Rep:Mod:OrgDC

Introduction to Molecular Mechanics

Quantum mechanics offers us a rigorous and detailed description of a molecules structure and electronics. However these calculations requires a lot of computer power, and so usually take a long time to run even for small molecules. With larger and more complicated molecules being synthesised, using Quantum mechanics is unviable. There lies the birth of Molecular mechanics, using 'force-field' methods to generate molecules for conformational analysis. This was derived from vibrational spectroscopy to obtain a molecules behaviour. Molecular Mechanics also uses the Born-Oppenheimer approximation which states that when the nuclei vibrate/move, there is a constant electron density around it and so the atoms are considered as spheres. The motions of these spheres are then modelled using classical mechanics which allows analysis of much grander molecules for which otherwise could not have been made. It is important to note that this method is only valid for molecules in the ground state as the energy of the electrons in the molecule have not been explicitly measured. [1]

Dimerisation of Cyclopentadiene

The dimerisation of cyclopentadiene is a π4s + π2s cycloaddition, also known as a Diels-Alder reaction. Under thermal conditions this 6π-electron pericyclic reaction goes via a Huckel transition state in which the overlap of each molecules frontier orbitals must combine suprafacially.[2] Scheme 1 shows the mechanism of the dimerisation, and shows the concerted formation of two σ-bonds between the termini of a conjugated п-system. This results in the formation of two conformational isomers, an Endo and Exo product.

Here Molecular Mechanics was used to observe which of the two conformers is the most thermodynamically stable. These structures were optimised using the MMFF94s force field using the Avogadro program. The results are shown below.

| Endo | Exo | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure |

|

| ||||||

| Total Bond Stretching Energy kcal/mol | 3.46793 | 3.54309 | ||||||

| Total Angle Bending Energy kcal/mol | 33.18933 | 30.77256 | ||||||

| Total Torsional Energy kcal/mol | -2.94950 | -2.73051 | ||||||

| Total Van Der Waals Energy kcal/mol | 12.35873 | 12.80127 | ||||||

| Total Electrostatic Energy kcal/mol | 14.18455 | 13.01366 | ||||||

| Total Energy kcal/mol | 58.19067 | 55.37342 |

From the results shown in the table above one can tell that the most thermodynamically stable conformer is the Exo product, however this is the minor product in this reaction and it is the Endo conformer is which mostly observed. This would suggest that the Endo conformer has a much lower transition energy that compared to the Exo conformer. This would also suggest that the reaction is under kinetic conditions, to obtain the least thermodynamically stable conformer.[3]

Hydrogenation of an endo cyclopentadiene dimer

Hydrogenation of dicyclopentadiene has been found to proceed via consecutive reactions as shown by reaction (1) in Scheme 2. [4]

The objective is to use computational methods to find out why the reaction goes via reaction 2 and not reaction 1. This was done by optimising each molecule using the MMFF94s force field in the avagadro programme, the results are shown below.

| Molecule 3 | Molecule 4 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure |

|

| ||||||

| Total Bond Stretching Energy kcal/mol | 3.31167 | 2.82306 | ||||||

| Total Angle Bending Energy kcal/mol | 31.93492 | 24.68553 | ||||||

| Total Torsional Energy kcal/mol | -1.46978 | -0.37812 | ||||||

| Total Van Der Waals Energy kcal/mol | 13.63841 | 10.63689 | ||||||

| Total Electrostatic Energy kcal/mol | 5.11949 | 5.14702 | ||||||

| Total Energy kcal/mol | 50.44565 | 41.25794 |

As one can tell both hydrogenation products have lowered the overall energy of the Endo cyclopentadiene dimer. Added to this stabilisation, the energy of product 4 is 9.18771 kcal/mol lower in energy than product 3. This can be explained by looking at the break down of energies. The total bond stretching energies, Van der waals energies and Electrostatic energies are relatively similar, however, there is significant difference in the torsion and total angle bending energies. This can be shown by measuring the bond angles at the carbon-carbon double bond.In molecule 3 the double bond is located on a 6-membered ring which is bridged and hence held in a boat conformation. The carbon in the double bond is sp2 hybridised and so will want to have a bond angle of 120 degrees, measuring this angle it is determined to be 107.4 degrees. If one then looks are the carbon double bond on molecule 4 and compare, it is determined that the bond angle at the double bond is 112 degrees, much close to the preferred 120. This shows that molecule 3 has an increase in angle bending and torsional strain and hence is higher in energy. One can conclude that this reaction proceeds thermodynamically and is observed experimentally.[4]

In the synthesis of Taxol there is a key intermediate which displays atropisomerism. Atropisomerism is a term used to describe stereoisomers where the steric barrier prevents rotation about a single bond and allows the separation and isolation of each conformer.[5]

Here the energies of both isomers are explored and its various conformational energies. As molecular mechanics hunt for an energy minima, when looking at the conformers of the cyclohexane ring, the minima's are the chair and twist boat conformers and hence these arrangements will be calculated for each isomer.

| chair 1 | chair 2 | twist boat 1 | twist boat 2 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure |

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Total Bond Stretching Energy kcal/mol | 7.67010 | 8.16693 | 7.95023 | 8.34381 | ||||||||||||

| Total Angle Bending Energy kcal/mol | 28.32839 | 34.20405 | 29.70185 | 34.34710 | ||||||||||||

| Total Torsional Energy kcal/mol | 0.23165 | 3.66550 | 2.60101 | 6.53842 | ||||||||||||

| Total Van Der Waals Energy kcal/mol | 33.10900 | 34.70805 | 34.67148 | 36.74761 | ||||||||||||

| Total Electrostatic Energy kcal/mol | 0.30433 | 0.19756 | 0.32154 | 0.15142 | ||||||||||||

| Total Energy kcal/mol | 70.54391 | 82.68428 | 76.28717 | 88.16028 |

As expected for molecule 9 the lowest energy is in the chair conformation. Chair 1 is of a lower energy than chair 2, this is due to the ring with the carbonyl in the equatorial position, whereas in chair 2 it is axial. There is also a large difference in torsional and angle bending energy. What is also interesting is the twist boat 1 being of lower energy than the chair 2 conformation. This was due to a reduction in angle bending, torsion and electrostatic energy.

| chair 1 | chair 2 | twist boat 1 | twist boat 2 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure |

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Total Bond Stretching Energy kcal/mol | 7.59254 | 8.62584 | 7.72694 | 8.93665 | ||||||||||||

| Total Angle Bending Energy kcal/mol | 18.81834 | 27.76132 | 19.61578 | 24.20491 | ||||||||||||

| Total Torsional Energy kcal/mol | 0.23291 | 6.32984 | 3.20838 | 8.16656 | ||||||||||||

| Total Van Der Waals Energy kcal/mol | 33.25730 | 36.17448 | 35.01900 | 38.08010 | ||||||||||||

| Total Electrostatic Energy kcal/mol | -0.05388 | 0.41759 | -0.04671 | 0.52724 | ||||||||||||

| Total Energy kcal/mol | 60.55061 | 74.74383 | 66.32028 | 81.49468 |

The conformer energies show a similar trend to that of intermediate 9.

Of both intermediates the chair conformation was the lowest energy conformer form. Intermediate 10 was 9.9933 kcal/mol lower in energy than intermediate 9. This was found to be caused by a large difference in angle bending and electrostatic energies.

Carbon-Carbon double bond chemistry usually reacts via electrophilic addition and results in the formation of a carbocation. This is the rate determining step, and so the stability of the carbocation will determine the rate of reaction. To explore this the hydrogenation of the double bond in molecule 10 will be investigated. Upon formation of the carbocation, there are two positions for which the charge can be placed. One is a tertiary carbon, and one is a secondary. Usually we predict that the tertiary position to be very stable due to an increased number of sigma-conjugation interactions than compared with the secondary or primary ions. And so one can presume that in this senario, the positive charge will sit on the tertiary carbon and be quite stable. However, experimentally the rates of reactions are very slow, suggesting that the ion intermediate is not as stable as first assumed. it would also be assumed that the rates of reaction to be fast as forming the sigma framework with no double bonds would be predicted to release bond strain which was held in the pi-system, but this is also not observed experimentally.

| Structure |

| |||

| Total Bond Stretching Energy kcal/mol | 6.42356 | |||

| Total Angle Bending Energy kcal/mol | 22.28890 | |||

| Total Torsional Energy kcal/mol | 9.19307 | |||

| Total Van Der Waals Energy kcal/mol | 31.29904 | |||

| Total Electrostatic Energy kcal/mol | 0.00000 | |||

| Total Energy kcal/mol | 69.53463 |

Usually double bonds on a bridgehead ring system can not form. This is due to the double bond exhibiting 'trans' like character, and would increase the overall energy of the molecule due to torsional, bond and angle strains. Furthermore the P-orbital which would form the double bond will not be correctly aligned to do so.[6] Intermediate 10 can form the double bond adjacent to a bridgehead because the ring is large (9/10-membered) and so the strain is reduced and so complies with bredt's rule.

From the data shown we can see that the hydrogenated product of intermediate 10 is of higher energy than that of its olefin. This is unusual as we would expect a decrease in bond strain and hence and increase in stability. This has formed a new group of compounds known as 'hyperstable' olefins, and are said to have negative olefin strain energies. [7] As the ring size is increased the preferred angle increases. sp3 hybridised carbons prefer to be 109.5 degrees, however as the ring size is increased above a 6 membered ring, it is no longer stable and becomes under increasing strain, whereas sp2 carbons prefer an angle of 120 degrees and so the increase in ring size accommodates this. Not only is the groud state of the olefin have an increase in stability, but the transition state becomes significantly unstable and much higher in energy, leading to an increase in activation energy and hence a slower reaction takes place. This is due to the instability of the carbocation, it has a lack of sigma-conjugation on both the tertiary carbon and secondary carbon in the opened double bond system, because the orbital which contains the charge is not correctly aligned with the sigma-orbitals around it. These reasons show a slow rate of reaction of the intermediate 9 and 10 olefins. [8]

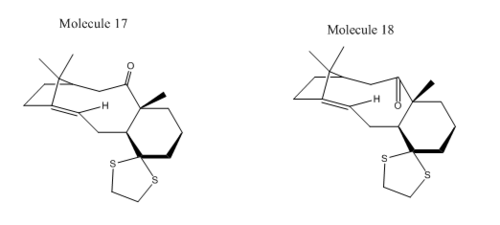

| 17 | 18 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure |

|

| ||||||

| Total Bond Stretching Energy kcal/mol | 15.72501 | 15.03408 | ||||||

| Total Angle Bending Energy kcal/mol | 32.01333 | 30.98498 | ||||||

| Total Torsional Energy kcal/mol | 11.33804 | 9.64244 | ||||||

| Total Van Der Waals Energy kcal/mol | 51.49699 | 49.26508 | ||||||

| Total Electrostatic Energy kcal/mol | -7.59336 | -6.05929 | ||||||

| Total Energy kcal/mol | 104.30679 | 100.45304 |

As intermediate conformer 18 was found to be the most stable, this will be the dominant conformer and hence the NMR was calculated and compared to literature as shown below.

Molecule 17:DOI:10042/26727 Molecule 18:DOI:10042/26702

| Spectrum | Computational (δ ppm) | Experimental (δ ppm) [9] |

|---|---|---|

|

6.00 (1H, s) | 5.21 (1H, m) |

| 3.14 (2H, s) | 2.70-3.00 (6H, m) | |

| 3.00 (1H, s) | ||

| 2.93 (2H, s) | ||

| 2.82 (2H, s) | ||

| 2.62 (1H, s) | 2.35-2.70 (4H, m) | |

| 2.56 (1H, s) | ||

| 2.48 (1H, s) | ||

| 2.34 (2H, s) | 1.70-2.35 (6H, m) 1.58 (1H, t) | |

| 2.28 (1H, s) | ||

| 2.00 (2H, s) | ||

| 1.85 (2H, s) | ||

| 1.66 (1H, s) | 1.20-1.50 (3H, m) | |

| 1.59 (1H, s) | ||

| 1.52 (2H, s) | ||

| 1.37 (1H, s) | 1.1 (3H, s) | |

| 1.31 (1H, s) | ||

| 1.23 (2H, s) | 1.07 (3H, s) | |

| 0.96 (3H, s) | 1.03 (3H, s) | |

| 0.63 (1H, s) |

It is always important to measure ones computational measurements against experimental, this is a good indication of how well the molecule is optimised and how close it is to the reality, allowing us to predict reactions and/or properties more accurately. As one can tell, the NMR which was computationally measured versus the experimentally measured generally showed good agreement. The shifts were generally in the same region of the NMR spectrum and integrations also matched. It would have been better to calculate the NMR with coupling, however due to time constraints this was not possible. A limitation of computational work is also met here. When calculating the NMR computationally, only one conformer in one static position is measured, meaning for a close match to experimental measurements one would have to take many conformational NMR's and average the peaks and integrations. Vibrations and rotations cannot be simulated when calculating NMR data computationally. For example, in the computational data there is a clear peak with integration 3H at 0.96 ppm, this would be one of the methyl groups in the bridgehead. The other methyl is split into 3 different environments in the static model, however in a real situation the bond would rotate rapidly and an average of these 3 environments would be observed giving a singlet with intergration value 3H.

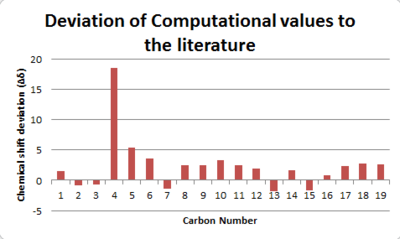

| Spectrum | Carbon number | Computational (δ ppm) | Experimental (δ ppm) [9] |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1 | 212.94 | 211.49 |

| 2 | 147.90 | 148.72 | |

| 3 | 120.13 | 120.90 | |

| 4 | 93.16 | 74.61 | |

| 5 | 65.83 | 60.53 | |

| 6 | 54.92 | 51.30 | |

| 7 | 49.57 | 50.94 | |

| 8 | 48.01 | 45.53 | |

| 9 | 45.69 | 43.28 | |

| 10 | 44.05 | 40.82 | |

| 11 | 41.24 | 38.73 | |

| 12 | 38.63 | 36.78 | |

| 13 | 33.63 | 35.47 | |

| 14 | 32.47 | 30.84 | |

| 15 | 28.31 | 30.00 | |

| 16 | 26.41 | 25.56 | |

| 17 | 24.48 | 22.21 | |

| 18 | 24.07 | 21.39 | |

| 19 | 22.48 | 19.83 |

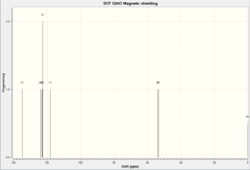

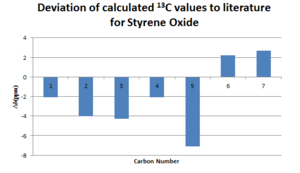

As one can tell, there is a much better agreement with the computational NMR to the experimental NMR. The limitation observed for the 1H NMR is not as pronounced here as the carbon atoms are usually in the same positions with only slightly changes due to vibrations. Rotations along a bond does not affect its environment as significantly as for the hydrogens. In the computational method it is assumed all carbons are of 13C and hence the y-axis is labbelled degeneracy. In experimental NMR, due to the low abundance of 13C it is not possible to calculate the degeneracy, as the intensity of the peaks are also affected by how quick the carbon relaxes from the excited state, i.e spin-spin, spin-lattice relaxation. The longer a carbon is excited, the more intense a peak is. The deviation from literature was also displayed and it is clear to see that the chemical shifts are positively shifted. This maybe be due to an error of the TMS solvent which is electronically incorporated when carrying out the synthetic characterisation. The error would also be caused by the sulphur group which cause spin orbit coupling errors, however this effect is only minor. The carbonyl carbon may also be shifted futher due to the oxygen on the carbonyl, as computationally this effect is not accounted for correctly due to many factors including solvent system, temperature and intramolecular forces. [10]

Free Energies of molecule 17 and 18

| Molecule 18 | |

| Sum of Electronic and thermal free energies | -1651.464193 hartree |

| Free Energy | -4335919.569014 Kj/mol |

| Molecule 17 | |

| Sum of Electronic and thermal free energies | -1651.459442 hartree |

| Free Energy | -4335907.095263 Kj/mol |

As one can tell the free energy of molecule 18 is larger than molecule 17 by 12.47 kj/mol. This energy is large when compared to thermal energy (kbT) and shows that at room temperature there is a large energy barrier between interconversion which supports the definition of atropisomerism and hence each conformer can be isolated.

References

- ↑ G. Grant and W. Richards, Computational Chemistry, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2005DOI:10.1021/ja00398a003

- ↑ H. Rzepa, J. Chem. Edu., 2007, 84, 1535-1540DOI:10.1021/ed084p1535

- ↑ A. Turnbull and H. Hull, Aust. J. Chem., 1968, 21, 1789-1797

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 D. Skala and J. Hanika, Petroleum and Coal, 2003, 45, 105-108

- ↑ J. Vinter and H. Hoffmann, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1974, 96, 5466-5478.DOI:10.1021/ja00824a025

- ↑ J. Schaefer and J. Lark, J. Org. Chem., 1965, 30, 1337-1338.DOI:10.1021/jo01015a564

- ↑ A. McEwen and P. Schleyer,J. Am. Chem. Soc.,1986, 108, 3951-3960.DOI:10.1021/ja00274a016

- ↑ W. Maler and P. Schleyer, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1981, 103, 1891.DOI:10.1021/ja00398a003

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 L. Paquete, N. Pegg, D. Toops, G. Maynard and R. Rogers, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1990, 112, 277-283DOI:10.1021/ja00157a043

- ↑ D. Braddock and H. Rzepa, J. Nap. Prod., 2008, 71, 728-730.DOI:10.1021/np0705918

Analysis of the properties of the synthesised alkene epoxides

Crystallographic Analysis

The Cambridge Crystal Database was searched using the Mercury programe to find the crystal structure of two catalysts used in the asymmetric epoxidation of an alkene, Jacobsen and Shi catalysts. There intramolecular interactions were then analysed.

Shi catalyst

Shi cataylst is a fructose derived molecule which uses protecting groups to form an asymmetric environment which is enantiomerically selective. The above scheme shows the two transition states the catalyst can have, planar and spiro, this is determined by the R groups on the alkene and the steric clashes with the 1,2-dioxane ring and the 1,3-dioxane ring.

C-O bond lengths and the Anomeric effect

The shi catalyst crystal structure was found using single crystal data and is shown below. The two structures shown below are within its unit cell, there differ in the conformation of the 1,3-dioxolane rings, with the cis-1,3-dioxolane being of E4 conformation in both, however they differ in the second dioxolane ring as molecule 1 is of E2 conformation whereas the second molecule is of E4 conformation. These molecules are bonded together through hydrogen bonds and will form the lattice structure.[1]

| Structure | C-O bond | Length(Å) |

|---|---|---|

|

C(1)-O(1) | 1.429 |

| C(2)-O(2) | 1.423 | |

| C(2)-O(6) | 1.415 | |

| C(4)-O(4) | 1.415 | |

| C(5)-O(5) | 1.437 | |

| C(6)-O(6) | 1.434 | |

| C(9)-O(1) | 1.423 | |

| C(9)-O(2) | 1.454 | |

| C(10)-O(4) | 1.456 | |

| C(10)-O(5) | 1.428 | |

| C(13)-O(7) | 1.406 | |

| C(14)-O(8) | 1.405 | |

| C(14)-O(12) | 1.420 | |

| C(16)-O(10) | 1.419 | |

| C(17)-O(11) | 1.428 | |

| C(18)-O(12) | 1.429 | |

| C(21)-O(7) | 1.406 | |

| C(21)-O(8) | 1.460 | |

| C(22)-O(10) | 1.442 | |

| C(22)-O(11) | 1.430 |

Anomeric Effect: When presented with a six membered ring, one would assume the substituents would prefer to sit in the equitorial position as to reduce steric hindrance. Axial position leads to 1,3-diaxial repulsions. However when a heteroatom (in this case oxygen) with a lone pair is substituted for a carbon in the ring the preferred position for substituents becomes axial. This effect which provides stabilisation of the axial position which goes against the inherent steric bias is known as the anomeric effect. The Shi catalyst has a six membered ring with an oxygen heteroatom. One can tell that there is an anomeric center at carbon 2, showing donation from the lone pair of electrons from the carbon on the six membered ring to the σ* orbital of the acetal protecting group. This is anomeric as this group is prefered in the axial position and this interaction can be confirmed by observing the bond lengths. it can be seen that C(2)-O(6) is shorter in length than the C(2)-O(2) bond which is larger by 0.008 Å. For the second molecule the corresponding carbon C(14) is also an anomeric center, in which the substituent sits axially however the change in bond lengths is opposite to that observed in the first molecule. The change in bond length is 0.015 Å in the other opposite way suggesting the oxygen in the substituent is acting as the lone pair donor weakening the C-O bond on the six membered ring. The carbons between the two oxygens in the dioxane rings also show an anomeric interaction. This carbons corresponds to the carbons 9, 10, 20 and 21. It can be seen that one C-O bond length is slightly longer than the other either side of this carbon. This is due to donations from the oxygen into the anti-bonding orbital on each side. The configuration of these dioxane rings explain early account for the magnitude of this interaction.

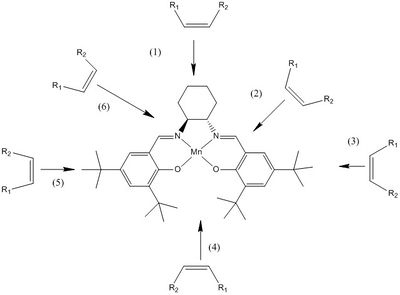

Jacobsens catalyst

Jacobsens catalyst is a Manganese centered salen complex which is enantiomerically selective. Below shows the various trajectories an alkene can have to react with the catalyst to form the epoxide.

Dispersion forces need to be considered for the isotropic H-H interactions between adjacent protons around the jacobsen catalyst. From the Lennard-Jones potential the maximum attractive force between hydrogens is given at a distance of 2.40 Å, this then decreases in attractive force to 2.10 Å. Below 2.10 Å the force of attraction becomes replusive, below is crystallographic analysis of the two crystal structures of the jacobsen catalyst and highlighted are the bonds which are less than 2.40 Å. [2]

|

|

There are two reported crystal structures of the Jacobsens catalyst, labelled TOVNIB01 and TOVNIB02. The key difference lies in the orientation of the methyls in the t-Bu groups which clash together. In TOVNIB01, the methyl ends in the t-bu groups are staggered, whereas the methyl ends in the TOVNIB02 are eclipsed. This staggering allows the t-bu groups to come closer together (208.1pm compared to 232.8pm) pulling the rest of the molecule around and increases the concavity nature of the ligand (157.95 degrees to 154.24 degrees). This increases the steric hinderance from all sides and allowing only one access point. The eclipsed conformer pushes the groups apart and flatterns the plane of the salen ligand.

Epoxide Analysis

NMR Analysis

1,2-Dihydronapthalene oxide DOI:10042/26704

| Spectrum | Calculated peaks | literature peaks[4] |

|---|---|---|

|

7.62 (1H, s) | 7.44 (1H, d, J=7.0 Hz) |

| 7.39 (2H, s) | 7.33-7.21 (2H, m) | |

| 7.25 (1H, s) | 7.13 (1H, d, J= 7 Hz) | |

| 3.56 (1H, s) | 3.89 (1H, d, J= 4 Hz) | |

| 3.48 (1H, s) | 3.77 (1H, t, J= 4 Hz) | |

| 2.95 (1H, s) | 2.83-2.79 (1H, m) | |

| 2.27 (1H, s) | 2.59-2.55 (1H, m) | |

| 2.21 (1H, s) | 2.49-2.41 (1H, m) | |

| 1.87 (1H, s) | 1.80-1.76 (1H, m) |

| Spectrum | Calculated peaks | literature peaks[4] |

|---|---|---|

|

135.4 | 137.1 |

| 130.4 | 132.9 | |

| 126.7 | 129.9 | |

| 123.8 | 128.8 | |

| 123.5 | 126.5 | |

| 121.7 | ||

| 52.8 | 55.5 | |

| 52.1 | 53.2 | |

| 30.2 | 24.8 | |

| 29.1 | 22.2 |

Styrene oxide: DOI:10042/26706

| Spectrum | Calculated peaks | literature peaks[5] |

|---|---|---|

|

7.49 (4H, s) | 7.25 (5H, m) |

| 7.30 (1H, s) | ||

| 3.66 (1H, s) | 3.88 (1H, dd, J=4.0, 2.5 Hz) | |

| 3.11 (1H, s) | 3.16 (1H, dd, J=5.5, 4.0 Hz) | |

| 2.53 (1H, s) | 2,82 (1H, dd, J=5.5, 2.5 Hz) |

| Spectrum | Calculated peaks | literature peaks[5] |

|---|---|---|

|

135.1 | 137.2 |

| 124.1 | 128.1 | |

| 123.4 | 127.7 | |

| 123.0 | 125.1 | |

| 118.3 | ||

| 54.1 | 51.9 | |

| 53.5 | 50.8 |

From the NMR results above it is clear that the computed molecules have a good agreement with the literature and so one can agree that this molecule has been correctly optimised. The deviation from literature as decribed by the 13C-NMR shows minor differences and reasons have been stated earlier. These optimised molecules will then be good to use for the calculation of optical roation

Optical Rotation

Here the optical rotation was calculated by optimising the molecule using the DFT method with the 6-31G(d.p) basis set. Gaussian used calculated the optical rotation at two wavelengths 589 nm and 365 nm. The 589 nm results are shown below, along with literature values. Optical rotation values for the 365 nm wavelength could not be found in the literature.

| molecule | calculated rotation (589 nm) | literature rotation (589 nm) | calculated rotation (365 nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1,2-Dihydronapthalene oxide (R,S) DOI:10042/26711 | +155.82 | +133.00[6] | +522.14 |

| 1,2-Dihydronapthalene oxide (S,R) DOI:10042/26708 | +35.86 | -144.9[7] | +209.45 |

| Styrene oxide (R) DOI:10042/26707 | -30.42 | -24.00[8] | -95.00 |

| Styrene oxide (S) DOI:10042/26709 | +30.14 | +32.1[9] | +94.11 |

The calculated value shows good correlation with the literature however, literature values can be unreliable as there is no standard procedure set when carring out an optical rotation. Many factors affect the rotation value such as temperature, purity of sample, concentration of sample measured and solvent. Therefore in some respects the computational value can be more reliable than finding values in the literature.

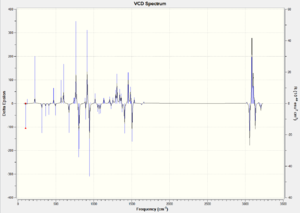

VCD is a method which can be used to measure a molecules optical activity. This sees the response a molecule has to circularly polarised radiation in which the enantiomers should behave like mirror images.

Transition state Analysis, Shi catalyst

| Properties | (RS)1 | (RS)2 | (RS)3 | (RS)4 | (SR)1 | (SR)2 | (SR)3 | (SR)4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calculation Type | FREQ | |||||||

| Basis Set | 6-311G(d,p)) | |||||||

| Gradient | 0.00000174 | 0.00000101 | 0.00000257 | 0.00000148 | 0.00000133 | 0.00000163 | 0.00000181 | 0.00087367 |

| Sum of Electronic and Thermal Free Energies | -1381.120782 | -1381.125886 | -1381.134059 | -1381.126722 | -1381.131343 | -1381.116109 | -1381.126039 | -1381.136239 |

It can be seen than the lowest energy transition state for the shi epoxidation of 1,2-Dihydronapthalene is the (SR)4 which will be analysed futher.

Enantiomeric Excess of 1,2-Dihydronapthalene oxide via Shi Catalyst

To calculate the enantiomeric excess, one must take the lowest of each enantiomer transition state to find out the equilibrium constant. For 1,2-Dihydronapthalene the lowest RS energy is (RS)3 and the lowest energy value for SR is (SR)4:

| Properties | (SR)4 | (RS)3 |

|---|---|---|

| Free Energies (Hartree) | -1381.136239 | -1381.134059 |

| Free Energies (Kj/mol) | -3626173.471722 | -3626167.748131 |

| Change in Free Energy (ΔG) | -572.3591 | |

| k value (SR)4-(RS)3 | 1.257940707 | |

| Enantiomeric Excess | 0.1142371480 | |

| Percentage % (SR)4 | 11.4 lit: 32 (SR)[10] | |

It can be seen that the literature value for the enantiomeric excess confirmes the computational result in the respect that its the (SR) enantiomer. However, the values are quite different. This is due to many factors that contribute to the selectivity of a reaction such as, solvent, temperature, pH, oxidant etc. These factors are not accounted for computationally and it is also hard to compared the value to literature as the conditions of reaction change from paper to paper.

Transition State Analysis Jacobsen epoxidation

| Properties | (R)1 | (R)2 | (S)1 | (S)2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calculation Type | FREQ | |||

| Basis Set | 6-311G(d,p)) | |||

| Gradient | 0.00000340 | 0.000005761 | 0.00000298 | 0.00000158 |

| Sum of Electronic and Thermal Free Energies | -3343.960889 | -3343.962162 | -3343.969197 | -3343.963191 |

It is be seen that the lowest transition state for the jacobsen epoxidation of styrene is the (S)1 transition and hence this transition state will be analysed further.

Enantiometric Excess of Styrene Oxide via Jacobsen catalyst

| Properties | (S)1 | (R)2 |

|---|---|---|

| Free Energies (Hartree) | -3343.969197 | -3343.962162 |

| Free Energies (Kj/mol) | -8779591.795517 | -8779573.325123 |

| Change in Free Energy (R)2-(S)1 (ΔG, J/k/mol) | -18470.394 | |

| k value | 1644.740638 | |

| Enantiomeric Excess | 0.9987847417 | |

| Percentage % (S) | 99.88 lit: 19 [11] | |

The difference between the literature and the computational is very significant. It suggests that the s enantiomer is in excess but not by much. When looking at the transition state below it can be seen that the catalyst is not complete. It is missing the t-Bu groups on the ends of the salen ligand. This changes the stereochemical control quite significantly. The transition state analysed suggest the trajectory is number (6) as shown in section 8.1.2. This is described further below and explains why this is the lowest energy pathway. However when including the t-Bu groups onto the salen ligand, the approach described by computation will raise in energy as this becomes a lot more sterically hindered. The new trajectory will be in approach (2), as suggested by Kasuki, in which the phenyl group will be repelled by the benzene ring in the salen ligand, this keeps the enantiomer which will be in excess the same as the computed value but to a much lower degree, corresponding to literature. The t-Bu group will hinder the phenyl group so it will approach at an angle and not flat, which is shown in the previous transition state, and hence the enantiomeric excess will be reduced. The fact that the molecule is not the complete jacobsens catalyst makes it unreliable to compared to the literature.

NCI Analysis

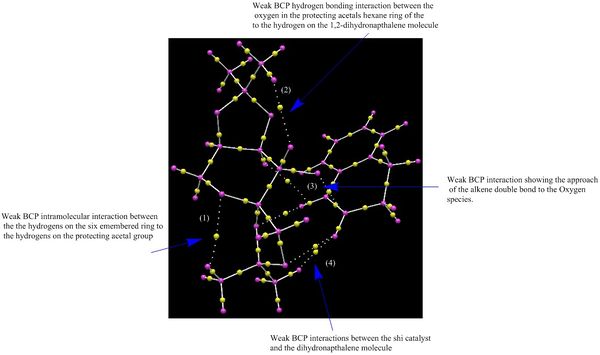

| NCI Analysis of the transition state to the epoxidation of 1,2-Dihydronapthalene via shi catalyst | |

|

|

Above is the lowest transition state for the shi epoxidation of dihydronapthalene. Transistion state theory states the path with the lowest energy transition state will proceed. By looking at this transition state one can tell that the most favoured enantiomer will be the (S,R)-Dihydronapthalene, which is complimented by literature.

| NCI Analysis of the transition state to the epoxdidation of styrene via the jacobsens catalyst | |

|

|

Further study

The literature was searched to find an epoxide with an optical rotation above +500° or -500°. Pulegone was found to have an optical rotation which met this requirement and is stated above. The literature has used hydrogen peroxide to carry out an epoxidation of the alkene. It would be interesting to observed the effects of the carbonyl on the selectivity using the jacobsen and shi catalyst. One would predict the molecule to approach in trajectory 2 of the jacobsens catalyst which is shown in section 8.1.2 This has the minimum steric interaction from all other possible trajectories.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 M.Durik, V.Langer, D.Gyepesova, J.Micova, B.Steiner and M.Koos, Acta Cryst., 2001, 57, 672.DOI:10.1107/S160053680101073X

- ↑ D. Barton, Sci. Vol., 1970, 169, 539-544.DOI:10.1126/science.169.3945.539

- ↑ J. Yoon, T. Yoon, S. Lee and W. Shin, Acta Crystallogr., 1999, 55, 1766.DOI:10.1107/S0108270199009397

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 M. Robinson, A. Davies, R. Buckle, I. Mabbett, S. Taylor and A. Graham, Org. Biomole. Chem., 2009, 7, 2559-2564 DOI:10.1039/B900719A

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 H. Hachiya, Y. Kon, T. Matsumoto, Y. Ono, K. Sato, Synthesis, 2011 , 7, 1092 - 1098 DOI:10.1055/s-0030-1258467

- ↑ D. Boyd, N. Sharma, R. Agarwal, N. Kerley, R. Austin, S. McMordie, A. Smith, H. Dalton, A. Blacker and G. Sheldrake, J. Chem. Soc., 1994, 14, 1693-1694 DOI:10.1039/c39940001693.

- ↑ H. Sasaki, R. Irie, T. Hamada, K. Suzuki and T. Katsuki, Tetrahedron, 1994, 50, 11827-11838DOI:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)89298-X

- ↑ S. Bettigeri, D. Forbes, S. Patrawala, S. Pischek and M. Standen, Tetrahedron, 2009 , 65, 70-76DOI:10.1016/j.tet.2008.10.019

- ↑ H. Lin, Y. Liu, J. Qiao, Z. Wu, Journal of Molecular Catalysis B: Enzymatic, 2010 , 67, 236-241DOI:10.1016/j.molcatb.2010.08.012

- ↑ Z. Wang, Y. Tu, M. Frohn, J. Zhang, and Y. Shi, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1997, 119, 11224-11235 DOI:10.1021/ja972272g.

- ↑ G. Morris, S. Nguyen, J. Hupp J. Mol. Cat: A, 2001, 174, 15-20 DOI:10.1016/S1381-1169(01)00165-0

- ↑ W. Reusch , C. Johnson, J. Org. Chem., 1963, 28, 2557-2560 DOI:10.1021/jo01045a016.

- ↑ R. Hill, C. Abacherli and S. Hagishita,Can. J. Chem., 1994, 72, 110-113 DOI:10.1139/v94-017#.UqG5tPT6GSp.