Rep:Mod:PVY714

Introduction

PES

A Potential Energy Surface (PES) shows the relationship between the energy of a molecule and its geometry. Stationary points, which have a gradient of zero, could be maximum, minimum or saddle points, and they correspond to structures of interest in a particular reaction.

Minima and saddle points

At a minimum point on a PES, the first derivative of the energy with respect to the geometry of a molecule is zero in all directions, and the second derivative is also positive in all directions[1].

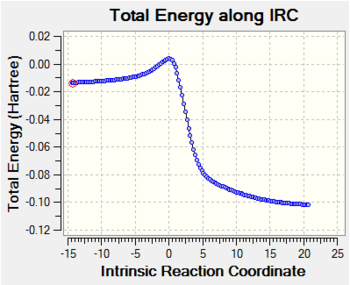

Conversely, a first-order saddle point is a maximum in one direction but a minimum in all other directions. Such a point corresponds to a transition state (TS). A TS links two minima on a PES, and it has one imaginary vibration. A good way to check that the correct transition state has been obtained is to animate the imaginary frequency: it should clearly show the motion of the atoms along the reaction coordinate[2]. Minima, on the other hand, only have real vibrations.

IRC

An Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate calculation (IRC) shows the path taken between two minima on a PES should the reactants acquire enough energy to overcome the activation barrier between those two minima[1]. The TS linking the two minima is always the highest point on the IRC.

In the following exercises, we identify and assess the transition states involved in several cycloaddition reactions, and we visualize reaction paths using IRC calculations.

Diels-Alder Reactions

A Diels-Alder reaction (DA) is the [4+2] cycloaddition of a diene and a dienophile. Exercises 1, 2, and 3 investigate the concerted, pericyclic nature of DA reactions, with a particular focus on the cyclic transition state. DA reactions are energetically favorable because of the formation of 2 new σ-bonds which are stronger than π bonds. A cheletropic reaction is another type of cycloaddition reaction, and it's explored in more detail in Exercise 3.

Orbital symmetry and electron demand

Overlap between the Frontier Molecular Orbitals (FMOs) of the diene and dienophile is required for a successful DA reaction. Overlap can only happen between orbitals of the same symmetry and of similar energy. This will be explained in more detail in Exercise 1.

DA reactions can proceed under normal or inverse electron demand. Under normal electron demand, the HOMO of the diene and the LUMO of the dienophile overlap; raising the HOMO of the diene or lowering the LUMO of the dienophile (for example, by introducing an electron-withdrawing group) promotes the normal reaction. Under inverse electron demand, an electron-donating group raises the HOMO of the dienophile and brings it closer to the LUMO energy of the diene, so the overlap is now between the HOMO of the dienophile and the LUMO of the diene. Again, this concept will be explored in more detail in the exercises below.

Methodology

All molecules and reactions were visualised with GaussView 5.

In Exercises 1 and 2, the reacting fragments were firstly optimised, then assembled in a guess structure of the TS. The distances between the reacting termini were 'frozen' to 2.2 Å (in-between the true value of a sp3 C-C bond the and the combined Van der Waals radii of two C atoms). The TS structure was initially optimised to a minimum then optimised to a TS (Berny). In Exercise 3, the process was started by drawing and optimising the product structures first, then working backwards to the transition state and reactants.

Exercises 1 and 3 employed the semi-empirical PM6 method which uses severe approximations but is good for initial optimisations and is also fast. In Exercise 2, all optimisations were initially carried out using PM6, followed by re-optimisation using the DFT method B3LYP, which provides more accurate results but is also significantly slower.

Nf710 (talk) 19:15, 20 January 2017 (UTC) Nice general intro, you could have also spoke about the various method you used in detail.

Exercise 1: Reaction of Butadiene with Ethene

Reaction Scheme

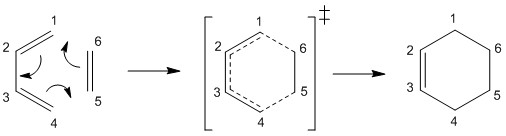

This exercise investigates the [4+2] cycloaddition reaction of butadiene and ethene. The reactants, transition state and products were all optimised at the PM6 level.

Molecular orbitals

A molecular orbital diagram for the formation of the TS is pictured below. It shows that four new molecular orbitals are formed from the combination of the FMOs of the diene and dienophile - 2 bonding and 2 anti-bonding; 's' stands for symmetric and 'a' stands for antisymmetric:

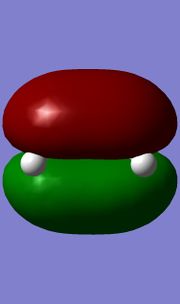

As was said in the introduction, orbital overlap is only possible between orbitals of the same symmetry and of similar energy, i.e. symmetric orbitals can overlap only with other symmetric orbitals, and antisymmetric orbitals can overlap only with other antisymmetric orbitals; both of these cases produce an orbital overlap integral of non-zero. On the other hand, overlap between a symmetric and an antisymmetric orbital is not possible because that gives an orbital integral of zero.

Each of the HOMO and LUMO of butadiene and ethene are displayed below, as well as the four MOs that they produce for the TS:

| Ethene HOMO (symmetric) | Ethene LUMO (antisymmetric) | Butadiene HOMO (antisymmetric) | Butadiene LUMO (symmetric) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| HOMO-1 (antisymmetric) | HOMO (symmetric) | LUMO (symmetric) | LUMO+1 (antisymmetric) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

It can be clearly seen that the HOMO of the TS is symmetric, which implies that it is made up of two symmetric components. The HOMO of ethene and the LUMO of butadiene are symmetric, so they must be the two FMOs that combine to give the TS HOMO. As explained in the introduction, this means that the reaction operates under inverse electron demand.

After carrying out the calculations, I updated my MO diagram to show the actual ordering of the 4 TS MOs:

Changing C-C bond lengths

All C-C bond lengths of the reactants, transition state, and products are tabulated below so that we can easily follow how the bond lengths change as the reaction progresses.

| C-C | Reactants | Transition State | Product |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-2 | 1.33530 | 1.37976 | 1.50034 |

| 2-3 | 1.46836 | 1.41111 | 1.33766 |

| 3-4 | 1.33530 | 1.37975 | 1.50034 |

| 4-5 | - | 2.11468 | 1.54003 |

| 5-6 | 1.32732 | 1.38175 | 1.54076 |

| 1-6 | - | 2.11501 | 1.54003 |

Bonds 1-2, 3-4, and 5-6 all increase in length as the reaction progresses, showing that they’re changing from double to single bonds. Conversely, bond 2-3 decreases in length showing that it’s changing from a single to a double bond. The Van der Waals radius of the C atom is 1.7 Å[3], whereas the lengths of the partly formed C-C bonds in the TS, 4-5 and 1-6, are 2.11468 Å and 2.11501 Å respectively. This shows that there are significant interactions between carbon atoms 4 & 5, and 1 & 6 in the TS.

Typical lengths of sp3 C-C and sp2 C-C are 1.53 Å[4] and 1.34 Å respectively[5]. The tabulated bond lengths of the product molecule are consistent with these literature values which shows that all calculations in the exercise were carried out correctly. Bond lengths 1-2 and 3-4 are consistent with typical sp2-sp3 C-C bonds which are 1.51 Å[4].

Vibrations

The TS calculation produced one imaginary frequency at -948.37cm-1. Animating i948.37cm-1 is a good way of showing that the correct TS has been obtained- it clearly displays which atoms in the two reacting fragments become connected (see the animation below). It also shows that the formation of the two new σ bonds is synchronous, which is what we would expect for a concerted cycloaddition reaction. The lowest positive frequency was found at 145.12cm-1 and it's also animated below. This vibration is not related to the reaction path. For completion, I have also included the IRC of the reaction, taking us from reactants to products via the TS.

| Animation of i948.37cm-1 | Animation of 145.12cm-1 | Animation of the IRC |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Nf710 (talk) 19:28, 20 January 2017 (UTC) Good first section but you havent shown understanding of Inverse/normal demand etc

Exercise 2: Reaction of Cyclohexadiene and 1,3-Dioxole

Reaction Scheme

This exercise investigates the [4+2] cycloaddition reaction of cyclohexadiene and 1,3-dioxole. The reactants, transition state and products were all initially optimised at the PM6 level, and then re-optimised at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level. This reaction can give two products as can be seen in the reaction scheme above. Both the endo and exo TSs were located and analysed. The endo TS had one imaginary vibration at -520.98cm-1, and the exo TS had one imaginary vibration at -528.82cm-1.

Molecular orbitals

Below, I’ve included the Jmols for both the HOMO and LUMO of cyclohexadiene and 1,3-dioxole, as well as the four MOs that they produce for each of the endo and exo TSs. I’ve also labelled each MO as symmetric (s) or antisymmetric (as) to make it clearer which reactant FMOs contribute to which TS MOs:

| Cyclohexadiene HOMO | Cyclohexadiene LUMO | 1,3-Dioxole HOMO | 1,3-Dioxole LUMO | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| HOMO-1 | HOMO | LUMO | LUMO+1 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| HOMO-1 | HOMO | LUMO | LUMO+1 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

The HOMO of both endo and exo TSs is symmetric. As was said earlier, an overlap can only occur between orbitals of the same symmetry. This means that the TS HOMO was formed from the overlap between the symmetric HOMO of 1,3-dioxole and the symmetric LUMO of cyclohexadiene. The two oxygen atoms in the dioxole act as electron donating groups because they each have two lone pairs of electrons; thus the energy of the dienophile HOMO is raised and becomes closer to the LUMO energy of the diene (see Exercise 1, Figure 3). Similarly to Exercise 1, a combination of the HOMO of the dienophile and the LUMO of the diene means that the reaction is inverse electron demand Diels-Alder.

Thermodynamic data

The reaction barriers and reaction energies for both endo and exo cases were calculated in order to determine the kinetic and thermodynamic products. The reactant and product structures were taken from the end-points of each IRC, and were then minimised. These minimised structures gave the reactant and product energies included in the table below.

| Reactants | Transition State | Products | Reaction barrier | Reaction energy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exo (Hartree/Particle) | -500.369574 | -500.329163 | -500.413535 | -0.043961 | 0.040411 |

| Exo (kJ/mol) | -1313720.41661 | -1313614.31752 | -1313835.83623 | 106.099089 | -115.4196143 |

| Endo (Hartree/Particle) | -500.366275 | -500.33215 | -500.414646 | -0.048371 | 0.034125 |

| Endo (kJ/mol) | -1313711.75509 | -1313622.1599 | -1313838.75316 | 89.5951943 | -126.9980702 |

19:32, 20 January 2017 (UTC) What level of theory is this?

From the results above, we can conclude that the kinetically favourable product is the endo product. This is because the reaction barrier is smaller for the endo than for the exo reaction, meaning that the endo product is obtained the fastest. Favourable secondary orbital interactions in the endo case lower the energy of the TS and increase the rate of reaction. As can be seen in the diagram below, there is a bonding, through space interaction between the developing π bond at the back of the diene[6] and the two O atoms in the dienophile, which stabilises the TS. In the exo case, there is no possibility of secondary interactions, hence the reaction barrier is larger.

(I can see what you're showing, but don't change the overall colour of the orbitals without paying attention to the phases. Here you have no nodes between the p orbitals of the reactants Tam10 (talk) 15:16, 4 January 2017 (UTC))

Generally in DA reactions there is less steric hindrance in the exo adduct, which makes it the thermodynamic product. However in both the endo and exo adducts of this reaction, a two-carbon-atom bridge eclipses the dioxole ring. So sterically, there isn't a big difference between them. The tabulated results show that the reaction energy for the endo case is greater than for the exo case, i.e. the endo adduct is more thermodynamically stable than the exo adduct. Therefore we can conclude that in this reaction, the endo product is the kinetic as well as the thermodynamic product.

This was a good section, nice use iof Jmols, your energies are slightly out but you have still come to the correct conclusion. some understanding if it was inverse or normal would have been good.

Exercise 3: o-Xylene + SO2 Cycloaddition: Diels Alder vs Cheletropic Reactions

Reaction Scheme

As mentioned in the introduction, this exercise investigates another type of cycloaddition called a cheletropic reaction. The main difference between DA and cheletropic reactions is that in the latter, both new bonds are formed to a single atom[6] (in this case the sulfur atom).

The methodology for this exercise was different to that for the first two exercises. I started by drawing and optimising the product molecules, then working backwards to the TSs and reactants. Similarly to Exercise 1, the reactants, TSs and products were optimised at the PM6 level. The endo TS had one imaginary vibration at -334.01cm-1, the exo TS had one imaginary vibration at -333.77cm-1, and the cheletropic TS had one imaginary vibration at -486.67cm-1.

IRC

Below are the IRC animations for each of the three reactions. The animations clearly show that all three reactions proceed in a concerted manner with synchronous bond formation. They also illustrate the main driving force of reaction: the xylene 6-membered ring aromatises during the course of the reaction.

| Exo DA | Endo DA | Cheletropic |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(Your endo and exo are the same - both are endo Tam10 (talk) 15:16, 4 January 2017 (UTC))

Thermodynamic data

The reaction barriers and reaction energies for the three reactions were calculated in order to determine the kinetic and thermodynamic products. The reactant and product structures were taken from the end-points of each IRC, and were then minimised. These minimised structures gave the reactant and product energies included in the table below.

| Reactants | Transition State | Products | Reaction barrier | Reaction energy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endo DA | 178.3685935 | 237.7653 | 56.97598 | 59.3966865 | -121.393 |

| Exo DA | 178.344964 | 237.7679 | 56.98648 | 59.4229415 | -121.358 |

| Cheletropic | 186.3658665 | 260.0873 | -0.00525 | 73.7214145 | -186.371 |

The reaction profile diagram makes the tabulated results easier to interpret:

File:Pvy714 exercise 3 Reaction profile.pdf

The thermochemistry of the endo- and exo-DA is very similar; the two lines overlap in the reaction profile above. Similarly to Exercise 2, the endo adduct is the kinetic product out of the three reactions because it has the lowest reaction barrier. This again can be attributed to secondary orbital interactions which are not possible in the exo-DA and cheletropic reactions (see Exercise 2). The cheletropic path has the greatest reaction energy and it gives the most thermodynamically stable product. The reason for the greater stability of the cheletropic product could be the planar, five-membered heterocyclic adduct. In the DA-reactions, the six-membered heterocyclic adduct is more strained and thus less stable.

(Differences of ~0.01 kj/mol are negligible Tam10 (talk) 15:16, 4 January 2017 (UTC))

Referencing

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 E. Lewars, Computational Chemistry, 2010, 9-43.

- ↑ 2.K. Ramachandran, G. Deepa and K. Namboori, Computational chemistry and molecular modeling, Springer, Berlin, 1st edn., 2008.

- ↑ J. Kuriyan, B. Konforti and D. Wemmer, The molecules of life, Garland Science, 1st edn., 2013.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 T. Sorrell, Organic chemistry, University Science Books, Sausalito, 1st edn., 2010.

- ↑ H. Bent, Molecules and the chemical bond, Trafford Pub., [Bloomington, IN], 1st edn., 2011.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Clayden, Jonathan. Organic Chemistry. 1st ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001. Print..

- ↑ Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diels%E2%80%93Alder_reaction, (accessed December 2016)