Rep:Mod:PAP0803

Module 3

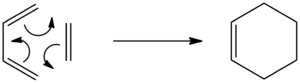

The Cope Rearrangement

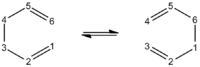

The mechanism of a reaction can be studied using computational methods. In this tutorial, the Cope rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene will be studied to find the low energy minima and transition structures on the C6H10 potential energy surface which will indicate the mechanism of the reaction. This reaction is a [3,3]-sigmatropic shift rearrangement, an example of a pericyclic reaction, which occurs via a "chair" or a "boat" transition structure and involves the concerted breaking and formation of a σ bond.

|

|

Optimising the Reactants and Products

The structures of the reactants and products will be optimised, symmetrised to find their point groups, analysed using vibrational frequencies, and their potential energies corrected so they can be compared with experimental values.

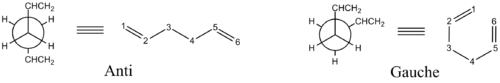

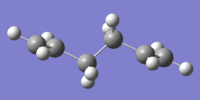

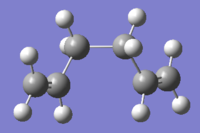

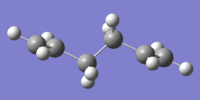

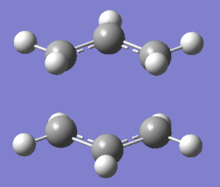

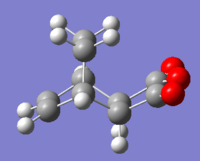

There are two possible conformers for 1,5-hexadiene molecule; "anti" and "gauche". The four central carbon atoms, C2 to C5, are in an anti-periplanar arrangement with the dihedral angle at 180o in the anti conformer. In the gauche conformer, the molecule is arranged such that the terminal double bonds are facing each other. The Newman projections for both conformers can be seen on the right.

The "anti" and gauche" 1,5-hexadiene will be optimised using the Hartree-Fock and the DFT B3LYP methods and compared with each other to find the minimum energy conformation. First the "anti" conformer was drawn in Gaussian, cleaned, and optimised using the Hartree-Fock 3-21G method. This method is based on the Schrodinger equation and the basis set determines the orbitals of the molecules. The memory limit was set to 250MB and the calculation was run.

The energy of the optimised molecule was recorded and the point group found using the 'Symmetrize' function.

The "gauche" conformer was optimised next using the same method as the optimisation for the "anti" conformer. The anti structure is expected to be the lowest energy conformer because the two large terminal carbon alkenes are the furthest away from each other in this form and therefore steric repulsion is decreased.

The energy for the optimised gauche conformer was recorded and the point group was found. As there are many different gauche and anti conformations possible for this molecule, a few different structures were optimised and compared with the results from Appendix 1. The results are summarised in Table 1:

| Conformer | Image | Point Group | Energy (a.u.) | Energy (kJmol-1) | DOI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti2 |  |

Ci | -231.69254 | -6.08309x105 | DOI:10042/to-11464 |

| Anti3 |  |

C2h | -231.68907 | -6.08300x105 | DOI:10042/to-11465 |

| Gauche4 |  |

C2 | -231.69153 | -6.08306x105 | DOI:10042/to-11466 |

| Gauche2 |  |

C2v | -231.69167 | -6.08306x105 | DOI:10042/to-11467 |

The gauche conformers are 2.65kJmol-1 more stable than the anti2 conformer however this is within the error limit of the program so the more stable conformer can not be identified using this method. The stability of the gauche conformers may be explained as being due to electronic interactions between the π orbitals of the double bonds. The orientation of the bonds allow the orbitals to interact, stabilising the molecule more than the steric clash destabilises it causing an overall stabilisation.

The structures in Table 1 were compared with those in the table in Appendix 1 and the anti conformer was found to be the same as anti2. The gauche conformer is the same as gauche4. The final energy of the anti2 form calculated is the same as that given in the table and the point groups are also the same therefore the correct anti structure has been found.

Optimisation of Anti2 with HF and DFT Methods

The optimisation of the anti conformer was run again using the DFT B3LYP method and 6-31g(d) basis set. This is a higher level of theory therefore it should give a more accurate optimisation of the structure. The results are summarised in Table 2 below.

| Method | Basis Set | Image | Point Group | Energy (a.u.) | Energy (kJmol-1) | DOI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hartree-Fock | 3-21g |  |

Ci | -231.69254 | -6.08309x105 | DOI:10042/to-11464 |

| DFT B3LYP | 6-31g(d) |  |

C2 | -234.61170 | -6.08097x105 | DOI:10042/to-11469 |

The geometries of the structures have not changed by much however the energy from the DFT optimised conformer is 212.24kJmol-1 lower than the Hartree-Fock optimised molecule is expected as it uses a higher level of theory. However, energies obtained from optimisation using different methods and basis sets can not be compared as different calculations are used.

The geometry of the molecule must be compared in order to find the best optimised structure:

| Before Optimisation | HF/3-21G | B2LYP/6-31G(d) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| C=C bond/Å | 1.355 | 1.316 | 1.334 |

| Central C-C bond/Å | 1.540 | 1.553 | 1.548 |

| =C-C bond/Å | 1.540 | 1.509 | 1.504 |

| =C-H bond/Å | 1.070 | 1.075 | 1.089 |

| C-H bond/Å | 1.070 | 1.085 | 1.098 |

| C=C-C angle/o | 120.0 | 124.8 | 125.3 |

| C-C-C angle/o | 109.5 | 111.3 | 112.7 |

The bond lengths and angles show that the B3LYP/6-31G(d) method is the best optmisation method.

Frequency Calculation

To confirm that the global minimum of the potential energy surface has been found, frequency calculations must be performed. If all the frequencies reported are real and positive, the minimum has been found. This also allows comparison of the energies with experimental energies, such as the electronic, thermal, zero point and free energies.

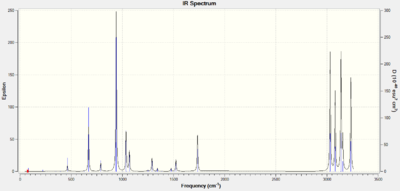

The IR analysis was carried out on the anti2 conformer and the IR spectrum can be seen below. It shows that all the frequencies are positive which means the minimum energy structure been found.

The thermochemistry data from the output .log file shows the different energies of the molecule which are summarised in Table 4.

| Energy | Energy/ a.u. | Energy/ kJmol-1 |

|---|---|---|

| Sum of electronic and zero-point energies | -234.469204 | -6.15599x105 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal energies | -234.461857 | -6.15580x105 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal enthalpies | -234.460913 | -6.15577x105 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal free energies | -234.500778 | -6.15682x105 |

The sum of the electronic and zero-point energies are the electronic and vibrational energies at 0K. The sum of the electronic and thermal energies are at 298.15K and 1atm of pressure. This includes translational, vibrational and rotational modes of energy. The electronic and thermal enthalpies has the correction for enthalpy, and the sum of the electronic and thermal free energies has the contribution from the entropy to the free energy. The values in the table above can be compared with experimental data.

Optimising the "Chair" and "Boat" Transition Structures

The transition state of the Cope rearrangement is either a chair structure or a boat structure. To find which which of the two transition states occur, they must both be optimised and their energies compared. The chair TS can be optimised using two methods;

- 1. The Hartree-Fock method and 3-21g basis set

- 2. The Frozen Coordinate Method

The boat TS can be optimised using the QST2 method.

Optimisation of the Chair TS structure using the HF/3-21g method

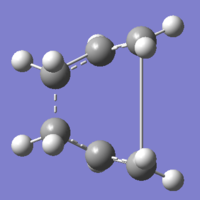

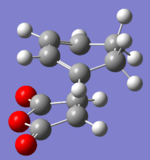

The allyl fragment (CH2CHCH2) was optimised using the Hartree-Fock method and the 3-21g basis set. Two of the optimised structures were then built to look like the transition state and arranged so the bond distance between the two terminal carbons of the allyl fragments were about 2.2Å. The optimisation was carried out with the Job Type as Opt+Freq, optimising to a TS(Berny). The additional keywords added were Opt=NoEigen which prevents the calculation from failing if more than one negative frequency is found in the calculation.

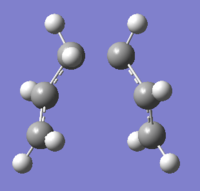

|

|

The frequency analysis of the optimised molecule shows a negative frequency at -817.94cm-1;

|

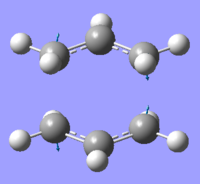

This is an imaginary frequency which corresponds to the Cope rearrangement. The animation of this vibration shows that the Cope rearrangement happens in a concerted fashion with one bond breaking while the other is forming.

|

|

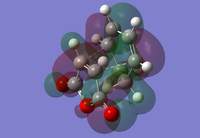

Optimisation of the Chair TS Structure using the Frozen Coordinate Method

This method allows the bond length between the two terminal carbons of the allyl molecules to be set to 2.2Å during the first optimisation using the HF/3-21G method and basis set. The bond lengths were then unfrozen and the optimisation to a transition state was run again using the TS(Berny) method. This was done using the redundant coordinate editor. The optimised structure can be compared with the optimised structure from the first optimisation.

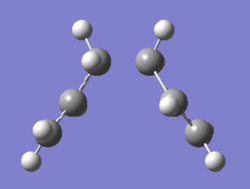

|

|

|

The bond length between the two terminal carbons for the frozen coordinate method is only slightly shorter than that for the Hartree-Fock method. The frequency analysis also shows an imaginary frequency at -818.02cm-1 which corresponds to the C-C bond breaking and bond forming between the two allyl fragments.

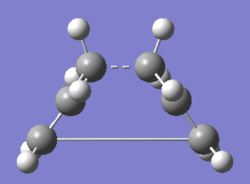

Optimisation of the Boat TS Structure using the QST2 Method

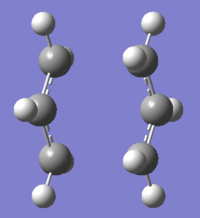

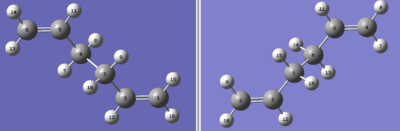

The QST2 method was used to investigate the boat transition structure. This involves specifying the reactant and product molecules so the calculation can interpret the transition structure. The anti2 molecule was opened in a new GaussView window and a second anti2 molecule was added to the molecular group. These were numbered in the same way to make sure a valid transition state is found.

|

|

Both the carbon atoms and the hydrogen atoms were numbered the same in both the reactant and the product molecule. The calculation was run using the Opt+Freq job type and optimisation to a QST2 using the HF/3-21G method and basis set. The initial calculation failed as it looked like a dissociated form of the chair TS.

This is because only the top allyl fragment was translated so the optimisaton was not carried out properly. The reactant and product molecule geometries were rearranged so the central C-C-C-C dihedral angle was set to 0o and the inside C-C-C angle was set to 100o, with the carbon and hydrogen atoms still corresponding to each other.

The optimisation was run again using the same method as the first but using the rearranged reactant and product molecules.

The second optimisation was successful and the resulting energy was -231.602802a.u. which is equivalent to 6.081x105 kJmol-1. It can be seen that this calculation was more successful than the first as both allyl fragments were taken into account.

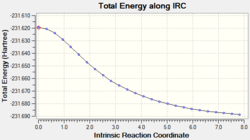

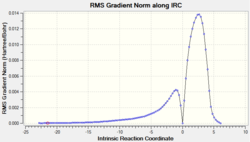

Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate Method

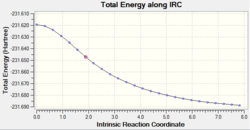

It is difficult to determine which of the transition structures is formed in the reaction just by looking at the optimised molecule so the IRC must be found. An intrinsic reaction coordinate was carried out for both the chair and boat transition states. As the reaction is symmetrical, the IRC was calculated in only the forward reaction. The force constants were set to be calculated once at the beginning of the calculation and the number of additional points was set to 50.

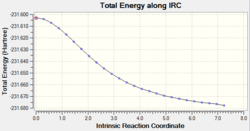

Chair

The IRC calculation showed 26 intermediate geometries. The graphs for the total energy and RMS gradient can also be seen below.

|

|

|

The minimum energy point on the total energy graph has not been reached and the gradient does not reach zero therefore the minimum energy conformation has not been reached. In order to find the minimum energy structure, three different methods can be used;

- 1. The last point on the IRC can be run using a normal optimisation

- 2. The IRC is restarted using a greater number of additional points

- 3. The IRC can be redone computing the force constants at every step

Method 1:

The HF/3-21G method and basis set was used to optimised the last conformation of the IRC calculation.

|

|

This optimisation only created a slightly lower energy conformation but it did not give the minimum energy structure.

Method 2:

Again, the optimisation was set up using the same method as before but with a greater number of additional points.

|

|

|

The graphs show that the energy is lower and the RMS gradient is closer to zero but the minimum energy structure still has not been reached.

Method 3:

The optimisation was set up calculating force constants at every step.

|

|

|

This method optimises the structure closer to the minimum energy structure as can be seen by the graphs. A summary of the energies, gradients and bond parameters can be seen on the table below.

| IRC | IRC Method 1 | IRC Method 2 | IRC Method 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy/ a.u. | -231.688 | -231.692 | -231.689 | -231.692 |

| Energy/ kJmol-1 | -6.083x105 | -6.081x105 | -6.083x105 | -6.083x105 |

| Gradient/ a.u. | 0.00070686 | 0.00000285 | 0.00070686 | 0.00001152 |

| C1-C6 bond breaking length/Å | 3.33 | 4.39 | 3.33 | 4.36 |

| C3-C4 bond forming length/Å | 1.56 | 1.55 | 1.56 | 1.55 |

| Internal C-C bond length/Å | 1.32 | 1.51 | 1.32 | 1.51 |

| C-H bond length/Å | 1.07 | 1.09 | 1.07 | 1.07 |

| C-C-C bond angle/o | 124.29 | 124.98 | 124.29 | 124.99 |

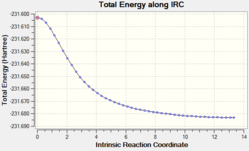

Boat

The same IRC calculation was carried out on the boat transition structure and the results can be seen below. There were 26 intermediate geometries for the calculation.

|

|

|

As with the chair structure, this calculation does not give the minimum energy structure. This is seen in the total energy graph which does not reach the minimum energy point and the RMS gradient graph does not reach zero.

Method 1:

The final structure in the transition series was optimised using the HF/3-21G method. The results can be seen below.

|

|

The optimised structure does not look much like the boat transition state which means this method of optimisation did not produce better results.

Method 2:

The optimisation was set up again using 150 additional points instead of 50. This calculation also produced 26 intermediate geometries and is very similar to the first IRC calculation run.

|

|

|

This still did not produce a better minimum energy structure so the third method was run.

Method 3:

The IRC calculation was set up to calculate force constants at every step. The calculation was only carried out in the forward direction and the animation and graphs can be seen below. This time 47 points were calculated along the IRC.

|

|

|

The graphs clearly show that a lower energy structure has been found. The structures found using all three methods are very similar but the third method is the most accurate for the calculation of the transition state.

| IRC | IRC Method 1 | IRC Method 2 | IRC Method 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy/ a.u. | -231.603 | -231.683 | -231.678 | -231.683 |

| Energy/ kJmol-1 | -6.081x105 | -6.083x105 | -6.083x105 | -6.083x105 |

| Gradient/ a.u. | 0.00002108 | 0.00001917 | 0.00096122 | 0.00000573 |

| C1-C6 bond breaking length/Å | 3.37 | 4.36 | 3.38 | 4.34 |

| C3-C4 bond forming length/Å | 1.59 | 1.58 | 1.59 | 1.58 |

| Internal C-C bond length/Å | 1.32 | 1.32 | 1.32 | 1.32 |

| C-H bond length/Å | 1.07 | 1.09 | 1.07 | 1.07 |

| C-C-C bond angle/o | 124.12 | 124.40 | 124.12 | 124.44 |

Activation Energies

Both the chair and boat Hartree-Fock optimised structures were re-optimised using the higher level, more accurate B3LYP/6-31G(d) method and basis set. The vibrational analysis was also carried out for this method and the thermochemistry data from the two methods are compared in the table below.

| HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic Energy | Sum of Electronic and Zero-point Energies | Sum of Electronic and Thermal Energies | Electronic Energy | Sum of Electronic and Zero-point Energies | Sum of Electronic and Thermal Energies | |

| Chair TS DOI:10042/to-11503 | -231.619322 | -231.466699 | -231.461340 | -234.556983 | -234.4134931 | -234.409010 |

| Boat TS DOI:10042/to-11500 | -231.602802 | -231.450927 | -231.445297 | -234.543093 | -234.402340 | -234.396006 |

| Reactant (Anti2) DOI:10042/to-11469 | -231.692535 | -231.539539 | -231.532565 | -234.611710 | -234.469204 | -234.461857 |

1 a.u. = 627.509kcalmol-1. The DOIs given are for the B3LYP/6-31G(d) optimised structures.

| HF/3-21G at 0K | HF/3-21G at 298.15K | B3LYP/6-21G* at 0K | B3LYP/6-21G* at 298.15K | Experimental at 0K [1] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔE Chair | 45.71 | 44.69 | 34.96 | 33.16 | 33.5 ± 0.51 |

| ΔE Boat | 55.60 | 54.76 | 41.96 | 41.32 | 44.7 ± 2.0 |

The difference in energy between the chair TS and the reactant is smaller than the energy difference between the boat TS and the reactant. This suggests that the Cope rearrangement occurs via the chair transition state as it is lower in energy than the boat transition state. The differences in energy for the chair transition state is closer to the experimental values which further supports the fact that the reaction occurs through the chair transition state. The B3LYP method of calculation is better than the Hartree-Fock method as it uses a higher level of computation. Therefore it gives a better approximation for the transition state than the HF method.

References

- ↑ Wiest, O.; Black, K.A.; Houk, K.N., J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1994, 116, 10336-10337 DOI:10.1021/ja00101a078

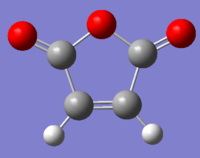

Diels-Alder Cycloaddition

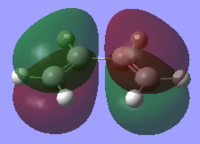

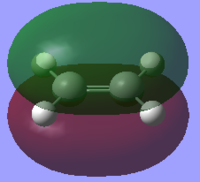

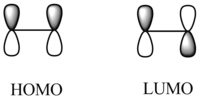

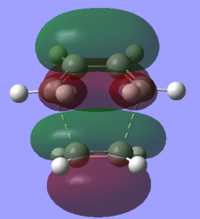

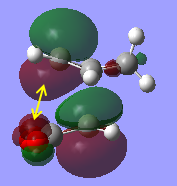

Diels-Alder cycloaddition is also an example of a pericyclic reaction as it involves the concerted breaking and forming of two π bonds. These reactions can either be forbidden or allowed according to the relative symmetries of the HOMO and LUMO of the reactant molecules. When the orbitals are not of the same symmetry, i.e. they are asymmetric to each other, the reaction is forbidden. If the orbitals are of the same symmetry, the reaction is allowed.

Reaction of Cis-Butadiene and Ethene

Optimisation of the Reactant Molecules

A molecule of cis-butadiene and a molecule of ethene were drawn using GaussView in separate windows, adjusted using the "Clean" function and optimised using the semi-empirical AM1 method. The point group of cis-butadiene was found to be C2v and ethene has a point group of D2h therefore they both have a σv plane of symmetry.

|

|

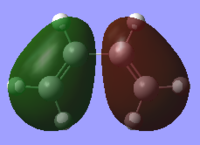

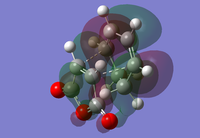

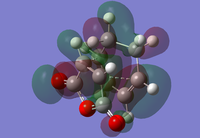

The HOMOs and LUMOs for both molecules were also found to ensure the molecules were completely symmetrical. These can be compared with the HOMOs and LUMOs of both molecules found from the LCAO method. As can be seen from the frontier molecular orbital method (FMO), the HOMO of cis-butadiene is antisymmetric and the LUMO is symmetric whereas the HOMO of ethene is symmetric and the LUMO is antisymmetric. This corresponds to an allowed reaction because in order for the reaction to take place, the HOMO of one molecule must interact with the LUMO of the other.

|

|

|

|

|

|

The HOMOs and LUMOs of the optimised reactant molecules are very similar to those predicted by LCAO using the FMO method with the exception of the cis-butadiene LUMO. The computationally generated LUMO shows the central two pi orbitals are in the same orientation whereas the LCAO LUMO predicts that these orbitals should be oppositely orientated.

Determination of Transition State

The transition state of the Diels-Alder reaction was determined by appending both reactant molecules into a window in GaussView and were arranged in a "guess" transition structure based on an envelope structure. The molecule was optimised using the Frozen Coordinate method by setting the bond distance between the terminal carbons of the ethene and butadiene molecules to 2.2Å and running the calculation. The calculation was then run again minimising to a TS(Berny) this time in order to find the lowest energy structure.

To see if the transition state had been found a vibrational analysis was carried out. The analysis showed one imaginary frequency at -818cm-1 which corresponds to the concerted reaction. The lowest positive frequency at 166.55cm-1 can also be found from the vibrational analysis.

|

|

The imaginary frequency show the symmetric concerted formation of the new σ C-C bonds. The lowest positive frequency is very different to the imaginary frequency, showing a twisting motion of the -CH2-CH2- bond in an asynchronous manner with bond formation and bond breaking occurring alternatively.

| Parameter | |

|---|---|

| Energy/ a.u. | -231.603209 |

| Energy/ kJmol-1 | -6.08074x105 |

| Gradient/ a.u. | 0.00002935 |

| Bond Forming Distance/Å | 2.21 |

| Central C-C bond/Å | 1.39 |

| Angle of Bond Formation/o | 101.61 |

The Van der Waals radii of simple carbon-based molecules is 1.70Å[1] which indicates that there is interaction between the two molecules. The average sp2 carbon bond length is 1.34Å[2] and is 1.54Å[3] for sp3 hydbridised carbons. The bond distance between the two reactant molecules is 2.21Å which is greater than the average C-C single bond length but less than the Van der Waals radius for two carbon atoms at 3.40Å. As the bond length for the transition structure is between the two, it can be determined that the carbon is neither sp2 nor sp3 hybridised but is somewhere between the two which confirms that the transition structure had been found.

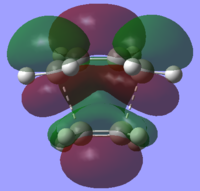

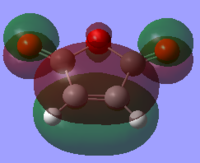

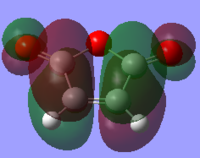

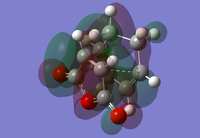

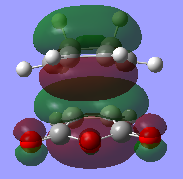

The HOMO and LUMO of the transition structure give information on the bond forming process.

|

|

It can be seen that the HOMO of the transition state is antisymmetric whereas the LUMO is symmetric. This corresponds to the asymmetric HOMO of the cis-butadiene molecule interacting with the asymmetric LUMO of the ethene molecule. The LUMO is symmetric and is a result of the interaction between the symmetric LUMO of the cis-butadiene molecule and the HOMO of the ethene molecule.

References

- ↑ Stoicheff, B.P., Tetrahedron, 1962, 17, 135-145 DOI:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)99013-1

- ↑ A. Bondi, J. Phys. Chem., 1964, 68:3;DOI:10.1021/j100785a001

- ↑ Online CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 92nd edition, 2012

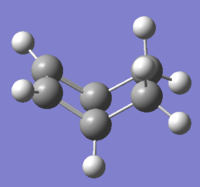

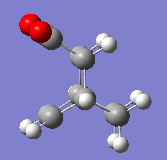

Reaction of Cyclohexa-1,3-diene and Maleic Anhydride

Diels-Alder Reactions can be regioselective when the diene and dienophile are substituted, as seen in the reaction between cyclohexa-1,3-diene and maleic anhydride. In this case there are two possible products, an endo isomer and an exo isomer, which are the result of the alignment of the molecules during the reaction. It is expected that the endo product is higher in energy as this is the kinetic product, whereas the exo product is lower in energy as it is the thermodynamically more favourable product. Although the exo product is the more thermodynamically favourable product, this is not formed because the activation barrier of the transition state is too high.

Optimisation of the Reactants

In order to find an ideal transition state, the reactant molecules had to first be optimised. This was done by drawing the molecules in GaussView, using the "Clean" function and submitting the calculation to run as an optimisation using the semi-empirical AM1 method.

|

|

The HOMO and LUMO of both molecules were calculated and it was found that the HOMO of the cyclohexa-1,3-diene is antisymmetric that of the maleic anhydride is symmetric. On the other hand, the LUMO of cyclohexa-1,3-diene is symmetric and the LUMO of maleic anhydride is antisymmetric. As with the first Diels-Alder reaction, the HOMO of one reactant interacts with the LUMO of the other reactant, therefore as the HOMO/LUMO pair of the cyclohexa-1,3-diene are of the same symmetry, the reaction is allowed. Diels-Alder reactions are favoured by the orbital interaction between the HOMO of the diene and the LUMO of the dienophile.

|

|

|

|

Determining Transition Structures

Initially, the transition structures for the exo and endo products were carried out using the QST2 method therefore the product molecules of both had to be optimised using the AM1 semi-empirical method.

|

|

The QST2 method was run by numbering the carbon and oxygen atoms in the reactant molecules and numbering the corresponding atoms in the product molecules in the same way. The optimisation and frequency calculation was run by optimising to a TS(QST2) and the .fchk file showed that the transition structures appeared to have been found.

|

|

However, the imaginary frequency could not be found on either of the checkpoint files which suggests that the calculation had not run properly. This may have been because the molecules were not entirely symmetric so it would not give an imaginary frequency corresponding to the synchronous bond formation.

Therefore the frozen coordinate method was used to find the transition states. The redundant coordinate function was used to set the bond distance between the two reactant fragments to be 2.2Å and the calculation was run as a normal optimisation. The bonds were then unfrozen and the calculation run again with Opt+Freq as the job type and by optimising the structure to a TS(Berny) using the semi-empirical AM1 method.

|

|

|

|

The results show that there is an imaginary frequency at -812.25cm-1 for the exo transition state which corresponds to the concerted formation of the bonds. The imaginary frequency for the endo transition state occurs at a slightly lower value of -806.51cm-1 however this also corresponds to the concerted bond formation between cyclo-1,3-hexadiene and ethene.

The geometries of the transition states and analysis of the HOMO and LUMO molecular orbitals allow us to determine which of the two transition states is more stable and why. A summary of the parameters for both the exo and the endo transition states can be seen in Table 10.

| Parameter | Exo | Endo |

|---|---|---|

| Energy/ a.u. | -0.050420 | -0.051505 |

| Energy/ kJmol-1 | 132.38 | 135.23 |

| Gradient/ a.u. | 0.00000243 | 0.00000507 |

| C-C Bond Forming Length 1/Å | 2.17 | 2.16 |

| C-C Bond Forming Length 2/Å | 2.17 | 2.16 |

| Maleic Anhydride -(C=O)-O-(C=O)- Length/Å | 2.28 | 2.28 |

| Cyclohexadiene C=C Bond Length 1/Å | 1.39 | 1.39 |

| Cylcohexadiene C=C Bond Length 2/Å | 1.39 | 1.39 |

| -(C=O)-O-(C=O)- and Opposite Carbon Bond Length 1/Å | 2.95 | 2.89 |

| -(C=O)-O-(C=O)- and Opposite Carbon Bond Length 2/Å | 2.95 | 2.89 |

The table shows that the exo transition state is about 2.85 kJmol-1 higher in energy than the endo isomer. This is expected as there are secondary orbital interactions between the orbitals of the -(C=O)-O-(C=O)- bonds in maleic anhydride and the -CH=CH- orbitals of the cyclohexa-1,3-diene which weakens the C=C bond. This is only seen in the endo transition state as the -CH=CH- is too far in the exo structure for there to be significant orbital overlap.

|

|

|

|

The HOMOs and LUMOs for both the endo and exo transition states are all antisymmetric which is a result of the antisymmetric cyclohexa-1,3-diene HOMO interacting with the antisymmetric maleic anhydride LUMO. The HOMOs and LUMOs of both the exo and endo transition state look very similar which is to be expected.

The HOMO for the endo transition state is supposed to show both primary and secondary orbital interactions however this is not seen. Therefore the HOMO-1 orbital was looked at and it shows a slight interaction between the orbitals in question. This may be because the method of calculation is too low in complexity so, with more time and greater computational power, a higher level of theory could be used which may give a better representation of the secondary orbitals of the endo HOMO.

|

|

Another factor which contributes to the stability of the endo transition structure is the lack of steric repulsion that is present in the exo transition structure. The exo structure is more strained due to steric clashes between the -CH-CH- fragment and the maleic anhydride which decreases the stability of the exo structure compared to the endo.

To find a better approximation of the transition states, IRC calculations were run on both the exo and endo transition states. Unlike the formation of the chair and boat transition states, this reaction is not symmetric therefore the IRC has to be run in both directions. The force constants were calculated at every step of the calculation and the number of points was set to 100 points. The exo transition state produced 110 intermediate geometries and the endo transition state produced 124 intermediate geometries. The last points on both IRC calculations show the product molecules as the calculation was run in both directions.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The IRCs of both transition states are very similar with the total energy graphs showing the energy decreasing in negativity to the transition state and then decreasing again until the product molecule has been formed. The RMS gradient graphs show the gradient decreasing to zero before increasing again. The intermediate geometry of this point correspond to the highest point of the total energy graph which correspond to the transition states. The total energy graph of the exo isomer shows a more negative final state than the endo which confirms that the exo transition state is higher in energy.

Conclusion

Transition structures can be accurately modeled using computational methods and predicting the molecular orbitals. The MOs generated can then be used to predict which molecular orbitals of the reactants overlap with each other according to their symmetry. The Diels-Alder reaction between cis-butadiene and ethene is simpler than the reaction between cyclohexa-1,3-diene and maleic anhydride so it gives good approximations with methods at lower levels of theory. However, a more complex method is needed for the second Diels-Alder reaction as the structures must be properly optimised and placed for the transition states to be found.