Rep:Mod:NMA2613

Introduction

Solving Schrodinger's equation for systems larger than 1-electron systems is not simple and gets increasingly complicated for larger systems. Using computational methods allows the modelling and study of such large systems, though many approximations need to be introduced. Depending on the computational method, these approximations differ, but the aim of any method is to find solutions to the electronic Schrodinger equation. [1] So-called Ab initio methods include Hartree Fock, the simplest wave-function based method which uses the mean-field approximation amongst other approximations (Born-Oppenheimer, Independent Particle and LCAO). [2] This means that it ignores the correlation energy [3]. Methods which take this factor into account are called Correlated and they include DFT (Density Functional Theory), which are based on the electron density distribution rather than the wave-function. [2] [3]. Semi-Empirical Methods are derived from HF but make further approximations as well as partly incorporating correlation energy, which makes them more useful for highly complicated systems where other methods such as HF would be more expensive. [4] In this experiment, HF, DFT and Semi-empirical methods were used to model the transition states of the Cope rearrangement and Diels-Alder reactions, examine possible selectivity and explain reactivity. The first part was focused on the Cope Rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene, where the two possible TS were modelled using different methods (by computing force constants, by using the frozen-coordinate method and by using QST2) and at different levels, namely HF and DFT. In the second part, the focus was on two Diels-Alder reactions: ethene + butadiene and the more complicated system of cyclohexa-1,3-diene + maleic anhydride. These calculations were run using the AM1 semi-empirical method.

Nf710 (talk) 15:17, 11 February 2016 (UTC) Nice concise intro, you have covered most of the main points but still be detailed. you could have possibly spoken about basis sets.

Tutorial: Cope Rearrangement

Reactant and product optimisation

| Conformation | Level of optimisation | Point Group | Electronic energy (hartrees) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti

|

HF/3-21G | Ci | -231.692535 | ||

| Gauche

|

HF/3-21G | C2 | -231.691530 |

The table above shows two of the possible conformations for 1,5-hexadiene, one being anti and the other gauche. By looking at the structure, it would be expected to find that the gauche conformer has a higher energy than the anti conformer given the higher degree of steric clash between the two ends bearing each an alkene. This is an agreement with the electronic energy values found by optimising at the HF/3-21G level (the energy of the anti conformer is larger). The structures shown above are the same as the anti2 and gauche4 structures provided in Appendix 1. Initially it seemed that the anti conformer drawn above is the most stable conformer of 1,5-hexadiene but studies have shown that the lowest energy conformer is gauche and most probably involves a so-called CH/π interaction, [5] whereby the vinyl proton of one of the terminal alkenes interacts with the π orbital of the other, and the geometry required for that stabalising interaction is that of the gauche conformer shown in the table below (referred to as gauche 3 in the appendix provided).

Nf710 (talk) 15:18, 11 February 2016 (UTC) That reference is outdated, you could have shown it by looking at the orbitals in the .chk file

| Conformation | Level of optimisation | Point Group | Electronic energy (hartrees) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gauche3

|

HF/3-21G | C1 | -231.692666 |

Anti conformer: Comparing optimisations at different levels

The anti conformer was optimised at a higher level, namely B3LYP/6-31G*. The geometry obtained from both optimisations are the same (as would be expected) but differences are observed in bond lengths and angles. These differences are illustrated in the table below. There is no point in comparing the energy values obtained from different levels of optimisation as HF will always over-estimate the energy relative to DFT. The B3LYP/6-31G* gave an energy of -231.69266 hartrees. HF over-estimates the energy by a value called correlation energy. This energy arises from the fact that the positions of two electrons over time are 'correlated' because of the coulombic repulsion between them. [3]

Nf710 (talk) 15:20, 11 February 2016 (UTC) HF has a higher colomb repulsion because the electrons of parralell spin in the same spatial orbital can exits in the same place. good understanding

| Dihedral: C1-C3-C6-C9 (°) | C14-C1-C3 & C6-C9-C11 (°) | C=C Å (C9-C11) | C3-C6 (Å) | Atom labels | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HF/3-21G | 180.000 | 124.806 | 1.316 | 1.553 |

|

| B3LYP/6-31G* | 180.000 | 125.284 | 1.333 | 1.549 |

Anti conformer: Frequency calculation

The aim of running a frequency calculation on a minimum is to confirm that the structure obtained does in fact correspond to an energy minimum on the Potential energy Surface. The frequency calculation corresponds to obtaining the second derivative of the PES. When optimising a minimum-energy structure, the second derivative is the same as the vibrational force constant k. [6] Hence, the second derivative (or k) must be positive if we are computing a minimum, which is the case here and can be confirmed by looking at the vibration frequencies which were outputted when a frequency calculation at the B3LYP/6-31G* level was run. The log file can be found here. Furthermore, the log file from a frequency calculation contains important information about the energy of the structure. Namely, it contains a section titled 'Thermochemistry' which includes the data shown below:

Sum of electronic and zero-point Energies= -234.469219 Sum of electronic and thermal Energies= -234.461868 Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies= -234.460923 Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies= -234.500814

These are the result of applying corrections to the total electronic energy value, [7] which is shown in the Results -> Summary window. This data will be used to calculate activation energies (see later).

Transition State optimisation

The starting point for optimising a transition state is to find a guess structure. After that, there are several ways to conduct a TS optimisation. Below, the chair TS was optimised via two ways (which lead to the same result), and the boat TS was optimised in a third way. The guess TS was built based on a C3H5 allyl fragment, which was optimised at the HF/3-21G level (see structure in figure below and log file here).

Chair Transition Structure

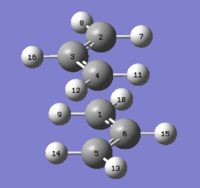

To construct the chair TS from the allyl fragment, two fragments were positioned as shown below.

| inter-fragment distance at terminal C (Å) | all C-C bonds (Å) | TS guess structure (side view) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before optimising | 2.274 and 2.254 | 1.401 |

|

| After optimising | 2.020 and 2.021 | 1.390 |

Optimise TS by computing force constants

This structure was then optimised at HF/3-21G to a TS (Berny) (a frequency calculation was conducted simultaneously using Opt+freq). After optimising a TS using this method, the presence of one negative frequency confirms that we optimised a Transition State (as opposed to a minimum) and the vibration corresponding to that imaginary frequency should correspond to the transition state (i.e. it should illustrate reactant and product vibrating in the direction required to obtain a correct approach for reaction). In fact, the minus sign is simply used to indicate that the frequency in question is imaginary. Having an imaginary frequency is the result of having a negative force constant (second derivative of PES) when we are at a maximum on the PES (i.e. at a TS). Vibrational frequencies are calculated from force constants using: , and in Gaussian, when k<0, the absolute value of k is used and the result multiplied by -1. [8]The negative vibration obtained was and its animation is shown below:

Optimise TS using Frozen Coordinate Method

The idea behind this method is to initially 'freeze' the distance between the two allyl fragments at both ends of the fragments, then to run an optimisation as a minimum. After that, the inter-fragment distances are 'unfrozen' and the structure optimised as a TS (Berny), but without computing the force constants. The aim behind this last optimisation is to find the inter-fragment distance that gives the structure with the highest energy. The data from the two methods used to optimise the chair TS is summarized in the table below for comparison:

| Method | Computing k (force constant) | Frozen Coordinate Method |

|---|---|---|

| Optimisation Level | HF/3-21G | HF/3-21G |

| Log file | here | here |

| Inter-fragment distance at terminal carbons (Å) | 2.021 and 2.020 | 2.021 and 2.021 |

| Total electronic energy (hartrees) | -231.619322 | -231.619322 |

| Total electronic energy () |

Boat Transition Structure

Optimise TS using QST2 method

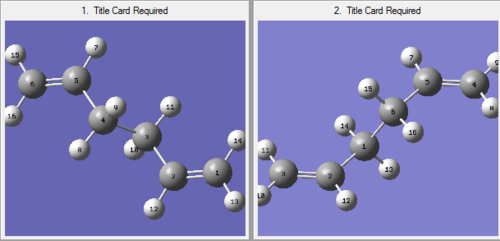

This method is based on specifying the reactant (here, taken as the anti conformer) and product structures in Gaussview, which then finds the structure of the corresponding Transition State. However, two details are very important: the first is that reactant and product molecules must be numbered in the same way and the second is that their geometry must resemble the guess TS geometry. In fact, when reactant and Product were numbered as shown below and optimised using QST2 at HF/3-21G level, the optimisation failed and the outcome resembled the chair TS (log file here). Hence, bond angles were adjusted so as to position the two molecules in such a way that they resemble the boat TS.

| Before adjusting geometry | After adjusting geometry (Boat-like) |

|---|---|

|

|

| Optimised Boat TS | ||

|---|---|---|

Nf710 (talk) 15:28, 11 February 2016 (UTC) No frequency

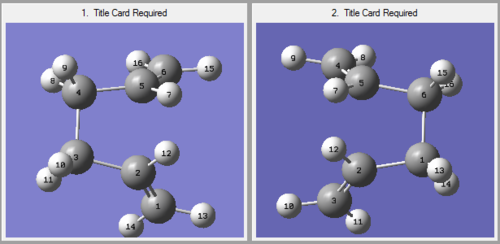

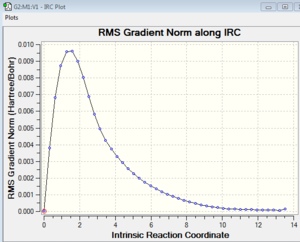

Minimum Energy pathway from the TS

The Intrinsic Coordinate Method in Gaussian allows us to follow the minimum energy pathway from TS to product. Starting from the chair TS optimised by computing the force constants, an IRC calculation was run in one direction for 50 steps. Two plots can be viewed from the results tab (see below).

| Total Energy (hartrees) against IRC | RMS Gradient (hartree/bohr) against IRC | Product Structure (gauche 2 in Appendix provided) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

The plot on the left shows that we are going from a maximum energy species (i.e. TS) and moving toward the product at lower energy. The plot on the right shows how the gradient (i.e. first derivative) varies: it is 0 at the TS (a maximum), then it increases quickly before decreasing until it gets close to 0 again when it reaches a minimum (product). The structure of the product obtained is that labelled 'gauche 2' in the appendix provided. It can be argued that this product is the kinetic product while the lowest energy conformer 'gauche 3' is the thermodynamic product.

Nf710 (talk) 15:29, 11 February 2016 (UTC) Correct conformer identified

Activation Energies

In order to calculate the activation energy for the Cope Rearrangement reaction, initially the TS and reactant structures optimised at HF/3-21G need to be optimised at the B3LYP/6-31G* level to have a more accurate estimation of the energies. This is done by subtracting the energy of the reactant from that of the TS at 0 K (including the correction for the zero point energy, found in the Thermochemistry section of the log files). At 298 K, the correction for thermal energy must also be included. The 'thermochemistry' data needed are summarized in the table below, and the activation energies are shown in the other table. The summary illustrates once again how the energy values differ significantly depending on the level of the optimisation seeing as the HF method significantly over-estimates the energy. However, comparing the geometries of the optimised TS structures at both levels shows that the difference in geometry is not significant (the optimised structures of the 'Anti' reactant at both levels were compared in section 1.1.1. in the report).

Summary of thermochemistry data

| HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All energies in hartree | Electronic Energy | Electronic + 0 point energies | Electronic + thermal energies | Electronic Energy | Electronic + 0 point energies | Electronic + thermal energies |

| 0 K | 298.15 K | 0 K | 298.15 K | |||

| Chair TS | -231.619311 | -231.466701 | -231.461341 | -234.556983 | -234.414929 | -234.409009 |

| Boat TS | -231.602802 | -231.450929 | -231.445300 | -234.543093 | -234.402330 | -234.395995 |

| Reactant (anti 2) | -231.692535 | -231.539539 | -231.532565 | -234.611710 | -234.469219 | -234.461868 |

Calculating Activation Energies

| HF/3-21G | HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G* | B3LYP/6-31G* | Expt | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 K | 298 K | 0 K | 298 K | 0 K | |

| ΔE (Chair) hartree | 0.072838 | 0.071224 | 0.054290 | 0.052859 | |

| ΔE (Chair) | 45.70 | 44.69 | 34.07 | 33.17 | 33.5 ± 0.5 |

| ΔE (Boat) hartree | 0.088610 | 0.087265 | 0.066889 | 0.065873 | |

| ΔE (Boat) | 55.60 | 54.76 | 41.97 | 41.36 | 44.7 ± 2.0 |

Geometry Comparison

| C-C bonds (Å) | inter-fragment distance (Å) | TS Structure | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chair | HF/3-21G | 1.389 | 2.020 |

|

| B3LYP/6-31G* | 1.408 | 1.968 | ||

| Boat | HF/3-21G | 1.381 | 2.140 |

|

| B3LYP/6-31G* | 1.393 | 2.205 |

Comparison with the experimental values confirms once more that optimising at the B3LYP/6-31G* level provides an approximation that is much closer to what is observed in reality in terms of energy values. However, HF remains a useful method for visualising geometries as it is very similar to B3LYP/6-31G* in that respect. The difference in energy between the two types of TS is due to the involvement of different types of strain: in the boat TS, which can be compared to the boat conformation of cyclohexane, there is trans-annular strain (or flagpole interaction) between the two hydrogens pointing towards each other across the ring, torsional strain given the presence of eclipsed C-C bonds. [9]. The chair conformation minimises all these interaction and is thus lower in energy.

Nf710 (talk) 15:36, 11 February 2016 (UTC) your energies are correct, and you have done done most of the things that were asked of you. you have also shown a decent understanding of the theory.

Diels-Alder Cycloaddition

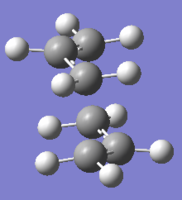

The aim of this second section of the experiment is to initially optimise the structure of the TS for the ethene/ cis-butadiene cycloaddition. This is done by initially optimising the structures of each component separately then combining them to build the guess structure. All optimisations for this section are performed at the AM1 Semi-Empirical level.

Cis-butadiene and ethene

The log files for the optimisation of ethene and cis-butadiene are given below. The symmetry of the HOMO and LUMO of each componenet with respect to the plane in black is also indicated.

| Log file | Results Summary | HOMO shape & symmetry | LUMO shape & symmetry | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cis-butadiene |

|

|

|

| ||

| Ethene |

|

|

|

|

TS of Cis-butadiene + ethene Diels-Alder

The log file for the optimised TS is shown below. There was only one imaginary frequency found (), confirming that the optimised structure is a TS.

| Log file | Summary | HOMO shape & symmetry | LUMO shape & symmetry | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

In terms of the geometry of the TS, the key bond distances (after optimisation) are summarised below:

| Inter-fragment distance (Å) | Ethene C=C (Å) | Cis-butadiene terminal C-C (Å) | Cis-butadiene central C=C (Å) | Experimental C-C (Å) [10] | Experimental C=C (Å) [10] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.119 | 1.383 | 1.382 | 1.397 | 1.542 | 1.338 |

| Imaginary Frequency () | Lowest positive frequency () | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Looking at the table above, it can be seen that the C=C distances of free ethene and cis-butadiene are longer than in the TS, and the central C-C bond in free butadiene is shorter than in the TS. This illustrates the lengthening of the double bonds as they are transformed into single bonds and the shortening of the single bond as it turns into a double bond. Furthermore, the inter-fragment distance, which is where the two new σ bonds will be formed, is shorter than twice the van der Waals radius of Carbon, which is 1.70 Å, [11], though significantly longer than a C-C single bond. This indicates that the TS is reactant-like, meaning that it is an early TS. Looking at the vibration frequencies, the imaginary frequency shows a symmetrical approach between the two components, indicating that it is a synchronous reaction. This is as expected from looking at the reactants, which are symmetrical. An asynchronous DA reaction would be expected if the reactants were not symmetrical, creating a difference in the partial charge on the terminals of the diene and dienophile. This would mean that the reaction, despite being concerted, would be initiated by the preferential formation of one of the two σ bonds, which would promote the formation of the second one. In this case, the TS would be unsymmetrical and running a population analysis on Gaussian would allow to quantify the partial charge on the reacting species. Given the symmetry of the reaction being considered here, population analysis and examination of charge distribution are not necessary. The lowest positive frequency involves twisting of the two components. This vibration is not related to the TS, but can be described as synchronous as it is symmetrical.

Comparing the HOMO of the TS with the HOMO/LUMO of free ethene and cis-butadiene, it can be seen that the TS HOMO is formed from the HOMO of cis-butadiene and the LUMO of ethene. The reaction is allowed because both are antisymmetric with respect to the plane shown in the correponding images.

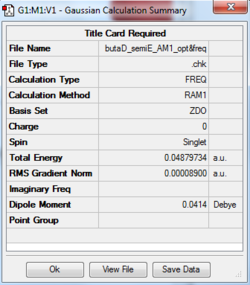

Cyclohexa-1,3-diene and maleic anhydride

The aim of this part of this experiment was to examine the geometries and relative energies of the exo and endo transition states in the Diels-Alder reaction between Cyclohexa-1,3-diene and maleic anhydride. The log files for both optimised transition states are shown below. The method used was AM1 semi-empirical.

| TS | Log file | Results Summary | Imaginary frequency | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endo |

|

||||

| Exo |

|

In order to calculate activation energies for this reaction, cyclohexa-1,3-diene and maleic anhydride were optimised at the AM1 semi-empirical level. The log files for each can be found here and here, respectively.

Summary of thermochemistry data and Calculating Activation Energies

| AM1 semi-empirical | ||

|---|---|---|

| 0 K | 298 K | |

| ΔE (Endo) hartree | 0.044300 | 0.044841 |

| ΔE (Endo) | 27.798676 | 28.138158 |

| ΔE (Exo) hartree | 0.045689 | 0.046042 |

| ΔE (Exo) | 28.670287 | 28.891797 |

| AM1 semi-empirical | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| All energies in hartree | Electronic Energy | Electronic + 0 point energies | Electronic + thermal energies |

| 0 K | 298.15 K | ||

| Endo TS | -0.051505 | 0.133493 | 0.143682 |

| Exo TS | -0.050420 | 0.134882 | 0.144883 |

| Cyclohexa-1,3-diene | 0.027958 | 0.152539 | 0.157034 |

| Maleic anhydride | -0.121824 | -0.063346 | -0.058193 |

| Relative Energy () | ||

|---|---|---|

| 0 K | 298 K | |

| Endo | 0 | 0 |

| Exo | 0.871611 | 0.753639 |

The calculated activation energies above show that the exo TS is higher in energy relative to the endo TS, making the endo product the kinetic product. However, looking at the relative energies of the two transition states at 0 K and 298 K shows that at higher T, the difference in energy between the two transition states is lowered (see later). Considering the steric hindrance in each TS allows to explain the fact that the exo product is higher in energy: looking at the image on the right, it can be seen how the exo TS places an sp3 carbon on the side of the (O=C)-O-(C=O) fragment, bringing the hydrogens closer to that fragment due to the tetrahedral geometry of the carbon, thus increasing steric clash. On the other hand, in the endo TS, that same carbon is sp2 (planar), thus the hydrogen substituents are further away from the (O=C)-O-(C=O) fragment. In summary, in the exo TS, strain is lower than strain, whereas the situation is reversed in the endo TS. It can be assumed that strain is more important as it involves larger O atom nuceli bearing lone pairs, as opposed to clash of H atom nuclei in , making the exo form more strained.

(I'm not familiar with this notation but I know what you're saying Tam10 (talk) 12:06, 11 February 2016 (UTC))

Examination of the Molecular Orbitals of the TS provide an explanation for the stability of the endo TS relative to the exo. Both endo and exo additions are symmetry allowed: the HOMO of cyclohexa-1,3-diene and the LUMO of maleic anhydride are antisymmetric; the LUMO of cyclohexa-1,3-diene and the HOMO of maleic anhydride are symmetric. Hence, as seen previously in the example of ethene and butadiene, ans as expected from a 'normal' electron demand DA reaction, the reaction will occur between the HOMO of the diene and the LUMO of the dienophile. This is confirmed by comparing the HOMO/LUMO pairs of the two transition states with those of the reactants, all shown in the table below. For example, the HOMO of the endo TS is formed from the HOMO of cyclohexa-1,3-diene and the LUMO of maleic anhydride, though the latter differs slightly from the LUMO of free maleic anhydride as the (O=C)-O-(C=O) fragment becomes bent to minimise clash with the incoming diene, so the p orbitals on the carbons of that fragment no longer have the correct symmetry to overlap with the p orbitals of the dienophile fragment.

As for the stabalisation of the endo TS relative to the exo TS, this is attributed to Secondary Orbital Interactions, where the p orbitals of the carbons in the (O=C)-O-(C=O) fragment interact with the LUMO of cyclohexa-1,3-diene. [12] However, this interaction does not lead to the formation of a bond and is observed in the HOMO+2 orbital of the endo TS (as shown on the right), so it is not a significant effect though it does make the endo TS lower in energy than the exo TS. [13] Returning to the observation that the energy difference between the two transition states is smaller at higher T, it can be rationalised considering that the secondary orbital interaction and steric issue become less significant at higher energy, reducing the gap between the two transition states. If enough energy is present, the reaction becomes reversible (thermodynamic control) and lead to the formation of the exo (thermodynamic) product.

(Did you calculate reaction energies to prove that exo is the thermodynamic product? There's actually enough strain in the exo to push it higher in energy than endo Tam10 (talk) 12:06, 11 February 2016 (UTC))

Endo and Exo TS: HOMO and LUMO

| HOMO Front view | HOMO Side view | LUMO Front view | LUMO side view | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endo |  |

|

|

|

| Exo |  |

|

|

|

| Secondary Orbital Interaction (Endo HOMO+2) | |

|---|---|

| Front view | Side view |

|

|

| HOMO | LUMO | |

|---|---|---|

| cyclohexa-1,3-diene |  |

|

| Maleic anhydride |  |

|

Conclusion

This experiment has allowed to demonstrate the advantages and limits of some of the main computational methods via modelling transition states and reactions. It allowed to quantitatively describe the transition states and reactions in question via the calculation of activation energies. Further areas of investigation include attempting to quantify the different types of strain in the cope rearrangement transition structure by introducing different substituents with different sizes and electronegativities. Also, in the case of the DA reaction, the transition structures from unsymmetrical reactants can be modelled to study asynchronous reactions and performing population analysis will allow to quantify charge-distribution and thus examine the regioselectivity of the DA reaction, as opposed to its stereoselectivity which was the focus here.

References

- ↑ R. A. Friesner, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A, 2005, 102, 6648-6653 DOI:10.1073/pnas.0408036102

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 A. Gilbert, presented as a lecture within the Research School Of Chemistry, Australian National University, http://rsc.anu.edu.au/~agilbert/gilbertspace/uploads/Chem3108.pdf, 2007

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Wikipedia. Electronic Correlation, 2015, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Electronic_correlation [Accessed: January 2016]

- ↑ Wikipedia. Semi-empirical quantum chemistry method , 2015, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Semi-empirical_quantum_chemistry_method [Accessed: January 2016]

- ↑ B. W. Gung, Z. Zhu and R. A. Fouch, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1995, 117, 1783-1788 DOI:10.1021/ja00111a016

- ↑ P. Hunt. Frequency analysis of H2O, http://www.huntresearchgroup.org.uk/teaching/teaching_liquids_year4/6_frequency_analysis.html [Accessed: January 2016]

- ↑ J. W. Ochterski. Thermochemistry in Gaussian, 2000, http://www.gaussian.com/g_whitepap/thermo.htm [Accessed: January 2016]

- ↑ J. W. Ochterski. Vibrational Analysis in Gaussian, 1999, http://www.gaussian.com/g_whitepap/vib.htm [Accessed: January 2016]

- ↑ J. Ashenhurst. Ring Strain in Cyclopentane and Cyclohexane, http://www.masterorganicchemistry.com/2014/04/18/ring-strain-in-cyclopentane-and-cyclohexane/ [Accessed: January 2016]

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 H. J. Bernstein, Trans. Faraday Soc., 1961, 57, 1649-1656 DOI:10.1039/TF9615701649

- ↑ A. Bondi, J. Phys. Chem., 1964, 68, 441-451 DOI:10.1021/j100785a001

- ↑ R. Hoffmann and R. B. Woodward, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1965, 87, 4388-4389 DOI:10.1021/ja00947a033

- ↑ I. Fleming, Molecular Orbitals and Organic Chemical reactions, John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, 2010

Note

Some of the log files are attached as Jmol but via a pop-up, rather than on the main page because it became slow to load. I couldn't find a way to adjust the frame to display the minimised structure and I didn't have time to do it otherwise.