Rep:Mod:Joh13

The following computational experiment explored the structure of transition states in two pericyclic reactions, the Cope Rearrangement and the Diels-Alder Cycloaddition. Structural and MO analysis was undertaken to rationalise different energies obtained.

The optimisations and modelling of transition states was done using Gaussview 5.0.9. The software solves the Schrodinger Equation numerically by the spacial placement of atoms and electrons to generate a potential energy surface.

All the .log files for the experiment can be located here.

The Cope Rearrangement Tutorial

Optimising Reactants and Products

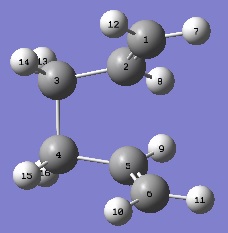

The Cope rearrangement is a [3,3]-sigmatropic shift organic pericyclic reaction, performed on 1,5-hexadiene. The reaction has a concerted mechanism, which can proceed through either a chair or a boat conformation.[1] These transition structures were analysed to both find the lowest energy transition state (i.e. the most probable) and prove the reaction's concerted nature.

Due to the fact that the hexadiene molecule can freely rotate around the C-C single bonds, it can form different structures of both the gauche (synperiplanar) and anti (antiperiplanar) conformers.To begin with, computational analysis was done on various structures of the 1,5-hexadiene molecule to view their relative energies. This was done using two different methods, Hartee-Fock 3-21G and Differential Functional Theory 6-31G*.

Optimising 1,5-Hexadiene Antiperiplanar Conformer

The hexadiene molecule was drawn in Gaussview with an anti linkage across the C3-C4 bond. The molecule was cleaned, and then optimised under the Hartree-Fock 3-21G method. The resultant molecule had an energy of -231.69260234 a.u., and a point group of C2. This corresponds to the anti1 conformer from Appendix 1. [2]

| Molecule | Data Summary | Point Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

C2 |

Optimising 1,5-Hexadiene Synperiplanar Conformer

The hexadiene molecule was drawn in Gaussview with a gauche linkage across the C3-C4 bond. The molecule was cleaned, and then optimised under the Hartree-Fock 3-21G method. The resultant molecule had an energy of -231.68916019 a.u., and a point group of C1. This corresponds to the gauche6 conformer from Appendix 1. The energy obtained is higher than that of the anti1 conformer obtained above. This can be attributed to the greater steric interactions of the larger vinyl groups, which is much less pronounced in the antiperiplanar conformers.

| Molecule | Data Summary | Point group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

C1 |

Optimising 1,5-Hexadiene Lowest Energy Conformer

Initially one might think that the anti1 structure obtained above would be the lowest energy conformer of the hexadiene molecule based on steric considerations, however the structure corresponding to gauche3, when drawn in Gaussview, cleaned, and then optimised under the Hartree-Fock 3-21G method produced the lowest energy of -231.69266120 a.u. . The molecule has a point group of C1, and the results are summarised in the table below.

| Molecule | Data Summary | Point group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

C1 |

In order to understand why this conformer has an unexpected lower energy, stereoelectronic effects of secondary orbital overlap must be considered. When viewing the HOMO of the molecule, shown on the right, a favourable π orbital interaction between the two vinyl groups. This allows for some electron delocalisation, leading to an overall lower energy.

Nf710 (talk) 16:15, 20 January 2016 (UTC) Good use of orbitals to explain the ordering

Optimising 1,5-Hexadiene Anti2 Conformer

The anti2 structure of the hexadiene molecule was drawn in Gaussview, cleaned, and then optimised under the Hartee Fock 3-21G method. This gave an energy of -231.69253528 a.u. and a point group of Ci. The resultant optimisation was re-run under the Differential Functional Theory 6-31G* method, giving an energy if -234.61171063 a.u. and a point group of Ci. The results are summarised in the table below.

| Hartee Fock Molecule | Hartree Fock Data Summary | DFT Molecule | DFT Data Summary | Point group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Ci |

The DFT method is a more thorough optimisation, as it takes into account both the spin and the pairing energy of the electrons in the molecule. This is not calculated in the Hartree-Fock method, which approximates using a single Slater Determinant, meaning that electron-electron interactions are ignored. Although this can be costly for a large system, the hexadiene example is adequately small to be run under this method.[3] The absolute energies of the Hartree Fock and DFT method cannot be compared, but a table summarising differences in C-C bond angles and lengths is shown below. Only half of the bond distances and angles are taken due to the centre of inversion present in the Ci point group.

| Bond Angles (°) | Bond Lengths (Å) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optimisation | C1-C2-C3 | C2-C3-C4 | C1-C2-C3-C4 | C2-C3-C4-C5 | C1-C2 | C2-C3 | C3-C4 |

| Hartree Fock | 124.8 | 111.3 | 114.7 | 180.0 | 1.316 | 1.509 | 1.553 |

| DFT | 125.3 | 112.7 | 118.6 | 180.0 | 1.334 | 1.504 | 1.548 |

Although both methods have very small differences in bond angles and lengths (indicating both methods have adequately identified the potential energy minimum), the DFT basis set has slightly larger bond angles and C-C double bonds, but smaller C-C single bonds.

Frequency Analysis at 298.15 K

A frequency calculation was run on the anti2 structure at the DFT 6-31G* theory level. This not only allows us to determine whether the structure is a transition state, but also obtains absolute energy values that are comparable to experimentally obtained values.

By looking at the obtained frequencies, it can be seen that all of the vibrations are positive. This indicates that the molecule is not at a transition state, which would show a negative "imaginary" frequency.

The thermochemical data must be looked at to calculate absolute energy values. The data is summarised in the following table:

| Thermochemical Significance | Energy (a.u.) |

|---|---|

| Sum of electronic and zero-point energies | -234.469219 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal energies | -234.461869 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal enthalpies | -234.460925 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal free energies | -234.500809 |

The sum of electronic and zero-point energies is calculated at 0 K. The sum of electronic and thermal energies is calculated at 298.15 K, which inclued rotational, vibrational and translational energies. When calculating the thermal enthalpy, the RT term from H = E + RT is considered. At 298.15 K, the contribution from RT is significant, hence a higher energy is obtained (at 0 K the term due to RT should be 0, and so the third and first row of the table would have equal energies). The final value in the table, the free energy, takes into account the entropy of the system using the equation G = H - TS. As this calculation is performed at constant pressure (1.0 atm), H will increase as temperature increases to compensate.

Optimising "Chair" and "Boat" Transition Structures

The Cope rearrangement was analysed by considering two possible reaction transition states, known as the "chair" and "boat" conformations. These structures were optimised by different methods. To calculate the activation energies of the Cope Rearrangement for each transition state, the Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate pathway was analysed.

Chair Optimisation via Force Constant Calculation

To generate a guess structure of the chair conformation, two allyl fragments were optimised under the Hartree Fock 3-21G basis set, and then orientated into a rudimentary chair formation. The two formed C-C bonds between the allyl fragments were set at about 2.2 Å, and the molecules symmetrised. An optimisation and frequency calculation was run under Hartree Fock 3-21G with the TS(Berny) method, setting the method to calculate the force constant once. The additional keywords Opt=NoEigen were added to prevent Gaussian from crashing if it generated more than one imaginary frequency. The resultant optimisation had a single negative frequency at -817.94 cm-1, with the vibration shown in the table below. The energy of the transition state was found to be -231.61402207 a.u., and the bond lengths of the formed C-C bonds to be 2.02038 Å. The fact that a single imaginary frequency is indicative of a transition state can be better understood by first considering the 1-D quantum harmonic oscillator, which contains the force constant k in the term (k/m)-0.5. With a negative force constant, an imaginary frequency is generated. The force constant k can be found from the Hessian, or the force constant matrix, which is the second derivative of the potential energy surface (PES)[4]. As a transition state corresponds to a saddle point on the reaction potential energy surface, this generates a negative force constant, and therefore a single imaginary frequency.

| Optimised Chair | Results Summary | Imaginary Frequency Animation | Frequency Summary | Point group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

C2h |

Nf710 (talk) 16:30, 20 January 2016 (UTC) 1 imaginary freq = 1 maximum in one degree of freedom. good explanation, you could have used a proper equation.

Chair Optimisation via Freeze-Coordinate Method

The chair transition structure was then optimised via a different method, known as the frozen co-ordinate method. The two optimised allyl fragments were once again placed at a distance of about 2.2 Å and symmetrised. Using the redundant co-ordinate editor, the distances between the formed C-C bonds were frozen, and the molecule optimised under the Hartree Fock 3-21G method. Then, using the redundant co-ordinate editor to set the previously frozen bonds to derivative, the molecule was optimised under the same basis set using a TS(Berny) optimisation. The results are summarised in the table below.

| Optimised Chair | Results Summary | Imaginary Frequency Animation | Frequency Summary | Point group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

C2h |

When comparing the result of the frozen co-ordinate optimisation method to the force constant method, it can be seen that the energies are almost identical, differing only at the seventh decimal place. The imaginary frequencies of -817.94 cm-1 and -817.84 cm-1 are extremely close, and the bond lengths differ by 0.00005 Å. Therefore it can be stated that both methods adequately produce the optimised chair transition state.

Boat Optimisation via QST2 Method

The second transition state looked at was the "boat" conformer. To begin with, the QST2 method was used to produce the optimised structure. This method required the reactant and product molecule to be drawn, allowing Gaussian to predict the intermediate transition state. This was initially done as shown below, resulting in an incorrect transition structure. It can be seen that the structure more closely resembles the chair, and the C-C bonds are twisted and 3.14645 Å apart, which is much longer than the previous TS length.

| Reactant | Product | Boat Transition Structure | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

To try and obtain a more accurate estimation of the boat transition state, the reactant and product molecule were reorientated into a position that more closely resembled the "boat" structure. This was done by setting the central dihedral angle of the molecule at 0°, and the angles C2-C3-C4 and C3-C4-C5 to 100°. When the optimisation was run again, the transition structure below was obtained. Not only can it be seen just by eye that the structure looks like the desired "boat", but the C-C bond distances of 2.14075 Å are much more appropriate. The energy of the boat was found to be -231.60280200, and the imaginary frequency indicative of a transition state was found to be -839.94.

| Reactant | Product | Boat Transition Structure | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Boat Optimisation via QST3 Method

The boat transition was attempted to be found via a modification to the QST2 method. For the QST3 method a guess structure of the boat transition structure is used alongside the reactant and product molecule. This can theoretically produce a more reliable model from non-specifically orientated reactant and product molecules. A guess structure of the "boat" conformation was constructed, and the optimisation run under Hartree Fock 3-21G TS(QST3) method. The resultant structure is shown below, along with the energy of -231.68944096 a.u.

| QST3 Transition Structure | Energy Summary | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

The QST3 method did not generate an adequate representation of the boat transition state. This can be attributed to the large disparity in reactant and product molecule structure, which was the same issue found in the initial QST2 run. No further molecule reorientation was performed to improve the result of the QST3 method, as this would lead to unnecessary work when the QST2 produced an adequate result.

Nf710 (talk) 16:36, 20 January 2016 (UTC) Correct frequncies

Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate of Transition Structures

In order to view the reaction pathway from transition structure to reactant or product an intrinsic reaction pathway can be used. This enables identification of the reactant and product conformers that form the transition state. The optimised structure of the chair via the force constant calculation was taken and an IRC calculation was run. Although the IRC was selceted to run 50 steps, the calculation failed after 44 steps. However, by looking at the plot of RMS gradient reaching 0, it can be seen that a local energy minima had already been reached. The energy obtained, -231.69166702 a.u., when compared to Appendix 1 indicates that the molecule is gauche2. This can be confirmed by checking its point group, which is in agreement as C2.

Nf710 (talk) 16:43, 20 January 2016 (UTC) Correct conformer obtained

| IRC Graph | Reaction Animation |

|---|---|

|

|

Activation Energies of Transition Structures

To calculate the activation energies of the chair and boat conformers, the two transitions states and the anti2 conformer of the reactant were optimised to the higher basis set of DFT 6-31G*. However, the original Hartree-Fock optimised structures were used to minimise the time of computation. To compare the effect of the higher level of computation, various geometric parameters of the two different optimisations are compared below for the transition states. The Intermolecular distance refers to the distance between adjacent carbons on each allyl fragment, whilst intramolecular distance refers to the distance between adjacent carbons on one allyl fragment.

| Basis Set | Boat | Chair | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intermolecular C-C Distance (Å) | Intramolecular C-C Distance (Å) | Intermolecular C-C Distance (Å) | Intramolecular C-C Distance (Å) | |

| 3-21G | 2.14075 | 1.38133 | 2.02043 | 1.38928 |

| 6-31G* | 2.20653 | 1.39326 | 1.96766 | 1.40750 |

The geometrical values are very similar for both levels of calculation. Therefore it can be said that both calculations have adequately produced an accurate structure of the transition states. Due to this similarity, the activation energies for both basis sets were calculated to see which method produced a value closer to literature. The various energies of each molecule are summarised in the table below.

| 3-21G | 6-31G* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chair | Boat | Anti2 | Chair | Boat | Anti2 | |

| Electronic Energy (a.u.) | -231.619233 | -231.602802 | -231.692535 | -234.556931 | -234.543093 | -234.611711 |

| Sum of Electronic and Zero Point Energies (a.u.) | -231.466700 | -231.450929 | -231.539539 | -234.414930 | -234.402340 | -234.469219 |

| Sum of Electronic and Thermal Energies (a.u.) | -231.461341 | -231.445299 | -231.532565 | -234.409010 | -234.396005 | -234.461869 |

From these values we can calculate the activation energies at 0 K from the difference in the sum of electronic and zero point energies, and at 298.15 K from the difference in the sum of electronic and thermal energies. These values are used instead of simply the electronic energies as they include the effect of rotational and vibrational energies at the different temperatures.

| Unit of Energy | Basis Set | Boat | Chair | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 K | 298.15 K | 0 K | 298.15 K | ||

| a.u. | 3-21G | 0.088610 | 0.087266 | 0.072839 | 0.071309 |

| 6-31G* | 0.066879 | 0.065864 | 0.054289 | 0.052859 | |

| kJmol-1 | 3-21G | 232.65 | 229.12 | 191.24 | 187.22 |

| 6-31G* | 175.59 | 172.93 | 142.54 | 138.78 | |

By looking at the table, it can be seen that the 3-21G method produces larger activation energies than that by the 6-31G* method. Also, the difference obtained by changing the basis set is greater than that obtained by increasing the temperature. However, both methods show that the chair structure is lower in energy that the boat structure. In order to compare to literature values, the results were converted from a.u. to kJmol-1 (1 a.u. = 2625.5 kJmol-1). Literature values for the room temperature activation energies of the boat and chair structures were found to be 140.16 ± 2.09 and 187.02 ± 8.37 respectively.[5] Compared to the computed values, the DFT 6-31G* method provided the more accurate approximation. In conclusion, both methods are adequate to provide the structural information for the transition state of the reaction, but if estimates for the activation energy of the transition states are needed, then it is better to use the 6-31G* basis set.

Nf710 (talk) 16:48, 20 January 2016 (UTC) your energies are correct. This is a well done report you have done everything that has been asked of you. However you could have shown a better understanding of the methods used.

The Diels Alder Cycloaddition

The Diels Alder reaction is a concerted pericyclic [4+2] addition of a diene and a dienophile. The transition state is cyclic, with the creation of 2 σ bonds and destruction of 2 π bonds. This acts as a driving force for the reaction as σ bonds are stronger than π bonds.[6] The reaction can be carried out with either normal or inverse electron demand. When looking at normal electron demand, the reaction becomes more favourable by making the diene more electron rich and making the dienophile electron poor. This can be explained by considering the orbitals of the two reactants. By placing electron donating groups on the diene, the energy of its HOMO is raised, whilst placing electron donating groups on the dienophile lowers the energy of its LUMO. By decreasing the HOMO - LUMO gap, the reaction becomes more facile. In the case of inverse electron demand, the HOMO of the dieneophile is considered along with the LUMO of the diene. Therefore, to decrease the energy gap and improve the efficacy of the reaction, the electron donating and withdrawing groups are placed on the opposite reactants.

By considering stereoelectronics, predictions can be made on the product structure. This was explored in the second part of the exercise in the reaction of cyclohexa-1,3-diene with maleic anhydride. However, the transition state of a [4+2] pericyclic reaction was first more simply modeled using cis butene and ethene.

For the entire exercise, the AM1 semi-empirical molecular orbital method was used for calculations. Compared to previously-used methods (Hartree Fock and DFT), the semi-empirical method is a faster, less accurate calculation as it omits various integrals. This was necessary for the exercise as the molecules analysed are more complex and so would be expensive to run on a higher level of theory.

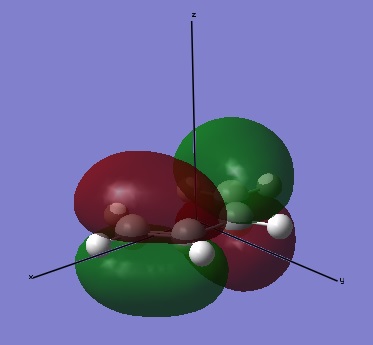

The Reaction of Cis Butene with Ethene

The molecules of cis butene and ethene was drawn in Gaussview, cleaned, and then optimised. The resulting cis butene had C2v symmetry and an energy of 0.04879719 a.u. . When looking at the HOMO and LUMO, it can be seen that the HOMO is antisymmetric, whilst the LUMO is symmetric. For ethene, an energy of 0.02619028 a.u. and a point group of D2h. Conversely to the cis butene, ethene's HOMO is symmetric and its LUMO is antisymmetric.

| HOMO of butadiene | LUMO of butadiene |

|---|---|

|

|

| HOMO of ethene | LUMO of ethene |

|

|

The energies of the HOMO and LUMO of each reactant is summarised in the following table.

| Molecule | HOMO (a.u.) | LUMO (a.u.) |

|---|---|---|

| Cis buta-1,3-diene | -0.34381 | 0.01707 |

| Ethene | -0.38775 | 0.05283 |

The smallest HOMO-LUMO energy gap is the HOMO of cis buta-1,3-diene and the LUMO of ethene, with an energy of 0.39664 a.u.

Optimisation of the Transition State

To obtain the transition structure, the optimised molecules of cis butadiene and ethene were orientated so that the C-C distance between where the proposed σ bonds would be was about 2.2 Å. The molecules were then symmetrised to a Cs point group. As done when reaching the boat structure transition state, the two desired C-C bonds were frozen via the redundant co-ordinate menu, and the structure optimised. a TS(Berny) optimisation was subsequently run with the C-C bond distances unfrozen. This generated the envelope structure shown below, with an energy of 0.11165487 a.u. and a single imaginary vibration at -956.46 cm-1. The lowest real frequency was found to be 147.57 cm-1. The imaginary vibration shows the concerted bond formation at transition state, whilst the lowest real frequency is a rock of the transition state structure.

| Imaginary Frequency | Lowest Real Frequency |

|---|---|

|

|

To confirm that the molecule obtained is the transition structure, an IRC calculation was run, shown below.

| IRC Pathway | IRC Animation |

|---|---|

|

|

The reaction pathway follows the inverse of the reaction, i.e. products to reactants, which is evident from the energy levels on the graph and the animation. However it can be seen the the IRC reaches a gradient of 0 at both the start and finish, showing that both products and reactants were reached. Therefore it is evident that the correct transition structure was obtained.

The HOMO and LUMO of the transition state are shown below. The HOMO is antisymmetric in the xy plane whereas the LUMO is symmetric in the xy plane.

| HOMO of TS | LUMO of TS |

|---|---|

|

|

The energies of the HOMO and LUMO were found to be -0.32395 a.u. and 0.02318 a.u. respectively. As investigated above in the MO analysis of the reactants, the reaction follows normal electron demand as the HOMO of the dienophile is lower than that of the diene. The reaction is also Woodward-Hoffman allowed, due to the symmetry of the orbitals being preserved over the course of the reaction. This is shown by the symmetric LUMO of the transition state being formed the two symmetric reactant orbitals (i.e. the HOMO of ethene and the LUMO of cis bta-1,3-diene) and the antisymmetric HOMO being formed from the LUMO of ethene and the HOMO of cis buta-1,3-diene.

(How do the bond-forming lengths compare to typical C-C lengths and the VdW radius of carbon? Tam10 (talk) 15:45, 11 January 2016 (UTC))

The Reaction of cyclohexa-1,3-diene with maleic anhydride

If the reactants in a Diels Alder reaction are asymmetric, then regioselectivity arises. To investigate this, the reaction of cyclohexa-1,3-diene with maleic anhydride was simulated. Depending on the orientation of the reactants, two different transition states can be formed, known as the endo and exo transition states.

Initially, molecules of maleic anhydride and cyclohexa-1,3-diene were constructed and optimised. Once again, the guess transition structure was made by setting the two molecules so that the distance between the proposed formed σ bonds in the reaction were 2.2 Å, and the molecule symmitrised to the Cs point group. The two C-C bond distances were frozen via the redundant co-ordinate menu, and the molecule optimised. This resultant structure was then optimised to a TS(Berny) without the frozen co-ordinate restriction.

In order to get either the endo or exo product, one of the reactants was rotated by 180 °.

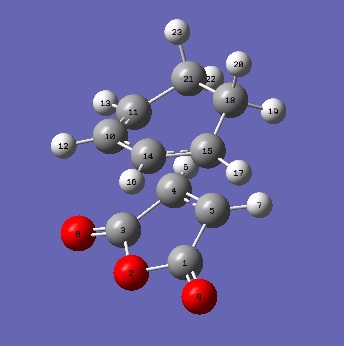

Endo Transition state

The endo transition state was obtained with an energy of -0.05150462 a.u. and a single imaginary frequency at -806.67 cm-1. The imaginary vibration is also shown, indicating a concerted reaction.

| Endo transition state | Energy summary | Imaginary Vibration | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

To analyse the the endo transition state further, an IRC calculation was run. As obtained in the previous exercise, the IRC pathway is in reverse showing products to reactants. It can be seen from the graph that the product plateaus in energy, but the reactants do not. As an IRC calculation with more steps only led to Gaussview producing an error, the final step of the IRC was optimised to see if any major change occured. The energy of the optimised reactants was found to be -0.09472910 a.u. , which is slightly lower than that obtained from the IRC. However, on closer inspection of the resultant molecule structures, this corresponded to the two reactants moving further away from each other with no interaction of the two molecules. Therefore it can be concluded that the transition state shown with the IRC pathway is the only transition state for the reaction. The IRC animation is also illustrated below.

| IRC Graph | Reaction Animation |

|---|---|

|

|

| Optimised reactants | Energy Summary |

|---|---|

|

|

The geometry of the endo structure was also analysed. The two predicted formed σ bonds in the reaction (C5-C15 and C4-C11) are 2.162 Å apart, which is greater than the length of a C-C single bond, but lower than the VDW radius of 2 C atoms. This indicates that a favourable interaction is present in the transition state. Furthermore, the bonds involved in the concerted ring transition state are between the values of a C-C single and double bond (C4-C5 = 1.408 Å, C14-C10 = 1.397 Å, C10-C11 = 1.393 Å). This indicates a bond order between 1 and 2, expected for the transition state.

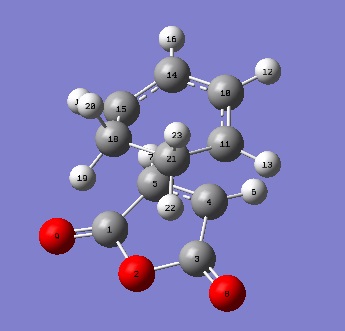

Exo Transition state

The exo transition state was obtained with an energy of -0.05041978 a.u. and a single imaginary frequency at -812.46 cm-1. The imaginary vibration is also shown, as before indicating a concerted reaction.

| Exo transition state | Energy summary | Imaginary Frequency | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

To analyse the the exo transition state further, an IRC calculation was run. Unlike the endo structure IRC, the reaction pathway for the exo structure goes from reactants to products. However as before, the product plateaus in energy, but the reactants do not. Again the IRC calculation with more steps only led to Gaussview producing an error so the initial step of the IRC was optimised to see if any major change occured. The energy of the optimised reactants was found to be -0.09472910 a.u. , which is slightly lower than that obtained from the IRC. However, as before, this corresponded to the two reactants moving further away from each other with no interaction of the two molecules. Therefore it can be concluded that the transition state shown with the IRC pathway is the only transition state for the reaction. The IRC animation is also illustrated below.

| IRC Graph | Reaction Animation |

|---|---|

|

|

| Optimised reactants | Energy Summary |

|---|---|

|

|

Like the endo structure, The geometry of the exo structure was analysed. The two predicted formed σ bonds in the reaction (C5-C15 and C4-C11) are 2.170 Å apart, indicative of the same positive interaction found before. Also, the bonds involved in the concerted ring transition state were found to be between the length of a single and double bond again, expected for the transition state. (C4-C5 = 1.410 Å, C14-C10 = 1.397 Å, C10-C11 = 1.394 Å)

Energy and Orbital Comparison of Exo and Endo Product

The energies of the two transition structures, along with cyclohexa-1,3-diene and maleic anhydride are summarised below. The activation energies can then be calculated.

| Endo Transition State | Exo Transition State | Cyclohexa-1,3-diene | Maleic Anhydride | Sum of Reactant Energies | ΔE Endo | ΔE Exo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -0.05150462 | -0.05041978 | 0.02771128 | -0.12182418 | -0.09411290 | 0.04260828 | 0.04369312 |

When the two activation energies are converted to kJmol-1, this gives the endo TS activation energy as 111.9 and the exo TS activation energy as 114.7. This indicates that the endo product is the favoured kinetic product, as the activation barrier is 2.8 kJmol-1 lower in energy.

The reasoning behind the different transition structure energies can be rationalised by viewing their geometry and MOs, as the relative energies of the two transition states can be viewed as a compromise between strain in the molecule backbone structure and stereoelectronic effects. A comparison of the C-C internuclear distance between a C atom in a carbonyl group on maleic anhydride to the closest C atom on the cyclohexa-1,3-diene (the CH-CH carbons for the endo TS, and the CH2-CH2 carbons for the exo structure). Both distances are lower than double the VDW radius of carbon (1.70 Å)[7], with the internuclear distance being slightly smaller for the endo structure. This indicates strain on both transition state structures, with slightly more strain found in the endo structure.

However the exo structure also has strain between the lower CH2 hydrogens and the oxygens on the C=O groups. The VDW radii of oxygen is 1.52 Å and hydrogen is 1.20 Å[7], and so the internuclear distance found in the exo structure is lower than that of the combined radii. This unfavourable interaction produces further strain on the molecule which is not found on the endo product, and hence contributes to the higher energy of the exo structure.

| Endo TS | Exo TS |

|---|---|

| |

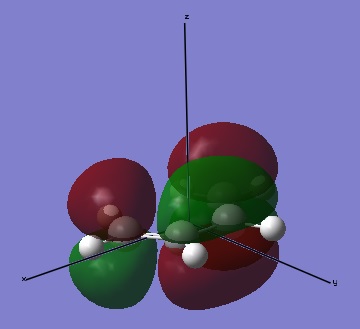

The HOMO and LUMO of both structures are shown in the table below.

| TS | HOMO | LUMO |

|---|---|---|

| Endo Transition State |

|

|

| Exo Transition State |

|

|

By inspection it can be seen that both the HOMO and LUMO of both molecules is antisymmetric. However, the LUMO of both structures has a nodal plane through the forming bonds between the two reactants. This is indicative of an unfavourable interaction which is expected of the higher electronic state. For the HOMO of the endo transition structure, it can be seen that there is a significant stereolectronic effect between the π* orbital of the C=O bonds and the π orbitals of the diene. This is unlike the HOMO of the exo transition state, which has no interaction between the two due to them lying on opposite sides of the structure. This lowers the overall energy of the endo structure.

Conclusion

During the experiment, the Cope Rearrangement reaction was studied, with particular focus on the properties of the transition state. Initially different conformers of the hex a-1,5-diene were analysed to determine the lowest energy conformer. This was found to be the gauche3 structure due to the stereo electronic effect of favourable π bond overlap. Both the chair and the boat conformation were analysed under two different methods, Hartree Fock 3-21G and DFT 6-31G*. It was found that both methods gave the chair structure as the preferred pathway, although when calculating values of activation energy to compare with literature, only the DFT 6-31G* method gave the correct values.

In the second part of the exercise, two Diels Alder reactions of cis buta-1,3-diene with ethene and maleic anhydride with cyclohexa-1,3-diene under the semi empirical AM1 method. For the first reaction an envelope shape was obtained, and proven to be a transition state by measuring the formed C-C bond distances and viewing the molecule HOMO and LUMO. The C-C bond distances were longer than that of a C-C σ bond, but shorter than double the VDW radius of a carbon atom. The HOMO and LUMO matched in symmetry to the HOMO and LUMO of both ethene and cis buta-1,3-diene, indicating an electronically allowed pericyclic reaction. For the reaction of maleic anhydride with cyclohexa-1,3-diene, the asymmetric nature of the molecule led to the reaction having 2 products, the endo and exo product. The optimised transition states for both reaction pathways were obtained, and their activation energies compared. It was found that the endo structure was the kinetically favoured transition state. Although both structures were strained, shown by the internuclear carbon distances, the secondary orbital overlap found in the endo structure after computing the HOMO and LUMO of both transition states led to it having a lower energy.

References

- ↑ "Cope rearrangement revisited", R. Hoffmann, W. D. Stohrer, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1971, 93 (25), pp 6941–6948

- ↑ Imperial College London, Computational Chemistry Wiki [1]

- ↑ M. Y. Amusia, A. Z. Msezane, V. R. Shaginyan, Density Functional Theory versus the Hartree–Fock Method: Comparative Assessment, Physica Scripta. Vol. T68, C133–140, 2003

- ↑ E. G. Lewars, Computational Chemistry, DOI 10.1007/978-90-481-3862-3_2, Springer Science + Business Media B.V. 2011, Ch.2, p16-18, 28-36.

- ↑ K. J. Shea,* G. J. Stoddard, W. P. England, and C. D. Haffner, 2638 J. Am. Chem. Soc.. Vol. 114, No. 7, 1992

- ↑ J. Sauer, Diels-Alder Reaction II: The Reaction Mechanism, Angew. Chem. internat. Edit. VoI. 6 (1967) / No. I

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 A. Bondi, Van der Waals Volumes and Radii., J. Phys. Chem, 1964 68(3), 441-451.