Rep:Mod:LMB123

Lily Beadle Organic Synthesis Modelling

This computational experiment uses molecular mechanics to model compounds, predict several different properties such as regioselectivity or enantioselectivity and to generate NMR spectra. The study is split into 2 parts. The first part deals with the regioselectivity of the dimerisation of cyclopentadiene and of its product's subsequent hydrogenation. An example of atropisomerism is investigated for a ketone intermediate in the synthesis of Taxol and 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra calculations are carried out for a different Taxol intermediate. The second part looks into the enantioselectivty of the Shi and Jacobsen epoxidations of the two alkenes styrene and β-methylstyrene as well as investigating different features such as NMR spectra and optical rotation.

Part 1

Aims

- To use molecular mechanics to predict the geometry and regioselectivity of:

- The hydrogenation of cyclopentadiene dimer

- The conformation/atropisomerism of a large ring ketone intermediate in one synthesis of the anti-cancer drug Taxol*

- To predict the 13C and 1H NMR spectra of a related Taxol intermediate and to compare the predictions with the measured values reported in the literature.

- To gain familiarity with the use of an digital data repository ("assigning a doi to data")

- To perform searches of the literature for each topic in order to cite in your final report any relevant references to each experiment as appropriate

- To present the results in the form of a Wiki page

Cyclodimerisation of cyclopentadiene and hydrogenation of the endo dimer

By inspecting the relative stabilities of the following compounds it is deduced which of each pair is the less strained and/or hindered in a thermodynamic context. If a reaction is under kinetic control this would imply that the transition state(s) is/are stable whereas under thermodynamic control the product stability wins out.

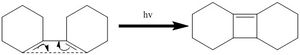

Cyclodimerisation of cyclopentadiene

The following reaction is inspected to determine using an molecular mechanics technique whether the cyclodimerisation of cyclopentadiene and hydrogenation of the dimer are kinetically or thermodynamically controlled. The geometries of the dimers 1-4 were optimised using the MMFF94s Force Field option with the Conjugate gradients algorithm in Avogadro.

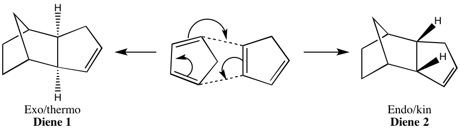

Dicyclopentadiene can have an exo or endo form showed in the following scheme.

Cyclopentadiene dimer 1 Cyclopentadiene dimer 2

By modelling dimer 1 vs dimer 2 the relative stabilities of each can be calculated and can indicate which of pair is less strained/hindered in a thermodynamic context. The computational analysis produces the following results:

| Dimer | Total bond stretching energy | Total angle bending energy | Total torsional energy | Total van der Waals energy | Total electrostatic energy | Total energy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimer 1 | 3.54 | 30.77 | -2.73 | 12.80 | 13.01 | 55.37 |

| Dimer 2 | 3.46 | 33.20 | -2.95 | 12.35 | 14.18 | 58.19 |

According to these results the exo product, dimer 1, has the lowest total energy and thus is the thermodynamic product. In the results the angle bending energy is the energy that contributes most to the total energy difference between the two isomers and this is significantly higher in product 2. However as discussed the endo product, dimer 2, is the major product of the reaction. This would imply that the reaction is under kinetic control as the less thermodynamically stable product is formed. By visual observation of the overlap of the reactants HOMO and LUMO a qualitative prediction of the kinetic product could be made based on qualitative frontier molecular theory. The transition state to form dimer 2 is more accessible and there are favourable interactions between the frontier orbitals of the diene and the dienophile at the back of the molecule which are not present in the formation of the eco product.[1]

Diagram taken from Clayden.[2]

From experimental data [1] the endo product, dimer 2, is preferred and the the dimerisation of cyclopentadiene is kinetically controlled.

Hydrogenation of cyclopentadiene dimer

Hydrogenation of the endo dimer 2 proceeds to the intermediate of either dihydro 3 or 4. Only after prolonged hydrogenation is the tetrahedron derivative formed.

3 and 4 are compared thermodynamically in the table below.

| Dimer | Total bond stretching energy | Total angle bending energy | Total torsional energy | Total van der Waals energy | Total electrostatic energy | Total energy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimer 3 | 3.31 | 31.94 | -1.47 | 13.64 | 5.12 | 50.45 |

| Dimer 4 | 2.82 | 24.69 | -0.38 | 10.64 | 5.15 | 41.26 |

From these results we can see that intermediate 4 is more thermodynamically stable than 3. If the hydrogenation of dimer 2 is a thermodynamic process then the product will be formed via 4. The stretching, bending, torsional and Van der Waals contributions to the energy are all smaller for the thermodynamic product 4. The exception is that the electrostatic energy is lower for dimer 3 as the unfavourable steric repulsions between the olefinic hydrogen atoms and the ones bridging the two rings are minimised.

It has been reported that product 4 is formed thus this reaction is under thermodynamic control.[3]

Atropisomerism in an Intermediate relating to the synthesis of Taxol

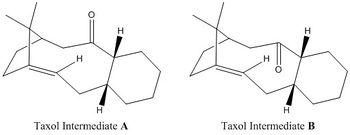

A key intermediate in the total synthesis of the cancer drug Taxol [4] is initially synthesised with the carbonyl group pointing up or down as shown in the following diagrams.

On standing the compound isomerises to the more thermodynamically stable product suggesting there is a low barrier between the two. On subsequent functionalisation of the alkene this intermediate reacts surprisingly slowly. The two intermediates are thermodynamically inspected and compared.

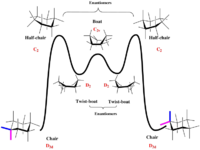

The conformations of the hexane ring has a significant effect on the minimised energy of the two different conforms. In cyclohexane the following energy graph demonstrates how energy can vary with ring flipping.

In the two taxol intermediates there are different chair conformations possible for each intermediate. Two chair conformations of intermediate B are shown below to demonstrate this.

| Intermediate | Total bond stretching energy | Total angle bending energy | Total torsional energy | Total van der Waals energy | Total electrostatic energy | Total energy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (chair ring 1) | 7.61 | 18.83 | 0.30 | 33.18 | -0.05 | 60.57 |

| B (chair ring 2) | 8.54 | 21.62 | 7.49 | 35.85 | 0.38 | 75.19 |

B (chair ring 1) has the optimised structure Optimised structure of Intermediate B

B (chair ring 1) has the structure Alternative ring conformation of B

Both conforms have the ring in a chair conformation but the rest of the molecule is arranged differently in relation to the ring.

For both A and B the lowest conform of both has been found and compared having considered whether the ring is of a chair, boat, twist boat etc. conformation. Those chosen are shown in the table below, both with the ring in chair conformations. All boat conformations produce unfavourable steric repulsions from the flagpole hydrogens.[6]

Optimised structure of Intermediate A

Optimised structure of Intermediate B

| Intermediate | Total bond stretching energy | Total angle bending energy | Total torsional energy | Total van der Waals energy | Total electrostatic energy | Total energy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 7.70 | 28.19 | 0.28 | 33.18 | 0.31 | 70.54 |

| B | 7.61 | 18.83 | 0.30 | 33.18 | -0.05 | 60.57 |

| A alkane parent | 6.95 | 31.99 | 9.52 | 32.74 | 0.00 | 81.75 |

| B alkane parent | 6.61 | 23.94 | 10.10 | 32.08 | 0.00 | 73.18 |

B is the thermodynamically favoured product. The angle bending energy has the greatest influences on the above results and is the contribution that varies the most significantly. The "Olefin Strain" (OS) energy (the difference in strain energy between the alkene and its parent hydrocarbon)[7], was calculated for both atropisomers to determine the relative reactivities of the alkenes.

Compound A: 81.75 - 70.54 = 11.21 kcal mol-1 Compound B: 73.18 - 60.63 = 12.61 kcal mol-1 Both these values are exceptionally low and reveal that these two intermediates are "hyperstable" olefins [7]. They actually have a lower total energy than their corresponding parent hydrocarbon and thus are very slow to react. Since B has the higher OS value it is expected to react more quickly than atopisomer A.

The molecules shown below C and D are derivates of A and B respectively for which spectroscopic information has been reported. The1H and the 13C spectra are simulated and compared with literature. The structures were optimised using the MMFF94s force field and the Conjugate Gradients algorithm in Avogadro.

| Intermediate | Total bond stretching energy | Total angle bending energy | Total torsional energy | Total van der Waals energy | Total electrostatic energy | Total energy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C (428.032 kJ/mol) | 14.39 | 28.27 | 13.84 | 50.55 | -6.32 | 102.23 |

| D (502.988 kJ/mol) | 15.79 | 38.01 | 17.29 | 53.80 | -7.62 | 120.14 |

As expected from the results above for intermediates A & B, out of this pair intermediate C is the most thermodynamically stable as it has the lowest total strain energy.

The predicted spectra is compared with literature values below.

Intermediate C NMR[8]

|

|

| Media:Taxol_Int_C_1H_NMR_Summ.txt | Media:Taxol_Int_C_13C_NMR_Summ.txt |

Intermediate D NMR[9]

|

|

| Media:Taxol_Int_D_1H_NMR_Summ.txt | Media:Taxol_Int_D_13C_NMR_Summ.txt |

Analysis of NMR of Taxol Intermediate C

| H Atom | Generated δ (ppm) | Literature δ (ppm) | Δδ (ppm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ha | 5.53 | 4.48 | 0.69 |

| Hb | 2.68 | 2.99 | -0.31 |

| Hc | 2.35 | 1.00-0.80 | 1.35-1.55 |

Only three key hydrogens that are identified in the literature are shown above in the table. For more spectral information see the NMR summary. The significant hydrogen above is Hc as it is easily identifiable as a bridging hydrogen and there is significant deviation between the computational value and the reported value in literature.[10] The deviations for Ha and Hb are minor.

| C Atom | Generated δ (ppm) | Literature δ (ppm) | Δδ (ppm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 33.18 | 32.66 | 0.52 |

| 2 | 60.33 | 52.52 | 7.81 |

| 3 | 64.55 | 56.19 | 8.36 |

| 4 | 91.27 | 72.88 | 18.39 |

| 5 | 40.07 | 35.85 | 4.22 |

| 6 | 22.05 | 20.96 | 1.09 |

| 9 | 44.19 | 38.81 | 5.38 |

| 10 | 47.63 | 45.76 | 1.87 |

| 11 | 32.87 | 28.79 | 4.08 |

| 12 | 116.91 | 125.33 | -8.42 |

| 13 | 149.37 | 144.63 | 4.74 |

| 14 | 27.36 | 25.66 | 1.70 |

| 15 | 31.46 | 28.29 | 3.17 |

| 16 | 52.85 | 46.80 | 6.05 |

| 17 | 46.64 | 39.80 | 6.84 |

| 18 | 214.46 | 218.79 | -4.33 |

| 19 | 54.01 | 48.50 | 5.51 |

| 20 | 26.87 | 23.86 | 3.01 |

| 21 | 21.56 | 18.71 | 2.85 |

| 24 | 30.68 | 26.88 | 3.80 |

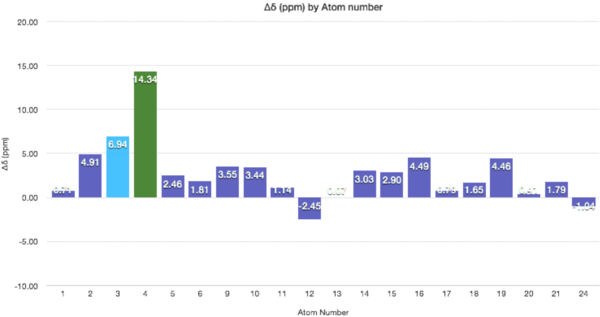

The graph above demonstrates clearly the varying deviations from the NMR. The most significant deviation is at C4 which is attached to the 2 sulphurs. The electropositive nature of sulphur is underestimated (adjacent electropositive atoms bring the NMR upfield) and/or the strain of a tetrahedral carbon is overestimated here (brings the NMR downfield). The differences in chemical shifts for the carbon atoms 2, 3, 4, 9, 12, 16, 17, and 19 are higher than 5 ppm which suggests an inaccurate conformation of the molecule in these regions (assuming literature values are correct). |Δδ|= 5.11 ppm, Max Δδ = 18.39 ppm

Analysis of NMR of Taxol Intermediate D

| H Atom | Generated δ (ppm) | Literature δ (ppm) | Δδ (ppm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ha | 5.58 | 5.21 | 0.17 |

| Hb | 2.11 | 1.58 | 0.53 |

The deviations are small and the generated results match those in the literature well.[10]

| C Atom | Generated δ (ppm) | Literature δ (ppm) | Δδ (ppm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 36.18 | 35.47 | 0.71 |

| 2 | 56.21 | 51.30 | 4.91 |

| 3 | 67.47 | 60.53 | 6.94 |

| 4 | 88.95 | 74.61 | 14.34 |

| 5 | 41.19 | 38.73 | 2.46 |

| 6 | 21.64 | 19.83 | 1.81 |

| 9 | 44.37 | 40.82 | 3.55 |

| 10 | 46.72 | 43.28 | 3.44 |

| 11 | 31.98 | 30.98 | 1.14 |

| 12 | 118.45 | 120.90 | -2.45 |

| 13 | 148.79 | 148.72 | 0.07 |

| 14 | 28.59 | 25.56 | 3.03 |

| 15 | 25.11 | 22.21 | 2.90 |

| 16 | 55.43 | 50.94 | 4.49 |

| 17 | 37.57 | 36.78 | 0.79 |

| 18 | 213.14 | 211.49 | 1.65 |

| 19 | 49.99 | 45.53 | 4.46 |

| 20 | 25.76 | 25.35 | 0.41 |

| 21 | 23.18 | 21.39 | 1.79 |

| 24 | 28.96 | 30.00 | -1.04 |

The deviations for intermediate D are less marked than for intermediate C. The both the average |Δδ|, equal to 3.12 ppm, and the the maximum deviation, equal to 14.34 ppm, are less than the comparative values for C. Again carbon 4 has the highest deviation for possible reasons explained above. This indicate the conformation is wrong in this region.

A Look at Thermodynamic Properties

| Energy consideration | Intermediate C | Intermediate D |

|---|---|---|

| Zero-point correction (Hartree/Particle) | 0.467225 | 0.467687 |

| Thermal correction to Energy | 0.489129 | 0.489218 |

| Thermal correction to Enthalpy | 0.490073 | 0.490162 |

| Thermal correction to Gibbs Free Energy | 0.418837 | 0.420438 |

| Sum of electronic and Zero-Point Energies | -1651.389632 | -1651.415539 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal Energies | -1651.367728 | -1651.394008 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies | -1651.366784 | -1651.393064 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies | -1651.438020 | -1651.462789 |

These results are in line with those above and demonstrate that intermediate A has lower energies and is thus more thermodynamically stable.

Part 2

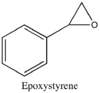

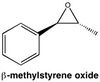

styrene and beta-methyl styrene

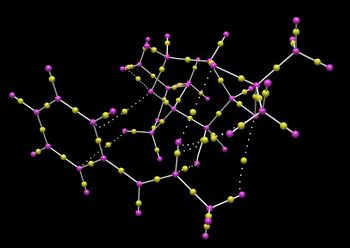

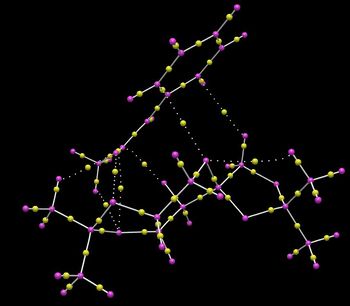

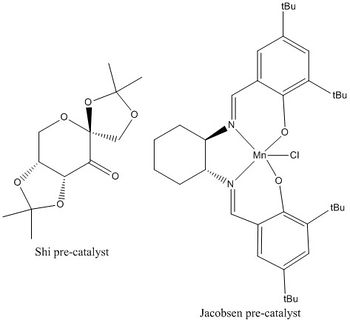

The crystal structures of the Shi and Jacobsen catalysts

The Shi and Jacobsen catalysts were found on the Cambridge crystal database (CCDC) using the programme Conquest and their structure was analysed using he programme Mercury. The results are reported below.

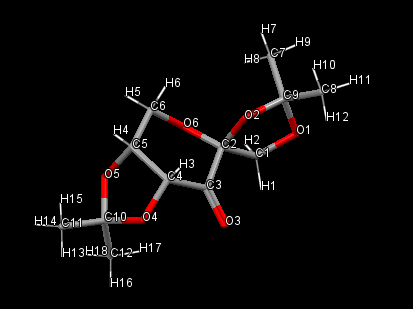

The Shi catalyst

| C-O | Bond length (Å) |

|---|---|

| C1-O1 | 1.429 |

| C9-O1 | 1.423 |

| C2-O2 | 1.423 |

| C2-O6 | 1.408 |

| C9-O2 | 1.454 |

| C4-O4 | 1.415 |

| C10-O4 | 1.456 |

| C5-O5 | 1.437 |

| C10-O5 | 1.428 |

The order of C-O bond lengths in the pyranose ring is as follows: C4-O4<C2-O2<C5-O5. The smallest value obtained for C4-O4 suggests a higher amount of strain.

C9-O1 and C10-O5 are of a comparative length whilst C9-O2 is similar to C10-O4.

At the anomeric centre the C-O bond length of 1.408Å is smaller than the literature value of a simple pyranose unit, 1.426Å. [11]

Between molecules short distance interactions are further observed. By definition these are lower than the sum of their Van der Waals radii) These are essentially hydrogen bonds but dipole-dipole interactions are also observed.

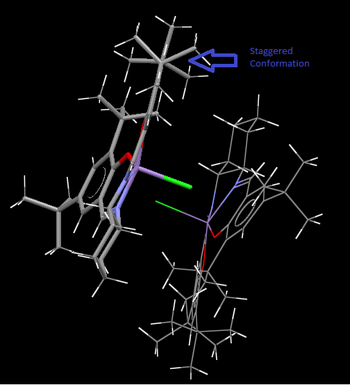

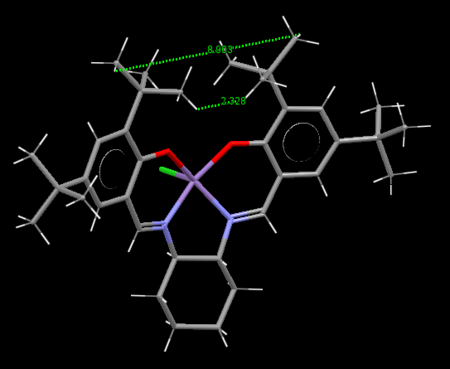

The Jacobsen catalyst

The tButyl groups form a staggered conformation in relation to the other on the same ring as this is the most stable conformation.

Attracted Van der Waals forces form between hydrogens on the tButyl groups. These will form between the closer hydrogens.

It is expected that hydrogen bonds will form between the nitrogen atoms and hydrogen atoms on adjacent molecules as well as dipole-dipole interactions between C & H atoms.

Calculated NMR properties of the epoxide products

The first step in generating the NMRs of epoxystyrene and trans-β-methylepoxystyrene was to optimise their geometry using Avogadro (force field: MMFF94s, algorithm: Conjugate gradients). These values were then compared with values from literature.[12][13]

Epoxystyrene

Media:Epoxystyrene_1H_NMR_summ.txt

Media:Epoxystyrene_13C_NMR_summ.txt

| Energy Measurement | Total bond stretching energy | Total angle bending energy | Total torsional energy | Total van der Waals energy | Total electrostatic energy | Total energy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy kcal mol-1 | 1.84 | 1.42 | 2.35 | 13.67 | 3.08 | 21.62 |

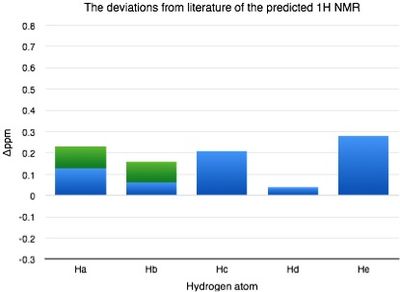

| Hydrogen atom | δ (ppm) | Literature value (ppm) | Δδ (ppm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| H(a) | 7.49 | 7.26-7.36 | 0.13-0.23 |

| H(b) | 7.30 | 7.26-7.36 | 0.06-0.16 |

| H(c) | 3.66 | 3.87 | 0.21 |

| H(d) | 3.11 | 3.15 | 0.04 |

| H(e) | 2.53 | 2.81 | 0.28 |

From the graph above the deviations calculated are very small suggesting a good match between predicted and literature results. This indicates a correct configuration of molecule and assignment of NMR. |Δδ| = 0.14-0.18ppm, max Δδ = 0.28ppm

| Carbon atom | δ (ppm) | Literature value (ppm) | Δδ (ppm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | 124.13 | 128.4 | -4.27 |

| C2 | 122.95 | 125.5 | -2.55 |

| C3 | 123.41 | 128.4 | -4.99 |

| C4 | 122.95 | 125.5 | -2.55 |

| C5 | 135.14 | 137.6 | -2.46 |

| C6 | 118.27 | 125.5 | -7.23 |

| C7 | 54.05 | 52.4 | 1.64 |

| C8 | 53.45 | 51.2 | 2.25 |

The most significant deviations are found in the aromatic ring, in particular C6 which is ortho to the subsituent group. |Δδ| = 3.49ppm, max Δδ = -7.23ppm

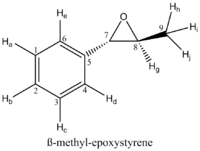

trans-β-methylepoxystyrene

| Energy Measurement | Total bond stretching energy | Total angle bending energy | Total torsional energy | Total van der Waals energy | Total electrostatic energy | Total energy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy kcal mol-1 | 1.89 | 1.74 | 2.90 | 14.33 | 3.03 | 23.12 |

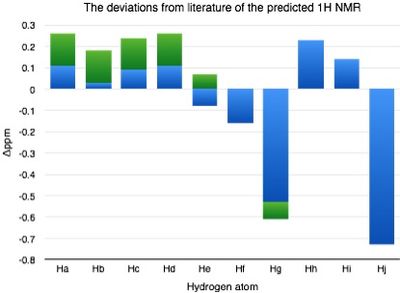

| Hydrogen atom | δ (ppm) | Literature value (ppm) | Δδ (ppm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| H(a) | 7.50 | 7.24-7.39 | 0.11-0.26 |

| H(b) | 7.42 | 7.24-7.39 | 0.03-0.18 |

| H(c) | 7.48 | 7.24-7.39 | 0.09-0.24 |

| H(d) | 7.50 | 7.24-7.39 | 0.11-0.26 |

| H(e) | 7.31 | 7.24-7.39 | -0.08-0.07 |

| H(f) | 3.41 | 3.57 | -0.16 |

| H(g) | 2.79 | 3.32-3.40 | -0.61--0.53 |

| H(h) | 1.68 | 1.45 | 0.23 |

| H(i) | 1.59 | 1.45 | 0.14 |

| H(j) | 0.72 | 1.45 | -0.73 |

The deviations are more significant for trans-β-methylepoxystyrene than for epoxystyrene however they are still relatively very low. Hj stands out as the most inaccurate result. The literature has all of Hh, Hi and Hj equal to the same value where as computationally they have been locked in a certain conform. This is a flaw in the computational method. Hg here is comparable to He in epoxystyrene. In both cases this hydrogen shows deviation from the literature suggesting that the configuration is wrong. |Δδ| = 0.22-0.29ppm , max Δδ = -0.73ppm.

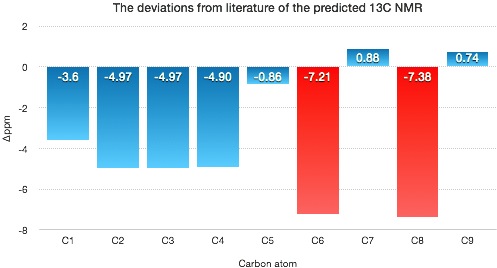

| Carbon atom | δ (ppm) | Literature value (ppm) | Δδ (ppm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | 124.07 | 128.3 | -3.6 |

| C2 | 122.73 | 127.7 | -4.97 |

| C3 | 123.33 | 128.3 | -4.97 |

| C4 | 122.80 | 127.7 | -4.90 |

| C5 | 134.98 | 135.84 | -0.86 |

| C6 | 118.49 | 125.7 | -7.21 |

| C7 | 60.58 | 59.7 | 0.88 |

| C8 | 52.32 | 59.7 | -7.38 |

| C9 | 18.84 | 18.1 | 0.74 |

The most significant deviations are found in the aromatic ring, in particular C6 which is ortho to the subsituent group. C8 also shows sting deviation suggests the conformation in this region is wrong. |Δδ| = 3.21ppm, max Δδ = -7.38ppm.

Determination of the absolute configuration of the epoxide products

Calculated chiroptical properties

The NMR on it's own is not enough to determine the configurations of each of the products. For each case the chiral properties were investigated and compared to literature.

| Parameter | Epoxystyrene | β-methyl epoxystyrene |

|---|---|---|

| Literature value for Optical Rotation (in chloroform) | -33.3° (589 nm) (R) [14] | -43.6° (589 nm) (S,S) [15] |

| Calculated Optical Rotation (in chloroform) | 30.6° (589 nm), °94.19 (365 nm) | -46.7° (589 nm), °-137.68 (365 nm) |

The values obtained for the optical rotation of both products are of the same range than the ones found in literature, however with an opposite sign in the case of styrene oxide. Hence the computed enantiomers have the following absolute configurations: (R)-(+)-styrene oxide and (R,R)-(-)-methylstyrene oxide.

Calculated Transition States for the Epoxidation

The relative computed free energy of the transition state can be used as a check for the enantiomeric assignment obtained by comparing computed and calculated optical rotations of the epoxides. Using this data it was then possible to find the ratio of concentrations between the two enantiomers for each epoxidation. The enantiomeric excess (ee) of one enantiomer over the other is calculated by using the following formulaCite error: Invalid parameter in <ref> tag:

Using Shi catalyst

Styrene

The thermodynamic quantities of the eight possible transition states for the epoxidation of β-methylstyrene using the Shi catalyst are summarised in the table below.

| Energy/Transition State | Trans 1 (R) | Trans 1 (S) | Trans 2 (R) | Trans 2 (S) | Trans 3 (R) | Trans 3 (S) | Trans 4 (R) | Trans 4 (S) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zero-point correction (Hartree/particle) | 0.439915 | 0.439602 | 0.439626 | 0.439301 | 0.439753 | 0.439940 | 0.439537 | 0.439598 |

| Thermal correction to Energy | 0.463584 | 0.464563 | 0.464361 | 0.464184 | 0.464452 | 0.464504 | 0.464247 | 0.464404 |

| Thermal correction to Enthalpy | 0.465528 | 0.465507 | 0.465306 | 0.465128 | 0.465396 | 0.465448 | 0.465161 | 0.465348 |

| Thermal correction to Gibbs Free Energy | 0.386893 | 0.384919 | 0.385610 | 0.386009 | 0.386060 | 0.387457 | 0.386349 | 0.384790 |

| Sum of electronic and zero-point Energies | -1303.677681 | -1303.679145 | -1303.676222 | -1303.670886 | -1303.683121 | -1303.675190 | -1303.684857 | -1303.683695 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal Energies | -1303.653012 | -1303.654184 | -1303.651487 | -1303.646003 | -1303.658421 | -1303.650626 | -1303.660147 | -1303.658890 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies | -1303.652068 | -1303.653240 | -1303.650542 | -1303.645059 | -1303.657477 | -1303.649682 | -1303.659202 | -1303.657945 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies | -1303.730703 | -1303.733828 | -1303.730238 | -1303.724178 | -1303.736813 | -1303.727673 | -1303.738044 | -1303.738503 |

| Parameter/Transiton State | TS1 | TS2 | TS3 | TS4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Free energy difference ΔG[(R)-(S)] (kcal/mol) | 3.125*10-3 | 6.060*10-3 | 9.14*10-3 | 4.59*10-4 |

| Free energy difference ΔG[(R)-(S)] (J/mol) | 13.075 | -25.35504 | -32.24276 | 1.920456 |

| Ratio of concentrations K; K=exp[-ΔG/(RT)] | 0.9947 | 0.9898 | 0.9871 | 0.9992 |

| ee (%) | 98.94 (R) | 97.96 (S) | 97.42 (S) | 99.84 (R) |

Although the transition states energy values are lower for the (S) configuration the table above suggests that it is the (R) configuration that is formed through transition state 4 with an ee equal to 99.84%. This matches with the results from the optical rotation values.

trans-β-methyl styrene

The thermodynamic quantities of the eight possible transition states for the epoxidation of β-methylstyrene using the Shi catalyst are summarised in the tablebelow.

| Energy/Transition State | (R,R) Trans 1 | (S,S) Trans 1 | (R,R) Trans 2 | (S,S) Trans 2 | (R,R) Trans 3 | (S,S) Trans 3 | (R,R) Trans 4 | (S,S) Trans 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zero-point correction (Hartree/particle) | 0.468068 | 0.468080 | 0.467219 | 0.467596 | 0.468048 | 0.467091 | 0.467695 | 0.467219 |

| Thermal correction to Energy | 0.494251 | 0.494312 | 0.493778 | 0.493965 | 0.494175 | 0.493469 | 0.493949 | 0.493719 |

| Thermal correction to Enthalpy | 0.495195 | 0.495256 | 0.494722 | 0.494909 | 0.495119 | 0.494413 | 0.494893 | 0.494663 |

| Thermal correction to Gibbs Free Energy | 0.413390 | 0.412657 | 0.410181 | 0.413022 | 0.413481 | 0.411621 | 0.413280 | 0.411294 |

| Sum of electronic and zero-point Energies | -1342.968292 | -1342.962520 | -1342.962195 | -1342.961029 | -1342.974705 | -1342.968296 | -1342.978027 | -1342.968817 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal Energies | -1342.942109 | -1342.936287 | -1342.935636 | -1342.934660 | -1342.948578 | -1342.941918 | -1342.951773 | -1342.942317 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies | -1342.941165 | -1342.935343 | -1342.934692 | -1342.933715 | -1342.947634 | -1342.940974 | -1342.950829 | -1342.941373 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies | -1343.022970 | -1343.017942 | -1343.019233 | -1343.015603 | -1343.029272 | -1343.023766 | -1343.032443 | -1343.024742 |

| Parameter/Transiton State | TS1 | TS2 | TS3 | TS4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Free energy difference ΔG[(S,S)-(R,R)] (kcal/mol) | 5.028*10-3 | 3.630*10-3 | 5.506*10-3 | 7.701*10-3 |

| Free energy difference ΔG[(S,S)-(R,R)] (J/mol) | 21.037152 | 15.18792 | 23.037104 | 32.220984 |

| Ratio of concentrations K; K=exp[-ΔG/(RT)] | 0.9915 | 0.9939 | 0.9907 | 0.9871 |

| ee of (S,S) (%) | 98.30 | 98.78 | 98.14 | 96.28 |

The transition state with the lowest energy and the most stable forms the (R,R) epoxide which is the predicted major product. However the above results match with literature in saying that it is the (S,S) epoxide that is formed.[15].

Using Jacobsen catalyst

Styrene

| Energy/Transition State | (S) Trans 1 | (R) Trans 1 | (S) Trans 2 | (R) Trans 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zero-point correction (Hartree/particle) | 0.735593 | 0.735629 | 0.736520 | 0.736155 |

| Thermal correction to Energy | 0.776531 | 0.776522 | 0.777159 | 0.776698 |

| Thermal correction to Enthalpy | 0.777476 | 0.777466 | 0.778103 | 0.777642 |

| Thermal correction to Gibbs Free Energy | 0.663174 | 0.663829 | 0.664459 | 0.664222 |

| Sum of electronic and zero-point Energies | -3343.896778 | -3343.889089 | -3343.891130 | -3343.890229 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal Energies | -3343.855840 | -3343.848196 | -3343.850491 | -3343.849686 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies | -3343.854896 | -3343.847252 | -3343.849547 | -3343.848742 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies | -3343.969197 | -3343.960889 | -3343.963191 | -3343.962162 |

| Parameter/Transiton State | TS1 | TS2 |

|---|---|---|

| Free energy difference ΔG[(R)-(S)] (kcal/mol) | 8.308*10-3 | 1.029*10-3 |

| Free energy difference ΔG[(R)-(S)] (J/mol) | 34.760672 | 4.305336 |

| Ratio of concentrations K; K=exp[-ΔG/(RT)] | 0.9861 | 0.9983 |

| ee of (R) (%) | 97.22 | 99.66 |

These results would indicate that the (R) configuration is formed.

trans-β-methyl styrene

| Energy/Transition State | (R,R) Trans 1 | (S,S) Trans 1 | (R,R) Trans 2 | (S,S) Trans 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zero-point correction (Hartree/particle) | 0.763619 | 0.763696 | 0.764409 | 0.764820 |

| Thermal correction to Energy | 0.806154 | 0.806239 | 0.806641 | 0.806700 |

| Thermal correction to Enthalpy | 0.807098 | 0.807183 | 0.807585 | 0.807644 |

| Thermal correction to Gibbs Free Energy | 0.689616 | 0.689476 | 0.690947 | 0.693544 |

| Sum of electronic and zero-point Energies | -3383.188478 | -3383.179597 | -3383.184384 | -3383.183068 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal Energies | -3383.145943 | -3383.137053 | -3383.142153 | -3383.141188 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies | -3383.144999 | -3383.136109 | -3383.141209 | -3383.140244 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies | -3383.262481 | -3383.253816 | -3383.257847 | -3383.254344 |

| Parameter/Transiton State | TS1 | TS2 |

|---|---|---|

| Free energy difference ΔG[(S,S)-(R,R)] (kcal/mol) | 8.665*10-3 | 3.503*10-3 |

| Free energy difference ΔG[(S,S)-(R,R)] (J/mol) | 36.254360 | 14.656552 |

| Ratio of concentrations K; K=exp[-ΔG/(RT)] | 0.9855 | 0.9941 |

| ee of (S,S) (%) | 97.10 | 98.82 |

Using the Jacobsen catalyst, according to the results above the product formed is of (S,S) configuration.

Investigating the non-covalent interactions in the active-site of the reaction transition state

Orbital |

Investigating the Electronic topology (QTAIM) in the active-site of the reaction transition state

Suggesting new candidates for investigations

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 D.R.J.Palmer, "Integration of Computational and Preparative Techniques To Demonstrate Physical Organic Concepts in Synthetic Organic Chemistry: An Example Using Diels-Alder Reactions", J. Chem. Ed., 2004, 81, 1633-36. DOI:10.1021/ed081p1633

- ↑ Clayden, Greeves, Warren and Wothers, "Organic Chemistry", Oxford University Press, 2nd ed., 2007, 35, 912-917.

- ↑ D.Skala and J. Hanika, "Petroleum and coal", 2003, 45, 3-4.

- ↑ S. W. Elmore and L. Paquette, "The First Thermally-Induced Retro-oxy-Cope Rearrangment", Tetrahedron Letters, 1991, 3, 319-322. DOI:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0

- ↑ Henry Rzepa, "Conformational analysis", Department of Chemistry, Imperial College London, 2004, Cycloalkanes.

- ↑ Clayden, Greeves, Warren and Wothers, "Organic Chemistry", Oxford University Press, 2nd ed., 2007, 35, 457-467.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 W. F. Mayer, P. von Rague Schleyer, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1981, 103, 1891.

- ↑ Int C NMRDOI:10042/27403

- ↑ Int D NMRDOI:10042/27404

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 L. Paquette et al., J. Am. Chem.Soc., 1990, 112, 277-283 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Paquette" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ J. H. Noordik and G. A. Jeffrey, Acta Cryst., 1977, B33, 403-408

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 K. Sarma et al., Tetrahedron: Asymmetry, 2009, 20, 1295-1300

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 P. C. Bulham Page et al., Tetrahedron, 2009, 65, 10, 2910-2915

- ↑ F. R. Jensen and R. C. Kiskis, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1975, 97, 5825-5831

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 T. Katsuki et al., Angewandte Chemie, 2012, 51, 8243-8246