Rep:Mod:NF1C

Hydrogenation of Cyclopentadiene dimers

Cyclopentadiene dimerises spontaneously at room temperature[1] via a Diels-Alder reaction (π4s + π2s cycloaddition). Unless thermodynamic conditions are applied, the endo adduct is favoured over the more stable exo one. This is because not only the bond forming orbitals in the HOMO or LUMO of the diene or dienophile respectively have the right symmetry but the rest of the orbitals also yield favourable bonding interactions. Therefore the endo dimer is preferred i.e. formed faster, it is the kinetic product.[2] The computational energy evaluation of each isomer should confirm this.

Exo-cyclopentadiene dimer 1

In fact the exo dimer 1 has a lower total energy than the endo equivalent. This proving the point made above: 1 is the more stable thermodynamic and 2 is the kinetic product. However, the actual difference is rather small.

Comparing each individual total energy it can be seen that the angle bending energy has the highest contribution to this difference followed by the electrostatic energy.

The same way the two hydrogenated dihydro derivatives can be compared. 3 has a higher total energy than 4 thus it must the kinetic product while 4 will be the thermosdynamic one. So it can be assumed that specifically the hydrogenated product 3 is formed if no thermodynamic conditions are applied.

| Bond | Product 3 | Product 4 |

|---|---|---|

| C=C-C | 107.4° | 112.0° |

| C=C-H | 126.7° | 123.5° |

| C-C-C | 125.9° | 124.5° |

| Sum: | 360° | 360° |

This time the van der Waals energies and mainly the total angle bending energy account for the much larger difference between 1 and 2. The much larger angle bending energy of 3 is likely to be due to the C=C double bond. The following data was obtained from Avogadro focussing on one C-atom involved in the double bond: The optimum angles for a sp2 hybridised carbon is 120°. Thus clearly the CCC angle type is far from this value and thus imposes especially in product 3 a lot of strain increasing the angle bending energy by a lot.

These two compounds (9 & 10) are intermediates in the synthesis of Taxol. The initial synthesis was suggested with the carbonyl pointing either up or down.[3] Since 9 and 10 are formed via a reversible oxy-Cope rearrangement, eiher both isomers are present or formed when one of them is left standing. In the following evaluation the relative stability of both atropisomers is determined by looking at their total energies.

It was also found that the isomer-selectivity highly depends upon substituents on the 6-membered ring. This cyclohexane is fused to a larger ring and can of course adopt its usual conformers that are shown in the diagram[2]. on the right. Consequently, the most important conformers of each 9 and 10 have been looked at in more detail and will be compared below.

Atropisomer 9 of Taxol

As expected (one of) the chair conformation (1) is the one with the lowest energy followed by (one of) the twist boat (1). They differ in energy mostly due to some angle bending, van der Waal and torsional energy. The boat conformation is the highest in energy of these three as predicted by the diagram. Relative to twist boat 1 this is due to the van der Waals and torsional energy, of which latter seems plausible when considering the H-atoms on the 1 and 4 positions of the ring i.e. those attached to the carbon atoms up-bending out of the plane.

Perhaps surprising is, however, that both the other two other conformations i.e chair 2 and twist boat 2 respectively are so much higher in energy than their name equivalents, even though they are shown to be the same in the diagram. However, it is dealt with substituted cyclohexane rings, which is why the diagram obviously does not apply anymore.

Compared to their name equivalents chair 2 and twist boat 2 have a higher angle bending, a torsional and van der Waal energy.

Atropisomer 10 of Taxol

For atropisomer 10 the chair 1 conformation has also the lowest energy, followed by the twist boat 1 and then the boat conformations. Again the first two differ in energy due to angle bending, van der Waal and torsional energy, which also cause the difference between each the two chair and twist boat name equivalents.

The alkene functional group in both 9 and 10 reacts extremely slowly because alkene reactions involve the build-up of partial positive charge on the passive alkene-carbon. This intermediate carbocation could be imagined to be stabilised by hyperconjugation quite well as a tertiary cation could be formed. However, the carbocation is sp2 hybridised and thus should be planar, which is not possible in a cage structure like this. The carbocation would have to be tetrahedral instead resulting in a very unfavourable process. Ergo the slow rate.

For comparison both the intermediates 17 and 18 have been investigated. The total energy of 17 is higher than that of 18 mainly due to the van der Waals, the angle bending and the torsional energies. This difference is large because the values given out by the program were given in Hartrees. Converted to kJ/mol the difference in energy between 17 and 18 is ~5.4 kJ/mol. Considering that room temperature is of an energy of kBT = 1.38x10-23 J K-1 mol-1 x 298 K = 4.11 x 10-24 kJ/mol it becomes obvious that the two isomeric forms are not easily interconvertable.

| Isomer | free energy ΔG (Hartrees) | free energy ΔG (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| 17 | -1651.463260 | -4335917.119423 |

| 18 | -1651.461191 | -4335911.687263 |

| Difference (18-17) | 0.002069 | 5.43216 |

| Computational results | Literature results[4] 300 MHz | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Integration | Chemical Shift (δ) | Chemical Shift (δ) | Integration |

| 1 H | 5.15 | 4.84 | 1 H |

| 3 H | 3.31-3.16 | 3.40-3.10 | 4 H |

| 2 H | 3.01 | 2.99 | 1 H |

| 14 H | 2.72-1.75 | 2.80-1.35 | 14 H |

| 3 H | 1.60 | 1.38 | 3 H |

| 2 H | 1.49-1.16 | 1.25 | 3 H |

| 3 H | 0.91 | 1.10 | 3 H |

| 2 H | 0.82-0.59 | 1.00-0.80 | 1 H |

| 30 H | 30 H | ||

| Computational results | Literature results[4] 75 MHz | |

|---|---|---|

| C nr. | Chemical Shift (ppm) | Chemical Shift (ppm) |

| 1 | 216.10 | 218.79 |

| 2 | 145.13 | 144.63 |

| 3 | 124.69 | 125.33 |

| 4 | 90.65 | 72.88 |

| 5 | 60.64 | 56.19 |

| 6 | 57.05 | 52.52 |

| 7 | 52.48 | 48.50 |

| 8 | 51.55 | 46.80 |

| 9 | 46.69 | 45.76 |

| 10 | 45.95 | 39.80 |

| 11 | 42.18 | 38.81 |

| 12 | 40.58 | 35.85 |

| 13 | 35.32 | 32.66 |

| 14 | 31.01 | 28.79 |

| 15 | 29.34 | 28.29 |

| 16 | 29.34 | 26.88 |

| 17 | 27.09 | 25.66 |

| 18 | 26.40 | 23.86 |

| 19 | 22.90 | 20.96 |

| 20 | 19.73 | 18.71 |

This is the Dspace-URL for the NMR calculation of 17.

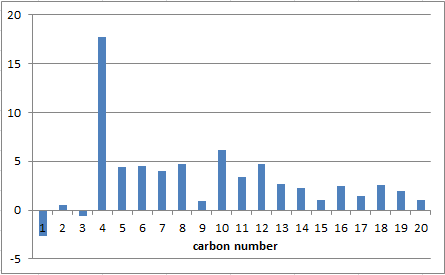

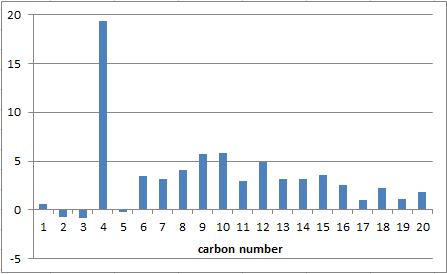

The chemical shifts and integration results obtained from computational calculations do compare quite well with the ones found experimentally in the literature both in 1H and 13C NMR.

There are some variations in 1H NMR as for example the most deshielded hydrogen that was listed to be at 4.84 in the literature but is even 5.15 in the computational results. Also the integrations do not always fit perfectly.

Similar differences can be found in the 13C NMR, of which the greatest is the predicted shift at 90.65 ppm that corresponds to the experimentally found one at 72.88 ppm. This is almost a difference of 20 ppm and thus could be interpreted to be due to a different functional group than it actually is. Ergo it is a significant error source that could mislead to the wrong interpretation of NMR spectra.

However, overall credit must be given to the computational analysis, which can predict NMR spectra very accurately for that matter and thus can be considered as a useful and competent tool.

| Computational results | Literature results[4] 300 MHz | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Integration | Chemical Shift (δ) | Chemical Shift (δ) | Integration |

| 1 H | 5.98 | 5.21 | 1 H |

| 7 H | 3.20-2.78 | 3.00-2.70 | 6 H |

| 4 H | 2.66-2.48 | 2.70-2.35 | 4 H |

| 6 H | 2.33-1.84 | 2.20-1.70 | 6 H |

| 1.58 | 1 H | ||

| 4 H | 1.58 | 1.50-1.20 | 3 H |

| 3 H | 1.28 | 1.10 | 3 H |

| 1 H | 1.21 | 1.07 | 3 H |

| 4 H | 0.96-0.64 | 1.03 | 3 H |

| 30 H | 30 H | ||

| Computational results | Literature results[4] 75 MHz | |

|---|---|---|

| C nr. | Chemical Shift (ppm) | Chemical Shift (ppm) |

| 1 | 212.12 | 211.49 |

| 2 | 147.97 | 148.72 |

| 3 | 120.03 | 120.90 |

| 4 | 94.01 | 74.61 |

| 5 | 60.32 | 60.53 |

| 6 | 54.77 | 51.30 |

| 7 | 54.09 | 50.94 |

| 8 | 49.58 | 45.53 |

| 9 | 49.0 | 43.28 |

| 10 | 46.67 | 40.82 |

| 11 | 41.69 | 38.73 |

| 12 | 41.69 | 36.78 |

| 13 | 38.63 | 35.47 |

| 14 | 34.03 | 30.84 |

| 15 | 33.54 | 30.00 |

| 16 | 28.05 | 25.56 |

| 17 | 26.36 | 25.35 |

| 18 | 24.43 | 22.21 |

| 19 | 22.51 | 21.39 |

| 20 | 21.61 | 19.83 |

This is the Dspace-URL for the NMR calculation of 18.

Again the computed NMR values compare quite well to the ones given in the literature and once again the greatest deviations is from carbon number 4 where 94.01 ppm has been obtained via computational analysis but 74.61 ppm was experimentally determined.

The NMRs of 17 and 18 have all compared fairly well to the literature. Except for some variations in theit 1H NMRs the computed NMRs look very similar, too. Noticeable is a similar deviation pattern from literature and the same large deviation of carbon 4. Some contribution to this shift can be given to the TMS error that occurs because the program calculates the NMR using TMS as the solvent. However, nowadays TMS is not used anymore, thus the error.

Epoxidation of two alkenes using Shi' catalyst and Jacobsen's catalyst

The crystal structures of Shi's catalyst

| Atom labels | C-O distances (nm) |

|---|---|

| O1-C1 | 0.140 |

| O1-C7 | 0.141 |

| O2-C2 | 0.140 |

| O2-C7 | 0.144 |

| O4-C4 | 0.139 |

| O4-C10 | 0.144 |

| O5-C5 | 0.142 |

| O5-C10 | 0.141 |

| O6-C2 | 0.140 |

| O6-C6 | 0.142 |

The lengths of the individual C-O bonds varies in Shi's catalyst according to the Cambridge crystal database data as shown in the table. Only one anomeric centre as such is present in the molecule (the ether group in the 6-membered ring). This can donate electron density into the C-O σ* orbital. This overlap is only possible if this C-X acceptor group is in the axial position. This stabilisation makes the axial position favourable, which is in fact the case in this structure.

However, whether officially anomeric centre or not - all of the ether oxygens are capable of donating their lone pairs into the C-C σ* orbital. For this to happen again an antiperiplanar configuration must be present as just described.

This donation strengthens the C-O bond and thus shortens it while the C-C bond is weakened and lengthened. This can be observed very nicely by comparing the O4-C4 bond with the O4-C10 with 0.139 and 0.144 nm respectively. The O4-C10 is longer because no bond with correct arrangement for overlap is available. Thus the O4-C4 bond should be more described as becoming shorter due to a suitable orbital overlap with the C4-C5 σ* orbital. As a result the C4-C5 bond distance is longer than eg the C10-C11 one.

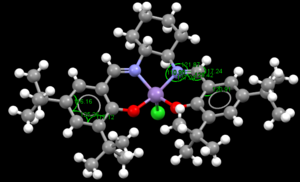

The crystal structures of Jacobsen's catalyst

|

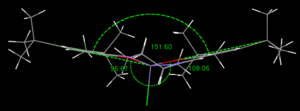

Jacobsen's catalyst has also been analysed. In the catalyst the conjugated system is extended by the imine bond and resonance can also be drawn with oxygen's lone pairs. Therefore this molecule is highly planar on both sides of the Mn-ion. Only the coordination to the metal and the connecting cyclohexane ring as well as the t-butyl substituents allow rotation. The repulsion of the axial chloride can be seen clearly by the distortion of a square planar structure as seen nicely in the picture on the left. Different forms have already been investigated and this particular one is recorded as 'bowl-shaped'.[5]

Furthermore of course the t-butyl substituents on the phenol rings exhibit strong steric repulsion. The t-butyls on the 3-position of the 3,5-di-tert-butylsalicylidene push each other apart, which the small H76-H53 distance of 0.168 nm compared to the H53-H81 one of 0.223 nm is evidence as they should have been of the same length if no repulsion would be observed. 0.168 nm clearly is a repulsive interaction as the van der Waals radius of H in a H...H interaction is 1.2 Å[6] and thus anything below 0.210 nm becomes repulsive and only above 0.24 nm is attractive.[7].

| bond | bond distance (nm) |

|---|---|

| H87-H67 | 0.207 |

| H88-H93 | 0.226 |

| H95-H92 | 0.214 |

| H92-H68 | 0.244 |

| H68-H98 | 0.181 |

| H97-H100 | 0.227 |

| H99-H72 | 0.208 |

| H74-H75 | 0.196 |

| H71-H77 | 0.216 |

| H76-H53 | 0.168 |

| H53-H81 | 0.223 |

| H83-H85 | 0.206 |

| H84-H54 | 0.216 |

The same is seen on the other side with 0.181 nm (H68-H98) relative to 0.244 nm (H92-H68). Consequently the t-butyl groups on the 5-position are pushed further outwards also leading to slightly repulsive interactions of 0.207 nm (H87-H67) and 0.216 nm (H84-H54).

Interesting is also to see that even protons within these bulky substituents exhibit repulsive interactions as for example the H74-H75 bond with 0.196 nm. Therefore overall little attractive interactions are observed in Jacobsen's catalyst on or at the t-butyl groups.

Another repulsive interaction is present between the coordinated oxygens and the imine group on either side. Proof for this are the angles of the sp2 hybridised carbon or nitrogen of the imine. While the angles facing the oxygen, 127° and 125° are larger than 120° as the substituents try to spread apart, others (110° and 117°) have to compensate for this.

1H and 13C NMR of styrene and trans-stilbene

| Computational results | Literature results[8] 400 MHz | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Integration | Chemical Shift (δ) | Chemical Shift (δ) | Integration |

| 5 H | 7.49-7.30 | 7.38-7.26 | 5 H |

| 1 H | 3.66 | 3.88-3.85 | 1 H |

| 1 H | 3.12 | 3.16-3.14 | 1 H |

| 1 H | 2.54 | 2.79-2.82 | 1 H |

| 8 H | 8 H | ||

This is the Dspace-URL for the NMR calculation of styrene oxide.

This is the Dspace-URL for the NMR calculation of styrene oxide.

| Computational results | Literature results[9] 300 MHz | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Integration | Chemical Shift (δ) | Chemical Shift (δ) | Integration |

| 10 H | 7.57-7.48 | 7.42-7.32 | 10 H |

| 2 H | 3.54 | 3.87 | 2 H |

| 12 H | 12 H | ||

This is the Dspace-URL for the NMR calculation of stilbene oxide.

This is the Dspace-URL for the NMR calculation of stilbene oxide.

As for taxol the computed NMRs compare very well to the literature. There are some deviationsas last time but this might (at least partially) be due to the TMS error described above. Therefore overall again a nice demonstration of the potential of computational chemistry.

Assigning the absolute configuration of styrene and trans-stilbene via the optical rotation

| enantiomer | computed value [α]D | literature value [α]D |

|---|---|---|

| (R)-(+)-styrene oxide | -30.44° (Dspace-URL) | -23°[10] |

| (S)-(-)-styrene oxide | 30.44° (Dspace-URL) | 32.1°[11] |

| (+)-(R,R)-trans-stilbene oxide | 298.32° (Dspace-URL) | 250.8°[12] |

| (-)-(S,S)-trans-stilbene oxide | -297.82° (Dspace-URL) | -249°[13] |

The computed values are slightly different to the ones from literature. Also the literature values themselves vary quite widely highlighting the experimental unreliability of determining optical rotations. Solvents seem to influence these values strongly, too.

Therefore once again computational chemistry proves its usefulness because in theory all calculations should result in approximately the same same values. The outcome is based on calculations only and cannot easily be compared to one another without any changes from the environment such as temperature, pressure or solvent impurity.

Enantiomeric excess calculation of stilbene oxide using Shi's catalyst

For the following three sections the epoxidation of stilbene using Shi's catalyst has been chosen as an example. To understand the discussions of the following methods, the mechanism for the epoxidation is presented.

Shi et al. suggested the reaction scheme on the right where the peroxymonosulfate anion adds across the carbonyl bond followed by the formation of a 3-membered peracid ring. The alkene substrate abstracts the added oxygen to form an epoxide and regenerate the ketone.

trans-stilbene oxide has two chiral centres. The question thus is which diastereomer will be formed. The left table compares the energies of all transition states for each diastereomer and the right one calculates the enantiomeric excess.

| nr. | R,R series | S,S series |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | -1535.14760552 | -1535.14668122 |

| 2 | -1535.14902029 | -1535.14601044 |

| 3 | -1535.16270178 | -1535.15629511 |

| 4 | -1535.16270154 | -1535.15243112 |

| R,R 3 | S,S 3 | |

|---|---|---|

| Free energy (Hartree) | -1535.16270178 | -1535.15629511 |

| Free energy (kJ mol-1) | -4030569.98 | -4030553.16 |

| Energy difference (kJ mol-1) (R,R 3 - S,S 3) |

16.82 | |

| K | 848.65 | |

| Enantiomeric excess | 0.99882 | |

| Percentage | 99.9% (lit. 98.9%[14]) | |

The calculations using the free energies that the epoxidation of the third transition state of stilbene from the R,R series is in a huge enantiomeric excess with 99.9% over its diastereoisomeric equivalent of the S,S series. This seems reasonable considering that the mentioned transition state from the R,R series is the one with the lowest energy of all eight.

Perhaps, more interesting than the epoxidation mechanism illustrated above, however, is the reason behind the different energetic transition states and the thus strongly favoured formation of R,R-stilbene oxide over the S,S-diastereomer. This is demonstrated in the above picture on the right.

There are two approaches of the alkene onto the catalyst: via the spiro or the planar form shown on the right. Due to steric hindrance transition states 2 and 3 are disfavoured. Both spiro or the planar approach 1 and 4 do not have this steric effect and are therefore favoured. Transition state 1 would lead to the R,R diastereomer while 4 results in the S,S one. It is believed by Shi et al. that the spiro approach is favoured over the planar one due to a stabilising overlap of the oxygen lone pair from the 3-membered ring with the π*-orbitals of the alkene.[14]

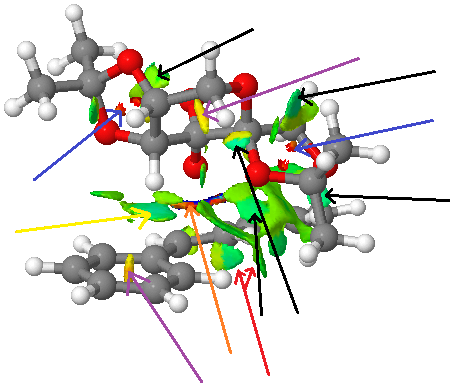

Investigating the non-covalent interactions in the active-site of the reaction transition state

|

In this section the non-covalent interactions in the reaction transition state of the epoxidation of (R,R)-tans-stilbene[15] using Shi's catalyst is illustrated and described. For this the transition state of the trans-stilbene enantiomers with the lowest energy has been chosen.

For reference the meaning of the colours and arrows are listed in the table on the right. Clearly, most interactions between the catalyst and the reacting substrate are (weakly) attractive, which holds the the two molecules together. Several types of interactions have been pointed out with the differently coloured arrows.

Since Shi's catalyst contains in its active form so many oxygens several hydrogen bond-like interactions can be observed (black arrow) been O and some hydrogens of the substrate. These are - ignoring the site of epoxidation - the strongest attractive interactions between the molecules and is coloured green-blue.

| blue | very attractive |

| green | mildly attractive |

| yellow | mildly repulsive |

| red | strongly repulsive |

| black arrow | H-bonding-like (H...O) |

| blue arrow | steric O...O + ring repulsion |

| purple arrow | steric ring repulsion |

| yellow arrow | H-bonding-like (H...aromatic ring) |

| red arrow | H...H intraction |

| orange arrow | site of bond forming |

A similar strongly attractive interaction is between the hydrogen attached to the α-carbon of one of the ether groups and the centre of one of the aromatic ring. It was found that aromatic rings such as benzene can act as a hydrogen bond acceptor forming a bond of half its usual strength.[16] Of course, no strong hydrogen bond donor is present in any of the two just described interactions, which is why these interactions do not exhibit real H-bond strengths. But they are still quite attractive.

The red arrow represents an example of an H...H type interaction that is quite attractive and is results due to two hydrogen atoms approaching each other close in space.

Both the blue and the purple arrow represent repulsive interactions that arise because the atoms are fused to a ring and thus their movement is strained. Steric repulsion is therefore not avoidable. The 6-membered rings only show mildly repulsive interactions despite the presence of an electronegative oxygen in the ring in Shi's catalyst. Consequently, the 5-membered ring has strongly repulsive interactions, firstly due to a 5-membered ring being smaller and secondly because two oxygen atoms are present.

Concluding, the computation of the NCI (non-covalent interactions) appears to be a highly interesting and useful tool to picture the inter-molecular interactions between to molecules. Especially the illustration of a transition state in a catalysed reaction like this one opens up new possibilities. Not as many information can be found by experimentational methods about transition states as precise as computational chemistry does.

Investigating the Electronic topology (QTAIM) in the active-site of the reaction transition state

| purple ball | electron density maximum |

| yellow ball | electron density minimum |

| yellow arrow | C-C BCP (covalent) |

| orange arrow | C-H BCP (covalent) |

| brown arrow | C-O BCP (covalent) |

| white arrow | H...O BCP (non-covalent) |

| blue arrow | H...H BCP (non-covalent) |

| green arrow | H...C BCP or H...aromatic ring BCP (non-covalent) |

| red arrow | bond forming BCP (half covalent) |

The reaction transition state under investigation is the same as for the NCI method: Epoxidation of (R,R)-trans-stilbene using Shi's catalyst. The QTAIM method illustrates the electron density within molecules essentially resembling the electronic structure and thus providing more understanding in its reactivity.[17] The purple and yellow balls generated by the program represent electron density mini- or maxima. Thus the purple balls are positioned at the location of atoms and the spots where the first derivative of the electron density with respect to all three coordinates become 0 is replaced by the yellow balls are defined by the spot. The latter are called the bond topological critical points (BCPs) and should always be present between the pathway of interactions of two nuclei.[18] The computation of several such covalent as well as non-covalent interactions will be pointed out.

The yellow arrow shows an example of a covalent interaction between two carbon atoms such as the aromatic ones. Obviously the electron density minimum sits right in the middle between them as it is the same carbons in the same environment. The orange and brown arrows, however, indicate covalent interactions between two different nuclei each. The contribution to the shared electron density of these interactions, C-H (8:2) and C-O (3:7) respectively, is in the order O > C > H as would be expected.

The white arrow points out the H-bonding-like, H...O interactions (black arrows in the NCI section above). By eye the contribution to the electron density can be estimated to be of about 65% by oxygen.

There are also a few H...H - both inter- and intramolecular - interactions corresponding to the blue arrow. Each H has essentially a contribution of 50%, however it looks like the hydrogens of Shi's catalyst contribute more electron density to the intermolecular examples.

Finally the green arrows indicate the interaction that has been demonstrated by the yellow arrow above: the H...aromatic ring hydrogen bond-like attraction. However, unlike previously mentioned only one carbon atom of the aromatic ring seems to interact with the corresponding hydrogen in a 6:4 fashion respectively.

The red arrow points out the bond forming transition state with almost 5:5 contributions of electron density. But as above this one is neglecting for further investigation.

As the NCI, the QTAIM method is a powerful tool to illustrate the relevant electronic topology within molecules as well as transition states as this particular one. Relative to the NCI it gives a more detailed idea of the exact electron density of an interaction between two nuclei including covalent bonds which are neglected in the NCI. However, the QTAIM does not give many information about the strength of attraction of any interaction.

Suggesting new candidates for investigations

Aim of this part was to find an epoxide with an optical rotation power of more than 500° or less than -500°. This candidate's OPR has most probably never been determined computationally. Therefore there is a high chance that the literature values are actually wrong (or not precise) those seem to vary. The experimental unreliability in measuring OPRs has been described above already.

Optimally this epoxide or its alkene precursor would be commercially available from eg. Sigma Aldrich. The candidates suggested here are the diastereomers (1R,4S)-pulegone oxide and (1R,4R)-pulegone oxide, which both fulfill the conditions: Both enantiomers (R)-(+)- and (S)-(-)-Pulegone are offered in Aldrich and their OPR is in the required range according to reaxys.

Overall conclusion

This computational project has yielded interesting results and proven its usefulness in varies examples. Different energies and their contribution to the overall energy can be calculated easily. NMR spectra have measured and compared to the literature values. They compared well despite the TMS error that has not yet been eliminated from computer calculations. NCIs and QTAIMs have been computed, interpreted and their usefulness was evaluated.

While computational chemistry offers a new perspective onto several bonding aspects and molecular behaviour, it also sharpens the understanding of chemistry in the sense that for example transition states can be illustrated and evaluated quite accurately. This is not possible to this extent by experimental analysis only. Thus in conclusion computational chemistry is incredibly helpful and worth considering to confirm experimental data but at the same time should be treated with care as it is based on calculation only and thus cannot consider all influential aspects that are present in the experimental executions. That having been said, it becomes clear that the "perfect" theory cannot predict the real world.

NELQEA -> Shi

TOVNIB -> Jac

- ↑ D. Hönicke, R. Födisch, P. Claus, M. Olson, Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Clayden, Greeves, Warren, Wothers, Oxford Uni. Press, Organic Chemistry

- ↑ S. Elmorel, L. Paquette, Tetrahedron Letters, 1991, 32, 319

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 L. Paquette, N. Pegg, D. Toops,’ G. Maynard, and R. Rogers, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1990, 112, 211

- ↑ E. McGarrigle and D. Gilheany, Chemical Reviews, 2005, 105, 1588

- ↑ M. Mantina, A. Chamberlin, R. Valero, C. Cramer, and D. Truhlar, J. Phys. Chem., 2009, 113, 5806

- ↑ H. Rzepa, Imperial College London, Conformational Analysis - Theory

- ↑ S. Wu, A. Li, Y. Chin, and Z. Li, ACS Catal., 2013, 3, 758

- ↑ K. Stingl, K. Weiß, S. Tsogoeva, Tetrahedron, 2012 68, 8499

- ↑ V. Capriati, S. Florio, R. Luisi and A. Salomone, Org. Lett., 2002, 4, 2445

- ↑ H. Lin, Y. Liua, Z.-L. Wu, Tetra. Asym., 2011 , 22, p. 134

- ↑ D. Fox, D. Pedersen, A. Petersen, S. Warren, Org. and Biomol. Chem., 2006 , 4, 3117

- ↑ J. Read and I. Campbell, J. Chem. Soc., 1930, 0, 2377-2384

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Z. Wang, Y. Tu, M. Frohn, J. Zhang and Y. Shi, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1997, 119, 11228

- ↑ Transition state of (R,R) stilbene used for analysis

- ↑ M. Levitt and M. Perutz, J. Mol. Biol., 1988, 201, 751

- ↑ J. Lane, J. García, J. Piquemal, B. Miller and H. Kjaergaard, J. Chem. Theory Comput., 2013, 9, 3264

- ↑ H. Rzepa, Script for Y3 computational lab 1C