Rep:Mod:JPSO

Synthesis and Computational Experiment - 1C

This page details the steps undertaken to investigate the properties, reactions and energies of various organic molecules.

Conformational analysis using Molecular Mechanics

In this part of the experiment, different conformations of various molecules were modeled to examine their relative energies and stabilities

Hydrogenation of the Cyclopentadiene Dimer

In this section, the endo and exo forms of the cyclopentadiene dimer were modeled and their relative energies calculated using the MMFF94s calculation of the Avogadro program.

The endo and exo forms were drawn and the energy minimised to this level. The resulting values were: 55.37kcal/mol for the exo conformer, and 58.19kcal/mol for the endo form. Thermodynamically, this would predict that the exo state would be the major form, however this is contrary to the observed result, in which the endo product is the only form seen. This can only be due to the reaction proceeding kinetically, and is driven by some secondary orbital overlap effect.

The thermodynamic stability of the exo form compared to the endo form is most likely due to the through space inter-atomic distances between the closest carbon atoms, of which the exo form has a distance of 3.4Å, and the endo form 3.0Å. In the two structures shown, the higher of the two is the endo conformer, and the lower is the exo.

endo |

exo |

The hydrogenated endo forms of these compounds were then subjected to analysis by running an MMFF94s calculation in order to interpret the reaction with respect to kinetic or thermodynamic effects. The values given by this calculation can be seen below:

| Value | Conformer 3 | Conformer 4 |

|---|---|---|

| Stretching Energy/kcal.mol-1 | 3.30778 | 2.81592 |

| Bending Energy/kcal.mol-1 | 28.95052 | 23.07703 |

| Torsion Energy/kcal.mol-1 | 0.06492 | -0.35025 |

| Van der Waals Energy/kcal.mol-1 | 13.27863 | 10.58073 |

| Electrostatic Energy/kcal.mol-1 | 5.12098 | 5.14736 |

| Total Energy/kcal.mol-1 | 50.72283 | 41.27080 |

From the total energies it is clear that conformer 4 is the more stable of the hydrogenated dimer. This would imply that this geometry is the most thermodynamically stable form. Literature suggests that this is also the kinetic product of the mono-hydrogenated product[1]. If left for a longer period of time, the tetra-hydrogenated product results, however conformation 4 forms first.

The calculated values in this section show that the dimerisation of cyclopentadiene is kinetically controlled as the thermodynamically most unstable product is favoured, however the hydrogenation of this endo form of dicyclopentadiene proceeds in a manner by which it seems as though the resulting product is both the thermodynamic and kinetic product. This is manifested in the above data, where it can be seen that conformer 4 has lower energies throughout. This could be due to the lower bending energy in 4 than in 3, therefore producing a less sterically hindered, and therefore more stable, product. These lower energies could also lead to a lower kinetic barrier as the two molecules can combine more easily.

Atropisomerism in an Intermediate Related to the Synthesis of Taxol

In this section, a key intermediate in the synthesis of the drug taxol (used to treat ovarian cancer) was investigated to find the most stable form and to understand why this molecule reacts so slowly. The two isomers investigated were molecules 9 and 10. Again, an MMFF94s calculation was used in Avogadro to calculate the relative energies of these two intermediates. In carrying out these calculations, it was found that there were two different 'boat' conformations for the cyclohexane part of the intermediate. These conformers are labeled as a and b in the table below, where the energies for the two intermediates can be seen:

| Value | Intermediate 9a | Intermediate 9b | Intermediate 10a | Intermediate 10b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stretching Energy/kcal.mol-1 | 7.65783 | 7.81145 | 7.59479 | 8.08713 |

| Bending Energy/kcal.mol-1 | 29.144 | 30.16978 | 19.50716 | 23.93167 |

| Torsion Energy/kcal.mol-1 | 0.49692 | 4.37249 | 0.23180 | 5.58194 |

| Van der Waals Energy/kcal.mol-1 | 33.12548 | 35.41179 | 33.27081 | 35.33326 |

| Electrostatic Energy/kcal.mol-1 | 0.28220 | 0.28277 | -0.05426 | 0.36636 |

| Total Energy/kcal.mol-1 | 70.70642 | 78.04828 | 60.55030 | 73.30037 |

For intermediate 9, one of the conformations appeared to be a twist-boat, clearly giving the higher of the two energies. This data shows that the lowest overall energy is provided by intermediate 10a, and so this is therefore the form that the compound will isomerise to if left for a period of time. This stability of 10a (≈10kcal/mol less than 9a) is likely to be due to there being unfavourable bond angle in 9. In 9a, the C-C=O angle was measured to be 117.4°, whereas in 10a it was 120.4°. As this carbon is sp2 hybridised, the most favourable bond angle will be the one that is closer to the optimal value of 120°, which is clearly intermediate 10.

Studies have also shown that this alkene reacts unusually slowly due to a phenomenon known as hyperstability[2], in which alkenes are highly stabilised due to their position at a bridgehead. This positioning means that they are less strained than their parent hydrocarbon, and therefore show decreased reactivity at the double bond. This stability has been shown to be due to the "cage" structure of the molecule, and its ability to effectively guard the double bond and prevent it reacting. These hydrogenated molecules - Molecule 9 and Molecule 10 were modeled using 'ChemBio3D' and the bond angles where the C=C bond was previously were measured to be 119.8 °and 120° respectively - clearly unfavourable bond angles for an sp3 carbon atom. This torsional strain is another reason by which these types of alkenes are hyperstable.

Spectroscopic Simulation using Quantum Mechanics

In this section, spectroscopic simulations of molecules were run, in order to correlate the computational data with that attained experimentally.

Spectroscopy of an Intermediate Related to the Synthesis of Taxol

Molecules 11 and 12 were drawn in Avogadro and optimised as before to the MMFF94s level. The geometry of the cyclohexane part of the molecules was adjusted to be in a chair conformation, so that the energy would go to a minimum. The energies of these molecules were calculated to be 110.44939kcal/mol and 102.40556kcal/mol respectively. The lowest energy of these two molecules (12) was the used to calculate the NMR spectrum. The molecule used to carry out this calculation can be found here.

This was done by running a Geometry Optimisation from the Gaussian extension of Avogadro, selecting a B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) level and adding the keywords: SCRF(CPCM, solvent=chloroform), FREQ, NMR and EmpiricalDispersion=GD3. This generated a .com file which was then submitted to the HPC.

Once completed, this file was downloaded to GaussView and the 13C NMR, 1H NMR, and IR spectra observed. The data attained from these computationally generated spectra along with the literature values can be seen below:

Computational and Literature NMR Shifts

| Computational 1H δ (ppm) | Literature 1H δ (ppm)[3] | Computational 13C δ (ppm) | Literature 13C δ (ppm)[3] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.42 (1H) | 1.03 (s, 3H) | 22.26 | 19.83 |

| 0.83 (1H) | 1.07 (s, 3H) | 23.11 | 21.39 |

| 1.06 (2H) | 1.10 (s, 3H) | 25.26 | 22.21 |

| 1.26 (1H) | 1.20-1.50 (m, 3H) | 25.70 | 25.35 |

| 1.42 (1H) | 1.58 (t, 1H) | 27.69 | 25.56 |

| 1.50 (2H) | 1.70-2.20 (m, 6H) | 30.42 | 30.00 |

| 1.60 (3H) | 2.35-2.70 (m, 4H) | 32.66 | 30.84 |

| 1.69 (1H) | 2.70-3.00 (m, 6H) | 35.31 | 35.47 |

| 1.81 (2H) | 5.21 (m, 1H) | 39.15 | 36.78 |

| 1.96 (4H) | - | 39.95 | 38.73 |

| 2.08 (1H) | - | 41.72 | 40.82 |

| 2.28 (1H) | - | 46.30 | 43.28 |

| 2.52 (2H) | - | 49.84 | 45.53 |

| 2.84 (2H) | - | 53.85 | 50.94 |

| 2.97 (1H) | - | 58.49 | 51.30 |

| 3.03 (1H) | - | 62.08 | 60.53 |

| 3.15 (1H) | - | 91.54 | 74.61 |

| 3.22 (1H) | - | 123.92 | 120.90 |

| 3.30 (1H) | - | 151.46 | 148.72 |

| 5.33 (1H) | - | 209.75 | 211.49 |

From this data, it is clear that the computationally generated values are very similar to that found in the literature, particularly for the 13C NMR data. There are also fewer peaks in the literature for the 1H NMR data than were generated computationally. This is most likely due to protons actually being in very similar environments, meaning that they would be seen experimentally as just one peak, but computationally shown as a number of peaks. The ranges of δ values in the literature (e.g 2.70-3.00) which correspond to a multiplet imply that there were multiple separate signals overlapping, that merged into one signal.

It is likely that different conformations (chair and boat) of molecule 18 would have produced slightly different chemical shifts, but it is unlikely that they would have been drastically different from the most stable chair conformation used in this calculation.

The (relatively slight) differences between chemical shifts for both sets of NMR data is potentially due to the difference in solvent used. In the computational calculation, CDCl3 was used, however in the literature, C6D6 was used. The largest variation is in the 13C NMR data at 91.54ppm (computational), where the corresponding literature value is 74.61ppm. This peak is due to the quaternary carbon at the head of the cyclopentyl ring, that is bonded to two sulphur atoms, and is likely to be different due to spin-orbit coupling errors, that originate from this carbon being bonded to two much heavier atoms. This is corrected simply by taking off a number of ppm from that of the computationally generated shift.

A final reason for slight differences between the computational and experimental values could be again due to conformers. In the computational spectrum, it was limited to the cyclohexane part of the molecule being solely in one of the 4 possible conformations. The experimental moleule would not have been limited to this, and so the spectrum would have been made up of average shifts from the relative contributions of each conformation.

The energies of these two conformations (11 and 12) were also viewed from the .log file generated. A table of these values can be seen below:

Thermochemical Data for Molecules 11 and 12

| Quantity | Molecule 11 | Molecule 12 |

|---|---|---|

| Sum of electronic and zero-point Energies/kcal.mol1 | -1036270 | -1036278 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal Energies/kcal.mol1 | -1036256 | -1036265 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies/kcal.mol1 | -1036255 | -1036264 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies/kcal.mol1 | -1036300 | -1036308 |

The final of these quantities corresponds to the Gibbs Free Energy of the molecule and it is clear that molecule 12 is slightly lower in energy.

Analysis of the Properties of the Synthesised Alkene Epoxides

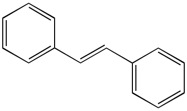

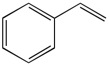

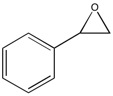

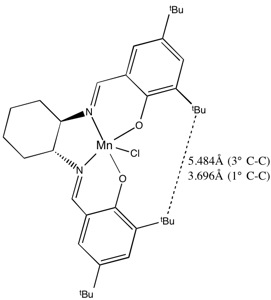

In this section, asymmetric epoxidation reactions involving Styrene and trans-Stillbene to produce the epoxides shown were investigated using similar analytical techniques to those already used. This analysis involves the 'use' of two different asymmetric eopxidation catalysts - the Shi and Jacobsen - which produce two different chiral alkene epoxides of unknown absolute configurations. The Shi catalyst reacts with a trans- alkene to produce an epoxide of the same geometry, whereas the Jacobsen catalyst reacts with cis- alkenes. This section of the study involves modeling the catalysts and products, in order to compute NMR spectra, and find the absolute configurations of the epoxides formed.

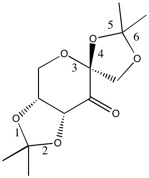

Crystal Structure of Shi and Jacobsen Catalysts

The Cambridge crystal structure database was searched to find the various bond lengths for the Shi catalyst and Jacobsen catalyst.

In the Shi catalyst, there are a number of stabilising interactions due to the 2 (O-C-O) sections (anomeric centres). On initially viewing the molecule, it may appear that there are 3 of these interactions, 2 on each of the cyclopentyl rings, and one on the cyclohexyl ring. However, due to the steric arrangement of the molecule, it is impossible for the centre on the cyclohexyl ring to be stabilised by interaction between the oxygen lone pair and the C-O antibonding orbital (σ*). These interactions do occur in the cyclopentyl rings as there is sufficient overlap between the two orbitals. For a good overlap to occur, the oxygen lone pair and the C-O σ* orbitals must be syn-periplanar. In the A summary of these bonds can be found below:

Summary of bond Lengths in Shi Catalyst

| Bond | Length(Å) |

|---|---|

| 1 | 1.409 |

| 2 | 1.439 |

| 3 | 1.403 |

| 4 | 1.403 |

| 5 | 1.441 |

| 6 | 1.413 |

The bond lengths show that there are two bonds (2 and 5) that are clearly affected by this donation into the (low energy) C-O σ* orbital, however their adjacent bonds (1 and 6) do not appear to have been affected (given that the normal C-O bond length is 1.43Å). However, these bonds lengths are still longer than those unaffected by this anomeric effect. This may be due to the cyclopentyl rings not being exactly planar, and these interactions being slightly weaker than those for bonds 2 and 5. It is clear that there is no such antibonding effect in the cyclohexyl ring (3 and 4) as the bonds are of equal length and are shorter than normal C-O bonds.

The distance between the closest two tert-butyl groups in the Jacobsen catalyst was then measured. As can be seen from the diagram, the closest approach of the two primary carbons is 3.696Å - only slightly longer than double the Van der Waal's radius of carbon (3.4Å). This means that this side of the catalyst is very sterically hindered, especially as other parts of the molecule prohibit rotation, leading to the preference of the incoming alkene to approach from over the cyclohexane ring. Finally, the distance between two of the hydrogens of the tert-butyl group was measured to be 2.421Å - potentially Van der Waal's attractive - and therefore contributes to the preference of these groups to hinder the attach of the alkene. The maximum attraction distance of these two hydrogens is 2.4Å, meaning that rotation of the two methyl groups could lead these atoms to become closer, and therefore more attractive.

Calculated NMR of the Product Epoxides

The epoxides that were investigated were (R)-phenylethylene oxide (from styrene) and (R,R)-trans-stillbene oxide (from trans-stillbene). Clearly, two isomers of these epoxides can be formed (S and trans respectively), however each were found to have identical NMR spectra The NMR spectra were calculated using a similar method to before, and the data can be found below:

Summary of NMR Data for (R)-phenylethylene oxide

| Comptuational 1H (ppm) | Literature 1H (ppm)[4] | Comptuational 13C (ppm) | Literature 13C (ppm)[4] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.53 (1H) | 2.81 (1H) | 53.48 | 51.2 |

| 3.12 (1H) | 3.13 (1H) | 54.06 | 52.4 |

| 3.66 (1H) | 3.84 (1H) | 118.27 | 125.5 |

| 7.29 (1H) | 7.27-7.34 (5H) | 122.25 | 128.1 |

| 7.49 (4H) | - | 123.41 | 128.5 |

| - | - | 124.13 | 137.6 |

| - | - | 135.14 | - |

From the data it is clear that the computationally generated 1H and 13C NMR spectra for (R)-phenylethylene oxide are very similar to that in the literature, except in the fact that for the carbon NMR, the computationally generated spectrum shows 7 environments, whereas the experimental only shows 6. This could be due to the computationally generated spectrum putting two of the benzene ring carbons into different chemical environments, when in actual fact they are chemically equivalent. This correlation clearly leads to the assumption that this epoxide has been modeled correctly.

Below is the same data, but for 1,2-diphenylethylene epoxide:

Summary of NMR data for (R,R)-trans-stillbene oxide

| Comptuational 1H (ppm) | Literature 1H (ppm)[5] | Comptuational 13C (ppm) | Literature 13C (ppm)[6] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4.30 (2H) | 4.36 (2H) | 62.02 | 59.88 |

| 7.25 (2H) | 7.18 (10H) | 122.11 | 127.0 |

| 7.33 (4H) | - | 122.32 | 127.6 |

| 7.40 (2H) | - | 122.62 | 127.9 |

| 7.50 (2H) | - | 131.28 | 134.5 |

Once again, there is good correlation between the computationally generated 1H and 13C spectra and the experimental data. In the 13C NMR, the values are all slightly different, however the magnitude of the differences between the more deshielded carbons is similar in both computational and literature spectra. Again, this shows that the computationally generated molecule is similar to the actual molecule.

IR data for the styrene epoxide and stillbene epoxide were also generated.

All the NMR spectra, both computational and literature, were run using CDCl3 as a solvent.

Assigning the Absolute Configurations of the Epoxide Products

In this section, the configurations of the epoxides synthesised from styrene and trans-stillbene were analysed. Due to the nature of the two catalysts, two isomers of each product can be made(R or S and [R,R] or [S,S] respectively), each with a different value for the optical rotation. The two values will, however, simply be of the opposite sign, i.e if the rotation for one was +20°, the opposite isomer would be -20°. Therefore, only one of the two isomers was calculated for each product epoxide.

This calculation was carried out by submitting the calculation (based on the .log file from the NMR) to the HPC. The values calculated using this method could then be compared to literature values:

Comparison of Computational and Literature Optical Rotations

| Styrene Epoxide | Stillbene Epoxide | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Value (°) | Literature Value (°) | Computational Value (°) | Literature Value (°) |

| -31 | -24[7] (R-stereoisomer) | 294 | 319.8[8] ([R,R]-Diastereoisomer) |

From the table, it can be seen that the literature and computational values for the two epoxides are similar, however a number of drastically different values were found in reaxys for this particular enantiomer of styrene, varying from -40° to +20°. Therefore these similarities should be taken very carefully. It can be assumed that the opposite enantiomer of each of the two epoxides would have an equal but opposite optical rotation. These values indicate, however, that the [R] stereoisomer of the styrene epoxide was made, along with the [R,R] stereoisomer of the trans-stillbene epoxide.

Using the Calculated Transition States to determine the Favoured Enantiomer

In this section, a number of different transition state arrangements of the reaction were analysed for Styrene (Shi catalyst) and cis-β-methyl styrene (Jacobsen catalyst).

Shi Catalyst

The thermochemical data for the Shi catalysed transition state was viewed to determine which of the transition state arrangements - and therefore which isomer (R or S) - would predominate. Tables of this data can be found below, in which the numbers 1 to 4 are simply the 4 transition states.

Summary of Free Energies for Styrene - Shi Transition State

| Transition State | Free Energy of R Transition State/kJ.mol-1 | Free Energy of S Transition State/kJ.mol-1 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | -3422945.221 | -3422953.426 |

| 2 | -3422944.001 | -3422928.090 |

| 3 | -3422961.263 | -3422937.266 |

| 4 | -3422964.495 | -3422965.700 |

From this data, it is clear that both transition state 4 are the most stable, with the S form being slightly more stable (by 0.17 kJ/mol). The difference in free energy between the R and S forms (denoted ΔG here) allowed the rate constant for the rate constant, K, to be calculated using the equation: G = -RTlnK, taking T to be 298.15K. This data is found in the table below:

Calculated Free Energy and Rate Constant for R to S ratio

| ΔG of S:R/kJ.mol-1 | Equilibrium Constant for S:R |

|---|---|

| -1.205 | 1.626 |

This value of the equilibrium constant suggests that for each molecule of configuration R formed, 1.63 molecules of configuration S form. Put more simply, 63% of the mixture will be S, and 37% will be R. The larger proportion of S to R could be due to enhanced interactions (hydrogen bonding, Van der Waal's forces, etc) between the catalyst and the alkene, and furthermore, the arrangement of this transition state appears less sterically hindered that that forming the R product. These differences must be very slight, as the relative proportions is not greatly changed. The arrangement of these transition states can be found here for R and here for S.

Jacobsen Catalyst

The same procedure was carried out, but using the data for the use of the Jacobsen catalyst to epoxidise cis-β-methyl styrene. For this alkene, it is possible for a different two enantiomers to form - [S,R] and [R,S]. The energies of these can be found below:

Summary of Free Energies for cis-β-methyl styrene - Jacobsen Transition State

| Transition State | Free Energy of [S,R] Transition State/kJ.mol-1 | Free Energy of [R,S] Transition State/kJ.mol-1 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | -8882748.649 | -8882726.335 |

| 2 | -8882732.589 | -8882724.261 |

From the table, it can be seen that 1 for both the [S,R] and [R,S] isomers is the most stable. These were therefore used as before to give the results shown below:

Calculated Free Energy and Rate Constant for S,R to R,S ratio

| ΔG of [S,R]:[R,S]/kJ.mol-1 | Equilibrium Constant for [S,R]:[R,S] |

|---|---|

| -22.314 | 8118.6 |

This shows that the [S,R] enantiomer is highly favoured over the [R,S], with an enantiomeric excess of >99%. This may be due to sterics or orbital overlaps in the transition state, however it is unclear from simply looking at these transition states why one is so strongly favoured over the other. The [R,S] diastereoisomer can be found here, and the [S,R] diastereoisomer can be found here.

Investigating the non-covalent interactions (NCIs) in the active-site of the reaction transition state

In this section, the interactions within the transition states were analysed by examining the electrostatic attractions in these states, also known as non-covalent interactions. The transition state examined was that created by the reaction of [S,R]-dihydronaphthalene with the Shi catalyst. 4 of these transition states were viewed in order to find which had the lowest free energy value, and so was the transition state by which the reaction proceeded.

From the picture, it can be seen that there are areas that are very attractive - shown by blue/green, areas that are less attractive - shown by yellow, and areas that are repulsive - shown by red. In between the two molecules, there are regions of green, showing attractive interactions (likely to be hydrogen bonds between the H's (on dihydronapthalene) and O's (on Shi catalyst)) There is also a very unusual region at the point at which the epoxide is forming, where it appears that there are both attractive and repulsive forces operating. This could be due to both electons repelling each other, but the two regions also being attracted to one another due to interatomic forces attempting to form the bond.

Investigating the Electronic topology (QTAIM) in the active-site of the reaction transition state

In this section, the objective was to analyse the electron density in the covalent regions of the same transition state as used above, along with the weaker interactions found in the NCI investigation. The picture of these interactions can be seen below:

From this picture, a number of different interesting points can be seen, denoted by yellow dots. At these points, the derivative of the electron density is zero, and therefore the actual electron density is at a maximum. For the oxygen atoms in the catalyst, this dot is closer to the oxygen, clearly closer to this atom due to the larger electronegativity of the oxygen atom. This can also be seen for the hydrogen atoms on the napthalene ring. Also, the dotted lines in the picture denote weaker interations, in this case hydrogen bonds between oxygen and hydrogen, and it can be seen that the maximum electron density of this interaction is approximately in the middle of these two atoms.

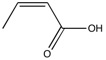

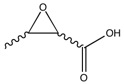

New Candidates for Investigation

In this final section, Reaxys was searched using the criteria that the optical rotation of the materials searched for (epoxides) has that which was <+500° or >-500°. A potential candidate found was Crotonic acid and its corresponding eopoxide, 2,3-epoxybutyric acid. This was chosen as the alkene could be asymmetrically epoxidised, therefore producing diastereoisomers. These isomers were found to have relatively large optical rotations - ≈±80°[9] - and therefore the results obtained experimentally and computationally could be analysed well. Furthermore, there is only one double bond, so it would be expected that this would be produced in a relatively high yield.

References

- ↑ Kinetics of Dicyclopentadiene Hydrogenation using Pd/C Catalyst, D. Skála and J. Hanika, Petroleum and Coal, 2003, 45, pp. 105-108

- ↑ W. F. Maier, P. Von Rague Schleyer, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1981, 103, 1891. DOI:10.1021/ja00398a003

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Paquette, Leo A.; Pegg, Neil A.; Toops, Dana; Maynard, George D.; Rogers, Robin D. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 1990 , 112, # 1, 277 - 283. DOI:10.1021/ja00157a043

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Chen, Xin-Zhi; Ji, Li; Qian, Chao; Wang, Ya-Na; Qian, Chao Synthetic Communications, 2013 , 43, # 16 pp. 2256 - 2264. DOI:10.1080/00397911.2012.699578

- ↑ Berardi, Serena; Bonchio, Marcella; Carraro, Mauro; Conte, Valeria; Sartorel, Andrea; Scorrano, Gianfranco Journal of Organic Chemistry, 2007 , 72, # 23 pp. 8954 - 8957. DOI:10.1021/jo7016923

- ↑ Mai, Enzo; Schneider, Christoph Chemistry--A European Journal, 2007 , 13, # 9 pp. 2729 - 2741. DOI:10.1002/chem.200601307

- ↑ David C. Forbes, Sampada V. Bettigeri, Samit A. Patrawala, Susanna C. Pischek, Michael C. Standen, S-Methylidene agents: preparation of chiral non-racemic heterocycles, Tetrahedron, 65, # 1, 2009, pp. 70-76, ISSN 0040-4020, DOI:10.1016/j.tet.2008.10.019

- ↑ Wang, Bin; Wu, Xin-Yan; Wong, O. Andrea; Nettles, Brian; Zhao, Mei-Xin; Chen, Dajun; Shi, Yian Journal of Organic Chemistry, 2009, 74, # 10 pp. 3986 - 3989 DOI:10.1021/jo900330n

- ↑ Akita, Hiroyuki; Kawaguchi, Tomoko; Enoki, Yuko; Oishi, Takeshi Chemical and Pharmaceutical Bulletin, 1990 , 38, # 2 pp. 323 - 328