Rep:Mod:NK1995

Introduction

This computational experiment involves the locating and study of energy minima and transition structures on a potential energy surface (PES) for a range of pericyclic reactions. The pericylic reactions being investigated in this study include the Cope rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene; [4+2] Diels-Alder cycloaddition of ethene and cis-1,3-butadiene; the exo and endo [4+2] Diels-Alder cycloaddition of maleic anhydride and 1,3-cyclohexadiene. All the pericyclic reactions which are studied in this computational experiment are thermally allowed as they comply with the rule,the total number of (4q+2)s +(4r)a components must be odd [1]. The 'q' and 'r' represent the number of electrons (either π or σ) involved in the reaction of each component, whereas 's' and 'a' represent suprafacial and antrafacial respectively which indicate the symmetry in which orbitals interact.

Computational chemistry is important in the study of these pericyclic reactions for two reasons:

- It enables the total energy of the different species to be calculated which can enable the energy of different species to be compared.

- It is able to locate and calculate the energy of the transition state, which allows the transition state to be studied. This is significant as it provides information on the mechanism of the reaction pathway.

This cannot be achieved through experimental methods, as only energy changes can be calculated experimentally. Also, as the transition state corresponds to an energy maximum in the reaction pathway, it is unstable, giving it a lifetime which is too short to be observed experimentally.

In this study, the Gaussview programme is used to calculate the total energy of species and optimize the structure to locate specific points on a PES. The points which are located include the minima which correspond to stable conformers, and maxima which corresponds to the transition state. The Gaussview programme calculates the total energy by solving the Schrodinger equation using 3 different basis sets: Hartree-Fock/3-21G; Density funtional theory(DFT)/B3LYP/6-31G(d) and Semi empirical/AM1. This study involves 3 different optimization processes. The first optimization process is the 'minimum' optimization process and this locates a local minimum on the PES which corresponds to a stable conformer/species. The other two optimization processes are the 'TS Berny' and the 'Quadratic synchrous transit 2 (QST2)' optimization process and these are used to locate the transition state of the reaction pathway.

The Cope rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene

Background

The Cope rearrangement is a concerted pericyclic reaction which involves a [3,3] sigma tropic rearrangement in which one sigma bond breaks and another sigma bond forms at a different position. The Cope rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene is thermally allowed as there are two π2s components and one σ2s component, which follows the Woodward Hoffman rule of (4q+2)s +(4r)a being odd for a reaction to be thermally allowed. The reaction mechanism for the Cope rearrangment of 1,5-hexadiene can be seen in the figure below.

This reaction has been studied extensively through experimental and computational chemistry methods and it is believed that the reaction proceeds via either the ‘chair’ or the higher energy ‘boat’ transition structure which suffers from torsional strain and flagpole interactions.[2] The first part of this computational study involves using 1,5-hexadiene to study the Cope rearrangement. This involves performing a minimum optimization to locate minima on the PES which correspond to stable conformers of 1,5-hexadiene, and using the TS Berny and QST2 optimization to find the chair and boat transition structures which are then subsequently analysed to determine the favored reaction pathway.

The Hartree-Fock/3-21G and Density funtional theory(DFT)/B3LYP /6-31G(d) basis sets are used to calculate the energy of the different conformers and transition states of 1,5-hexadiene, then from the energy of the reactant and transition state, the activation energy can be obtained.

The calculation methods used to obtain the total energy involve solving the Schrodinger equation, however the Schrodinger equation cannot be solved exactly due to the instantaneous interactions between electrons, as a result a series of approximations need to be used in the calculations. Due to different basis sets having different approximations and different energy scales, the results obtained from using different basis sets cannot be compared.

Hartree-Fock/3-21G involves evaluating the energy of an electron in a molecular orbital moving in a mean field of all the other electrons whereas DFT/B3LYP/6-31G(d) focuses on the electron density of an electron as the central variable to obtain information. They are both similar as they both take into account the kinetic energy of electrons, electron-nuclei interaction and the coulomb potential between electrons.However Hartree-Fock/321-G does not take into account the exchange correlation as in Hartree-Fock/3-21G, electrons of opposite spin can be in the same position at the same time, which is incorrect. As a result of this, the energy obtained from Hartree-Fock/321-G is always above the exact energy.

Nf710 (talk) 19:14, 10 February 2016 (UTC) this is due to the increased coulomb repulsion. Good understanding of electron correlation and the levels and the two levels of theorey nice intro.

Optimizing the reactants and products for 1,5-hexadiene

Due to there being three free rotating C-C bonds in 1,5-hexadiene, there are 10 energetically distinct different conformers that can be formed[3]. In order to optimize the reactants and products, the minimum optimization process was used.

Optimizing the conformers of 1,5-hexadiene using the HF/3-21G method

Firstly, a 1,5-hexadiene molecule was made using the gaussian programme and the dihedral angle of the central four carbons were modified to 180 degrees to ensure that there was a anti-periplanar conformation which corresponds to an anti conformer, the anti conformer that had formed, was the anti4 conformer. The same process was repeated however the dihedral angle of the central four carbons was set to 60 degrees in order to form a gauche conformer, which was the gauche5 conformer.The gauche3 and anti2 conformers of 1,5-hexadiene was then made by the same process with some adjustments to the dihedral angle. The results are summarized in the table below.

| Conformer | Structure | Point group | Energy/Hartrees | Results summary | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti2 | Ci | -231.69253528 |

| |||

| Anti4 | C1 | -231.69097055 |

| |||

| Gauche3 | C1 | -231.69266122 |

| |||

| Gauche5 | C1 | -231.68961573 |

|

From the table, it can be seen that the anti2 and anti4 are more stable than gauche5 as the energy for anti conformers are lower than that of gauche5. This is due to the greater steric hindrance of a gauche linkage as the bulky alkenyl groups groups attached to C3 and C4 are 60 degrees apart in a gauche linkage whereas, the alkenyl groups are 180 degrees in an anti linkage. The gauche3 conformer was the global minima even though it had greater steric hindrance than the anti conformers. The gauche3 conformer was the lowest energy conformer either due to an attractive interaction being present between the π orbitals of one alkenyl group and a vinyl proton on the other alkenyl group[3] or as a result of a π-π interaction between the double bonds in the gauche3 conformer which is not present in the anti2 and the other conformers of 1,5 cyclohexadiene. This π-π interaction can be seen in the molecular orbtials diagram of gauche3 which is shown below.

Nf710 (talk) 19:15, 10 February 2016 (UTC) nice use of the orbitals to show the energy ordering.

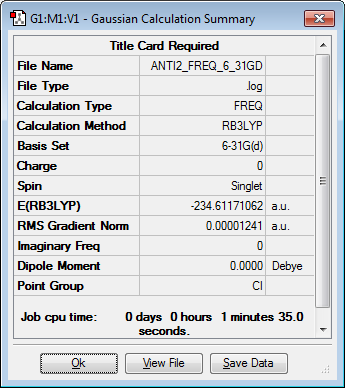

Re-optimizing the anti2 conformer of 1,5-hexadiene using the B3LYP/6-31G(d) basis set

The anti2 was re-optimized at the B3LP/6-31G(d) level with the results shown in the table below.

| Conformer | Structure | Point group | Energy/Hartrees | Results summary | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti2 | Ci | -234.61171062 |

|

Both the structure from the calculation with the Hartree Fock/3-21G and the B3LYP/6-31G(d) basis set have the same point group showing that there has not been a significant change in geometry, however there has been a slight change in geometry which can be seen by analyzing the bond lengths and the dihedral angle of the two structures. The tables showing the bond lengths and the dihedral angles of the anti2 conformer calcuation at the different basis sets are shown below. The bonds lengths and dihedral angles in the tables correspond to atoms labelled in figure 4 and 5, which show the anti2 conformer at the different basis sets.

Comparison of bond lengths

| Bond Lengths (Å) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Atoms | HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G(d) |

| C1-C2 | 1.31614 | 1.33350 |

| C2-C3 | 1.50893 | 1.50419 |

| C3-C4 | 1.55280 | 1.54816 |

The calculation from both the basis sets make clear distinctions between the length of a C-C single and C-C double bond, however the B3LYP/6-31G(d) basis set gives a longer C1-C2 double bond and and a shorter C3-C4 single bond than the corresponding bond from the HF/3-21G calculation. The bond distances using the B3LYP/6-31G(d) basis set agrees more strongly with the literature values of C1-C2 bond length being 1.34Å, C2-C3 being 1.51Å and C3-C4 being 1.54Å[4]. This shows that the B3YLP/6-31G(d) basis set gives more accurate bond distances than the HF/3-21G basis set due to taking into account the exchange correlation when solving the Schrodinger equation.

Comparison of dihedral angles

| Dihedral Angle (°) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Atoms | HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G(d) |

| C1-C2-C3-C4 | 114.66442 | 118.59949 |

| C2-C3-C4-C5 | 180.0000 | 180.00000 |

The C1-C2-C3-C4 dihedral angle is close to the expected 120 degree angle which is expected at an sp2 hybridized carbon which has a trigonal planar arrangement. However it can clearly be seen that the B3LYP/6-31G(d) was once again more accurate than the HF/3-21G calculation method as the B3LYP/6-31G(d) angle was closer to 120 degrees.

Frequency analysis of the anti2 conformer of 1,5-hexadiene at the B3YLP/6-31G(d) level

In order to calculate the vibrational frequencies of a molecule, the second derivative of the energy with respect to the internuclear position must be found to calculate the force constant,k. After the force constant is calculated, the frequency can be obtained by the following equation:

- where μ is the reduced mass of the molecule. For a molecule that is at the minimum of its PES, only real vibrational frequencies would be seen in the infrared spectra due to the force constant/curvature being a positive value at the minimum. If the structure is that of a transition state, the molecule would be at a maxima of its PES and so the force constant/curvature calculated would be a negative value. As a result of a negative force constant being obtained, the vibrational frequency obtained at the transition state would be an imaginary frequency as the vibrational frequency depends on the square root of the force constant.

A frequency calculation on the anti2 conformer of 1,5-hexadiene ran at the BLY3P/6-31G(d) level. As all the vibrational frequencies were positive, which can be seen from the infrared spectra (figure 7), it shows that the anti2 conformer was at a minimum on the PES. This was further proven due to the absence of an imaginary frequency, which shows that the anti2 conformer was not at a transition state.

Nf710 (talk) 19:18, 10 February 2016 (UTC) Good understanding but it is not internuclear position it is relative to that degree of freedom which constitues to a possible change in the energy.

Thermochemical Analysis of the anti2 conformer of 1,5-hexadiene

| 298K(Hartree) | 0K(Hartree) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sum of Electronic and Zero-Point Energies | -234.469219 | -234.469219 |

| Sum of Electronic and Thermal Energies | -234.461869 | -234.469219 |

| Sum of Electronic and Thermal Enthalpies | -234.460925 | -234.469219 |

| Sum of Electronic and Thermal Free Energies | -234.500809 | -234.469219 |

Optimizing the "Chair" and "Boat" Transition Structures

In order to calculate the activation energy, it is necessary to optimize both the reactant and the transition state of a reaction pathway. As the reactant, the anti2 conformer of 1,5 hexadiene conformer, was successfully optimised, it was then necessary to optimize the transition state. In the Cope rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene, there are two possible transition state structures, the chair and the boat. In this study, both transition state structures were optimized. The chair transition state was optimized by two variations of the TS Berny optimization process which were the guess transition structure approach and the freeze co-ordinate approach, whereas the boat transition state was optimized by the QST2 optimization process. The guess transition structure approach involves making a structure that is similar to the transition state of the reaction and then using the TS Berny optimization process to optimize this guess transition state structure into the transition state. The frozen co-ordinate approach involves fixing a specific variable of the structure and optimizing the rest of the molecule, then performing a second optimization on the variable which was fixed in the first optimization.

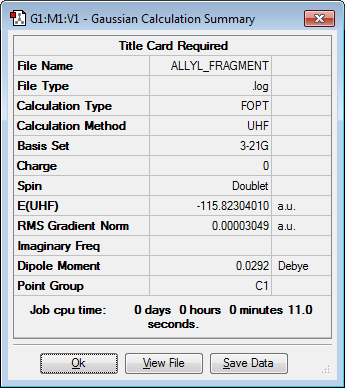

Optimizing the allyl fragment

As the chair and boat transition structures consist of two allyl fragments at a distance of approximately 2.2 Å apart, it would be appropriate to make a guess transition structure out of two allyl fragments. Therefore it was first necessary to optimize an allyl fragment to make this guess transition structure. The allyl fragment was optimised using a minimum optimisation and a Hartree Fock/3-21G basis set. The optimised allyl fragment has a C2v symmetry. The structure and results summary of the optimized allyl fragment can be seen in the table below.

| Structure | Results summary | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

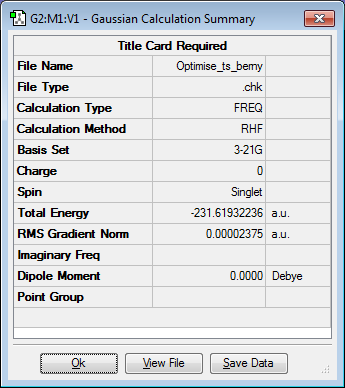

Optimizing the "Chair" transition structure

Optimizing the "Chair" transition structure using the guess transition structure approach

The guess transition structure for the chair transition state was made from two identical copies of the allyl fragment which was previously optimized. The allyl fragments were brought together, with a distance of 2.2 Å between the terminal carbons of each fragment, as this is the distance between the terminal carbons in the transition state. The guess transition structure was then optimized to locate the transition state by using the TS Berny optimization process and a Hartree Fock/3-21G basis set. The results of this optimization are shown in the table below.

| Structure | Results summary | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

The optimised structure was shown to have an imaginary frequency at -817.93 cm-1, this vibration is the one which leads to the Cope rearrangement to occur and confirms that the transition state had been located.This vibration can be seen in the animation below.

Vibration which leads to Cope rearrangement |

Optimizing the "Chair" transition structure using the frozen co-ordinates approach

The chair transition state was located for a second time by the frozen co-ordinates approach. The transition state was confirmed as there was an imaginary vibration at -817.89 cm-1. In the frozen co-ordinate approach, the TS Berny optimisation process and Hartree Fock/3-21G basis set was used. Similarly to the guess transition structure approach,the two allyl fragments were placed at a distance of 2.2 Å between the terminal carbons of each fragment where the bonds/form and break in the Cope rearrangement.However in the frozen co-ordinates approach, the bond distances are fixed at 2.2 Å whilst the rest of the structure becomes optimized. After the initial optimization, the bonds were then optimized separately.The results of the frozen co-ordinate approach are shown below.

| Structure | Results summary | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Vibration which leads to Cope rearrangement |

Comparison of the transition structures obtained from the guess transition structure approach and the frozen co-ordinate approach

The data is summarised in the table below. From the data, it can be seen that the bond lengths for the chair transition state were almost identical for both methods, this shows that both approaches lead to similar transition states.

| Method | Bond Breaking Length (Å) | Bond Forming Length (Å) |

|---|---|---|

| Guess Transition Structure | 1.38928 | 2.02024 |

| Frozen Transition Structure | 1.38930 | 2.02072 |

Optimizing the "Boat" transition structure

In order to optimize the boat transition structure, the QST2 optimization process with a Hartree Fock/3-21G basis set was used. QST2 uses the reactant and product geometry and interpolates between them in order to locate the transition state.A single 1,5-hexadiene conformer can be used for the QST2 process due to the fact that for the Cope rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene, the reactant and product have the same structure with the difference being that the positions of the atoms are different. Initially the anti2 conformer of 1,5-hexadiene was used as both the reactant and product geometries for the QST2 optimization process. Due to the position of the atoms changing between the reactant and the product, it was necessary to label the atoms in order to show how the position of the atoms changed as shown.

| Atom numbering of the reactant | Atom numbering of the product |

|---|---|

|

|

The QST2 optimization failed to find the boat transition state when the anti2 conformer was used as the reactant and product geometry,this was due to the structure of the anti2 conformer not being close enough to the structure of the boat transition state and so a different transition state was found instead, which can be seen in figure 8.

Nf710 (talk) 19:20, 10 February 2016 (UTC) Correct energy and frequencies

Therefore, in order for the QST2 optimization to locate the boat transition state, the structure of the anti2 conformer of 1,5-hexadiene needed to be modified in order to obtain a greater resemblance to the boat transition state. This was done by modifiying the angles of the anti2 conformer. The modified structure of 1,5-hexadiene reactant and product can be seen below.

| Atom numbering of the reactant | Atom numbering of the product |

|---|---|

|

|

The QST2 optimization of these modified structures was successful in locating the boat transition state which was confirmed by the presence of the imaginary frequency at -840.22 cm-1 which is a different imaginary frequency than what was obtained for the chair transition state.This vibration also causes the Cope rearrangement to occur and confirms that the transition state had been located.The results of this optimization and an animation of the vibration can be seen below.

| Structure | Results summary | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Vibration which leads to Cope rearrangement |

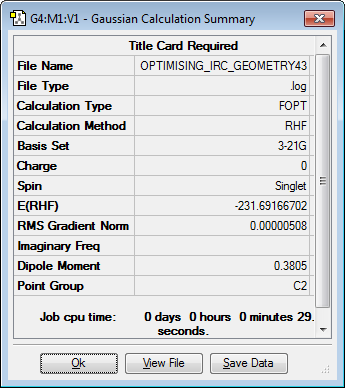

Intrinsic reaction co-ordinate of the "Chair" transition structure

It is generally difficult to predict conformer of the product obtained from a transition structure, however this can be achieved in Gaussview by using the Intrinsic reaction co-ordinate(IRC) calculation. The IRC calculation allows the minimum energy path from a transition state to its local minimum to be seen. IRC method does this by creating a series of points which represent small geometry changes in the direction where the gradient is the steepest. In this computational study, the IRC calculation with a Hartree Fock/3-21G cal basis set was used to find out the conformer of 1,5-hexadiene which was obtained from the chair transition state. As the reaction co-ordinate was symmetrical in this reaction, the reaction co-ordinate was computed only in the forward direction.The results of the IRC calculation can be seen below.

50 sampling points were input in the calculation and this proved sufficient as the calculation had stopped after 44 points. However the stable conformer was unable to be found even though the calculation had converged, this was due to the threshold for the IRC calculation being higher than the threshold of the optimization processes. Therefore, in order to obtain the minimum energy stable conformer, the geometry at the end of the IRC calculation was re-optimized using a minimum optimization process. The re-optimization led to a gauche2 conformer of 1,5-hexadiene, the results of this optimization can be seen in the table below.

Nf710 (talk) 19:21, 10 February 2016 (UTC) Correct conformer found

| Structure | Results summary | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Activation energies

In order to calculate the activation energies for the Cope rearrangement via either transition state, the chair and boat transition needed to be re-optimized by a TS Berny optimization process with a B3LYP/6-31G(d) basis set. Following that, a frequency analysis was computed for the re-optimized structures. Below are the results of the re-optimizations, and animations of the imaginary frequency vibrations for the chair and boat transition states respectively.

| Structure | Results summary | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Vibration at -565.54 cm-1 which leads to Cope rearrangement |

| Structure | Results summary | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Vibration at -530.34 cm-1 which leads to Cope rearrangement |

The activation energy is the difference in energy between the reactant and the transition state. In this case, the anti2 conformer of 1,5-hexadiene was the reactant. Therefore, by looking at the energy difference between the anti2 conformer and the transition states, the activation energy for the different transition states can be calculated. The activation energy can differ based on the basis set and temperature used in the calculation. In this study, the activation energy was found at the Hartree Fock/3-21G and B3LYP/6-31G(d) basis set and at 0 K and 298 K.

| Structure | HF/3-21G Electronic Energy (Hartrees) | HF/3-21G Sum of Electronic and Thermal Energies at 0 K (Hartrees) | HF/3-21G Sum of Electronic and Thermal Energies at 298 K (Hartrees) | B3LYP/6-31G(d) Electronic Energy (Hartrees) | B3LYP/6-31G(d) Sum of Electronic and Thermal Energies at 0 K(Hartrees) | B3LYP/6-31G(d) Sum of Electronic and Thermal Energies at 298 K (Hartrees) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti2 | -231.69253528 | -231.539540 | -231.532566 | -234.61171062 | -234.469219 | -234.461869 |

| Chair | -231.61932233 | -231.466705 | -231.461345 | -234.55698303 | -234.414929 | -234.409009 |

| Boat | -231.60280224 | -231.450930 | -231.445302 | -234.54309307 | -234.402342 | -234.396008 |

From the thermochemical data shown above, the activation energy can calculated from the energy changes. The activation energies are shown in the table below.

| HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G(d) | Expt. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 K | 298.15 K | 0 K | 298.15 K | 0 K | |

| ΔE (Chair)(kcal/mol) | 45.616839 | 44.691890 | 34.067518 | 33.170179 | 33.5 ± 0.5 |

| ΔE (Boat)(kcal/mol) | 55.603661 | 54.759033 | 41.965986 | 41.328436 | 44.7 ± 2.0 |

From this data it can be seen that, even though the geometries of the molecules were quite similar, there was a large difference in the activation energies at a given temperature when using calculations with different basis sets. Also, the B3LYP/6-31G(d) activation energy agrees more closely to the experimental values given. This shows that the lower basis set (Hartree Fock/3-21G) is insufficient in calculating the energy due to not taking into account the exchange correlation.The data also shows that the activation energy is slightly higher at OK than it is at 298K and so less energy is needed to reach the transition state. Lastly, due to the activation energy of the chair transition state being lower than that of the boat transition state, the reaction pathway via the chair transition state is more favoured.

Nf710 (talk) 19:26, 10 February 2016 (UTC) this is a good report, you have done everything asked of you and got the correct energies. you could have gone into more detail about the basis sets but your knowledge of the methods was quite good. well done.

The Diels-Alder cycloaddition

Background

The [4+2] Diels-Alder cycloaddition is a concerted pericyclic reaction in which a molecule with 4 π electrons(diene) approachs a molecule with 2 π electrons (dienophille) causing an interaction between the HOMO of one molecule with the LUMO of another, this results the formation of two new σ bonds. The HOMOs and LUMOs can only interact effectively when they are close in energy and have the same symmetry. This is due to the overlap integral being non zero under these conditions. The reaction is energetically favorable due to the two σ bonds forming being stronger than the two π bonds that break. This reaction is also thermally allowed as there is one π4s component and one π2s component, which follows the rule of (4q+2)s +(4r)a being odd for a reaction to be thermally allowed.The second part of this computational study involves studying the [4+2] Diels-Alder cycloaddition of ethene with cis-1,3 butadiene and maleic anhydride with 1,3 cyclohexadiene. When the dienophiille is substituted, the reaction can occur with endo or exo regiochemistry. The endo and exo regiochemistry will be studied by looking at the reaction of maleic anhydride with 1,3 cyclohexadiene. The reaction scheme for the Diels-Alder cycloaddition reactions which are studied in this computation experiment can be seen in the figures below.

The following calculations used the Semi empirical/AM1 basis set which is effective in carrying out quick calculations, however the energies calculated will be less accurate than the Hartree Fock/3-21G and BY3LP/6-31G(d) basis set.

The Diels-Alder cycloaddition of ethene and cis-1,3-butadiene

Optimizing the ethene and cis-1,3-butadiene reactants

In order to study this Diels-Alder cycloaddition reaction, it was first necessary to build and optimize the ethene and cis-1,3-butadiene molecules. The ethene and 1,3-butadiene molecule were built and then by modifying the dihedral angle of the 1,3-butadiene molecule to 0 degrees, it ensured that the the 1,3-butadiene had a cis conformation. The ethene and cis-1,3-butadiene were then optimized using a minimum optimization process using a Semi empirical/AM1 basis set. The results of the optimization can be seen in the table below.

(Cis-butadiene with a dihedral of 0º is not actually a minimum when calculated with AM1. If you run a frequency calculation you'll find a negative frequency corresponding to the twisting that butadiene undergoes to switch between the two conformers Tam10 (talk) 12:31, 1 February 2016 (UTC))

| Molecule | Structure | Point group | Energy/Hartrees | Results summary | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethene | D2h | 0.02619028 |

| |||

| Cis-1,3-butadiene | C2v | 0.04879719 |

|

Molecular orbitals of the ethylene and cis-1,3-butadiene reactants

After optimizing the reactants, a frequency calculation was done to allow the molecular orbitals, in particular the HOMO and LUMO of the reactants were analysed.

| Molecule | HOMO | Symmetry of HOMO | LUMO | Symmetry of LUMO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethene |

|

Symmetric |

|

Antisymmetric |

| Cis-1,3-butadiene |

|

Antisymmetric |

|

Symmetric |

Optimizing the transition state of the Diels-Alder cycloaddition of ethene and cis-1,3-butadiene

After the ethene and cis-1,3-butadiene reactants were optimized, it was now possible to locate the transition state of the reaction. The transition state was located by using the guess transition structure approach with a TS Berny optimisation process and frequency analysis. Initially, the guess transition structure was built and had a distance of 2.20 Å between the terminal carbons which was the distance used to locate the transition state for the Cope rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene. However this guess structure failed to optimise to the correct transition state and so after trial and error, a distance of 1.95 Å between the terminal carbons of the reactants was found to lead to the correct transition state. This makes sense as, the Cope arrangement is a uni-molecular reaction and so the distance needed between the terminal carbons of the ally fragments does not need to be as close as the distance between the terminal carbons of the reactants for the bi-molecular Diels-Alder reaction. The results of this calculation can be seen below.

| Structure | Energy/Hartrees | Results summary | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.11165476 |

|

| Molecule | HOMO | Symmetry of HOMO | LUMO | Symmetry of LUMO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transition state |

|

Antisymmetric |

|

AntiSymmetric |

(Typo in the table above, but I can see you have the right answer in the paragraph below Tam10 (talk) 12:31, 1 February 2016 (UTC))

Due to the similar energies and complementary symmetry of the LUMO of one reactant and the HOMO of the other reactant, the Diels-Alder cycloaddition was possible. This was shown as the symmetry of the HOMO of cis-1,3-butadiene and the LUMO of ethene were both symmetric, and so they were able to overlap effectively to form the symmetric LUMO of the transition state. This was also seen in the case of the HOMO of ethene and LUMO of cis-1,3-butadiene, as they were both antisymmetric, they were able to overlap to form the antisymmetric HOMO of the transition state. This was confirmed to be the transition state as there was a imaginary vibration at -956.13 cm-1. The animation below shows that the terminal carbons of each fragment move towards each other in sync, this confirms that the reaction is concerted as the two new C-C bonds form at the same time. In contrast, the lowest positive vibration at 147.24 cm-1 does not lead to the Diels-Alder cycloaddition, this can be seen from the animation below as the terminal carbons have a sideways motion which does not contribute to bond formation/breaking process.

(You have the TS HOMO/LUMO the wrong way around Tam10 (talk) 12:31, 1 February 2016 (UTC))

Vibration which leads to the Diels-Alder cycloaddition |

Lowest positive frequency vibration which does not lead to the Diels-Alder cycloaddition |

Analysis of the geometry of the transition structure from the Diels-Alder cycloaddition of ethene and cis-butadiene

The presence of the imaginary frequency at -956.13 cm-1 confirmed that the structure was a transition state. To obtain further evidence that this specific transition state was the transition state of the Diels-Alder cycloaddition, the C-C bond lengths and van der Waals radius of the relevant carbon atoms involved in the formation of the new σ bond were analysed. This data can be seen in the table below, and the the atoms are labelled according to the image shown in figure 10.

| Atoms | Bond lengths (Å) |

|---|---|

| C1-C2 | 1.38183 |

| C2-C3 | 1.39744 |

| C3-C4 | 1.38189 |

| C4-C5 | 2.119606 |

| C5-C6 | 1.38289 |

| C1-C6 | 2.11960 |

In this reaction, the double bonds between C1-C2,C3-C4 and C5-C6 were being broken whilst two new single bonds were forming between C4-C5 and C1-C6. This is proven in the data as the C1-C2,C3-C4 and C5-C6 bond lengths were slightly longer than the bond length of a typical sp2 hybridised carbon atom which is 1.34 Å but still shorter than bond length of a typical sp3 hybridised carbon atom which is 1.54 Å[5]. The C4-C5 and C1-C6 bond forming lengths were shorter than twice the van der waal radii of a carbon atom,1.70Å[6], which shows that a bonding interaction was taking place between the terminal carbons which suggests that new σ bonds were forming.

The Diels-Alder cycloaddition of maleic anhydride and 1,3-cyclohexadiene

When the dienophille in the Diels-Alder reaction is substituted, the reaction can result in two regiochemically distinct products, the exo and endo products. In this study,the regioselectivty of the Diels-Alder cycloaddition between maleic anhydride and 1,3-cyclohexadiene will be examined by looking at the which transition structure was lower in energy,the endo or the exo, and thus which transition state was more favoured. The following calculations used the Semi empirical/AM1 basis set.

Optimizing maleic anhydride and 1,3-cyclohexadiene reactants

In order to study this Diels-Alder cycloaddition reaction, it was first necessary to build the maleic anhydride and 1,3-cyclohexadiene molecules.The maleic anhydride and 1,3-cyclohexadiene were then optimized using a minimum optimization process, the results of the optimization can be seen in the table below.

| Molecule | Structure | Point group | Energy/Hartrees | Results summary | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maleic anhydride | C2v | -0.12182418 |

| |||

| 1,3-Cyclohexadiene | C2v | 0.02771153 |

|

Molecular orbitals of maleic anhydride and 1,3-cyclohexadiene reactants

After the optimizing the reactants, a frequency calculation was done to allow the molecular orbitals, in particular the HOMO and LUMO of the reactants were to be analysed once again.

| Molecule | HOMO | Symmetry of HOMO | LUMO | Symmetry of LUMO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maleic anhydride |

|

Symmetric |

|

Antisymmetric |

| 1,3-Cyclohexadiene |

|

Antisymmetric |

|

Symmetric |

Optimizing the endo transition state of maleic anhydride and 1,3-cyclohexadiene

After the maleic anhydride and 1,3-cyclohexadiene were optimized. It was now possible to locate the transition state of the reaction.The transition state for this reaction was located using the same optimization process, basis set and approach as the previous Diels-Alder reaction between ethene and cis-1,3 butadiene, in which a guess transition structure was made and a distance of 1.95 Å was used as the distance between the terminal carbons of the reactants. However, to ensure that the endo product was formed, the maleic anhydride and 1,3-cyclohexadiene had to approach each other in an endo conformation such that secondary orbital interactions were possible. The results of this calculation can be seen in the table below.

| Structure | Energy/Hartrees | Results summary | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| -0.05150478 |

|

| Molecule | HOMO | Symmetry of HOMO | LUMO | Symmetry of LUMO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transition state |

|

Antisymmetric |

|

Antisymmetric |

Once again, due to the similar energies and complementary symmetry of the LUMO of one reactant and the HOMO of the other reactant, the Diels-Alder cycloaddition was possible. The Diels-Alder transition state was confirmed by the presence of a imaginary vibration at -806.34 cm-1. The animation for this vibration can be seen below and it shows that the bonds are formed in a concerted fashion as the terminal carbons of both reactant move towards each other in sync.

Vibration which leads to the Diels-Alder cycloaddition |

Optimizing the exo transition state of maleic anhydride and 1,3-cyclohexadiene

The transition state for the exo transition state was found in the same way as the endo transition state, however to ensure that the exo product was formed, the maleic anhydride and 1,3 cyclohexadiene had to approach each other in a exo conformation instead of an endo conformation. The results of the calculation used to find the exo transition state can be seen in the table below.

| Structure | Energy/Hartrees | Results summary | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| -0.05041980 |

|

| Molecule | HOMO | Symmetry of HOMO | LUMO | Symmetry of LUMO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transition state |

|

Antisymmetric |

|

Antisymmetric |

The Diels-Alder transition state was confirmed by the presence of a imaginary vibration at -812.25 cm-1. The animation for this vibration can be seen below and it shows that the bonds are formed in a concerted fashion similar to the previous Diels-Alder reactions.

Vibration which leads to the Diels-Alder cycloaddition |

Alternative way of optimizing the endo and exo transition state of maleic anhydride and 1,3-cyclohexadiene

An alternative method of optimizing the endo transition states was by performing a TS Berny optimization process on the endo product which was modified to resemble the endo transition state. The endo product was modified by lengthening the bonds that break/form in the Diels-Alder cycloaddition. This method of optimizing the product instead of the reactants was effective due to the product being a bicyclic system, therefore the structure was more conformationally rigid than the reactants. Due to this conformational rigidity of the endo product, it was easier to reach the endo transition state rather than another transition state such as the exo transition state. The exo transition state was optimized from the exo product in an identical way. Due to the greater conformational rigidity of the exo product, it was easier to reach the exo transition state rather than the endo transition state.

Comparison of the endo and exo transition states

Having now optimised both the endo and exo transition state, the favored transition state can be found by comparing the energies and the geometry of the two transition states.

Energies of the endo and exo transition state

| AM1 Semi-Empirical | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic energy (Hartrees) | Sum of electronic and zero-point energies (Hartrees) | Sum of electronic and thermal energies (Hartrees) | |

| at 0 K | at 298 K | ||

| Exo TS | -0.05041980 | 0.134880 | 0.144880 |

| Endo TS | -0.05150478 | 0.133494 | 0.143683 |

| Cyclohexa-1,3-diene | 0.02771153 | 0.152502 | 0.157726 |

| Maleic anhydride | -0.12182418 | -0.058192 | -0.057248 |

The activation energy was found from the difference in energy of transition state and the sum of the energy of the reactants. Below, the summary of the activation energies are provided.

| AM1 Semi-Empirical | AM1 Semi-Empirical | |

| at 0 K | at 298 K | |

| ΔE (Exo TS) (kcal/mol) | 25.458081 | 24.588352 |

| ΔE (Endo TS) (kcal/mol) | 27.862699 | 27.111570 |

(Activation energies also the wrong way around! Tam10 (talk) 12:31, 1 February 2016 (UTC))

From the activation energies in the table, it can be seen that the activation energy for the endo transition state is lower in energy and so the Diels-Alder between maleic anhydride and cyclohexa-1,3-diene takes place via an endo transition state.

Geometries of the endo and exo transition state

The bond lengths of the atoms shown in the tables below correspond to atoms labelled in the diagram of the endo and exo transition state.

| Atom numbering of the Endo transition state | Atom numbering of the Exo transition state |

|---|---|

|

|

For the endo transition state:

| Atoms | Bond lengths (Å) |

|---|---|

| C1-C2 | 1.39717 |

| C2-C3 | 1.39304 |

| C3-C4 | 1.49053 |

| C3-C8 | 2.16238 |

| C7-C8 | 1.40849 |

| C8-C9 | 1.48924 |

For the exo transition state:

| Atoms | Bond lengths (Å) |

|---|---|

| C1-C2 | 1.39677 |

| C2-C3 | 1.39440 |

| C3-C4 | 1.48974 |

| C3-C8 | 2.17044 |

| C7-C8 | 1.41009 |

| C8-C9 | 1.48825 |

Even though there is a high level of error in Gaussview, the bond lengths can still be compared up to 2 decimal places. From the data above it can be seen that the bond length between C3-C8 is shorter than twice the van der waal radii of the carbon atom, 1.70 Å[6], for both the exo and endo transition states and so this confirms that a new σ formed is being formed. To obtain an understanding of the energy difference of the endo and exo transition states, the geometry and the nodal properties of the HOMO were analysed. It can be seen that there are more nodes present between the -(C=O)-O-(C=O)- and the remainder of the fragment in the endo transition structure than the exo transition structure which would indicate that the endo transition state is higher in energy than the exo transition state. However the endo transition state is more stable than the exo transition state, this is due to the greater steric hindrance from the side groups in the exo TS being shorter than twice the van der waal radii. This steric clash in the exo transition state prevents the different orbitals of the different fragments coming close together and interacting favorably. As a result of this, the C3-C8 bond length is slightly shorter in the case of the endo transition state (2.16 Å) compared to the exo transition state (2.17 Å) and this allows greater bonding interaction between the fragments in the endo transition state. which results in the endo transition state being more favoured. Additionally, the endo transition is further lowered in energy than the exo transition state due to endo transition state having stabilizing interactions through the overlap of the π orbitals of the 1,3-cyclohexadiene and the π* orbitals of the carbonyl groups on the maleic anhydride which lowers the energy of the endo transition state and allows it to be kinetically preferred. This interaction is known as the secondary orbital effect and it is not possible in the exo transition state, as the carbonyls of the maleic anhydride are too far away to interact with the π orbitals of the double bonds on 1,3-cyclohexadiene however as a result of this, there is less steric hinderance in the exo product which allows it to be the thermodynamically preferred product.

(Are you able to demonstrate this secondary orbital overlap? The error in bond distances primary comes from the method you're using Tam10 (talk) 12:31, 1 February 2016 (UTC))

Conclusion

Overall, the Cope rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene and the Diels-Alder cycloadditions of ethene with cis-1,3 butadiene and maleic anhydride and 1,3-cyclohexadiene were studied in the computational experiment.

For the analysis of the Cope rearrangement, 3 different optimization processes were used with two different basis sets, Hartree Fock/3-21G and B3YLP/6-31G. The results at different basis sets were compared and both basis sets calculated appropriate geometries for the different conformers and the transition states, however the B3LYP/6-31G basis was more accurate in calculating energies than the Hartree Fock/3-21G basis. This was due to the B3LYP/6-31G basis set taking into account the exchange correlation whereas the HF/3-21G does not. The chair transition structures were made by the guess transition structure and the frozen co-ordinate approach, whilst the boat was made by the QST2 optimization process. The transition states were confirmed by the presence of different imaginary frequencies and it was found out that the chair transition state was more favored which was proven by the lower activation energy of the chair transition state.

By studying the Diels-Alder cycloaddition of ethene and cis-1,3-butadiene, it proved that both σ bonds were formed in a concerted way as the vibration showed that the terminal carbons of the reactants were moving towards each other in sync. The Diels-Alder cycloaddition of maleic anhydride and 1,3-cyclohexadiene were studied in order to obtain a greater understanding of the regioselectivity of endo and exo products. By analysing the molecular orbitals and geometry of the transition state, it was seen that the endo transition state had a lower activation energy due to having less steric strain and the presence of a secondary orbital effect.

In order to obtain a greater understanding of pericyclic reactions, there are numerous different reactions which could have been computed. In order to have a greater understanding of the Cope rearrangment, one could have used a asymmetric reactant for the Cope rearrangement which would result in a different isomeric product to form, or potentially a diene that goes through a different transition state. Further research could have been on studying cycloaddition reactions such as looking at a [3+2] cycloaddition reactions or inverse electron demand cycloadditions.

References

- ↑ .A. Day, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1975, 97, 2431-2438

- ↑ O. Wiest, K. Black and K. Houk, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1994, 116, 10336-10337

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 B. Gung, Z. Zhu and R. Fouch, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1995, 117, 1783-1788

- ↑ G. Schultz, I. Hargittai, J. Mol. Struct., 1995, 346, pp 63-69

- ↑ R. J. Ouellette, J. David Rawn, Organic Chemistry Structure, Mechanism, and Synthesis, Elseview Inc., USA, 1st Ed., 2014, p 27

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 R. S. Rowland, R. Taylor, J. Phys. Chem., 1996, 100(18), 7384-7391