Rep:Mod:LEM215TS

Year 3 Computational Lab: Transition Structures

Abstract

In this lab Gaussview was used to locate and characterize transition structures involved in various different pericyclic reactions. Two different computational electronic methods were used; PM6 (semi-empirical) and B3LYP/6-31G(p) (ab initio). Three different methodical approaches were introduced in a short tutorial:

- Method 1: Draw a guess TS followed by TS optimization

- Method 2: Draw a guess TS, freezing the atoms of reacting termini at approximate TS 'bond lengths' followed by TS optimization

- Method 3: Start with the optimized product, then work backwards to the TS by bond breaking and freezing atoms followed by TS optimization

Semi-empirical PM6 optimizations of molecular geometries to a minimum were generally faster but performed to a lower accuracy relative to density functional theory (DFT) B3LYP/6-31G(p) calculations. Therefore the geometries were optimized by PM6 initially and then, in some cases, by B3LYP/6-31G(p).

Introduction

Potential Energy Surfaces

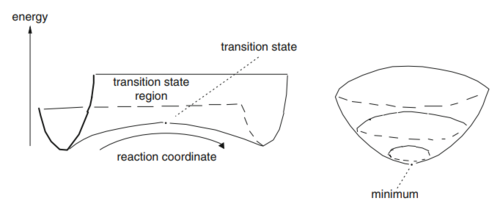

A potential energy surface (PES) is a key concept in computational chemistry which relates the energy of a molecule (or system of molecules) to its geometry.

For a non-linear molecule containing N atoms in a 3-dimensional space, there will be 3N-6 independent geometric variables associated with the bond lengths, bond angles and torsional angles [1]. There will be 3N cartesian coordinates for the set [x,y,z].

A minimum energy point on a potential energy surface is characterized as a stationary point, which is defined by a zero first order derivative [1]:

and

At any other point on the potential energy surface the reactive trajectory will 'roll' toward the region of lower potential energy [2]. This behavior is described by the relation:

The path followed by reactants from one minimum to the next must have sufficient energy to surmount an activation barrier, and pass through the transition state to reach the products. This lowest-energy pathway is known as the intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) [3].

The transition state (also a stationary point) linking two minima is a maximum along the IRC direction but a minimum in all other directions thus is often referred to as a saddle point [3]:

for all q, except the reaction coordinate, and

Nf710 (talk) 22:14, 8 February 2018 (UTC) nice diagrams, you can get this info about second derivatives by diagonalising the hessian.

Computational Methods

Computational methods are often used to help gain an understanding of the physical origins of experimental observations. Programs such as Gaussview employ a variety of electronic methods to carry out molecular simulations such as geometric minimizations, TS optimizations and IRC calculations for different types of chemical reactions.

PM6

The PM6 method is a self-consistent field (SCF) method, taking into account:

- electrostatic repulsion

- exchange stabilization

It requests a semi-empirical calculation using the PM6 Hamiltonian [4] and all calculated integrals are evaluated by approximate means. The method is based on the Hartree-Fock formalism [5], however PM6 makes many approximations such as zero differential overlap and obtain some parameters from empirical data leading to significant simplifications. As a result PM6 method is able to dramatically reduce computational cost whilst sacrificing the accuracy of potential energy surfaces.

B3LYP/6-31G(p)

B3LYP/6-31G(p) optimization is a density functional theory (DFT) method based on the idea of using only the density as the basic variable for describing many electron systems [6]. It is a formulation in terms of functionals of the density.

The B3LYP method is defined by the Lee, Yang, Parr (LYP) exchange-correlation functional [7]:

The exchange-correlation belonging to the B3LYP function involves the evaluation of the integrals via the Hartree-Frock (HF) method and local density approximation (LDA) and the Hamiltonian used is a function of position, r [7]. Since these calculations may be ran for highly dimensional systems, evaluation of the all integrals in the matrix can be very time consuming.

The difference in computing time using the B3LYP/6-31G(p) method was evident in exercise 2, where these optimizations took significantly longer than that using the PM6 level of optimization.

Nf710 (talk) 22:16, 8 February 2018 (UTC) Good understanding, this is the correct XC functional for B3LYP.

Reaction Types Investigated

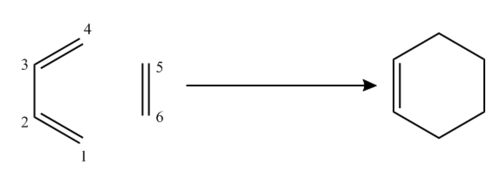

Diels-Alder Cycloaddition

A cycloaddition reaction generally involves the formation of a new ring and two new bonds from two reactants. To be concerted, there will only be one transition state that lies along the reaction coordinate between the reactants and the products. An example pericyclic reaction of this type is the Diels-Alder cycloaddition which involves the cycloaddition of alkenes to dienes and is commonly used as a method of forming substituted cyclohexenes [8]. These reactions have a relatively high level of predictability which can be determined by observing orbital symmetry relationships in the TS and reactants. In terms of the rules of orbital symmetry the 'allowed' Diels-Alder process is a concerted 4πs + 2πs cycloaddition.

Cheletropic Reaction

Cheletropic reactions are pericyclic cyclizations of two conjugated systems in which the two newly formed sigma bonds end on the same atom [9].

Exercise 1: Reaction of Butadiene with Ethylene

The reaction of butadiene and ethylene is an example of a concerted 4πS+2πS [4+2] cycloaddition.

The reactants, butadiene and ethylene, TS and product cyclohexene were optimized at the PM6 level. The optimizations were confirmed successful by running frequency calculations and by calculating the IRC for the TS. The output text files were also read to identify the optimization convergence.

MO Analysis

(Fv611 (talk) Good MO diagram, but be careful with ungerade/gerade labels. As you state, a centre of inversion is needed for those, and the transition state in this reaction doesn't have one.)

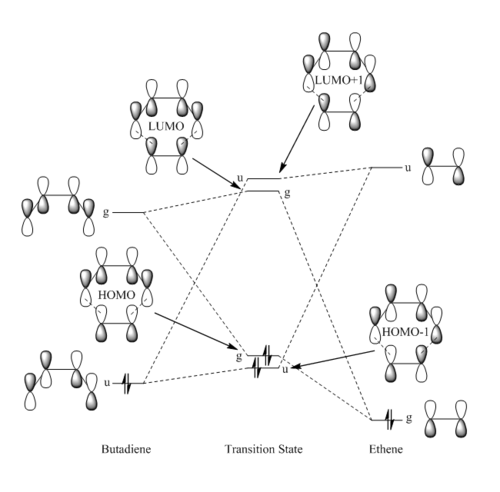

MO Diagram for the Formation of the Butadiene/Ethene TS

MO Visualization Using Gaussview Optimized Structures

|

| HOMO-1 | HOMO | LUMO | LUMO+1 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The MO diagram depicts the molecular orbitals involved in forming the transition state. The symmetry notation u and g is used to describe the molecular orbitals; gerade (symmetrical with respect to inversion) if the phase is the same and ungerade (asymmetrical with respect to inversion) if the phase changes.

According to perturbation theory [10] only orbitals of the same symmetry can interact to form the corresponding TS MOs. As a result the orbtial overlap integral is non-zero for symmetric-symmetric and antisymmetric-antisymmetric interactions and zero for symmetric-antisymmetric interactions (this interaction is disallowed).

In this Diels-Alder cycloaddition a pair of ungerade orbitals from butadiene and ethylene will interact to form bonding and anti-bonding combinations (as with the gerade orbitals). It is evident that it is the interaction of the gerade pair of orbtials which leads to the formation of the HOMO and LUMO of the transition state. Other orbitals of the same symmetry are too low/high in energy to allow orbital mixing.

Diels-Alder cycloadditions are classified as normal or inverse electron demand according to the relative energies of the interacting frontier molecular orbitals of the diene and dienophile [10]. By visualization of the generated MOs and correlation to their relative energies on the MO diagram, it is possible to classify this Diels-Alder cycloadditions as a normal electron demnand interaction since the greatest MO overlap occurs between the ungrade MOs (closest in energy).

Bond Length Analysis

(Fv611 (talk) Not sure why you wouldn't add the TS bond lengths for the c1-c6 and c4-c5 bonds in this table. Additionally, it would have been nice to explicitly compare the bond length of the bonds being formed at the TS with the average length of a single bond.)

| C-C Bonds | Bond Length (Å) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Butadiene/Ethene | Transition State | Cyclohexene | |

| C1-C2 | 1.3334 | 1.3797 | 1.5003 |

| C2-C3 | 1.4708 | 1.4112 | 1.3377 |

| C3-C4 | 1.3334 | 1.3798 | 1.5003 |

| C4-C5 | - | - | 1.5400 |

| C5-C6 | 1.3273 | 1.3818 | 1.5408 |

| C6-C1 | - | - | 1.5400 |

As the reaction progresses through the transition state to the product the double bonds in both reactants (C1-C2, C3-C4 and C5-C6) lengthen by an average of 15.3%. This is a result of the donation of electron density into π* orbitals which have anti bonding character thus weakening these bonds and leading to the formation of single C-C bonds. Conversely the single C-C bond in butadiene (C2-C3) gets shorter in length, reflecting the change in hybridization from sp3 to sp2.

In the transition state each C-C bond has a bond length intermediate between the reactants and the products since the bond breaking/bond forming process has begun. The Van der Waal radius of the carbon atom [11] is 1.70 Å and the C-C distance between the reacting termini in the PM6 optimized transition state is 2.11 Å. This distance is within two Van der Waal radii of carbon suggesting there is an interaction between each pair of carbons, C1-C6 & C4-C5, in the transition state.

| Hybridization of carbon center | Lit. Bond Lengths (Å) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Butadiene [12] | Ethene [13] | Cyclohexene [14] | |

| sp3 | 1.468 | - | 1.504, 1.515, 1.550 |

| sp2 | 1.348 | 1.330 | 1.335 |

By direct comparison to literature it can be seen that the single butadiene C-C bond length is overestimated whilst the remaining C-C bond lengths are underestimated by the PM6 level of optimization. This may be attributed to an underestimation in the effects of conjugation and hence electron delocalisation present in the butadiene molecule.

Vibrational Modes

The above .gif animation corresponds to the single negative frequency of the optimized structure, these are known as imaginary frequencies. The corresponding normal mode of vibration of an imaginary frequency will be along the reaction coordinate [15]. The vibration has a negative frequency as a result of a negative force constant in the following calculation:

By definition a structure with n imaginary frequencies corresponds to an nth order saddle point [16]. Therefore we can conclude that this structure is a first-order saddle point i.e. the transition state of the reaction. It is clear that the formation of the two bonds is synchronous since both ends of the reacting termini move toward one another whilst maintaining symmetry. The synchronous nature of bond formation can be confirmed by analysis of the IRC path which demonstrates the two bonds to form in the exact same frame.

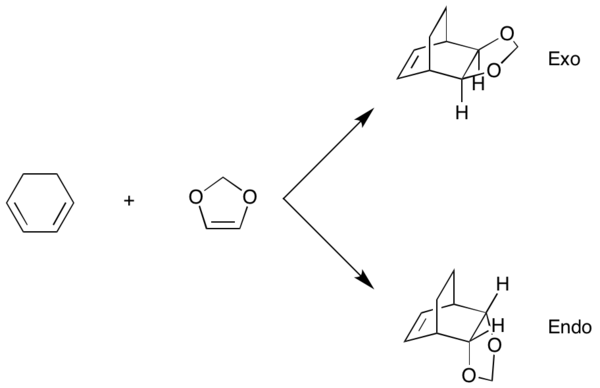

Exercise 2: Reaction of Cyclohexadiene and 1,3-Dioxole

The endo and exo transition states were located using method 2; the structures were first optimized by the PM6 method and then reoptimized with B3LYP/6-31G(d) to save computational time. The reactants, cyclohexadiene and 1,3-dioxole, and the endo and exo products were also optimized at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level. Frequency calculations confirmed the optimizations were successful; correct structures should have no imaginary frequencies for the reactants & products and a single imaginary frequency for the transition state.

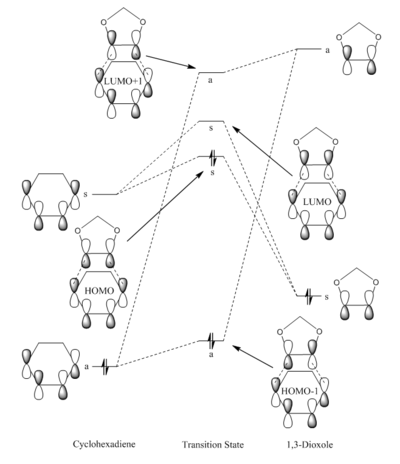

MO Analysis

MO Diagram for the Formation of the Cyclohexadiene/1,3-Dioxole TS

(Fv611 (talk) The MO diagram is good, but the position of your TS HOMO is off: you know its energy is -0.186 a.u., whereas that of the diene LUMO is -0.107. Additionally, there should have been a mention of the differences in MO relative energies between the endo and exo transition states.)

Single-point energy calculations were ran in Gaussview to determine the relative energies of the HOMO and LUMO FMOs for the B3LYP/6-31G(d) optimized 1,3-Dioxole and cyclohexadiene structures. Below shows the results:

| Reactant | Energy (a.u.) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| HOMO | LUMO | ||

| Cyclohexadiene | -0.20321 | -0.10722 | |

| 1,3-Dioxole | -0.19195 | 0.03770 | |

The MO diagram is closely related to that seen in exercise 1 as both reactions correspond to [4+2] cycloadditions, however the presence of electron donating oxygen atoms in the dienophile shifts the frontier molecular orbitals of 1,3-dioxole to a higher energy. As a result it is the the HOMO of the dienophile and LUMO of the diene which interact strongly to form the bonding HOMO and antibonding LUMO MOs of the transition state. Since these FMOs are closest in energy this interaction is the strongest interaction. As a result of this overlap the reaction can be classified as an inverse electron demand [4+2] cycloaddition. MO visualization of the HOMO of the B3LYP/6-31G(d) optimized endo and exo transition states show a larger contribution from the HOMO of the dienophile thus suggesting the HOMO of the dienophile is lower in energy relative to the LUMO of the diene.

Nf710 (talk) 22:23, 8 February 2018 (UTC) Excellent work here determining this.

The higher energy of the dienophile LUMO means that there is a smaller overlap with the HOMO of the diene (mismatch in energy) and so the interaction between this FMO pair is subsequently much weaker than that in exercise 1.

MO Visualization of Exo Transition State

| HOMO-1 | HOMO | LUMO | LUMO+1 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

MO Visualization of Endo Transition State

| HOMO-1 | HOMO | LUMO | LUMO+1 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Thermodynamics

Thermodynamic data from the .log files of the B3LYP optimized structures were used to calculated the energies and reaction barriers for the exo and endo reactions. The results are shown in the table below:

| Product | Energies (KJmol-1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Reaction Barrier | Reaction Energy | ||

| Exo | 164.55 | -66.85 | |

| Endo | 156.70 | -70.45 | |

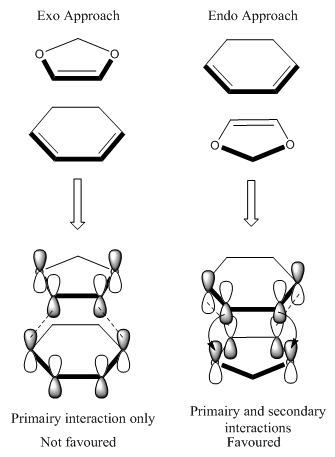

The formation of the endo transition state requires less energy than that required to form the exo transition state. This can be explained by considering the frontier molecular orbital interactions in the two transition states. In the endo transition state there is a secondary orbital interaction, in addition to the primary interaction, between the p-orbitals of the oxozole and the π-system of cyclohexadiene. This stabilizing interaction reduces the energy of the endo transition state hence leads to the lowering of the activation energy barrier. As a result it is clear that the corresponding endo product is kinetically favuorable over the exo product, since there are only primary interactions in the exo transition state. This means that for an irreversible Diels-Alder the major product formed will be the endo product.

By comparison of the reaction energies, it can be concluded that the exo product is thermodynamically favoured since there is a smaller reaction energy associated with this pathway. Therefore for a Diels-Alder reaction which is allowed to equilibrate, then major product would be the exo product.

Nf710 (talk) 22:24, 8 February 2018 (UTC) Your energies are correct and you have come to the correct conclusions well donw.

Exercise 3: Diels-Alder vs Cheletropic

(Don't forget that double bond in the second set of DA reactions Tam10 (talk) 15:02, 31 January 2018 (UTC))

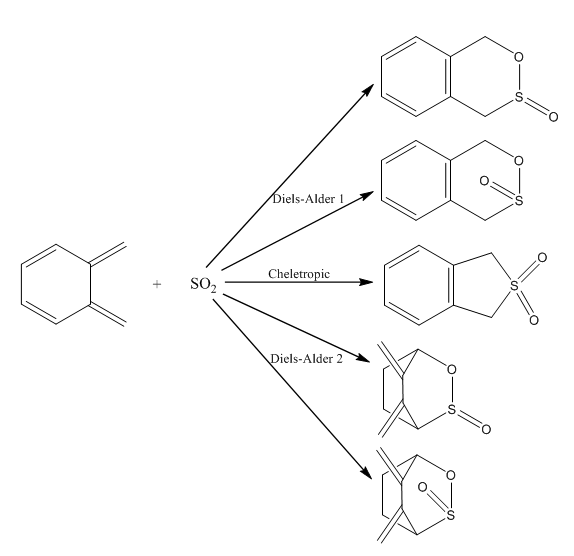

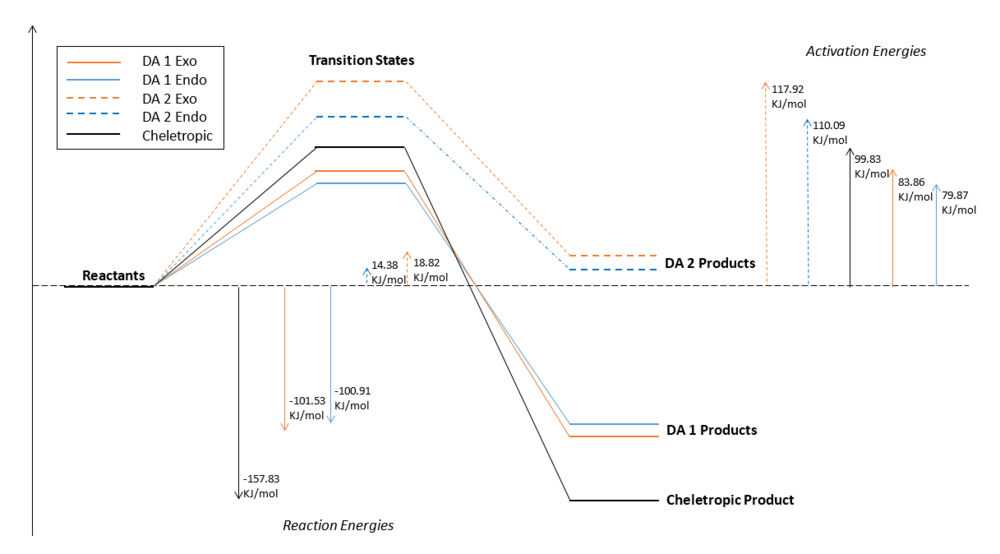

In this exercise three different reaction paths were investigated between o-xylylene and sulfur dioxide. For the two Diels-Alder reactions the endo and exo approaches were both tested whilst the cheletropic reaction produces only a single product. As for exercise 2, the energies and activation barriers were calculated from the .log files of all the PM6 optimized structures. From this data it was possible to compare and determine the relative stability of these reactions.

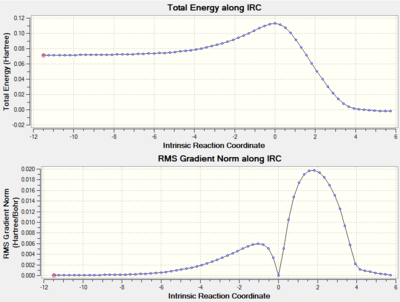

Calculated IRC Paths

Diels-Alder 1 Endo Approach

Diels-Alder 1 Exo Approach

Diels-Alder 2 Endo Approach

Diels-Alder 2 Exo Approach

Cheletropic Reaction

(Looks like you're missing hydrogens in the DA 2 Exo TS. Fortunately it's only for the IRC so you still have the correct results later on Tam10 (talk) 15:02, 31 January 2018 (UTC))

The .gif files of the IRC animations for each reaction are shown above. It is clear that the cheletropic reaction is synchronous, whereas the Diels-Alder reaction (for both endo and exo approaches) is asynchronous, i.e. the oxygen atom appears to form a C-O bond before the sulfur participates in bonding. Below are the corresponding .log files.

(You won't really be able to tell which bond forms first as it's impossible to define "when" a bond has formed. Gaussview uses cutoffs to decide when to draw a bond Tam10 (talk) 15:02, 31 January 2018 (UTC))

| Reaction Type and Structure | Files | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| IRC .log File | |||

| DA 1 Endo | File:DA PRODUCTOPT ENDO TS2 IRC.LOG | ||

| DA 1 Exo | File:DA PRODUCTOPT EXO TS2 IRC2.LOG | ||

| DA 2 Exo | File:DA2 PRODUCTOPT EXO TS2 IRC.LOG | ||

| DA 2 Endo | File:DA2 PRODUCTOPT ENDO TS2 IRC.LOG | ||

| Cheletropic | File:CH TS IRC.LOG | ||

Thermodynamics

Thermodynamic data from the .log files of the PM6 optimized structures were used to calculated the energies and reaction barriers for the exo and endo DA reactions and the cheletropic reaction. The results are shown in the table below.

| Reaction Type | Energies (KJmol-1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Reaction Barrier | Reaction Energy | ||

| DA 1 Exo | 83.86 | -101.53 | |

| DA 1 Endo | 79.87 | -100.91 | |

| DA 2 Exo | 117.92 | 18.82 | |

| DA 2 Endo | 110.09 | 14.38 | |

| Cheletropic | 99.83 | -157.83 | |

| Reaction Type and Structure | Files | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Product .log file | Transition State .log file link | ||

| DA 1 Exo | File:EXO PROD OPT LEM215.LOG | File:EXO PROD TS2 LEM215.LOG | |

| DA 1 Endo | File:DA PRODUCTOPT ENDO.LOG | File:DA PRODUCTOPT ENDO TS2.LOG | |

| DA 2 Exo | File:EXO PROD LEM215.LOG | File:EXO TS OPT LEM215.LOG | |

| DA 2 Endo | File:ENDOPROD OPT LEM215.LOG | File:ENDOPROD OPT TS2.LOG | |

| Cheletropic | File:CH PRODUCTOPT.LOG | File:C TS2.LOG | |

Diels-Alder 1

The results for the DA 1 pathway clearly indicate the endo product is the kinetic product, since it has the lowest activation energy, and the exo product to be the thermodynamic product. Once again the stabilization of the endo transition state and hence activation energy barrier can be attributed to secondary orbital effects which are not present in the exo transition state. The formation of either product can be favoured by altering the reaction conditions i.e allow the reaction to be irreversible (kinetic conditions) or allow an equilibration (thermodynamic conditions).

Cheletropic Reaction vs Diels-Alder

However when considering all possible pericyclic reaction pathways, the cheletropic product appears the be the most thermodynamically favourable since this has the lowest reaction energy. This could be explained by the difference in the bond energies involved in the different reactions. The cheletropic reaction differs from the DA reaction as it involves the formation of two C-S single bonds whereas the DA process involves the breaking of a single S-O and formation of single C-O and C-S bonds. The combined energy of C-S and S=O is much greater than the combined energy of single C-O and C-S bonds [17]. The presence of an additional strong sulfonyl group provides a larger enthalpic contribution thus gives the cheletropic product its thermodynamic stability. The cheletropic reaction has the highest activation energy barrier due to the formation of a highly strained five-membered ring, which has a C-S-C bond angle of approximately 93.4o [17], compared to a strain-free six-membered ring.

Diels-Alder at the Alternative Diene Site

Xylylene can undergo a second Diels-Alder cycloaddition at the other cis-butadiene moiety present in the molecule (DA 2). The calculated thermodynamic data suggests that this reaction pathway requires an input of energy, i.e is endothermic, since the formation of both exo and endo products have positive reaction energies. Both exo and endo approaches also have higher activation energy barriers than the DA at terminal diene site (DA 1). These products are unable to form the highly stable aromatic system seen in DA 1 thus are not stabilised. As a result a Diels-Alder cycloaddition at this site is highly kinetically and thermodynamically unfavourable.

Xylylene Instability

Xylylene is highly unstable, the DA 1 and cheletropic cycloadditions are thermodynamically driven by the formation of a highly stabilised aromatic system. This is evident in the calculated IRC paths, which show the formation of the six-membered aromatic ring occurs prior to the bonding to sulfur and oxygen.

Reaction Profile

The reaction profile below directly compares the energies associated with each pericylic reaction.

(Nice diagram including all explored reactions. To save words/space, you can write "Energy (kJ/mol)" on the energy axis. It is also more common to see the axis labelled than each data point Tam10 (talk) 15:02, 31 January 2018 (UTC))

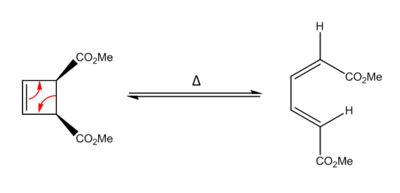

Further Work: Electrocyclic Ring Opening of a Cyclobutene

Theory of Electrocyclic Reactions

An electrocyclic reaction is a type of pericyclic rearrangement which involves a concerted cyclization of a conjugated π-electron system by the conversion of a π-bond to a ring forming σ-bond or the reverse (electrocyclic ring opening).

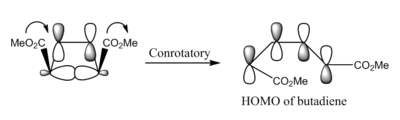

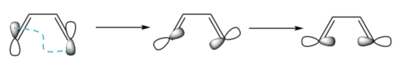

Woodward and Hoffmann suggested that the stereochemistry of electrocyclic ring opening reactions is controlled by the symmetry properties of the HOMO of the open-chain conjugated system [18], i.e the substituted acyclic butadiene (in this reaction), as well as by FMO theory. Electrocyclic reactions cause a stereochemical alteration at the reacting termini atoms via a rotational process [19]. These reactions are classified according to this rotational process; if the terminal atoms (or groups) rotate in the same direction it is known as conrotation whereas if they rotate in opposite directions it is called disrotation.

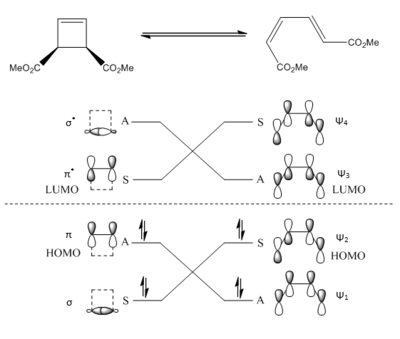

Electrocyclic Reaction Classification and Correlation Diagrams

Thermally this reaction undergoes a controtation as it is a 4nπe conjugated system and so must react antrafacially [20]. The reverse reaction, the electrocyclic ring closure of the disubstituted butadiene to the disubstituted cyclobutene is thermodynamically unfavourbale since the diene has a greater stability by approximately 50 KJmol1 [20], as the formation of a highly strained four-membered ring requires a large input of energy.

Correlation diagrams are often used to predict whether an electrocyclic reaction is allowed or disallowed by considering the symmetry properties of the reactant and product MOs.

(Nice diagrams, but they look suspiciously like the wikipedia article... Tam10 (talk) 15:15, 31 January 2018 (UTC))

A disubstituted cyclobutene reactant is a 4nπe conjugated system, thus for a ground state/thermal electrocyclic ring opening, the HOMO of the open-chain conjugated product will be Ψ2. This is because this MO contains the fewest nodes (only one) and so produces the lowest energy transition state (in accordance with Mobius topology as per perturbation molecular orbital theory (FMO) [19]). This is illustrated by the correlation diagram depicted in figure 11 above.

Gaussview Optimization of the Electrocyclic Ring-Opening

The reactant, Mobius aromatic TS and product corresponding to the ground state/thermal reaction were optimized at the PM6-level in Gaussview. And the IRC path was calculated from the PM6-optimized TS.

MO Analysis

| PM6-Optimized Structure | HOMO | LUMO | ||||

| Disubstituted Cyclobutene | ||||||

| Transition State | ||||||

| Disubstituted Acyclic Butadiene |

The HOMO orbitals depicted in the table above display the expected conrotation during the electrocyclic ring-opening/closing. The HOMO of the disubstituted butadiene is antisymmetric and therefore to a allow an in-phase MO overlap, the termini groups must undergo a conrotation. The transition state HOMO represents a Mobius aromatic transition state and there is a strong 'end-on' overlap of MOS in the disubstituted cyclobutene. The strong end-on MO overlap indicates the formation of a strong σ-bond between the termini atoms.

Calculated IRC Path

The electrocyclic ring-opening is clearly illustrated by the IRC path calculated from the PM6-optimized transition state, and the conrotatory motion of the two ester groups is observed.

Thermodynamics

| Structure | Energy (KJmol-1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies | |||

| Disubstituted Cyclobutene | -260.59 | ||

| Transition State | -100.49 | ||

| Disubstituted Acyclic Butadiene | -298.03 | ||

Electrocyclic ring-opening reaction barrier = 160.10 KJmol-1 Electrocyclic ring-closing reaction barrier = 197.54 KJmol-1

Reaction Energy = -37.44 KJmol-1

| Structure | Files | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| .log File Links | |||

| Disubstituted Cyclobutene | File:REACTANT OPT PM6 LEM215.LOG | ||

| Transition State | File:TS OPT MO LEM215.LOG | ||

| Disubstituted Acyclic Butadiene | File:PRODUCT OPT PM6 LEM215.LOG | ||

The calculated thermochemistry data suggests the forward electrocyclic ring-opening of the disubstituted cyclobutene is exothermic (negative reaction energy). The activation energy barrier for the electrocyclic ring-opening direction is approximately 18.95% smaller than that for the corresponding reverse ring-closing indicating the forward reaction is thermodynamically favoured. The greater stability of the butadiene is reflected in the calculated energy of the optimised structures; calculated to be 37.44 KJmol-1 more stable than the cyclobutene.

(+6%)

Conclusion

In conclusion, two levels of electronic methods were used to predict the feasibility of a variety of pericyclic reactions. The PM6-level of optimization was efficient at obtaining rapid qualitative results for the reactants and products. However, appeared to be insufficient for the transition state calculations and thus a further optimisation using the B3LYP/6-31G(d) method was required to obtain adequate results.

The Diels-Alder reactions were classified as normal or inverse electron demand by visualisation of the MOs and the construction of MO diagrams showed the importance of MO symmetry relationships in allowed and forbidden pericyclic reactions.

IRC calculations of the transition state were carried out to animate the reactions and determine whether the bond breaking/forming processes were synchronous or asynchronous and thermochemistry calculations allowed the identification of thermodynamically and kinetically favoured pericyclic reaction pathways.

For the electrocyclic ring-opening reaction it was possible to visualise the observed torquoselectivity by Gaussview optimisations and calculations. MO correlation diagrams and analyses clearly demonstrated why the process must be conrotatory to be thermally allowed.

References:

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Chapter 1. Computational Quantum Chemistry. (n.d.). Theoretical and Computational Chemistry Series, pp.17-22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1039/9781849737289-00001

- ↑ Doye, J. and Wales, D. (1996). On potential energy surfaces and relaxation to the global minimum. The Journal of Chemical Physics, 105(18), pp.8428-8445. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.472697

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Lewars, E. (2010). The Concept of the Potential Energy Surface. Computational Chemistry, pp.13-20. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-3862-3_2

- ↑ Gaussview Online Manual. http://gaussian.com/semiempirical

- ↑ Cramer, C. (2014). Essentials of computational chemistry. Chichester [u.a.]: Wiley, pp.131-151. ISBN 0-470-09181-9

- ↑ U von Barth (2004). Basic density-functional theory. Phys. Scr. T109, pp.9-39.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 C., Yang, W. and Parr, R. (1988). Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Physical Review B, 37(2), pp.785-789. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.37.785

- ↑ Carey, F. and Sundberg, R. (2007). Advanced Organic Chemistry Part B: Reactions and Synthesis. 5th ed. New York: Springer, p.474. ISBN 978-0-387-44899-2

- ↑ Nguyên, T. (2007). Frontier orbitals. Chichester, England ; Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, p.72. ISBN 978-0-471-97358-4

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Kobayashi, S. and Jørgensen, K. (2002). Cycloaddition reactions in organic synthesis. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH, p.314.

- ↑ Batsanov, S.S. Inorganic Materials (2001) 37: 871. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011625728803

- ↑ Kveseth, K.; Seip, R.; Kohl, D. Acta Chem. Scand. A 1980, 34, 31-42.

- ↑ Harmony, M. D. In Vibrational Spectra and Structure; Durig, J. M., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2000; Vol. 24, Chapter 1

- ↑ Chiang, J. and Bauer, S. (1969). Molecular structure of cyclohexene. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 91(8), pp.1898-1901. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja01036a004

- ↑ Dokholyan, N. (2012). Computational Modeling of Biological Systems. Boston, MA: Springer US, p.131.

- ↑ Ramachandran, K., Gopakumar, D. and Namboori, K. (2008). Computational Chemistry and Molecular Modeling. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, p.245.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Doi, J. (1992). Organic Sulfur Chemistry: Structure and Mechanism. 1st ed. Boston: CRC Press, pp.3-4,6. ISBN 0-8493-4739-4

- ↑ Turro, N. (1991). Modern molecular photochemistry. Mill Valley: University Science Books, p.495

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Oae, S. and Marvell, E. (1980). Thermal Electrocyclic Reactions. 1st ed. London: Academic Press Inc., pp.3-5. ISBN 0-12-476250-6

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Nasipuri, D. (1994). Stereochemistry of Organic Compounds: Principles and Applications. 2nd ed. Kharagpur, India: New Age International (P) Ltd., p.451. ISBN 81-224-0570-3