Rep:Mod:JB713TS

Transition states and reactivity

This experiment involved the use of Gaussview to analyse the energy and geometries of various molecules and transitions states using various methods and basis sets. Through this the knowledge of the methods were built up to analyse a Diels Alder reaction between 1,5-Cyclohexadiene and Maleic Anhydride.

All of the relevant .Log files can be found in the appendix.

Tutorial exercises

Optimising reactants and products

The first task was to create an anti conformation of 1,5-hexadiene. This was then optimised using the Hartree Fock method with a 3-21G basis set. The hartree fock method which utilises a single slater determinant to evaluate the wave function of a system[1]. It is a simple and fast basis set ideal for simple systems and quick calculations that wont necessarily yield results that are indicative of experimental but provide a vague idea of the values and geometry expected[2].

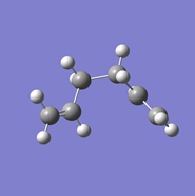

A Gauche conformation for 1,5 hexadiene was created and optimised under Hartree-Fock method with 3-21G basis set and yielded the molecule shown in fig 3. The summary for this calculation can be seen in fig 4. As seen in fig 4. the energy of this conformation is -231.68771617 hartrees with a point group of C2. As expected this energy is higher than the anti conformation as the gauche conformation leads to energetically disfavourable gauche interactions which increase the energy. Note that this energy value is accurate to 5 decimal places with respect to the value given in the script.

When considering which conformer would be the lowest I ended up creating anti2, as it seemed to have the least steric hindrance in regards to the two bulky alkene groups being as far apart as possible ,and as such the analysis of this conformation will be shown later in the wiki.

In actuality the lowest conformer is gauche3, this can be seen in fig 5. with the summary in fig 6. once again the energy = -231.69266120 hartrees is accurate to 5 decimal places with respect to the script and has a point group of C2. Gauche3 is the lowest energy conformer because of favourable orbital overlap.

Anti2 was then created an optimised under the same conditions, HF/3-21G, this can be seen in fig 7. with the summary in fig 8. This yielded an energy value of -231.69253530 hartrees and as such is slightly higher than gauche3 thus it seems the favourable overlap of orbitals has a greater stabilising effect than the sterics involved. However if one was to increase the bulk of the groups on the terminal carbons it is plausible that the anti2 conformation would be the most energetically favourable as the steric alleviation would become a greater stabilising contributor than a potential orbital interaction.

Nf710 (talk) 10:32, 18 January 2016 (UTC) Well balanced argument for orbital stabilisation however you could have shown this by using the orbitals in the .chk file.

Reoptimising via the B3LYP/6-31G* method

The anti2 molecule was then reoptimised using the B3LYP/6-31G* method, this unlike Hartree Fock utilises density functions of the electrons to determine things like repulsion when accounting for the energy and as such generally creates structure closer to those found experimentally. The 6-31G* optimisation of the anti2 conformation can be seen in fig 9, it yielded an energy value of -234.61171168 hartrees The table below displays a comparison of each the conformations as well as the various energies related to them at the 6-31G* basis set. Comparison between the basis sets is pointless hence only 6-31G* is shown as it is more pertinent in regards to experimental values.

Nf710 (talk) 10:36, 18 January 2016 (UTC) Correct understanding of comparison between basis sets. DFT account for electron correlation. No geom comparison. No freq calculation

Optimising the chair and boat transition structures

Please note that for parts c onwards in the script Log files were used to complete the tutorials due to a known bug regarding opening .chk files The second part of the tutorial involved simulating the Cope rearrangement, a sigmatropic rearrangement of a molecule, in this case 1,5 Hexadiene. Different methods such as the redundant coordinate method and utilising QST2 were carried out to create simulate both a boat and chair transition state.

An allyl fragment, fig 11., was created an optimised under HF/3-21G conditions as can be seen in the summary,fig 12., the energy value is -115.82304010 hartrees

This allyl fragment was then duplicated and adjusted to resemble the chair transition state seen in fig 13.. The Intermolecular distance chosen was 2.2 Å.

Note that this was optimised to a transition state via the TSBerny method calculating the Force constants once. This resulted in an inter-fragment distance of 2.02045 Å.

As can be seen in fig 15, the expected imaginary frequency of approximately -818 cm-1, in this case -817.89 cm-1 is observed. An animation of this can be seen below in the JSmol, this is indicative of the Cope rearrangement as shown by the terminal carbons 'forming and breaking bonds'. The imaginary frequency indicates the breaking and formation of bonds at the TS, only one imaginary frequency should be observed and as such it can be used as a diagnostic tool to determine whether or not one has reached a TS.

The terminal carbons of each allyl fragment were then frozen via the redundant coordinate editor. By Freezing the terminal carbons it makes it so that all other carbons at that point get optimised so that when they get unfrozen all that needs to optimised is the inter-fragment bond distance between the previously frozen carbons. The result can be seen in fig 16. The resulting output was then changed so that the previously frozen bonds were changed to compute the derivative. This can be seen in fig 17. The geometry changed due to this with the bond lengths altering to 2.01413 Å from the previously frozen 2.2 Å.

Computing the boat transition structure was done differently to the previous method. Initially the anti2 product was used and copied into a molecule group as seen in fig 18., the labels were changed to correspond to one another and a QST2 transition state calculation was run, this failed as it didnt rotate the molecule about the central two carbons to form the boat structure as such the molecule was adapted to closer resemble the boat transition state by changing the central dihedral angle to 0 and the inner carbons' angle to 100 the QST2 was then run again and succeeded resulting in the JSmol below, this can also be seen in fig 20. The failed attempt can be seen in fig 19.

The JSmol below shows the imaginary frequency of the Boat transition state. The energy value of the boat was found to be -231.60280247 hartrees which is accurate to 6 decimal places with respect to the script. The inter-fragment bonds optimised to a value of 2.13966 Å

An IRC of the chair transition state was run with 100 steps, the path for which can be seen in fig 21., note this was carried out in the forward directions only and shows the decline from the transition state maxima, i.e. the potential surface's equilibrium point. This IRC ran for 44 steps before reaching completion.

This table displays the various energy values for the 3-21G optimisations, as mentioned previously the HF/3-21G values are very close to values given in the script generally accurate to 6 decimal places however there is some deviation in the 6-31G* results which are generally accurate to 4 or 5 decimal places relative to the script.

| HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic energy | Sum of electronic and zero-point energies | Sum of electronic and thermal energies | Electronic energy | Sum of electronic and zero-point energies | Sum of electronic and thermal energies | |

| at 0 K | at 298.15 K | at 0 K | at 298.15 K | |||

| Chair TS | -231.619322 | -231.466700 | -231.461340 | -234.556931 | -234.414908 | -234.408980 |

| Boat TS | -231.602802 | -231.450928 | -231.445299 | -234.543078 | -234.402357 | -234.396012 |

| Reactant (anti2) | -231.692535 | -231.539539 | -231.532566 | -234.611711 | -234.469214 | -234.461866 |

The table below shows a comparison of the ΔE values for HF/3-21G and B3LYP/6-31G* for the boat, chair and anti2 conformations. The values are in kCal/mol

| HF/3-21G | HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G* | B3LYP/6-31G* | Expt. | |

| at 0 K | at 298.15 K | at 0 K | at 298.15 K | at 0 K | |

| ΔE (Chair) | 45.70 | 44.69 | 34.08 | 33.19 | 33.5 ± 0.5 |

| ΔE (Boat) | 55.60 | 54.76 | 41.95 | 41.32 | 44.7 ± 2.0 |

Note that the ΔE values are near identical to those in the script. This is as expected with the 3-21G values as they are also nearly identical to the values in the script, however for B3LYP/6-31G* the values are just different enough that it could've plausibly caused a rather large error as even though we're dealing with differences in the ten/hundred thousandths converting by a reasonably large factor can exacerbate these errors however despite this it seems that the difference in the value for the ones carried out here and the difference in values given by the script are equal suggesting successful calculation of the transition states as the activation energy for the respective transitions is equivalent. Further evidence is of course the single imaginary frequencies shown above for the transition states which as mentioned previously suggest a successful optimisation to a transition.

The values for 3-21G are well outside of the standard error of the experimental data as is to be expected as 3-21G is a very simple basis set that is merely a rough approximation of the transition state, the values calculated via 6-31G* are also outside but are within 2 standard deviations of the value and as such are much closer to the ideal experimental value, confirming that as expected 6-31G* produces much more accurate results.

Nf710 (talk) 10:48, 18 January 2016 (UTC) For some reason I cant edit on your wiki. In the relavent points. You should have said what your imaginary frequency was for your boat. I can go into the log file so I will let you off. Your energies are correct for the final part and therefore so are your structures. You havent come to the conclusion that the lower basis sets are good for approximating geometry but bad for energies. You have missed out a few things but you have shown a fairly good understanding of the theory

The Diels Alder Cycloaddition

For all of these following calculations the method used was the semi-empirical AM1. This is a much faster method than those used previously as it is based on Hartree Fock but utilises multiple approximations in order to speed up the process particularly in regards to large molecules/systems in which this is an ideal substitute for the 3-21G basis set.

Initially a Cis Butadiene molecule was created and optimised. The resulting output can be seen in fig 22.

The HOMO and LUMO of Cis Butadiene can be seen in the table below. The HOMO is anti-symmetrical with respect to the plane whereas the LUMO is symmetrical, via inspection of the amount of nodes. The energy of the Cis Butadiene was found to be 0.04879718 hartrees

| Butadiene HOMO | Butadiene LUMO |

|---|---|

|

|

Then a molecule of Ethylene was optimised as seen in fig 23, the energy was found to be 0.02619027 hartrees, the LUMO is anti-symmetrical with respect to the plane and the HOMO is symmetrical and can be seen in the table below.

| Ethylene HOMO | Ethylene LUMO |

|---|---|

|

|

These two molecules were then taken and placed 2.2 Å away from one another to resemble the desired transition state and optimised to a TS via the TSBerny method, this yielded an energy value of 0.11165469 hartrees

The imaginary vibration of the TS at -955.73 cm-1 can be seen below. In addition to this the lowest positive frequency is shown, clearly the lowest positive has no impact in the formation of the transition state and the making/breaking of bonds as it is merely the -CH2 fragments rotating in a single plane whereas the imaginary frequency shows the molecules bending towards and away from one another, i.e. forming and breaking the bonds.

| Imaginary Frequency of the transition state | Lowest positive frequency of the transition state | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The bonds length was found to be 2.11968 Å, the average value for a single C-C bond is 1.54 Å and the value for a C=C double bond is 1.34 Å[3]. The VDW radius of a single Carbon atom is 1.7 Å[4] and as such due to the intermolecular bond length of the transition state is only 0.4 Å larger than the Van der Waals radius one can surmise that the conformation is favourable for the molecule as otherwise one would expect repulsive forces between the two carbons to extend the bond length past the combined radii or potentially not even form the bond at all. However with the bond being significantly longer than the regular C-C bonds it could suggest that the bond itself is weaker.

(In fact, while in a TS, these are not yet bonds. It's best to call it the bond-forming length or by their labels, such as C1-C8 Tam10 (talk) 17:21, 10 January 2016 (UTC))

The HOMO for the transition state can be seen below in fig 26, from this we can see that the HOMO is symmetric with respect to the plane.

The MO seems to consist of the HOMO of the butadiene and the LUMO of the ethylene via inspection of the way the phases combine. This reaction is allowed due to how small the HOMO-LUMO gap is. This allows for the concerted formation/breaking of bonds between the diene and the dienophile. In addition it is also due to the matching symmetry of the Molecular orbitals.

(The symmetry is perhaps more important in deciding whether the reaction is allowed Tam10 (talk) 17:21, 10 January 2016 (UTC))

(How does the TS HOMO compare to the TS LUMO? Tam10 (talk) 17:21, 10 January 2016 (UTC))

Diels Alder Cycloaddition of Maleic anhydride and 1,3-Cyclohexadiene: Endo vs Exo

Please note that when taking screenshots of the MOs for the 1,3-Cyclohexadiene the incorrect file was screenshotted in which there are only 6 hydrogens and not the 8 that should be there and as such the MOs are slightly incorrect. The correct log file was used for the JSMol but when I noticed this error it was too late to rectify this due to an inability to access a Gaussview enabled computer in time. The other MO's are from the correct files and the Exo and Endo products were created with the correct inputs. One would generally expect Orbitals focusing on the alkene carbons for the MOs which can be 'reverse engineered' by comparing the MOs of the Exo and ENdo products with those of the Maleic anhydride and approximating the shape of orbitals required to make the exo/endo products

(Understood. Had you more time it would have been good to see comparisons of the activation and product energies as well Tam10 (talk) 17:21, 10 January 2016 (UTC))

For actually creating the Diels Alder product a molecule of Maleic anhydride was optimised, as well as a molecule of 1,3-Cyclohexadiene. The MOs can be seen in the table below.

| 1,3-Cyclohexadiene | Maleic Anhydride | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,3-Cyclohexadiene HOMO | 1,3-Cyclohexadiene LUMO | Maleic Anhydride HOMO | Maleic Anhydride LUMO |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

These were placed in the respective approximate conformations of endo and exo and run via QST2 to create the transition states. Intuition lead to the initial test conformation to produce these transition structures to be set at 2.2 Å in addition the two pairs of carbons that were the intended targets for bonding between the maleic anhydride and the 1,3-cyclohexadiene were at approximately 45° angles to one another, this ultimately failed. In order to remedy this the two molecules were brought closer together resulting in an intermolecular distance of 1.65 Å and the angle was reduced to 0°. This was found via a few failed iterations in creating the products by simply changing the intermolecular distance, it wasn't until the orientation of the molecules was corrected that the correct products were formed. Unfortunately as time was a factor it was impossible to test if this was exclusively an effect due to the orientation or a combination of both as the 0° orientation at larger distances wasn't tested. Logically since the products final intermolecular distances between the bonding carbons was 2.17117 Å and 2.16193 Å for exo and endo respectively, it is most likely that the orientation was the factor that affected the ability to optimise to a Transition state.

(TS calculations are very sensitive to orientation. I find the most effective method is to start with the product and increase the lengths of the bonds to a suitable length, using ModRedundant if that fails Tam10 (talk) 17:21, 10 January 2016 (UTC))

The endo transition state shown in the table below has an energy of -0.05150450 hartrees whereas the exo has an energy of -0.05041972 hartrees From this one can determine that the endo transition state is the lowest in energy and thus most stable. This is consistent with the endo rule[5]. This however is contrary to initial expectations as one would generally expect that the exo product would in fact be the most thermodynamically stable and thus the lowest in energy. The Exo transition state is potentially less favourable due to overlap of different phase orbitals, this can be seen in the HOMO, which can result in strain of the bonds. There is also potential for secondary orbital overlap interactions[6] between the MOs of the diene and the -(C=O)-O-(C=O)- fragment but due to the orientation of the C=C relative to the maleic anhydride fragment in the exo transition state, this isn't possible as they are not aligned.

(What is the endo rule? Also you seem to be mixing up kinetics and thermodynamics here Tam10 (talk) 17:21, 10 January 2016 (UTC)) (What about secondary orbital overlap in the endo TS? Tam10 (talk) 17:21, 10 January 2016 (UTC))

| Exo product | Endo Product |

|---|---|

|

|

Below the imaginary frequencies at the transition states for exo and endo can be seen respectively. Once again the JSmol animations display the single imaginary frequencies indicative of a transition state with the correct respective orientations of the molecules relative to each other and the forming/breaking of bonds displayed by the oscillating distance between the carbons.

| Exo Imaginary Frequency | Endo imaginary Frequency | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

In the table below the MOs for both the Exo and endo products.

| Exo HOMO | Exo LUMO | Endo HOMO | Endo LUMO |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

As mentioned previously due to only having the correct screenshots for one of the reactants involved for the reaction it hard to assign the combination of the MOs required to form those in the products.

Conclusion

Overall this experiment can be considered successful, the initial part of the tutorial in which anti, gauche, gauche3 and anti2 conformers were created and optimised using the HF/3-21G method produced ideal results with the energies and geometries matching those in the script to a high degree of accuracy. This was also the case with the reoptimised anti2 conformer which was carried out via B3LYP/6-31G*. The second part of the tutorial also produced expected results and trends, the frozen bonds remained at the correct distances, the chair and boat transition structures were produced using multiple methods such as QST2 and the activation energies calculated at the end were nearly identical to the script as well as being reasonable close to the experimental values in the case of the 6-31G* optimised transition states. Finally the methods previously were combined to create a Diels Alder Cycloaddition successfully. The only major error to occur was the screenshotting of the incorrect Cyclohexadiene MOs which given some extra time or if caught earlier could've been easily remedied. In order to improve/elaborate on this experiment more in future some suggestions would be to attempt to use more complex dienes/dienophiles to see how that would affect the energy values i.e by including electron withdrawing groups branching off.

References

1. Grimes R. W., Catlow C.R.A.. Quantum Mechanical Cluster Calculations in Solid State Studies. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd; 1992.

2. Hasanein A.A., Evans M.W. Computational Methods in Quantum Chemistry, Volume 2: Quantum Chemistry. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd; 1996.

3. Fox M.A., Whitesell J. K. Organic Chemistry, 3rd ed. Sudbury, Massachusetts: Jones and Bartlett Publishers; 2004.

4. Deza M.M., Deza E. Encyclopedia of Distances. : Springer; 2009.

5. Carruthers W. Some Modern Methods of Organic Synthesis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1971.

6. Gilchrist T.L., Storr R.C. Organic Reactions and Orbital Symmetry, 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1979.

Appendix

Anti 3-21G: File:REACTANTITEST321.LOG

Gauche 3-21G: File:JB713GAUCHE.LOG

Gauche3 3-21G: File:JB713GAUCHE3.LOG

Anti2 3-21G: File:JB713ANTI2321FREQ.LOG

Anti2 6-31G*: File:JB713ANTI2631FREQ.LOG

Allyl Fragment 3-21G: File:JB713ALLYLFRAGMENT2.LOG

Chair 3-21G: File:JB713CHAIRTSHF321GBERNY.LOG

Frozen Chair: File:JB713C.LOG

Derivative Chair: File:JB713D.LOG

Failed Boat: File:JB713EFAIL2.LOG

Boat 3-21G: File:JB713BOATE2.LOG

Chair 6-31G*: File:JB713CHAIR631TSBERNYFINAL.LOG

Boat 6-31G*: File:JB713BOAT631.LOG

Butadiene AM1: File:JB713CID BUTADIENE AM1.LOG

Ethylene AM1: File:JB713ETHYLENEOPTAM1.LOG

Transition state: File:JB713TSPT2AM1.LOG

1,3-Cyclohexadiene: File:JB713CYCLOHEXADIENEAM1CORRECT.LOG

Maleic Anhydride: File:JB713MALEICAM1.LOG

Exo product: File:JB713EXO QST2 AM1.LOG

Endo product: File:JB713QST2 ENDO.LOG