Rep:Mod:NBC1C

The Hydrogenation of Cyclopentadiene Dimer

It should be noticed that all the optimisations in this experiment are carried out using Avogadro.

| Isomer1 | Isomer2 | Isomer3 | Isomer4 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure |

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Force Field | MMFF94s | MMFF94s | MMFF94s | MMFF94s | ||||||||||||

| Algorithm | Conjugate Gradients | Conjugate Gradients | Conjugate Gradients | Conjugate Gradients | ||||||||||||

| Total bond stretching energy/ kcal/mol | 3.54278 | 3.46716 | 3.30864 | 2.82304 | ||||||||||||

| Total angle bending energy/ kcal/mol | 30.77303 | 33.19917 | 30.86391 | 24.68554 | ||||||||||||

| Total stretch bending energy / kcal/mol | -2.04132 | -2.08202 | -1.92667 | -1.65717 | ||||||||||||

| Total torsional energy/ kcal/mol | -2.73109 | -2.94992 | 0.05990 | -0.37838 | ||||||||||||

| Total out-of-plane bending energy/ kcal/mol | 0.01495 | 0.02190 | 0.01539 | 0.00028 | ||||||||||||

| Total van der Waals energy/ kcal/mol | 12.80140 | 12.35073 | 13.28110 | 10.63716 | ||||||||||||

| Total electrostatic energy/ kcal/mol | 13.01372 | 14.18365 | 5.12099 | 5.14702 | ||||||||||||

| Total energy/ kcal/mol | 55.37347 | 58.19066 | 50.72283 | 41.25749 |

As can be seen in the table above, same settings of force field and algorithm are used in order to allow the comparison of energies. As a result, isomer 1 (exo structure, 55.37347 kcal/mol) is lower in energy than isomer 2 (endo structure, 58.19066 kcal/mol), indicating isomer 1 is the more stable and thermodynamically favored product and isomer 2 is the kinetic product which is favored under kinetic control. Isomer 2 is formed faster than isomer 1 because of the lower activation energy of isomer 2, yet it is less stable due to the higher molecular energy.

Total angle bending energy contributes most to the total energy among other dissection energies, the difference between total angle bending energies of isomer 1 and 2 is also the largest, which accounts for the major energy difference between isomer 1 and 2. Angle bending energy of isomer 2 (33.19917 kcal/mol) is larger than that of isomer 1 (30.77303 kcal/mol), this can be explained by the fact that measured angles have larger deviation from ideal hybridisation angles(sp2 C :120°, sp3 C:109.5°).

By comparing the total energy of isomer 3 with that of isomer 4, isomer 4 shows a lower energy than isomer 3. Therefore, isomer 4 is the product under thermodynamic control. There are little difference between the dissection energies of isomer 3 and 4 except for the angle bending energy. The energy difference in angle bending energy can be explained in the same theory as above.

| Isomer9 | Isomer 9* | Isomer 10 | Isomer 10* | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure |

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Force Field | MMFF94s | MMFF94s | MMFF94s | MMFF94s | ||||||||||||

| Algorithm | Conjugate Gradients | Conjugate Gradients | Conjugate Gradients | Conjugate Gradients | ||||||||||||

| Total bond stretching energy/ kcal/mol | 7.63349 | 6.94603 | 7.60077 | 6.57496 | ||||||||||||

| Total angle bending energy/ kcal/mol | 28.28144 | 32.04138 | 18.83483 | 24.73710 | ||||||||||||

| Total stretch bending energy / kcal/mol | -0.08450 | 0.29925 | -0.13931 | 0.42627 | ||||||||||||

| Total torsional energy/ kcal/mol | 0.38399 | 9.49812 | 0.21789 | 8.48774 | ||||||||||||

| Total out-of-plane bending energy/ kcal/mol | 0.97300 | 0.25592 | 0.84256 | 0.06353 | ||||||||||||

| Total van der Waals energy/ kcal/mol | 33.06924 | 32.71211 | 33.24867 | 31.13566 | ||||||||||||

| Total electrostatic energy/ kcal/mol | 0.30709 | 0.00000 | -0.05465 | 0.00000 | ||||||||||||

| Total energy/ kcal/mol | 70.56377 | 81.75280 | 60.55077 | 71.42526 |

There are other isomers present, for example, the twist boat structures. However, they're less stable because of higher energies.

| Structure |

|

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Energy /kcal/mol | 76.46449 | 63.93652 |

Which of the two atropisomers is the more stable?

Isomer 9 has an energy of 70.56377 kcal/mol and the energy of isomer 10 is 10.013 kcal/mol less than that. Therefore, isomer 10 is more stable because it is lower in energy.

Why the alkene reacts slowly?

The difference between the strain energy of an olefin and that of its hydrogenated derivative is defined as olefin strain energy (OS). Isomer 9 and 10 are bridgehead olefins, which can be divided into three groups based on their olefin strain energies. OS ≤ 17 kcal/mol are called isolable bridgehead olefins, which are kinetically stable at room temperature. Olefins with OS higher than 17 kcal/mol are less stable.[2] The OS for isomer 9 is 9.11413 kcal/mol and the OS for isomer 10 is 8.26985 kcal/mol. Both of the values are smaller than 17 kcal/mol which means they're stable and reacts slowly.

Molecule 17 and 18 are optimised using Avogadro (force field: MFF94s) and then a setting of B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) is used to compute their corresponding NMRs. Chloroform is chosen as the solvent when doing the calculation. However, the solvent used in literature is C6D6[3].

| Molecule 17 | Molecule 18 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure |

|

| ||||||

| Calculation type | FREQ | FREQ | ||||||

| Calculation Method | RB3LYP | RB3LYP | ||||||

| Basis Set | 6-31G(D,P) | 6-31G(D,P) | ||||||

| Total Energy/ a.u. | -1651.88240714 | -1651.88157369 | ||||||

| Sum of electronic and thermal free energies/a.u. | -1651.461189 | -1651.460740 | ||||||

| .log File | here | here |

| 1H NMR | 13C NMR |

|---|---|

|

|

| Atom Number | Shift/ ppm | Corrected Shift/ ppm | Literature Shift[3]/ ppm | Degeneracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | 216.1047298 | 219.6605406 | 211.49 | 1 |

| 3 | 145.124741 | 145.124741 | 148.72 | 1 |

| 5 | 124.6849266 | 124.6849266 | 120.9 | 1 |

| 11 | 90.64759911 | 84.64759911 | 74.61 | 1 |

| 8 | 60.63933078 | 60.63933078 | 60.53 | 1 |

| 10 | 57.04499698 | 57.04499698 | 51.3 | 1 |

| 2 | 52.47751049 | 52.47751049 | 50.94 | 1 |

| 1 | 51.54743778 | 51.54743778 | 45.53 | 1 |

| 6 | 46.69312938 | 46.69312938 | 43.28 | 1 |

| 46 | 45.95379184 | 42.95379184 | 40.82 | 1 |

| 12 | 42.17199765 | 42.17199765 | 38.73 | 1 |

| 45 | 40.57497339 | 37.57497339 | 36.78 | 1 |

| 7 | 35.3285884 | 35.3285884 | 35.47 | 1 |

| 4 | 31.01138079 | 31.01138079 | 30.84 | 1 |

| 13 | 29.35321102 | 29.35321102 | 30 | 1 |

| 21 | 29.32217151 | 29.32217151 | 25.56 | 1 |

| 36 | 27.09236319 | 27.09236319 | 25.35 | 1 |

| 28 | 26.40358177 | 26.40358177 | 22.21 | 1 |

| 14 | 22.90364275 | 22.90364275 | 21.39 | 1 |

| 32 | 19.72646 | 19.72646 | 19.83 | 1 |

Chemical shifts for atom 9, 45 and 46 of molecule 17 are corrected because of their attachments to heavy elements and the corresponding spin-orbit coupling errors. Corrected value for atom 9 is calculated by using the equation δcorr = 0.96δcalc + 12.2. The corrections for atom 45 and 46 (C-S) is estimated to be -3 ppm based on the correction for C-Cl (-3 ppm), because no corresponding literature value is found and sulfur and chlorine atoms are next to each other within the same period in periodic table.

An analysis is taken by taking the difference between each corrected 13C shifts and literature values, the graph is plotted above. It can be seen that while the majority of the deviations are under 5 ppm, there are still some deviations have values above that. For example, atom 9 has a deviation of 8.1705406 ppm. But it should be noticed that atom 9 of molecule 17 connects to 2 sulfur atoms, and the NMR shift correction for atoms connect with sulfur atom is estimated. Besides, there could be a bigger impact on the atom 9 since it connects with 2 sulfur atoms, which makes the value unreliable. Due to the reason that most of the values show a good match with literature values, it can be deduced that the literature values with large deviation with this experiment are wrong.

| Atom Number | Shift/ ppm | Literature Shift[3]/ ppm | Degeneracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| 17 | 5.150921272 | 5.21 | 1 |

| 50 | 3.308126287 | 3.00-2.70 | 1 |

| 49 | 3.221071967 | 1 | |

| 20 | 3.158522394 | 1 | |

| 47,48 | 3.028805078 | 2 | |

| 40,19 | 2.72977565 | 2 | |

| 34 | 2.635042805 | 2.70-2.35 | 1 |

| 37,38,22,18 | 2.396951168 | 4 | |

| 39,42 | 2.276827035 | 2.20-1.70 | 2 |

| 25,16 | 2.129430447 | 2 | |

| 23 | 1.954108422 | 1 | |

| 26 | 1.903859149 | 1 | |

| 53 | 1.744331831 | 1 | |

| 41,27,29 | 1.59509974 | 1.58 | 3 |

| 24 | 1.489509991 | 1.50-1.20 | 1 |

| 51 | 1.164851679 | 1 | |

| 31,35,30 | 0.915513841 | 1.10 | 3 |

| 33 | 0.82411982 | 1.07 | 1 |

| 52 | 0.591931279 | 1.03 | 1 |

1H NMR of molecule 17 is also analyzed and compared with literature values. In general, it shows a bad match with literature. The deviation of chemical shifts have a tendency of increasing as the chemical shifts become less positive. Therefore no conclusion can be drawn regarding which set of data is correct.

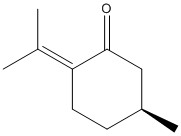

Analysis of the properties of the synthesised alkene epoxides

The two catalytic systems

Cambridge crystal database (CCDC) is searched by using the Conquest program, the following structures of pre-catalysts 21 and 23 are found. Mercury program is then used to measure the C-O bond lengths of three anomeric centres of Shi catalyst.

| Shi Catalyst (21) | Jacobsen Catalyst (23) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

It can be seen on the diagram that on each anomeric centres(O-C-O), one C-O bond length is longer than another. Even though the diagram displays an equal bond length for the C-O bonds in the middle anomeric centre, Mercury program shows a more accurate result, one C-O bond is 1.415 Å while another is 1.423 Å. The difference between the C-O bond lengths can be explained by anomeric effect. Hyperconjugation between the lone pair on the oxygen atom and the σ* orbital for the C-O bond strengthens the C-O bond which makes it shorter. In the contrary, another C-O bond is lengthened because of the extra electron density on the σ* orbital.

By analyzing the two adjacent t-butyl groups on the rings of Jacobsen catalyst, it is found that the hydrogen atoms of one methyl group are quite close to the hydrogen atoms on the opposite methyl group of t-butyl. With one distance of 2.08 Å which is shorter than the Van der Waals radii (2.20 Å [4]) for two hydrogen atoms, indicating an interaction exists between the two hydrogen atoms. This leads to an enhanced catalyst selectivity due to the fact that t-butyl groups prevent substrate approach metal centre from its side[5]. It is interesting to notice that some H atoms from t-butyl groups have a close proximity to the oxygen atoms (e.g. 2.22 Å), which means the interaction between H an O might also contributes to the selectivity of catalyst.

NMR properties of products

β-methyl styrene and trans-stilbene are chosen for this section and their epoxides products are analyzed. By comparing the calculated NMR data with literature values, the calculated values are indicated to be reasonable.

| β-methyl styrene epoxide | trans-Stilbene epoxide | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strucutre |

|

| ||||||

| 1H NMR |  |

| ||||||

| 13C NMR |  |

| ||||||

| D-Space | DOI:/10042/26177 | DOI:/10042/26178 |

| Atom Number | Shift/ ppm | Literature Shift[6] / ppm | Degeneracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| 14 | 7.5005789387 | 7.17-7.28 | 3 |

| 11 | 7.4965353149 | 3 | |

| 13 | 7.4764056286 | 3 | |

| 12 | 7.4215078669 | 1 | |

| 15 | 7.3072832156 | 1 | |

| 16 | 3.4146796724 | 3.688 | 1 |

| 17 | 2.7878820719 | 3.243 | 1 |

| 19 | 1.6782269670 | 1.287 | 1 |

| 18 | 1.5872817485 | 1 | |

| 20 | 0.7169440684 | 1 |

| Atom Number | Shift/ ppm | Degeneracy |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | 134.9753965424 | 1 |

| 1 | 124.0725177924 | 1 |

| 3 | 123.3280431186 | 1 |

| 4 | 122.7961719799 | 1 |

| 2 | 122.7269092928 | 1 |

| 6 | 118.4861712952 | 1 |

| 9 | 62.3200384786 | 1 |

| 7 | 60.5763422400 | 1 |

| 10 | 18.8378278486 | 1 |

| Atom Number | Shift/ ppm | Literature Shift[7] / ppm | Degeneracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 134.0880446109 | 137.6 | 2 |

| 9 | 134.0879314162 | 2 | |

| 11 | 124.2199442902 | 129.0 | 2 |

| 1 | 124.2199347937 | 2 | |

| 3 | 123.5184078463 | 128.8 | 2 |

| 13 | 123.5183926697 | 2 | |

| 12 | 123.2119589779 | 2 | |

| 2 | 123.2119101109 | 2 | |

| 14 | 123.0785722351 | 2 | |

| 4 | 123.0784012095 | 2 | |

| 10 | 118.2628347616 | 126.2 | 2 |

| 6 | 118.2627684281 | 2 | |

| 7 | 66.4265991815 | 63.3 | 2 |

| 8 | 66.4265484152 | 2 |

| Atom Number | Shift/ ppm | Literature Shift[7] / ppm | Degeneracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| 21 | 7.5704385557 | 7.57-7.34 (10H) | 2 |

| 15 | 7.5704374374 | 2 | |

| 18 | 7.5069643263 | 8 | |

| 24 | 7.5069578119 | 8 | |

| 17 | 7.4896480510 | 8 | |

| 23 | 7.4896464357 | 8 | |

| 22 | 7.4691926261 | 8 | |

| 16 | 7.4691895198 | 8 | |

| 19 | 7.4507152761 | 8 | |

| 20 | 7.4507076434 | 8 | |

| 27 | 3.5377977258 | 3.91 (2H) | 2 |

| 26 | 3.5377374275 | 2 |

Assigning the absolute configuration of the product

Optical rotation of epoxide products are calculated and compared with literature values, giving the table shown below. The solvent used for calculation is chloroform. It should be noticed that all values in this section are taken at 589 nm.

| β-methyl Styrene Epoxide | Trans-Stilbene Epoxide | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SS | RR | SS | RR | |||||||||||||

| Structure |

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Calculated Optical Rotation Solvent:CHCl3 | -46.77° | +46.77° | -298.00° | +298.00° | ||||||||||||

| Literature Optical Rotation Solvent:CHCl3 | -48.5° [8] | +47°[9] | -249° ( 15 °C)[10] | + 250.8°[11] | ||||||||||||

| Others Literature Optical Rotation | -50.1° (CHCl3)[12] | +131° (Benzene)[13] | -384° (Ethyl Acetate,15 °C)[10] |

+361°(PhH)[14] | ||||||||||||

Overall, the calculated results demonstrate a good match with literature values, therefore structures shown above are the correct assignments of absolute configurations of epoxide products. Different literature values are also being compared to each other, generally, the deviation is small when the same solvent is used.

It is found that different solvents have a profound impact on the optical rotation value. For example, literature value for (R,R)β-methyl styrene epoxide is +47°[9], which is a great match with calculated value (+46.77°), the literature value increases to +131° [13] when product is dissolved in benzene instead of chloroform. More examples of solvent effects are also shown in the table above.

Free energy difference between two diastereomeric transition states is calculated by using data from the most stable group of transition states. K is then calculated using the equation, . Summaries of calculations are shown in the tables below.

| Trans-β-methyl Styrene Epoxide (Group 4 Data) | ||

|---|---|---|

| R,R | S,S | |

| Free Energy /Hartree | -1343.032443 | -1343.024742 |

| Free Energy Difference (RR-SS) /kJ/mol | -20.2189755 | |

| K | 3596.649285 | |

| Population | 99.97% | 0.03% |

| Enantiomeric Excess | 99.94% (R,R) | |

| Cis-β-methyl Styrene (Group 1 Data) | Trans-β-methyl Styrene (Group 1 Data) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S,R | R,S | S,S | R,R | |

| Free Energy /Hartree | -3383.259559 | -3383.251060 | -3383.262481 | -3383.253816 |

| Free Energy Difference (SR-RS, SS-RR) /kJ/mol | -22.3141245 | -22.7499575 | ||

| K | 8118.494422 | 9679.254069 | ||

| Population | 99.99% | 0.01% | 99.99% | 0.01% |

| Enantiomeric Excess | 99.98% (S,R) | 99.98% (S,S) | ||

It can be seen from the tables that, for trans-β-methyl styrene, (R,R)trans-β-methyl styrene epoxide will be synthesized when Shi catalyst is used, with an enantiomeric excess of 99.94%. However, when Jacobsen catalyst is used, the dominate product will be (S,S)trans-β-methyl styrene epoxide, with an enantiomeric excess of 99.98%. This difference is caused by the stereoselectivity difference of the two catalysts. For (S,R)cis-β-methyl styrene, calculated value of enantiomeric excess is 99.98%, which is a reasonable result compared to literature value of 92%[5].

By comparing transition states in different energies, it is discovered that the most stable form of transition state is the one with the best "overlap" between alkene and the catalyst. For example, (R,R)β-methyl styrene epoxide (group 4) is more table than that of group 2 because the benzene ring has a better "overlap" with Shi catalyst.

| Group 4 | Group 3 | |

|---|---|---|

| Structure |  |

|

| Relative Energy kJ/mol | 0 | 8.3254605 |

The vibrational circular dichroism (VCD)of each diastereomer is calculated using GaussView. Results is shown in the table below.

| β-methyl Styrene Epoxide | ||

|---|---|---|

| SS |  |

|

| RR |  |

|

It's easy to notice that results for VCD of diastereomers are completely opposite to each other, this is because diastereomers are mirror image to each other. The electronic circular dichroism (ECD) is not practical in this experiment because there's no chromophore in the molecule.

Investigating the non-covalent interactions in the active-site of the reaction transition state

(R,R)trans-β-methyl styrene transition state (Shi catalyst, group 4) is used for non-covalent interactions (NCI) analysis, giving the following result.

Orbital |

Colours in the diagram represent the attractiveness of the interaction, blue is very attractive, green is mildly attractive, yellow is mildly repulsive and red is strongly repulsive. There are large green areas between the oxygen atom (in colour pink) of active catalyst and substrate molecule, indicating a strong interaction between them, which is a origin of stereoselectivity.

QTAIM

Arrow 3 in the graph indicates a BCP (bond critical point). There are other types of critical points in the diagram, but they're not considered in this experiment. Arrow 1 indicates a weak non-covalent BCP, which is associated with weak interaction between oxygen and hydrogen. Electronic topology (QTAIM) confirms the suggestion from previous section, because there are two BCP (arrow 1 and 2) associate with the pink oxygen atom.

New Candidate

The following molecule is suggested for further investigation. It is know that D-pulegone is commercially available on Sigma-Aldrich, more details can be found here

| Name | D-pulegone |

|---|---|

| Structure |  |

| Reaxys Registry Number | 3588094 |

| CAS Registry Number | 89-82-7 |

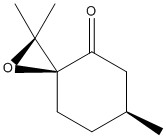

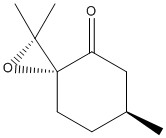

| (R)Pulegone Oxide | (S)Pulegone Oxide | |

|---|---|---|

| Structure |  |

|

| Optical Rotation Literature, Solvent: Ethanol | 786.5 (293 nm)[15] | -1177.9 (327 nm)[15] |

Literature value is listed above for future reference.

References

- ↑ Generalised energy profile diagram for kinetic versus thermodynamic product reaction, 2012<.http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Thermodyamic_versus_kinetic_control.png>

- ↑ W. F. Maier and P. v. R. Schleyer, "Evaluation and Prediction of the Stability of Bridgehead Olefins", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1981, 103, 1891.DOI:10.1021/ja00398a003

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 L. Paquette, N. A. Pegg, D. Toops, G. D. Maynard, R. D. Rogers, J. Am. Chem. Soc.,, 1990, 112, 277-283. DOI:10.1021/ja00157a043

- ↑ M. Mantina, A. C. Chamberlin, R. Valero, C. J. Cramer, and D. G. Truhlar J. Phys. Chem., 2009, 113, 5810. DOI:/10.1021/jp8111556

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 E. N. Jacobsen , W. Zhang , A. R. Muci ,J. R. Ecker , L. Deng,J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1991, 113, 7063–7064; DOI:10.1021/ja00018a068

- ↑ M. Sangaa, I. R. Younisa, P. S. Tirumalaia, T. M. Blanda, M. Banaszewskab, G. W. Konatb, T. S. Tracyc, P. M. Gannetta, P. S. Callery Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 2006, 211, 152. DOI:/10.1016/j.taap.2005.06.017

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 M. W. C. Robinson, A. M. Davies, R. Buckle, I. Mabbett, S. H. Taylora and A. E. Graham Org. Biomol. Chem., 2009, 7, 2562. DOI:/10.1039/B900719A

- ↑ P. Besse, Michel F. Renard, H. Veschambre, Tetrahedron: Asymmetry, 1994, 5, 1268. DOI://10.1016/0957-4166(94)80167-3

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 G. Fronza, C. Fuganti, P. Grasselli, and A. Mele J. Org. Chem., 1991, 56, 6023. DOI://10.1021/jo00021a011

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 J. Read, I. G. M. Campbell J. Chem. Soc., 1930, 2382. DOI://10.1039/JR9300002377

- ↑ D. J. Fox, D. S. Pedersen, A. B. Petersen, S. Warren, Org. Biomol. Chem., 2006, 4, 3117-3119.

- ↑ H. C. Kolb, K. B. Sharpless, Tetrahedron, 1992, 48, 10521.DOI://10.1016/S0040-4020(01)88349-6

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 M. Rosenberger, W. Jackson, G. Saucy, Helvetica Chimica Acta, 1980, 63, 1665 - 1674.

- ↑ H. T. Chang, K. B. Sharpless, J. Org. Chem., 1996, 61, 6457.DOI://10.1021/jo960718q

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 W. Reusch, C. K. Johnson, J. Org. Chem., 1963, 28, 2557-2560. DOI:10.1021/jo01045a016