Rep:Mod:Ivona1Ciss11

Module 1C: Part One

Hydrogenation of Cyclopentadiene Dimers

Molecular mechanics was used to assess the energies of the endo and exo products of dimerisation in order to assess the thermodynamically more stable product. One double bond of the dimer was then hydrogenated, and the energy compared with the hydrogenated product of the other double bond to assess which of the double bonds in the cyclopentadiene dimer was the thermodynamic product of hydrogenation.

Endo and Exo Products of Dimerisation

Avogadro was used to draw and optimise the structures of the endo and exo products of dimerisation using an MMFF94s force field. The results along with illustrations of each of the products are depicted below.

| ' | (1) Exo [kcal/mol] | (2) Endo[kcal/mol] | (3) [kcal/mol] | (4) [kcal/mol] |

| Stretching Energy | 3.54342 | 3.46799 | 3.30951 | 2.82312 |

| Bending Energy | 30.77212 | 33.18881 | 30.90358 | 24.68534 |

| Torsion Energy | -2.73165 | -2.94977 | 0.02961 | -0.37843 |

| Van der Waals Energy | 12.80257 | 12.35907 | 13.27234 | 10.63736 |

| Electrostatic Energy | 13.01369 | 14.18493 | 5.12086 | 5.14702 |

| Total Energy | 55.3734 | 58.19067 | 50.7227 | 41.25749 |

Firstly, it must be noted that the energies computed refer to a deviation from normality, and therefore only stereoisomers can be compared.

Upon looking at the energies of (1) and (2), the exo and endo products of the Diels-Alder [4+2] cycloaddition of cyclopentadiene respectively, it can be stated that (2), the exo product, is more thermodynamically stable as it has an energy 2.82 kcal/mol lower than that of the endo stereoisomer. The main source of this instability can be seen to lie in the angle bending energy term, possibly resulting from increased steric strain where the two large rings lie closer together and therefore distort away from favourable bond angles in order to avoid steric interferences.In light of the fact that the endo product is produced solely in laboratory experiment, the dimerisation of cyclopentadiene must occur under kinetic control, meaning that the transition state in forming the endo dimer must be far lower in energy than that of the exo; the transition state is stabilized [1]. This is seen in the interaction of the pi bonds, not involved in the cycloaddition, of the dienophile with those of the diene, therefore lowering the energy of the transition state.

Hydrogenation Products and Hyperstable Alkenes

A similar analysis was performed upon (3) and (4) to deduce which double bond in (2) is thermodynamically more favourable to hydrogenate. It can be seen by the above data that (4) is the thermodynamically favoured product of hydrogenation of 2, therefore, the double bond in the cyclohexene ring in (2), is easier to hydrogenate than that of the cyclopentene ring. Again the main difference in energy between the two is seen to be concentrated largely in the angle bending term of the energy. This can be rationalised through analysis of the bond angles around the sp2 carbon both (3) and (4). In (3) bond angles are seen to be 126.8, whereas in (4) they are 124.5, closer to the prefered 120 for sp2 hybridisation. This is also seen to agree with experiment where the double bond of the cyclohexane ring is hydrogenated before the other. [2]

Atropisomerism in an Intermediate Related to the Synthesis of Taxol

Atropisomerism is a phenomenon whereby stereoisomers result from restricted rotations around single bonds due to a barrier resulting from steric strain. The intermediates (9) and (10) are examples of atropisomers. Both were drawn in Avogadro and molecular mechanics was used to calculate their energies to investigate the more stable isomer. Both chair conformations of each isomer were drawn to find the lowest energy structure, with the carbonyl carbon occupying either an axial position on the cyclohexane ring, or an equatorial. The results of the calculations are tabulated below.

| ' | (9) carbonyl eq. [kcal/mol] | (9) carbonyl ax. [kcal/mol] | (10) carbonyl eq. [kcal/mol] | (10) carbonyl ax. [kcal/mol] |

| stretching | 7.68316 | 8.23916 | 7.70477 | 7.50227 |

| angle bending | 31.31554 | 36.99148 | 18.86926 | 24.06748 |

| stretch bend | -0.02935 | -0.01039 | 0.03724 | -0.04159 |

| torsional | -3.00874 | -2.62202 | 1.9588 | -3.68005 |

| out of plane bend | 0.95082 | 2.04286 | 0.66281 | 0.87891 |

| van der waals | 34.00301 | 35.78762 | 34.97817 | 34.1507 |

| electrostatic | 2.62225 | 2.24288 | 2.43596 | 2.0836 |

| total | 73.53671 | 82.67159 | 66.64703 | 64.96132 |

It can clearly be seen from the above table that stereoisomer (10) is the more stable with lower energy values for both of the chairs of the cyclohexane ring, with the lowest energy being that with the carbonyl group occupying an axial position on the ring. The main difference between the 2 stereoisomers can be seen to arise from the angle bending energy terms, with differences between (9) and (10) being in the order of magnitude of approximately 10 kcal/mol. This can be explained by the strained bond angles around the carbonyl carbon in the molecule. Isomer (10) exhibits bond angles of the optimal 120° whereas molecule (9) is forced to adopt C-C-O angles of ~ 117°. The first Jmol depicts (9) with the one below depicting (10).

Taxol Intermediate 10, Co Equatorial |

Taxol Intermediate 10, Co Axial |

Spectroscopic Simulation of an Intermediate Related to Taxol Synthesis

Molecule (18) is a derivative of structure (10) analysed above. Molecule (18) was chosen for analysis following the fact that the more more favourable atropisomer was the one with the carbonyl group 'pointing down'. As above, the structure was drawn in Avogadro and optimised using an MMFF94s force field. It was found that a boat conformation in the cyclohexane ring was actually more favourable than a chair conformation. [Boat had a value of 104 kcal/mol, whereas the chair was 105 kcal/mol, a kcal higher in energy and therefore a less favourable conformation]. This may be rationalised by the fact that in the chair conformation, the methyl group attached to the cyclohexane ring is forced to be closer to the methyl groups attached to the bridging methylene. The structures of the boat conformer and the chair conformer.

As can be seen, there is a rather good agreement between literature and computed values, with discrepancies mainly arising from the reported "multiplets" in literature. Furthermore, the molecule may not have been fully optimised and therefore could contribute to minor differences in chemical shift values. Nevertheless, the peaks all seem to be in the correct regions of the spectra and therefore show the structure to be computed accurately.

| Computational [1H NMR] | ' | Literature[3] | ' | Computational [13C NMR] | Literature[3] |

| chemical shift (ppm) | Integration | chemical shift (ppm) | Integration | chemical shift (ppm) | chemical shift (ppm) |

| 0.9 | 3 | 1.03 | 3 | 22.46 | 19.83 |

| 0.98 | 1 | 1.07 | 3 | 22.61 | 21.39 |

| 1.13 | 1 | 26.64 | 22.21 | ||

| 1.36 | 1 | 26.91 | 25.35 | ||

| 1.41 | 1 | 1.1 | 3 | 28.99 | 25.56 |

| 1.52 | 4 | 1.20 - 1.50 | 3 | 29.01 | 30 |

| 1.72 | 1 | 31.36 | 30.84 | ||

| 1.78 | 2 | 1.58 | 1 | 36.38 | 35.47 |

| 1.92 | 1 | 1.70-2.20 | 6 | 38.49 | 36.78 |

| 1.97 | 1 | 44.16 | 38.73 | ||

| 2.06 | 2 | 45.44 | 40.82 | ||

| 2.18 | 1 | 46.24 | 43.28 | ||

| 2.31 | 2 | 49.72 | 45.53 | ||

| 2.4 | 2 | 2.35-2.70 | 4 | 52.52 | 50.94 |

| 2.57 | 1 | 54.04 | 51.3 | ||

| 2.73 | 2 | 2.70-3.00 | 6 | 56.3 | 60.53 |

| 2.97 | 1 | 95.64 | 74.61 | ||

| 3.05 | 2 | 119.94 | 120.9 | ||

| 3.37 | 1 | 147.65 | 148.72 | ||

| 3.45 | 1 | 211.06 | 211.49 | ||

| 5.53 | 1 | 5.21 | 1 |

Module 1C: Part 2

Crystal Structures of the Catalysts

The crystal structures of both the Shi and Jacobsen asymmetric catalysts were investigated in order to discover any interesting features of the molecules. The Cambridge Crystallographic Database was searched using the program Conquest in order to find the structures of each, which were then opened in the program Mercury to obtain 3D images of the structures. These were then analysed using the Jmols shown below.

Crystal Structure of the Shi Catalyst for Asymmetric Epoxidation

Shi Catalyst |

Upon analysis of the C-O bond lengths in the above crystal structure of the Shi pre-catalyst, the anomeric effect is clearly manifested within the 5-membered ring. The two C-O bond lengths of the 6-membered ring are seen to be the same at 0.142 nm, however the C-O bond lengths at the anomeric centre of the 5-membered ring are seen to differ by 0.003 nm. This is explained by σLP O/σ*C-O conjugation, resulting in a lengthening of the C-O bond since electron density is being placed in a C-O antibonding orbital, therefore reducing the bond order and lengthening the bond.

Crystal Structure of the Jacobsen Catalyst for Asymmetric Epoxidation

Jacobsen Catalyst |

The hydrogen atoms highlighed in purple in the Jmol above are clearly seen to be within the Van der Waal's attractive region, the optimal attractive distance being 0.24 nm, twice the Van der Waals radius of the hydrogen atom, along with repulsive interactions being distances of < ~0.21 nm. With the non-bonded distances of the hydrogen atoms being between 0.23 and 0.25 nm, these lie well within the attractive region, therefore effectively blocking approach of an alkene on this side of the catalyst, along with the steric repulsions expected from the bulky tBu groups and the alkene.

Calculated NMR for Products of Epoxidations

As with molecule (18) above, the NMR spectra were simulated for the two epoxides formed as a result of the asymmetric epoxidation of 1,2-dihydronaphthalene and trans-β-methylstyrene and compared with literature values in order to determine their structures. It must be noted that enantiomers cannot be distinguished in NMR spectra, and therefore absolute configurations cannot be obtained by comparison of the NMR spectra to literature values.

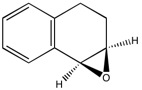

C and H NMR for Epoxidation of Dihydronaphthalene (Epoxide (1))

Epoxide (1) was drawn and optimised as before in Avogadro using an MMFF94s force field, and then later Gaussian was used to calculate an NMR spectrum, both a 13C and a 1H spectrum.

It can clearly be seen from the comparison of computed values of chemical shifts to literature values there is good agreement between the values and therefore suggest the structure proposed to be a good depiction of the epoxide synthesised.

| Computation [1H NMR] | ' | Literature[4] | ' | Computation [13C NMR] | Literature[4] |

| chemical shift (ppm) | Integration | chemical shift (ppm) | Integration | chemical shift (ppm) | chemical shift (ppm) |

| 1.56 | 1 | 1.65 | 1 | 24.95 | 21.8 |

| 2.22 | 1 | 2.3 | 1 | 28.04 | 24.4 |

| 2.26 | 1 | 2.44 | 1 | 54.83 | 52.7 |

| 2.88 | 1 | 2.68 | 1 | 56.44 | 55.1 |

| 3.56 | 1 | 3.62 | 1 | 121.44 | 126.1 |

| 3.6 | 1 | 3.74 | 1 | 123.43 | 128.4 |

| 7.19 | 1 | 6.98 | 1 | 123.84 | 128.4 |

| 7.36 | 1 | 7.08-7.17 | 2 | 125.55 | 129.5 |

| 7.4 | 1 | 130.38 | 132.6 | ||

| 7.49 | 1 | 7.28 | 1 | 133.84 | 136.7 |

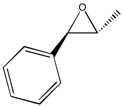

C and H NMR for Epoxidation of trans-β-methylstyrene (Epoxide (2))

Similarly, NMR spectra, as per method used above, were computed for epoxide (2) again with good agreement with literature, only discrepancies arising again with the multiplet in the aromatic region of the 1H NMR spectrum, likely due to coupling and therefore literature values being harder to analyse.

| Computation [1H NMR] | ' | Literature[5] | ' | Computational [13C NMR] | Literature[5] |

| chemical shift (ppm) | Integration | chemical shift (ppm) | Integration | chemical shift (ppm) | chemical shift (ppm) |

| 0.72 | 1 | 1.43 | 3 | 18.84 | 17.8 |

| 1.59 | 1 | 60.58 | 58.9 | ||

| 1.68 | 1 | 63.32 | 58.4 | ||

| 2.79 | 1 | 3.12 | 1 | 118.49 | 125.4 |

| 3.41 | 1 | 3.55 | 1 | 122.73 | 127.9 |

| 7.31 | 1 | 7.27 | 5 | 123.33 | 128.3 |

| 7.42 | 1 | 124.07 | 137.7 | ||

| 7.49 | 3 | 134.98 |

Assigning Absolute Configurations of Epoxides

The optical rotations of the epoxides produced were also computed in order to inspect whether the correct enantiomer was indeed calculated. As seen in the below table, the correct enantiomers were drawn to begin with as both match in both sign and magnitude to optical rotations of the epoxides reported in literature.

| ' | Computational (deg) | Literature (deg) |

| Epoxide (1) | -155.81 | -144.9[6] |

| Epoxide (2) | 46.77 | 47[7] |

Investigation of Non-Covalent Interactions in the Active-Site of the Transition State

Arrow 1 clearly depicts a covalent interaction, the blue colour being strongly attractive and therefore shows the point at which the epoxide is being formed. Arrow 2 shows more mild attractive interactions, depicted by the green surface. These therefore show a favourable non covalent attractive interactions surrounding the point at which the new C-O bonds are being formed and therefore represent how the transition state is stabilised to a degree by these non covalent attractive interactions.

Investigation of Electronic Topology (QTAIM) in the Active-Site of the Transition State

Here, the arrows depicted show weak, non-covalent bonds forming between oxygens and hydrogens in the transition state, again a source of stabilisation, along with the NCIs depicted above with the Shi catalyst and 1,2-dihydronaphthalene. The other yellow dots depicted show the covalent bonds between the atoms in each molecule.

Potential New Candidates for Investigation

Reaxys was used to search for epoxides with optical rotations of greater then 500 degrees. The following molecule cis-R-(+)-pulegone oxide has a reported value of 853.9 degrees[8], and therefore could be fit for a similar examination of the type performed in this experiment, furthermore, as the paper was written in 1963, there is large potential that the optical rotation has not in fact been computed.

References

- ↑ P. Caramella, P. Quadrelli, L. Toma, "An Unexpected Bispericyclic Transition Structure Leading to a 4+2 and 2+4 Cycloadducts in the Endo Dimerization of Cyclopentadiene", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2002, 124, 1130-1131.DOI:10.1021/ja016622h

- ↑ G. Liu, Z. Mi, L. Wang, X. Zhang, "Kinetics of Dicyclopentadiene Hydrogenation over Pd/Al2O3", Ind. Eng. Chem. Res., 2005, 44, 3846-3851.DOI:10.1021/ie0487437

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Spectroscopic data: L. Paquette, N. A. Pegg, D. Toops, G. D. Maynard, R. D. Rogers, J. Am. Chem. Soc.,, 1990, 112, 277-283. DOI:10.1021/ja00157a043

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 K. Smith, C. H. Liu, G. A. El-Hiti, "A novel supposrted Katsuki-type (salen)Mn Complex for Asymmetric Epoxidation", Org. Biomol. Chem., 2006, 004, 917-927.DOI:10.1039/B517611P

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 H. Hachiya, Y. Kon, Y. O, K. Takumi, N. Sasagawa, Y. Ezaki, K. Sato, "Unique Salt Effect on Highly Selective Synthesis of Acid-Labile Terpene and Styrene Oxides with a Tungsten/H2O2 Catalytic System Under Acidic Aqueous Conditions", Synthesis., 2012, 44, 1672-1678.DOI:10.1055/s-0031-1290948

- ↑ H. Sasaki, R. Irie, T. Hamada, K. Suzuki, T. Katsuki, "Rational Design of Mn-salen catalyst (2): Highly enantioselective epoxidation of conjugated cis olefins", Tetrahedron., 1994, 50, 11827-11838.DOI:10.1016/s0040-4020(01)89298-x

- ↑ G. Fronza, C. Fuganti, P. Grasselli, A. Mele, "The mode of bakers' yeast transformation of 3-chloropropiophenone and related ketons. Synthesis of (2S)-[2-2H]propiophenone, (R)-fluoxetine, and (R)- and (S)-fenfluramine", J. Org. Chem., 1991, 56, 6019-6023.DOI:10.1021/jo00021a011

- ↑ W. Reusch, C. K. Johnson, "The Pulegone Oxides", J. Org. Chem., 1963, 28,2557-2560.DOI:10.1021/jo01045a016