Rep:Mod:LS1109

Luke Squire-Smith Computational Lab

The Hydrogenation of a Cyclopentadiene Dimer

Cyclopentadiene has an important role in organometallic chemistry due to its variable hapticity as a ligand, with its most notable use in metallocenes. One such example is ferrocene, whose yield when synthesised, is often limited by the dimerisation of the cyclopentadiene.

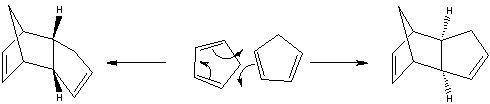

Cyclopentadiene readily dimerises via a 4πS + 2πS cycloaddition reaction (Diels Alder) to form dicyclopentadiene. This dimer has an endo and exo form, of which it is reported that the kinetic, endo product is preferred[1].

Molecular Modelling (MM2 force-field) was used to determine the relative stabilities of compounds 1/2 and 3/4 (below) by optimising their geometries. Bond strain, through torsion energies & dihedral angles (compounds 1 & 2), and bend energies & bond angles (compounds 3 & 4) were calculated.

MM2 and Merck's more advanced MMFF94 are primitive modelling techniques derived from known computational data. Regardless they are able to display suprising accuracy in optimising geometry and Van der Waals forces, but do not take molecular orbital effects and bond conjugation into account. The Semi-empirical PM6 is useful for its accuracy in Hydrogen bonding and ability to take bond conjugation into account. It is best used as a compliment to MM2 & MMFF94.

The results from MM2 optimisation displayed in the table below:

| Compound | Stretch kcalmol-1 | Bend kcalmol-1 | Stretch-bend kcalmol-1 | Torsion kcalmol-1 | 1,4-VDW kcalmol-1 | Dipole/dipole kcalmol-1 | Total Energy kcalmol-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.29 | 20.6 | -0.838 | 7.66 | 4.23 | 0.378 | 31.9 |

| 2 | 1.25 | 20.8 | -0.836 | 9.51 | 4.32 | 0.448 | 34.0 |

| 3 | 1.25 | 19.2 | -0.835 | 11.0 | 5.80 | 0.162 | 35.0 |

| 4 | 1.10 | 14.5 | -0.549 | 12.5 | 4.51 | 0.141 | 31.1 |

Figure 1: A table comparing energies of the exo and endo dimers, and the hydrogenated endo products 3 & 4

| Cyclopentadiene Exo Dimer | Cyclopentadiene Endo Dimer | Product 3 | Product 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Dihedral Angle 179o |

Dihedral Angle 46o |

Bond Angle 108o |

Bond Angle 112o |

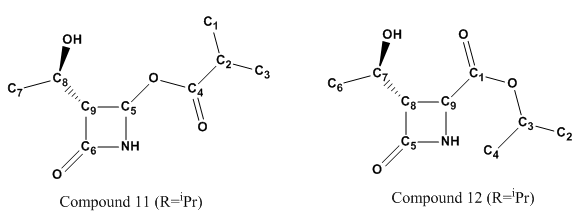

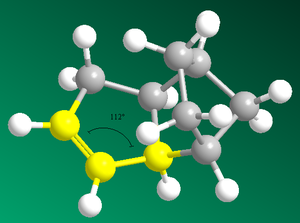

Figure 2: The dihedral angles of the exo & endo products and the bond angles of products 3 & 4

The exo dimer (1) is more stable thermodynamic product by 2.1kcalmol-1.

The exo Dimer (1) has a lower torsion energy (is less strained) (7.66kcalmol-1) and lower overall energy (31.9kcalmol-1) than the endo dimer (2) (9.51kcalmol-1 and 34.0kcalmol-1 respectively). The torsion energy of atoms in a 1,4 relationship is the main contribution to the difference in energy between the dimers.

This idea is demonstrated through analysis of dihedral angles (highlighted above) in both molecules: The dihedral angle of (1) (179o) is representative of an antiperiplanar conformation, which exhibits minimal steric strain. The dihedral angle of (2) (46o) may be described as a mix between an eclipsed and gauche confomer which is strained (and higher in energy) relative to the antiperiplanar confomer[2]. This difference in torsion energy may be attributed to the different symmetries of the molecules.

Because the endo product is known to predominate in this reaction, it is assumed the reaction is kinetically controlled as the higher-energy product (with a more stabilised transition state) predominates. The extra stability of the endo transition state (leading to a smaller activation energy) cannot be explained with MM2 but through frontier molecular orbital theory:

The endo approach (shown right) allows for a greater stabilisation of the transition state than the exo approach through secondary orbital interactions (red dashed-lines) between the HOMO & LUMO of the reacting molecules. A greater overlap (and hence stabilisation) is achieved through the endo approach.

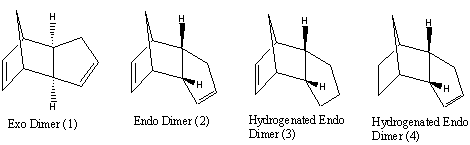

Hydrogenation of the endo cyclopentadiene dimer

Product 4 is the thermodynamic product (31.15kcalmol-1) and was shown to have a lower overall energy than product 3 (35.0kcalmol-1). This difference in energy may be attributed to angular strain:

Analysis of bend energies in hydrogenated products 3 & 4 reveals a greater bend energy in product 3 (19.2kcalmol-1 versus 14.5kcalmol-1). This analysis is backed-up with analysis of sp2 bond angles in products 3 & 4. Product 3 has a smaller bond angle (108o) than product 4 (112o). This is due to the unsaturation in (3) being closer to the bridge than in (4). An ideal C-C sp2 bond angle is 120o. The larger bond angle in (4) therefore rightly reveals a less strained conformation. Further to this, the Van Der Waals energies of product 4 are lower than those of product 3.

It is not known whether the hydrogenation reaction is under kinetic or thermodynamic control. Therefore, although we know product 4 is the thermodynamic product, this does not mean that it is also the kinetic product - this fact cannot be determined from the information available. If the orbitals involved in the hydrogenation reaction were considered, the nature of the transition state could be modelled.

Modelling of the transition state would be required to determine if the hydrogenation reaction is under thermodynamic or kinetic control. This is not possible with Molecular Mechanics and requires consideration of frontier molecular orbitals.

Taxol Intermediates

Reactivity of Taxol Intermediates

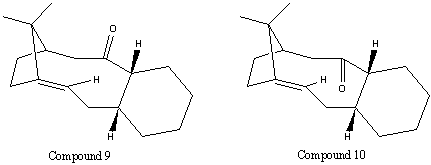

Two potential Taxol synthesis intermediates ( ) were analysed using MM2 & PM6. These intermediates are atropisomers - their isomerism is caused by steric hindrance and hyperstability imposed by the positioning of an olefinic bond at a bridgehead. A molecule with atropisomers, must, by definition, have two (or more) low-lying minima in its energy curve, which cannot be escaped from readily.

Atropisomerism in this case arises from a significant kinetic barrier for rotation of bonds, induced by sterics. For these specific atropisomers, this allows for two 'fixed' orientations of the carbonyl group - one pointing up, and one pointing down. Additionally, the cyclohexane ring in both atropisomers may be either in the chair confomer or the higher-energy twist-boat confomer.

It was reported that the initial compound formed isomerised to the alternative isomer, suggesting the initial formation of the kinetic product, followed by conversion of this atropisomer into the thermodynamic product[3]. It was concluded from the results below that compound 10 was the more thermodynamically stable atropisomer. Due to the reversible nature of the Oxy-Cope rearrangement (which the interconversion of the atropisomers proceeds by), when left to settle, compound 9 would be converted to the thermodynamic product - 10.

MM2 & MMFF94 Calculations

For the purposes of this analysis, we will assume that although theoretically possible, the twist-boat confomers (which are higher-energy confomers) are too high in energy to exist in appreciable amounts in the mixture, and will therefore be discounted. When calculated using MM2 force-field, their energies were 53.3kcalmol-1 (9) and 47.1kcalmol-1 (10) - much higher in energy than the chair conformations (47.8kcalmol-1 and 41.4kcalmol-1 respectively). When calculated using MMFF94 their energies were 76.3kcalmol-1 (9 (twist boat)) and 66.7kcalmol-1 (10 (twist boat)).

| Chair Compound 9 (minimised to 47.8kcalmol-1 (3 s.f.)) | Chair Compound 10 (minimised to 41.4kcalmol-1 (3 s.f.)) |

|---|---|

|

|

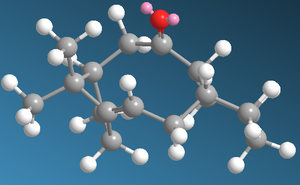

Figure 3: Intermediates 9 & 10 (atropisomers), showing the different orientations of the carbonyl group.

| Compound | Stretch kcalmol-1 | Bend kcalmol-1 | Stretch-bend kcalmol-1 | Torsion kcalmol-1 | 1,4-VDW kcalmol-1 | Dipole/dipole kcalmol-1 | Total Energy (MM2) kcalmol-1 | Total Energy (MMFF94) kcalmol-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intermediate 9 [chair] | 2.95 | 17.2 | -0.501 | 21.3 | 14.5 | -1.73 | 47.8 | 70.5 |

| Intermediate 10 [chair] | 2.78 | 16.5 | -0.430 | 18.3 | 13.1 | -1.72 | 41.4 | 61.2 |

| Hydrogenated 10 | 2.62 | 11.9 | -0.544 | 22.0 | 15.4 | -1.73 | 47.9 | 70.3 |

Figure 4: A table comparing energies of the intermediates 9 & 10, and the hydrogenated product of intermediate 10.

Both optimisation methods (MM2 & MMFF94) determined intermediate 10 to be the thermodynamic product, although the relative stability differences in the force field models cannot be compared due to their use of different parameters to optimise geometry.

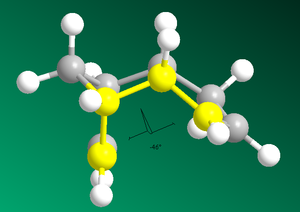

The positioning of the olefinic bond at the bridgehead results in a hyperstable alkene (where olefinic strain energies are negative relative to their saturated derivatives). The abnormally slow functionalisation of this bond may therefore be attributed to the increase in steric strain and overall energy of the molecule from the loss of hyperstability[4] (cf. Figure 4) - although bond formation is energetically favourable, this lowering of energy is more than offset by the loss of the hyperstable olefinic bond.

Olefinic strain energies may be calculated as follows:

Olefinic Strain Energy = Total Energy of Olefin - Total Energy of Saturated Derivative

Under MM2 force field optimisation, the olefinic strain energy of intermediate 10 relative to its hydrogenated derivative is -9.1kcalmol-1. The main contributions to this difference can be attributed to relative differences in Torsion and Van der Waals energies.

Considering the ideal bonding angles of an sp2 carbon as 120o and an sp3 carbon as 109.5o, when analysing the bonding angles of these carbons in compound 10 and its saturated derivative (cf. Figure 5), it is easy to identify the source of hyperstability. In compound 10, the bonding angle is almost ideal at 122o, but in the saturated derivative, a deviation of 5.5o is far from ideal and is the source of the extra torsional strain.

The increase in torsional strain associated with saturation of the olefinic bridgehead and a decrease in stability of the molecule discourages functionalisation of this olefinic bond with electrophiles (e.g. Hydrogenation).

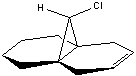

Moreover, the extra stability that an olefinic bond at the bridgehead achieves can also be attributed to a difference between the molecules in Van der Waals energies: Interactions between H atoms at distances ≤2.1Å are repulsive. This relationship is described by the Lennard-Jones 12,6 potential. For the hydrogenated derivative there were 3 such repulsive interactions (1.94Å, 1.94Å and 2.11Å). For compound 10, there was only one repulsive interaction (2.07Å) (cf. Figure 5).

Figure 5: A depiction of the bonding angles and repulsive H-H interactions of compound 10 (sp2) and its saturated form (sp3).

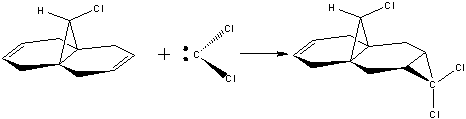

Modelling Using Semi-empirical Molecular Orbital Theory

By predicting the geometry of compound 12 (below), and calculating the energy and shape of its molecular orbitals, its reaction with electrophiles such as dichlorocarbene can be analysed from a theoretical point of view: The reaction with dichlorocarbene (via a [1+2] cycloaddition) forms a mixture of products, with the syn trichloride reported to be the major product (72%) (the disubstituted product the other significant adduct at 23%). PM6 modelling was used although PM3 and RM1 were also trialled and were found to work equally well.[5] [6].

| HOMO -1 | HOMO | LUMO | LUMO + 1 | LUMO + 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

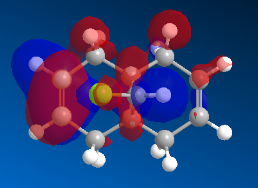

Figure 6: Molecular orbitals of compound 12

From the MOPAC/PM6 calculations of the frontier molecular orbitals, it is clear from the HOMO that the syn olefinic bond will be the most reactive towards electrophillic attack, and from the LUMO it is clear that the anti olefinic bond will be the most reactive towards nucleophillic attack.

In the HOMO, a large proportion of electron density is at the syn π-bond (some electron density is located at the σ-bond of the anti C=C bond, but none in the anti π-bond). In the LUMO, a large proportion of the electron density in the molecular orbital would be found at the π-antibonding anti C=C bond .

It can therefore be concluded that addition of dichlorocarbene, a strong electrophile, will occur at the syn π-bond, and that experimental data on the reaction is well predicted through this modelling.

Additionally, analysis of the HOMO-1 shows a large amount of electron density on the anti C=C π-bond. This suggests that an approach by :CCl2 to the anti C=C bond would not provide as favourable Frontier Molecular Orbital interactions because the energy mismatch between the orbitals would be larger (due to the lower energy of HOMO-1 vs. HOMO).

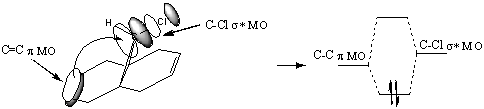

The anti C=C π-bond's increased stability with respect to the syn C=C π-bond can be attributed to stabilisation of the bond with the C-Cl σ* bond. The C-Cl σ* bond is close in energy to the C=C π-bond due to the electronegativity of the Cl atom lowering the energy of the σ* bond sufficiently to interact. No such interaction is possible with the syn C=C π-bond due to its position and orientation within the molecule. This explains the unequal electron density distribution of the π-bonds in the HOMO & LUMO and explains the regioselectivity of the reaction of compound 12 with dichlorocarbene:

From the HOMOs of Compound 12 and its anti-monohydrated product, it can be seen that Compound 12 displays Cs symmetry. This symmetry is lost when the olefinic bond anti to the C-Cl bond is functionalised as the hydrogenated ring departs from planarity. This is demonstrated by the loss of the plane of symmetry (red line in (12)) of the HOMO.

| HOMO Compound 12 | HOMO Hydrated Product |

|---|---|

|

|

Figure 7: HOMO of compound 12 and its monohydrated derivative

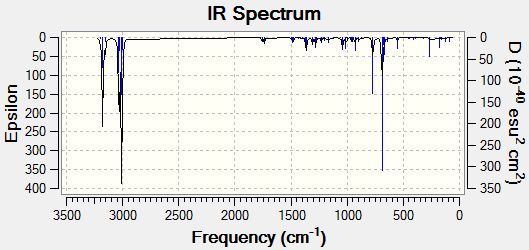

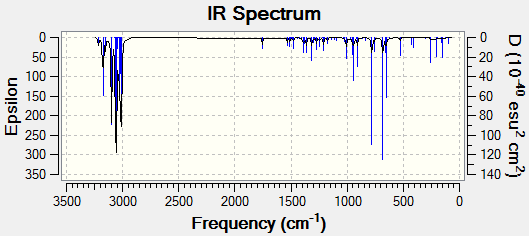

Bond strengths for compound 12 and the anti-monohydrated product (below) were calculated (by comparison of peak vibrational absorption frequencies) through B3LYP/6-31G(d,p)/PM6. Frequency values for the C-Cl and C=C bonds are shown below (cf. Figure 8). Corrected values are also shown (the model is known to overestimate stretching vibrations by ~8%):

| Compound | Symmetry | C=C bond stretch (Syn) [corrected] (cm-1) | C=C bond stretch (Anti) [corrected] (cm-1) | C-Cl bond stretch (cm-1) [corrected] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound 12 | Cs | 1757 [1617] | 1737 [1598] | 771 [709.2] |

| Mono-hydrated product | C1 | 1754 [1613] | N/A | 780 [717] |

Figure 8: Stretching frequencies for Compound 12 and the anti-monohydrated product.

As can be seen from the peak data above. The removal of the olefinic bond anti to the C-Cl bond has increased the wavenumber of the C-Cl bond - the bond has become stronger. This agrees with the statement made above suggesting overlap of the C-Cl σ* bond with the anti C=C π-bond - interaction of these orbitals adds electron density to the C-Cl σ* orbital, weakening it. This concept is backed up by analysis of distances of the olefinic bonds in compound 12 to the bridging carbon. The olefinic bond anti to the C-Cl bond, is closer (3.0Â vs. 3.3Â) (although the sterics of the bulky Cl are thought to also play a part here).

Modelled IR spectra of both compounds are shown below:

| Compound 12 | Mono-hydrogenated Product |

|---|---|

|

|

Figure 9: The calculated IR spectra of Compound 12 and its monohydrated derivative

Here MOPAC/PM6 was an excellent model in predicting the reactivity and regiospeficity of the functionalisation of compound 12 through frontier molecular orbital modelling. This chemistry may have been difficult to rationalise without considering the molecular orbitals of the molecule.

Monosaccharide Chemistry: Glycosidation

It is well understood that due to the neighbouring group effect, glycosylation reactions form the 1,2 trans product almost exclusively (due to neighbouring group effects). However, it is reported that not all glycosylation reactions are 100% stereospecific (there are two confomers of each intermediate (C & C' and D & D'). This theoretically allows for two orientations of attack by a nucleophile per intermediate, and substequently diastereoisomeric glycosidation products from each intermediate.

Figure 10: A reaction scheme showing the routes to producing the alpha and beta anomers through neighbouring group participation.[7]

Methyl groups were used as the 'R' groups when modelling the monosaccharides and their derivatives. Their small electron count compared to an acetyl protecting group (8 electrons versus 19) made them ideal for modelling purposes due to a smaller work load required. Methyl groups also remove hydrogen bonding oppurtunities, which makes molecular geometry optimisation calculations easier. They are better suited to the task than Hydrogen (e.g. OH) for the H-bonding reasons mentioned and 'act more like an acetyl group' than an H atom (in terms of sterics).

Allinger's MM2 method is not particularly useful in optimising the geometries of the isomers as it does not factor in the neighbouring group effects of the acetyl group and the oxonium cation, which are crucial for predicting the regioselectivity of the subsequent formation of the 5-membered oxonium ring. A particular flaw in the MM2 force-field is its failure to take bond conjugation into account. As the acetyl group which attacks is highly conjugated, inaccuracies immediately arise when using this method.

MOPAC/PM6 modelling is superior in this sense and was used to optimise the geometries of A, A', B, B', C, C', D & D'. The differences in geometry of MM2 and PM6 minimised structures were clear. For example, in A & B, the acetyl group adopted 'ideal' 120o angles for MM2, whereas in PM6, the conjugation of the bond and secondary orbital interactions were taken into effect, resulting in the correct 5 membered 'open ring' - the precursor to the oxonium ring (see PM6 Jmols below).

In both modelling methods, A and B were lower in energy than A* and B*

| Compound | Energy (kcalmol-1) [MM2] | Energy (kcalmol-1) [PM6] | Jmol [MM2 optimised] | Jmol [PM6 optimised] | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monosaccharide A | 17.0 | -91.6 | The acetyl group points below the plane of the oxonium cation | ||

| Monosaccharide A* | 30.9 | -77.4 | The acetyl group points above the plane of the oxonium cation | ||

| Monosaccharide B | 20.0 | -88.7 | The acetyl group points above the plane of the oxonium cation | ||

| Monosaccharide B* | 31.2 | -77.5 | The acetyl group points below the plane of the oxonium cation | ||

| Monosaccharide C | 33.3 | -91.7 | The oxonium ring points below the plane of the molecule | ||

| Monosaccharide C* | 46.4 | -62.8 | The oxonium ring points above the plane of the molecule | ||

| Monosaccharide D | 35.7 | -88.5 | The oxonium ring points above the plane of the molecule | ||

| Monosaccharide D* | 43.0 | -67.0 | The oxonium ring points below the plane of the molecule |

Figure 11: A table comparing energies of the monosaccharides A, A*, B, B*, C, C*, D & D* with their PM6 optimised geometries shown in Jmols.

| Compound | Stretch kcalmol-1 | Bend kcalmol-1 | Stretch-bend kcalmol-1 | Torsion kcalmol-1 | Charge/Dipole | 1,4-VDW kcalmol-1 | Dipole/dipole kcalmol-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monosaccharide A | 2.83 | 11.8 | 1.07 | 3.36 | -25.6 | 19.1 | 5.88 |

| Monosaccharide A* | 2.47 | 11.12 | -0.943 | 2.82 | -11.97 | 19.0 | 4.04 |

| Monosaccharide B | 2.67 | 11.6 | 1.01 | 1.61 | -19.33 | 18.3 | 6.18 |

| Monosaccharide B* | 2.37 | 9.67 | 0.89 | 2.87 | -5.75 | 19.3 | 3.96 |

| Monosaccharide C | 2.07 | 14.2 | 0.754 | 9.77 | -9.95 | 17.9 | -2.04 |

| Monosaccharide C* | 2.79 | 18.5 | 0.883 | 9.06 | -0.355 | 19.1 | -1.44 |

| Monosaccharide D | 1.90 | 21.3 | 0.814 | 7.47 | -7.61 | 16.67 | -1.86 |

| Monosaccharide D* | 2.58 | 18.98 | 0.758 | 7.66 | -1.04 | 19.13 | -1.55 |

Figure 12: Stretch, Bend, Stretch-bend, Torsion, Charge/Dipole, Van Der Waals and Dipole/Dipole components of MM2 geometry optimisation.

It can be seen from figure 9 that the main cause for the differing energies of A & A* and subsequently B & B* are differences in charge/dipole forces. These arise from the differing orientations of the polar oxygen atoms on the acetyl group. There are minimal differences in all other components of the MM2 optimisation. In C* and D*, the energetically unfavourable 'trans lactones' were formed- much less stable than their less-strained counterparts C & D.

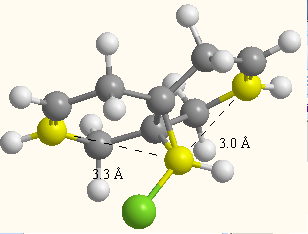

The reported diastereospeficity of the glycosidation of C to the β-anomer and D to the α-anomer may be explained by considering the relative energies of C vs. C* and D vs. D*. Both C* and D* were modelled as the higher energy confomers (by 13.1kcalmol-1 and 7.3kcalmol-1 respectively). Considering the relative abundancies of these confomers using the Boltzman distribution, it is clear that due to the large differences in energy between the confomers, C and D will exist in ~100% abundance relative to C* and D* (cf. Figure 10). One could also consider Curtin-Hammett Kinetics, which states "the product ratio will depend only on the difference in the free energy of the transition state going to each product, and not on the equilibrium constant between the intermediates."[8]. If we assume the higher energy trans lactone intermediates to also have a higher energy transition state, then we are able to further rationalise the high diastereospecificity of this reaction.

Figure 13: A table computing the relative abundancies (using the Boltzman Distribution) of C & D (i=o) versus C* & D* (i=1) where i= 0 is the lowest state using PM6 optimised energies.

In conclusion, PM6 modelling has successfully predicted the reactivity and relative stability of intermediates B & C (and their confomers) as well as their precursors, A & A' and B & B'.

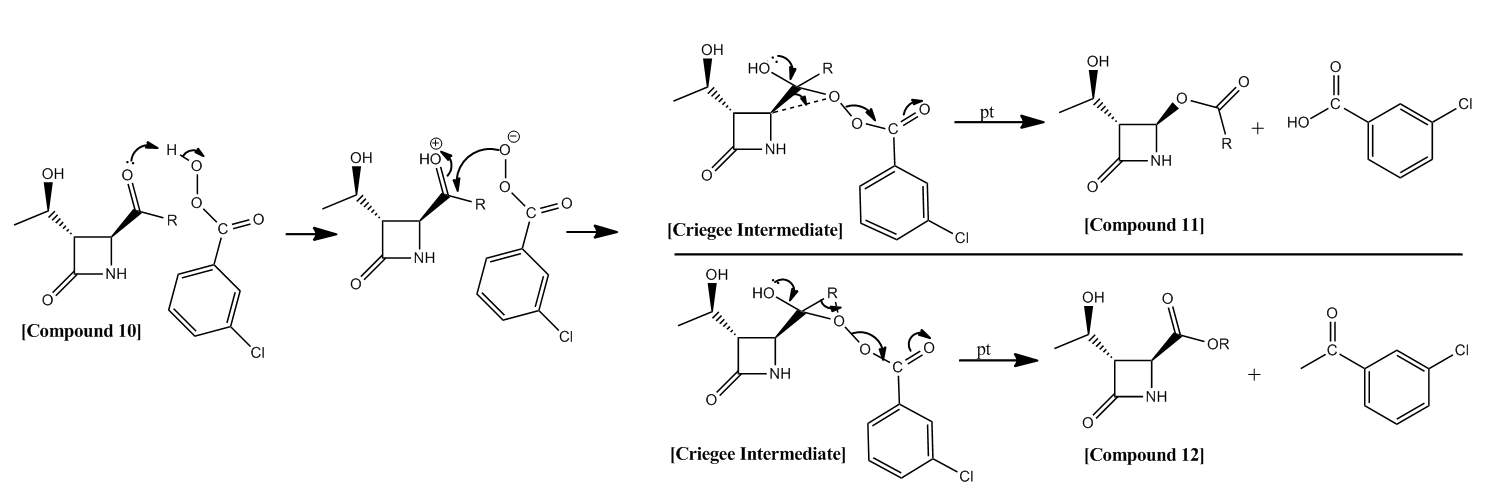

Investigating the regioselectivity of the Baeyer-Villiger reaction

The Baeyer-Villiger reaction involves the reaction of a ketone with a peracid to form an ester (alternatively formation of a lactone from a cyclic ketone) via an oxidative cleavage mechanism. Cleavage occurs between the carbonyl carbon and one of the 'previously ketonic' substituents. The reaction is driven by exothermicity of the (weak) O-O bond breaking. The reaction is regioselective with the substituent that can most effectively stabilise a partial positive charge migrating preferentially. Further to this, the reaction is stereospecific - the migrating substituent must be antiperiplanar to the O-O bond of the peracid leaving group. Moreover, the migrating substituent must also be antiperiplanar to an oxygen lone pair.

After protonation of the carbonyl, and subsequent nucleophillic attack by the peracid, the Baeyer Villiger reaction may proceed from the Criegee intermediate via two possible mechanisms, with the regioselectivity directly related to the nature of the migrating group (as mentioned above).

It is reported that the preferred migratory substituent is the one which is able to stabilise a positive charge most effectively. Considering the unsymetric nature of the Criegee intermediate, one would predict a certain degree of regioselectivity. It is reported in literature[9] that:

Where R=t-Bu, 100% regioselectivity is observed with oxygen insertion next to the R group.(Compound 12).

Where R=i-Pr, there is minimal regioselectivity, with approximately equimolar (52:48 (Compound 11:Compound 12)) contributions to the product from the regiomers.

Where R=c-Pr, 100% regioselectivity is observed with oxygen insertion next to the azetidinyl moiety (Compound 11).

Where R=Ph, there is again 100% regioselectivity, with oxygen insertion next to the azetidinyl moiety (Compound 11).

Figure 14: A reaction schemes showing two possible paths for the Baeyer-Villiger Reaction from its Criegee Intermediate.

Regioselectivity of Baeyer Villiger Reaction: R groups

The reaction involves an Oxygen lone pair (nO) with a σ* C-C bond in an antiperiplanar relationship, and a σ C-C bond and a σ* O-O bond in an antiperiplanar relationship. This results in a 1,2-alkyl shift (the RDS).

As the smallest possible 3o alkyl group, tBu is extremely effective at stabilising a partial positive charge. Therefore its 100% regioselectivity as the substituent which migrates to form compound 12 is not suprising.

iPr is a 2o alkyl, and therefore is not as effective at stabilising the partial positive charge. This justifies the reduced regioselectivity of the reaction when this R group is present. It could be inferred that the azetidinyl moiety is roughly as effective at positive charge stabilisation.

Where R = cPr, the 100% regioselectivity of this reaction can be attributed to a reduced hyperconjugative stabilisation of a partial positive charge due to the cyclic nature of the substituent (there are less C-H bonds). Moreover, the exocyclic C-C bond has increased sp2 character which may decrease the ability of the subtituent to migrate.

Where R=Ph, the 100% regioselectivity is suprising. One would infer that as an excellent stabiliser of positive charge, with R=Ph, the oxygen insertion would occur next to the Ph substituent. This is not the case. This may be due to steric effects - the Ph group is very bulky. Furthermore, as in R=cPr, the exocyclic C-C bond is likely to have a significant amount of sp2 character, inhibiting migration of this group.

NMR effective at distinguishing between Regiomers?

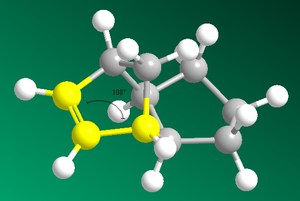

NMR shift were calculated with Gaussian/DFT optimisation and compared to experimental data to see if the regiomers were distinguishable using this method:

13C NMR shifts were calculated through MM2, MOPAC and subsequently Gaussian DFT optimisation. It is reported that the accuracy of this method is 3-5ppm.

NMR: 4-(isopropanoyloxy)-2-azetidinone (11) (R=iPr)

| Carbon Atom | δcalc(ppm) | δcorr(ppm) | δexp(ppm) | δcorr - exp(ppm) | Percentage Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon 4 | 170.50 | 175.87 | 177.6 | -1.73 | -0.974% |

| Carbon 6 | 155.14 | 161.13 | 167.2 | -6.07 | -3.63% |

| Carbon 5 | 75.31 | 75.31 | 75.9 | -0.59 | -0.777% |

| Carbon 8 | 63.53 | 63.53 | 65.2 | -1.67 | -2.56% |

| Carbon 9 | 60.42 | 60.42 | 63.9 | -3.48 | -5.44% |

| Carbon 2 | 32.59 | 32.59 | 34.0 | -1.41 | -4.15% |

| Carbon 7 | 20.34 | 20.34 | 21.3 | -0.96 | -4.51% |

| Carbon 1 | 17.99 | 17.99 | 18.9 | -0.91 | -4.81% |

| Carbon 3 | 15.48 | 15.48 | 18.8 | -3.32 | -17.7% |

Figure 15: A comparison of 13C NMR data for Compound 11 (R=iPr)

It can be seen that the majority of the calculated shifts are within the expected 3-5ppm deviation from literature. In all cases the calculated chemical shifts were lower than the experimental chemical shifts. This suggest a systematic error present in the DFT optimisation leading to a slight underestimate of chemical shift. The largest NMR shift deviation from literature is the C atom in the amide group. Although this shift was corrected using δcorr = 0.96δcalc + 12.2, a large deviation from literature was still present. This is likely due to limitations of the DFT model.

Aside from the C amide deviation, NMR shifts were within reported error. This suggests the conformation of compound 11 was calculated correctly. It must be noted that the NMR calculations assumed a static molecule, free of bond rotation. This explains the large percentage errors in Carbons 1 & 3 which one would assum to have the same environment on the NMR timescale.

NMR: 4-(isopropyloxycarbonyl)-2-azetidinone (12) (R=iPr)

| Carbon Atom | δcalc(ppm) | δcorr(ppm) | δexp(ppm) | δcorr - exp(ppm) | Percentage Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon 1 | 170.25 | 175.64 | 170.8 | 4.84 | 2.83% |

| Carbon 5 | 168.63 | 174.08 | 168.3 | 5.78 | 3.43% |

| Carbon 9 | 68.77 | 68.77 | 69.7 | -0.93 | -1.33% |

| Carbon 7 | 68.64 | 68.64 | 64.5 | 4.14 | 6.42% |

| Carbon 8 | 67.98 | 67.98 | 64.0 | 3.98 | 6.21% |

| Carbon 3 | 52.36 | 52.36 | 50.0 | 2.36 | 4.72% |

| Carbon 6 | 25.82 | 25.82 | 21.9 | 3.92 | 17.9% |

| Carbon 2 | 24.58 | 24.58 | 21.8 | 2.78 | 12.75% |

| Carbon 4 | 23.42 | 23.42 | 21.3 | 2.12 | 9.95% |

Figure 16: A comparison of 13C NMR data for Compound 12 (R=iPr)

Here, on the whole, calculated chemical shifts agreed within 3-5ppm of literature. Again, The largest NMR shift deviation from literature is the C atom in the amide group. In this NMR, most calculated shifts are an overestimate compared to literature, again suggesting a systematic error in the modelling.

A comparison of NMR shifts of compound 11 and compound 12 shows a notable difference in chemical shift between the regioisomers. NMR could therefore be a useful technique in determining the relative abundancies of regiomers in a solution. The inaccuracy of the shifts is attributable to limitations in the modelling, mainly due to the time-limitations of this modelling project. A modelling system with a greater number of paramaters is likely to produce shifts closer to literature.

Again, it must be noted that the NMR calculations assumed a static molecule, free of bond rotation. This explains the large percentage errors in Carbons 2 & 4 which one would assume to have the same environment on the NMR timescale. The relative errors of the NMR shift relative to experimental data are shown below in graphical form for both regiomers:

| Compound 11 | Compound 12 |

|---|---|

|

|

Figure 17:

An excellent way of confirming both regiochemistry and stereochemistry would be through calculation of 3JH-H coupling constants. The Karplus equation provides a primitive analysis, but calculation using quantum mechanical methods with Gaussian modelling is likely to produce more representative and accurate results. With the time constraint of the project however, 13C NMR was sufficient in confirming the regio- and stereochemistry of the Baeyer-Villiger reaction products with suprising accuracy.

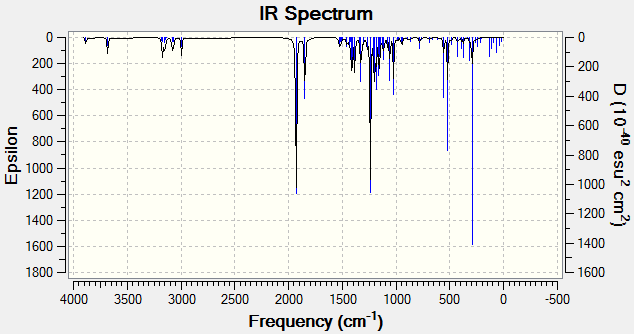

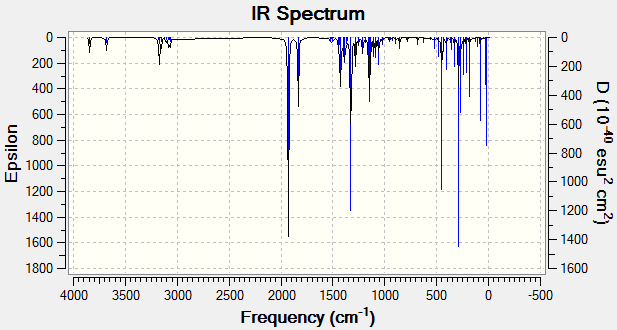

Infra-Red Analysis

Theoretically, Infra-Red Spectra are able to distinguish between the regioisomers as reported in literature. This is of course logical, as certain bonds (e.g. C=O) are in different environments in the regioisomers. In practise, conjugative effects can limit the effectiveness of IR absorption prediction/analysis using molecular modelling due to limitations of the model.

Theoretical IR spectra of the regiomers (R=i-Pr) (4-(isopropanoyloxy)-2-azetidinone (11) & 4-(isopropyloxycarbonyl)-2-azetidinone (12)) were produced using Gaussian DFT modelling.

| 4-(isopropanoyloxy)-2-azetidinone (11) | 4-(isopropyloxycarbonyl)-2-azetidinone (12) |

|---|---|

|

|

Figure 18: Calculated IR spectra of Regiomers 11 & 12 (R=iPr)

It is reported that IR frequencies are overestimated by approximately 8%. The calculated frequencies and adjusted frequencies are therefore shown in the table below:

Figure 19: IR absorption frequencies of Regiomers 11 & 12 (R=iPr)

Results show a relatively good agreement of frequency-corrected absorptions with literature and are usually within 50cm-1. This discrepancy is due to the inability of the model to fully quantify the conjugated nature of the bonds. Nonetheless, these results show a significant degree of agreement with literature, and on careful inspection, could be used to distinguish between regiomers. In a mixture of the regiomers however, 13C NMR is a much more rewarding technique.

Conclusion

Molecular mechanics (MM2, MMFF94), semi-empirical molecular orbital (MOPAC PM6/AM1/RM1) theory and (Gaussian) DFT-based molecular orbital methods were demonstrated to be useful in solving the chemical problems above, although most problems were solvable by chemical knowledge and intuition. Nonetheless, mechanics are a useful compliment and are able to confirm complex assumptions, despite, at times, the primitive nature of the functions.

In places, such as for the hydrogenation of the cyclopentadiene dimer, the discussed computational methods were highly useful tools in determining the thermodynamic product. In others, (e.g. the dimerisation reaction itself, and predicting geometries in monosaccharide chemistry), the limitations of MM2 & MMFF94 became apparent. Semi-empirical methods such as PM6 were much more useful in this case, and provided significantly more accurate results. Again however, these predictions are likely to differ significantly from the solvent-effected reaction in real-life. It must be noted that without the semi-empirical techniques, some experimentally observed effects may have been hard to rationalise (e.g. geometries of the open rings in A & B).

In the mini-project, the regioisomers could've easily been distinguished with an experimentally obtained 1H NMR spectrum (as stated in literature) rather than a modelled 13C spectrum and loosely agreeing IR spectra, which were significantly time-consuming to calculate. The advantage of analysis without the 'wet lab' however (although often primitive), is a highly useful technique for predicting the chemistry of many reactions. Advances from the original MM1 technique are staggering, and it must be noted that the models used in this project were only of a medium complexity (for convenience sake).

Whilst the accuracy of the computed 13C NMR shifts by GIAO was suprisingly accurate in places, the method is severely limited in its treatment of molecules as remaining static. For example, the equivalence of atoms achieved through high speed bond rotation is well reported and therefore the usefulness of a modelling technique with a static approach is limited. Shifts for C atoms near polar functional groups (e.g. OH) were poorly estimated. This may be a result of poorly modelled solvent-effects of the GIAO method.

References

- ↑ W. C. Herndon, C. R. Grayson, J. M. Manion, J. Org. Chem., 1967, 32, 529 DOI:10.1021/jo01278a003

- ↑ Rezpa, Third Year Computational Labs, Module 1

- ↑ S. W. Elmore and L. Paquette, Tetrahedron Letters, 1991, 319;DOI:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0

- ↑ W. F. Maier, P. V. R. Schleyer, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1981, 103, 1900 DOI:10.1021/ja00398a003

- ↑ B. Halton, R. Boese, H. S. Rzepa, J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2, 1992, 447

- ↑ B. Halton, S. G. G. Russell, J. Org. Chem., 1991, 56, 5556 DOI:10.1021/jo00019a015

- ↑ https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=File:Anomer2.jpg

- ↑ Carey, Francis A.; Sundberg, Richard J.; (1984). Advanced Organic Chemistry Part A Structure and Mechanisms (2nd ed.). New York N.Y.: Plenum Press. ISBN 0-306-41198-9

- ↑ M. Laurent, M. Cérésiat, J. Marchand-Brynaert, J. Org. Chem., 2004, 69, 3197 DOI:10.1021/jo030377y

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-9550 - NMR Compound 11

http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-9551 - NMR Compound 12