Rep:Mod:InorgComp

EX3

BH3 Section

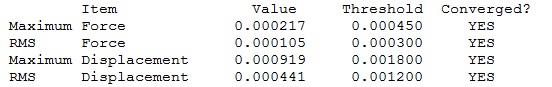

BH3:B3LYP/3-21G

Optimisation Log File

| Summary Data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Optimised BH3 Molecule |

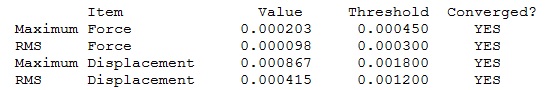

BH3:B3LYP/6-31G

Optimisation Log File

| Summary Data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Optimised BH3 Molecule |

Frequency Log File

| Summary Data | Low Modes |

|---|---|

|

Vibrational Spectrum for BH3

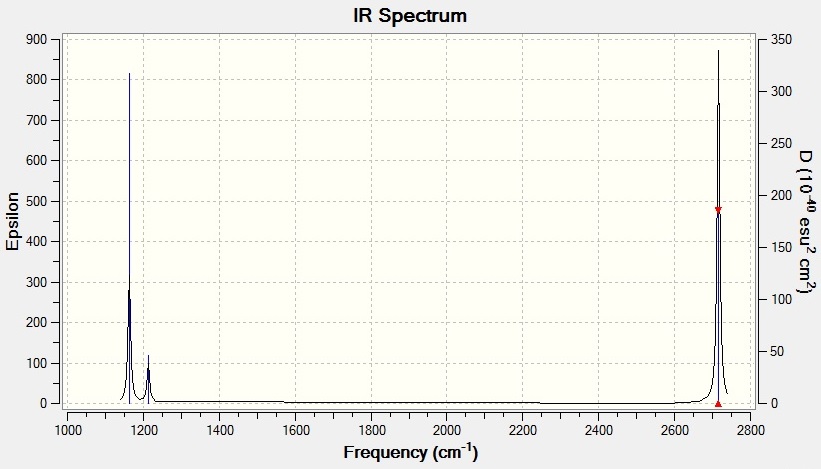

| Wavenumber | Intensity | IR Active? | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1163 | 93 | Yes | Bend |

| 1213 | 14 | Yes | Bend |

| 1213 | 14 | Yes | Bend |

| 2583 | 0 | No | Stretch |

| 2716 | 126 | Yes | Stretch |

| 2716 | 126 | Yes | Stretch |

IR Spectrum for BH3

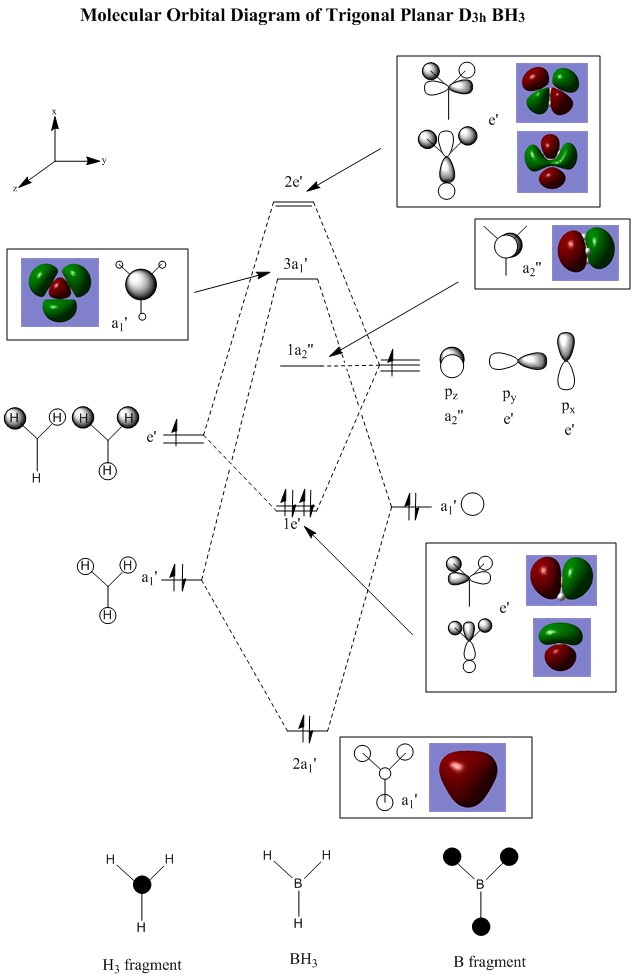

BH3 Molecular Orbitals DOI:10042/31376

There are no significant differences between the real and LCAO MOs therefore qualitative MO theory is fairly accurate and useful.

GaBr3 Section

GaBr3:B3LYP/LANL2DZ

Optimisation Log File: DOI:10042/31161

| Summary Data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Optimised GaBr3 Molecule |

Frequency Log File: DOI:10042/31255

| Summary Data | Low Modes |

|---|---|

|

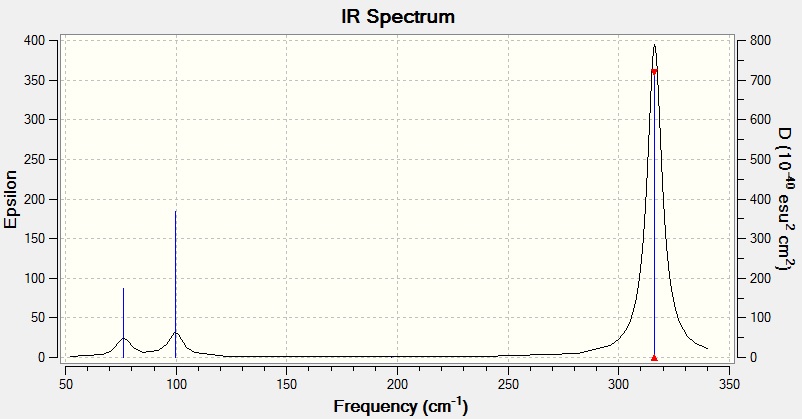

Vibrational Spectrum for GaBr3

| Wavenumber | Intensity | IR Active? | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 76 | 3 | Yes | Bend |

| 76 | 3 | Yes | Bend |

| 100 | 9 | Yes | Bend |

| 197 | 0 | No | Stretch |

| 316 | 57 | Yes | Stretch |

| 316 | 57 | Yes | Stretch |

IR Spectrum for GaBr3

IR Spectra Analysis

Only three peaks are visible on the IR spectra even though there are six vibrations due to degeneracy and intensity. There are two pairs of degenerate (equal frequency and intensity) stretches for both molecules. These appear on the IR spectra on the same peaks therefore one single peak represents one pair of degenerate stretches. In addition, there is also one IR inactive stretch for each molecule which does not appear on either spectrum as the vibration is not sufficiently intense to be detected.

As you can see from the vibrational spectra carried out on BH3 and GaBr3 there is a large difference in both frequency and intensity. The vibrational spectrum for GaBr3 has far smaller frequencies than that run on BH3. This is due to the bond strengths and molecular weights of both molecules.

GaBr3 has a weaker bond compared to that of BH3 as discussed below. Ga and Br are much larger than B and H hence the orbital overlap in GaBr3 is less efficient than in BH3 causing GaBr3 to have a lower bond strength. In a weaker bond the atoms are further apart so they do not vibrate with such a high frequency which explains why GaBr3 has a lower frequency range.

However the molecular weights of GaBr3 and BH3 play a far more important role in determining the frequencies of their molecular vibrations. The frequency of vibrations is dependent on both the force constant, k and the reduced mass, μ according to Equation (1).

From Equation (1) it can be seen that the frequency is inversely proportional to the reduced mass (2). Therefore because GaBr3 has a greater molecular weight than BH3 the vibrational frequencies for GaBr3 are at a lower than for BH3 molecular vibrations.

The umbrella motion is an angle deformation that occurs out of the symmetry plane on the molecule with symmetry label σh. It depends on the rigidity of the molecule and its bond strengths. As we can see from the IR data, the umbrella motion frequency value for BH3 is greater than the other angle deformation that occurs. On the other hand, the umbrella motion frequency value for GaBr3 is smaller than the other angle deformation it undergoes. This is because the bond strength of BH3 is larger than that of GaBr3 so BH3 is stiffer and has a stronger planar preference making the bonds vibrate at a higher frequency than in GaBr3 to bend back to their original symmetry (trigonal planar). For both molecules the intensity of the umbrella motion decreases but for BH3 it decreases by a much greater amount.

The same method and basis set for both optimisation and frequency analysis calculations must be used in order to be able to compare energies afterwards. The total energy of a calculation depends on the quality of the basis set and method used. It is impossible to compare energies of two systems by using different basis sets because each basis set has its own error associated with it. When carrying out two calculations the same basis sets, number of atoms and method must be used to be able to compare the energies.

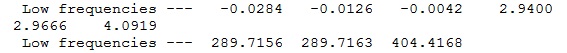

A frequency analysis is carried in order to identify where exactly on the potential energy surface (PES) the minimum is. The frequency analysis calculates the second derivative of the PES so the minimum or maximum can be found. If all the frequencies are positive then a minimum has been located and that is a stable point. This means that the optimisation of the molecule being dealt with has gone to completion. If not all the frequencies calculated are positive then a transition state has been found.

All atoms have 3N-6 vibrational frequencies where N is the number of atoms. “-6” are the “Low Frequencies” that are the 3 rotational and 3 translation degrees of freedom of the mass of the molecule. If these frequencies are negative it does not affect the calculations carried out on the molecule. However, these values must be close to zero in order to minimise the molecule’s degrees of freedom.

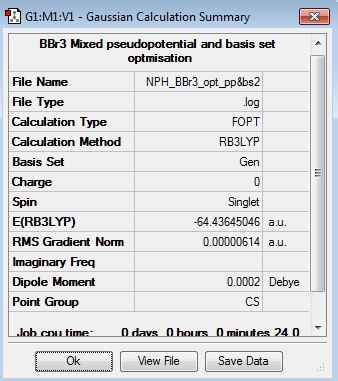

BBr3 Section

BBr3:B3LYP/6-31G(d,p)LANL2DZ

Optimisation Log File: DOI:10042/31165

| Summary Data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Optimised BBr3 Molecule |

Geometry Comparison

| BH3 | BBr3 | GaBr3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| r(E-X) Å | 1.193 | 1.934 | 2.350 |

| θ(X-E-X) degrees (°) | 120.00 | 120.00 | 120.00 |

From the table above we can see that both changing the ligand and central atom of a molecule alters its bond lengths however it does not significantly change its bond angles. The three molecules above; BH3, BBr3 and GaBr3, all have the same bond angle of 120° even though the bond lengths differ noticeably. This is due to the fact that 120° is the optimum bond angle for molecules with a trigonal planar geometry. In this way, the ligands are furthest away from each other reducing the repulsive interactions between them and minimising the total energy of the molecule. However, GaBr3 has a bond length of 2.350 Å which is almost twice the bond length present in BH3 (1.193 Å) and BBr3 bond length (1.934 Å) lies between the two.

The electronic configuration of bromine (Br) is 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s2 3p6 4s2 3d10 4p5 and that of hydrogen (H) is 1s1 hence they both have 1 unpaired electron in their outer orbital. Nevertheless, Br and H behave very differently as ligands due to their size and energy. The H 1s orbital is very small as it only contains 1 electron in it causing no repulsive interactions. Furthermore, H is more electropositive compared to Br. On the other hand, Br is larger as its valence electrons occupy the 4s and 4p orbitals which are further away from the nucleus than the 1s orbital due to their higher quantum number. In addition, Br has full 3d orbitals which are core-like causing greater electron-electron repulsion within them also increasing the size.

In a molecule the change in central atom also has a great effect on the extent of bonding and bond length. Boron (B) and gallium (Ga) are both in Group 13 of the periodic table of elements thus they have similar properties. The electronic configuration of B is 1s2 2s2 2p1 and that of Ga is 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s2 3p6 4s2 3d10 4p1. These elements’ preferred oxidation states are +1 and +3 hence trivalent compounds are easily obtained. However, Ga is much larger than B due to the fact that its valence electrons reside on the 4s and 4p orbitals which lie further away from the nucleus and it has filled 3d orbitals.

Bond distance reflects bond strength; therefore a strong bond will have a shorter bond distance than a weak bond. Similar valence orbital size and energy are needed for good overlap to obtain a stronger bond. Yet atoms with smaller valence orbitals make stronger bonds as they have shorter atomic radii and overlap more efficiently. For these reasons GaBr3 has the largest bond distance; both Ga and Br are large leading to poor overlap and steric hindrance around the Ga central atom. Moreover, Ga experiences the “inert pair effect” to some extent causing it to form slightly weaker bonds. BH3 has the shortest bond length as a result of the small size of the H and B orbitals, and their similarity in energy. BBr3 bond length lies between that of BH3 and GaBr3 due to the difference between B and Br orbital size however they do not differ largely in electronegativity.

A chemical bond is an electrochemical interaction between two atoms that attract each other. As two atoms approach each other the electrons around the nucleus of one atom are attracted to the protons in the nucleus of the other and vice versa causing an electrochemical interaction. There are different types of chemical bonds; strong and weak ones.[1] Strong chemical bonds include covalent and ionic bonds, and weak bonds include dipole-dipole interactions, London dispersion forces, hydrogen-bonds, dative bonds, etc. In ionic bonds it is the Coulombic attraction between the two oppositely charged atoms that causes an electrostatic interaction, also called chemical bond. On the other hand, in a covalent bond a pair of electrons is shared between two atoms to satisfy the “Eight Electron Rule” and stabilise each other. Multiple bonds also exist whereby more than one pair of electrons is held between two atoms to satisfy the rule. Hence, if more electron pairs are held between two atoms there will be more charge between them so there will be a stronger electrochemical interaction. A way to measure bond strength is by measuring bond dissociation energies of different bonds. A bond with a large dissociation energy is a strong bond as a lot of energy must be put in to it to break the two atoms apart, for example N≡N 945.42 kJ/mol (298 K) compared to C-H 339.0 kJ/mol (298 K), a weak bond.[2]

In some structures GaussView does not draw bonds between atoms however this does not mean there is no bond. GaussView does not draw bonds based on chemical interactions but based on distance. Yet these distances are predefined values based on organic molecules hence when the distance between two atoms is larger than the predefined value for a bond GaussView does not draw one.

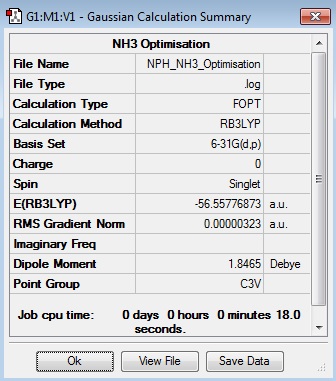

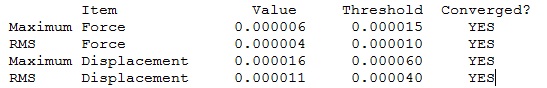

NH3 Section

NH3:B3LYP/6-31G(d,p)

Optimisation Log File

| Summary Data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Optimised NH3 Molecule |

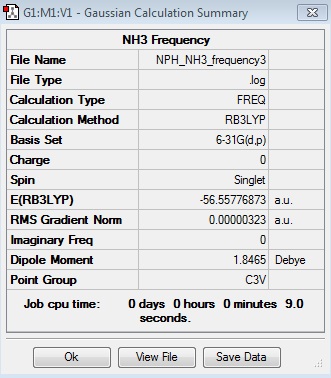

Frequency Log File

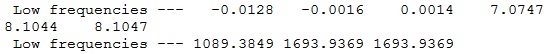

| Summary Data | Low Modes |

|---|---|

|

|

NH3 Molecular Orbitals DOI:10042/31375

NBO Analysis

| Summary Data | Charge Distribution | NBO Charges |

|---|---|---|

|

|

Nitrogen: -1.125 e

Hydrogen: 0.375 e |

NH3BH3 Section

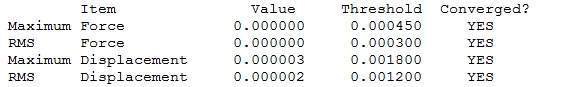

NH3BH3:B3LYP/6-31G(d,p)

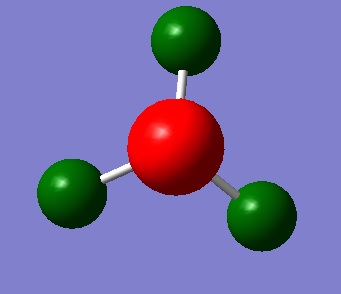

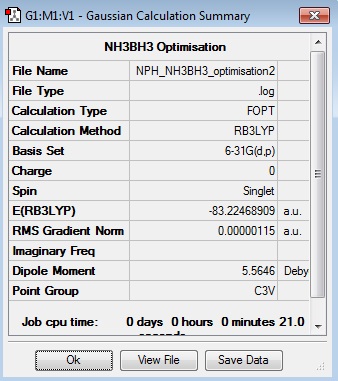

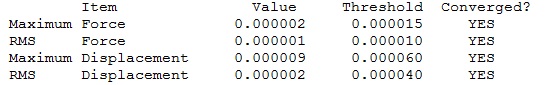

Optimisation Log File

| Summary Data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Optimised NH3BH3 Molecule |

Frequency Log File

| Summary Data | Low Modes |

|---|---|

|

|

B-N Bond Strength

| Energy (a.u.) | Energy (kJ/mol) | |

|---|---|---|

| NH3 | -56.5577687 | -148492.43 |

| BH3 | -26.6153235 | -69878.54 |

| NH3BH3 | -83.2246891 | -218506.44 |

| BN | -0.0515969 | -135.47 |

The association of NH3 and BH3 to form a B-N bond within NH3BH3 is unusually small. This could be explained by the fact that B-N was formally a dative bond.

Mini-project: Aromaticity

Benzene Section

C6H6:B3LYP/6-31G(d,p)

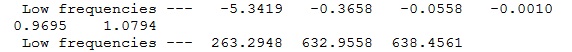

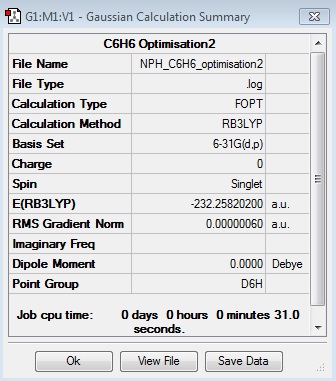

Optimisation Log File

| Summary Data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Optimised C6H6 Molecule |

Frequency Log File

| Summary Data | Low Modes |

|---|---|

|

|

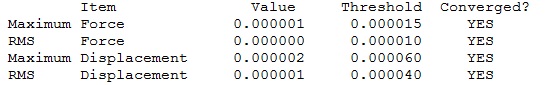

Molecular Orbitals DOI:10042/31377

Aromaticity is the property by which a system becomes more stable due to the ability of electrons in p-orbitals to delocalise over a planar structure. There are three main requirements for aromaticity; the molecule must be planar with p-orbitals perpendicular to the ring, it must be cyclic and it must satisfy Huckel’s Rule. Benzene perfectly satisfies all these rules and therefore it is one of the most important aromatic molecules as it is so unreactive due to this phenomenon. However, the classical way of thinking of benzene is as a six membered ring with six sp2 hybridised carbons all bonded to a hydrogen with a p-orbital containing one electron perpendicular to the plane of the ring.

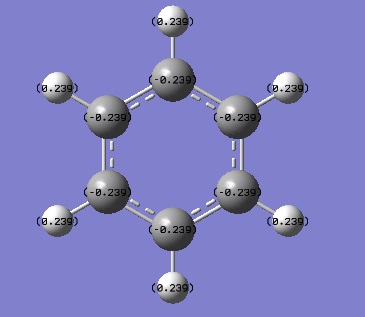

NBO Analysis

| Summary Data | Charge Distribution | NBO Charges |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Tabulated NBO Charges

| Atom | Charge (e) |

|---|---|

| C(1) | -0.239 |

| C(2) | -0.239 |

| C(3) | -0.239 |

| C(4) | -0.239 |

| C(5) | -0.239 |

| C(6) | -0.239 |

| H(1) | 0.239 |

| H(2) | 0.239 |

| H(3) | 0.239 |

| H(4) | 0.239 |

| H(5) | 0.239 |

| H(6) | 0.239 |

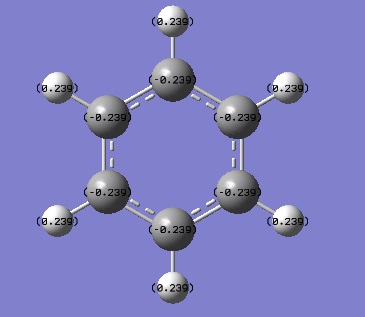

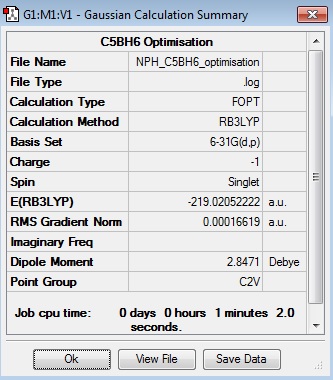

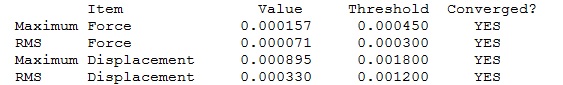

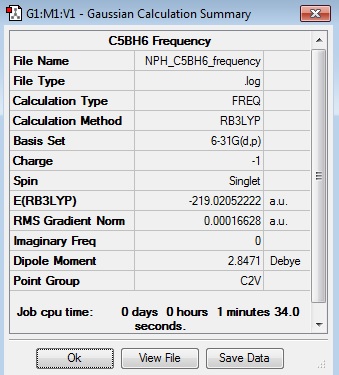

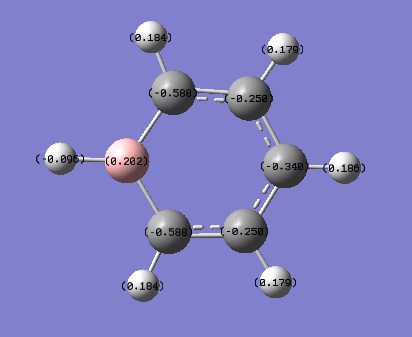

Boratabenzene Section

C5BH6:B3LYP/6-31G(d,p)

Optimisation Log File

| Summary Data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Optimised C5BH6 Molecule |

Frequency Log File

| Summary Data | Low Modes |

|---|---|

|

|

Molecular Orbitals DOI:10042/31378

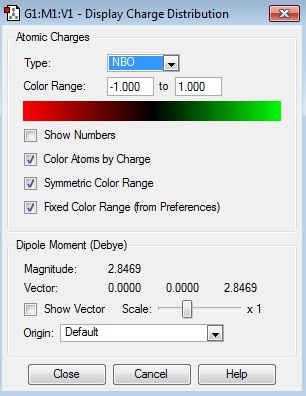

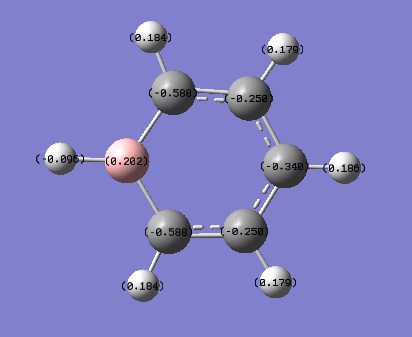

NBO Analysis

| Summary Data | Charge Distribution | NBO Charges |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Tabulated NBO Charges

| Atom | Charge (e) |

|---|---|

| C(1) | -0.250 |

| C(2) | -0.340 |

| C(3) | -0.250 |

| C(4) | -0.588 |

| C(5) | -0.588 |

| H(1) | 0.179 |

| H(2) | 0.186 |

| H(3) | 0.179 |

| H(4) | 0.184 |

| H(5) | -0.096 |

| H(6) | 0.184 |

| B | 0.202 |

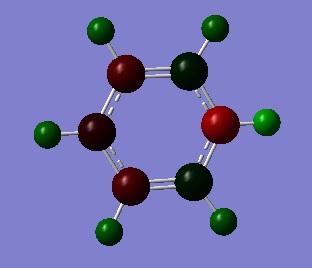

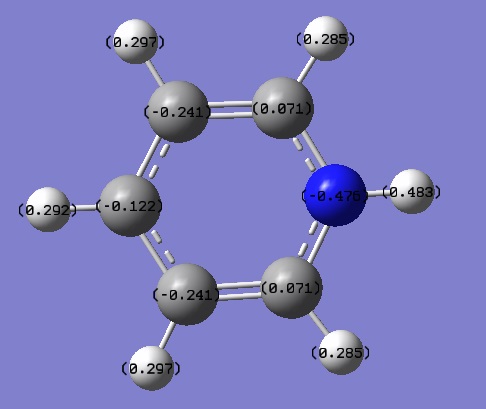

Pyridinium Section

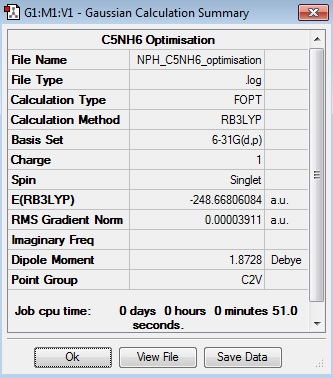

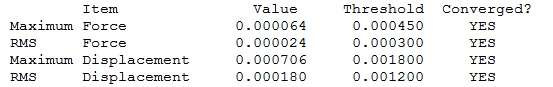

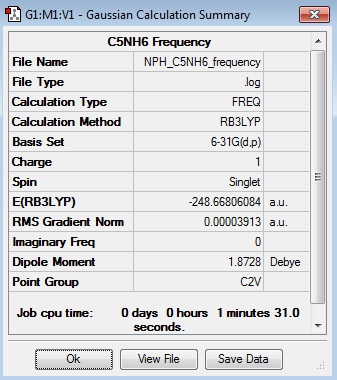

C5NH6:B3LYP/6-31G(d,p)

Optimisation Log File

| Summary Data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Optimised C5NH6 Molecule |

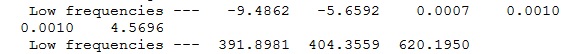

Frequency Log File

| Summary Data | Low Modes |

|---|---|

|

|

Molecular Orbitals DOI:10042/31379

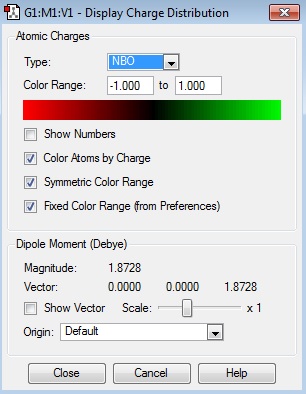

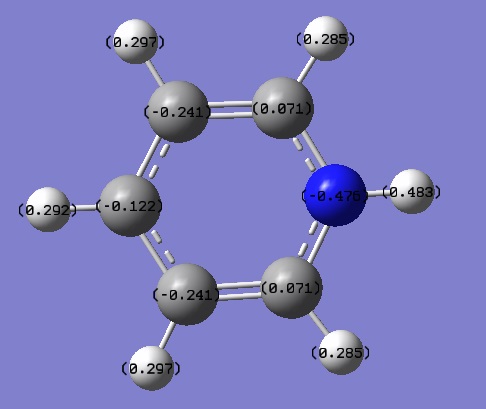

NBO Analysis

| Summary Data | Charge Distribution | NBO Charges |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Tabulated NBO Charges

| Atom | Charge (e) |

|---|---|

| C(1) | 0.071 |

| C(2) | -0.241 |

| C(3) | -0.122 |

| C(4) | -0.241 |

| C(5) | 0.071 |

| H(1) | 0.285 |

| H(2) | 0.297 |

| H(3) | 0.292 |

| H(4) | 0.297 |

| H(5) | 0.285 |

| H(6) | 0.483 |

| N | -0.476 |

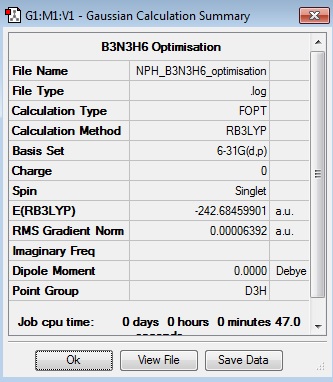

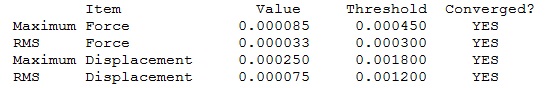

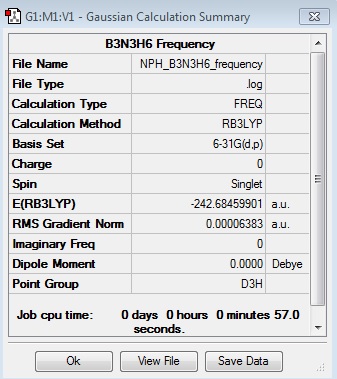

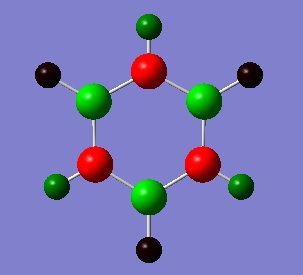

Borazine Section

N3B3H6:B3LYP/6-31G(d,p)

Optimisation Log File

| Summary Data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Optimised N3B3H6 Molecule |

Frequency Log File

| Summary Data | Low Modes |

|---|---|

|

|

Molecular Orbitals DOI:10042/31380

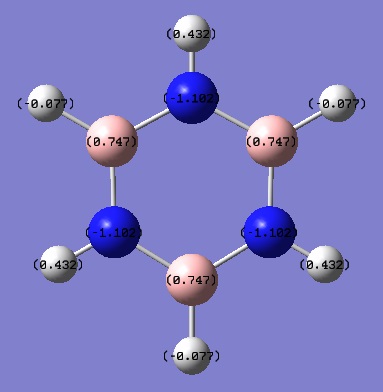

NBO Analysis

| Summary Data | Charge Distribution | NBO Charges |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

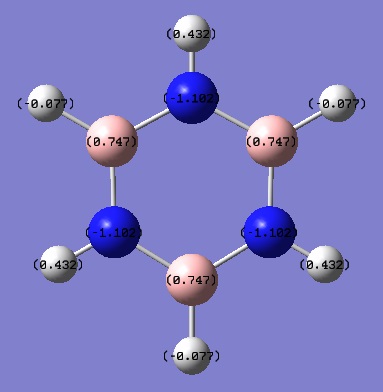

Tabulated NBO Charges

| Atom | Charge (e) |

|---|---|

| H(1) | 0.432 |

| H(2) | -0.077 |

| H(3) | 0.432 |

| H(4) | -0.077 |

| H(5) | 0.432 |

| H(6) | -0.077 |

| N(1) | -1.102 |

| N(2) | -1.102 |

| N(3) | -1.102 |

| B(1) | 0.747 |

| B(2) | 0.747 |

| B(3) | 0.747 |

Charge Distribution Analysis

| C6H6 | C5BH6 | C5NH6 | N3B3H6 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Benzene, boratabenzene, pyridinium and borazine are all isoelectronic structures however their charge distribution is not equal. This is due to the differences in electronegativity between, C, B, N and H.

In benzene the charges on C and H are equal in magnitude but opposite in sign. C has a -0.239 e charge and H has a 0.239 e charge. C is more electronegative than H hence C has a negative charge on it and H has a positive charge on it. The charge on all the Cs and Hs is identical in every position around the benzene ring because the molecule is symmetrical.

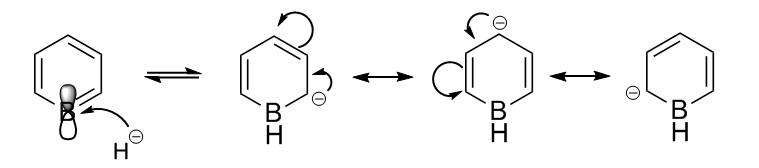

On the other hand, on boratabenzene the charge on the C atoms and the H atoms varies depending on whether they are in the ortho-, para- or meta- position to the B atom. The figure below shows how H is added to boratabenzene and the charge is delocalised around the ring.

B has an empty electron deficient p-orbital perpendicular to the plane of the ring. However, B cannot have four bonds so when the negatively charged H atom comes in to populate that electron deficient p orbital the double bond from B to C breaks and the negative charge shifts to the adjacent C atom. The structure oscillates between the three resonance structures above to stabilise it. This explains why the Cs at the ortho- and para- positions are more negatively charged. The Cs at the ortho- positions are more negatively charged than those at the para- position because they are adjacent to B which is the most electropositive atom in the molecule. In addition, the negative charge prefers not to reside on the B atom because it is electropositive. Moreover, the H atom attached to the B is also the most negatively charged because the B-H bond becomes polarised as B highly is electropositive.

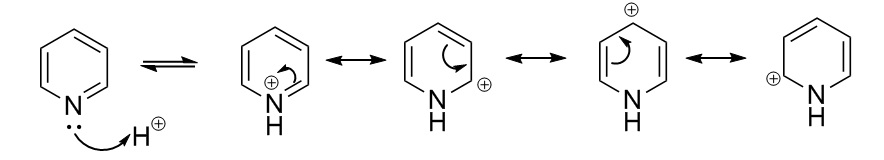

Likewise, on pyridinium the charge on the C atoms and H atoms depends on what position they are in compared to N. The figure below describes how a positively charged H cation is added on to pyridine and the charge is delocalised around the ring.

In this case the lone pair available on the N p-orbital perpendicular to the plane of the ring is used to bond with the H cation. N is electronegative therefore it is not the preferred place for positive charge to reside so the N=C double bond is broken to remove the positive charge from the N atom. The positive charge is delocalised around the ring as shown in the figure above and resides on the ortho- and para- C atoms, this is why they are more positively charged. The C atoms adjacent to the N are more positively charged than those on the para- position because they are closer to the electronegative N. Furthermore, the H bonded to the N atom is the most positively charged as the N-H bond is now polarised due to the fact that N is the most electronegative atom in the molecule.

Borazine is sometimes referred to as "Inorganic Benzene" as it is isoelectronic with benzene and is aromatic. All the N-B bonds are the same length with sp2 B and N orbitals in the ring. This suggests overlap between the filled N 2p orbitals and the B 2p orbitals. However, from the charge distribution analysis carried out we can see that the B and N atoms have very different charges. All the N atoms are negatively charged and all the C atoms are positively charged. This is because even though the N atoms donate electron density into the empty B 2p orbitals, the B atoms always remain slightly electron deficient as N is more electronegative than B so the electrons prefer to reside closer to the N atoms. All the H atoms bonded to electronegative N atoms have a positive charge and the H atoms bonded to electropositive B atoms are negatively charge because the bonds become slightly polarised.