Rep:Mod:Lemon

COMPUTATIONAL LABORATORIES - AUTUMN 2008 - Module 2 (Inorganic)

Part 1 - An Introduction

Optimization and Geometry Analysis

BH3

Trigonal planar BH3 has relatively high-symmetry point group D3h, possessing a C3 and 3C2 axes, 3σv planes of symmetry and a σh plane of symmetry.

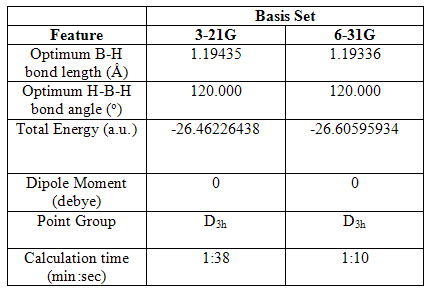

On optimising (FOPT) the structure using the B3lyp method and low 3-21G basis set, the H-B-H bond angle was the expected 120.000o and the B-H bond length 1.19435Ǻ. A further optimisation was then carried out using a higher basis set, 6-31G, to analyse its effects. The angle was again 120.000o, but the B-H bond length decreased to 1.19336 Ǻ. The outputs from these optimisations were of file type .log.

The effect of using a higher level basis set for optimising the molecule can be seen by comparing the energies of the two structures. The 3-21G output gave an energy of -26.46226438 a.u, whereas that of the 6-31G output molecule was -26.60595934 a.u. The use of the 6-31G basis set meant that a more stable geometry of the molecule could be described, which could not be done with the 3-21G basis set. The dipole moment of both structures was 0, which is due to the symmetry of the molecule: the three minute bond dipoles cancel each other out. As expected, both point groups are given as D3h.

Table 1 Selected geometric and physical data of trigonal planar BH3, following various optimisations

The calculation for the initial optimization, using the lower level basis set actually took longer than the calculation using the better basis set but this is because the latter optimization was done following the former, and therefore the structure had, to some extent, all ready been optimized. This shows the importance of running minor optimizations before a final high level optimization is carried out. If however, the initial optimization had not been done, the second optimization would have taken much longer.

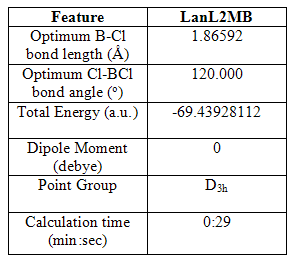

BCl3

If heavier atoms are present in a molecule, the time of the calculation starts to become an issue, and there is a limit on the size of the basis set used. Pseudo potentials can be used on heavier atoms to make calculations faster(?), and therefore, more accessible. An optimization of BCl3 was carried out using the B3Lyp method and LanL2MB basis set, which gave the following results:

Table 2 Selected geometric and physical data of trigonal planar BCl3, following B3lyp/LanL2MB optimisation

The bond angle is again 120.000o and the point group is D3h. The bond length is much greater, which is due to the larger size (larger number of electrons and so more diffuse orbitals) of the chlorine atom. The calculation was faster than both the 3-21G and B-31G basis sets despite the larger chlorine atom.

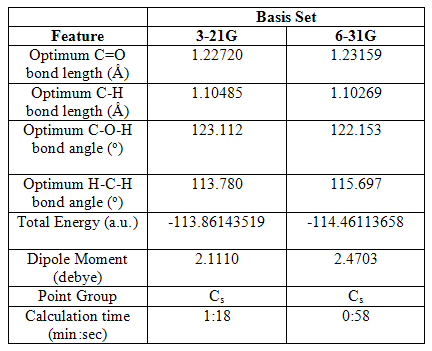

CH2O

The information provided by Gaussview is especially useful when features such as the optimized bond angle cannot be so easily predicted. A B3lyp optimization was carried out on CH2O, again using the 3-21G and 6-31G basis sets, to obtain information regarding its geometry. The results from this optimization can be found at DOI:10042/to-1103 .

Table 3 Selected geometric and physical data of CH2O following various optimizations

It can be seen from these results that the COH angle has increased from the 120o H-B-H angles seen in the trigonal planar BH3 molecule, and this has been compensated for by the compression of the H-C-H bond angle. The C-H bond lengths are shorter than those seen in BH3 perhaps because of the electron withdrawing effects of the oxygen atom within the carbonyl bond, which pull electron density away from the C-H bond, forcing the hydrogen atoms to move inwards. The dipole moment now present is also a result of the electron withdrawing effects of the oxygen atom.

Another useful output from Gaussian calculations are the coordinates of the optimized structure, which allow for its re-creation without running the optimization again. The coordinates of the final optimized structure of CH2O are as follows:

Standard orientation:

--------------------------------------------------------------------- Center Atomic Atomic Coordinates (Angstroms) Number Number Type X Y Z --------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 6 0 0.000002 0.542443 0.000000 2 1 0 -0.933597 1.129223 0.000000 3 1 0 0.933565 1.129280 0.000000 4 8 0 0.000002 -0.689145 0.000000 --------------------------------------------------------------------- Rotational constants (GHZ): 287.6725934 37.3501842 33.0580658

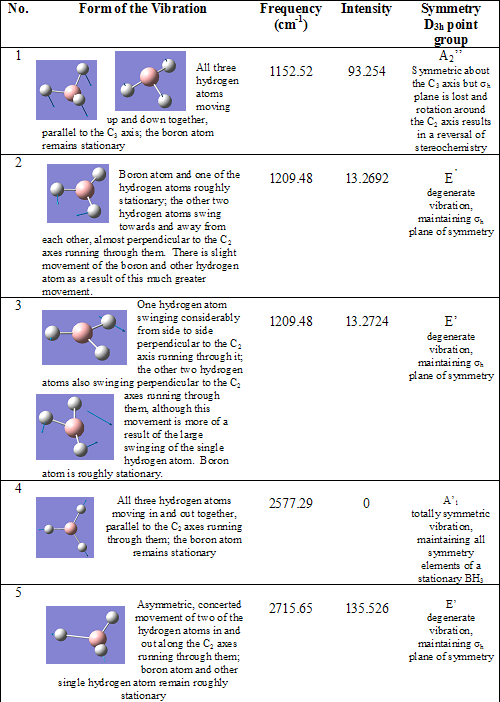

Vibrational Analysis – BH3

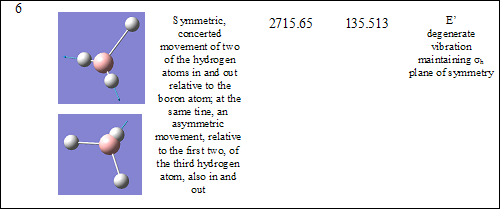

Once an optimized structure has been obtained, computer modeling can then be used to calculate the modes and energies of the bond vibrations present within a molecule and predict its IR spectrum. Such an analysis was carried out on D3h BH3. The results are shown below:

Table 4 Vibrational modes of optimized BH3 with their associated energies and symmetries

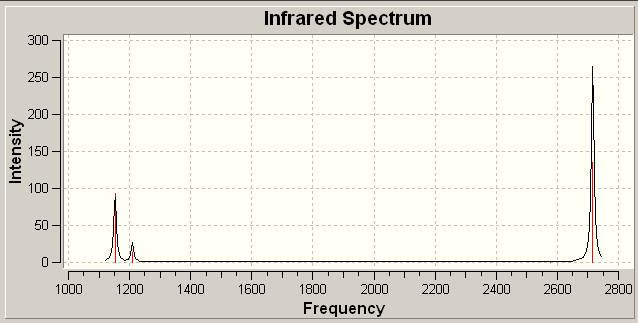

Analysis of the IR spectra of BH3 (figure 1) shows that despite the six vibrations, only three peaks are seen. This is firstly because there are two pairs of degenerate vibrations (vibrations 2 and 3 and vibrations 5 and 6); and secondly because vibration 4 has an intensity of 0. The vibration has no intensity because it is a totally symmetric vibration, and therefore, does not result in a change in the total dipole moment.

Figure 1 IR spectrum of optimized, trigonal planar BH3

MO Analysis – BH3

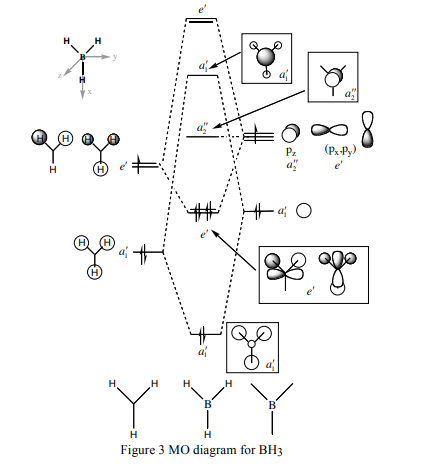

Computer modeling is also able to compute the quantitative molecular orbitals present in a molecule. Below is an MO diagram of trigonal planar BH3, showing the predicted qualitative MOs together with the quantitative ones derived by Gaussian on the optimized structure.

As can be seen all the occupied MOs are extremely similar. Qualitative predictions cannot, of course, predict the exact shape of an orbital resulting from an overlap: for example, in the HOMO, there is overlap of an s and p orbital, which is somewhat rounder than the predicted qualitative version. It is, however, obvious that the overlap seen is the same as that predicted. This can show MO theory is sufficiently accurate for the prediction of bonding orbital shape.

The case is slightly different for the unoccupied orbitals. The LUMO is the same because it is just the pz orbital of the boron atom but in the LUMO+1, the relative sizes of the B s orbital and three H s orbitals are reversed. One would predict that the B s orbital would be larger because the MO is anti-bonding and the energy of the B s orbital is higher than that of the three bonding H s orbitals. However, the quantitative pictures show it to be smaller. As we move up the unoccupied orbitals, they start to look very different and the e’* orbitals bear very little resemblance at all to the qualitative predictions. These results show up the inaccuracies of qualitative predictions when electrons are not occupying the orbitals, though this is not very surprising as unoccupied orbitals do not exist anyway.

Part 2 - An Organometallic Complex

Geometric Analysis

Computer modeling is a very useful tool in the exploration of the stereo-isomers of a complex because stereo-selectivity in reactions is exceptionally important in the catalytic and pharmaceutical industries. Here, analysis will be carried out on modeled structures of the –cis and –trans isomers of Mo(CO)4(PCH3)2.

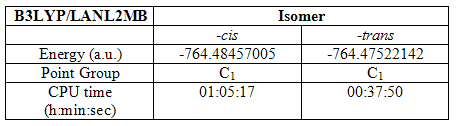

The –cis and -trans isomers of Mo(CO)4(PCH3)2 were created and optimized three times using the B3lyp method and various basis sets. The first used was the LanL2MB basis set. During this optimization, the convergence criteria had to be set loose to prevent the computer attempting to reach a level of accuracy it was unable to do with the basis set in use. This initial optimization provided a structure better prepared for higher optimizations. The results are summarized in the table below:

Table 5

At this point, it can be seen that the –cis isomer is lower in energy by 0.00934a.u. Its optimization also took a little longer.

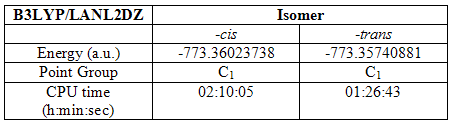

The structures were then optimised again using the better LanL2DZ pseudo-potential and basis set. Here the convergence criteria need not be set loose because this higher level basis set is able to reach the limits set by the normal convergence criteria. The results are summarized as follows:

Table 6

The energies of the two isomers have both dropped quite considerably, showing more energetically stable structures have been made, structures that could not be described by the lower level basis set. Again, the –cis isomer is marginally lower in energy and took a little longer to optimize.

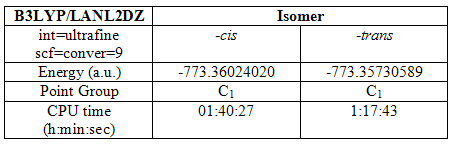

A final optimization was then run. This again used the LanL2DZ basis set. However, this time the electronic convergence was increased (int=ultrafine scf=conver=9) to try and reach a better optimized structure. Initially, it was attempted to use tight convergence criteria in this optimization. However, analysis of the failed calculation proved that this to be too much.

It was seen that the optimization was effectively reached (the potential energy curve was almost straight) but slight displacements in the structure made by the computer were causing a change in energy large enough (small peaks) to reach over a set cut off point and make it think it had not yet reached an optimum. The computer, therefore, continued trying to reach an optimum it was never going to get and the calculation ran for its maximum time (159 attempts) but failed to produce a result. The tight convergence criteria was removed and the optimization repeated.

Table 7

This final optimization lowered the energy of the structures only marginally, though this is expected because the basis set is still the same and it is only the electronic convergence that was increased. These results show that increasing the electronic convergence criteria can help to give a more optimized structure, but in this case, the effect was small. The calculations took less time, though again this is expected because the main bulk of the optimization had all ready been carried out.

Unfortunately, there were problems with publishing the result of the -trans optimisation onto the D-Space. However, its frequency analysis vibration could be published, and therefore, the results of the optimisation can be found there (DOI shown below). The optimixed -cis isomer can be found at DOI:10042/to-1088 .

The results from this final optimization show the –cis isomer to be 7.704kJ/mol (1.8413kcal/mol) lower in energy than the –trans. This is may at first seem a little unexpected: usually the –trans isomer is the lower energy, more stable product because it does not experience the steric repulsions associated with putting bulky substituents cis to each other. However, analysis of the geometry and physical parameters of the structures, with the help of Gaussview, can provide an explanation for the seemingly surprising results.

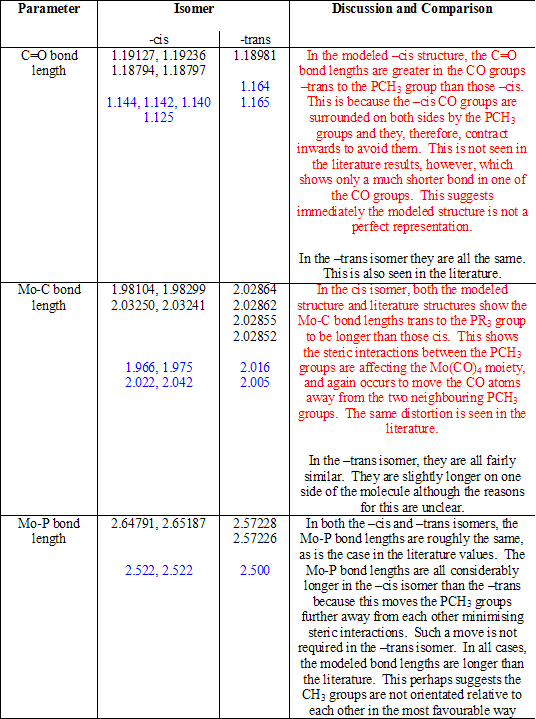

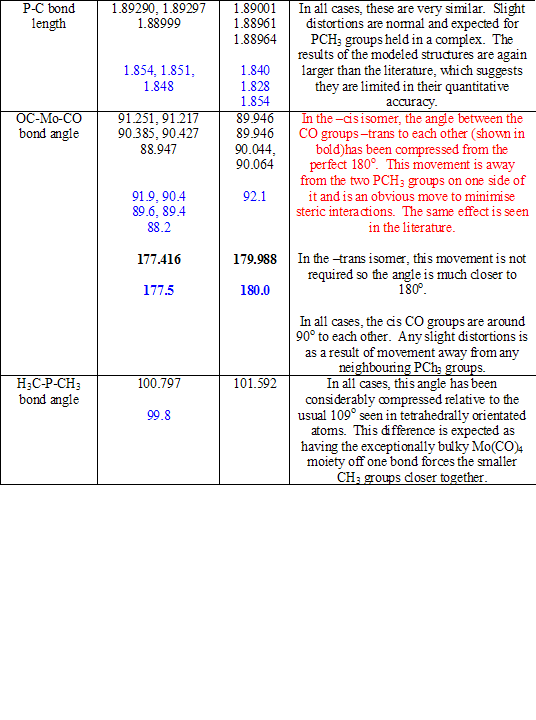

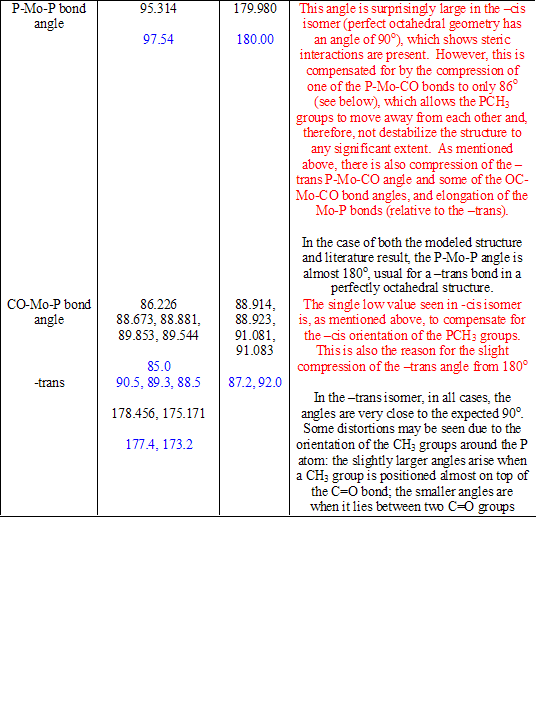

The cone angle of P(CH3)3 is only 118o[1], and so, in this case, the steric repulsions are not great. This means, only slight distortions of the molecular shape are required to accommodate for the repulsion that is present. These distortions can be seen on comparison with the –trans isomer. Table 8 compares the physical parameters of the two structures (and the literature values[1] [2], shown in blue) and explains the results seen. Typing in red discusses only the –cis isomer; typing in black discusses only the –trans isomer or makes comparisons between the two.

Table 8

With such distortions in the –cis structure possible, sterics become less of a factor, and instead the destabilizing effect of having mutually –trans carbonyl groups, as present in the –trans isomer, determines the energy difference between the two. These results mean,therefore, that by altering the size of the ligands, by either changing them completely or adding or removing substituents, the relative energies of the two isomers can be controlled, allowing for their stereo-selective formation.

Vibrational Analysis

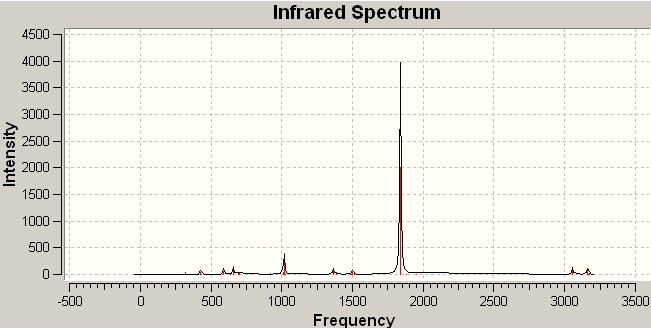

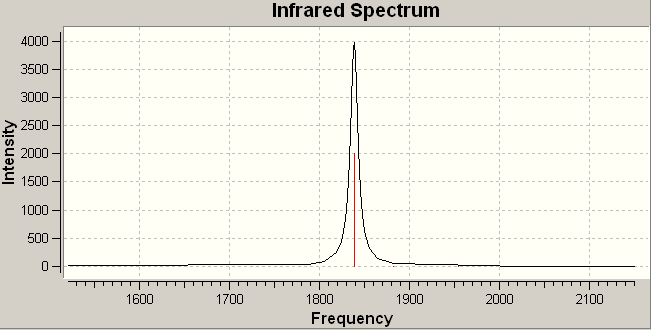

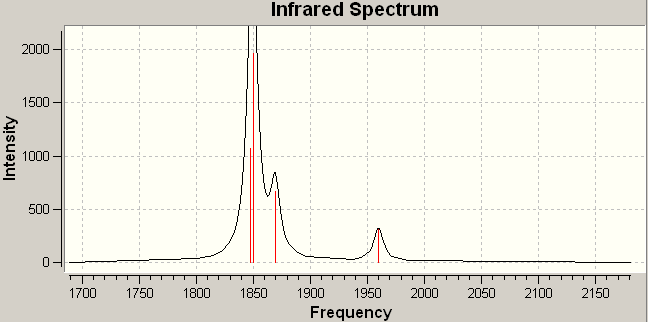

Infrared spectroscopy is an essential technique for isomer identification. In this case, with such large molecules involved, it would be futile to examine all the vibrations present. Instead, obvious differences between the vibrational modes of the two isomers have to be identified, which would result in differences in their IR spectra. In the case of the –cis and –trans isomers of Mo(CO)4(PCH3)2, this is the C=O bond vibrations. In the –cis isomer, four C=O vibrations will be seen; in the –trans, only one will be seen. Reasons for this are explained below.

Unfortunately, despite the full optimizations, the results from the IR spectra showed the –trans isomer to be a transition state, giving two negative frequencies. The calculations were repeated but the same result was obtained and the reasons for it could not be determined. There was not time to investigate the problem further. Therefore, the actual values for the vibrations in the –trans isomer may not be particularly accurate. However, the important features of the vibrational modes and the IR spectra can still be used to examine the differences between the two.

The IR spectra of the two isomers are shown below, together with an enlarged image of the peak(s) corresponding to the C=O vibrations. It can be seen from the spectra, that in agreement with expected results, the spectra of the –cis isomer contains four peaks. The spectra of the –trans isomer shows one. In fact, if considerale zoom is applied, two peaks are seen but the vibrations corresponding to these peaks should be degenerate: they correspond to the Eu asymmetric stretching of 2 –trans carbonyl groups. However, they do only differ by 0.22cm-1, and can be considered to be degenerate. The slight separation between them will be a result of the unsuccessful optimization, and will, therefore, be ignored.

There were again problems with publishing the frequency analysis of the -cis isomer. The publication of the -trans isomer was, however, successful and can be found at DOI:10042/to-1087 .

Figure 3

Analysis of the vibration frequencies gives a more detailed picture. In the –cis isomer, there are four different vibrations, each with a considerable intensity, all of which will be seen in a plotted spectra. The –trans isomer also has four vibrations. However, only one peak is seen because two are degenerate (almost) and two have no intensity (almost). These vibrations have no intensity because they do not cause a change in the total dipole moment of the molecule. This is a result of the higher symmetry of the –trans structure, and is the same effect as that seen with the all symmetric vibration in trigonal planar BH3.

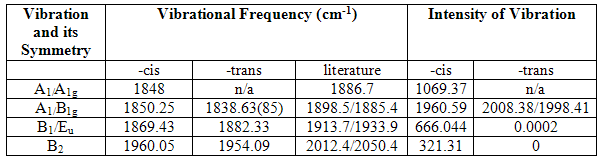

In the table below, the frequencies of the C=O groups in the two isomers have been shown, together with the literature values[1] [3], (note the literature values for the –trans isomer are of Mo(CO)4(PnBu3)2, and so there will be some differences. The point group of the –trans isomer is taken as D4h and that of the –cis is C2v.

Table 9

In all cases, the vibrations are considerably higher than the literature results and it is considered that this is again a result of the imperfect optimization.

There are other frequencies that provide interesting analysis and show a similar picture. In the –trans isomer there are four Mo-C bond vibrations: the all symmetric stretch in and out, the symmetric stretch of two–trans bonds occurring asymmetrically to the other pair, and the degenerate pair of asymmetric stretching of two –trans bonds. However, only one peak is seen on the spectrum because the all symmetric vibration and –trans symmetric vibrations have zero intensity and the other two are degenerate. The –cis isomer also has four Mo-C vibrations: two –cis bonds vibrating together symmetrically, two cis bonds vibrating together assymetrically, two –trans bond vibrating together symmetrically and two –trans bonds vibrating together asymmetrically. In this case, although the intensities are much lower because the change in dipole moment is much less, all are seen on the IR spectrum.

Part 3 - Ammonia

Symmetry Analysis

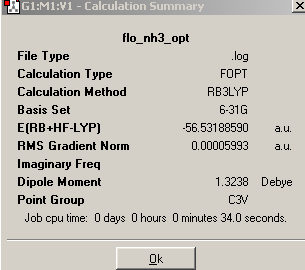

A simple molecule of NH3 was created and optimized by Gaussian using a B3Lyp method and 6-31G basis set. The summary output of the resulting molecule appears as follows. It has a C3v point group because it is pyramidal and therefore does not have 3C2 axes or a σ plane of symmetry:

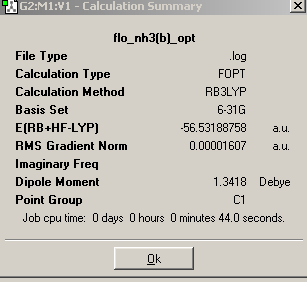

On lengthening one of the N-H bonds, the C3 rotational axis is removed and a C1 point group is created.

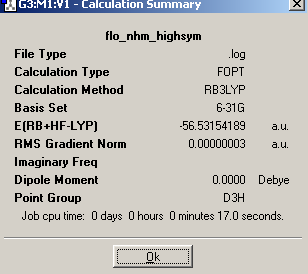

On forcing the molecule to adopt a planar structure, the C3 rotational symmetry is replaced and 3C2 axes and a σh plane of symmetry are now present. The point group becomes D3h.

On analysis of the time it took to make the calculations, it is clear that the higher the symmetry of the molecule, the faster the calculation. This means that when possible, a molecule should be ‘symmetrized’ previous to optimization, if calculation times are to be reduced. Higher symmetry structures require less time to optimize because they have a larger number of equal parameters, and so fewer calculations must be made. For example, in the D3h structure, the affect of changing bond length on the potential energy, need be calculated only once because it can then be multiplied accordingly to obtain the final energy. In the C1, structure on the other hand, two calculations must be made, one for the two short bonds, and one for the single long bond.

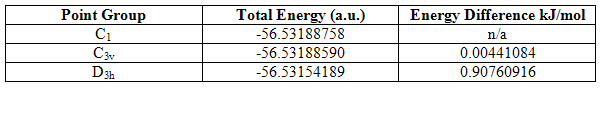

The energies of the three structures are shown below, together with the energy difference between the lowest energy structure and the other two. The lowest energy geometry was that of the pyramidal C1 molecule.

Table 10

It can be seen that higher symmetry structures have higher energy, and the difference between the C1 and C3v structures is much less than that between the C1 and D3h structures. The D3h structure is higher in energy because it has ignored the presence of the nitrogen lone pair and compressed three occupied orbitals very close together. This results in high electron repulsions. The C1 is marginally lower in energy than the C3v perhaps because longer and unequal bond lengths have reduced electron repulsions. However, the energy difference between all the structures is not large enough to be significant because both are much less than kBT (2.4768kJ/mol), and therefore, at room temperature, there is sufficient energy input for the inter-conversion between the three. This is especially the case for the C1 and C3v structures.

On reading the intermediate geometries of the optimizations, it is clear that the molecules did not ‘break symmetry’ during the optimizations. The implications of this are that optimizations of high symmetry structures will be considerably better and more accurate (more alike the real thing). Their energies and bond lengths etc. will also be more realistic.

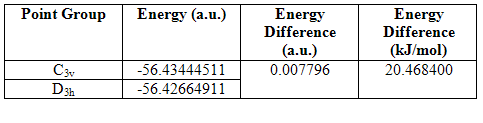

Method Analysis

If higher levels methods and basis sets are used to optimize the different structures of NH3 the calculations as expected take longer, although with such a small molecule, the difference is marginal. Time restraints associated with increasing the basis set size only become a factor with much larger molecules containing heavier atoms. A higher level optimization (MP2 method/6-311+G(d,p) basis set) was carried out on the two NH3 structures. The D3h calculation took 39 seconds longer. The C3v took over 7 minutes longer. (However, this calculation was run when the laptop was being very slow and is not considered an accurate result for use in this comparison.)

Table 11

These results show the energies of both structures having increased by about 0.1 a.u. (262.6kJ/mol), which is quite a substantial amount. However, as different optimization methods are used, comparison between the results is not applicable.

It can also be seen, however, that the energy difference between the two structures is now much larger, way above kBT at room temperature. The energy barrier for interconversion between the C3v and D3h structures following the higher level optimizations is calculated as 20.5kJ/mol (3s.f.). This is a little less than the actual value of 24.3kJ/mol, which shows that even these higher levels are not yet good enough to give very accurate results. However, the H-N-H bond angle is 107.5o, which is very close to the actual angle present in gaseous ammonia (107.3o) and the N-H bond length is exactly the same (1.01Ǻ). This does show that the higher level basis sets have much better described the actual structure and its properties.

Inversion Mechanism and Vibrational Analysis

Obtaining information about the energy differences between these two structures has provided important information regarding the activation energy of the inversion mechanism: the D3h structure is the transition state for this mechanism.

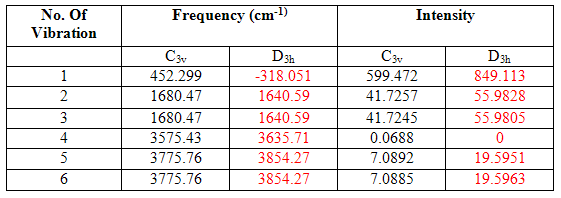

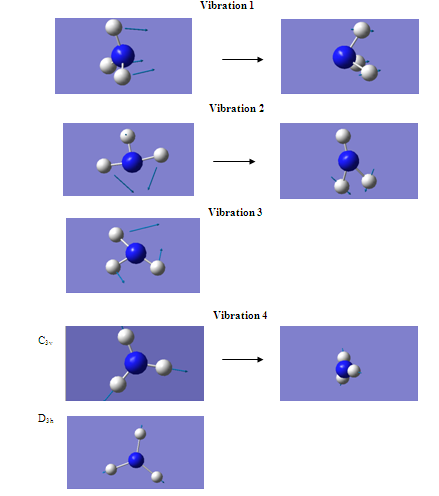

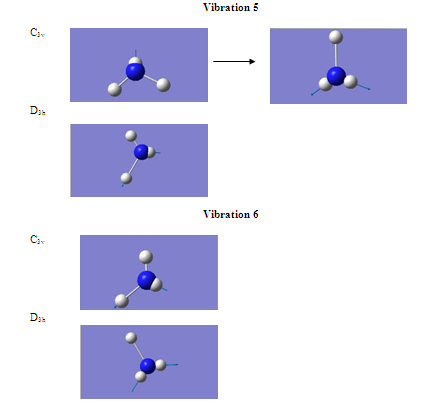

The vibrational modes and their associated energies of the two structures are shown in the table below, and diagrams of the vibrations and IR spectra follow:

Table 12

It can be seen from the table above that the C3v structure has six positive vibrations, whereas the D3h has five positive and one negative. Vibration 1, which is the negative vibration for the D3h structure, involves the movement from the C3v structure, through the D3h structure, and then back to a reflected C3v. As mentioned above, the D3h structure is, therefore, a transition state of that vibration.

Another difference between the two is that the character of motion of vibrations 5 and 6 have been reversed in the two structures. However, these two vibrations are degenerate, and the intensities are almost exactly the same and so the number given to the vibration becomes arbitrary??

Figure 4

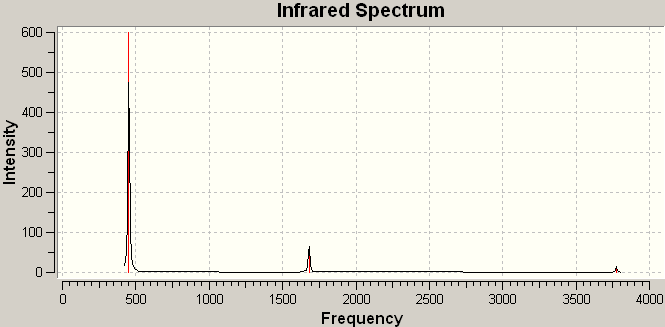

IR Spectrum of C3v structure

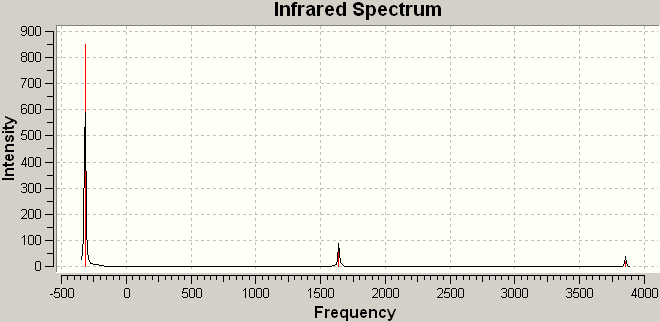

IR Spectrum of D3h structure

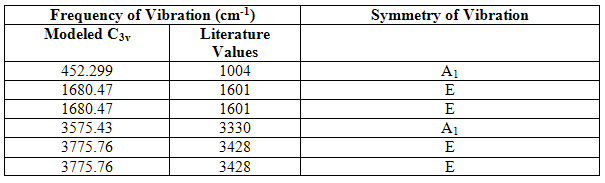

The vibrations of the C3v structure can be compared with literature results[4] to provide another indication of the degree of optimization of the structure and the geometric similarity of it to the actual molecule. The table below compares them:

Table 13

It can be seen from these results that there are alarming differences between the modeled results and literature results. The most substantial difference is between the results of vibration 1, the vibration mimicking the inversion mechanism, of which the modeled results are less than half that of the literature. However, it must be remembered that the structures used for the prediction of the vibrational modes were only optimized by the lower level B3lyp/6-31g method and basis set, and in these structures, the bond angles were much greater than those actually present in gaseous ammonia and the bond lengths a little shorter. A larger H-N-H bond angle will lower the energy of the vibration following the inversion reaction path and shorter bond lengths will explain why all the bond stretching vibrations (2-5) are of higher energy than those in the literature. This further emphasizes the importance of using high level optimizations if accurate results are to be obtained.

Mini-Project - The Fascinating Analysis of Structure, Redox Chemistry and Aromaticity in Rare Types of Boron-Containing Porphyrins and Isophlorins

Introduction

Research into transition metal porphyrin complexes has been long and extensive. This is primarily due to their huge significance and roles within biological systems: haemoglobin, for example, contains an iron-complexed porphyrin. The chemistry of main group porphyrins has not been so widely explored and any significant contributions to their study have only occurred much later.

However, over recent years, interest in these fascinating structures has been increased and current research into boron containing porphyrin complexes, (largely carried out be P.J. Brothers et al[5] [6]), ), has now allowed for the full characterisations of a number of their geometries and structural types. Boron containing porphyrins were of particular interest because they were different in having two atoms in the centre of the ring, rather than the usual one. The steric confinements associated with this resulted in unusual boron chemistry and it meant tetrahedral or trigonal planar geometry had to be adopted rather than the square planar or octahedral geometries usually seen in porphyrin complexes.

Two examples of boron-porphyrins, adopting trigonal planar geometries, are the exceptionally unstable, yet isolable, neutral complex [B2(por)], the initial characterisation of which was only carried out last year, and its oxidised counterpart [B2(por)]2+. In their work in 2007, P.J. Brother et al.[5] sythensised [B2(por)]2+ by the removal of chloride ions from the complex [(BCl)2(por)]. With the reaction conditions they used, the cationic complex was formed as the extremely air and moisture sensitive salt [B2(ttp)]2+[B(ArF)4]2-. It was found, and as shall be shown in this report, that [B2(por)]2+ contains two three-coordinate, trigonal planar boron(II) atoms, held together by a B-B single bond, and an aromatic 18 π-electron porphyrin ligand.

It was known that [(BCl)2(por)] similarly contained boron(II) and a B-B single bond. [(BCl)2(por)], itself, had been formed by a two electron reduction of [(BCl2)2(por)], a complex containing boron(III). It was proposed, therefore, that a further two electron reduction of [(BCl)2(por)] may form the neutral complex [B)2(por)], formally containing boron(I) and perhaps, a B=B double bond.

However, there was an alternative. In forming the neutral complex [B2(por)], there may also be the reduction of the porphyrin ligand, which would leave the boron atoms with a formal charge of (II) and instead form the 20 π-electron isophlorin tetraanion. It was clear that comparison with the [B2(por)]2+ complex, which is known to contain boron(II) and an aromatic porphyrin ring would provide an indication of which was formed.

An 18 π-electron porphyrin ligand has been determined to be aromatic by fulfilling all criteria of Huckel’s rules for aromaticity: it is planar, cyclic and has 4n+2 π-electrons (n=4) if a certain route around the ring is taken. NMR analysis of the 18 π-electron porphyrin dianion present in [B2(por)]2+ together with the complex itself will, and does, prove it to be aromatic (see Results and Discussion section for further details). The 20 π-electron isophlorin tetraanion, on the other hand has 4n (n=5) electrons and therefore fulfils criteria for Huckel anti-aromaticity. If the neutral [B2(por)] complex contains the reduced 20 π-electron isophlorin ligand, rather than the reduced boron(I), its NMR should appear very different and analysis should lead to the conclusion anti-aromaticity is present. Computer optimisation and NMR analysis has been carried out to provide the data required for this comparison.

In addition to this, MO theory and the calculated MOs of the two boron complexes have been used to provide an explanation for the differences in energy, geometry and NMR spectra that are seen. This explanation explores the changes that occur in the FMOs (frontier molecular orbitals) on the addition of two electrons during the reduction of [B2(por)]2+ and formation of its neutral counterpart, [B2(por)]. Their MO energy level diagrams are used to explain the generation of the different ring currents that result in the aromatic or anti-aromatic behaviour (it that is what occurs!) of the two species.

Experimental Details

Initial optimisations were carried out on all four structures at the DFT optimum geometry using the B3lyp method and Gaussian 6-31G basis sets. Second, improved optimisations were then carried out on three of the structures using the LanL2DZ basis sets, and high electronic convergence criteria (scrf=conver=9). It had been taken from the literature(1) that the [B2(por)]2+ complex had the expected, higher symmetry D2h point group, and the neutral [B2(por)], the lower C2h point group. These molecules were therefore symmetrised to these point groups before the second optimisation was run, in an attempt to greatly shorten the time required for the calculation. Unfortunately, the first attempt at optimisation of the 20 π-electron isophlorin tetraanion did not work and it, therefore, had to be run again. This calculation was exceptionally long, and time restrictions prevented a second, improved optimisation from being carried out. Using the additional keywords pop=full, molecular orbitals were generated for all four species, although these were opened and viewed using ChemBio3D ultra and their formatted Gaussian checkpoint files, following failed attempts to save the Gaussian checkpoint files.

Various NMR calculations were run. As the initial aim of the testing was to discover the type of aromaticity in the structures, ghost Bq atoms were used to determine the nature of the ring currents present inside the centre of the porphyrin rings. NMR analysis was carried out using B3lyp/LanL2DZ with no solvent. No solvent is used with Bq ghost atoms, because the computer is unable to calculate the energy associated with forming a cavity around it in the solvent (its radius is 0), and, therefore, the calculation terminates. (This NMR aromaticity analysis could not be carried out on the 20 π-electron isophlorin tetraanion, again, because of time). However, there was also interest in the chemical shifts of the peripheral protons and central nitrogen atoms, all of which will be affected by the different ring currents. Therefore, normal NMR analysis was carried out using a solvent of chloroform and, again, the B3lyp/LanL2DZ method/basis set combination. This was only done on the boron containing complexes.

Results and Discussion

Geometric Parameters

The B3lyp/LanL2DZ (6-31G for tetraanion) optimised structures of the two anions are shown in figure 1 and can also be found at DOI:10042/to-1068 and DOI:10042/to-1067 .

D4hProj18e |

Dianion

Proj20e |

Tetraanion

Figure 1

The 18 π-electron porphyrin dianion shows a planar, high symmtery D4h structure. The 20 π-electron isophlorin tetraaanion shows a much lower C1 structure, implying no rotational or reflection symmetry. This lowering of symmetry is explained later, with reference to the molecular orbitals of the two boron complexes. However, it must also be remembered that this structure is not fully optimised and it appears perfectly planar in the picture, and should, perhaps have a C2 or C2h symmetry instead. The 18 π-electron dianion is shown to be a huge 1843.87kJ/mol lower in energy than the 20 π-electron tetraanion. This will part be a result of the added stability arising from the complete conjugation present in the aromatic 18 π-electron structure, but also of the lower optimisation of the 20 π-electron structure. The distances between the N atoms were shown to be considerably longer in the 20 π-electron tetraanion (3.04855Ǻ compared with 2.97030Ǻ in the dianion).

However, for the purposes of this report, it is more important to examine the structures of the two boron complexes. 3D rotational images of these two structures are shown in figure 2 and can also be found at DOI:10042/to-1069 and DOI:10042/to-1070 .

Chargedboron |

Charged Boron Complex

Neutralboron |

Neutral Boron Complex

Figure 2

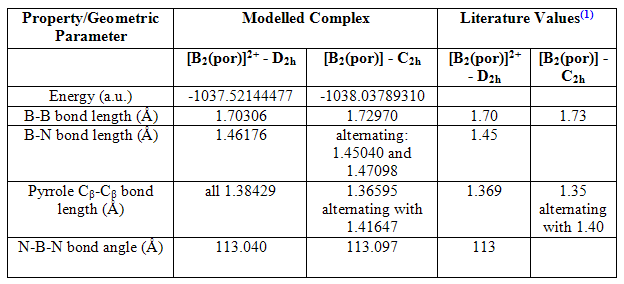

It can be seen that both structures are completely planar, although this is expected because the structures were symmetrised to be this way initially, and both contain two three-coordinate trigonal planar boron atoms. Table 1 shows the energies and some important geometric parameters of the two structures, which allow comparisons to be made.

Table 1

There are many results shown in the table above that lead to the conclusion that the neutral [B2(por)] contains the 20 π-electron isophlorin rather than a B=B double bond. Leaving energy aside for the moment, the first important result is the similarity in B-B bond length between the two structures. If in the neutral complex, a B=B bond were present, it would be considerably shorter than the B-B single bond present in the 18 π-electron [B2(por)]2+. It is, in fact, longer. The N-B-N bond angle is also very similar, and one would expect this to change if the B-B bond became double. It was this bond angle of ~113o that allowed researchers to conclude that trigonal planar boron atoms were present in the two complexes, because it is much greater than the 105.6o[5] seen in the tetrahedrally orientated boron of the starting material in their formation, [(BCl)2(por)].

In addition to this, there is strong evidence for the presence of anti-aromaticity in the neutral complex with comparison of the pyrrole Cβ-Cβ bond lengths. It can be seen that in the [B2(por)]2+ complex, they are all the same length, which shows all the pyrrole rings are equivalent and there is full delocalisation of the 18 π-electrons. In the neutral complex, on the other hand, they alternate in size, differentiating the neighbouring pyrrole rings. This can provide evidence for Jahn-Teller distortion, which anti-aromatic species are known to sometimes undertake: these distortions occur to remove degeneracy within the complex and result in partially localised π-electrons and alternating bonds. However, as discussed in more detail below, this partial localisation is also due to the effects of adding two electrons into previously unoccupied orbitals.

NMR Analysis

Huckel’s rules define aromaticity and anti-aromaticity by stating certain criteria a structure must possess to allow the two effects to occur in the first place. However, the effects that then arise due to a molecules’ aromaticity or anti-aromaticity can also be used in their definition. One such effect is the nature of the ‘global ring current induced by a perpendicular magnetic field’[7]. When an external magnetic field is applied perpendicular to the plane of an aromatic or anti-aromatic porphyrin ring, currents are induced by the movement of the electrons of the π system, whether they be delocalised or partially localised by distortion. These ring currents are described as either diamagnetic (paired electrons), which weakly repel the external field, or paramagnetic (unpaired electrons), which weakly attract the external field. This differing behaviour under the influence of a field result in ring currents that flow in opposite directions. For reasons discussed later, aromatic species display diamagnetic ring currents and anti-aromatics display paramagnetic ring currents.

This has considerable implications for NMR spectroscopy. For Bq atoms in the centre of the two complexes or hydrogen atoms on the periphery, the opposing directions of the two types of current will impose opposite shielding effects. It is well established that protons on the outside of a large aromatic system are substantially deshielded by the ring current generated and shift a considerable way downfield. Protons on the periphery of an anti-aromatic species will, therefore, experience shielding by the current and display paratmagnetic upfield shifts in their spectrum. It must be noted here that in most anti-aromatic species there is some secondary diamagnetic current, the reasons for which shall be explained later, and therefore, it does not necessarily mean the shift will be negative relative to the reference peak. It will just be shifted a lot further upfield than the aromatic protons.

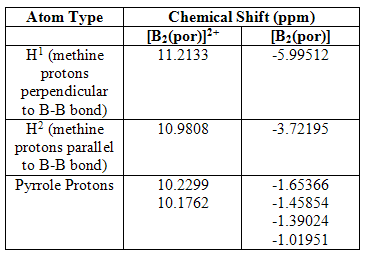

On analysis of the HNMR spectra of the two complexes, it is immediately clear that the [B2(por)]2+ complex is diplaying diamagnetic shifts and the neutral [B2(por)] complex, paramagnetic shifts. This further provides evidence for the presence of the 20 π-electron anti-aromatic porphyrin ligand in the neutral complex. The complete spectra have been published onto D-Space and can be found by the following links DOI:10042/to-1065 and DOI:10042/to-1066 . Table 2 summarises the NMR data.

Table 2

Another important result stemming from this data is the chemical inequivalence of each of the pyrrole protons in the neutral complex. This is again due to the lowered symmetry, following changes in the molecular orbitals.

NMR analysis was also carried out on the 18 π-electron porphyrin dianion and, as expected, there was considerable shifting downfield of all peripheral protons.

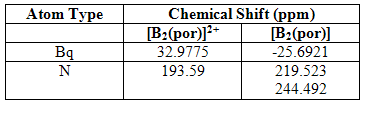

If atoms on the outside of the aromatic ring are deshielded, it follows that atoms on the inside will be shielded and vica versa. The NNMR can support this supposition. Please note, the actual values for the shifts of the NNMR spectrum will be very limited in their accuracy because proper investigation into the most appropriate solvent was not carried out. It is the relationship between the values, however, that is important.

Table 3

The relative shifts of the Bq atom unfortunately did not. (For some unknown and very annoying reason, the Bq spectra could not be published to D-Space. However, figure 3 below shows how the Bq atom was positioned, together with the resulting NMR spectra). It can be seen that the shift of the Bq atom in the charged complex is positive relative to the reference; in the neutral complex, it is negative. This is, of course, the opposite to what was expected. However, as was discovered later, the sign, and therefore direction, of the shift of Bq atoms is actually dependent on what is inputted into the computer and is, therefore, not significant (the details of all this are not known). What is important is that the signs are opposite in the two complexes, which again proves that two opposing currents are flowing.

NeutralBq |

NMR Spectrum of the Charged Boron Complex

NMR Spectrum of the Neutral Boron Complex

Figure 3

There are, however, still problems associated with the calculation that was carried out. The first, and most serious, is that the Bq atom had to be placed very close to both boron atoms. This means of course, that the shielding experienced by the Bq atom will be massively affected by the electrons of the boron atoms, unfortunately rendering the quantitative aspect of the results meaningless. Bq atom testing is only really applicable if it can be placed a considerable distance from any atoms. (In the literature, the Bq atom was placed in the centres of the pyrrole rings.) The second problem is that the Bq atom was placed on the same plane as the atoms of the complex being examined. It will, therefore, be affected by the fairly strong σ-electron ring currents that are induced there. More accurate results would be obtained if the Bq atom was placed slightly above the plane of the complex, where σ-electron ring currents are effectively absent. (In the literature, the Bq atom was placed 1 Ǻ above the atoms).

NMR Explanation by MO Theory

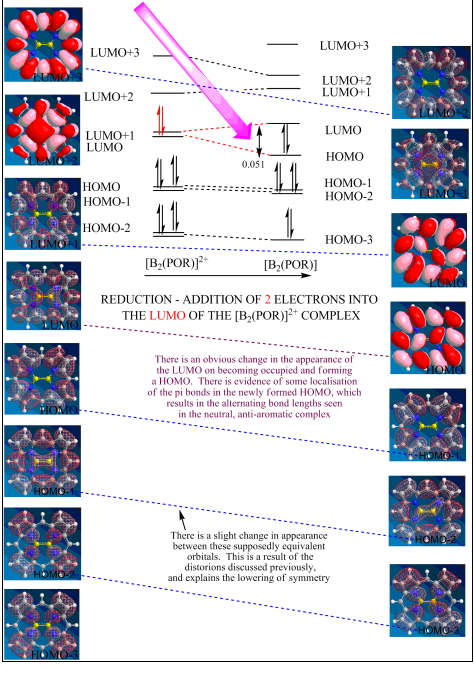

As has been seen, computational analysis has led to the conclusion that the neutral [B2(por)] complex is formed by the two electron reduction of the porphyrin ligand, and thus contains an anti-aromatic 20 π-electron isophlorin tetraanion species. The oxidised [B2(por)]2+ form is 18 π-electron aromatic. It has also been seen that the anti-aromatic property of the neutral complex has led to paramagnetic ring currents being generated around the ring. The molecular orbitals generated in optimising the [B2(por)]2+ and [B2(por)] complexes are now to be analysed in an attempt to provide an explanation as to why the paramagnetic or diamagnetic currents are seen. Fortunately, it was discovered by E. Steiner and P. Fowler in 2002[8], that despite the considerable size and complexity of the porphyrin ring, it is only the HOMO-1 and HOMO frontier orbitals that make any significant contribution to the ring currents that are generated. This makes the job at hand a lot easier!

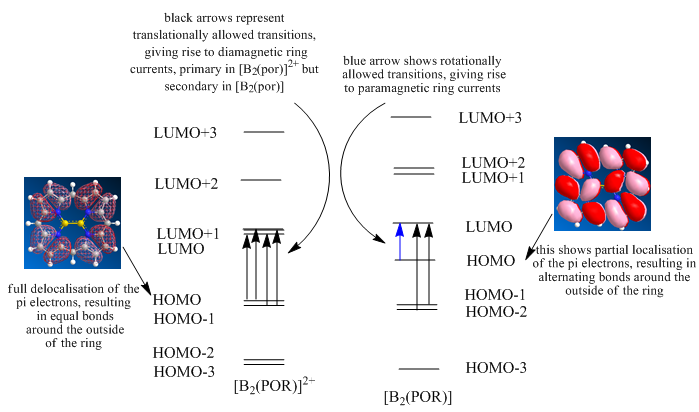

Figure 4 below shows the relative energy levels, drawn roughly to scale, of the frontier orbitals of the [B2(por)]2+ complex, together with the splitting that would occur on adding two electrons to from the neutral [B2(por)]. Shown, also, are pictures of the molecular orbitals to which the energy levels correspond. The text explains the significance of what is seen.

On forming the neutral complex, it can be seen that the LUMO of the cationic complex has now been occupied, thus becoming the HOMO of the neutral complex. This has lowered its energy relative to the previously almost degenerate LUMO+1 orbital, resulting in a splitting (0.051 relative energy units: it is this split that causes the geometric distortion and lowering of symmetry), which as shall be seen, has very important consequences. As the splitting energy is not large, the new HOMO has not reached below the previous HOMO and therefore, there is a simple shift downwards of both the HOMOs (HOMO becomes HOMO-1, HOMO-1 becomes HOMO-2 etc.) and the LUMOs (LUMO+1 becomes LUMO, LUMO+2 becomes LUMO+1 etc.). The dashed lines, shown in black between levels on the energy level diagram and blue (where possible) between pictures, represent this by linking the equivalent orbitals in the two complexes. The equivalence of the orbitals could be determined by their appearances, which are shown in the pictures down the side.

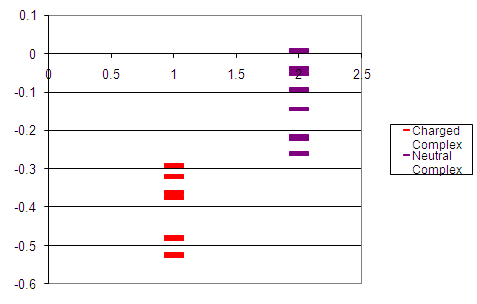

Figure 4

For clarity reasons, figure 4 shows the two energy level diagrams next to each other. In reality, the energy levels of the anti-aromatic structure are considerably higher than those of the aromatic structure, an effect resulting from putting electrons into a high energy anti-bonding orbital. Figure 5 contains an accurate plot of the energy values calculated for the two complexes. The y-axis is relative energy; the x-axis is meaningless. This is, however, just for interest purposes and does not lend significance to the explanation.

Figure 5

As explained by Steiner and Fowler[8], the contribution of an occupied orbital to the generation of ring currents is determined ‘wholly by the accessibility of the unoccupied orbitals by rotational and translational transitions’. Translational transitions are conditional on the electric dipole moment selection rule and are only allowed when there is a change in angular momentum quantum number (Laporte selection rule); rotational transitions are conditional on the magnetic dipole moment selection rule and are only allowed when the angular momentum quantum number remains the same. For reasons discussed later, translational transitions lead to diamagnetic currents and rotational transitions lead to paramagnetic shifts. This is where the generated orbitals and their symmetries and energies become very important.

The HOMO of the [B2(por)]2+ has a relative energy of -0.477 and symmetry au. It is almost degenerate with the HOMO-1 orbital of energy -0.481 and symmetry b3u. The LUMO has relative energy -0.375 and symmetry b2g. It is almost degenerate with the LUMO+1, which has energy -0.362 and symmetry b1g. This means, therefore, that translational transitions are allowed from both the HOMO and HOMO-1 to both the LUMO and LUMO+1. The parity changes from u→g. These translational transitions lead to the diamagnetic, aromatic circulations shown to occur.

If a pair of electrons are then put into the LUMO of the [B2(por)]2+ complex, the splitting of the LUMO and LUMO+1 orbitals, as described above, occurs. This also, as has been established, results in a change of point group of the whole complex. These changes generate a new molecular orbital energy level diagram, in which the HOMO now has relative energy -0.144, standing very much alone (0.072 above the HOMO-1), and a symmetry of bg. The LUMO now also has symmetry bg, which forbids translation transitions. Rotational transitions are, however, now allowed (the parity remains the same, g→g), and so paramagnetic, anti-aromatic ring currents circulate. It can also be seen in the diagram that translation transitions can occur between the au HOMO-1 and HOMO-2 orbitals with the bg LUMO orbital, and these secondary transitions are what causes some diamagnetic current to flow and, therefore, less shielding of any periphery protons than might be expected.

An additional point, although this was not fully understood, is that in the energy level diagram of the [B2(por)]2+, transitions from the HOMO can go to either the LUMO or LUMO+1 orbitals, which involves the possible transition of four electrons. This satisfies Huckel’s rules of aromaticity if n is taken as ½. In the neutral complex however, the primary rotational transition is only possible from the HOMO to the LUMO, and so only a two electron transition can occur. This in turn, satisfies Huckel’s rules of anti-aromaticity if n is taken as ½.

The analysis of the transitions discussed above is shown diagrammatically in figure 6, which again places the two molecular orbital energy level diagrams next to each other to allow the differences to be seen.

Figure 6

This, therefore, has used MO theory to provide a possible explanation as to why aromaticity is seen in the oxidised 18 π-electron [B2(por)]2+ complex but anti-aromaticity in the 20 π-electron [B2(por)] complex.

Additional Information and Research

Following initial investigation into the aromaticity of these porphyrins, it was discovered that Si( was another example of an anti-aromatic porphyrin complex. This structure was optimized and took 59 hours to complete!! It was not, in the end, required, but can be viewed at DOI:10042/to-1104 if interested.

Please see Professor Rzepa for the first ever ELF (pi) isosurface calculations on these two complexes!!! and what they show. It's extremely intresting! Indeed, if I understand correctly, they are the first ever isosurface calculations on any porphyrin containing complex.

I have extremely enjoyed doing this investigation and research project, particularly because, as intended, it allowed for my own independent research and application of theory. It has completely inspired me!! However, I know that I am not very good at expressing myself, so if you ever do not quite understand what I am trying to say, please ask me because I am very keen for you to be able to do so.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Inorg. Chem, 1982, 21, 2661-2666 - F. Cotton, D. Darensbourg et al. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "cisref1" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Inorganica Chimica Acta, 1997, 254, 167-171 - G. Hogarth and T. Norman

- ↑ IInorganic Chemistry, 1979, Vol. 18, No.1 - D. Darensbourg

- ↑ Physical Review B, 2006, 73 155413 - M. Preuss and F. Bechstedt

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Chem. Eur. J. 2007, 13, 5982-5993 - A. Weiss, P. J. Brothers, M. Hodgson, P. Boyd and W. Siebert Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "boron1" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Chem. Commun. 2008, 2090-2109 - P. J. Brothers

- ↑ Org. Biomol. Chem. 2004, 2, 34-37 - E. Steiner and P. Fowler

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 ChemPhysChem, 2002, No. 1 - E. Steiner and P. Fowler