Rep:Mod:PHYYLC1016

Physical Module: Charaterisation of transition structures on potential energy surface

The Cope Rearragnement

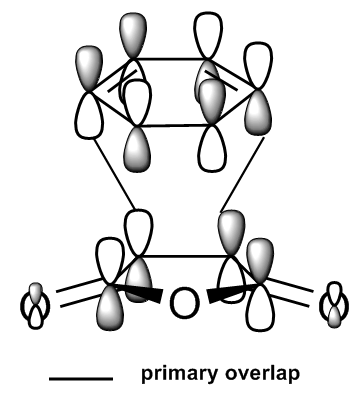

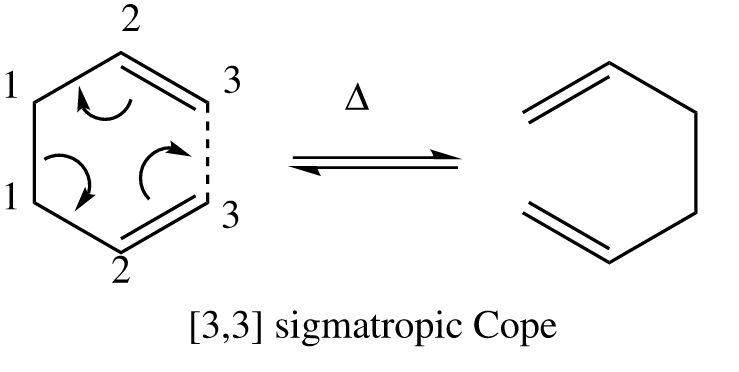

The cope rearrangement of 1,5 hexadiene is known to be an [3,3] sigmatropic shift with mechanism shown in Figure 1. The reaction generally occurs through a chair or boat transition state (TS) in a concerted manner. For the investigation of which transition state is more favourable, their structures were first optimised, followed by vibrational analysis. Based on the computed activation energies of the transition states, it found out that the chair TS has lower energy. This is matched with what we expected as chair conformation tends to have lower energy compared to the boat conformation.

Optimising the reactants and products

Introduction

The structure of 1,5 hexadiene, which is both reactant and product, was first optimised at the HF/3-21G level , followed by B3LYP/6-31G* level for locating the lowest energy conformation. A series of low energy conformers (see Table 1) were obtained from the optimisation and their identities were verified from the Appendix 1 [1]. In order to compare the computed energy with the experimental value, frequency analysis was also carried out for each conformer.

Result and Discussion

| Conformers | Anti 1 | Anti 2 | Gauche 3 | Gauche 4 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

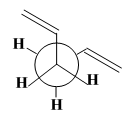

| Newman projection of the conformers |  |

|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Structure ( HF/3-21G ) |

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Total energy ( Hartrees ) | -231.69260236 | -231.69253528 | -231.69266120 | -234.69153032 | ||||||||||||

| Relative energy to Gauche 3 (kcal/mol) | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.71 | ||||||||||||

| Log File | File:REACT ANTI LINKAGE ANTI 1.LOG | File:REACT ANTI LINKAGE ANTI 2.LOG | File:REACT GAUCHE 3 LINKAGE.LOG | File:REACT GAUCHE 4 LINKAGE.LOG | ||||||||||||

| Structure ( B3LYP/6-31G* ) |

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Total energy ( Hartrees ) | -234.61179055 | -234.61170280 | -234.61132934 | -234.61048196 | ||||||||||||

| Relative energy to Gauche 3 (kcal/mol) | -0.29 | -0.23 | 0.00 | 0.53 | ||||||||||||

| The sum of electronic and zero-point energies at 0 K (Hartrees) | -234.469298 | -234.469212 | -234.468693 | -234.467784 | ||||||||||||

| The sum of electronic and thermal energies at 298.15 K (Hartrees) | -234.461966 | -234.461856 | -234.461464 | -234.460521 | ||||||||||||

| Point Group | C2 | Ci | C1 | C2 | ||||||||||||

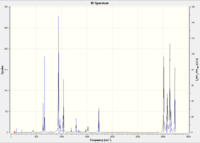

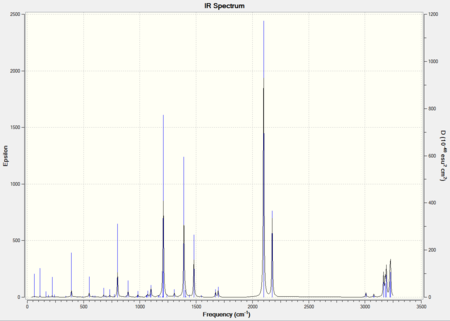

| IR spectrum |  |

|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Log File | File:DFT ANTI 1 LINKAGE.LOG File:FREQ ANTI 1 LINKAGE.LOG | File:DFT ANTI 2 LINKAGE.LOGFile:FREQ ANTI 2 LINKAGE.LOG | File:DFT GAUCHE 3 LINKAGE.LOGFile:FREQ GAUCHE 3 LINKAGE.LOG | File:DFT GAUCHE 4 LINKAGE.LOGFile:FREQ GAUCHE 4 LINKAGE.LOG |

For the judgement on whether low energy conformer was obtained from the optimisation, it can be done through two ways. Firstly, checking all forces and displacement are converged from log file of the optimisation process. Secondly, comparing electronic energies of the conformers to data shown in the Appendix 1[1] and see good matches obtained or not. The lower energy conformer was further confirmed by the frequency analysis; its vibrational frequencies are all real and positive, i.e. without any imaginary frequencies.

By looking down the central C-C bond, the conformers can be split into two main groups, Anti and Gauche forms. The geometries of the optimised structure were very similar for both basis sets and the central C-C bond in computed structure were approximately identical (0.155 nm) in 2 decimal places. This indicated that the central C-C bond length is insensitive to both basis set and the orientation of the terminal C=C bond (regardless it is anti or gauche). However, the electronic energies of the optimised conformers were sensitive to basis set. Optimised structure tend to have higher total energy at B3LYP/6-31G* theory (about 0.008 Hartrees higher, see Table 1). The difference in total energies also resulted the lowest energy conformer being either Gauche 3 ( for HF/3-21G basis set) or Anti 1 (for B3LYP/6-31G* basis set) . Despite this, electronic correlation was accounted at B3LYP/6-31G* basis set, so it is a higher level theory compared to HF/3-21G ,hence suggesting Anti 1 is the lowest energy conformation of 1,5 hexadiene instead of Gauche 3. This was matched to what we expected from the Newman projection; Anti conformation generally has lower energy due to the presence of stabilising δ C-C orbital to π * orbital interactions and the least steric hindrance in space between the two terminal C=C bond. As the stabilisation effect from interaction between δ C-C orbital and π * orbital were overlooked in the HF/3-21G optimisation [2], the Gauche 3 conformation was favoured initially. After reoptimisation at B3LYP/6-31G* level and accounted for electronic correlation, Anti 1 became the most favourable. From the relative energies of the anti conformer at B3LYP/6-31G* level, Anti 1 is more stable than Anti 2 conformer. This can be explained by the orientation of the terminal C=C bond. The two terminal C=C bond are in the same orientation in Anti 1 (shown in Newman projection, Table 1) and this enables the π to π * interaction to happen. This interaction is less pronounced for anti 2 conformer, hence it is less stable.

Optimising the Chair and Boat Transition structures

Introduction

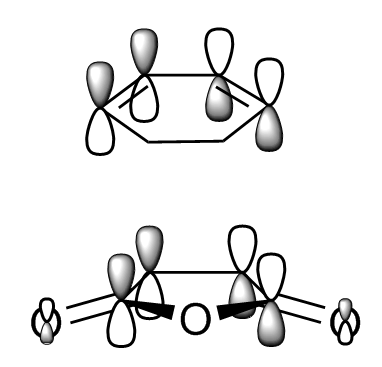

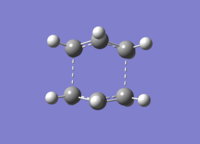

For both chair and boat TS, there have two C3H5 allyl fragments positioned in around 2.2 Å from each others. Based on the structure of C3H5 allyl fragment, TS was optimised through two different methods, normal optimisation and frozen coordinated method. While boat TS was optimised by QST2 method from the structure of anti 2 conformer of 1,5 hexadiene. Same as before, the optimisation was carried out at HF/3-21G basis set initially and followed by B3LYP/6-31G* . Basis set B3LYP/6-31G* was specially used here due to it has been shown to give energies terms in a good agreement with the experimental values

Results and Discussions

| Method | Normal Optimisation | Frozen Coordinated | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basis Set | HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G* | HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G* |

| Structure |  |

|

|

|

| Length between terminal ends (Å) | 2.02 | 1.97 | 2.02 | 1.97 |

| C-C bond length in the fragment (Å) | 1.39 | 1.41 | 1.39 | 1.41 |

| Point Group | C2h | C2h | C2h | C2h |

| The sum of electronic and zero-point energies at 0 K (Hartress) | -231.466699 | -234.414929 | -231.466701 | -234.414929 |

| The sum of electronic and thermal energies at 298.15 K (Hartress) | -231.461340 | -234.409009 | -231.461342 | -234.409009 |

| Imaginary Frequency(cm-1) | -818.0367 | -565.5418 | -818.0325 | -565.5416 |

| Log File | File:CHAIR TS GUESS OPTIMISED YLC.LOG | File:CHAIR TS GUESS OPTIMISED YLC - B3L.LOG | File:CHAIR TS GUESS FROZEN MIN YLC - 2.LOG | File:CHAIR TS GUESS FROZEN MIN YLC - 2 - B3L.LOG |

| Method | QST2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Basis Set | HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G* |

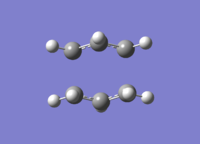

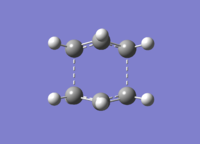

| Structure |  |

|

| Length between terminal ends (Å) | 2.14 | 2.21 |

| C-C bond length in the fragment (Å) | 1.38 | 1.39 |

| Point Group | C2v | C2v |

| The sum of electronic and zero-point energies at 0 K (Hartress) | -231.450928 | -234.402342 |

| The sum of electronic and thermal energies at 298.15 K (Hartress) | -231.445299 | -234.396007 |

| Imaginary Frequency(cm-1) | -839.9356 | -530.2989 |

| Log File | File:BOAT TS QST2 2 YLC.LOG | File:BOAT TS QST2 2 YLC - B3L.LOG |

Frequency analyses were carried out for each optimised TS structure and all of them consist of imaginary frequencies in their vibrational mode, this indicated that transition state was achieved for each case. From Table 2 and 3, it can be seem that chair TS had a more negative electronic energy than boat TS, so it is more stable. This is because the two allyl fragments are staggered in chair TS and they experiences less steric strain compare to eclipsed relationship in boat conformation. Moreover, the larger steric strain within the boat TS results a longer distance between the terminal ends of the ally fragments ( 0.12 Å longer than chair TS). The distance also is subjected to the type of basis set used for the optimisation, i.e. longer distance was observed at HF/3-21G theory. However, all the distance is shorter than sum of van der waals radii of two sp2 hybridised C atoms(3.40 Å) [3] and longer than sum of covalent radii (1.46 Å) [4]. This reflected that a bond is being formed or broken between C atom in terminal ends. Furthermore, the C-C bond length within the allyl fragment lie between standard C-C (1.54 Å) [5] and C=C (1.30 Å) [5] , this implied that the fragment has a partial double bond character, hence delocalisation of π electron.

Two methods (normal optimisation and frozen coordinated method) were employed in the optimsation of chair TS, both gave exactly the same optimised structure with same electronic energies and bond length. This could suggest that they both are good ways in determination of the chair TS structure.

After frequency analysis of the optimised TS structures, the vibrational mode of each TS can be visualised (see Figures 3, 4 and 5 below). This allowed formation and breakage of bonds in the cope rearrangement to be observed. To be notice that the vibrational modes are very similar for both chair and boat TS, carbon atoms in the one side of the terminal ends move toward each other in a concerted manner to form a bond. In the same time, the other side of the terminal ends was forced to move apart to break a bond.

Finding the Conformer form of the Chair Transition State

Introduction

Based on the transition states obtained above, it is hard to predict which conformer of 1,5-hexadiene will be lead to in following the reaction path. Despite this, Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC) method enables the minimum energy path from a transition state to its local minimum to be followed on a potential energy surface. This is done by creating a series of small geometry steps in the direction where the energy surface with the steepest slope. Optimised chair transition state form normal optimization at HF/3-21G theory was selected to undergoes IRC in a forward direction (50 steps) only due to symmetrical reaction coordinates.

Results and Discussion

| IRC | Normal minimisation of last point of IRC | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure |

|

| ||||||

| Point group | C2h | C2 | ||||||

| Dihedral angle (degree) | 67.2 | 64.2 | ||||||

| Electronic energy (a.u.) | -231.61932229 | -231.69166702 | ||||||

| IRC Path |  |

N/A | ||||||

| Log File | File:CHAIR TS GUESS OPTIMISED YLC - ISC.LOG | File:CHAIR TS GUESS OPTIMISED YLC - ISC - opt.LOG |

The results were summarised in the Table 4 above. After the ISC calculation, a conformer of 1,5-hexadiene with a close structure to Gauche 2 was obtained. However, it had a slightly higher energy compared to the one of Gauche 2 listed in Appendix 1 [1]. This implied that it has not reached minimum geometry yet. In order to reach the minimum geometry, last point of the IRC calculation was taken to run a normal optimisation process at HF/3-21G basis set. A structure with a lower energy than the last point of the IRC was given, it also had exactly same energy and symmetry as Gauche 2 (see Appendix 1 [1]). This confirmed that the last point of the initial IRC calculation was not a local minimum and further optimisation does help in achieving the minimum geometry, which is Gauche 2 in this case. The dihedral angle of the conformer was slightly reduced upon optimisation as well and this might the origin in minimising the energy. Thereby, Gauche 2 is the conformer that chair Transition state lead to in this cope rearrangement reaction.

Activation Energies for each transition state

Introduction

The activation energies for the cope rearrangement reaction via chair and boat transition state were obtained from the result of the frequency analysis of the optimised TS at HF/3-21G and B3LYP/6-31G*level of theory. The calculated results and experimental comparison were summarised in below.

Results and Discussion

| Chair TS | Boat TS | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| at 0 K | at 298.15 K | at 313.15 K | at 0 K | at 298.15 K | at 313.15 K | ||||||||

| Basis Set | HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G* | HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G* | HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G* | HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G* | B3LYP/6-31G* | HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G* | HF/3-21G | |

| Computed Ea | 45.71 | 34.06 | 44.69 | 33.16 | 44.65 | 33.12 | 55.60 | 41.96 | 54.80 | 41.32 | 54.73 | 41.31 | |

| Experimental Ea | 33.5±0.5 [6] | N/A | N/A | 44.7±2.0[7] | N/A | N/A | |||||||

| Percentage difference to Experimental value | 36.4 | 1.68 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 24.4 | -6.13 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

The activation energies at three different temperature were calculated based on the energy of Anti 2 conformer (listed in Table 1) as Anti 2 conformer was used specially in the locating the boat TS. Energy terms at 0 K and 298.15 K were obtained from the frequency analysis of the optimised structure whereas energy terms at 313.15 K was computed using ‘’’ Freqcheck’’’ function in Gaussian09. The computed activation enegies of chair TS are smaller than the boat TS one regardless the basis set used and the temperature it under. This implied that the cope rearrangement of 1,5 hexadiene happen via chair TS preferially. The activation energies at 0 K computed using B3LYP/6-31G* had much smaller percentage difference to the experimental(<± 7%). This confirmed that B3LYP/6-31G* is a better theory in calculating electronic and thermal energies than HF/3-21G and it is a good theory for this reaction. However, optimising the structure first at HF/3-21G theory, then reoptimising at B3LYP/6-31G* is a more computational efficient way to do so. From the Table 5, the computed activation energies increased with temperature was observed.

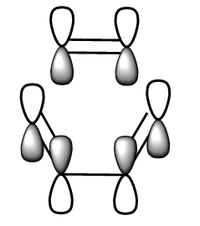

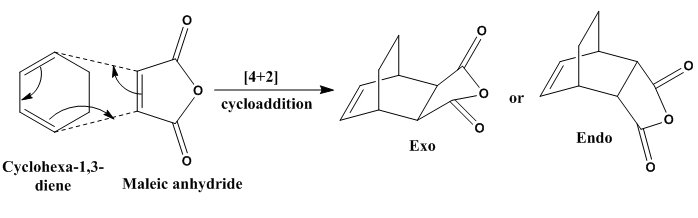

The Diels Alder Cycoaddition

The Diels Alder Cycloaddition is an example of pericyclic reaction, with [4+2] mechanism. The reaction generally happens between a diene and dieneophile and σ bond will be formed between their π-orbitals. From the molecular orbital point of view, HOMO/LUMO of one of the reactant (i.e. diene or dieneophile) interacts with LUMO/HOMO of another reactant in forming a new set of bonding and antibonding MO. If the reaction proceeds thermally, Huckel topology will be applied to the stereochemistry, i.e. with suprafacial components only. This explained why the Diels Alder Cycloaddition occurs in a concerted stereospecific fashion. Whether the reaction is allowed or forbidden is depended on two factors. Firstly, the number of π electron involve in the reaction can be important. The number of π electron need to be fitted in 4n+2 rule (where n=1 in this case) under thermal condition or fitted in 4n rule under photochemical condition. Secondly, the HOMO and LUMO pair needs to have same symmetry for significant overlap between them, hence the reaction can be proceeded. Moreover, it is common that the dieneophile are disubstituted. It is possible for π orbitals on the substituents to interact with the new formed double bond in the product. This π - interaction stabilises the TS of one of the possible regioisomer (Exo or Endo) and lead to its formation preferentially at the end. This is known as the effect of second orbital overlaps.

Cycloaddition between Ethene and Cis-Butadiene

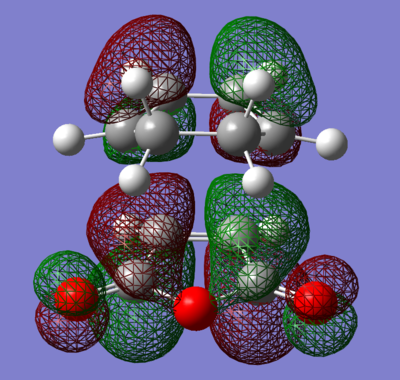

Cyclohexene was formed in the cycloaddition of cis-butadiene and ethane. As both substituents on the dieneophile (ethane) are simply H atoms, no second orbital overlap effect is expected to be observed. Therefore, there has no issue of regioselectivity in the product. It was known that the HOMO of ethane and the LUMO of cis-butadiene are both symmetric with respected to the reflection plane whereas the LUMO of ethane and HOMO of cis-butadiene are both antisymmmtric.

Optimisation of Cis-Butadiene

Cis-butadiene was optimised at Semi-empirical/AM1 Semi-empirical molecular method, followed by the B3LYP/6-31G* basis set. The structure and symmetry of the HOMO and LUMO of Cis-butadiene were shown in the Table 6 below.

| Basis Set | Semi-empirical/AM1 | B3LYP/6-31G* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optimised Structure |

|

| ||||||

| Electronic Energy (a.u.) | 0.04878534 | -155.98648970 | ||||||

| Point Group | C2 | C2 | ||||||

| Log File | File:CIS BUTADIENE OPTIMISED AM1 YLC.LOG File:CIS BUTADIENE FREQ AM1 YLC.LOG | File:CIS BUTADIENE OPTIMISED DFT YLC.LOG File:CIS BUTADIENE FREQ DFT YLC.LOG | ||||||

| Structure of HOMO |  |

| ||||||

| Symmetry of HOMO | Antisymmetric | Antisymmetric | ||||||

| Structure of LUMO |  |

| ||||||

| Symmetry of LUMO | Symmetric | Symmetric |

The optimised structure obtained from both methods has the same point group but the dihedral angle along central C-C bond was two times larger for the structure obtained from the B3LYP/6-31G* theory. The structure from B3LYP/6-31G* basis set has much lower energy, so it might suggest this is the minimum geometry of cis-butadiene. The symmetries of plotted HOMO and LUMO are antisymmetric and symmetric respectively, this is exactly the same mentions previously. As the optimised structure from B3LYP/6-31G* theory is more bent in structure, so the obtained MOs is less symmetrical than the one from Semi-empirical/AM1 method.

Optimisation of transition state and examination of the nature of the reaction path

Transition state optimisation was set up by computing the force constants at the beginning of the calculation. Several transition state structures were guessed and modified before achieving successful calculation. It found out that a good guess structure of the transition state can be obtained by modifying the expected product geometry in to the two corresponding reactants structure. Moreover, linear combination of atomic orbitals (LCAO) method was used in given a better illustration on how the frontier orbitals overlap in the TS and results the corresponding HOMO and LUMO structures. The results were summarised in below.

| Basis Set | Semi-empirical/AM1 | B3LYP/6-31G* |

|---|---|---|

| Optimised Structure |

|

|

| Electronic Energy (a.u.) | 0.11165477 | -234.54389654 |

| Point Group | Cs | Cs |

| Distance between terminal ends (Å)(bond length of partially formed σ C-C bond) | 2.12 | 2.27 |

| Imaginary Frequency (cm-1) | -956.26 | -525.07 |

| Log File | File:CYCLO 1 TS OPTIMISED AM1 GUESS YLC.LOG | File:CYCLO 1 TS OPTIMISED DFT GUESS YLC.LOG |

| Basis Set | Semi-empirical/AM1 | |

|---|---|---|

| MO | HOMO | |

| Structure |  |

|

| Symmetry | Antisymmetric | Antisymmetric |

| MO | LUMO | |

| Structure |  |

|

| Symmetry | Symmetric | Symmetric |

The distance between terminal ends was set to be 2.0 Å in the guess structure and turned out that it is (2.12 Å / 2.27 Å). From Table 7, the distance between terminal ends of the reactants is shorter than sum of van der waals radii of two sp2 hybridised C atoms(3.40 Å) [3] and longer than sum of covalent radii (1.46 Å) [4]. This indicated a C-C sigma bond was partially formed. The bond lengths of C=C bonds within the reactants lies between typical sp3 C-C (1.54 Å [5]) and sp2 C-C bond (1.30 Å [5]). This indicated that these bonds are being broken in the transition state. From both theories, optimised geometries were associated with imaginary frequencies, this proved that the structure of transition state was achieved. In addition, the HOMO of TS is constructed from the antisymmetric HOMO of cis-butadiene and anti symmetric π * orbital of ethane, so it is antisymmetric overall. Same for symmetric LUMO, in which is constructed from symmetric LUMO of cis-butadiene and π orbital of ethane. It also can be seem that the electron density was concentrated in the region where new σ C-C bond formed, suggesting there has a good overlap between frontier orbitals, hence this cycloaddition is allowed and via [4s+2s] mechanisms.

The vibrational mode of the TS at Semi-empirical/AM1 were shown below, this enabled the new σ bond formations to be investigated.

For Semi-empirical/AM1 , the vibrational mode corresponds to the reaction path at the transition state was shown in the Figure 8. The terminal ends of ethene and cis-butadiene were approached to each other in a concerted manner during the vibration, this implied that the two new sigma C-C bonds was formed synchronously. Unlike the stretching modes in the TS vibrational frequency, both molecules were undergoes bending motions at the lowest real vibrational frequency ( 147.09 cm-1, Figure 9). More structural changes involve in the vibration of the TS, so a higher energy will be needed in causing vibration, hence a larger in magnitude of vibrational frequency was observed for TS.

Cycloaddition between Maleic Anhydride and Cyclohexadiene

For this cycloaddition, the dieneophile (maleic anhydride) is an electron-withdrawing species, i.e. it is electron deficient, this in turn forcing the regular Diels–Alder cycloaddition. It is di-substituted in nature, so the π orbitsls on the C=O bonds are possible involving in the second orbital overlap effect. Which regioisomer (Exo or Endo) will be preferred in this reaction is dependent on the balance between steric and electronic effects and they were studied below.

Optimistaion of the transition state and study of regioselectivity

The transition state structure for both Exo and Endo were optimised using same methods as for TS in previous cycloaddition reaction. The distance between the C atoms, where the new σ C-C bonds will be formed, were guessed to be 2.2 Å prior the optimisation. The computed results were listed below.

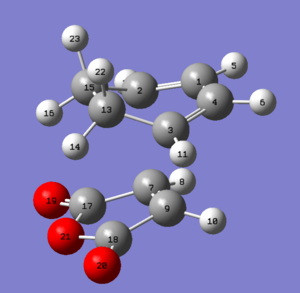

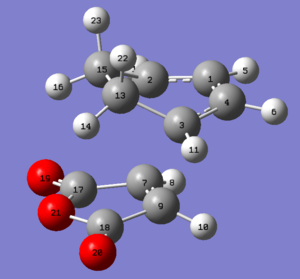

| ENDO | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basis Set | Semi-empirical/AM1 | B3LYP/6-31G* | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Structure |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Point Group | Cs | Cs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronic energy (a.u.) | -0.05150480 | -612.68339679 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Imaginary Frequency(cm-1) | -806.4446 | -446.8043 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Log File | File:CYCLO2 TS OPTIMSED ENDO BEFORE ylc.LOG | File:CYCLO2 TS OPTIMSED ENDO DFT.LOG | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| EXO | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Basis Set | Semi-empirical/AM1 | B3LYP/6-31G* | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Structure |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Point Group | Cs | Cs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronic energy (a.u.) | -0.05041984 | -612.67931096 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Relative Electronic energy to ENDO (a.u.) | 0.00108496 higher | 0.0040858 higher | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Imaginary Frequency(cm-1) | -812.0740 | -448.4461 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Log File | File:CYCLO2 TS OPTIMSED EXO AM1 YLC.LOG | File:CYCLO2 TS OPTIMSED EXO DFT YLC.LOG | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Both transition states were successfully optimised and this can be reflected from the fact that partially formed sigma C-C bond (Endo: C3-C11 and C2-C9; Exo: C3-C9 and C2-C7) have equal bond lengths. Imaginary frequencies were also observed for both structure, confirmed once again that optimized TS structure were computed. From the work of A.Arrieta et al [8], the distances of new formed C-C bonds were calculated at B3LYP/6-31G* basis set and reported (Endo: 2.22 Å and Exo: 2.24 Å ). They are in a good agreement to the computed values in Table 9 above (Endo: C15-C17 ; Exo: C1-C4 ). The HOMO and LUMO of both TS were plotted in Table 10, along with its frontier orbitals orientations. The main structural difference between Endo and Exo TS was the orientation of cyclohexadiene ring to the maleic anhydride. For Endo TS, -CH2-CH2- fragment of cyclohexadiene is in opposite side with –(C=O)-O-(C=O)- of maleic anhydride. While for Exo TS, -CH2-CH2- fragment of cyclohexadiene is in same side with –(C=O)-O-(C=O)- of maleic anhydride. This indicated that Exo TS associated with a greater steric hinderance, hence more strained. The distances between C15-C20 and C17-C19 for Endo TS and C15-C20 and C17-C19 for Exo TS are the balance of steric hindrance (increases) and orbital overlaps (decrease). In general, the bond length is longer for Exo TS than Endo one. As previously stated, the partial formed bonds had very similar lengths for both TS; this implied that they were not much affected by the larger steric hindrance presented in Exo TS. To concluded, from the steric point of view, Exo adduct is disfavoured in this cycloaddition.

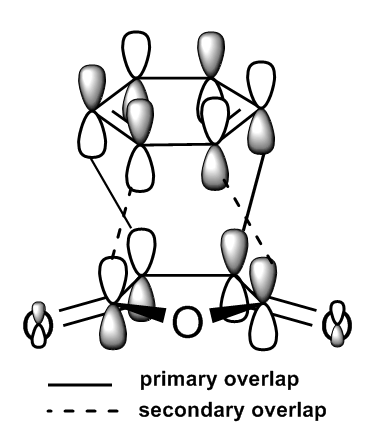

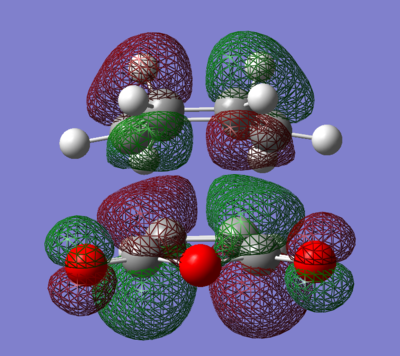

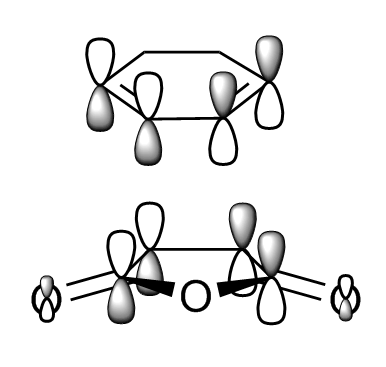

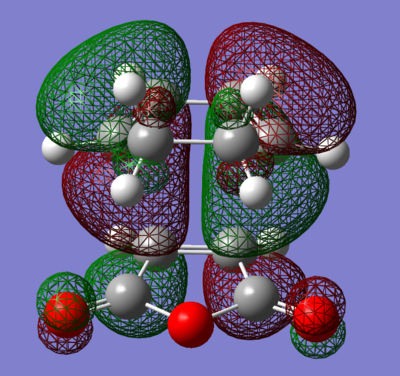

Same as before, linear combination of atomic orbitals (LCAO) method was employed in given a better illustration on how the frontier orbitals overlap in the TS and results the corresponding HOMO and LUMO structures. The results were summarised in below.

From the energies of the TS, Endo TS has slightly lower in energy overall, so it is more stable. Therefore Endo adduct is the kinetic product while the Exo adduct is the thermodynamic product. The Endo TS has lower energy due to the presence of secondary orbitals overlaps (the dashed line shown in the figures in the Table 10). The overlaps are non-bonding interactions between frontier orbitals of both reactants. In the case of Endo TS, the π orbitals of the C=O bonds of maleic anhydride overlap with the HOMO of cyclohexadiene. There has no similar interaction presents in the Exo TS due to the new formed double bond away from the C=O bonds. No stabilization can be gained, so Exo TS had slightly higher energy. Based on the steric effect and the Secondary Orbital Overlaps, Endo TS is both energetically favoured.

The vibrational mode of the TS at Semi-empirical/AM1 were shown in the Figure 10, this enabled the new σ bond formations in this reaction to be investigated.

It can be seem that the bond was synchronously formed. Compared to the vibrational mode of the cycloaddition between ethene and cis-butadiene, they were quite similar in nature as well.

Effect Neglected in Semi-Empirical/AM1 Calculation of Diels Alder TS

AM1 is a semi-empirical method for the calculation of molecular electronic structure in quantum mechanics aspect. It mainly based on Neglect of Differential Diatomic Overlap integral approximation (NDDO), in which the repulsion of atoms at close separation distances was reduced. [9]. From the first part of this investigation, B3LYP/6-31G* theory was found to have good performance for molecular thermodynamic. This is because the effects of polarization are taken into account in this theory[10]. Therefore, it was used in the further calculations of TS for giving more reliable results (see above). The downside for B3LYP/6-31G* theory is the checkpoint files of the TS for both cycloaddition cannot open successfully due to bad data, so no MOs can be plotted. Thereby, the HOMOs and LUMOs shown in above were obtained from AM1 calculation

Short Summaries for Diels-Alder Cycloadditions

Semi-empirical/AM1 theory was used in initial optimisation and followed by B3LYP/6-31G* thoery is a quite good way to give reasonable results. As the outcome of the computation were in good matches with those obtained from experimental. Computational methods can be a good tool in studying and predicting the molecular thermodynamic of Diels-alder cycloaddition reaction. Second orbital overlaps play an important role in determining the outcome of the reaction, but the relative orientation of the frontier orbitals and steric effects also need to be accounted as well.

Future work

- Generating a guess structure for boat TS of the cope rearrangement and see whether the calculation converge using the reactants and products molecules. Also comparing the results to the one obtained from QST2 methods.

- After first IRC calculation, one out of three options was selected in locating the minimum geometry of the product. Time was not sufficient enough to try on the two remained options, and it would be good to carried out in the future. This can be used to confirmed the actual minimum conformer of the cope rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene is Gauche 2.Options are (1) restart IRC and specify a larger number of points until it reaches a minimum and (2)Redo the IRC and compute the force constant in every step

- The TS of Diels-Alder Reaction were calculated by computing the force constants at the beginning of the calculation. However, the optimsation with the QST2 methods should be carried out and comparing it to computed results in this investigation.

- Using a more advanced theory instead on those used above in the calculation of Diels alder reaction. The example can be B3LYP-gCP-D3/6-31G*, which was demonstrated practical advantages in calculation and showed its higher robustness over standard B3LYP/6-31G* basis set[10].

- Investigating other Diels Alder cycloadditions, such as with 4-Chloro-2(H)-pyran-2-one[11]. In which, the dieneophile is monosubstitied and electron deficient. Regio and stereo selectivity of the reaction should be studied and see whether they are in line with the experimental results.

Reference

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Imperial College London, https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=Mod:phys3#Appendix_1

- ↑ BRANDON G. ROCQUE, JASON M. GONZALES & HENRY F. SCHAEFER III, " An analysis of the conformers of 1,5-hexadiene ", Molecular Physics, 2002, 100 , '4 ',441-446.DOI:10.1080/00268970110081412 10.1080/00268970110081412

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Bondi, A., " "Van der Waals Volumes and Radii" ", J. Phys. Chem., 1964, 68 , '3 ',441-451.DOI:10.1021/j100785a001 10.1021/j100785a001

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Beatriz Cordero, Verónica Gómez, Ana E. Platero-Prats, Marc Revés, Jorge Echeverría, Eduard Cremades, Flavia Barragán and Santiago Alvarez, " " Covalent radii revisited " ", Dalton Trans., 2008, 21 ,2832-2838.DOI:10.1039/b801115j 10.1039/b801115j

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Linus Pauling, " General Chemistry ", Courier Dover Publications, 1988, 1-959

- ↑ W. von E. Doering, V.G. Toscano, G.H. Beasley, " Kinetics of the cope rearrangement of 1,1-dideuteriohexa-1,5-diene ", Tetrahedron, 1971, 27 , '22 ',5299-5306.DOI:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)91694-1 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)91694-1

- ↑ M. J. Goldstein and M. S. Benzon, " Boat and chair transition states of 1,5-hexadiene ", J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1972, 94 , '22 ',7147-7149.DOI:10.1021/ja00775a046 10.1021/ja00775a046

- ↑ Ana Arrieta and Fernando P. Cossío, Begoña Lecea, " "Direct Evaluation of Secondary Orbital Interactions in the Diels−Alder Reaction between Cyclopentadiene and Maleic Anhydride" ", J. Org. Chem., 2001, 66, '18 ', 6178–6180.DOI:10.1021/jo0158478 10.1021/jo0158478

- ↑ J. Pople and D. Beveridge, " Approximate Molecular Orbital Theory ", McGraw-Hill., 1970

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Theoretische Organische Chemie, Organisch-Chemisches Institut der Universität Münster; School of Chemistry, The University of Sydney;Mulliken Center for Theoretical Chemistry, Institut für Physikalische und Theoretische Chemie der Universität Bonn" " Why the Standard B3LYP/6-31G* Model Chemistry Should Not Be Used in DFT Calculations of Molecular Thermochemistry: Understanding and Correcting the Problem" ", J. Org. Chem., 2012, 77, '23 ', 10824–10834.DOI:10.1021/jo302156p 10.1021/jo302156p

- ↑ Kamyar Afarinkia ,* Michael J. Bearpark , andAlexis Ndibwami" " Computational and Experimental Investigation of the Diels−Alder Cycloadditions of 4-Chloro-2(H)-pyran-2-one " ", J. Org. Chem., 2003, 68, '19 ', 7158-7166.DOI:10.1021/jo0348827 10.1021/jo0348827