Rep:Mod:Pfv611

The Cope Rearrangement Tutorial

Introduction

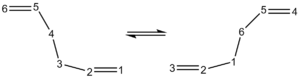

The Cope Rearrangement is the isomerization of a 1,5-diene leading to a regioisomeric 1,5-diene. The mechanism involves a [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement that shifts single and double bonds between two allylic components, and its main product is the thermodynamically more stable regioisomer[1].. Many variations are known, such as the Oxy-Cope[2](which has a hydroxyl substituent on an sp3-hybridized carbon of the starting isomer), or the similar Aza-Cope rearrangements (in which the heteroatom is a nitrogen atom).

The spefic rearrangement studied in this part of the module is that of 1,5-hexadiene, shown in Scheme 1. To fully investigate the stereoelectronics involved in the process a few conformers of this molecule have been studied. 1,5-hexadiene contains three readily rotating carbon-carbon bonds, which each have three rotational minima. However due to steric and electronic interactions only 10 are energetically distinct (and all 10 can be found in [Appendix 1]. In this case only the ones pertinent to the discussion have been modeled.

Additionally, ab initio computational methods have been used to model both possible Transition States, to investigate whether the rearrangement is more likely to go through one or the other. It is worth pointing out that the assumption about this reaction undergoing a concerted transition state mechanism is based on numerous studies that have already been done on the subject [3][4].

The computations performed within this part of the module are parallel to the ones described in [this study] by Rocque et al. (although they investigated a larger range of computational techniques, including for example coupled clusters operators).

Conformers of 1,5 - hexadiene

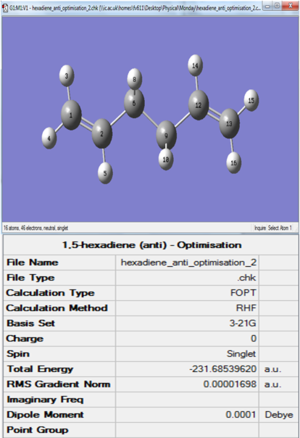

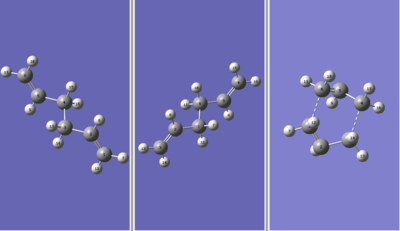

"anti 1"

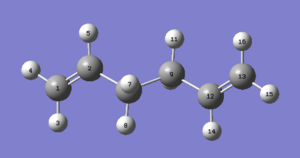

The first molecule of 1,5-hexadiene was drawn on GaussView with a simil-anti periplanar arrangement of the four central Carbon atoms. The structure was cleaned and then an Hartree-Fock 3-21G optimisation was set up and run on Gaussian. The resulting optimised structure and its energy (which was found to be -231.68539620 AU) can be seen in Figure 1. This figure also shows that the optimised molecule did not have a specific point group. Using the Symmetrize function under the Edit menu cleaned up the structure again and assigned a C2h point group to this molecule.

However, an analysis of the script's [Appendix 1] showed that the energy of this conformer was too high to be any of the possible minima. One possible reason might be that the optimisation converged to a maximum (which on the PES would correspond to a transition state) instead of a minimum. To confirm this hypothesis, a Frequency Analysis was run on the optimised molecule. The Frequency Analysis essentially corresponds on taking a second derivative of the potential energy profile, hence finding negative frequencies (that can be seen below) in the *.log file confirmed the identity of the stationary point to which the optimisation converged to be a maximum.

Low frequencies --- -138.2699 -96.2612 -2.7014 -2.0685 -0.0003 0.0005 Low frequencies --- 0.0007 6.1233 119.3777 ****** 2 imaginary frequencies (negative Signs) ******

Analysis of the movemements responsible for the negative frequencies provided insights on which atoms were responsible for such vibrations (the four Hydrogens on C(5) and C(9)) and a new optimisation was run with the same parameters after moving these hydrogens.

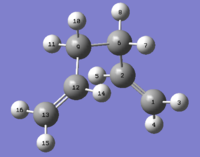

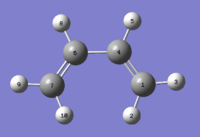

The newly optimised molecule can be seen in Figure 2 and its energy (-231.69260236 AU, from the *.log file found here) and point group (C2, found after symmetrizing the molecule) confirm its identity as the anti 1 conformer.

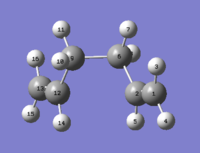

"gauche 2"

With the aim of exploring the minimum energy conformers the configuration of the optimised anti 1 molecule was changed by changing the dihedral angle of the four central Carbon atoms from 180° to 60°. After optimising this second structure (that can be seen in Figure 3) and recording its energy as -231.69166702 AU (from its specific *.log file) and its point group as C2 we can identify it as the gauche 2 conformer.

Comparing the energy of the two conformers shows that this one has a higher energy and although this might suggest that gauche- orientations are higher in energy than anti- ones some additional investigations will be necessary to confirm this hypothesis.

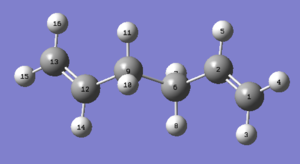

"gauche 4"

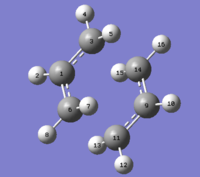

To see whether a greater distortion of the dihedral angle necessarily involves a higher energy, the dihedral angle of the optimised anti 1 was changed to 0°, to reach a fully eclipsed conformation. The resulting structure was optimised (Figure 4) and the output file was inspected to reveal an energy of -231.69153036 AU and a C1 point group. When comparing this data with [Appendix 1] the identity of this molecule as a gauche 4 conformer can be safely assumed.

The energy of this conformer confirms that a greater distortion involves a higher energy conformer. A smaller distortion (from 180° to 120°) was also tried but Gaussian optimised it to the same gauche 2 conformer.

"gauche 3"

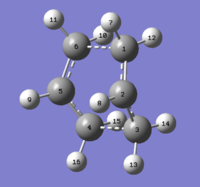

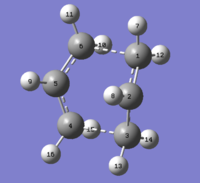

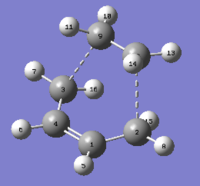

Although the results obtained indicate the anti 1 conformer as the lowest energy one, a look over [Appendix 1] revealed that the lowest conformer of all is in fact the gauche 3 one, so this molecule was drawn on GaussView and optimised by Gaussian. The resulting structure can be seen in Figure 5 and its output file reports an energy of -231.69266122 AU and a C1 point group, proving the conformer's identity as gauche 3.

The exceptional stability of this specific conformer can be rationalised by invoking the gauche effect . The orientation of the four central C-C single bonds with respect to the central C-H bonds is optimal from an orbital overlap perspective: as can be seen in Figure 6, the σC-H and the σ*C-C overlap very well, in both symmetrical sides of the molecule. This results in very strong hyperconjugation and stabilises the gauche 3 conformer. It is worth noting that although other gauche conformers have the same orbital overlap, gauche 3 is the one in which the C=C groups are positioned as far away as possible, and in which unfavourable steric interactions are minimised. It is also the only conformations where two sets of bonds can interact in this way, and hence the only one where electronics win over the diaxial steric repulsions. Indeed the two successive conformations in order of increasing energy are both anti.

"anti 2"

Since none of the previously optimised conformers had been identified as anti 2, this conformer was drawn on GaussView and a series of optimisations were run on Gaussian. The first one was run with the same parameters as the optimisations presented above, ie. Hartree-Fock method and 3-21G basis set. The second optimisation was instead run using the DFT - B3LYP method, using the more complete 6-31G(d) basis set. A Frequency Analysis was then run on both levels of theory, both at RT and at 0K. A summary of all the calculations mentioned is presented in Table 1.

| HF/3-21G (*.log file here) | DFT(B3LYP)/6-31G(d) (*.log file here) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Electronic Energy (Eelec) | -231.69253528 | -234.61171035 | ||

| Point Group | Ci | Ci | ||

| RT (298.15 K) (*.log file of the Frequency Analysis can be found here) |

0 K (*.log file of the Frequency Analysis can be found here) |

RT (298.15 K) (*.log file of the Frequency Analysis can be found here) |

0 K (*.log file of the Frequency Analysis can be found here) | |

| IR spectra |  |

|

|

|

| Zero - point Vibrational energy | -231.539540 | -231.539540 | -234.469203 | -234.469203 |

| Sum of Electronic and Thermal energies | -231.532566 | -234.461857 | ||

| Sum of Electronic and Thermal Enthalpies | -231.531622 | -234.460913 | ||

| Sum of Electronic and Thermal Free Energies | -231.570913 | -234.500777 | ||

Comparison of the two optimised geometries did not reveal any significant difference, but the higher level of theory did reach a minimum that was lower in energy. The frequency analyses that were run on each level of theory proved that it was indeed a minimum (no negative frequencies were reported, characteristic of a transition state). This can be trivially rationalised by considering the higher complexity of the 6-31G(d) basis set, which contains functions that are better able to follow the Potential Energy Surface to its minimum. The different frequency of vibration sets are also very similar, but the intensity values of such vibrations after the 6-31G(d) optimisation are between half and two thirds of the ones obtained after a Frequency Analysis and the temperature doesn't seem to have an effect on either frequency or intensity. This last observation might seem counter intuitive one might expect vibrations to be significantly less important near 0K. However the difference in intensity encountered when switching to a better basis set can be explained by remembering the lower overall energy of the optimised molecule. The energy difference between the two theory levels is actually 1831.81 kcal/mol, a considerable number that could explain the lower energy allocated for each vibration, hence the lower intensities of the frequency spectrum.

The zero-point energy does not change when lowering the temperature, but since all other energies computed during the Thermochemistry analysis are derived from the zero-point one by adding in considerations directly or indirectly related to the temperature these values will equal the zero-point energy for all computations set at 0K.

Optimising the "Chair" and "Boat" Transition Structures

Allyl fragment

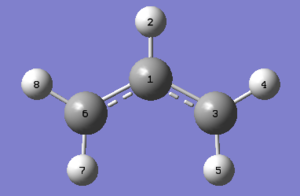

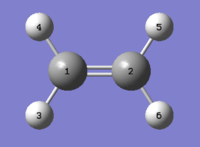

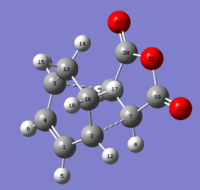

A CH2CHCH2 fragment was drawn on GaussView and optimised through the HF/3-21G method. Such optimised fragment had an energy of -115.82303830 AU and is shown in Figure 7.

The optimised fragment was used to draw a simil-chair transition state structure to serve as an input for various optimisations. A distance of 2.2 Å was set between the four Carbon atoms that would be the extremes of the new bonds, to ensure that Gaussian would not mistake these for already formed bonds when optimising (since distance between atoms is the only factor taken into consideration by Gaussian when determining whether a bond exists or not). Also this distance is smaller than the sum of the Van der Waals radii of the two carbons and as such is a plausible distance for atomic interactions. The guess structure obtained is shown in Figure 8, highlighting the atoms whose distances have been changed.

Chair Transition Structure - Hessian Optimisation

The guess structure for the Chair Transition State shown in Figure 8, which we know to be close to the "real" Transition State structure [4], was used as an input file for a manual optimisation by computing the Hessian force matrix.

Such optimisation to a Transition State (Berny) was done under the 3-21G basis set (Hartree-Fock method), with the addition of the noeigen keyword, that avoids crashing in case the guess structure isn't good enough. A Frequency Analysis was run alongside the optimisation: this include calculating the normal mode force constants (i.e. the second derivatives of the PES in a diagonalised coordinate system).

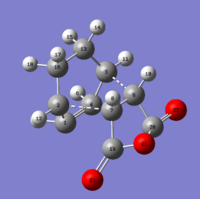

The optimised structure can be seen in Figure 9 and has an energy of -231.61932239 AU. Analysis of its *.log file showed the expected negative frequency around -817.9 cm-1. The atom movements corresponding to each frequency of vibration can be animated in GaussView and in this specific case it is very useful to confirm that the negative frequency (the one indicating negative curvature and so confirming the identity of the optimised molecule as a Transition State) indeed corresponds to the Cope Rearrangement. This is shown in Figure 10, which clearly shows one bond breaking and one forming, as expected in a Cope rearrangement.

The optimised distances between the Carbon atoms involved in the Transition State processes were recorded as 2.0206 Å and the point group was found to be C2h, matching what is reported in [Appendix 2].

Chair Transition Structure - Frozen Coordinates Optimisation

A second optimisation method was tried in order to compare it with the Hessian one. This method involves two steps, the first one being the optimisation of every part of the molecule but the atoms forming the extremities of the bonds involved in the Transition State processes, which stay at fixed distanced (hence the name "frozen coordinates"). The second step calculates the second derivative across the whole molecule starting from the checkpoint file resulting from the first optimisation (*.log output can be found here), aided by the fact that most of it is already in its optimised state and so the structure is supposed to be good enough not to require any force constant calculation.

As expected, the first step of the optimisation did not change the distance between the atoms that had been fixed which stayed 2.2 Å apart, whereas this distance goes down to 2.02 Å after the second step (the related *.log file can be found here). This distance matches the one resulting from the Hessian Optimisation method and can be used to hypothesise that both optimisations methods will yield equivalently optimised structures. To confirm this we can check the energy of the "frozen coordinates"-optimised structure. At -231.61932233 AU and with point group C2h, the energy and symmetry also coincide and confirm that we can consider the two optimisation methods equal for this specific system. Additionally inspection of the negative frequency and it corresponding atom movements mirrors the ones depicted in Figure 10 and is further proof of the validity of the hypothesis stated above.

Figure 11 shows the shortening of the interatom distance upon completion of the second step of the optimisation.

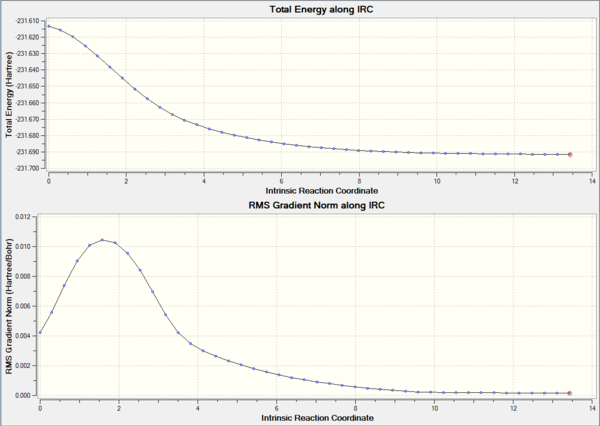

IRC Calculations from Optimised Chair Transition Structures

The Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC) is a special case of the Minimum Energy Path (MEP) connecting reactants, transition states and products. In fact the IRC is a plot of the energy of each structure along the minimum energy path vs the root-mean-square change in the mass weighted Cartesian coordinates relative to the TS structure. The TS thus has a x-coordinate of zero, while structures leading to the reactants are defined by negative (Root Mean Square Derivatives) values.

If the energy is plotted against something else, such as a bond-length, then it is simply a minimum energy path. Because an IRC uses mass-weighted coordinates, using different isotopes will lead to different IRCs, and one use of IRC is to determine tunneling corrections to the reaction rate. However the main reason IRC analyses have been conducted within this module is to check whether the TS actually connects the reactants and products we think it does.

From the Hessian-Optimised Chair Transition Structure

Observing the output file of the Hessian-optimised chair Transition State seems to suggest that the product of the reaction going through this TS will be gauche 2 (from inspection of the relative orientations of the two parts of a molecule that will become double bonds in the product). To check if this is actually the case we can try investigating the path of reaction along the Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC).

The IRC calculation can be set up on Gaussian to be computed only in the forward direction (since the vibration with negative frequency identifying our structure as a Transition State, shown in Figure 10, is symmetrical and as such a computation in either direction would yield the same path). The force constants are also computed at each point and the number of steps was chosen to be 50.

The resulting reaction path can be seen in Figure 12. This optimisation took 44 steps but at the energy of the last step (the one in which the IRC terminated) was -231.61932239 AU, a value higher than any of the conformers listed in [Appendix 1], indicating that the IRC calculation probably got stuck in proximity of (but not exactly on) the minimum. Further confirmation of this idea can be found by inspecting the Reaction Path Plots producted by GaussView, shown in Figure 13. Although the direction of the movement is right (every step results in a structure with lower energy), a look at the gradient plot shows that the gradient in step 44 is not exactly zero. Since the gradient does get lower and lower (implying that the energy difference between each IRC step becomes smaller) we can hypothesize that the threshold for which Gaussian recognized an IRC minimum was just set too loosely.

To correct this and try to obtain an actual minimum energy conformer an HF/3-21G optimisation was set to be run on the last step of the IRC (step 44). Such optimised structure can be seen in Figure 14, its *.log file can be seen here and the energy of this conformer, recorded as -231.691667702 AU matches the one recorded for the gauche 2 conformer, fitting our original hypothesis.

From the Chair Transition Structure Optimised through the Frozen Coordinates Method

The same IRC computation was repeated using the "frozen coordinates"-optimised structure as starting point. As before, this transition state is characterised by the same symmetrical vibration and as such the IRC needs only to be calculated in either direction. This time the IRC stopped after 43 steps out of 50 (the reaction path can be seen in Figure 15). The results were predictably very similar, given the close resemblance between the two differently optimised structures. As previously, the IRC computation stopped in a region of the PES with very low curvature, but where the energy of the molecule (-231.69159092) was still too high for it to be one of the possible minima (this was also confirmed by the gradient on step 43 being different from zero, as can be seen in Figure 16).

As previously an optimisation was run to try to reach a minimum energy conformer (see *.log file here). The result of the optimisation can be seen in Figure 17 and the energy again corresponds to the gauche 2 conformer. This confirms the previously observed equivalency of the two methods for optimising a molecule to the Transition State (Hessian computation and Frozen Coordinates method).

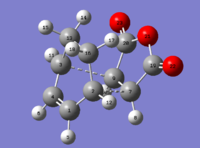

Boat Transition Structure - QST2 Optimisation

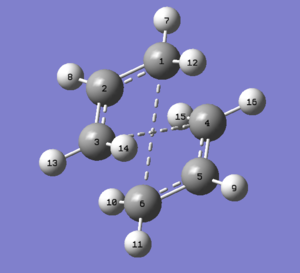

Another method of optimisation was explored when aiming to optimise the Boat Transition State structure: the QST2 optimisation, which instead of starting from a guess structure for the TS estimates it after being given the structures for the respective reactants and products. Since we are analysing a rearrangement reaction the reactant and product have the same empirical formula and they only differ in the order in which the carbon atoms are linked between them. Figure 18 illustrates this concept, and describes how the atoms have been numbered in GaussView before setting up the Optimisation.

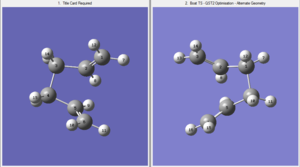

An Optimisation to a TS (TS(QST2)) was then set up along side a Frequency Analysis, starting from reactant/product geometries equivalent to those sketched in Figure 18. The resulting checkpoint file (corresponding to this *.log file)can be seen in Figure 19 and it is evident that it looks more like a Chair TS than a boat one. Indeed we would expect the Boat structure to have C(2) and C(5) eclipsing each other rather than staggered like in Figure 19. This is because when provided with this level of information Gaussian does not consider the possibility of rotating our molecule about the central C-C bond and so we have to add this information in manually.

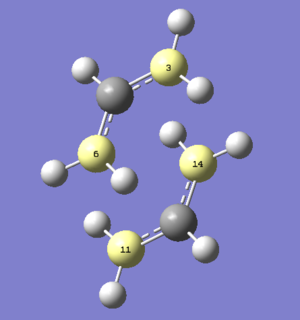

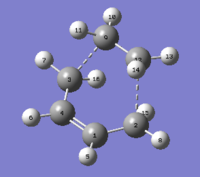

To do this, the C(5)-C(4)-C(3)-C(2) (in the reactant molecule) and the C(5)-C(6)-C(1)-C(2) (in the product molecule) dihedral bond angles were changed to 0° and the amplitude of both molecules was reduced by changing both internal C-C-C angles to 110°. This resulted in the input file shown in Figure 20. The same file was used as a starting point for an Optimisation and Frequency Analysis run on the same parameters as the previous, which yielded a plausible Boat Transition structure, shown in Figure 21, with energy of -231.60280237 and a C2v (as predicted by [Appendix 2]). Further analysis of the *.log file showed only one negative frequency (see below) and visualisation of the atom movements corresponding to that specific frequency (which turned out to be the bond-breaking and forming expected from the TS, as can be seen in Figure 22) confirmed the effectiveness of this TS optimisation.

Low frequencies --- -840.3862 -2.3604 -0.0005 -0.0005 -0.0002 4.6422 Low frequencies --- 7.5669 155.3550 382.2450 ****** 1 imaginary frequencies (negative Signs) ******

Boat Transition Structure - QST3 Optimisation

To try and circumvent the problem of having to position the atoms in the reactants and products in a certain geometry in order for the optimisation to work a more complex optimisation was set up. The QST3 method involves adding a Transition Structure guess to the reactant and products and as such extrapolating the "real" Transition State Structure from three terms instead of two. This three-component input file (shown in Figure 23) was then used to run an Opt+Freq calculation to TS(QST3) (*.log file shown here), which resulted in the Transition Structure shown in Figure 24. This molecule was found to have an energy of -231.60280247 and a C2v, matching perfectly with the results of the QST2 optimisation, supporting the hypothesis that this is the molecule we are looking for and proving the advantage of using a QST3 optimisation when in possess of an idea of what the TS looks like(indeed this method avoided the problem of having to manually modify the relative angles in reactants and products).

The Frequency computation was also analyzed to confirm the presence of a true Transition State and to observe the atom movements associated with Transition State processes. The Low Frequencies reported below and the vibrational movement shown in Figure 25 also coincide with the results of the QST2 optimisation.

Low frequencies --- -839.9512 -0.4148 -0.0005 -0.0004 0.0005 1.4035 Low frequencies --- 2.9592 155.2986 381.9449 ****** 1 imaginary frequencies (negative Signs) ******

Comparing the Activation Energies towards Chair and Boat Transition Structures on different levels of Theory

| HF/3-21G | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic energy [H] | Sum of electronic and zero point energy (0K)[H] |

Sum of electronic and thermal energies (298.15 K) [H] | |

| Chair TS - Hessian Opt | -231.6193224 | -231.466701 | -231.461341 |

| Boat TS - QST2 Opt | -231.6028024 | -231.450929 | -231.445301 |

| anti2 | -231.6925353 | -231.53954 | -231.532566 |

| B3LYP/6-31G* | |||

| Electronic energy [H] | Sum of electronic and zero point energy (0K) [H] | Sum of electronic and thermal energies (298.15 K)[H] | |

| Chair TS - Hessian Opt | -234.556983 | -234.414924 | -234.409003 |

| Boat TS - QST2 Opt | -234.543093 | -234.402337 | -234.396003 |

| anti2 | -234.6117104 | -234.469203 | -234.461857 |

| Electronic energy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G* | ||||

| [H/p] | kcal/mol | [H/p] | [kcal/mol] | ||

| ΔE (Chair) | 0.07321289 | 45.94174739 | 0.05472737 | 34.34191722 | |

| ΔE (Boat) | 0.08973291 | 56.30820862 | 0.06861733 | 43.05799213 | |

| Sum of electronic and zero point energy (0K) | Experimental Values | ||||

| HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G* | ||||

| [H/p] | [kcal/mol] | [H/p] | [kcal/mol]] | [kcal/mol] | |

| ΔE (Chair) | 0.072839 | 45.70712805 | 0.054279 | 34.06056101 | 33.5 ± 0.5 |

| ΔE (Boat) | 0.088611 | 55.6042 | 0.066866 | 41.95901679 | 44.7 ± 2.0 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal energies (298.15 K) | |||||

| HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G* | ||||

| [H/p] | [kcal/mol] | [H/p] | [kcal/mol] | ||

| ΔE (Chair) | 0.071225 | 44.69432852 | 0.052854 | 33.16636069 | |

| ΔE (Boat) | 0.087265 | 54.75957289 | 0.065854 | 41.32397769 | |

Overall the values coincide reasonably well with the experimental values, especially when considering the ones obtained using the B3LYP/6-31G* basis set. This can be rationalised by considering the higher level of complexity involved in this basis set. Predictably all the Activation Energies calculated at room temperature are lower than the ones calculated at 0K (increased ambient temperature means reactions are generally favoured). A last noticeable point is that all the Activation Energies calculated for the reaction path involving the Chair Transition State are smaller than the ones leading to the Boat Transition Structure. This suggests that the Chair TS is the major TS (rationalisable by considering the lower steric interactions within it).

The Diels-Alder Cycloaddition

Introduction

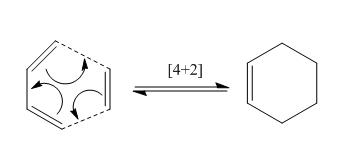

The Diels–Alder reaction is a [4+2] cycloaddition between a conjugated diene and a dienophile (either reactant can be substituted), to form a substituted cyclohexene system. It was first described by Otto Paul Hermann Diels and Kurt Alder in 1928[5]. The Diels–Alder reaction is particularly useful in synthetic organic chemistry as a reliable method for forming 6-membered systems with good control over regio- and stereochemical properties. Variations involving heteroatom-containing π-systems are also known and are usually termed hetero-Diels-Alder reactions. Diels–Alder reactions can be reversible under certain conditions; the reverse reaction is known as the retro-Diels–Alder reaction.

In this part of the module two specific systems are investigated: the simplest one, involving the addition of ethylene to cis-butadiene and a more complex system used to address regioselectivity issues, consisting in the reaction of cyclohexadiene and maleic anhydride. These reactions are respectively illustrated in Scheme 2 and Scheme 3.

Cis-Butadiene

Optimisations (AM1, HF/3-21G and DFT/B3LYP/6-31G(d)) and Considerations on HOMOs and LUMOs

A Cis-butadiene molecule was drawn on Gaussian and optimised three consecutive times, each times on a deeper level of theory. The first method used was the Semi-Empirical/AM1 method, then the two others theory levels already explored. What differentiates this method from the latter is that this is not an ab initio calculation, meaning that it uses a database of previously known and empirically measured molecules to predict the results for the system it is investigating. HF and DFT methods calculate everything from scratch.

Table 4 Summarises the results of all these optimisations.

| Semi-empirical/AM1 Optimisation | HF/3-21G Optimisation | B3LYP/6-31G* Optimisation | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| See *.log file here | See *.log file here | See *.log file here | ||||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||||

| Energy [H/p] | 0.04878534 | -154.05514025 | -155.98648969 | |||||||||

| Point Group | C2 | C2 | C2 | |||||||||

| HOMO |

|

|

| |||||||||

| EHOMO | -0.34455 | -0.33420 | -0.23115 | |||||||||

| LUMO |

|

|

| |||||||||

| ELUMO | 0.01796 | 0.13841 | -0.02280 |

Although different levels of theory are not comparable, results like these underline the fundamental difference between semi-empirical (AM1) and ab initio (HF and DFT) calculation. Indeed the results of the two latter optimisations are much closer than to the former one. This is seen both in the Energy Values and in the shape of the Frontier Orbitals, which present a significantly higher amount of delocalisation when computed ab initio. It might be interesting to note that although electronic energies and MOs vary upon changing the computational method (the former more than the latter) the optimised geometries are basically the same across the three methods used.

With respect to symmetry, we can see that the HOMO of cis-butadiene is antisymmetric with the plane (it only presents one node), while the LUMO (containing two nodes) is symmetric.

Ethylene

Optimisations (AM1, HF/3-21G and DFT/B3LYP/6-31G(d)) and Considerations on HOMOs and LUMOs

After optimising the diene, ethylene was selected as a dienophile for our model Diels-Alder reaction and optimised using the same three methods.

Results are summarised in Table 5

| Semi-empirical/AM1 Optimisation | HF/3-21G Optimisation | B3LYP/6-31G* Optimisation | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| See *.log file here | See *.log file here | See *.log file here | ||||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||||

| Energy [H/p] | 0.02619024 | -77.60098737 | -78.58745822 | |||||||||

| Point Group | D2h | D2h | D2h | |||||||||

| HOMO |

|

|

| |||||||||

| EHOMO | -0.38777 | -0.37970 | -0.26665 | |||||||||

| LUMO |

|

|

| |||||||||

| ELUMO | 0.05284 | 0.18659 | 0.01880 |

As for cis-butadiene the energies are very different and the optimised geometries are almost identical, however this time the shape of the Frontier Orbitals is very similar. This could be rationalised by considering the smaller size and hence the simpler structure of ethylene when compared to cis-butadiene. This makes it easier even for the lowest levels of theory to afford a precise description of the MOs.

Analysis of Diels-Alder Transition Structures

Hessian Optimisation (HF/3-21G) and HOMO-LUMO considerations

Since the first part of the module had already demonstrated similarities and relative advantages and disadvantages when comparing Hessian and Frozen Coordinates Optimisations to Transition Structure States the former optimisation method was chosen to be run because a reasonable idea of what the TS is supposed to look like is known. The guess structure is shown in Figure 26 and the results of the optimisation based on the two selected basis sets are summarised in Table 6. Note that only ab initio calculations have been run since they will yield a more accurate result, particularly in the case of a bigger molecule like the Transition state.

Optimisations on both levels of theory successfully led to a Transition State Structure, as can be seen in Figure 27 and Figure 28 that respectively illustrate the modes of vibration corresponding to Transition State Processes in both the HF/3-21G and B3LYP/6-21G* optimised molecules. The Low Frequencies lines of the *.log files are also reported.

- HF/3-21G

Low frequencies --- -818.4710 0.0005 0.0007 0.0008 2.4476 3.3830 Low frequencies --- 4.8109 166.7257 284.3789 ****** 1 imaginary frequencies (negative Signs) *******

- B3LYP/6-21G*

Low frequencies --- -525.0240 -6.4641 -0.0008 -0.0005 0.0007 11.7980 Low frequencies --- 20.3153 136.2021 203.8186 ****** 1 imaginary frequencies (negative Signs) ******

| HF/3-21G Optimisation | B3LYP/6-31G* Optimisation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| See *.log file here | See *.log file here | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| -231.60320854 | -234.54389642 | |||||||

| Point Group | Cs | Cs | ||||||

| HOMO |

|

| ||||||

| EHOMO | -0.30086 | -0.21894 | ||||||

| LUMO |

|

| ||||||

| ELUMO | 0.14240 | -0.0862 |

Inspection of the outputted *.log files it can be seen that the terminal carbons have a separation of 2.27 Å (for the B3LYP/6-31G* optimised structure) and 2.21 Å (for the HF/3-21G optimisation), which is in good agreement with values found in the literature. It is interesting to note that this distance is in between the sum of the Van der Waals radii of two carbon atoms (3.40 Å) and the lengths of typical sp2 (1.34 Å) and sp3 (1.54 Å) C-C bonds, showing that this is a transition structure for the cycloaddition reaction, i.e. a bond has not yet been formed between the terminal carbons and there is a bonding interaction between the terminal carbons. Additionnally, the C-C bond in the middle of the cis-butadiene has a bond length of 1.41 Å, which is in between the length of an sp2 and an sp3 C-C bond, indicating a partly formed π-bond in the transition state.

To further confirm our idea of concerted mechanism, the vibrations and atom movements characterising the Transition State show that the bond formation is synchronous.

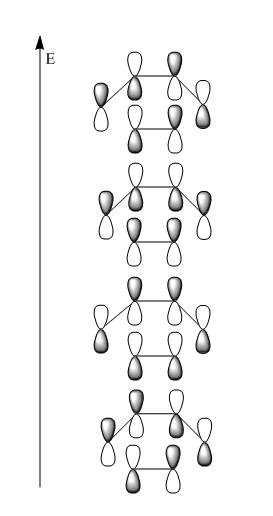

Both the HOMO and LUMO of the TS are Symmetric, which might seem counter-intuitive at first but can be easily rationalised when thinking of the possible LCAOs leading to product formation. Although only orbitals with the same symmetry will interact, and so the LCAOs are limited to the HOMO of cis-butadiene with the ethylene's LUMO and viceversa, each pair of orbitals can either be summed or substracted from each other, leading to four Frontier LCAOs in the cyclo-hexene transition state.

These are illustrated in Scheme 4. The HOMO-LUMO interactions are made really strong by the small energy gap between interacting orbitals of the reactants and by the presenceof favourable overlap of electron density and both these factors favour the reaction. As the MOs are very close in energy, using a different method and / or basis set for calculation might result in re-ordering of the MOs.

Activation Energies

| HF/3-21G | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic energy [H] | Sum of electronic and zero point energy (0K)[H] |

Sum of electronic and thermal energies (298.15 K) [H] | |

| TS - Hessian Opt | -231.60320854 | -231.451339 | -231.445651 |

| Cis-Butadiene | -154.05514025 | -153.963182 | -153.958759 |

| Ethylene | -77.60098737 | -77.545896 | -77.542938 |

| B3LYP/6-31G* | |||

| Electronic energy [H] | Sum of electronic and zero point energy (0K) [H] | Sum of electronic and thermal energies (298.15 K)[H] | |

| TS - Hessian Opt | -234.54389642 | -234.403324 | -234.396907 |

| Cis-Butadiene | -155.98648969 | -155.901143 | -155.896438 |

| Ethylene | -78.58745822 | -78.536231 | -78.533189 |

| Electronic energy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G* | ||||

| [H/p] | kcal/mol | [H/p] | [kcal/mol] | ||

| ΔE | 0.05291908 | 33.20719897 | 0.03005149 | 18.85758044 | |

| Sum of electronic and zero point energy (0K) | Experimental Values (HF/3-21G calculations[6] | ||||

| HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G* | ||||

| [H/p] | [kcal/mol] | [H/p] | [kcal/mol]] | [kcal/mol] | |

| ΔE | 0.057739 | 36.23174215 | 0.03405 | 21.36668145 | 35.9 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal energies (298.15 K) | |||||

| HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G* | ||||

| [H/p] | [kcal/mol] | [H/p] | [kcal/mol] | ||

| ΔE | 0.056046 | 35.16936941 | 0.03272 | 20.53209448 | |

As can be seen in Table 9 the calculated activation energies match the literature values.

Regioselectivity of Diels-Alder (Analysis of a Substituted System)

In order to investigate the effects of orbital overlap on the regioselectivity of the Diels-Alder cycloaddition reaction between cyclohxadiene and maleic anhydride reactants, transition states and products will have to be optimised and inspected. It was decided to optimise every molecule using both the HF/3-21G and DFT/6-31G* and to use the Hessian Optimisation path to the Transition Structure since it had been previously established to be equivalent for the needs of this experiment to the Frozen Coordinates, QST2 and QST3 methods.

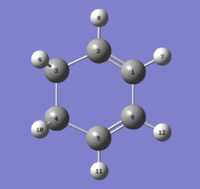

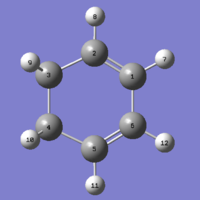

Cyclohexadiene

Optimisations (HF/3-21G and DFT/B3LYP/6-31G(d)) and HOMO and LUMO considerations

| HF/3-21G Optimisation | B3LYP/6-31G* Optimisation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| See *.log file here | See *.log file here | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Energy [H/p] | -230.53967047 | -233.41588487 | ||||||

| Point Group | C2v | C2v | ||||||

| HOMO |

|

| ||||||

| EHOMO | -0.29886 | -0.20102 | ||||||

| LUMO |

|

| ||||||

| ELUMO | 0.13780 | -0.01512 |

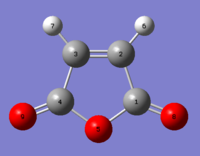

Maleic Anhydride

Optimisations (HF/3-21G and DFT/B3LYP/6-31G(d))and HOMO - LUMO considerations

| HF/3-21G Optimisation | B3LYP/6-31G* Optimisation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| See *.log file here | See *.log file here | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Energy [H/p] | -375.10351286 | -379.28954447 | ||||||

| Point Group | C2v | C2v | ||||||

| HOMO |

|

| ||||||

| EHOMO | -0.44750 | -0.29929 | ||||||

| LUMO |

|

| ||||||

| ELUMO | 0.02546 | -0.11711 |

It is interesting to note that for the first time we can see a vast difference in the shape of the MO (in this case the HOMO) when changing the theory level. This might be attributed to the influence of the heaver Oxygen atoms on the energy of the orbitals, which probably caused a disruption in their order when using the more complex basis set. So it is most probably not a deep change in the shape of the orbitals as such but more like a reordering of their energies.

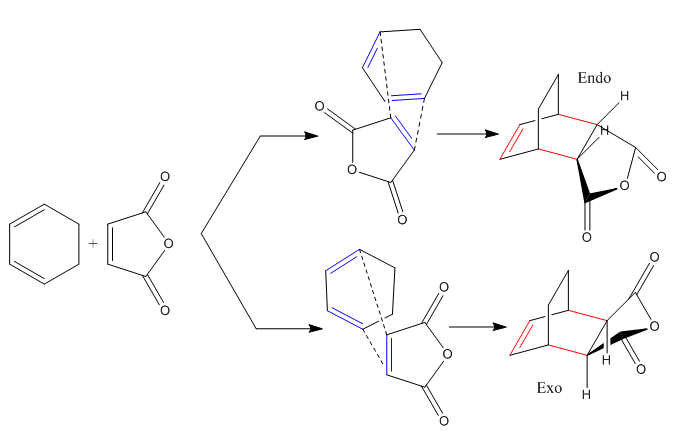

Exo Isomer Transition State Structure

Hessian Optimisation (HF/3-21G and B3LYP/6-31G* methods) and HOMO - LUMO considerations

Computing the Hessian Optimisation requires a Transition Structure Guess, which was drawn on Gaussian and is shown in Figure 31. This Guess Structure was then Optimised to a Transition State on two different levels of theory. Both Optimisations were run along a Frequency Analysis, which helped confirm the successful computation of a transition state through inspection of the Low Frequencies lines in the *.log files (shown below) and of the movements of the atoms correspondent to the negative frequency reported (that are indeed the movements of the atoms involved in the Transition State processes, as can be seen in Figure 32 and Figure 33).

- HF/3-21G

Low frequencies --- -647.5027 -1.3470 -0.9485 -0.3436 -0.0010 -0.0010 Low frequencies --- -0.0009 42.4065 131.4296 ****** 1 imaginary frequencies (negative Signs) ******

- B3LYP/6-31G*

Low frequencies --- -448.4393 -13.8022 -11.7567 -0.0006 0.0005 0.0006 Low frequencies --- 3.2822 53.4273 109.1532 ****** 1 imaginary frequencies (negative Signs) ******

| HF/3-21G Optimisation | B3LYP/6-31G* Optimisation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| See *.log file here | See *.log file here | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Energy [H/p] | -605.60359125 | -612.67931089 | ||||||

| Point Group | Cs | Cs | ||||||

| HOMO |

|

| ||||||

| EHOMO | -0.32325 | -0.24216 | ||||||

| LUMO |

|

| ||||||

| ELUMO | 0.05807 | -0.07841 |

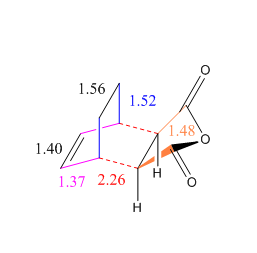

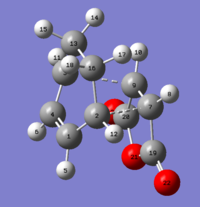

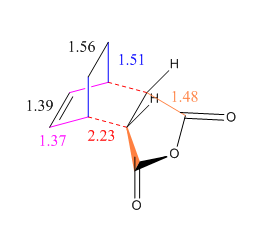

A more detailed description of the optimised geometry is shown in Scheme 5 and the distance between the maleic anhydride unit and the carbon bridge was found to be 3.10 Å.

Endo Isomer Transition State Structure

Hessian Optimisation (HF/3-21G and B3LYP/6-31G* methods) and HOMO - LUMO considerations

As before we require a Transition Structure guess, shown in Figure 34. Again, since a Frequency Analysis was run along the Optimisations there was a chance to confirm that the optimisations reached the Transition State. This was done in two ways: the inspection of the Low Frequencies lines in the respective *.log files (shown below) and the visualisation of the negative frequency reported, which for both levels of theory clearly shows movement of the four Carbon atom involved in the bond forming and breaking processes. These movements are shown in Figure 35 and Figure 36 for the HF/3-21G and B3LYP/6-31G* respectively.

- HF/3-21G

Low frequencies --- -818.4710 0.0005 0.0007 0.0008 2.4476 3.3830 Low frequencies --- 4.8109 166.7257 284.3789 ****** 1 imaginary frequencies (negative Signs) ******

- B3LYP/6-31G*

Low frequencies --- -446.9249 -14.0895 -0.0006 0.0005 0.0005 4.7821 Low frequencies --- 11.3165 59.7495 118.4609 ****** 1 imaginary frequencies (negative Signs) ******

| HF/3-21G Optimisation | B3LYP/6-31G* Optimisation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| See *.log file here | See *.log file here | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Energy [H/p] | -605.610368 | -612.6833966 | ||||||

| Point Group | Cs | Cs | ||||||

| HOMO |

|

| ||||||

| EHOMO | -0.32440 | -0.23506 | ||||||

| LUMO |

|

| ||||||

| ELUMO | 0.07332 | -0.06965 |

A more detailed description of the optimised geometry can be seen in Scheme 6 and the distance between the maleic anhydride unit and the double bond was found to be 3.00 Å. This is lower than the distance found for the Exo-TS which gives us a was of proving that the Endo structure for the Transition State is more sterically favoured.

Analysis of the shape of the MOs in both the Endo- and Exo- isomers shows that the orbitals have the same symmetry: the HOMOs of both Transition States are a combination of the HOMO of the cyclohexadiene and the LUMO of the maleic anhydride and are therefore asymmetric with respect to the plane. The favourable interactions between the п systems helps rationalised this reaction.

Indeed the preference for the endo- transition state can explained by considering the secondary orbital interactions (SOIs). SOIs were first defined as the positive overlap of a non-active frame (bonds which are not formed / broken in the reaction) in the frontier MOs of a pericyclic reaction (Woodward and Hoffmann[7]. In this case, the π-orbitals of the C=O bond in the endo- transition state (LUMO) interacts with the HOMO of the cyclohexadiene, providing a stabilising effect, which is absent in the exo- transition state.

Activation Energies

| HF/3-21G | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic energy [H] | Sum of electronic and zero point energy (0K)[H] |

Sum of electronic and thermal energies (298.15 K) [H] | |

| Exo TS - Hessian Opt | -605.6035913 | -605.408139 | -605.398679 |

| Endo TS - Hessian Opt | -605.610368 | -605.414907 | -605.405479 |

| Cyclohexadiene | -230.5396705 | -230.407711 | -230.403443 |

| Maleic Anhydride | -375.1035129 | -375.04291 | -375.038078 |

| B3LYP/6-31G* | |||

| Electronic energy [H] | Sum of electronic and zero point energy (0K) [H] | Sum of electronic and thermal energies (298.15 K)[H] | |

| Exo TS - Hessian Opt | -612.6793109 | -612.498013 | -612.487663 |

| Endo TS - Hessian Opt | -612.6833966 | -612.502143 | -612.49179 |

| Cyclohexadiene | -233.4158849 | -233.293211 | -233.288616 |

| Maleic Anhydride | -379.2895445 | -379.233665 | -379.228481 |

| Electronic energy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G* | ||||

| [H/p] | kcal/mol | [H/p] | [kcal/mol] | ||

| ΔE (Exo) | 0.03959208 | 24.84438653 | 0.02611845 | 16.38956244 | |

| ΔE (Endo) | 0.03281531 | 20.59190236 | 0.02203277 | 13.82576147 | |

| Sum of electronic and zero point energy (0K) | |||||

| HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G* | ||||

| [H/p] | [kcal/mol] | [H/p] | [kcal/mol]] | ||

| ΔE (Exo) | 0.042482 | 26.65783734 | 0.028863 | 18.11179227 | |

| ΔE (Endo) | 0.035714 | 22.41085643 | 0.024733 | 15.5201801 | |

| Sum of electronic and thermal energies (298.15 K) | |||||

| HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G* | ||||

| [H/p] | [kcal/mol] | [H/p] | [kcal/mol] | ||

| ΔE (Exo) | 0.042842 | 26.88374058 | 0.029434 | 18.47009991 | |

| ΔE (Endo) | 0.036042 | 22.61667938 | 0.025307 | 15.88037026 | |

It is worth noting that the endo- product has a slightly lower energy than the exo- product, further confirming the preference for this stereoisomer. This suggests that the endo-isomer is both kinetically and thermodynamically favoured.

Observation at the two stereoisomers showed that the distance between the carbonyl carbons of the dienophile and the nearest carbon on the diene is 3.00 Å for the endo-TS and 3.10 Å for the exo-TS. This indicates that the exo- form suffers from steric strain due to the close proximity of the bulky groups. Additionally, the -(C=O)-O-(C=O))- fragment in the exo- form points in the direction as the -CH2-CH2- fragment of the cyclohexa-1,3-diene ring, whereas that in the endo- form points in the direction of the diene (-CH-CH-). The extra hydrogens result in increase in steric repulsion between the groups, leading to an even more strained structure in the exo- transition state.

As expected the activation energy of the endo- adduct is lower than that of the exo- adduct, agreeing with the preference of endo- transition state.

Solvation Effects on the Endo Transition State Energy

| Solvent | Electronic Energy [H/p] | Relative energy | Dielectric Constant (as per lit.[8] at 20°) |

|---|---|---|---|

| No Solvent (See *.log file here) |

-612.6833966 | 1 | 0 |

| Heptane | -612.6894119 | 1.000009818 | 1.324 |

| Cyclohexane | -612.6897906 | 1.000010436 | 2.015 |

| Toluene | -612.6908489 | 1.000012163 | 2.2379 |

| Benzene | -612.6905737 | 1.000011714 | 2.274 |

| Diethyl ether | -612.6936271 | 1.000016698 | 4.34 |

| Chloroform | -612.6939977 | 1.000017303 | 4.806 |

| Chlorobenzene | -612.6945825 | 1.000018257 | 5.621 |

| Aniline | -612.6950739 | 1.000019059 | 6.89 |

| THF | -612.6952456 | 1.00001934 | 7.58 |

| Dichloro-methane | -612.6956194 | 1.00001995 | 9.08 |

| Dichloro-ethane | -612.6958391 | 1.000020308 | 10.36 |

| Acetone | -612.6966829 | 1.000021686 | 20.7 |

| Ethanol | -612.6968299 | 1.000021925 | 24.3 |

| Methanol | -612.6969948 | 1.000022195 | 32.63 |

| Nitro-methane | -612.697052 | 1.000022288 | 35.8 |

| Acetonitrile | -612.6970405 | 1.000022269 | 37.5 |

| DMSO | -612.6971559 | 1.000022457 | 46.78 |

| Water | -612.6973052 | 1.000022701 | 78.54 |

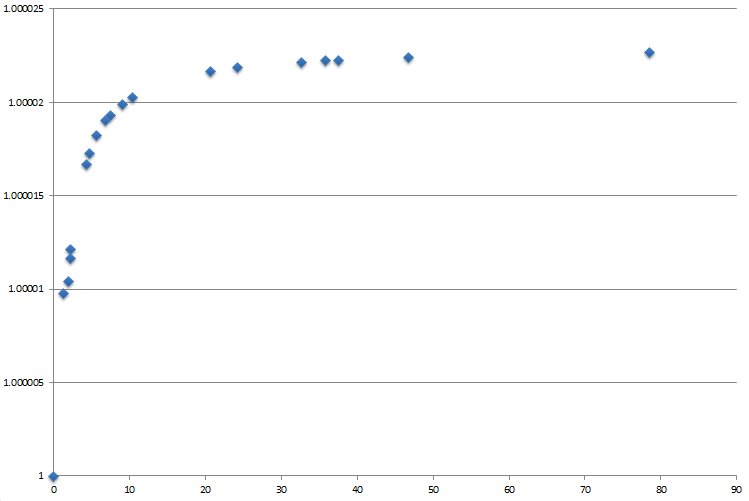

It was decided to investigate the effects of Solvation on the energy of the TS. Since it has already been shown that the Endo-TS is favoured, all calculations have been run starting from this regioisomer. They have all been run using the B3LYP/6-31G* method and compared to the energy of the TS when the Solvent Effects where not taken into considerations. As can be seen in Figure 36, a higher polarity has an exponential correlation on the energy of the TS and as such this characteristic should be taken into consideration when performing theoretical experiments, especially when trying to reproduce empirical data.

References

- ↑ Arthur C. Cope; et al.; J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1940, 62, 441

- ↑ A Synthesis of Ketones by the Thermal Isomerization of 3-Hydroxy-1,5-hexadienes. The Oxy-Cope Rearrangement Jerome A. Berson, Maitland Jones, , Jr. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964; 86(22); 5019–5020. doi:10.1021/ja01076a067

- ↑ Keiji. Morokuma , Weston Thatcher. Borden , David A. Hrovat, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1988, 110 (13), pp 4474–4475 DOI:10.1021/ja00221a092

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 David A. Hrovat , Keiji Morokuma , Weston Thatcher Borden, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1994, 116 (3), pp 1072–1076, {{DOI|10.1021/ja00082a032}

- ↑ Diels, O.; Alder, K. (1929). "Synthesis in the hydroaromatic series, IV. Announcement: The rearrangement of malein acid anhydride on arylated diene, triene and fulvene". Chemische Berichte 62 (8): 2081

- ↑ Robert D. Bach,* Joseph J. W. McDouall, and H. Bernhard Schlegel, J. Org. Chem, 1989, 54, 2931-2935

- ↑ B. Reffy, M. A. Fox, R. Cardona and N. J. Kiwiet,J. Org. Chem., 1987, 52, 1469-1474 DOI:10.1021/jo00384a016

- ↑ Table of Dielectric Constants of pure Liquids , Arthur A. Maryott and Edgar R. Smith, 1951