Rep:Mod:PAUL

The Cope Rearrangement Tutorial

In this tutorial the Cope rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene was used as an example to study a chemical reactivity problem. The computational methods were used to locate the low-energy minima and transition structures (TS) on the potential energy surface and to determine the preferred reaction mechanism. This reaction is a [3,3] sigmatropic shift where the allyl group migrates. The reaction obeys the (4n+2) electron rule and proceeds via the Hückel transition state. It is generally accepted that the reaction occurs with a concerted mechanism via two possible transition stuctures: chair and boat, the latter being slightly higher in energy.

Optimising the reactants and products

In this section the structure was optimised, its point group was determined by symmetry operations, vibrational frequencies and correct potential energies were calculate and visualised in order to compare them with experimental values.

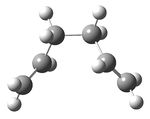

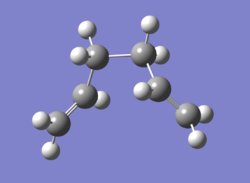

Using GaussView 5.0, a molecule of 1,5-hexadiene was drawn with an anti linkage for the central four carbon atoms (antiperiplanar) and cleaned. Then the structure was then submitted for optimisation using the Hartree Fock method with the default basis set 3-21G. The energy of the optimised structure was -231.69260235 a.u. and the symmetry point group was found to be C2.

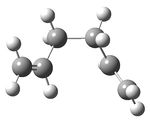

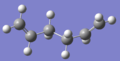

The same procedure as described above was performed on 1,5-hexadiene with the gauche linkage for four central C atoms. The molecule was determined to have the energy of -231.69166702 a.u. with the C2 symmetry point group.

Considering the conformations from the steric point of view, it is expected that the anti conformer would be lower in energy than the gauche one. This is simply due to the bulky groups being further away in the anti conformer rather than gauche, in this way reducing the relative energy of the molecule. The computational method used for the energy calculation indeed confirms this and it can be seen that the energy of gauche conformer is higher than anti by 9.3533×10-4 a.u.

| Conformation | Structure | Energy | Point Group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti |  |

-231.69260235 a.u. | C2 |

| Gauche |  |

-231.69166702 a.u | C2 |

In general, calculated activation energies and enthalpies use the lowest energy conformation of a reactant molecule as a reference. Based on the results obtained above, the predicted conformer with the lowest energy is the same anti conformer from above, since it has the bulky groups positioned in the opposite directions and as far apart from each other as possible.

The structures obtained were compared to the ones in Appendix 1 and good agreement was found. The corresponding conformers are anti1 and gauche2 in the Table 2.

| Conformer | Structure | Point Group | Energy/Hartrees HF/3-21G |

Relative Energy/kcal/mol |

| gauche | C2 | -231.68772 | 3.10 | |

| gauche2 | C2 | -231.69167 | 0.62 | |

| gauche3 | C1 | -231.69266 | 0.00 | |

| gauche4 | C2 | -231.69153 | 0.71 | |

| gauche5 | C1 | -231.68962 | 1.91 | |

| gauche6 | C1 | -231.68916 | 2.20 | |

| anti1 | C2 | -231.69260 | 0.04 | |

| anti2 | Ci | -231.69254 | 0.08 | |

| anti3 | C2h | -231.68907 | 2.25 | |

| anti4 | C1 | -231.69097 | 1.06 |

The anti2 conformation of 1,5-hexadiene was drawn and optimised at the HF/3-21G level of theory. As expected, the conformer was found to have Ci symmetry point group. The energy of the conformer was determined to be -231.69253516 a.u. which perfectly agrees to the value in Appendix 1.

The molecule was then reoptimised using the B3LYP/6-31G* higher level of theory. In the density functional theory (DFT) method the total energy is expressed in terms of the total electron density and not the wavefunction. It uses an approximate Hamiltonian and an approximate expression for the total electron density [1]. Optimising the structure using different methods does not have any effect on their symmetries, however it results in the change of their geometry, i.e. bond lengths and bond angles are seen to change.

(By how much do they change? Would you consider that you obtained different structure? João (talk) 00:41, 28 December 2014 (UTC))

Moreover, the relative energy was determined to be -234.55969661 using the B3LYP/6-31* level of theory, which significantly differs from the one obtained with HF/3-21G. However, it is important to note that the energies cannot be compared when different methods are used.

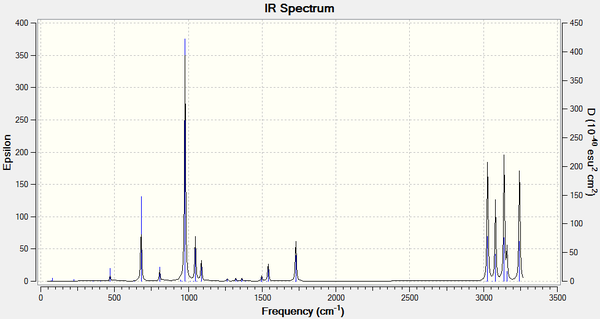

The final energies given in the output represent the energy of the molecule on the bare potential energy surface. In order to compare the energies with measured quantities, they need to include additional terms, which requires a frequency calculation to be performed. The frequency calculations are also needed for characterisation of the critical point (the structure reported as being the optimum one) by confirming the fact that it is a minimum point on the potential energy surface. In that case all vibrational frequencies calculated should be real and positive. The IR spectrum with frequencies was visualised and shown below.

The resultant structure was then submitted for a frequency calculation using the same as before B3LYP/6-31G* method. The output file was used to ensure that all frequencies were indeed real and positive. Thermochemistry section in the output file was accessed to determine the information of energies described in the Table 3.

| Energy contribution: sum of electronic and... | Description | Value, a.u. |

|---|---|---|

| Zero-point energies | Potential energy at 0 K including the zero point energy | -234.416252 |

| Thermal energies | Energy at 298.15 K and 1 atm of pressure, contributions from the translational, rotational, and vibrational energy modes | -234.408952 |

| Thermal enthalpies | Contains an additional correction for RT (H = E + RT) which is particularly important when looking at dissociation reactions | -234.408008 |

| Thermal free energies | Includes the entropic contribution to the free energy (G = H - TS) | -234.447897 |

Optimizing the Chair and Boat Transition Structures

In this section the transition structure optimisation was set using the following methods: by computing the force constants at the beginning of the calculation; using the redundant coordinate editor; and by using QST2. The reaction coordinate was also visualised and the intrinisic reaction coordinate (IRC) was run in order to calculate the activation energies for the Cope rearrangement which proceeds via either the chair or boat transition structures (TS).

The transition state of a chemical reaction is the saddle point on the potential energy surface. This means that the TS lies on the potential energy surface such that dV/dr=0 and that this point corresponds to the maximum along the reaction coordinate and to the minimum in all other directions.

Chair structure

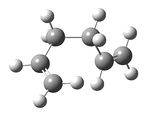

An allyl fragment was drawn in GaussView and optimised using the HF/3-21G option. The optimised structure was then copied and pasted twice to produce the chair structure of the two fragments positioned approximately 2.2A from each other. The resultant structure was then optimised using the following methods: by computing the Hessian matrix; and by freezing the reaction coordinate.

Hessian Matrix

Hessian matrix was computed using the following procedure: the guessed structure was set up for optimisation for a transition state (Berny) with calculating frequencies. The method used was HF/3-21G level of theory. Force constants were set to be calculated once and opt=noeigen was typed in the additional keyword box which stops the calculation crashing if more than one imaginary frequency is detected during the optimisation which can possibly happen if the guessed transition structure does not closely resemble the real one.

The imaginary frequency was found to be -818.11 cm-1. This value corresponds to the Cope rearrangement which is visualised in Fig. 4.

Freezing coordinates

The frozen coordinate method was then run on the guessed structure from before. The bonds between the two sets of terminal C were frozen at 2.2Å using the redundant coordinate editor. The structure was then submitted for optimisation using the HF/3-21G method.

The resultant structure was then resubmitted for optimisation to a transition state. The frozen bonds at 2.2Å were changed to derivatives in the redundant coordinate editor in GaussView. The method used was again the HF/3-21G level of theory. The procedure yielded the same imaginary frequency -818.11 cm-1 as with Hessian matrix.

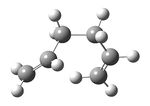

Boat structure

The boat transition structure was optimized using the QST2 method. Using this method the reactants and products of a reaction need to be specified and the calculation interpolates the two structures to try to find the transition state between them. Reactants and products were manually numbered accordingly.

The structures were then submitted to optimise using the QST2 method with HF/3-21G level of theory. The optimisation job failed and the resultant structure did not look like a boat. Alternatively, it resembled the dissociated chair transition state with bond lengths of 3.24Å between the corresponding carbons. In fact, upon linear interpolation between the reactant and the product, the top allyl fragment was translated without without taking into account the possible rotation around the central bonds. The QST2 method was proved to be ineffective for locating the transition structure between the reactant and the product.

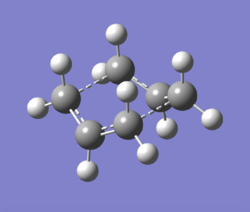

Following the QST2 failure to compute transition structure, the geometry of the reactant and product were manually configured as follows: the central dihedral angle (C2-C3-C4-C5) was set to 0° and the inside angles C2-C3-C4 and C3-C4-C5 were set to 100°. The optimisation using the same parameters was submitted again and the job was successfully processed.

| Geometry | Energy, a.u. | Imaginary frequency, cm-1 |

|---|---|---|

| Chair | -231.619472 | -818.11 |

| Boat | -231.603187 | -840.28 |

(Didn't you attempt to do the IRC from the transition states found? Didn't you re-optimize the transition state at a higher level of theory? What are the activation energies for the reaction through each of the transition states and how do they compare with experiments/literature? João (talk) 00:41, 28 December 2014 (UTC))

The Diels Alder Cycloaddition

The Diels Alder reaction belongs to a class of reactions known as pericyclic reactions. The π orbitals of the dieneophile are used to form new σ bonds with the π orbitals of the diene. Whether the reactions occur in a concerted stereospecific fashion (allowed) or not (forbidden) depends on the number of π electrons involved. In general the HOMO/LUMO of one fragment interacts with the HOMO/LUMO of the other reactant to form two new bonding and anti-bonding MOs. The nodal properties allow one to make predictions according to the following rules:

- If the HOMO of one reactant can interact with the LUMO of the other reactant then the reaction is allowed.

- The HOMO-LUMO can only interact when there is a significant overlap density. If the orbitals have different symmetry properties then no overlap density is possible and the reaction is forbidden.

If the dieneophile is substituted, with substituents that have π orbitals that can interact with the new double bond that is being formed in the product, then this interaction can stabilise the regiochemistry (i.e. head to tail versus tail to head) of the reaction. In this exercise the nature of the transition structure for the Diels-Alder reaction was studied.

Cis-butadiene reaction with ethylene

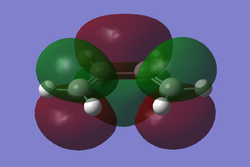

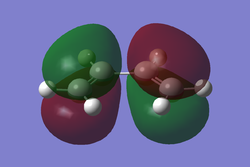

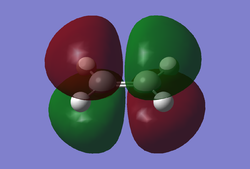

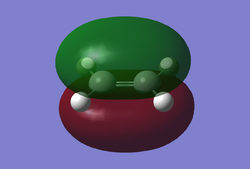

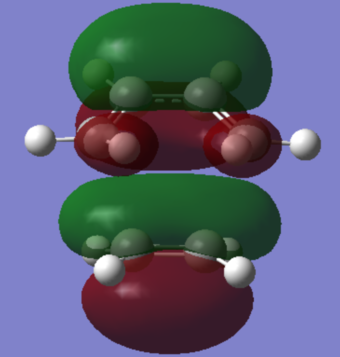

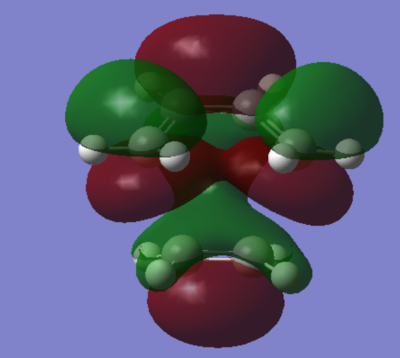

A molecule of cis-butadiene was drawn in GaussView and optimised using the AM1 semi-empirical method. After optimisation the HOMO/LUMO orbitals were visualised and can be seen below.

Fig 6a LUMO |

Fig 6b HOMO |

Fig 7a LUMO |

Fig 7b HOMO |

These molecular orbitals are asymmetric with respect to the plane of the molecule. The HOMO of butadiene and the LUMO of ethylene are both antisymmetric with respect to the σv plane. Alternatively, the LUMO of butadiene and the HOMO of ethene are symmetric with respect to the same plane. Regarding the reactivity of the system, it is known that in order to overlap and form a bond orbitals have to be of the same symmetry.

Transition State

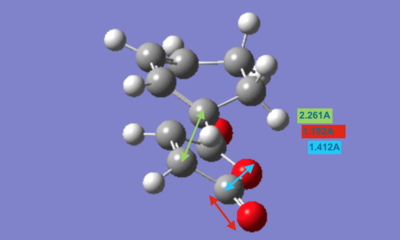

The transition state of cis-butadiene reaction with ethylene was calculated by computing the Hessian matrix from a guessed structure. The structure was made from a bicyclic system by removing two additional CH2-CH2 fragments. The two remaining fragments were positioned manually to set the distance between them at about 2.2 Å.

The structure was then submitted for optimisation to the Berny transition state using the HF/3-21G level of theory always calculating the force constant.

The bond lengths between carbons that form the new σ bond were determined to be 2.237Å, which is larger than the actual carbon-carbon bond of 1.54Å. The single bond in cis-butadiene decreases in length to 1.402Å compared to single C-C bond of 1.54Å. The double C=C bond in ethylene fragment was found to be were found to be 1.361Å, longer than a typical C=C bond of 1.32Å. All of these observed changes in bond lengths are the expected result of the reaction proceeding form the reactants to the transition state. This is due to C=C lengthening as C undergoes transition from sp2 to sp3 hybridisation and similarly C-C contraction when going from sp3 to sp2 hybridisation.

Due to the fact that the Van der Waals radius of C is 1.70Å and the two carbons that form the new bond are 2.237Å apart, van der Waals radius doubled is significantly higher than the distance between the mentioned carbons. This means that the forming C-C bond we are considering corresponds to a bonding interaction. The imaginary frequency was found to be at -927.51 cm-1 and therefore it corresponds to the concerted Diels-Alder bond formation.

(What are the symmetry characteristics of the transition state orbitals? Do they results from the orbital combination you conjectured in the introduction? Why is the reaction allowed according to the Woodward-Hoffmann rules? João (talk) 00:41, 28 December 2014 (UTC))

Cyclohexa-1,3-diene reaction with maleic anhydride

Cyclohexa-1,3-diene readily reacts with maleic anhydride via Diels-Alder cycloaddition. The endo product is the kinetic product and is formed in higher proportion to the minor endo product. Due to this reason, it can be assumed that the endo transition state is lower in energy than the endo one.

The cyclohexa-1,3-diene fragment was drawn in GaussView as a bicyclic structure and then optimised using the HF/3-21G level of theory. In order to obtain the desired diene fragment, two CH2 fragments needed to be removed. Maleic anhydride was similarly drawn and optimised using the same method as for cyclohexa-1,3-diene. The two fragments were brought together and positioned at approximately 2.20Å from each other in an appropriate orientation depending on whether the structure is exo or endo.

The resulting fragments were then optimised to the Berny transition state using the HF/3-21G level of theory with always calculating the force constants. After optimising both endo and exo transition states, the energies were found to be -605.61036823 a.u. and -605.60359125 a.u., respectively. As expected, the exo transition state is higher in energy than the endo transition state.

Both endo and exo transition structures are symmetrical; however, two transition structures have slight differences in the bond lengths between the two fragments. The fragments seem to be closer to each other in the endo transition state. This supports the idea of an orbital overlap between the π orbitals of the (C=O)-O-(C=O) and the CH=CH fragment in the endo structure being the reason for favoured fomation of endo product.

(Do you actually see this orbital overlap from the orbitals of your calculation? João (talk) 00:41, 28 December 2014 (UTC))

However, it is important to note that the mentioned bond length difference is rather small and this does not enable us to draw a finite conclusion.

The energy of the exo transition state was found to be -605.60359125 a.u. and the energy of the endo transition state was found to be -605.61036823 a.u. Since the energy of the endo transition state is lower than the energy of the exo transition state, as expected, it can be confirmed that the reaction via the endo pathway is the kinetically favoured route. The stability of the endo transition structure can be explained by the secondary orbital overlap which does not result in bond formation, but does have a contribution to the stabilisation of the endo structure.

This can also be explained in terms of steric repulsion in the exo transition state between the bridging carbons in the cyclohexa-1,3-diene and the =O groups on the maleic anhydride, which has a strong effect in exo structure but is insignificant in endo (Which bond lengths are relevant to illustrate the mentioned steric hindrance? João (talk) 00:41, 28 December 2014 (UTC)). The bond lengths in the transition states agreed well with the expected values, with maleic anhydride double bond and double bonds on they cyclohexa-1,3-diene lengthening and with a stronger single bond character.

Conclusion

This experiment focused on the computational techniques applied to a range of reactive systems, such as the cope rearrangement and Diels-Alder reaction. The transition structures of the reactive systems were determined and analysed, in terms of relative energies and interactions. The regioselectivity of the cycloaddition was investigated and computational experimental results were compared to experimental observations giving a generally good agreement.

References

[1] Computational Chemistry and Molecular Modelling, K.I Ramachandran, G. Deepa, K. Namboori, Springer 2008.

[2] The Gaussian '09 User Reference.

[3] Appendix 1, Year 3 Computational Lab, Imperial College London.

[4] Orbital symmerties and Endo-Exo Relationships in Concerted Cycloaddition Reactions, Hoffmann, R; Woodward, R.B., J.Am.Chem.Soc. 1965, 87 4388-4389.

[5] Table of Interatomic Distances and Configuration of Molecules and Ions, No. 11. Supplement 1956–1959, Chemical Society, London, 1958.

[6] Summary of Energies, Year 3 Computational Manual, Imperial College London.