Rep:Mod:LJK27

BH3

Calculation Method: B3LYP Basis set: 3-21G

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000217 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000105 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000919 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000441 0.001200 YES

Calculation method: B3LYP Basis set: 6-31G

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000203 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000098 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000867 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000415 0.001200 YES

Low frequencies --- -0.2260 -0.1035 -0.0054 48.0278 49.0875 49.0880 Low frequencies --- 1163.7224 1213.6715 1213.6741

The frequencies are outside the 15 cm-1 range but this was discussed with a demonstrator and deemed fine as the calculation converged.

BH3 |

IR Spectrum for BH3

| Vibrations (cm-1) | Intensity (arbitrary units) | Symmetry | IR active? | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1164 | 92 | A2" | Yes | Bend |

| 1214 | 14 | E' | Very slight | Bend |

| 1214 | 14 | E' | Very Slight | Bend |

| 2580 | 0 | A1' | No | Symmetric stretch |

| 2713 | 126 | E' | Yes | Asymmetric stretch |

| 2713 | 126 | E' | Yes | Asymmetric stretch |

The three vibrations at 1214 and at 1164 cm-1 are angle deformations because the angle around the bond is changing but the length of the bond stays the same. The three vibrations at 2713 and at 2580 cm-1 are bond stretches as the bond elongates and then retracts. The two 1214 cm-1, and two 2713 cm-1 vibrations are degenerate as they have the same wavenumber (which is proportional to the energy). The degenerate stretches appear as one peak in the spectrum which is why there are less than 6 peaks observed even though there are six vibrations. The symmetric stretch at 2580 cm-1 is IR inactive since there is no change in dipole moment, and therefore does not appear in the IR spectrum. Vibrations with very low intensity will not be experimentally observable. This includes 2580 cm-1 with an intensity of zero and the degenerate 1214 cm-1 angle deformations, with intensities of approximately 14 cm-1.

Smf115 (talk) 17:14, 28 May 2018 (BST)Correct assignments of the vibrational modes and symmetries and clearly explained answer.

Molecular Orbital Diagram for BH3

The real MO at the bottom left of the MO diagram is the bonding 1s boron MO.

The shaded negative phase in the LCAO MOs correspond to green regions in the real MOs, and unshaded positive phase to red regions. The real MOs appear to cover a larger surface area of the molecule than the LCAOs. For example, a1' in the LCAO doesn't suggest the delocalisation of this MO as can be seen in the real MO for a1'. However, the LCAO shows the composition of the MO more clearly and so it is useful in indicating which atomic orbitals are in combination in order to form that MO. The approximate shape of the LCAOs and real MOs are fairly similar, however there is less of a difference in shape between the s and p orbitals in the real MOs which can make it difficult to distinguish the real MOs; this is a benefit of the LCAOs.

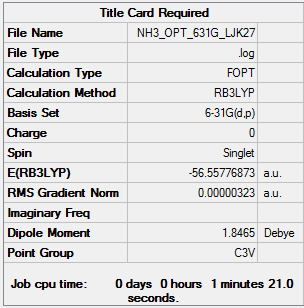

NH3

Calculation method: B3LYP Basis set: 6-31G

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000006 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000004 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000012 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000008 0.001200 YES

Low frequencies --- -34.7257 -34.7136 -21.3130 -0.0033 0.0071 0.0474 Low frequencies --- 1089.3593 1694.0550 1694.0553

NH3 |

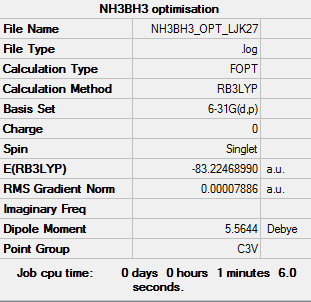

NH3BH3

Calculation method: B3LYP Basis set: 6-31G

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000207 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000079 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.001006 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000524 0.001200 YES

Low frequencies --- -0.0584 -0.0503 -0.0074 21.5681 21.5784 37.7476 Low frequencies --- 264.2274 631.7078 639.2561

NH3BH3 |

•E(NH3)= -56.55777 au •E(BH3)= -26.61532 au •E(NH3BH3)= -83.22469 au

ΔE=E(NH3BH3)-[E(NH3)+E(BH3)]= -0.05160 au (5dp) = -129 kJ/mol

B-N is a fairly strong dative bond. NH3BH3 is a solid at room temperature whereas analogous ethane is a gas which is due to ammonia-borane having a large dipole moment and ethane being non-polar.[1] The association energy for BH3CO is -90.5 kJ/mol which is less than NH3BH3's association energy which again supports B-N being a strong dative bond.[2] This is owing to the large difference in electronegativities of boron and nitrogen.

Smf115 (talk) 17:14, 28 May 2018 (BST)Correct calculation and nice second comprison to another dative bond. However, overall the B-N bond is relatively weak and a good comparison would be the C-C bond (which is the equivalent value for ethane) which is 348 kJ/mol [Atkins Physical Chemistry 8th edition DATA section Table 11.3b]

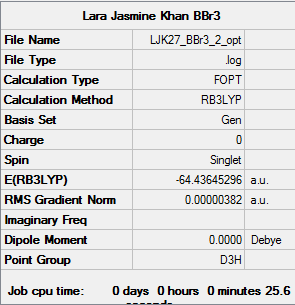

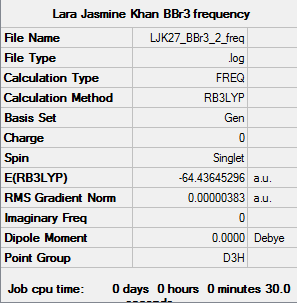

BBr3

Calculation method: B3LYP

Basis set: 6-31G

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000008 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000005 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000036 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000023 0.001200 YES

Low frequencies --- -0.0137 -0.0064 -0.0046 2.4315 2.4315 4.8421 Low frequencies --- 155.9631 155.9651 267.7052

BBr3 |

File:LJK27 BBr3 2 frequency.log

Aromaticity: Benzene and Borazine

Benzene

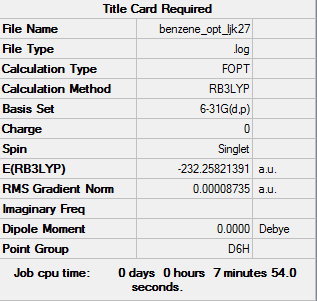

Calculation method: B3LYP

Basis set: 6-31G

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000198 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000076 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000812 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000283 0.001200 YES

Low frequencies --- -2.1456 -2.1456 -0.0089 -0.0043 -0.0043 10.4835 Low frequencies --- 413.9768 413.9768 621.1390

Benzene |

Borazine

Calculation method: B3LYP

Basis set: 6-31G

Item Value Threshold Converged? Maximum Force 0.000165 0.000450 YES RMS Force 0.000049 0.000300 YES Maximum Displacement 0.000409 0.001800 YES RMS Displacement 0.000128 0.001200 YES

Low frequencies --- -8.1143 -7.7640 -7.4910 -0.0099 -0.0082 0.1221 Low frequencies --- 289.0794 289.0902 403.3679

Borazine |

Charge Distribution

The images represent the charge distribution of benzene and borazine. The same colour range was used to visualise the charge intensity by corresponding to the pigment of the colour on the atoms. Borazine has more intense colours and thus more intense charge on the individual atoms. Benzene has a more even spread of charge with a value of +0.239 on the H atoms and -0.239 on the C atoms. The more electronegative atoms have a more negative value of charge located on them than the more electropositive atoms. Therefore, in borazine the N atom has a value of -1.102, +0.432 on H and +0.747 on B.

There is a greater difference in electronegativities in borazine than in benzene, and thus a less even spread of charge due to the alterating ring atoms in borazine. The electronegativity according to the Pauling scale is given as 2.04 for boron and 3.04 for nitrogen. Most of the charge located in borazine is located on ring atoms as can be seen in the image with the H atoms being much duller than the B and N atoms. B and N have a large difference in charge resulting in ionic character of bonds; all the ring atoms in benzene are carbon and so have an equal share of charge.

Similarly the H atoms attached to B atoms are less intense in charge than those attached to N atoms due to a greater difference in electronegativity between N and H compared to B and H.

Smf115 (talk) 15:26, 1 June 2018 (BST)Clear use of the same colour range to highlight the charge distributions across both of the molecules. Nice justification of the charge distributions due to electronegativities and to improve, consider other smaller factors, such as net charge and symmetry.

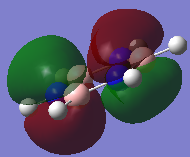

Molecular Orbitals for Benzene and Borazine

Smf115 (talk) 15:24, 1 June 2018 (BST)Good MO comparison and a nice range of MOs have been selected (15 and 14 especially!). The character of the MO is clearly identified however, further details like the main interactions, symmetry group of the orbital or whether the MO is pi- or sigma- type could be considered to develop the comparison further.

Concept of Aromaticity

Aromaticity was historically described by Kekule as resembling benzene. Properties associated with aromaticity are the intermediate lengths between single and double bonds between the ring atoms, for example in benzene the carbon-carbon bond lengths. There is an aromatic stabilisation energy which has been shown experimentally by comparisons to hydrogenation of cyclohexene to benzene. When placed in an applied magnetic field a pi ring current is induced and a magnetic field is induced by the ring current as a result of electron movements within orbitals, and there is resulting diamagnetic anisotropy. There is a difference in the field experienced by the protons; protons outside the ring experience low field and protons inside the ring experience high field. It is unfavourable for aromatics to lose there resonance stabilisation energy so in reactions with bromine water no decolourisation is observed.

The real MOs show the delocalisation and overlapping of orbitals when the phase is the same, as in MO17 above. The MOs lowest in energy have fewer nodes and greatest orbital overlap. This relates to the basic concept of aromaticity arising as a result of pz AO overlap.

The concept of overlapping pz AOs is a bad description for aromaticity. The pi-electron delocalisation was initially the explanation of aromatic stabilisation. However, there has been suggestion that the sigma electrons also have a role in aromatic stabilisation. The initial definition of aromaticity was for planar structures and the overlap of perpendicular p orbitals but it is now recognised that aromatic structures do not have to be planar.[3] Also aromaticity can be used to describe non-carbon structures such as metallic clusters where these associated properties are seen. Borazine can be described as weakly aromatic with a small ring current (indicating delocalisation), it obeys the 4n + 2 rule, and all BN bond lengths are equal. The (4n + 2) pi electron rule is used for indicating if something is aromatic. This is useful as the electronic structure is fundamental in determining the properties and ultimately aromaticity of a compound.[4]

References

Smf115 (talk) 15:26, 1 June 2018 (BST)Overall, a good wiki report with a very well attempted first section in particular.