Rep:Mod:NightAngel

Module 1

Owen Davis

Introduction and Aims

Computational techniques are now widely used to model various aspects of the structure, and even the reactivity, of various organic molecules. This type of modelling allows one to not only rationalise the results of a reaction, but also to predict various new reactions which might not be considered otherwise. Module 1 of this computational lab course focuses on illustrating the diversity of this powerful technique of molecular modelling, which allows various molecular properties to be predicted through the optimisation of the molecular geometry to an energy minimum and analysing the various contributions to the total energy.

In effect, this modelling technique is interpolative and relies on well characterised data and known molecules. This therefore means that it becomes less accurate when knowledge of electron density in a molecule is needed, as well as when the molecules have not been reported (See Mini Project Introduction).

Modelling using Molecular Mechanics

The Hydrogenation of Cyclopentadiene Dimer

Dimerisation of Cyclopentadiene

It was shown by Wilson et al[1] that cyclopentadiene readily undergoes dimerisation at room temperature. This occurs via a Diels-Alder [π4s+π2s] cycloaddition reaction. This reaction could theoretically form two products; the exo (1) and endo (2) products. The reaction scheme is shown in Figure 1:

The relative stabilities of the two products can be determined by modelling the products and then optimising their geometries using the MM2 program. Analysis using the MM2 program on ChemBio3D shows that the formation of the endo dimer (2) is thermodyamically disfavoured. This is due to the endo dimer having greater torsional strain between the bridging CH2 unit and the C5 ring, and therefore having higher energy. This therefore means that the exo dimer (1) is the most thermodynamically stable product. This contradicts the experimental evidence that the endo dimer is only formed during the dimerisation. This data can be seen in Table 1 below:

| Energy /kcalmol-1 | ||

| Energy Contribution |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Stretch |

1.30 | 1.26 |

|

Bend |

20.56 | 20.87 |

|

Stretch-Bend |

-0.84 | -0.83 |

|

Torsion |

7.66 | 9.50 |

|

Non-1,4 VDW |

-1.41 | -1.52 |

|

1,4 VDW |

4.23 | 4.29 |

|

Dipole/Dipole |

0.38 | 0.45 |

|

Total Energy |

31.88 | 34.01 |

This shows that the dimerisation of cyclopentadiene is kinetically controlled as only the kinetic product (2) is formed, due to the reaction being irreversible[2]. This agrees with the endo rule, which states that for Diels-Alder reactions (which the dimerisation of cyclopentadiene is), the most stable transition state occurs when there is a “maximum accumulation of double bonds”[3]. This rule is not always followed, but usually remains true for cyclic dienes and dienophiles, such as the cyclopentadiene dimer.

Hydrogenation of the Cyclopentadiene Dimer

The cyclopentadiene endo dimer can be hydrogenated at either of the two C=C bonds, which leads to molecules 3 and 4 being formed. However, only after prolonged reaction periods[4] will the complete hydrogenation to the tetrahydro product occur, as shown in Figure 2:

| Energy /kcalmol-1 | ||

| Energy Contribution |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Stretch |

1.30 | 1.26 |

|

Bend |

20.56 | 20.87 |

|

Stretch-Bend |

-0.84 | -0.83 |

|

Torsion |

7.66 | 9.50 |

|

Non-1,4 VDW |

-1.41 | -1.52 |

|

1,4 VDW |

4.23 | 4.29 |

|

Dipole/Dipole |

0.38 | 0.45 |

|

Total Energy |

31.88 | 34.01 |

From Table 2, it can be seen that hydrogenation of the C5 ring on the endo dimer (which leads to derivative 3) leads to an increase in the energy of the product. Even though this is an increase of 1.70 kcal mol-1, it is still a thermodynamically disfavoured process. However, hydrogenation of the C6 ring on the endo dimer (which leads to derivative 4), leads to a large stabilisation of the product, as this derivative has a lower energy. This is due to the large decrease in the bend energy of the molecule, which overcomes the increase in the torsonial energy that is seen during hydrogenation.

This can be associated with the fact that the C=C bond in the norbernene ring is more strained than the C=C bond in the cyclopentene ring, due to the bridging methylene group. This would cause the norbernene double bond to be longer and therefore weaker than the cyclopentene double bond, causing derivative 4 to be more easily formed when hydrogenated. Therefore, if the singular hydrogenation of the cyclopentadiene dimer is assumed to be under thermodynamic control, it is clear that the major product of the reaction will be derivative 4 as this is the most thermodynamically stable.

This conclusion is supported by experimental data, which shows that the hydrogenation of the norbernene double bond of the cyclopentadiene dimer has a much higher reaction rate than that of the hydrogenation of the cyclopentene ring.

Stereochemistry of Nucleophilic additions to a pyridinium ring (NAD+ analogue)

Alkylation of the N-methyl Salt of Pyridoxazepinone

| Figure 3: Molecule 5 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Molecule 5 is an optically active derivative of prolinol, which is a chiral amino alcohol[5]. This optically active derivative reacts with the Gringard reagent methyl magnesium iodide to form molecule 6 which has absolute stereochemisty, i.e. the methyl group always attacks from the top of the pyridinium ring.

By using molecular mechanics, molecule 5 was modelled, and by drawing out the molecule in different ways the most stable form of the molecule was determined. For example, to find the most stable form the pyrrolidine ring was first drawn and its energy minimised using the MM2 method. Subsequently, the cycloheptane ring was added and the whole structure's energy minimised and so on. This produced molecule 5 with the most stable structure, which is seen in Figure 3.

It appears that the stability of molecule 5 is influenced by the dihedral angle between the carbonyl group and the pyridinium ring. It was therefore measured for the most stable structure and had a value of 10°.

Subsequently, the energy of the molecule was measured using the MM2 method at different dihedral angles, which were enforced onto the molecule using ChemBio 3D. This data is shown in Figure 4.

It is apparent that the most stable structure of molecule 5 is when the dihedral angle is at 10° above the plane of the pyridinium ring. The structure which had the carbonyl group below the plane of the ring had extremely large total energy values. Despite the fact that the carbonyl group lies above the plane of the ring, this analysis shows that the top face of the molecule is the least sterically hindered face.

The reaction is most likely to proceed via the carbonyl oxygen coordinating to the magnesium of the gringard reagent, followed by nucleophilic attack of the “negatively charged” methyl group at the 4-position of the pyridine ring, as shown in Figure 5. This nucleophilic attack must occur on the same face of the ring that the magnesium is coordinated to. Therefore, the magnesium on the Grignard reagent will coordinate via the top face, leading to the methyl attacking from the same face and giving the absolute stereochemistry shown in Figure 5.

Nucleophilic Attack of Aniline on the N-methyl Quinolinium Salt

| Figure 7: Molecule 7 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Just like the reaction seen with the N-methyl salt of pyridoxazepinone (5), the reaction between the N-methyl quinolinium salt (7) and aniline has high regio- and stereo- selectivity.

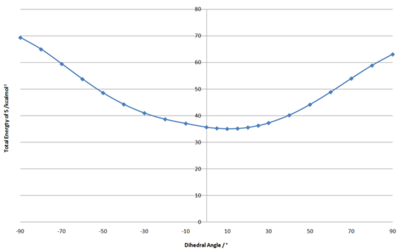

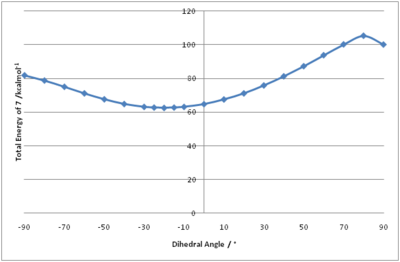

The geometry of molecule 7 was altered and the energy minimised using the MM2 program. This was done several times to determine the dihedral angle of the structure with minimum energy. Once the structure with the minimum energy was determined, the dihedral angle between the carbonyl group and the pyridinium ring was varied between -90° and +90°, and the total energy of molecule 7 was measured. This data was plotted into a graph and can be seen in Figure 6. This shows how the total energy of the molecule changes with the dihedral angle.

This geometrical optimisation and analysis of molecule 7 shows that the lowest energy structure of the N-methyl salt had a dihedral angle of -20°, as seen in Figure 7. This shows that the carbonyl lies below the plane of the aromatic pyridinium ring.

Therefore, the aniline attacks on the opposite face to that which the carbonyl lies above (i.e. the carbonyl lies below the plane of the ring, and therefore the aniline attacks from above the ring). This shows that, unlike the previous example, the carbonyl is not involved in the mechanism of the attack. In fact, the carbonyl sterically and electronically hinders the attack from the bottom face and, therefore, the attack solely occurs from the top face at the C4-position. The mechanism of this reaction is shown in Figure 8.

Stereochemistry and Reactivity of an Intermediate in the Synthesis of Taxol

Atropisomerism

The atropisomers molecules 9 and 10 are key intermediates in the synthesis of Taxol, an anti-cancer drug. The atropisomers are formed via an oxy-Cope rearrangement[6]. Atropisomers are isomers that result from hindered rotations about single bonds. This is due to the unusually high steric demand required to remove the free rotation of the bonds[7].

It was shown by Paquette et al[6] that intermediate 9 spontaneously isomerises to intermediate 10 (Figure 9):

The lowest energy antropisomer was calculated using the programs MM2 and MMFF94, and the results of these calculations are shown in Table 3:

| Energy /kcalmol-1 | ||

| Energy Contribution |

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Stretch | 2.70 | 2.58 |

| Bend | 15.86 | 10.76 |

| Stretch-Bend | 0.40 | 0.32 |

| Torsion | 18.22 | 19.59 |

| Non-1,4 VDW | -1.09 | -1.33 |

| 1,4 VDW | 12.65 | 12.56 |

| Dipole/Dipole | 0.15 | -0.18 |

| Total Energy (MM2) | 48.89 | 44.28 |

| Total Energy (MMFF94) | 70.53 | 60.54 |

For both atropisomers, the cyclohexane ring in the chair conformation gave the most stable structures. However, both atropisomers also exhibit higher energy twist-boat conformations as well. What is interesting is that, in the literature[6], the cyclohexane ring in intermediate 9 has been described as being in the twist-boat conformation. This disagrees with the calculations done which have determined that the chair conformation of intermediate 9 is more stable. Therefore, in this discussion, the chair conformation of intermediate 9 will be discussed.

From the table, it can be clearly seen that intermediate 10 has the lowest energy for both force fields used. What is interesting is that the different force fields do not give the same total energy. The reason for this is because the energies calculated are relative, and therefore cannot be directly compared. It can also be seen that intermediate 9 has higher bending strain than intermediate 10. This is most likely associated with the position of the substituents on the cyclohexane ring. In intermediate 9, they are axial, and therefore there is more repulsion due to 1,3 diaxial interactions, increasing the total energy of the molecule. However, in intermediate 10, the substituents are equatorial, and therefore there is less 1,3 diaxial interaction and the energy of the molecule is slightly lower.

Also, in intermediate 9, the carbonyl is pointing up. This would be expected to have more of a steric clash with the bridging unit and therefore intermediate 9 would be expected to have a higher energy. Finally, the angle of the sp2 carbon of the carbonyl differs greatly between the two molecules. For intermediate 10, it has the expected value of 120°, which is the preferred angle for sp2 carbons. However, for intermediate 9, it has a value of 126°. This obviously makes the molecule much more strained and therefore has higher energy. In conclusion, combining all of these points, intermediate 10 has a lower energy than intermediate 9. Therefore, intermediate 9 will isomerise spontaneously to intermediate 10, which has the carbonyl group pointing below the plane of the ring.

Hyperstability

Hyperstable alkenes are defined as "alkenes which are less strained than the parent hydrocarbon and should show decreased reactivity because of the bridgehead location of the double bond"[8].

This observed stability of bridgehead alkenes, as seen in molecules 9 and 10, is related to the alkene strain which is largely due to twisting around the double bond. This twisting causes the HOMO-LUMO gap to decrease (due to the twisting reducing the π-overlap), and therefore the alkene is stabilised[8]. As a result, the alkene reacts very slowly. This is synthetically very useful, as these hyperstable alkenes will allow other functional groups to be reduced in its presence before it itself is reduced.

Modelling Using Semi-empirical Molecular Orbital Theory

Regioselective addition of Dichlorocarbene

Part 1: Orbtital Control of Reactivity

Due to dichlorocarbene being a very reactive electrophile, it will readily react with alkenes, such as those of 9-Chloro-1,4,5,8-tetrahydro-4a,8a-methanonaphthalene (11). However, it was shown by Halton et al[9] that this reaction occurs with high π-regioselectively, with the major product, the syn mono-adduct, being formed as shown in the reaction scheme below:

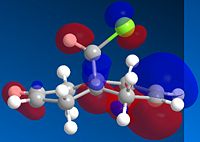

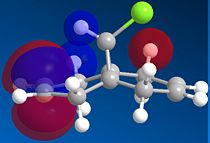

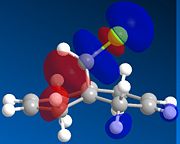

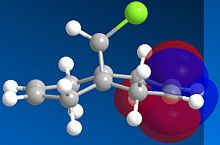

The reactivity of a molecule is determined by its frontier orbitals, i.e. its highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO). Using the PM6/MOPAC method, the above regioselectively has been explained by modelling the approximate molecular orbtials, which can be seen in Table 4:

| HOMO-1 | HOMO | LUMO | LUMO+1 | LUMO+2 |

The reaction of molecule 11 with the electrophilic carbene would be expected to involve the most nucleophilic alkene in the dialkene. This would be the alkene that has the most electron density as shown in its HOMO orbital.

It can be clearly seen that the alkene C=C bond syn to the chlorine has the most electron density in the HOMO orbital. This therefore implies that this alkene is the most nucleophilic and will react with the electrophilic carbene first to form the mono-adduct. This agrees with what is observed in the experimental results[9].

This can also be explained via the anti-alkene bond. The molecular orbital that corresponds to the filled anti-alkene C=C bond is the HOMO-1 orbital. This has a favourable interaction with the LUMO+1 orbital which corresponds to the C-Cl σ* orbital. This interaction stabilises the HOMO-1 level, making it less nucleophilic and therefore it will not attack the electrophilic carbene.

Part 2: Vibrational Frequencies

In order to investigate the how the vibrational frequencies of molecule 11 are affected by the C-Cl bond, its vibrational frequencies were compared with those of its hydrogenated version (molecule 12), which only has a double bond anti to the C-Cl bond. Both molecules are shown in Figure 11.

Table 5 gives the stretching frequencies calculated using the B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) Gaussian geometry optimization and frequency calculation:

| Stretching frequency cm-1 | |||

| Molecule | C-Cl Bond | Syn C=C Bond | Anti C=C Bond |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

770.9 | 1757.4 | 1737.2 |

|

|

775.0 | 1758.1 | N/A |

The stretching frequencies of the C-Cl bonds in both molecules correspond to those of the literature [10]. However, the C=C double bond stretching frequencies are much higher than literature values of 1620-1680cm-1. This is most likely due to the inaccuracy of the procedure used, and could most likely be improved by using full quantum analysis.

For the alkene anti to the C-Cl bond, this higher vibrational frequency can be explained by the destabilistation of the alkene π-orbital due to the overlap with the σ* orbital of the C-Cl bond.

As the anti-alkene has a lower vibrational stretching frequency than the syn-alkene, it implies that the anti-alkene has a lower bond energy, and therefore is a weaker bond. This therefore implies that the syn-alkene is more stable, and therefore has greater electron density. This means it can act as a stronger nucleophile than the anti-alkene. Therefore, this agrees with the molecular orbital discussion which concluded that the syn-alkene is more reactive and therefore reacts first.

With the hydrogenation of the anti C=C bond, the frequencies for the C-Cl bond and the syn C=C bond are slightly shifted to higher wavenumbers, with the C-Cl bond affected more. The reason for this is due to the fact that the σ* C-Cl bond is no longer involved in stabilising the anti-C=C bond. This means that there is less electron density in this σ* bond, making the bond stronger, and therefore the vibrational frequency is shifted to a to higher frequency.

Part 3: Vibrational Frequencies of Substituted Dialkenes

Various substituents were added to the anti C=C bond. The substituents used were –SiMe3, -BH2 and –OH, all shown in Figure 12. The vibrational stretching frequencies of the C-Cl and both C=C bonds are shown in the Table 6 below.

| Stretching frequency cm-1 | |||

| Molecule | C-Cl Bond | Syn C=C Bond | Anti C=C Bond |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

759.0 | 1755.6 | 1657.2 |

|

|

757.2 | 1755.5 | 1688.4 |

|

|

766.8 | 1756.3 | 1776.6 |

For all of the compounds, the vibrational stretching frequency of the syn- C=C bond remains relatively unchanged, which shows that varying the substituent on the anti C=C bond does not influence the strength of the syn C=C bond.

However, the addition of the substituent on the anti-alkene lowers the stretching frequency of the C-Cl bond. This shows that there is a large interaction between the filled π-orbital of the anti-alkene and the σ* C-Cl orbital, which increases the electron density in the antibonding orbital, weakening the C-Cl bond and therefore lowering the stretching frequency. There is also a large difference in the vibrational stretching frequency of the anti C-C bond as the substituent changes. It is clear from the table that electropositive substituents, such as SiMe3, lower the stretching frequency of the anti C=C bond. This is due to the fact that electropositive substituents, such as SiMe3, increase the electron density in the π*-orbital of the C=C bond, via sigma conjugation. This weakens the double bond, and therefore lowers the stretching frequency. Also, due to the fact that SiMe3 is a very bulky substituent, this most likely distorts the geometry of the dialkene, reducing the overlap of the π-orbitals. This makes the double bond less planar and therefore weakens it.

However, with BH2, where B is slightly more electronegative than Si[11], it reduces the stretching frequency of the anti C=C bond even more than SiMe3. This is due to the empty p-orbital on the boron atom accepting electron density from the double bond, significantly weakening the double bond, and lowering the stretching frequency. The hydroxyl substituent it is inductively electron withdrawing, although it donates electrons via resonance. This causes the stretching frequency of the anti- C=C bond to increase, indicating a strengthening of the double bond.

Structure based Mini project using DFT-based Molecular orbital methods

Introduction

Oxazolines are widely seen in natural products and biologically active compounds, especially in marine organisms[12][13] but also in pharmaceudicals[14] as they offer interesting chiral scaffolds for potential lead compounds in drug discovery[15]. When oxazolines are enantiomerically pure, they also act as very efficient chiral ligands for asymmetric transformations[16][17]. They are even useful as intermediates in organic synthesis[18].

Therefore, it is very clear that a cheap and easy method for the synthesis of oxazoline rings with various substituents is a main goal for synthetic chemists.

In the past, the general route to synthesising oxazolines has been the reaction of hydroxyamides with thionyl chlorides via a cyclisation reaction[19]. However this limits the range of substituents that can be easily introduced onto the ring. Consequently, few methods are available for the preparation of diverse 2,4,5-substituted chiral oxazolines[20].

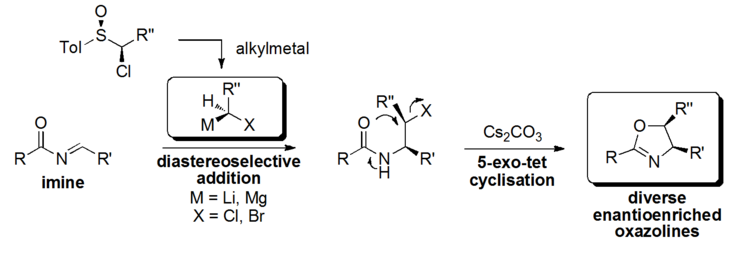

At Imperial College, a novel synthesis of 2,4,5-substituted chiral oxazolines will be developed during the summer of 2011 using the unique reactivity of α-halometal compounds, which are under-exploited in organic synthesis[21]. These reagents undergo initial nucleophilic addition and deliver a halogen for further transformations. This project will employ, for the first time, chiral carbenoid reagents to provide direct access to enantioenriched substituted oxazolines. These will be generated by a sulfoxide-metal exchange which occurs rapidly at low temperatures from α-halosulfoxides (which are easily prepared in excellent enantiomeric excesses by catalytic oxidation)[22].

In this project (Figure 13), α-halolithium structures and magnesium carbenoids will be generated and treated with various N-acyl imines. The initial addition will occur to yield the β-haloamide intermediate highly diastereoselectively with the enantioselectivity controlled by the ee of the carbenoid reagent. Cyclisation through the amide carbonyl to the 5-membered ring will occur under the action of a soft base. This will provide a flexible, modular approach to oxazoline structures bearing diverse alkyl and aryl substituents. A future extension of this approach to the use of ketone derived imines and then to thiazoline and imidazoline structures, is envisaged.

However, as this has never been attempted before, basing the mini project on this would not be possible as no experimental results have been found yet. Thereforem, a different synthesis of 2,4,5-substituted chiral oxazolines was found which has experimental results. This was the direct synthesis of oxazolines from olefins and amides using t-BuOI[23]. This was developed out of the desire to synthesise oxazolines from readily available reagents, such as olefins and amides, yet this had not been developed prior to this research[24]. Tert-butyl hypoiodite (t-BuOI)[25], was previously used by the same research group in the aziridination of olefins with sulfonamides[26]. Based on this, the direct synthesis of oxazolines using t-BuOI was attempted.

This mini project is based on the synthesis of the regioisomers 4-Methyl-2-(p-nitrophenyl)-5-phenyl-2-oxazoline and 5-Methyl-2-(p-nitrophenyl)-4-phenyl-2-oxazoline (Figure 14) in this novel synthesis of oxazolines. It will also utilise the experimental data from Minakata et al[23] and also that of S. Crosignani et al[27]. The aim of this project is to use computational calculations of various molecular properties including 13C NMR, IR and UV/vis to analyse the experimental data of the regioisomers 4-Methyl-2-(p-nitrophenyl)-5-phenyl-2-oxazoline and 5-Methyl-2-(p-nitrophenyl)-4-phenyl-2-oxazoline.

Synthesis of Regioisomers 13 and 14

To a mixture of p-nitrobenzamide (83mg, 0.5 mmol), trans-β-methylstyrene (118mg, 1.0 mmol) and NaI (1.5 mmol) in MeCN (3 mL) was added t-BuOCl (1.5 mmol). The mixture was allowed to stir in the dark at room temperature for 12 hrs under an atmosphere of nitrogen, quenched with 0.3M aqueous Na2S2O3 (3 mL), the solution extracted with CH2Cl2, dried over MgSO4, and concentrated under vacuum. The residue was purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel (eluent: hexane/ethyl acetate)[23].

This reaction produced the regioisomers the orange solid, 4-Methyl-2-(p-nitrophenyl)-5-phenyl-2-oxazoline (13) (65%) and the white solid, 5-Methyl-2-(p-nitrophenyl)-4-phenyl-2-oxazoline (14) (7%). The proposed reaction mechanism is shown in Figure 14[23].

Predicted 13C NMR spectra

Both Minakata et al[23] and Crosignani et al[27] reported the 13C NMR spectra for 14 and 13 respectively. However, neither assigned the signals to the individual carbon atoms. This mini project will complete their assignments.

The 13C NMR spectra were predicted using the Gauge Invariant Molecular Orbital approach (GIAO) with Gaussian density functional theory (DFT). The method that was employed was the mPW1PW91/6-31g (d,p), with the solvent CDCL3. Figure 15 shows how the atoms were numbered and therefore the chemical shifts can be assigned to their respective atoms. The computed results[28][29] are shown in Table 7 as well as the literature values:

|

|

| 13C NMR Chemical Shift / ppm | |||||

| Atom Number |

Predicted |

Literature |

Atom Number |

Predicted |

Literature |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 21.6 | 21.2 | 6 | 20.8 | 20.7 |

| 1 | 74.2 | 71.2 | 1 | 84.9 | 84.9 |

| 5 | 88.9 | 88.8 | 5 | 78.0 | 77.5 |

| 10 | 121.7 | 123.6 | 12 | 121.7 | 123.5 |

| 12 | 122.2 | 10 | 122.1 | ||

| 18 | 121.5 | 125.6 | 18 | 122.5 | 126.6 |

| 14 | 122.9 | 14 | 123.0 | ||

| 16 | 124.6 | 128.6 | 16 | 123.8 | 127.9 |

| 15 | 124.7 | 128.9 | 15 | 124.6 | 128.9 |

| 17 | 125.7 | 17 | 125.5 | ||

| 13 | 126.3 | 129.3 | 9 | 126.4 | 129.4 |

| 9 | 127.7 | 13 | 127.8 | ||

| 8 | 131.9 | 133.6 | 8 | 131.9 | 133.7 |

| 7 | 137.5 | 139.7 | 7 | 139.6 | 141.3 |

| 11 | 145.4 | 149.5 | 11 | 145.5 | 149.6 |

| 3 | 157.9 | 160.9 | 3 | 160.1 | 162.2 |

During the comparison, it was shown that not all of the 13C NMR shifts had been reported by both Minakata and Crosignani. This is most likely due to the fact that the peaks they have reported (highlighted yellow) correspond to carbon atoms in chemically equivalent environments on the phenyl rings. This is most likely due to the fact that, in real life, molecules can rotate around various bonds and therefore carbon atoms become equivalent. However, modelling it with GIAO and DFT does not take this into account and therefore inequivalent environments are calculated.

In general it can be seen that the predicted 13C NMR spectra matches reasonably well to the literature spectra, with the largest difference between the predicted and literature NMR data being 4.1 ppm. This shows that the technique used to calculate the NMR spectra is reasonably accurate. This analysis also shows that the method used to calculate the spectra is more inaccurate when it comes to carbons in aromatic systems, as these produce the largest differences when compared to the literature values. This again is due to the fact that, in real life, the phenyl rings will be rotating or twisting around the various C-C bonds. This would cause inequivalency in the carbon atoms in the phenyl rings. However, the method used calculated the chemical shifts using a static and rigid molecule, so no rotation would be observed.

This 13C NMR data can be used to distinguish between the two regioisomers. The main difference between the two molecules are carbon atoms 1 and 5. In oxazoline 13, carbon atom 5 is adjacent to the oxygen and carbon atom 1 is adjacent to the nitrogen, and vice versa in oxazoline 14. Due to the fact that oxygen is more electronegative than nitrogen, they will cause different amounts of deshielding in the 13C NMR, i.e. carbon atoms adjacent to oxygen atoms will be deshielded more than those adjacent to nitrogen atoms. Therefore, in oxazoline 13, carbon 5 is more deshielded than carbon 1, but this is reversed in oxazoline 14. The difference in these carbon chemical shifts in the regioisomers is about 10ppm. This is sufficiently large to distinguish between the two regioisomers and therefore 13C NMR spectra can be used to distinguish between regioisomers.

Also, the differences between the calculated and reported chemical shifts for carbons 1 and 5 are very small (the largest difference being 3 ppm for carbon 1 in oxazoline 13, and the smallest being 0 ppm for carbon 1 in oxazoline 14). This again shows that the method used to predict the 13C NMR spectra for these oxazolines is accurate enough to distinguish between the two regioisomers.

Predicted IR Spectra

| IR Frequencies / cm-1 | |||||

| Stretch |

Predicted |

Predicted |

Literature | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N-H (Impurity) |

N/A | N/A | 3438 | ||

| C-H | 3049 | 3051 | 2924 | ||

| C=N | 1715 | 1708 | 1645 | ||

| Asym N-O (Nitro) |

1615 | 1615 | 1599 | ||

| C=C (Aromatic) |

1449 | 1450 | 1525 | ||

| Sym N-O (Nitro) |

1397 | 1397 | 1346 | ||

| C-O (Ether) |

999 | 1083 | 1064 | ||

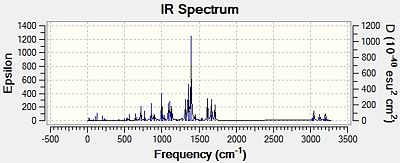

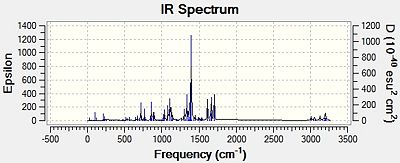

The infra-red spectra of the two regioisomers was also calculated using the b31yp/6-31G (d,p) method. The resulting IR spectra[30][31] are shown in Figure 16 below.

|

|

| Oxazoline 13 | Oxazoline 14 |

| Figure 16: Predicted IR Spectra for Oxazolines 13 and 14 | |

As can be seen, the IR spectra of the two regioisomers are very similar, and this confirms the fact that infra-red spectroscopy cannot be used to distinguish between regioisomers.

However, as shown in Table 8, the calculated infra-red spectra correspond reasonably well with that found in the literature[23]. There are two main differences. The first is that the literature data has a stretch at 3438cm-1. This corresponds to an N-H stretch. This is due to an impurity in the sample, most likely the starting material p-nitrobenzamide.

The second difference is that the frequencies of the calculated spectra are shifted to different wavenumbers compared with those of the literature. This is most likely due to the fact that the calculated IR spectra are for when the oxazolines are in the gas phase. However, the reported IR spectra were run in KBr. Due to using a solvent, the resulting stretching frequencies will have very different wavenumbers associated with them.

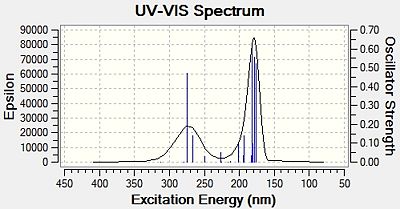

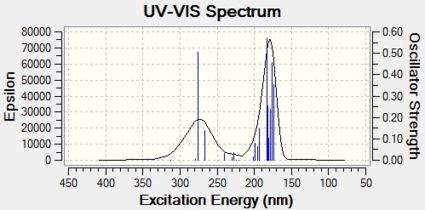

Predicted UV/vis Spectra

It was reported that the two regioisomers had different colours[23]. Oxazoline 13 appeared as an orange solid, whereas oxazolien 14 appeared as a white solid. This seems somewhat confusing as both regioisomers have the same amount of conjugation, and therefore should have similar UV/vis spectra. Therefore the UV/vis spectra of both oxazolines were calculated using the time-dependent DFT method, using the first 20 electronic singlet excitations in the cam-b31yp/6-31g (d,p) method. The resulting UV/vis spectra[32][33] are shown below in Figure 17:

|

|

| Oxazoline 13 | Oxazoline 14 |

| Figure 17: Predicted UV/vis Spectra for Oxazolines 13 and 14 | |

Both UV/vis spectra yield interesting results. Firstly, they appear the same for both regioisomers. This implies that UV/vis spectroscopy cannot be used to distinguish between these regioisomers. Also, they both have absorbances between 150 and 300nm. This is clearly in the ultraviolet range of the electromagnetic spectrum[34]. This implies that neither of the regioisomers absorb in the visible light region and therefore both should appear white. This is seen for oxazoline 14, but not for oxazoline 13, which seems to absorb the blue part of the visible spectrum (as it appears orange). This either means that the method used to calculate the UV/vis spectra is not accurate enough, or that the reaction led to impurities which caused the orange colour. The former seems more likely due to the fact that is has been reported that oxazoline 13 appears orange in colour[35]. In this journal, oxazoline 13 was prepared using different reagents and conditions, and it is very unlikely that the same impurity was formed by two different reactions.

Regioselectivity

Minakata et al mention that the reaction shown above proceeds with the formation of regioisomers 13 and 14, which are easily separable by silica gel[23]. The journal also mentions that the efficiency of forming only one regioisomer needs to be improved. However, the journal does not explain how either of these two points are achieved, and this will be attempted now.

This reaction obviously gave trans-oxazolines exclusively with the retention of the starting olefin, i.e. trans-β-methylstyrene, but the point of attack in the SN2 like manner could not be controlled. The reason for this was not given by Minakata et al. The reason why the formation of 4-Methyl-2-(p-nitrophenyl)-5-phenyl-2-oxazoline (13) is preferred over 5-Methyl-2-(p-nitrophenyl)-4-phenyl-2-oxazoline (14) would be due either to sterics or to electronics.

From a sterics point of view, the attack on the carbon with the phenyl substituent (blue) would be unfavoured as there would be a lot of steric hindrance between phenyl and aryl groups. Therefore, from this point of view, the attack of the methyl substituted carbon (red) would be preferred.

From an electronic point of view, the methyl group is slightly inductively electron donating, whereas the phenyl group is neither electron donating nor electron accepting. This makes the carbon with the methyl substituent slightly more negatively charged (δ-) than the phenyl substituted carbon. Therefore, from this point of view, the attack of the phenyl substituted carbon would be preferred.

Therefore, it can be concluded that, in this reaction, the sterics override the electronics and the major product formed is 4-Methyl-2-(p-nitrophenyl)-5-phenyl-2-oxazoline.

|

|

Doing simple MM2 calculations on the final products shows that oxazoline 13 has a higher energy than oxazoline 14 (the difference being 3.55 kcalmol-1). This implies that despite the prolonged reaction time, this reaction is not under thermodynamic control. It also implies that the product determining step in the mechanism is irreversible. This makes sense as it seems unfavourable to reform the sterically strained iodonium intermediate as well as the divalent nitrogen.

|

|

From this analysis, it seems that the amount of steric hindrance that the substituents have control which reaction is favoured. This could be tested by changing the substituent of the amide. With a non-sterically bulky substituent, such as a methyl group (15), the ratio of the regioisomers (15a and 15b in Figure 18) should be less one sided. On the other hand, if a sterically bulky substituent is used, such as –SiMes3 (16), there would be a very large steric clash between the –SiMes3 and phenyl substituents, which should lead to solely to 15a over 15b (as seen in Figure 19).

Simple MM2 calculations were run on the intermediates that formed the regioisomers of 16, and it did indeed show that the intermediate that forms oxazoline 16a has a slightly lower energy than that of 16b (1.46 kcalmol-1). This shows that the above analysis is in theory correct. However, this theory can only be totally proven by carrying out the reaction.

Conclusion

The computational methods used in this mini-project were able to distinguish between the two regioisomers 13 and 14 by using the predicted 13C NMR data. These also correlated well with the literature values. It was also shown that IR data cannot be used to distinguish between regioisomers. Finally, the predicted UV/vis spectra were not able to explain why oxazoline 13 appears orange whereas oxazoline 14 appears white. This was concluded to be due to the methods used to calculate the UV/vis spectra not being accurate enough. Therefore, a more reliable method needs to be investigated.

Overall Conclusion

In this module both molecular mechanics and semi-empirical molecular orbital theory has been used to accurately and reliably explain both the stereoselectivity and reactivity of various real life experiments in a quick and simple manner.

In the mini project, 13C NMR, IR and UV/vis spectra were calculated to explain the regioselectivity of the synthesis of an oxazoline as well as the appearance of the regioisomers. Finally, it was also seen that all of the data calculated (bar the UV/vis data) strongly correlated with the observed experimental results. This demonstrates how computational techniques can be used not only in verifying experimental results, but also in predicting them.

References

- ↑ P.J. Jr. Wilson, J.H. Wells, Chem. Rev., 1944, 34, 1: DOI:10.1021/cr60107a001

- ↑ J. Sauer, R. Sustmann, Angew. Chem, 1980, 19, 779: DOI:10.1002/anie.198007791

- ↑ K. Alder, G. Stein, Angew. Chem, 1937, 50, 514: DOI:10.1002/ange.19370502804

- ↑ D. Skála, J. Hanika, Pet. Coal, 2003, 45, 105: PDF

- ↑ Dickman, D. A.; Meyers, A. I.; Smith, G. A.; Gawley, R. E. Reduction of α-Amino Acids: L-Valinol Organic Syntheses, 7, p.530 (1990).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 S. W. Elmore and L. Paquette, Tetrahedron Letters, 1991, 319; DOI:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0

- ↑ Bringmann G, Mortimer AJP, Keller PA, Gresser MJ, Garner J, Breuning M, Angewandte Chemie Internation Edition, 2005, 44; DOI:10.1002/anie.200462661

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 W.F. Maier, P.v.R. Schleyer, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1981, 103, 1891: DOI:10.1021/ja00398a003

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 B. Halton, S.G.G. Russell, J. Org. Chem., 1991, 56, 5553: DOI:10.1021/jo00019a015

- ↑ C. N. Banwell, E. M. McCash, Fundamentals of Molecular Spectroscopy, 4th edn., 1994, p.86

- ↑ L. Pauling, The Nature of the Chemical Bond, Cornell Univ., USA, 3rd ed., 1960.

- ↑ R. J. Bergeron, Chem. Rev., 1984, 84, 587–602

- ↑ B. S. Davidson,Chem. Rev., 1993, 93, 1771–1791

- ↑ Nicolaou, K. C.; Liazos, D. E.; Kim, D. W.; Schlawe, D.; de Noronha, R. G.; Longbottom, D. A.; Rodriguez, M.; Bucci, M.; Cirino, G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 4460–4470.

- ↑ Fan, L.; Lobkovsky, E.; Ganem, B. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 2015

- ↑ G. Helmchenand A. Pfaltz, Acc. Chem. Res., 2000, 33, 336–345

- ↑ A. I. Meyers, J. Org. Chem., 2005, 70, 6137–6151

- ↑ T. G. Gant and A. I. Meyers, Tetrahedron, 1994, 50, 2297–2360

- ↑ H. Witte and W. Seeliger, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl., 1972, 11, 287–289

- ↑ Wipf, P. Chem. Rev., 1995, 95, 2115

- ↑ Bull, J. A.; Mousseau, J. J.; Charette, A. B. Org. Synth. 2010, 87, 170

- ↑ Drago, C.; Caggiano, L.; Jackson, R. F. W. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 7221

- ↑ 23.00 23.01 23.02 23.03 23.04 23.05 23.06 23.07 23.08 23.09 Satoshi Minakata et al, Chem Commun, 2007 3279-3281

- ↑ J. Liu and D. Y. Gin, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2002, 214, 9789–9797

- ↑ D. D. Tanner, G. C. Gidley, N. Das, J. E. Rowe and A. Potter,J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1984, 106, 5261–5267

- ↑ S. Minakata, Y. Morino, Y. Oderaotoshi and M. Komatsu, Chem. Commun., 2006, 3337–3339

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 S. Crosignani and D. Swinnen, J. Comb. Chem. 2005, 7, 688-696

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Published 13 NMR Data, DOI:10042/to-7377

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Published 14 NMR Data, DOI:10042/to-7378

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Published 13 IR Data, DOI:10042/to-7379

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Published 14 IR Data, DOI:10042/to-7380

- ↑ Published 13 UV/vis Data, DOI:10042/to-7381

- ↑ Published 14 UV/vis Data, DOI:10042/to-7382

- ↑ Process for Determining Solar Irradiances, http://www.spacewx.com/ISO_solar_standard.html}}

- ↑ Somanathan, Ratnasamy; Aguilar, Hugo R.; Rivero, Ignacio A.; Aguirre, Gerardo; Hellberg, Lars H.; Yu, Zheng; Thomas, Jacquelin A. Journal of Chemical Research, Miniprint, 2001 , 3, 348