was rounded to 4 decimal places for clarity.

The physical origin of thermal expansion as mentioned briefly above and arises from the increasing amplitude of atomic vibrations at higher temperatures. Higher amplitude oscillations mean a higher average internuclear distance between atoms in a cell, inducing expansion. As the temperature approaches the melting point of MgO, phonon-phonon interactions become more abundant by virtue of the fact that the thermal phonon population increases. The implication of these interactions is that phonons of a particular state decay into different phonons. Within the harmonic approximation and by extension the quasi-harmonic approximation phonons are assumed to be non-interacting. Hence at progressively higher temperatures the quasi-harmonic approximation becomes more and more likely to neglect these effects and so the simulated modes become less representative of the actual modes.

The fundamental difference between the harmonic and the quasi-harmonic approximations is that the latter allows for the bond length to increase with temperature, albeit in a slightly artificial manner. The harmonic potential is a symmetric potential and so the average value of the interatomic distance does not change. In order to represent the classical effect of thermal expansion, an anharmonic potential is required in order to describe the system. In the quasi-harmonic approximation, a harmonic potential is applied for each individual value of the lattice constant and the MgO crystal is allowed to expand in this fashion.

The Thermal Expansion of MgO - Molecular Dynamics

Computing the thermal expansion of MgO using molecular dynamics (MD) requires the use of a supercell in place of the primitive cell that was used for LD calculations. The 32 MgO unit or equivalently 64 atom supercell was used as can be seen in figure 14. A larger supercell would yield more accurate results from the MD method but would incur overheads in CPU time. The supercell can be constructed by taking a conventional cell (4 MgO units) as in figure 2 and repeating it twice along each cell vector.

An NPT ensemble was used for the purposes of monitoring the thermal expansion with a time step of 1 femtosecond. The number of equilibration and production steps were set to 500 and the number of sampling and trajectory write steps were set to 5. The temperature was varied to the limit at which MgO begins to melt at around 3000K. One can find the thermal expansion data for the LD and MD computations in table 8.

| Temperature | LD-Primitive Cell Volume/Cell Volume per Formula Unit (Å^3) | MD-Supercell Volume (Å^3) | MD-Conventional Cell Volume (Å^3) | MD-Cell Volume per Formula Unit (Å^3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 18.8383 | 599.5133 | 74.9392 | 18.7348 |

| 200 | 18.8562 | 600.5276 | 75.0660 | 18.7665 |

| 300 | 18.8900 | 602.4240 | 75.3030 | 18.8258 |

| 400 | 18.9325 | 604.2332 | 75.5292 | 18.8823 |

| 500 | 18.9801 | 606.1516 | 75.7690 | 18.9422 |

| 600 | 19.0312 | 608.4364 | 76.0546 | 19.0136 |

| 700 | 19.0851 | 610.2139 | 76.2767 | 19.0692 |

| 800 | 19.1413 | 611.8453 | 76.4807 | 19.1202 |

| 900 | 19.1996 | 613.1367 | 76.6421 | 19.1605 |

| 1000 | 19.2600 | 614.8619 | 76.8577 | 19.2144 |

| 1100 | 19.3225 | 616.4710 | 77.0589 | 19.2647 |

| 1200 | 19.3872 | 618.7923 | 77.3490 | 19.3373 |

| 1300 | 19.4541 | 620.6901 | 77.5863 | 19.3966 |

| 1400 | 19.5233 | 622.9400 | 77.8675 | 19.4669 |

| 1500 | 19.5952 | 624.8633 | 78.1079 | 19.5270 |

| 1600 | 19.6698 | 626.4136 | 78.3017 | 19.5754 |

| 1700 | 19.7476 | 628.3030 | 78.5379 | 19.6345 |

| 1800 | 19.8287 | 632.4643 | 79.0580 | 19.7645 |

| 1900 | 19.9136 | 635.1324 | 79.3916 | 19.8479 |

| 2000 | 20.0023 | 635.9691 | 79.4961 | 19.8740 |

| 2100 | 20.0973 | 636.0710 | 79.5089 | 19.8772 |

| 2200 | 20.1975 | 636.6385 | 79.5798 | 19.8950 |

| 2300 | 20.3047 | 640.8559 | 80.1070 | 20.0267 |

| 2400 | 20.4206 | 644.3283 | 80.5410 | 20.1353 |

| 2500 | 20.5475 | 644.9098 | 80.6137 | 20.1534 |

| 2600 | 20.6891 | 646.9193 | 80.8649 | 20.2162 |

| 2700 | 20.8518 | 650.2284 | 81.2786 | 20.3196 |

| 2800 | 21.0501 | 656.0194 | 82.0024 | 20.5006 |

| 2900 | 21.3226 | 654.6274 | 81.8284 | 20.4571 |

| 2950 | 21.5519 | - | - | - |

| 2962.5 | 21.6575 | - | - | - |

| 2968.75 | 21.6575 | - | - | - |

| 3000 | - | 660.6206 | 82.5776 | 20.6444 |

The random velocities set by the MD calculation introduce an error in the calculated volume of the cell. This is taken account of by means of error bars in the comparative plots of the LD and MD thermal expansion computations given in figure 15.

The thermal expansion coefficients given by the two methods at the full spectrum of temperatures is given in table 9. It should be noted that these expansion coefficients were calculated by fitting a second-order polynomial trendline to the data in each case. Thermal expansion coefficients are given to two decimal places for clarity.

Although there appears to be a systematic error in the deviation of the calculated thermal expansion coefficients from the literature values there are still clear trends that may be identified in the data set. The error is likely due to the fact that different experimental techniques of measuring the coefficients are used. It is worth noting that the deviation from literature values was actually greater for a sixth order trendline fit to the data in the case of LD relative to a second order trendline. Such a marked discrepancy between simulation-predicted properties and experimentally determined ones is not uncommon in the literature 2.

Through examining the deviation from the literature values for both LD and MD the observer may identify temperature ranges over which one or the other method is more accurate. It is possible to identify from table 9 the key differences in the ability of LD and MD to match the literature values over different temperature ranges. Starting from 100 K it can be seen that MD overestimates the expansion coefficient and has a larger deviation from the literature value when compared to LD. The two methods begin to agree with each other near a middling temperature range of roughly 1400 K with the same deviation from the literature value to two decimal places. However at higher temperatures LD possesses the larger deviation from the literature values of the expansion coefficient. It is also worth noting that LD always predicts a higher volume per formula unit than MD not withstanding the error bars in the data points of the MD computation (a best-guess error of 2 cubic angstroms was identified for the calculated volume of the supercell in MD).

The differences displayed may be reconciled through considering the approximations made by each method. LD possesses strengths in so far as it takes into account zero-point vibrations and other quantum effects at low temperatures. However the model is seen to break down completely at temperatures nearing the melting point of MgO. This arises from the fact that LD fails to take true anharmonic effects into account. This feature of LD is most striking in and around the melting point when bonds begin to break. As this is not allowed in the quasi-harmonic approximation, LD ceases to function completely. Indeed, a good estimate of the melting point of MgO would appear to be the point at which this occurs. MD in contrast works quite well at higher temperatures and ultimately allows for bonds to break by accounting fully for anharmonic effects. However its weakness lies in predictions made at low regions of the temperature scale where quantum effects dominate 2. From table 8 one can see that the melting point of MgO was estimated by a bisection strategy. In other words the simulation failed to produce results at 3000 K and so the middle value between 2900 and 3000 was taken at 2950 K for the next computation. This procedure was followed until a range of 2962.5-2968.75 K was identified as the melting point range of MgO for the purposes of this simulation. This is within 200 K of the experimental melting point of 3125.15 K 9.

The 2x2x2 cell used for MD will produce estimates of similar accuracy to the 16x16x16 Monkhorst-Pack k-point mesh used in the LD simulations although the comparison between the two is not obvious. Firstly, MD uses repeat units of the conventional cell. LD uses a computed grid of k-points in reciprocal space. However, one can say qualitatively that the larger the cell used for simulation in real space, the smaller the Brillouin zone and so fewer k-points will be required for sampling. Hence in a qualitative fashion it could be said that the 2x2x2 cell in real space in MD will work approximately as well as the 16x16x16 k-point grid in reciprocal space in LD with regard to producing accurate energy values. One would need to perform further numerical calculations in order to provide a definite answer to this question.

In the quasi-harmonic approximation sequential calculations close to the melting point of MgO lead to increasing overestimation of the volume of the cell until eventually the approximation breaks down completely at the melting point of MgO. On the other hand however, MD is successful at accounting for volume expansion past the melting point. When an animation is run in MD around the melting point temperature one may observe the creation of a void inside the supercell as atoms vibrate at large amplitudes and begin to be displaced form their fixed positions in the lattice.

Conclusion

The vibrational modes of MgO were probed using the simulation techniques of lattice dynamics and molecular dynamics. Following on from the computation of the density of states, phonon dispersion and free energy of MgO using LD, a Monkhorst-Pack k-point grid mesh size was identified for use in the subsequent thermal expansion calculations. When the thermal expansion predictions of LD and MD were compared it was found that the methods showed a marked contrast in their performance within different ranges of the temperature. LD, invoking the quasi-harmonic approximation performed well in the ranges of low temperature wherein quantum effects have a sizeable influence on the thermal expansion. Conversely, MD with its purely classical assumptions, neglected quantum effects in this temperature range resulting in sizeable deviations from experimental literature values. In the high temperature range the situation was reversed with LD struggling to provide realistic predictions of the thermal expansion before collapsing completely within the range of 2962.5 - 2968.75 K. The failure of LD in this temperature range was a direct consequence of its inability to account for anharmonicity in the MgO crystal. MD functioned well in this temperature range and accounted for anharmonic effects by allowing the atoms to migrate from their fixed lattice positions at the melting point temperature.

One point of note is the fact that both simulation techniques gave results that were an order of magnitude removed from those predicted by experiment. As such, a logical extension to the experiment would be to replace the simple Buckingham potential with a more sophisticated model. A likely candidate for such a model would be one that took into account polarisability in the lattice. The thermal expansion data from different models could then be compared against experimental literature values with the aim of finding the features of the model that provides the best fit to the data. In this case some key insights could be made into the predominant contributions to thermal expansivity and other thermodynamic properties of periodic solids such as MgO.

References

1. A. R. Oganov, M. J. Gillan, G. D. Price, J. Chem. Phys. , 2003, 118, 10174

2. D. Fincham, W. C. Mackrodt, P. J. Mitchell, J. Phys.: Condens. Matter. , 1994, 6, 393-404

3. J. D. Gale, J. Chem. Soc. , Faraday Trans. , 1997, 93(4), 629-637

4. H. J. Monkhorst, J. D. Pack, Phys. Rev. B:Condens. Matter. , 1976, 13, 5188

5. 10.6 Number of k-points and method for smearing, http://cms.mpi.univie.ac.at/vasp/guide/node172.html (accessed November 2014)

6. Requesting Vibrational Properties, http://www.tcm.phy.cam.ac.uk/castep/documentation/WebHelp/html/tskcastepreqvibprops.htm (accessed November 2014)

7. R. G. Della Valle, E. Venuti, Phys. Rev. B1, 1998, 58, 206-212

8. O. L. Anderson, K. Zou, J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data, 1990, 19(1), 69

9. C. Ronchi, M. Sheindlin, J. Appl. Phys. , 2001, 90, 3325