Rep:Mod:OGD13

The Cope Rearrangement [1] and the Dies-Alder Cycloaddition[2] are two examples of fully concerted, pericyclic reactions that have found a high level of use within synthetic chemistry. This is due to them presenting a relatively easy, stereospecific and regioselective route to the formation of carbon-carbon bonds - in particular in the case of Dies-Alder where a new six-membered ring is formed.

Computational theory can be applied to these reactions to study various features, including reactant conformational energies as well as the nature of the transition states. This can be used to help understand the reaction selectivity, as well as to aid in the creation of future, similar reactions.

Computational Theory

Throughout computational chemistry, there are multiple different levels of theory that can be used to perform calculations. Each of these involves different approximations and assumptions and so different equations are used - this results in theory methods varying in factors such as accuracy and speed. As such they have various advantages and disadvantages, so different ones are chosen based on the situation.

Hartee-Fock

The Hartee-Fock method (HF)[3] is one such method of approximation and is used to solve the time-independent Schrödinger equation. It makes use of a large number of approximations, including the Born-Oppenheimer approximation - that the motion of nuclei and electrons can be seperated - and the mean-field approximation, which transforms multi-body problems into one-body ones using an average interaction instead of many inter-body ones. It also involves other simplifications, such as saying that a single Slater determinant is enough to describe each energy eigenfunction. As such it is less accurate than others methods, but is quick for small systems.

Density Functional Theory

The Density Functional Theory (DFT)[4] is used to investigate the electronic structure of many-bodied systems and uses functionals (functions of functions) to model the properties. It chiefly involves two principles; that the ground state is determined by an electron density based on only 3 spatial coordinates and that the ground state electron density minimises overall energy. It still features some simplifications, again one being the Born-Oppenheimer approximation but also the local-density approximation - that the properties at a point depends only on the electron density at that same point. In this case however, the results are far closer to experimental ones than for HF, although run time is often long for complex systems.

BY3LP

BY3LP (Becke, three-parameter, Lee-Yang-Parr)[5] is an example of an exchange-correlation functional and is a commonly run form of the DFT in computational chemistry.

QST2

QST2[6] is a method that is used to find transition state geometries. It involves the setting up of both reactant and product structures and so is often time-consuming to start, but has the advantage over other methods for finding TS's in that it doesn't require prior knowledge of what the TS looks like. As such it is good in the cases where the TS is either unknown, or if it is very complex and fiddly to recreate with good accuracy.

Austin Model 1

The Austin Model 1 (AM1)[7] is a semi-empirical method, this being one based on the HF method but involving additional approximations as well as parameters based on empirical data, making it useful for highly complex systems where the HF grows too expensive. Specifically, the AM1 method is based off of the Neglect of Differential Diatomic Overlap integral approximation[8] - that the overlap matrix can be replaced by a unit matrix.

Notes on basis sets

A basis set basically governs what orbitals are involved in a calculation. This can include a large amount of detail about the orbitals, including their varying sizes and shapes. The double-zeta basis set allows for the treatment of orbitals separately to allow for their differing properties, by producing an equation with two additive components (two Slater-type orbitals) that vary by a factor of zeta (allowing for the diffuseness of the orbital) and by proportion (i.e. the second term can be anything from 0 to the value of the first component multiplied by zeta.)[9]

As it can be a long process calculating this double-zeta for every orbital, often it is only calculated for the valence orbital, with the inner-shell electrons treated more simply as they contribute less to overall properties. This is known as a split-valence basis set and it is this that is used during a lot of computational work. Examples used in this project are 3-21G and 6-31G*. To break down the meaning of the numbers, for 3-21G:

- 3 - The number of functions that are summed to produce an orbital for the inner-shell electrons.

- 2 - The number of functions that are summed to produce the first component of the double-zeta.

- 1 - The number of functions that are summed to produce the second component of the double-zeta.

In short, the higher the numbers, the more complex the basis set and so the more accurate, but slower, the technique.

One other detail of the basis set is polarisation, brought about by orbitals of different atoms being close together. The presence of an asterix, such as in 6-31G*, shows that this has been accounted for in the p orbitals, increasing accuracy further.

Nf710 (talk) 17:35, 24 February 2016 (UTC) this is an excellent brief overview of the methods. you have clearly explain each one used well done.

Cope Rearrangement

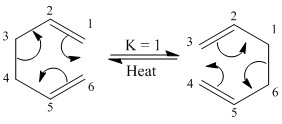

The Cope-Rearrangement[10] is an example of a pericyclic reaction and is the [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement of 1,5-dienes. By definition, a sigmatropic rearrangement involves no overall change in the number of sigma bonds – varying it from the other forms of pericyclic reactions (electrocyclic reactions and cycloadditions.) It is a fully concerted rearrangement, passing through a single, cyclic transition state.

In the case of the Cope-Rearrangement, the bonds broken and formed are both carbon-carbon bonds, making the rearrangement often fairly thermoneutral, aside from in examples such as the Oxyanionic-Cope, where the presence of an oxygen atom bound to the 3-position shifts the equilibrium by means of forming a stronger carbon-oxygen double bond [11]. Generally, an increase in the complexity of the molecule shifts the reaction away from thermoneutrality. Heating is required however to shift between the structures to overcome the energy barrier of coiling the molecule into a geometry suitable for forming the transition state.

Computational chemistry can be used to establish several facts. Firstly, the most stable reactant geometry can be determined and following this, the most stable transition state structure.

Nf710 (talk) 17:51, 24 February 2016 (UTC) Excellent understanding of the mechanisms and excellent reference.

Reactant Conformation and Optimisation

The first information that can be gained from computational chemistry for the Cope-Rearrangement is to examine the energies of various reactant structures. Without it, it might be expected that the lowest energy conformation of 1,5-hexadiene would be the one that places the two arms (carbons 1 and 2 and carbons 5 and 6) as far apart as possible.

Considering the C3-C4 dihedral angle, in terms of decreasing energies:

- 0°: Highest energy case - Arms are extremely close together so steric clashing is high.

- 120/-120°: Arms are now far apart but close to a hydrogen from the opposite carbon.

- 60/-60°: Although the arms are fairly close, there are no direct steric clashes like at 0 or 120°.

- 180°: Lowest energy case - Antiperiplanar arrangement means the arms are as far apart as can be.

Rotation is also possible around the C2-C3 and C4-C5 bonds however and again it is expected that the lowest energy conformation would be the one that overall places carbon 6 furthest away from carbon 1. This can be tested using computational chemistry.

The theory method used first is HF/321G due to its speed of completion. Using this, the energy of various conformations can be examined:

Nf710 (talk) 18:12, 24 February 2016 (UTC) You havent really followed the format of the lab script. however it seems you have done the work

| Conformation | C3-C4 Dihedral Angle | Structure | Point Group | Energy (Hartees) | Relative Energy (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 60° (Gauche) | Structure | C1 | -231.69266 | 0 |

| 2 | 60° (Gauche) | Structure | C2 | -231.69153 | 0.71 |

| 3 | 180° (APP) | Structure | C2 | -231.69260 | 0.04 |

| 4 | 180° (APP) | Structure | Ci | -231.69254 | 0.08 |

It is in fact the case that conformation 1, which is gauche, is the overall lowest in energy. This is very different to what might be expected from sterics alone, which would predict that a structure similar to conformation 4 (APP and with C2-C1 at 180° to C5-C6.) The reason for this is electronic. In this gauche form, donation between the pi systems is possible, overall stabilising the conformation, as shown in the HOMO.

Another level of optimisation can then be performed - BY3LP/631G*. It is usually beneficial to perform first the simpler theory, then the more complex one on top of the result as this often is far quicker than starting with BY3LP/631G*. This will be done on Conformations 1 and 4. For 4, the geometry produced is very similar to that under the HF/321G theory. Bond angles change marginally (but never by more than around 1°), as do bond lengths, with double bonds lengthening and single bonds shortening. The C3-C4 dihedral angle remains at 180°.

Nf710 (talk) 18:14, 24 February 2016 (UTC) This is not a proper geometry conparision. However excellent uses of the orbitals from the .chk file to explain the ordering.

Interestingly, performing the BYL3P/621G* theory on Conformation 1, previously the lowest energy, produces one that is actually higher than the corresponding BYL3P/631G* Ci (4) molecule.

Bond vibrations can be examined by performing frequency analysis. This can confirm that all vibrations are positive and therefore real, hence displaying it is the minimum. It is indeed the case for both Conformations 1 and 4 that there are no imaginary frequencies and so both are optimised to a minimum energy for that conformation. An imaginary (negative) frequency relates to a negative gradient on the potential energy surface. At a minimum, each vibration produces a less stable molecule and so a positive energy increase, hence also a positive frequency (by the Planck-Einstein relation.) At a non-minimum energy, there can be a negative local gradient on the potential energy surface and hence the vibration that corresponds to this has a negative frequency.

The frequency analysis also provides information about quantities comparable to experimental work. These are:

- The sum of electronic and zero-point energies (0K)

- The sum of electronic and thermal energies (298.15K and 1 atm pressure)

- The sum of electronic and thermal enthalpies (298.15K and 1 atm pressure)

- The sum of electronic and thermal free energies (298.15K and 1 atm pressure)

For Conformations 1 and 4 at BY3LP/631G* in terms of Hartees:

| Conformation | Electronic + ZP Energy (OK) | Electronic + Thermal Energy (298.15K) | Electronic + Thermal Enthalpy (298.15K) | Electronic + Thermal Entropy (298.15K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | -234.468719 | -234.461477 | -234.460533 | -234.500173 |

| 4 | -234.469219 | -234.461869 | -234.460925 | -234.500809 |

Or in terms of relative kcal/mol:

| Conformation | Electronic + ZP Energy (OK) | Electronic + Thermal Energy (298.15K) | Electronic + Thermal Enthalpy (298.15K) | Electronic + Thermal Entropy (298.15K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | +0.313755 | +0.24598392 | +0.24598392 | +0.39909636 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

This shows that the Conformer 4 is now definitely lower in energy than the Conformer 1 at the higher level of theory of BY3LP/631G*. This is a more complex, more accurate calculation than HF, displaying that it is likely Conformer 4 that is the most stable ground state and so in activation energy calculations, it is this that is used.

Nf710 (talk) 18:15, 24 February 2016 (UTC) Nice comparison of thermochemistries

Optimizing the Transition Structures

For the Cope-Rearrangement, there are two main possible conformations of the cyclic, six-membered transition state - a chair or a boat. It is the chair that is generally more stable, this being down to unfavourable through-space secondary orbital interactions in the boat[12] - this stability can be shown using computational techniques.

Chair

Firstly considering the chair structure, optimisation can be performed in one of two ways. Both involve manually producing a structure similar to the chair first from two allyl fragments. When optimising to a TS, the starting structure must be fairly close already or the negative curvature of the energy curve is not found.[13] The methods of optimisation after this are:

- Producing a force constant (Hessian) matrix that is updated throughout a standard HF/321G optimisation (but with "Optimisation to a TS (Berny)" instead of "Optimisation to a Minimum" selected.)

- Freezing the reaction coordinate (i.e. between the terminal carbons of each allyl fragment) and minimising the energy of the rest of the structure (as non-reacting parts should be in their relaxed state.) The coordinate can then be unfrozen and an optimisation to a TS ran (like in the first method.)

The advantage of the latter is that is less important for the starting structure to resemble the TS as it is optimised in two steps, the first of which makes it more closely resemble to chair. Secondly, the whole Hessian doesn't have to be produced (which can be expensive and time-consuming) as just considering the reaction coordinate can produce a good estimate for this.

So first considering the force matrix method, a structure that looks chair-like is produced. To confirm that this is a TS for the Cope-Rearrangement, frequencies can be observed from the final structure. This time, there should be a single negative frequency as the TS in a local energy maxima so therefore the gradient of the potential energy curve is negative around it. There shouldn't be more than one as this would suggest the transition state can relax into multiple different products. As there is only one, at -817.87 cm-1, and the animation (shown) reflects that it is the correct one, with C3-C4 lengthening whilst C1-C6 shortens, it is safe to say the correct chair TS has been produced.

Similarly, the final result from the freezing reaction coordinate method is a chair structure with a negative frequency reflecting the Cope-Rearrangement at around -817 cm-1.

Boat

A different optimisation method can be used for the boat transition state - QST2. For this, both the reactant and the product are used in the calculation and the transition state between them is found. Like for the chair, the reactant conformation used was 4 (APP, Ci) as this is the lowest energy under BY3LP/631G* (the chair and boat structures will later be optimised under this for activation energy calculations.) The difference in calculation method for this is that now instead of "Optimisation to a TS (Berny)", "Optimisation to a TS (QTS2)" was performed.

Using Conformation 4 directly, and creating the product in the same APP arrangement but with the atoms exchanged to reflect the Cope-Rearrangement, fails to accurately produce a boat structure. It instead results in a chair, which isn't unexpected considering the reactant is very dissimilar to a boat - requiring extreme rotations around central bonds that the calculation doesn't perform. The starting angles therefore can be changed to produce a more boat like structure (C3-C4 dihedral angle of 0°, C2-C3-C4 and C3-C4-C5 bond angles of 100°) and the same calculation being run this time does result in a boat. Checking frequencies again to confirm, there is now one negative frequency at -840.22 cm-1 that when animated represents the Cope-Rearrangement.

Nf710 (talk) 10:36, 25 February 2016 (UTC) Correct frequeicies but your analysis of the frozen coordinate chair is somewhat lacking.

Transition State Analysis

From simply observing these transition state structures, it is impossible to say for certain which conformer of 1,5-hexadiene they connect to. For this, computational chemistry has the Internal Reaction Coordinate (IRC) method [14]. This will be done on the chair transition structure.

The IRC method finds the minimum potential energy pathway between two structures, in this case from the transition state down to the local minimum (i.e. the reactant conformer.) This only needs to be computed in one direction due to the symmetrical nature of the reaction coordinate and the force matrix is continuously computed throughout. The number of points on the pathway can be changed, but in this case 60 suffices. The molecule produced is clearly gauche and corresponds to a conformation not previously calculated - it has an energy of -231.69167 Hartees and so is around 0.62 kcal/mol higher than Conformer 1 (at HF/321G.) It is therefore not actually the lowest energy possible conformation of 1,5-hexadiene, but is the local minimum that led to the chair TS. The structure is shown here

Nf710 (talk) 10:56, 25 February 2016 (UTC) Where is the graph? you could have compared that energy to the ones in the appendix to see what conformer that you got.

After optimisation to the B3LYP/631G* level of theory, the chair and boat structures can be compared at both levels of theory. Here it is seen that the geometries remain fairly similar, as is expected as this is the case for the reactant optimisations done previously, but the energy difference between the chair and boat changes.

| Energy (Hartees) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Conformation | HF/321G | BY3LP/631G* |

| Chair | -231.61932 | -234.55693 |

| Boat | -231.60280 | -234.54308 |

| Difference | 0.01652 | 0.01385 |

At the higher level of theory, the difference between the chair and boat decreases, but by a fairly low amount so there isn't too much of a discrepancy between the methods (unlike for finding the lowest energy reactant conformation.)

An important piece of information that can then be compared to experimental values is activation energies. At BY3LP/631G* and using the lowest energy Conformation 4 as the reactant energy, the activation energy at 0K in Hartees and kcal/mol can be calculated:

| Structure | Energy (Hartees) | Acivation Energy (Hartees) | Activation Energy (kcal/mol) | Experimental Result (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reactant | -234.61171 | - | - | - |

| Chair | -234.55693 | 0.05478 | 34.375 | 33.5 ±0.5[15] |

| Boat | -234.54308 | 0.06863 | 43.06601 | 44.7 ±2.0 |

As such, the results from the computational work is similar to that from experiments, for the boat it is within the range given, whilst it is only slightly out for the chair.

Nf710 (talk) 11:05, 25 February 2016 (UTC) This is an inadequate analysis. your energies are also incorrect and you havent displayed the energies to enough dps. this could be the reason for your errors but i am not sure. In general you have a really good understanding of the theory which is excellent but your analysis of the work is abit lacking.

Dies-Alder Cycloaddition

The Dies-Alder cycloaddition[16] is another form of pericyclic reaction and so is once again fully concerted, proceeding via a single, cyclic transition state and thus is stereospecific based on reactant geometries. It is a [4+2] cycloaddition, displaying that it involves a 4 electron component, an s-cis conjugated diene, and a 2 electron component, the dieneophile. This orbital interaction is from the HOMO and LUMO of each component.

For successful reaction, the dieneophile usually must carry an electron-withdrawing group (EWG.) This pushes down the HOMO and LUMO energies to ones more similar to the diene, creating a stronger interaction that allows for reaction. The exception to this need for an EWG is in intramolecular Dies-Alder reactions, where there is no entropic penalty to ring formation and so the stability of a six-membered ring prevails.

Like all pericyclic reactions, the Woodworth-Hoffmann rules can be applied to the Dies-Alder (diagram) to show that it is a fully thermally allowed reaction.

A key element of the Dies-Alder reaction is whether the thermodynamic product (known as exo) or the kinetic product (endo) is formed. In the case of a non-substituted dieneophile, these are identical but when there is a substituent this can face either towards or away from the diene during reaction, creating one of these two products. As the dieneophile will often carry an EWG, which likely possesses pi-orbitals, if this is facing towards the diene, secondary orbitals interactions stabilise the transition state and result in formation of the endo product (lowered energy barrier, hence kinetic product.) The exo product is the more thermodynamically stable due to decreased steric clashes.

Computational chemistry can be used to analyse multiple areas of the Dies-Alder reaction. Firstly, the HOMO and LUMO of both components of the most basic iteration (cis-butadiene and ethylene) can be visualised to determine what it is that combines. Then the exo and endo transition states of a more complex reaction can be computed to analyse endo stabilisation by secondary orbital interactions.

Orbital Interactions

To display how the orbitals interact during a regular Dies-Alder reaction, the basic example of cis-butadiene and ethylene can be used. It should be noted that this reaction is unlikely to occur as there will be a large HOMO/LUMO energy mismatch between the two without the presence of an EWG on the diene (diene orbitals too high in energy without it.)

(The EWG should be on the dieneophile for normal demand Tam10 (talk) 10:57, 24 February 2016 (UTC))

Looking first at cis butadiene, and optimising to a minimum under AM1 (a semi-empirical method that will be used throughout this section), the HOMO and LUMO can be observed. It is plain that the HOMO is antisymmetric with respect to the plane of symmetry (the mirror plane down the centre of the molecule), whilst the LUMO is symmetric. Then considering the ethylene, in this case the order is reversed - a symmetric HOMO and asymmetric LUMO - and hence it the HOMO of one that reacts with the LUMO of the other, and vise versa, to generate one symmetrical and one asymmetrical orbital.

(I know it seems obvious which is which, but you should say which orbitals interact to form the HOMO and LUMO specifically Tam10 (talk) 10:57, 24 February 2016 (UTC))

As the reaction is between π and π* orbitals, it is expected that the geometry in the transition state is one that maximises the overlap of these orbitals. As such the ethylene sits below (or above, in this case they are identical) and at an angle away from the cis-butadiene (as shown in the animation.) The first step to visualising this TS is to produce the two components and optimise them under AM1 (this was previously performed to observe the orbitals), before creating an approximate TS structure using these. The force matrix method, as used in the Cope-Rearrangement to produce a chair, can then be performed to optimise to TS. Once again the check for success is a single imaginary frequency that corresponds to the Dies-Alder reaction. This means a shortening on the central cis-butadiene bond (single to double) and an extension of the outer two bonds (double to single), as well as the ethylene bond shortening also. This is the case and was found at -955.73 cm-1. The new sigma bonds that are forming have a distance of 2.11988 Å and 2.11897 Å.

Observing the animation closely, it can be seen that the bonds form synchronously. This is in contrast to the first positive frequency found at 147.32 cm-1, where there is an asynchronous pattern to the atoms moving together (so one pair of atoms that will form a bond move together, then the other pair as the first move apart.)

(No bond forming behaviour in the lowest positive frequency. The C-C distances aren't changing during this vibration Tam10 (talk) 10:57, 24 February 2016 (UTC))

The HOMO of the transition state can then be observed. It is clear that this has a nodal plane that lies down the centre of components (the σv mirror plane) and is antisymmetric. The LUMO on the other hand is symmetric. Combining two symmetric orbitals should also produce a symmetric one so the TS HOMO is clearly formed from the LUMO of cis-butadiene and the HOMO of ethylene, whilst the LUMO is from the opposite.

Considering a typical single carbon carbon bond is 1.54 Å[17], the newly forming sigma bonds at over 2 Å are clearly significantly longer than this (as expected as the transition state only has these bonds partially formed.) They are however within the Van der Waal's radius of two carbon atoms, this totaling 3.4 Å. The existing carbon-carbon bonds all lie below 1.54 Å, but above the 1.33 Å expected of a double bond. The ethylene bond is now 1.38290 Å, the external cis-butadiene's are 1.38187 Å and the internal 1.39749 Å (slightly longer as this was originally a single bond.) All of these therefore have a bond order between 1 and 2, as expected when converting between single and double bonds.

(Interesting analysis in the last two paragraphs. The energy difference from secondary orbital overlap is probably very slight, but it would come from the HOMO as you suggest. There is also steric hindrance from the hydrogens on the exo Tam10 (talk) 10:57, 24 February 2016 (UTC))

Exo vs Endo Product

As discussed previously, a principle regioselectivity issue in the Dies-Alder is the direction a substituent on the dieneophile faces in the transition state, resulting in an exo (away from diene) or endo (towards diene) product. The endo product represents the kinetic path of reaction, as secondary orbital effects stabilise the transition state. Computational chemistry can display this well.

For this, the reaction between 1,3-cyclohexadiene and maleic anhydride will be studied. This is a well known and studied reaction. Both transition states are first computed in AM1 (via HF/321G and BY3LP/631G*) and then analysed. Considering energies:

| Structure | Energy (Hartees) | Energy (kcal/mol) | Relative Energy (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endo | -0.051505 | -32.320 | 0 |

| Exo | -0.050420 | -31.639 | +0.681 |

Thus as expected, the endo transition state is lower in energy than exo and so it is the endo product that is the kinetic result of the reaction. To test if the exo is actually the thermodynamic product in this case, the products geometries could be optimised and their energies taken - exactly as done with the reactants earlier.

Another thing to observe in the transition state are the bond lengths, of both the existing internal bonds and the newly forming ones (all in Å.)

| Structure | C1-C2/C3-C4 | C2-C3 | C5-C6 | C1-C5/C4-C6 (Newly forming bonds) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endo | 1.39307 | 1.39723 | 1.40850 | 2.16224 |

| Exo | 1.39438 | 1.39676 | 1.41011 | 2.17044 |

There is clearly little difference between the exo and endo states, with the newly forming bonds having a bond order well below 1, and all the existing ones between 1 and 2 (as all are converting between single and double.) It should be noted however that the newly forming bonds in the endo product are shorter than in exo.

One other difference in the geometry is in the variation between the (C=O)-O-(C=O)- of the maleic anhydride and the CH2-CH2/CH2=CH2 that is near to it on the cyclohexa-1,3-diene, shown by arrows in the transition state diagram. In the endo case, so between the carbonyl carbon and the closest carbon of the CH2=CH2, this distance is 2.89195 Å, whilst for exo (closest carbon of CH2-CH2) it is the longer 2.94520 Å. Although not a huge variation, this does show a slight geometry difference, especially when combined with the fact that the newly forming bonds are shorter in the endo state. This shows the reactants are clearly closer together in endo, suggesting evidence for secondary orbital interactions pulling them together and stabilising.

To try and further establish this fact, the HOMO of both states can be visualised. Looking at these, there is no obvious significant difference that displays the secondary orbital effects expected between the carbonyl and alkene π systems. There are however subtle indications in the shape of the π orbital between the carbonyl and the alkene in the endo state, compared to simply above the alkene in the exo. In the endo, the orbital is slightly convex, curving out towards the carbonyl group, in comparison to in exo, where the same stretch of orbital is concave. This displays that the orbital is interacting slightly with the carbonyl π system, but this is very much a small, secondary effect.

Conclusions

Computational chemistry is extremely useful for modelling many aspects of a reaction and has been shown to provide results similar to those from experiments, so long as the appropriate theory is used. There are many different possible levels of theory - each of these has different advantages and reasons to be used.

For the Cope-Rearrangement, it was shown that depending on the calculation theory, different conformers of reactants are the most stable. At HF/321G, a gauche conformer (1) was shown to be the lowest due to the availability of pi donation between the pi systems, whilst at BY3LP/631G* it was the antiperiplanar conformer 4. The chair and boat transition states were then observed and the chair was shown to be the lower energy of the two. Activation energies computed for these were shown to match experimental results fairly well.

For the Dies-Alder Cycloaddition, s-cis-butadiene and ethylene were optimised and their HOMO and LUMO energy levels observed to identify which were symmetrical (LUMO of butadiene, HOMO of ethylene) and which asymmetrical (HOMO of butadiene, LUMO of ethylene) to identify the combinations. The transition state for this reaction was produced and again the orbitals analysed to display their symmetry and show what combination produces the HOMO (asymmetric) and the LUMO (symmetric.) Finally, for the more complex maleic anhydride and 1,3-cyclohexadiene, the transition states corresponding to the endo and exo products were optimised and their energies calculated. It was shown that the endo is slightly more stable, proving this represents the pathway to the kinetic product and evidence of the secondary orbital interactions that cause this stabilisation was seen in the HOMO and in the molecular geometry.

It should be borne in mind that in the calculation of these Dies-Alder transition states, some effects have not been factored in. For example, solvent effects could stabilise or destabilise one TS over the other. Additionally there were many assumptions made during the calculations (such as the Born-Oppenheimer approximation) that do result in some inaccuracy in the results.

References

- ↑ Arthur C. Cope; et al.; J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1940, 62, 441.

- ↑ Kloetzel, M. C. (1948). "The Diels-Alder Reaction with Maleic Anhydride, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California". Org. React. 4: 1–59. doi:10.1002/0471264180.or004.01. ISBN 0471264180.

- ↑ R. McWeeny, B.T. Sutcliffe, Fundamentals of Self-Consistent-Field (SCF), Hartree-Fock (HF), Multi-Configuration (MC)SCF and Configuration Interaction (CI) schemes, Computer Physics Reports, Volume 2, Issue 5, Pages 219–278, April 1985, doi:10.1016/0167-7977(85)90009-7

- ↑ Gross, Eberhard KU, and Reiner M. Dreizler, eds. Density functional theory. Vol. 337. Springer Science & Business Media, 2013.

- ↑ K. Kim and K. D. Jordan (1994). "Comparison of Density Functional and MP2 Calculations on the Water Monomer and Dimer". J. Phys. Chem. 98 (40): 10089–10094. doi:10.1021/j100091a024

- ↑ Chunyang Peng, H. Bernhard Schlegel, Combining Synchronous Transit and Quasi-Newton Methods to Find Transition States, Israel Journal of Chemistry, Volume 33, Issue 4, pages 449–454, 1993

- ↑ Dewar, Michael J. S.; Zoebisch, Eve G.; Healy, Eamonn F.; Stewart, James J. P., "Development and use of quantum mechanical molecular models. 76. AM1: A new general purpose quantum mechanical molecular model". Journal of the American Chemical Society 107 (13): 3902., 1985 doi:10.1021/ja00299a024

- ↑ J. Pople and D. Beveridge, Approximate Molecular Orbital Theory, McGraw-Hill, 1970

- ↑ https://www.shodor.org/chemviz/basis/teachers/background.html - Accessed on 11/02/2016

- ↑ Rhoads, S. J.; Raulins, R. Org. React., 1975, 22, 1

- ↑ A Synthesis of Ketones by the Thermal Isomerization of 3-Hydroxy-1,5-hexadienes. The Oxy-Cope Rearrangement Jerome A. Berson, Maitland Jones, , Jr. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964; 86(22); 5019–5020. doi:10.1021/ja01076a067

- ↑ K. J. Shea, G. J. Stoddard, W. P. England, C. D. Haffner, Origin of the Preference for the Chair Conformation in the Cope Rearrangement. Effect of Phenyl Substituents on the Chair and Boat Transition States, Department of Chemistry, University of California, Irvine, Irvine, California 92717, 1991

- ↑ Chunyang Peng, Philippe Y. Ayala, H. Bernhard Schlegel, Michael J. Frisch, Using redundant internal coordinates to optimize equilibrium geometries and transition states, Journal of Computational Chemistry, Volume 17, Issue 1, Pages 49–56, 15 January 1996, DOI: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-987X(19960115)17:1<49::AID-JCC5>3.0.CO;2-0

- ↑ http://www.cup.uni-muenchen.de/ch/compchem/geom/irc1.html Accessed on 11/02/2016

- ↑ Roald Hoffmann, Wolf-Dieter Stohrer, The Cope Rearrangement Revisited, Department of Chemistry, Cornel1 University, Ithaca, New York 14850, 1971

- ↑ Kamyar Afarinkia , Michael J. Bearpark ,Alexis Ndibwami, Computational and Experimental Investigation of the Diels−Alder Cycloadditions of 4-Chloro-2(H)-pyran-2-one, J. Org. Chem., 2003, 68 (19), pp 7158–7166 DOI: 10.1021/jo0348827

- ↑ Frank H. Allen, Olga Kennard, David G. Watson, Lee Brammer, A. Guy Orpen, Robin Taylor, Tables of bond lengths determined by X-ray and neutron diffraction. Part 1. Bond lengths in organic compounds, J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2, 1987, S1-S19, DOI: 10.1039/P298700000S1