Rep:Mod:MgO modelling

Abstract

The present work focuses on the computational study of an MgO crystal. Although a simple structure, its modelling can also reveal important information about similar structures, like similar metal oxides(i.e. CaO). Additionally, the physical models used for these computations can also model other crystal structures and predict useful properties of other important solids. Calculations were successfully run first for phonons to give a quantum mechanical description for thermal expansion both at low (0-400 K) and mild (450-1000) temperatures. Then Molecular Dynamics simulations were performed to study thermal expansion in the classical limit (not at low temperatures). Such results are incredibly insightful and used not only in physics and chemistry, but also in many other areas, like geology.The understanding developped using these simulations is invaluable to anybody willing to study solid state physics and it is also a great starting point for the research of the properties of solid crystals.

Introduction

The study of crystal structure is extremely important not only in chemistry, but also in other subjects, like geology1. In geology, scientists can analyse the different types of rocks to be able to infer something regarding the physical conditions leading to the corresponding crystal structures. Of course, this requires knowledge about the internal energies of solid crystals. But in chemistry the study of crystals is maybe even more important, because crystal structures can nowadays be analysed using modern techniques, such as X-ray diffraction. This method reveals the crystal structure of the analysed compound, which can be then modeled theoretically in order to obtain some important chemical properties. To illustrate the theoretical modeling of crystals, Magnesium oxide (MgO) was used and its cubic lattice was analysed. The main objective is investigating the vibrational modes (phonons) of this crystal and how they can link external conditions to its physical properties, namely temperature to volume (through thermal expansion).

Methodology

All calculations and simulations that are going to be presented here were done using the software called GULP (General Utility Lattice Program). The possibilities offered by GULP allowed for at least two approaches, which were used in the present work. The first part is focused on the calculations of internal energy and phonons. The second part includes computations of the Helmholtz free energy based on the harmonic approximation and the lattice constant and thermal expansion coefficient using the quasi-harmonic approximation. The final part, on the other hand, uses a completely different approach; the results obtained using the quasi-harmonic approximation were compared against others, predicted by a Molecular Dynamics simulation.

Binding energy of MgO

In order to calculate the internal energy of an MgO crystal lattice one has to implement a potential energy model for the interaction between a magnesium atom and an oxygen atom. For the present simulation, a very simple model was used, one which considers this interaction to be purely electrostatic. Consequently, electric charges of +2e and -2e are imposed on magnesium and oxygen respectively. The mathematical description used is a function called Coulomb-Buckingham potential2:

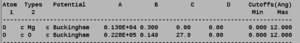

Here A, B and C are constants calculated from experimental measurements. The first two terms represent the traditional Buckingham potential, which describes the repulsion between two atoms at small distances. The third term is the well-known coulomb potential, describing the interaction between two charged spheres. An important observation is how small the first two terms become compared to the third one at large distances. This property of the Buckingham potential ensures that it does not interfere mathematically with the values of the coulomb potential at distances where repulsion is no longer present. A quick summation of the GULP software over all interactions gives the binding energy of the crystal. Finally, the parameters used too compute the interatomic potential energy are given in fig. 1.

Phonons of MgO

Phonons of MgO: The phonon dispersion curves were computed in order to animate a few vibrational modes and visualize them. The calculations were executed by summing over 50 k values in reciprocal space. Afterwards a more important property was calculated, which is the phonon density of states. There is a direct link between these physical quantities. By definition, phonon density of states is the number of states having energies in a particular (infinitesimal) energy interval .

By analysing the dispersion curves one can extract information about the density of states. The dispersion curves are esentially emergies as funcitons of k values (plots f the dispersion relations). From the definition above, it is clear the density of states is the inverse of the slope of the dispersion curve. In other words, a region with small slope along a dispersion curve indicates high density of states for that energy region and vice versa. The reason density of states is so important is because it indicates the optimum size for the grid of k points used for summation over the states. In practice, a crystal structure is almost infinite from a microscopic viewpoint. Therefore, it is expected a summation using an infinite grid will provide the most accurate answer. Unfortunately, the available computational resources are not able to deal with such a task. However, as the grid size increases, the sampling resolution of the states becomes higher. All that is needed is a high enough resolution to produce a satisfactory approximation of the infinite grid.

Helmholtz free energy in the quasi-harmonic approximation

The Helmholtz free energy was computed, at this stage, at 300 K and 0 K. The mathematical description of the free energy, in this case, relies on the modelling of interatomic potential energies by the Buckingham-Coulomb potential, presented in the previous subsection. Considering the temperatures are not very high, the individual vibrations are all in the ground state, and the energies of these ground states can be approximated by . A very accurate expression is given by a summation over all these individual vibrations3:

As the summation signs also indicate, the free energy is computed by summing over all possible states. Therefore, the higher the resolution of these states, the better the approximation. This is why the density of states calculation is required prior to free energy computation.

It is also important to note that this model can definitely predict qualitatively the behaviour of the free energy. However, the numerical value might deviate from experimental results and is guaranted to work well in the region where the approximations are valid. There might be a problem, for instance, with the Buckingham-Coulomb potential, which might not give a very good description at large interatomic separations. Also, regarding thermal expansion, the quasi-harmonic model should break down at very large temperatures (close to the melting point). A crystal can thermally expand because high temperatures lead to high vibrational levels on the Buckingham-Coulomb potential curve, 'located' in the wide region of the potential curve, where the bond length is larger. Nevertheless, a finite increase in temperature, no matter how large, will not be able to break the bonds according to this model. Therefore, a continuous expansion is expected from the computations, but there would be no prediction of a melting point. In reality, at temperatures close to the melting point the entropy is quite high and atom movements start getting more chaotic, so a vibration model is no longer valid under such circumstances. Still, the quasi-harmonic model is good enough to predict thermal expansion. A harmonic model, on the other hand, would fail at predicting this effect, because if the potential energy curve is symmetric (i.e. a parabola) there can be no change in bond length.

Thermal expansion of MgO

The same physical quantity, Helmholtz free energy was computed, only this time, for multiple temperature values. This time the values of the lattice constant and the primitive cell volume were also used, especially for calculating the coefficient of thermal expansion, in the linear regime (where volume changes linearly with temperature).

Molecular dynamics simulation

Molecular dynamics is a method that relies entirely on classical mechanics rather than employing any quantum approximation. It is an interative process that computes the positions and velocities of atoms according to Newton's laws and lets the system evolve in time. More specifically, it takes the same initial positions as the ideal MgO lattice and assignes velocities randomly, aiming for the desired temperature. Then, for every step it computes the accelerations (from forces) and uses them to update the positions and velocities. For a time step an atom i, of mass , initial position and initial velocity the equations of motion can be written as:

For the present simulation an MgO lattice size of 32x32x32 was used, with an 500 equilibration steps, 500 production steps, 5 sampling steps, 5 trajectory writing steps and a time step of 1 femtosecond. The simulation was performed for the same temperature values as the quasi-harmonic simulation, except for 0 K, where there is no dynamics.

Results and discussion

Binding energy of MgO

This first and very fast calculation gave a binding energy of –41.075531759 eV. This value clearly shows a tendency of free magnesium and oxygen atoms to combine and form a crystal lattice, and it also shows the great stability of such a structure.

Phonons of MgO

Computation of the phonon dispersion curves led to the following diagram:

|

From this picture one can distinguish four important curves: the bottom three, which cross the Γ point at a frequency ν=0, and the top one. The bottom three (in this case) curves are known as acoustic branches, while the top one is known as the optic branch. The evaluation of the phonon density of states led to significantly different results for different small k-space grid size. The evolution can be seen in the following figures:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

First of all, it is interesting to note that for a 1x1x1 grid only one k-point was computed, and is represented by four peaks (each corresponding to a vibrational state) in the density of states graph. A quick comparison of these four frequency values with the frequencies calculated for the dispersion curve allows an easy identification of this k point as L. An even easier labeling of this point can be done by looking at the dispersion curves, because the four states in their respective frequency regions can be easily identified with the four points where the dispersion curves cross the L vertical line. From a quick examination of the plots above one notices the density of states increases with grid size for any frequency range. The reason is that when the grid becomes larger more vibrational modes are sampled, some modes with frequencies where smaller grids showed no states. As the grid size increases, therefore, the density of states curve becomes smoother and smoother, until the change becomes unnoticeable. For this calculation, in particular, this happens for a grid size of roughly 30x30x30. This is the optimum size, giving a curve that does not differ visibly from the density of states curve of an infinite grid. So for a smaller grid the curves are less smooth, while for a larger one the curves are essentially the same. However, in order to get more precise calculations, a grid of 40x40x40 was used from this point onwards. It is important though, not to forget other solid crystals are important as well. But for the computation of a different crystal, how would the optimum grid size compare to that of MgO? This question can effectively be answered without any further computation. All that is needed is the link between the lattice constant in real space and the lattice constant in reciprocal space. For a cubic lattice, the relationship is . Therefore, if the real lattice is smaller, (i.e. for Lithium) the reciprocal lattice is larger, and a larger grid is needed to get the optimum density of states curve. If the lattice sizes is comparable in real space (i.e. CaO vs MgO), the same will happen in reciprocal space, so a grid of the same size will most likely suffice. On the other hand, for a much larger lattice (i.e. zeolites), a relatively small grid in reciprocal space will give the desired resolution for the density of states.

Helmholtz free energy in the quasi-harmonic approximation

As the grid size increases, one expects the Helmholtz free energy to change. If the grid is large enough, the free energy value will reach a limit, it will reach the energy of an infinite grid. In order to obtain an optimum grid size for the free energy computation the calculations were run at 300 K for multiple grid sizes. The results are presented in the table below:

| Grid size | Helmholtz free energy/eV |

|---|---|

| -40.930301 | |

| -40.926609 | |

| -40.926432 | |

| -40.926450 | |

| -40.926463 | |

| -40.926471 | |

| -40.926475 | |

| -40.926478 | |

| 40.926479 | |

| -40.926480 | |

| -40.926481 | |

| -40.926481 | |

| -40.926482 | |

| -40.926482 | |

| -40.926482 |

It is easily noticeable different grid sizes give different accuracies in terms of the free energy result. For example, for an error within 1 meV a 3x3x3 grid gives an error within 1 meV. Likewise, if an error within 0.5 meV is desired the best grid size becomes 4x4x4, and a 7x7x7 grid is required for 0.1 meV. The values oscillate a little for a grid smaller than 3x3x3. However, for larger grid sizes the free energy becomes more and more negative, approaching the limit corresponding to the infinite grid. This behavior is also predicted by the free energy equation. As the number of sampled states increases, so does the first summation , hence adding a positive value to E0. In the meantime, the second summation also gets more terms, all of which are negative, and relatively large because of the 300 K temperature. This second summation, therefore, has a stronger impact on the free energy, making its value to decrease at 300 K. At 0 K, on the other hand, the free energy is expected to increase (become less negative). This happens because the second summation is 0 and the first one increases with the number of states (and grid size implicitly). The data in the table below confirm these expectations:

| Grid size | Helmholtz free energy/eV |

|---|---|

| -40.90428319 | |

| -40.90204252 | |

| -40.90191411 | |

| -40.90190737 | |

| -40.90190632 | |

| -40.90190618 | |

| -40.90190618 |

Of course these sizes work very well for a similar oxide lattice, like CaO, but they have to be changed for other lattices. For metals like Lithium, where the real space cell is small, a larger grid is required to get the free energy value to the same level of accuracy as that of MgO. Conversely, a significantly larger cell, like that of a zeolite, can be modeled using a smaller grid. This happens because the lattice constant in reciprocal space is inversely proportional to the lattice constant in real space.

Thermal expansion of MgO

The first theoretical method for modeling thermal expansion used in the present work is quasi-harmonic approximation. The computation of the Helmholtz free energy shows a decrease with temperature, as indicated int fig. 10.

|

This behaviour is consistent with the free energy equation presented in the Methodology section.The first summation remains unchanged as it does not depend on temperature. However, in the second summation every term becomes more negative as temperature increases. More specifically, as temperature increases the exponent gets closer to 0, resulting in an exponential getting close to 1. Thus, the natural log value decreases towards ; higher temperature gives a more negative free energy.

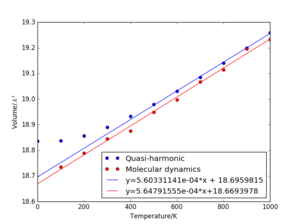

A crucial parameter for the investigation of thermal expansion is volume. In fig. 11 and fig. 12 the behaviour of the primitive cell volume and lattice constant is shown.

|

|

The trend in these cases is again, consistent with the quasi-harmonic approximation. When temperature changes between 0 K and 200 K the volume does not change significantly. This happens because at these low temperatures only the ground state vibrational level is accessible, so the average bond lengths are the same as the equilibrium ones on the potential energy curve. For significantly higher temperatures (450-1000 K) the volume increase is linear because the anharmonic effects come into play. The average bond lengths increase with temperature according to this approximation. The anharmonic effects also make the energy gaps between consecutive vibrational levels decrease as we go to higher levels. In the linear regime the energy gap between two consecutive levels is much smaller then thermal energy , so the spectrum of vibrational levels appears continuous (the classical limit is obtained). The same trend is observed for the lattice constant.

Considering the definition of the thermal expansion coefficient, one can notice immediately from fig. 11 that it is temperature dependent. However, outside the low temperature range the increase of primitive cell volume with temperature becomes approximately linear, leading to a roughly constant thermal expansion coefficient. A linear fit was performed outside the low temperature region in order to estimate the coefficient. In this linear regime, the gradient is constant, so the coefficient can be written as:

In this case is taken as the volume at 0 K predicted by the linear fit. In this case, . Because has been chosen like this, the volume at any temperature T in this linear regime can be expressed as

Substituting the values for the gradient and gives the value of the expansion coefficient:

Molecular Dynamics simulation

Results of the Molecular Dynamics simulation are presented in the figure below.

|

On the same graph one can see the results of both methods, quasi-harmonic approximation and Molecular Dynamics. An interesting observation to make is the difference the two results exhibit at low temperatures. While the quasi-harmonic approximation predicts a constant volume at temperatures below 200 K, Molecular Dynamics predicts a linear increase even in this range. This effect can be explained by going back to the fundamentals of harmonic oscillation. Classical mechanics gives a continuous energy spectrum for a quasi-harmonic system, with its minimum value equal to 0. So in the classical approach the energy keeps decreasing until it reaches 0. The more realistic quantum approach takes into account the discrete energy spectrum of the oscillator. Therefore, the minimum energy is predicted to be and because of this the molecule remains in the ground state for any temperature between 0 and 200 K. At higher temperatures (450-1000 K) many more vibrational states become available because becomes significantly larger than the energy gap between two consecutive states, mostly because of the anharmonic behaviour. So in this temperature range the vibrational energy levels are very close to each other, and the spectrum starts looking less discrete. This is, therefore, the region where the classical model of a continuous energy spectrum starts being realistic and gets closer to the quantum prediction.

One last numerical comparison between the two methods has to be done, by looking at the predicted expansion coefficients. From the Molecular Dynamics simulation, the calculated coefficient is:

The value is very close to the one predicted by the quasi-harmonic approach. This means that above 450 K, where the expansion is roughly linear, both models work well.

Fig. 13 also shows some fluctuations of the volumes in the classical approach. Decreasing the fluctuations can be easily done by increasing the lattice size, at the cost of some computation time. Considering in the quasi harmonic approximation a lattice of 40x40x40 was excellent for computing the free energy, it should also suffice in diminishing the fluctuations encountered in Molecular Dynamics.

One final difference worth thinking about is between the predictions of the two models at very high temperatures (close to the melting point). Because the quasi-harmonic approach models vibrations it cannot predict realistically what happens once the atoms escape the potential well (oncethe bond breaks). Molecular Dynamics uses classical mechanics to describe the motionof the atoms inside the well, but atoms will also move according to the same laws (in the classical limit) outside the well, so it can be used, if needed, to predict a phase transition and estimate the melting point.

Conclusion

Computational investigation of the MgO crystal gave important insight on how temperature affects the size of the crystal and why it happens. Both the quasi-harmonic and Molecular Dynamics methods predicted thermal expansion and the values of the expansion coefficient agree in the linear regime (where both models are supposed to work well). However, the understanding developped along the way also revealed their limitations; the impossibility for the Molecular Dynamics model to correctly predict the expansion at low temperatures (0-200 K) and the failure of the quasi-harmonic model to predict the melting of the crystal. Even with these limitations, the computation showed how the MgO crystal behaves and the findings might constitute a solid base for future research of solids.

References

1. R. A. Buckingham, Proc. R. Soc. London A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci., 1938, 168.

2. J. M. García-Ruiz and F. Otálora, in Handbook of Crystal Growth, Elsevier, 2015, vol. 2, pp. 1–43.

3. M. T. Dove, Mater. Today, 2003, 6.