Rep:Mod:PP1C

Conformational Analysis using Molecular Mechanics

Part One

The hydrogenation of cyclopentadiene dimer

.

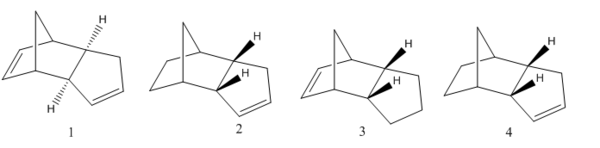

For this section a combination of ChemDraw and Avogadro programmes were used. Dimers 1 and 2 were each drawn in ChemDraw and saved as .cml files. They were then opened in Avogadro, protons added, and the geometries optimised under MMFF94s force field with 500 steps. The results are summarised below: Dimer 1 Dimer 2

| Dimer 1 | ' |

| Energies | Energies (kcal/mol) |

| Total bond stretching energy | 3.54275 |

| Total angle bending energy | 30.77122 |

| Total stretch bending energy | -2.04159 |

| Total torsional energy | -2.72089 |

| Total out of plane bending energy | 0.0148 |

| Total electrostatic energy | 13.01357 |

| Total van der waals | 12.79431 |

| Dimer 2 | ' |

| Energies | Energies (kcal/mol) |

| Total bond stretching energy | 3.46733 |

| Total angle bending energy | 33.19295 |

| Total stretch bending energy | -2.08208 |

| Total torsional energy | -2.94861 |

| Total out of plane bending energy | 0.02194 |

| Total van der waals | 12.35613 |

| Total electrostatic energy | 14.18308 |

Dimer 1 has the lowest energy after optimization concluding it is the thermodynamic product out of the two dimers. It also appears to be less strained and hindered as the protons are facing down away from the bridgehead carbon. Comparing individual energies, the stretch bond energy is 0.07542 kcal/mol higher in the thermodynamic product and the total stretch bending, torsional and van der waals energies are also higher in the thermodynamic product. However the energies of total angle bending, out of plane bending and electrostatic energies are all lower in dimer 1 suggesting less repulsion and strain in the structure. This results in dimer 1 having an energy 2.81709 kcal/mol lower in energy than dimer 2 with the total angle bending energy varying the most between the two conformers. Dimer 1 is the thermodynamic product, whilst endo dimer 2 is the kinetic product of the dimerisation of cyclopentadiene reaction. The kinetic endo product dominates in the reaction: as it is higher in energy it is the fastest forming product with a larger contribution of energy from electrostatic interactions and bond stretching. Therefore, the dimerisation of cyclopentadiene is kinetically controlled with the endo dimer 2 being the dominating product as it is higher in energy.

Similarly, for products 3 and 4, the same procedures were repeated and the results are summarised below: Hydrogenated Dimer 3 Hydrogenated Dimer 4

| Dimer 3 | ' |

| Energies | Energies (kcal/mol) |

| Total bond stretching energy | 3.30466 |

| Total angle bending energy | 31.86162 |

| Total stretch bending energy | -2.07695 |

| Total torsional energy | -1.27466 |

| Total out of plane bending energy | 0.01425 |

| Total van der waals | 13.69667 |

| Total electrostatic energy | 5.11913 |

| Dimer 4 | ' |

| Energies | Energies (kcal/mol) |

| Total bond stretching energy | 2.81065 |

| Total angle bending energy | 26.06312 |

| Total stretch bending energy | -1.6766 |

| Total torsional energy | -0.62595 |

| Total out of plane bending energy | 0.00377 |

| Total van der waals | 10.04754 |

| Total electrostatic energy | 5.14762 |

Summary of energies:

| Structure | Energy (kcal/mol) |

| Exo Dimer | 55.37417 |

| Endo Dimer | 58.19126 |

| Dihydro derivative 3 | 50.64471 |

| Dihydro derivative 4 | 41.77015 |

The hydrogenated dimers give energies of 50.64471 kcal/mol (structure 3) and 41.77015 kcal/mol (structure 4). Therefore, structure three is the kinetic product of the reaction whilst structure four is the thermodynamic product. Comparing individual energies, bond stretching, angle bending, out of plane bending and van der waals energies are all lower in the thermodynamic dimer whilst stretch bending, torsional and electrostatic energies are higher. Angle bending and van der waals energies are much lower in the thermodynamic dimer and are the two major contributors for the thermodynamic product being 8.87456 kcal/mol lower in energy. Hydrogenated dimer four experiences less strain from angle bending and less repulsive van der waals interactions which result in a more stable molecule.

From the hydrogenated dimer energies, it can be concluded that hydrogenation of the double bond closest to the bridgehead carbon occurs with less ease than hydrogenation of the double bond furthest from the bridgehead carbon, which occurs with greater ease. As hydrogenated dimer 3 is the kinetic product from the hydrogenation of dimer 2, the reaction proceeds through a lower energy transition state as it is easier to hydrogenate this double bond.

Atropisomerism of Intermediates involved in the synthesis of Taxol

.

Usually, in camphane and pinane systems, alkenes in bridgehead positions are not favored due to the large amount of strain imposed on the molecule. Bredts rule states that olefins avoid ring junctions as a result of strain however, in larger bicyclic ring systems hyper stable alkenes have been observed. These are systems that have negative strain energies:the difference in energy between the strain of the olefin and the strain in the parent hydrocarbon is negative resulting in more stable and less reactive alkenes. The alkenes in bridgehead positions react slowly, as the transition state is high in energy and therefore, there is a large activation energy to overcome for the reaction.[1] [2] During electrophyllic addition, a carbocation has to form and the most substituted is favored as there is most overlap and thus stabilisation between the empty p orbital and the C-H sigma bonds. In the Taxol intermediate, a stable tertiary carbocation can form however, it is much higher in energy because the bicylic structure prevents the transition state from adopting the required planar arrangement. Hence, the activation energy is higher so a larger energy barrier has to be overcome and the alkene reacts more slowly than alkenes with tertiary planar carbocation transition states.[3]

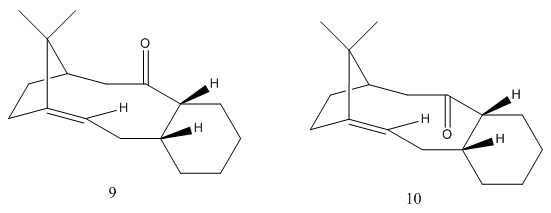

Using a combination of ChemDraw/ChemDraw Bio3D, the intermediates in Taxol synthesis, structures 9 and 10 were drawn and optimised. Since the cyclohexane ring can adopt four different conformations, two chairs and two twist boats, all were attempted to be found so that the lowest energy conformation of each intermediate could be determined.

The results of Taxol intermediates 9 and 10 are summarised below:

| Taxol (9) intermediate | ' | ' | ' |

| Conformation | Chair | Chair | Twist Boat |

| Energy (kcal/mol) | 47.8396 | 58.3857 | 53.0099 |

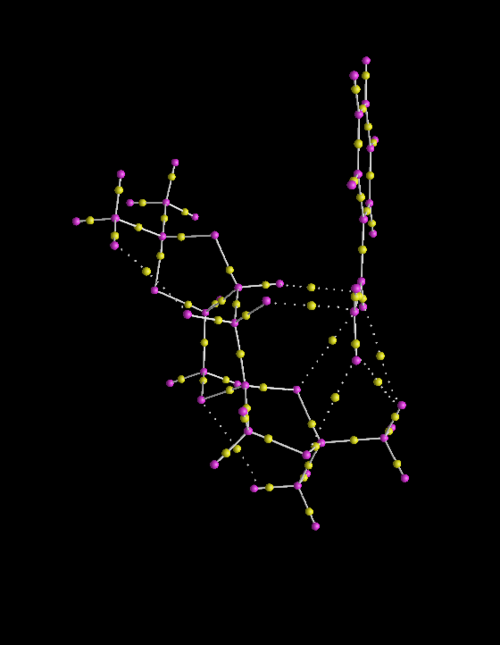

Intermidiate 9 Chair 1 Intermidiate 9 Chair 2 Intermidiate 9 twist boat1

| Taxol (10) intermidiate | ' | ' | ' |

| Conformation | Chair | Chair | Twist Boat |

| Energy (kcal/mol) | 42.6829 | 48.7374 | 53.6647 |

Intermidiate 10 Chair 1 Intermidiate 10 Chair 2 Intermidiate 10 twist boat

Both chair conformations were found however on drawing two different twist boats and optimising the geometries, the other twist boat conformation re-averted back to the twist boats above suggesting that the twist boat conformations found are the preferred lower energy conformations out of the two. For both isomers, the first chair conformation is the lowest in energy. On standing the isomer where the carbonyl is facing up isomerises to the isomer with the carbonyl facing down as it is the lowest energy conformation of all. Therefore, the Taxol atropisomer where the carbonyl is facing down and the cyclohexane ring adopts a chair conformation that gives an energy of 42.6829 kcal/mol, is the lowest energy and most stable atropisomer.

.

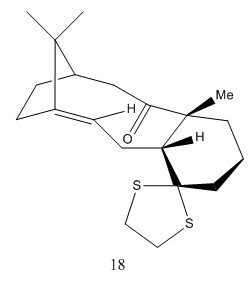

Structure 18 with cyclohexane in a boat conformation

Structure 18 with cyclohexane in a chair conformation with an energy of 100.63277 kcal/mol

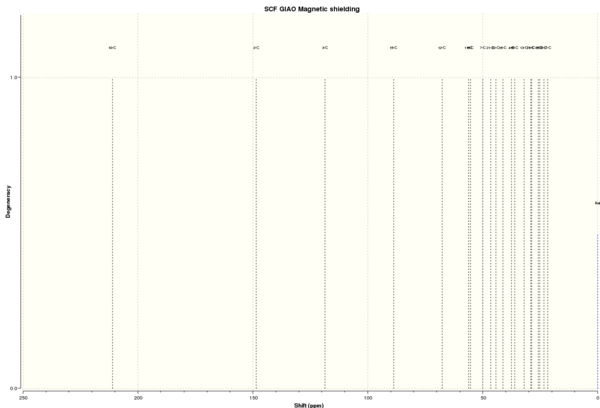

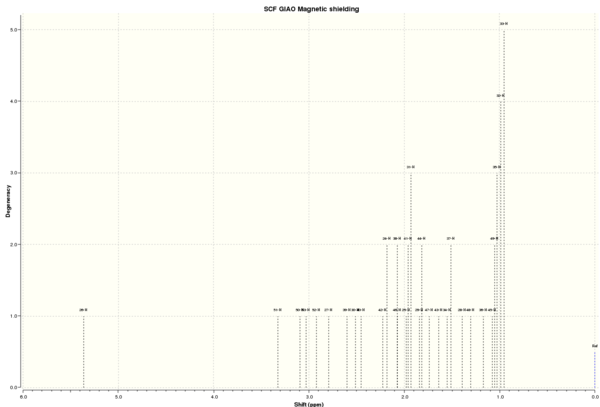

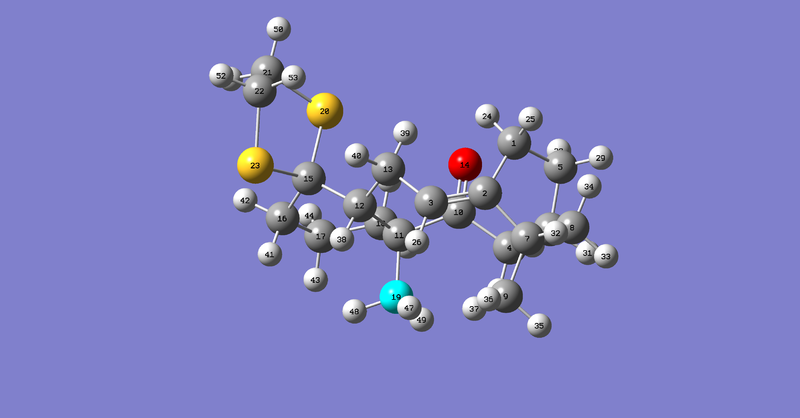

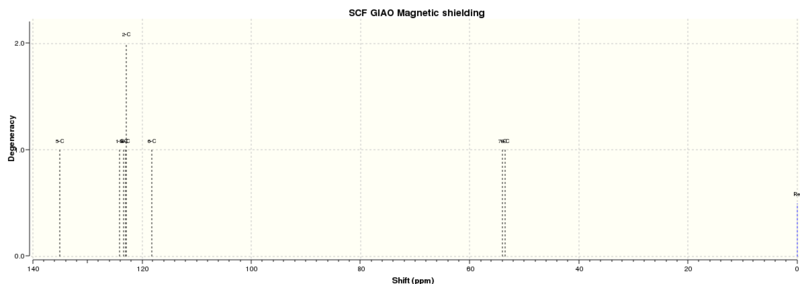

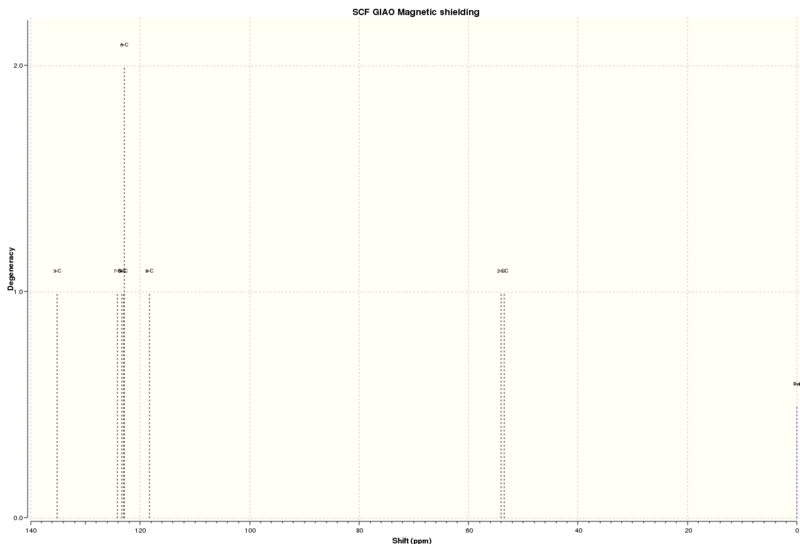

Having confirmed that in the Taxol intermediate where the carbonyl bond is facing down and the cyclohexane ring adopts a chair conformation is lowest in energy, molecule 18 was drawn and optimised ensuring it was in this conformation. The resulting structure was submitted for NMR on the HPC and the results are summarised below. Both 13C NMR and 1H NMR can be observed. DOI:10042/26420 The calculation was run using benzene as a reference, the same as the literature. This enabled comparisons to be made between computed values and experimental values.[4]On carbons bearing heavy atoms of oxygen or sulphur, a spin-orbit coupling correction was incorporated. For carbonyl carbons the following correction was applied: (0.96*chemical shift) + 12.2.

In order to determine the correction for carbons bearing sulphur atoms, a computational NMR of dimethyl sulphide (DMS) and methane in benzene as a reference was carried out. These molecules were chosen as there are the simplest molecules which would give a chemical shift for carbon bonded to sulphur. The difference in chemical shift between the DMS and methane was determined and this correction applied to carbons bearing sulphur atoms. The results before corrections and after corrections were applied can be viewed below.

| Taxol NMR before corrections applied | ' | ' | ' |

| Literature | Experimental | Difference in Chemical shift (ppm) | |

| Carbon number on gaussian | Carbon shifts (ppm) | Carbon shift (ppm) | |

| 17 | 19.83 | 21.69807681 | 1.868076812 |

| 9 | 21.39 | 23.27904206 | 1.88904206 |

| 5 | 22.21 | 25.10466657 | 2.894666572 |

| 8 | 25.35 | 25.85189365 | 0.501893654 |

| 1 | 25.56 | 28.61943291 | 3.059432908 |

| 19 | 30 | 29.09114849 | -0.908851511 |

| 13 | 30.84 | 31.98750987 | 1.147509868 |

| 18 | 35.47 | 36.15917692 | 0.689176919 |

| 4 | 36.78 | 37.44869609 | 0.668696087 |

| 16 | 38.73 | 41.24118297 | 2.511182967 |

| 22 | 40.82 | 44.29144608 | 3.471446084 |

| 21 | 43.28 | 46.58662471 | 3.306624705 |

| 7 | 45.53 | 49.9228641 | 4.392864102 |

| 6 | 50.94 | 55.40133961 | 4.461339615 |

| 11 | 51.3 | 56.074897 | 4.774896999 |

| 12 | 60.53 | 67.54300617 | 7.013006175 |

| 15 | 74.61 | 88.68066519 | 14.07066519 |

| 3 | 120.9 | 118.6191554 | -2.280844624 |

| 2 | 148.72 | 148.5738706 | -0.146129378 |

| 10 | 211.49 | 211.014449 | -0.475551011 |

.

Determining sulphur correction:

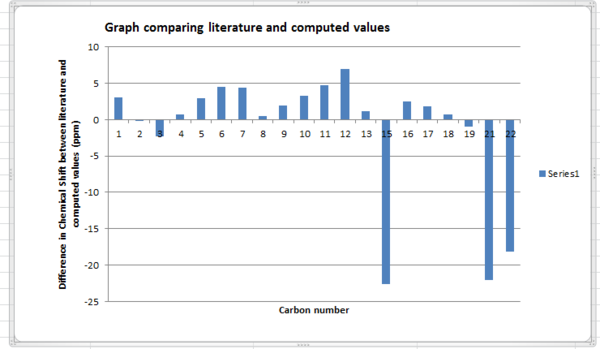

13C NMR for DMS and methane was used to determine the correction for sulphur. DMS had a carbon chemical shift of 21.5938616 ppm whilst, methane had a carbon chemical shift of -3.75994ppm. The difference was therefore 25.3538016 ppm. This correction was applied to carbon atoms 15,21 and 22. It should be noted that as carbon fifteen is bonded to two sulphur atoms the correction was multiplied by two and applied. Comparing the difference in chemical shifts between computed and literature values, there appears to be less of a difference in chemical shift when the corrections are not applied. On application of the corrections, the difference in chemical shifts, particularly for carbons bonded to sulphur increases in range.

The results are summarised below.

| After correction applied | ' | ' | ' | ' |

| Literature | Experimental | |||

| Carbon number | Carbon shifts (ppm) | Carbon shift (ppm) | Correction (ppm) | Difference in chemical shift (ppm) |

| 1 | 25.56 | 28.61943291 | 3.059432908 | |

| 2 | 148.72 | 148.5738706 | -0.146129378 | |

| 3 | 120.9 | 118.6191554 | -2.280844624 | |

| 4 | 36.78 | 37.44869609 | 0.668696087 | |

| 5 | 22.21 | 25.10466657 | 2.894666572 | |

| 6 | 50.94 | 55.40133961 | 4.461339615 | |

| 7 | 45.53 | 49.9228641 | 4.392864102 | |

| 8 | 25.35 | 25.85189365 | 0.501893654 | |

| 9 | 21.39 | 23.27904206 | 1.88904206 | |

| 10 | 211.49 | 211.014449 | 214.773871 | 3.283871 |

| 11 | 51.3 | 56.074897 | 4.774896999 | |

| 12 | 60.53 | 67.54300617 | 7.013006175 | |

| 13 | 30.84 | 31.98750987 | 1.147509868 | |

| 15 | 74.61 | 88.68066519 | 63.3268636 | -22.5662728 |

| 16 | 38.73 | 41.24118297 | 2.511182967 | |

| 17 | 19.83 | 21.69807681 | 1.868076812 | |

| 18 | 35.47 | 36.15917692 | 0.689176919 | |

| 19 | 30 | 29.09114849 | -0.908851511 | |

| 21 | 43.28 | 46.58662471 | 21.23282311 | -22.04717689 |

| 22 | 40.82 | 44.29144608 | 22.69758448 | -18.12241552 |

.

.

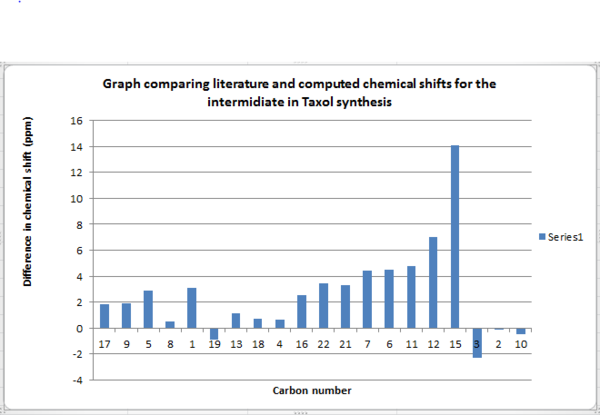

Graph comparison with literature and computed values having incorporated corrections.

Computer simulated NMR assumes the bonds in the molecule are frozen: there are no rotations about single bonds or vibrations. Experimentally the literature values [4] are averages as the molecule is rotating and vibrating, and since NMR is a relatively slow technique, it can take these motions into account and an ‘averaged’ spectrum is observed. It can therefore be expected that computed and literature values will differ. However on application of the corrections the difference between computed values and the literature are larger suggesting the structure of the molecule differs largely from the actual product. Before the corrections are applied the computed chemical shifts which deviate largely from the literature are positive. Carbons 12 and 15 show a difference of 7 and 14.1 ppm respectively, from literature. The bonds lengths to oxygen and sulphur could be shorter than the actual product, resulting in greater de-shielding and hence a larger chemical shift than expected.

Having included a frequency calculation in the running of the overall calculation, the log file could be opened and the sum of electronic and thermal energies determined. The sum of electronic and thermal free energies corresponds to the free energy change of the reaction. For intermediate 18 this was -1651.460603 a.u. In the next section the free energies of different isomers will be used to determine the equilibrium constant and enantiomeric excess of the reactions.

Part two

Crystal Structures of the Shi and Jacobsen asymmetric epoxidation catalysts

The Cambridge Crystal Data Centre was used to to search for the Shi and Jacobsen catalysts and then analysed using Mercury programme.

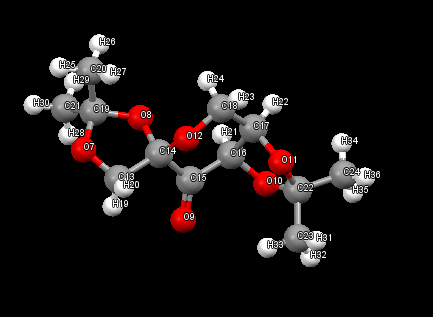

Shi Fructose Catalyst

Two hits were found on the CCDC for this structure. There are three anomeric centres present in the Shi catalyst crystal structure. The numbers on the atoms correspond to the labelled atoms on the diagram. For all three anomeric centres the individual bond lengths O-C-O fragments are different. The anomeric effect in this case is the interaction of donor oxygen lone pairs and the C-O sigma* anti-bonding orbitals which are in the right orientation, resulting in lengthening of the C-O bond. This causes one C-O bond on the O-C-O fragment to lengthen, and the other to shorter as electron density into anti-bonding orbitals weakens the bond thus lengthening it, whilst donation of lone pairs would shorten the 'donor' C-O bond. As a result of the anomeric effect, on each O-C-O fragment, one C-O bond is smaller and the other bond length larger than the average C-O bond length of 1.43A.[5]

The bond lengths of the anomeric centres are summarised below:

| O-C-O fragment | Bond Length (A) | Bond Angle |

| O7-C19-O8 | 1.3803 and 1.4433 | 105.3 |

| 08-C14-O12 | 1.3902 and 1.4083 | 112.5 |

| O10-C22-O11 | 1.4383 And 1.4163 | 105.1 |

.

NELQUEA

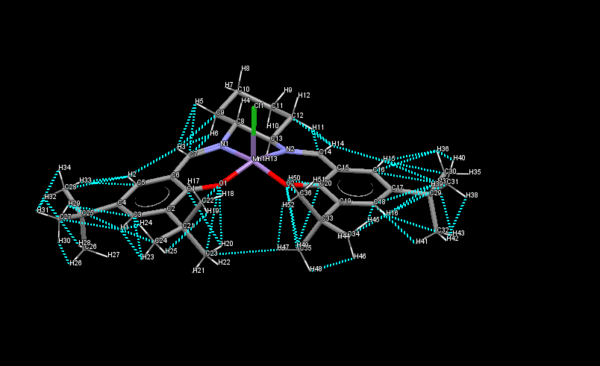

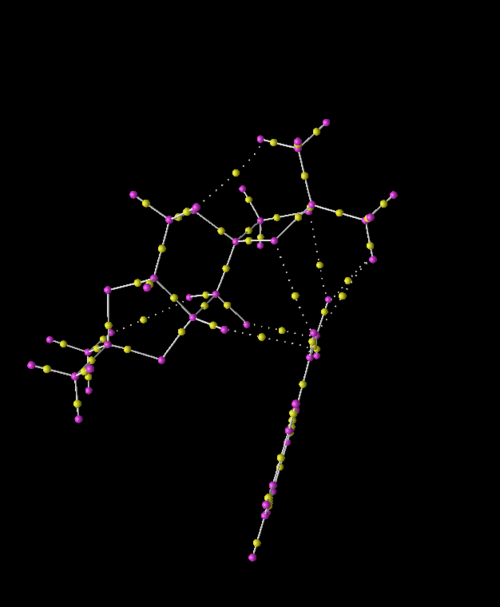

Jacobsen Epoxidation Catalyst

.

TOVNIBOV1

A short contact is an intramolecular contact where the distance between the two atoms is less than the sum of the van der Waals radii. In the case of the Jacobsen catalyst, the blue dashed lines in the diagram show all the short contacts present in the structure. The shortest contact between the two adjacent tertiary butyl groups is between C and H with a distance of 2.985A.On the diagram this is Carbon 23 and H 47. Studying the structure of the molecule, it is more planar compared to the Shi catalyst, reflecting the idea that the cis alkene is reacted with this catalyst. The chlorine atom bound to manganese appears to be perpendicular at least to the ligands co-ordinating off the rest of the manganese atom. The bulky tertiary butyl groups appear to cause loss of overall perfect planarity of the molecule.

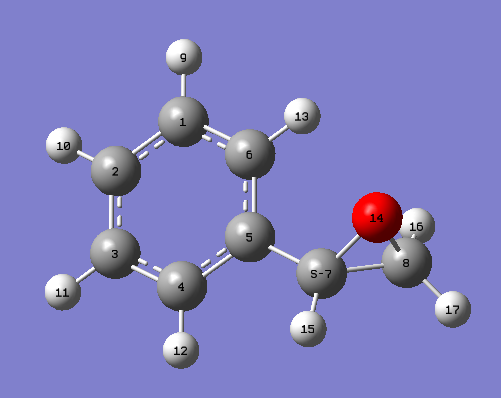

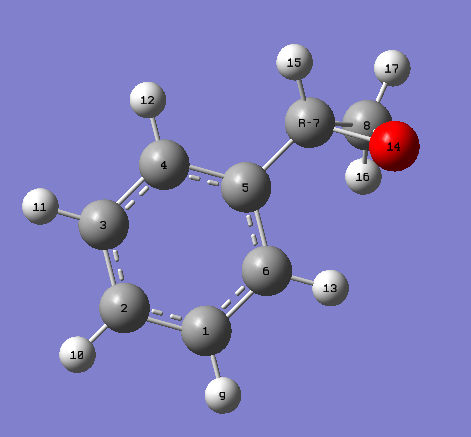

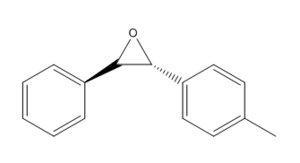

Calculated NMR properties of products

The two epoxides chosen were styrene epoxide and beta methyl styrene epoxide. This section predicts the absolute configuration of the two epoxides. These results will then be compared to results obtained during the actual synthesis. Firstly, the two different configurational isomers of each epoxide were drawn and optimised. The results are summarised below.

(R/S) Styrene epoxide Configuration Data

(R)-Styrene epoxide

| Energy (kcal/mol) | Energy (kcal/mol) |

| Total electrostatic energy | 3.07324 |

| Total Van der Waals energy | 13.67414 |

| Total out of plane bending energy | 0.00164 |

| Total torsional energy | 2.34618 |

| Total stretch bending energy | -0.74668 |

| Total angle bending energy | 1.42463 |

| Total bond stretching energy | 1.84192 |

| Total energy | 21.61507 |

(S)-Styrene epoxide

| Energy (kcal/mol) | Energy (kcal/mol) |

| Total electrostatic energy | 3.07777 |

| Total Van der Waals energy | 13.66999 |

| Total out of plane bending energy | 0.00167 |

| Total torsional energy | 2.34615 |

| Total stretch bending energy | -0.74646 |

| Total angle bending energy | 1.42453 |

| Total bond stretching energy | 1.84139 |

| Total energy | 21.61505 |

The lowest energy configuration is S-styrene epoxide.

Beta methyl styrene epoxide configuration data

(S,S)-Beta methyl styrene epoxide configuration)

| Energy (kcal/mol) | Energy (kcal/mol) |

| Total electrostatic energy | 3.04461 |

| Total Van der Waals energy | 14.32093 |

| Total out of plane bending energy | 0.00165 |

| Total torsional energy | 2.89572 |

| Total stretch bending energy | -0.76398 |

| Total angle bending energy | 1.73558 |

| Total bond stretching energy | 1.88594 |

| Total energy | 23.12046 |

(R,R)-Beta methyl styrene epoxide

| Energy (kcal/mol) | Energy (kcal/mol) |

| Total electrostatic energy | 3.0388 |

| Total Van der Waals energy | 14.32575 |

| Total out of plane bending energy | 0.00161 |

| Total torsional energy | 2.89544 |

| Total stretch bending energy | -0.76428 |

| Total angle bending energy | 1.73662 |

| Total energy | 23.12031 |

The lowest energy configuration is R,R beta methyl styrene epoxide.

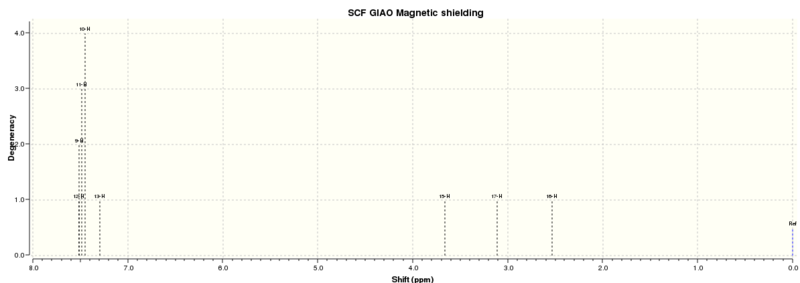

Having identified the lowest energy isomers, NMR, Coupling, Optical rotation, VCD and ECD calculations were carried out. In order to prove that the other isomers were indeed the other configuration, the optical rotation of the other higher energy isomers were also calculated.

Styrene

(S)-Styrene

.

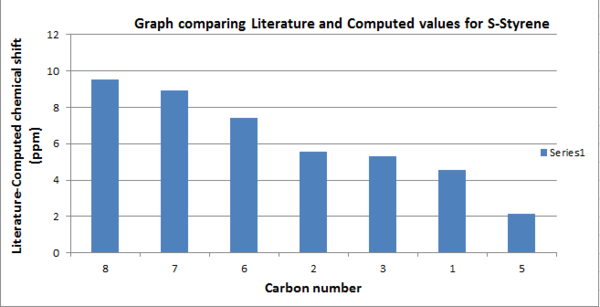

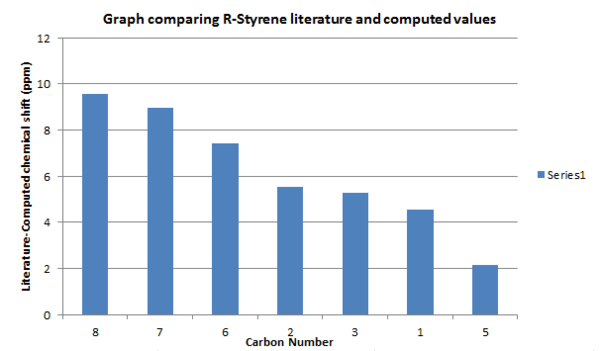

The 13C NMR was compared to the literature in order to check that the core structure of the product was correct.[6]

| Carbon number | Computed chemical shift (ppm) | Literature chemical shift (ppm) | Difference (ppm) |

| 8 | 53.4557 | 63 | 9.5443 |

| 7 | 54.0506 | 63 | 8.9494 |

| 6 | 118.268 | 125.7 | 7.432 |

| 2 | 122.953 | 128.5 | 5.547 |

| 3 | 123.415 | 128.7 | 5.285 |

| 1 | 124.133 | 128.7 | 4.567 |

| 5 | 135.134 | 137.3 | 2.166 |

.

Looking at the graph carbons 7 and 8 deviate most from the literature, and the computed chemical shifts are smaller than the literature values. This suggests that the bonds in the computed structure could be longer than the actual product and are therefore more shielded and, as a result have lower chemical shifts. Also, these carbons are both bonded to oxygen, a heavy atom, therefore deviation from literature is to be expected. As mentioned in the Taxol intermediate section, deviation also results as the molecule is static whereas in nature, rotation and vibration of bonds cause an average spectrum to be observed.

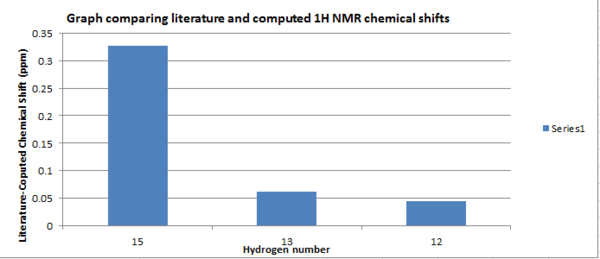

In using NMR to prove the integrity of the computed structure, 13C NMR is far more appropriate to use as the carbons atoms form the core structure of the molecule. The 1H NMR will be compared however, the spectrum alone cannot be used to check that the correct structure has been obtained since it does not form the framework of the molecule. For S-Styrene in the literature[6]the chemical shifts appear as ranges, whilst the computed spectrum gives individual shifts. Therefore, the maximum and minimum of the chemical shift range will be compared to the corresponding chemical shift values only. The results are summarised below:

| Carbon Number | Computed chemical shift (ppm) | Literature chemical shift (ppm) |

| 16,17,15 | 2.53-3.66246 | 3.99 |

| 13,10,11,9,12 | 7.2978-7.51459 | 7.56-7.36 |

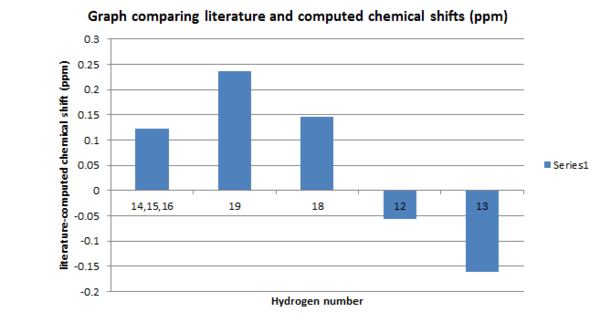

Table of data used for graph comparison:

| Carbon Number | Computed chemical shift (ppm) | Literature chemical shift (ppm) | Difference in chemical shift (ppm) |

| 15 | 3.66246 | 3.99 | 0.32754 |

| 13 | 7.2978 | 7.36 | 0.0622 |

| 12 | 7.51459 | 7.56 | 0.04541 |

.

Similarly to the 13C NMR, literature values are higher however, there appears to be far less deviation from the literature with the maximum being 0.32754 ppm. The protons that have been assigned are in good agreement with the literature, however, this spectrum is far less useful in determining whether the core structure is correct. Coupled with the 13C NMR data analysis it can be concluded that the core structure is different in terms of the bond lengths, particularly the bond lengths between carbon and heavy atoms. The computed values assume the bond lengths are longer, resulting in lower chemical shifts.

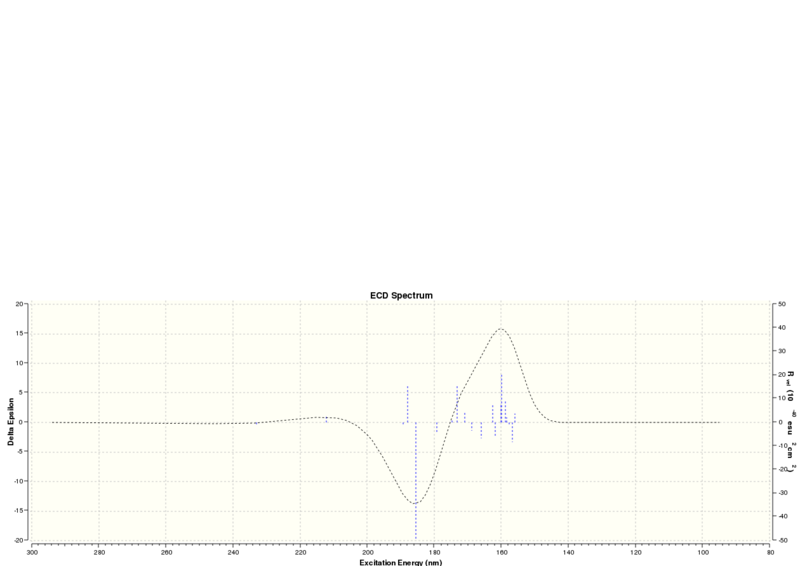

Having compared the S-Styrene structure to the literature, subsequent calculations were run. The optical rotation, VCD and ECD data is shown below.

Optical Rotation:

The S-Styrene optical rotation was computed to be [Alpha] ( 5890.0 A) = +30.08 deg. DOI:10042/26435 In order to prove that the other isomer was indeed the other configuration, an optical rotation on that isomer was also run. For R-Styrene a result of [Alpha] ( 5890.0 A) = -30.02 deg was obtained. DOI:10042/26425

| Isomer | Optical Rotation (deg) |

| S-Styrene | 30.08 |

| R-Styrene | -30.02 |

Table of results for optical rotation

These values are almost the complete opposite, different in sign and by a difference of 0.06 deg. The optical rotation for S-Styrene is in accordance to the literature[7]:

| ' | Literature opitcal rotation (deg) | Computed optical rotation (deg) |

| S-Styrene | 32.1 | 30.08 |

The optical rotation is lower by 2.02 deg, giving a relative error of -6%. It would be expected that the computed value is different from the literature: Firstly, from NMR analysis it has been confirmed that the computed structure is different to the molecule found in nature, so the optical rotation is likely to differ and secondly, since the optical rotation value is less than 50, this calculation method is highly sensitive to small changes in conformation. Furthermore, no temperature was input for the computed spectrum so it is not possible to know what temperature the calculation was run at. This is likely to cause deviations in the optical rotations. Finally, experimentally, within the solution there are interactions of the molecule with the solvent and with each other and in the computed spectrum, whilst the solvent is accounted for, if interactions with other molecules of itself are not, then small structural changes in the molecule are not accounted for and the optical rotation differs.

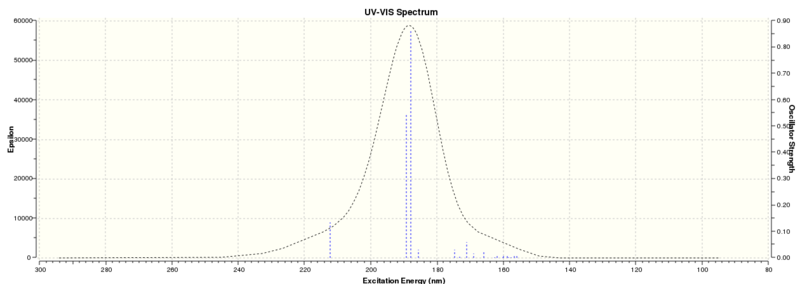

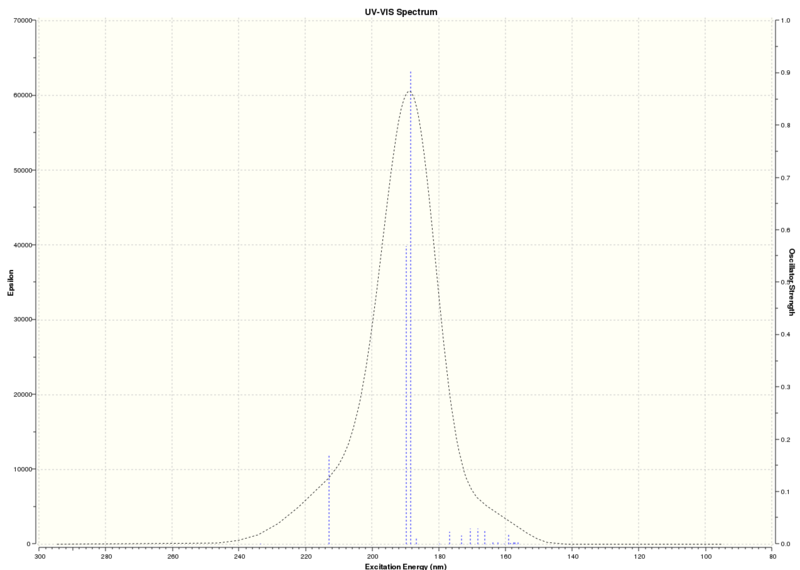

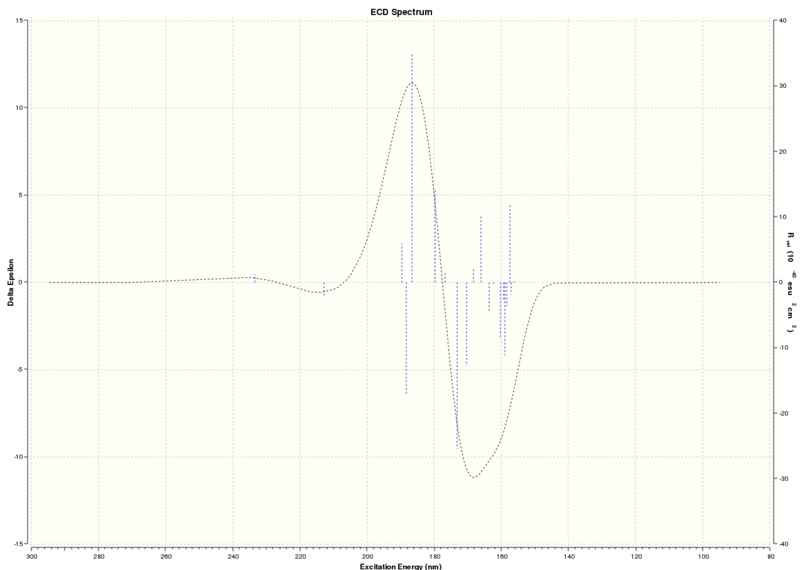

Vibrational circular dichroism (VCD)and Electronic circular dichroism (ECD) calculations were also run and can be viewed below. These are less sensitive towards conformations and so are likely to give reliable results for absolute configuration for small optical rotation results. However, since these techniques are not available in the lab, the computed optical rotations will be compared to those obtained from synthesis.

| Technique | Wavelength (nm) |

| UV-Vis | 187.98 |

| ECD | 185.54 and 159.82 |

Surveying the wavelengths obtained, it can be concluded that there are no chromophores that absorb in the UV/Visible region, the wavelengths found are too low and so no further chiroptical property can be obtained from this.

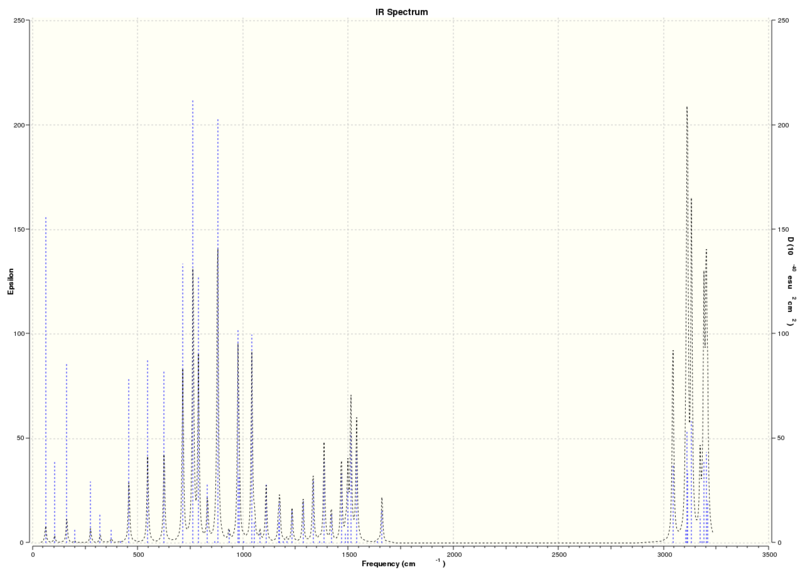

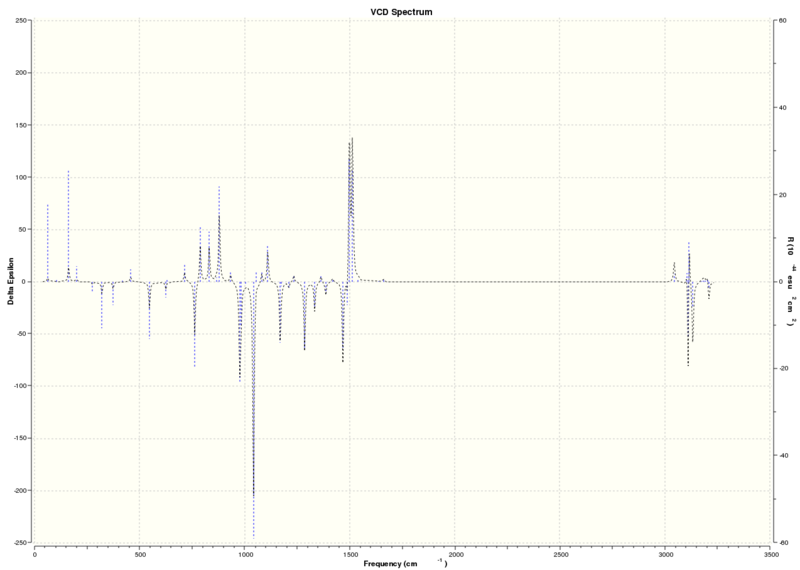

VCD and Absolute Configuration

The IR and VCD spectra can be viewed above. Ideally in order to determine the absolute configuration of the molecule, these computed IR and VCD results would be compared to the experimentally obtained spectra. If the assignments for a particular configurations are in agreement to each other, then from the signs of the VCD spectrum, the absolute configuration can be established. If the signs of the computed and experimentally determined VCD are different, then the absolute configuration of the molecule is the opposite to the calculated one.[10] Since VCD is not available in the laboratory, the computed values will not be compared to experimental data. S-Styrene NMR and Frequency data: DOI:10042/26421 S-Styrene Coupling constants: DOI:10042/26422 S-Styrene ECD: DOI:10042/26423

R (NMR) Styrene

.

Table comparing R-Styrene epoxide 13C NMR with literature:

| Carbon number | Computed chemical shift (ppm) | Literature chemical shift (ppm) | Difference in Chemical shift (ppm) |

| 8 | 53.4573 | 63 | 9.5427 |

| 7 | 54.05 | 63 | 8.95 |

| 6 | 118.268 | 125.7 | 7.432 |

| 2 | 122.954 | 128.5 | 5.546 |

| 3 | 123.415 | 128.7 | 5.285 |

| 1 | 124.132 | 128.7 | 4.568 |

| 5 | 135.133 | 137.3 | 2.167 |

.

This confirms that the NMR spectrum is not affected by differing conformations: the difference in chemical shift between R and S configurations is negligible.

NMR and frequency calculations for R-Styrene: DOI:10042/26424

(R,R)-beta methyl styrene epoxide

The lowest energy isomer of beta methyl styrene was the R,R configuration. The 13C and 1H NMR will now be compared to the literature of this enantiomer.[6]

Table comparing literature and computed chemical shifts:

| Carbon number | Computed chemical shift (ppm) | Literature chemical shift (ppm) | Difference in chemical shift (ppm) |

| 9 | 18.8377 | 26 | 7.1623 |

| 7 | 60.576 | 51.3 | -9.276 |

| 8 | 62.3197 | 59.3 | -3.0197 |

| 4 | 118.486 | 127.8 | 9.314 |

| 2 | 122.727 | 127.8 | 5.073 |

| 6 | 122.796 | 128.8 | 6.004 |

| 1 | 123.328 | 128.8 | 5.472 |

| 3 | 124.072 | 128.9 | 4.828 |

| 5 | 134.975 | 140.7 | 5.725 |

.

.

Carbons 7 and 4 shows greatest deviation from the literature, with Carbon 7 being 9.276 ppm larger, and carbon 4 being 9.314 ppm smaller than the literature values. Carbon 7 is bonded to the heavy oxygen atoms so is likely to experience a greater deviation. The bond length between C-O may be shorter than the literature whilst the C-C bond in the aromatic ring could be longer than in nature, hence difference chemical shifts are observed due to the distance from other atoms. This is a possible explanation for the difference in chemical shift.

The assignment of the proton NMR is tabulated below:

| Hydrogen number | Computed chemical shift (ppm) |

| 14 | 0.716945 |

| 15 | 1.5873 |

| 16 | 1.67823 |

| 19 | 2.78786 |

| 18 | 3.41466 |

| 12 | 7.30727 |

| 10 | 7.4215 |

| 20 | 7.4764 |

| 11 | 7.49653 |

| 13 | 7.50058 |

This data will now be compared to the literature, however since the literature gives a range only the protons corresponding to the maximum and minimum are compared.[6] Other chemical shifts have been averaged. The results are shown below:

Table of results:

| Hydrogen number | Computed chemical shift (ppm) | Literature chemical shift (ppm) | Difference in chemical shift (ppm) |

| 14,15,16 | 1.327491667 | 1.45 | 0.122508333 |

| 19 | 2.78786 | 3.025 | 0.23714 |

| 18 | 3.41466 | 3.56 | 0.14534 |

| 12 | 7.30727 | 7.25 | -0.05727 |

| 13 | 7.50058 | 7.34 | -0.16058 |

.

All differences in the proton NMR are below one and positive: the literature chemical shifts for protons that can be compared are larger. The bond lengths of the naturally occurring enantiomer could be shorter than the computed molecule. As before, the proton spectrum alone cannot allow one to determine the accuracy of the molecule compared to nature because the protons do not form the core structure of the molecule. NMR and frequency calculation: DOI:10042/26426 Coupling calculation: DOI:10042/26427

Optical rotation

An optical rotation calculation was run on the lowest energy enantiomer and the following result was obtained: [Alpha] ( 5890.0 A) = 46.77 deg. DOI:10042/26428 In order to prove that the other isomer was indeed the opposite configuration (S,S)-beta methyl styrene, an optical rotation calculation on this molecule was also run and the following result obtained: [Alpha] ( 5890.0 A) = -46.77 deg. DOI:10042/26429 This is the exact opposite of the other isomer, proving that two different configurations have been found. These values will be compared to the optical rotation values obtained during the synthesis part of the experiment.

| Isomer | Optical rotation (deg) |

| R,R Isomer | 46.77 |

| S,S Isomer | -46.77 |

Table summarising optical rotations obtained for the epoxide of beta methyl styrene.

Since these optical rotation values are below 50 deg, they are sensitive to changes in conformation and so ECD and VCD calculations were performed on (R,R)- beta methyl styrene which are more accurate for molecules with low value optical rotations. It should be noted that these techniques will not be compared to the experimental optical rotations because the equipment is not available in the lab.

The results from the optical rotation calculation will now be compared to the literature[7]:

| ' | Literature optical rotation (deg) | Computed optical rotation (deg) |

| R,R beta methyl styrene | 47.2 | 46.77 |

The literature optical rotation is 0.43 deg higher than the computed optical rotation with a relative error of -0.91%. This is likely to arise as a result of small differences in conformation between the two molecules. Further sources of error could be due to interaction between the same molecules not being accounted for and the temperature not being defined for the computed structure.

UV/Vis and ECD spectra DOI:10042/26430

| Technique | Wavelength (nm) |

| UV/Vis | 188.4 nm |

| ECD | 186.65 nm |

Table summarising results from UV/Visible spectrum and ECD spectrum

The absorptions are outside the range of UV/Visible light, therefore no chromophore exists that will absorb in the UV/Visible region, hence no further information can be gained on chiroptical properties of the beta methyl styrene epoxide.

IR and VCD spectra

The IR and VCD calculations are more reliable methods of determining the absolute configurations as they are less sensitive to small changes in conformation however, it will not be possible to compare this to experimental values as the equipment is not available in the lab.

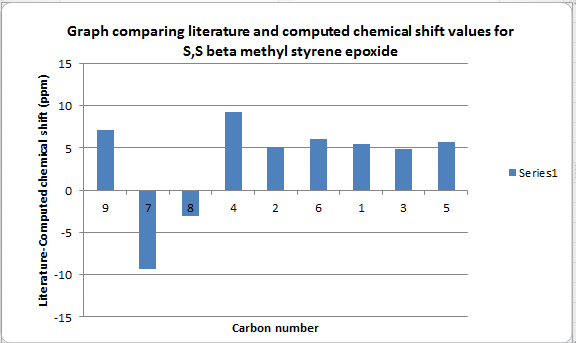

S,S beta methyl styrene

Table summarising S,S beta methyl styrene epoxide data with literature[6]

| Carbon number | Computed chemical shift (ppm) | Literature chemical shift (ppm) | Difference in Chemical shift (ppm) |

| 9 | 18.8377 | 26 | 7.1623 |

| 7 | 60.576 | 51.3 | -9.276 |

| 8 | 62.3196 | 59.3 | -3.0196 |

| 4 | 118.486 | 127.8 | 9.314 |

| 2 | 122.727 | 127.8 | 5.073 |

| 6 | 122.796 | 128.8 | 6.004 |

| 1 | 123.328 | 128.8 | 5.472 |

| 3 | 124.072 | 128.9 | 4.828 |

| 5 | 134.976 | 140.7 | 5.724 |

.

The difference in chemical shift between the R,R and S,S configurations is negligible and this is to be expected. S,S beta methyl styrene epoxide NMR: DOI:10042/26431 S,S beta methyl styrene epoxide Coupling: DOI:10042/26432

Enantiomeric Excess

The general procedure for determining the enantiomeric excess was as follows: An equilibrium was set up between the different transition state configurations for a given epoxide. The sum of electronic and thermal free energies from the log file were recorded for each transition state in order to then find the lowest energy transition state for each configuration in the molecule. The energy difference between the two configurations was then determined and the energy converted in to J/mol. Using, G= -RTlnK, where R = gas constant 8.314 JK-1mol-1, T = temperature, and K = equilibrium constant, the free energy change was determined. To determined the enantiomeric excess K = x/(1-x) where x = number of moles. 'X' was then made the subject of the equation such that x = K/(1+K) and then to determine the enantiomeric excess as a percentage the answer was multiplied by 100. Therefore ee (enantiomeric excess) = [ K/(1+K)] * 100 The equilibrium constant and enantiomeric excess for trans beta methyl styrene transition state from the Shi catalyst, cis beta methyl styrene transition state from the Jacobsen catalyst and Styrene transition state from the Shi catalyst were determined. The results are summarised below for each transition state and will be compared to experimental results in due course.

The highlighted row is the identified lowest energy transition state transformation.

Trans-Beta methyl styrene transition state from Shi catalyst

In the literature,the enantiomeric excess for (R,R)-trans beta methyl styrene epoxide is 99%.[7]This value is in line with the computed value of 99.97%.

S,S transition state --------> R,R transition state

| (S,S) Energy (a.u.): | (R,R) Energy (a.u.): | Free energy difference (a.u) |

| -1343.017942 | -1343.02297 | -0.005028 |

| -1343.015603 | -1343.019233 | -0.00363 |

| -1343.023766 | -1343.029272 | -0.005506 |

| -1343.024742 | -1343.032443 | -0.007701 |

Table to show energies of transition states

| (S,S) Energy (J/mol) | (R,R) Energy (J/mol) | Free energy difference (J/mol) | K | Enantiomeric Excess (%) |

| -3526111729 | -3526131948 | -20218.977 | 3500.996761 | 99.97144486 |

Table summarising energies, K, and enantiomeric excess

Cis beta methyl styrene transition state from Jacobsem Catalyst

R,S transition state ----------> S,R

| Energy (R,S) (a.u) | Energy (S,R) (a.u) | Free energy difference (a.u) |

| -3383.25106 | -3383.259559 | -0.008499 |

| -3383.25027 | -3383.253442 | -0.003172 |

Table to show energies of transition states

| (R,S) Energy (J/mol) | (S,R) Energy (J/mol) | Free energy difference (J/mol) | K | Enantiomeric Excess (%) |

| -8882726335 | -8882748649 | -22314.126 | 8155.510035 | 99.98773985 |

Table summarising energies, K, and enantiomeric excess

Styrene epoxide transition state from Shi Epoxidation catalyst

R transition state ----------> S transition state

| ( R) Styrene Transition state Energy (a.u.) | (S) Styrene Transition State Energy (a.u) | Free energy Difference (a.u.) |

| -1303.730703 | -1303.733828 | -0.003125 |

| -1303.730238 | -1303.724178 | 0.00606 |

| -1303.736813 | -1303.727673 | 0.00914 |

| -1303.738044 | -1303.738503 | -0.000459 |

Table to show energies of transition states

| R- styrene TS Energy (J/mol) | S-Styrene TS Energy (J/mol) | Free energy difference (J/mol) | K | Enantiomeric Excess (%) |

| -3422964495 | -3422965700 | -1205.104 | 1.626458967 | 61.92592336 |

Table summarising energies, K, and enantiomeric excess

The enantiomeric excess was determined to be 61.9%. This is in accordance to the literature range of 60-75% and will be compared to the enantiomeric excess from the synthesis part of the experiment in the future.[8]

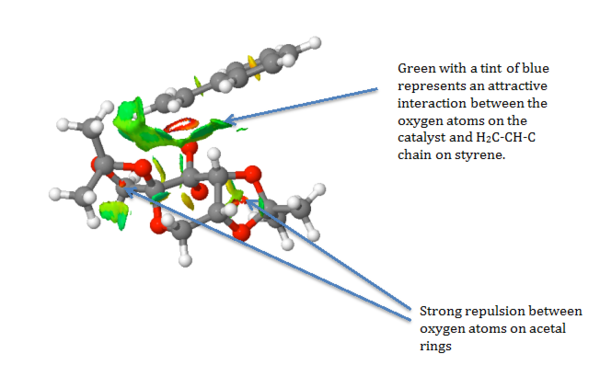

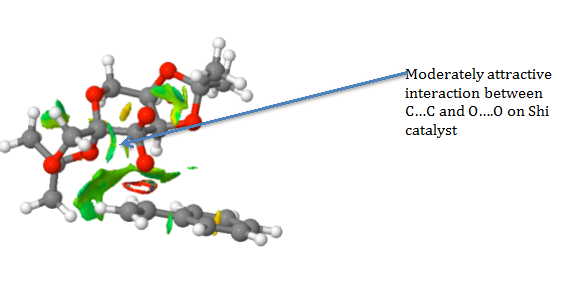

Non-Covalent Interactions Analysis on S-Styrene and Shi Catalyst Transition State

The lowest energy transition state of the Shi epoxidation of Styrene was subjected to a non-covalent interactions analysis (NCI). From the log files, the lowest free energy of each transition state was determined and the respective energies are summarised below.

| S-Styrene and Shi catalyst Transtion state (a.u) | R-Styrene and Shi catalyst transiton state (a.u) |

| -1303.733828 | -1303.730703 |

| -1303.724178 | -1303.730238 |

| -1303.727673 | -1303.736813 |

| -1303.738503 | -1303.738044 |

Table summarising energies of the transition states between Styrene and the Shi Catalyst.

The lowest energy transition state was subjected to NCI analysis as being the lowest in energy, it is the most accurate representation of the transition state and interactions between the styrene and Shi catalyst can give insight into how the stereo-chemistry of the molecule arises. The lowest energy of -1303.738503 a.u corresponded to an S-Styrene and Shi catalyst transition state.

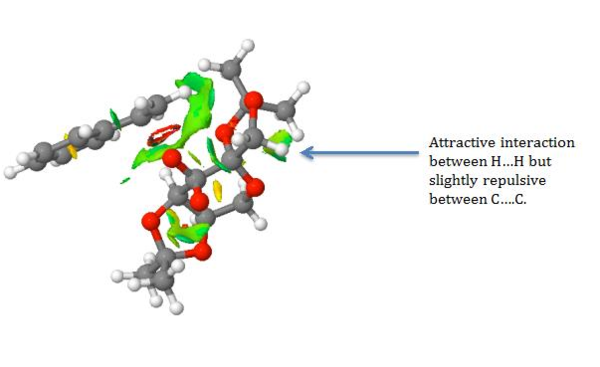

The NCI showed predominately a mild attractive interaction between the hydrocarbon chain bonded to the benzene ring on styrene and the oxygen atoms on one of the acetal rings and one oxygen on the dioxygen ring of the Shi catalyst. The attractive and repulsive interactions will orientate the molecule of styrene and the Shi Catalyst thus influencing the stereo-chemistry of the product. No hydrogen bonding is observed as there are no hydrogen atoms bonded to electronegative atoms such as oxygen that can interact with other oxygen lone pairs. The interactions are also summarised in the screenshots below.

.

.

.

.

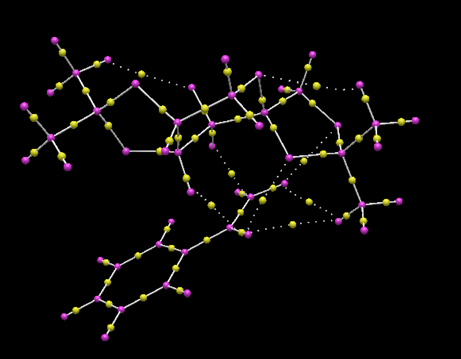

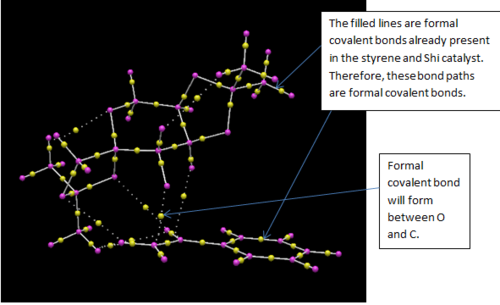

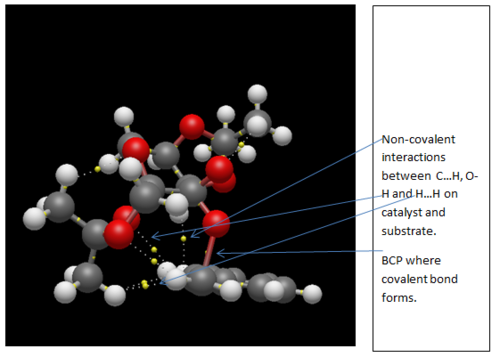

QTAIM Analysis of S-Styrene and Shi Catalyst Transition State

This section provides a greater insight into the interaction of the Shi Catalyst and Styrene as it includes both non-covalent and covalent interactions of the substrate with the catalyst. The screen shots show the covalent (bonds) and non-covalent interactions in the entire transition state and so to understand the approach of styrene to the Shi catalyst, the interactions within the active site will be focused upon. It should be noted that further non-covalent interactions are present between atoms and the lone pairs however due to the time constraints, the calculation incorporating lone pairs was not run.

Studying the QTAIM analysis, there appears to be one main interaction between the oxygen atom from the catalyst to the carbon to which the epoxide is to be formed. The bond critical point (BCP) is approximately halfway between the oxygen and carbon atoms and this trajectory leads to a formal covalent bond. There are also other non-covalent interactions near the active site. Weaker non-covalent interactions between oxygen on the acetal ring with protons on the styrene and, between protons on differing molecules can be seen but these trajectories do not lead to formal bonds: they influence the stereo-chemistry of the product as they influence the approach of the molecule to the catalyst. The screenshots are shown and annotated below.

.

.

.

.

.

QTAIN is a useful method to identify covalent and non-covalent interactions between the catalyst and substrate and identify which interactions leads to formal covalent bonds.

Suggesting A New Candidate

The following molecule was chosen to computationally determine its optical rotation:

.

The molecule was drawn and optimised in Avogadro and then submitted for NMR. Subsequently, the optical rotation calculation was run on the output file of the NMR. DOI:10042/26433 A optical rotation calculation was also run on the optimised geometry and yielded the same optical rotation as the calculation run on the output NMR file. Structure of optimised epoxide The energy of the input molecule was 41.55591 kcal/mol. The literature reports an optical rotation at 589nm of 361 deg in Benzene solvent.[9] The computed optical rotation in benzene solvent was found to be 315.37 deg. DOI:10042/26434 The computed value is positive however is lower by 45.63 deg from the literature. Since the optical rotation is a large number, the optical rotation calculation is a reliable method for determination. The relative % error was -12.64%. Deviation could arise due to interactions between molecules which can cause changes in the conformation of the molecule, not being accounted for in the computed structure.

References and Citations

1. A. McEwan, P. Schlever, "Hyperstable Olefins: Further Calculational Explorations and Predictions", J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1986, 108, 3951-3960, [1].

2. W. Maier, P. Schlever, "Evaluation and Prediction of Bridgehead Olefins", J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1981, 103, 1891-1900, [2].

3. J. Clayden, P. Wothers, N. Greeves, "S. Warren", Elimination Reactions, 2001, missing volume, 484.

4. L. Paquette, N.A. Pegg, D. Toops, "Spectroscopic Data", J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1990, 112, 277-283, DOI: 10.1021/ja00157a043.

5. H. Rzepa, "Conformational Analysis Lecture Notes: Anomeric effect", Imperial College London, 2013, missing volume, missing pages.

6. M. Ines, A. Mendonca, "Electroepoxidation of natural and synthetic alkenes mediated by sodium bromide", Universidade Agostinho Neto, Luanda, Angola, missing year, missing volume, 13, [3].

7. H. Lin, Y. Liu, Z.Wu, "Asymmetric epoxidation of styrene derivatives by styrene monooxygenase from Pseudomonas sp. LQ26: effects of a- and b-substituents", Tetrahedron: Asymmetry, 2011, 22, 134-137, [4].

8. E. Jacobsen, W.Zhang, A. Muci, "Highly Enantioselective Epoxidation Catalysts Derived from 1,2-Diaminocyclohexane", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1991, 131, 7063-7064, [5].

9. A. Solladie-Cavallo, A. Diep-Vohuule, V. Sunjic, missing title, Tetrahedron: Assymetry, 1996, 7, 1783-1788.

10. missing author1, missing title, Absolute configurational assignment in chiral compounds through vibrational circular dichroism (VCD) spectroscopy, missing year, missing volume, missing pages, [6].