Rep:Mod:HLLimbrickCompLab

3rd Year Inorganic Computational Lab

EX3:

Three molecules of the formula EX3 have been optimised using the program GaussView: BH3, BBr3 and GaBr3. The resulting bond length and bond angle data for each molecule has then been compared in order to investigate the effect of ligand and central atom changes on the geometry of said molecules. All comparisons have been drawn using the data from molecules optimised using the 6-31G basis set, and additional results have been presented in the form of a summary table and log file. Frequency analysis of BH3 and GaBr3 was then performed to confirm that an energy minima was found, and the differences in vibrational spectra has been discussed.

BH3 -

| Method | Basis Set | Calculation Type |

|---|---|---|

| B3LYP | 3-21G | OPT |

Optimisation Log File can be accessed: here

| Method | Basis Set | Calculation Type |

|---|---|---|

| B3LYP | 6-31G | OPT |

Optimisation Log File can be accessed: here

| Summary Data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000007 0.000015 YES

RMS Force 0.000005 0.000010 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000027 0.000060 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000018 0.000040 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-2.803047D-10

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

|

|

GaBr3 -

| Method | Basis Set | Calculation Type |

|---|---|---|

| B3LYP | LanL2DZ | OPT |

Optimisation Log File can be accessed here:DOI:10042/85045

| Summary Data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000000 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000000 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000003 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000002 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-1.282678D-12

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

|

|

BBr3 -

| Method | Basis Set | Calculation Type |

|---|---|---|

| B3LYP | Gen (6-31G(d,p) and LanL2DZ) | OPT |

Optimisation Log File can be accessed via:DOI:10042/90467

| Summary Data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000008 0.000015 YES

RMS Force 0.000005 0.000010 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000036 0.000060 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000024 0.000040 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-4.086028D-10

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

|

|

Geometry Data -

| BH3 | BBr3 | GaBr3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| r(E-X) | 1.19 Å | 1.93 Å | 2.35 Å |

| θ(X-E-X) | 120.0o | 120.0o | 120.0o |

Analysis of results -

Bond Angle Data:

All three molecules are expected and shown to possess D3h symmetry, implying that the three ligand groups are spaced equally around the central atom; for trigonal planar molecules such as these, the sp2 bond angles are preferentially 120o.[1] This ideal bond angle is observed in all three species as they have been constrained to the D3h point group where equal bond angles are mandatory. Changing the ligands (BH3 to BBr3) and changing the central atom (BBr3 to GaBr3) cause no alterations in the bond angle observed as in each case the central atom is sp2 hybridised and bonded to three identical ligands in a trigonal planar fashion.

Bond Length Data:

A marked increase in calculated bond length is observed from left to right across the table, with both changing the ligand (BH3 to BBr3) and changing the central atom (BBr3 to GaBr3) causing the elongation of bonds. Bond lengths give an indication of the strength of interaction between two atoms and therefore the strength of the bond formed between them. The strength of a bond corresponds to the extent of which the atomic orbitals involved overlap. A strong interaction of atomic orbitals requires them to be of the same symmetry, be as close as possible in energy and be of a similar size.[2] Atomic orbitals are combined to give molecular orbitals, and these combinations can be represented qualitatively via molecular orbital diagrams. When two atomic orbitals combine, they may do so either in-phase, or out-of-phase; this gives rise to two molecular orbitals: one bonding (lower energy) and one anti-bonding (raised energy). The in-phase combination is responsible for the bonding molecular orbital, and filling this with electrons indicates a bonding interaction between the atoms involved. Filling the anti-bonding molecular orbital, however, weakens any bonding interactions due to being a high energy, destabilising occurrence. This leads to the concept of bond order:[2]

Bond order = (number of electrons in bonding MOs minus number of electrons in anti-bonding MOs)/2

A higher bond order is indicative of more electrons contributing to the bond and therefore the presence of a shorter, stronger bond.[2] The bond order for each molecule is three; this corresponds to three single bonds, and so bond order does not factor into the observed bond length changes. We instead look for other factors that may influence this such as the extent of atomic orbital overlap as previously mentioned.

1)What difference does changing the ligand have, and how are H and Br similar, how are they different?

The first two molecules in the above geometry table vary in their ligand only; a change from hydrogen to bromine ligands is shown to result in a bond length increase of 0.74 Å. An increased bond length is indicative of a weaker bond as the atoms are further apart and so held more loosely than those connected by a short bond. If we consider the bond length to be the sum of the covalent radii of the bonded atoms, it is expected that the bromine ligands will result in an increased bond length due in part to their covalent radii being far greater than that of hydrogen ligands. A further consideration comes from the molecular orbital diagrams of each molecule. Firstly, the atomic orbital energies are more mismatched for boron and bromine than they are for boron and hydrogen as a result of bromine being very electronegative. A more electronegative atom holds onto its electrons more tightly, causing the atomic orbital energy levels to be low. Both ligands are more electronegative than boron, but bromine much more so than hydrogen, this results in the overlap of bromine with boron being poor, with a small stabilisation energy and weak interaction.[1] Further more, valence orbital sizes of the two ligands are to be considered; whilst the hydrogen ligands bond via an electron in a 1s orbital (small and contracted), the bromine ligands bond via an electron in a 4p orbital. The 4p orbital is far more diffuse than the hydrogen 1s orbital, and so has a poorer overlap with the sp2 boron bonding orbitals; this poor overlap results in a weaker interaction, and thus longer bond between boron and bromine in comparison to boron and hydrogen.

2)What difference does changing the central element make, and how are B and Ga similar, how are they different?

This comparison is drawn upon data for the BBr3 and GaBr3 molecules, with the latter having the longer bond lengths. Boron and gallium belong to Group 13 of the periodic table, with boron possessing a stable macromolecular structure, and gallium a metallic structure. As you move down the group (from boron towards gallium) the s-p orbital separation increases due to the s orbital ability to penetrate closer to the nucleus and experience a greater nuclear charge. The promotional energy (s to p) therefore increases down the group, and this coupled with decreasing bond energies results in some gallium compounds existing in the +1 oxidation state. Whilst boron compounds exist solely in the 3+ oxidation state (tri-valent boron), gallium compounds may exist in the 3+ or 1+ oxidation state (tri- or mono-valent) depending on whether the energy required for promotion and hybridisation exceeds the energy released by the formation of two new bonds.[1] Since we are considering two tri-valent compounds, this does not factor into the difference in bond lengths, but gallium being further down the group does have an impact. As mentioned in the ligand discussion, the larger element, in this case gallium, has larger valence orbitals, these are more diffuse and so overlap poorly with the bromine ligands giving rise to longer, weaker bonds. In the BBr3 compound, boron is an electron deficient species, with only six valence electrons, it can, however, accept the bromine lone pair into its empty p orbital to gain a full octet and so BBr3 is a Lewis Acid[1]; this extra stabilising interaction strengthens the bonds and so they are contracted compared to values obtained via addition of covalent radii. This electron donation also causes GaBr3 to be a Lewis Acid, but again due to larger, more diffuse orbitals, the interaction is weaker and the bond lengths are contracted by a lesser amount.

3)What is a bond?

A bond is an attraction between atoms; the bond may be covalent, ionic or metallic depending on the atoms involved. In order to form a bond, the repulsion of the nuclei involved must be balanced by the attraction of each nucleus to the electrons of the other nucleus. The bond distance is the separation at which the electrons and nuclei have organised themselves so as to give a molecule free from net forces, it is the equilibrium position on a potential energy versus separation curve.[3]

4)How much energy is there in a strong, medium and weak bond? Give examples of each type of bond (strong, medium and weak)

Bond strength is determined by bond order, this takes into account the number of bonding electron pairs, with a greater number resulting in a shorter, stronger bond between the atoms involved. A high bond order denotes a stable bond that holds the atoms tightly due to greater attraction, which is in turn due to a greater number of bonding electrons. As such, bonds with a high bond order are more difficult to overcome and are typified by high bond enthalpies.[1] An example of a weak bond would be a bonding interaction rather than a covalent, ionic or metallic bond. Bonding interactions such as London dispersion forces are weak bonds. These arise due to the presence of instantaneous dipoles in neighbouring non-polar molecules. Due to fluctuations in the electron clouds of atoms, at any one point in time an instantaneous dipole may develop, this will polarize the electron clouds on nearby atoms and cause a transient bonding interaction between the two. These bonding interactions are very weak, as an example, the interaction energy between two methane molecules is only -5kJ/mol.[1] An example of a medium strength covalent bond would be C-H, this has a greatly increased bond enthalpy of 412 kJ/mol.[1] Finally, a triple bond such as NN would be considered a strong bond, this has a bond enthalpy of 946 kJ/mol.[1]

5)In some structures gaussview does not draw in the bonds where we expect, why does this NOT mean there is no bond?

The lab manual states that sometimes Gaussview gives a structure with no bonds; this is due to the tight criteria Gaussview adheres to for assigning a bond. Gaussview uses pre-assigned distances to determine bonds, and if the structure has bond distances exceeding this value, the program will not show its presence.[3]

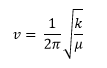

BH3 Frequency Analysis -

| Method | Basis Set | Calculation Type |

|---|---|---|

| B3LYP | 6-31G(d,p) | FREQ |

Frequency Log File can be accessed: here

| Summary Data | Low Modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -12.9674 -12.9617 -8.6264 0.0007 0.0212 0.3867 Low frequencies --- 1162.9645 1213.1322 1213.1324 |

| Wavenumber (cm-1) | Intensity | IR active? | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1163 | 93 | YES | BEND |

| 1213 | 14 | VERY SLIGHTLY | BEND |

| 1213 | 14 | VERY SLIGHTLY | BEND |

| 2583 | 0 | NO | STRETCH |

| 2716 | 126 | YES | STRETCH |

| 2716 | 126 | YES | STRETCH |

Analysis of Results -

Why are there less than six peaks in the spectrum, when there are obviously six vibrations?

From the intensities listed in the vibrational frequency table given above, it is expected that the spectrum would include three strong peaks, and two weak peaks. The infrared selection rule states that in order for a peak to appear on the spectrum, a dipole change is required to occur within the molecule during the vibration:[4]

∆v= ±1

The vibration corresponding to 2583 cm-1 does not cause a dipole moment change and so this vibrational mode is said to be inactive and no peak is seen. We are then left with two vibrations that appear to be missing. There are two sets of degenerate vibrations (1213 and 2716 cm-1) recorded in the table, each vibration from the degenerate pair would result in a peak in the same position on the spectrum, we therefore see one, more intense peak representing the two vibrational modes.

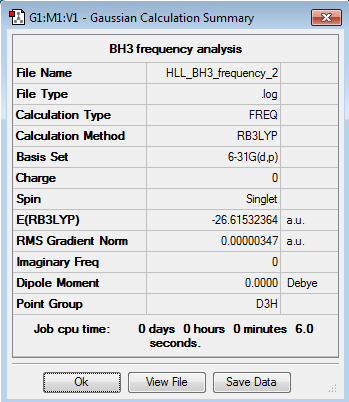

GaBr3 Frequency Analysis -

| Method | Basis Set | Calculation Type |

|---|---|---|

| B3LYP | 6-31G(d,p) | FREQ |

Frequency Log File can be accessed via:DOI:10042/90688

| Summary Data | Low Modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -1.4877 -0.0015 -0.0002 0.0096 0.6540 0.6540 Low frequencies --- 76.3920 76.3924 99.6767 |

| Wavenumber (cm-1) | Intensity | IR active? | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 76 | 3 | VERY SLIGHTLY | BEND |

| 76 | 3 | VERY SLIGHTLY | BEND |

| 100 | 9 | VERY SLIGHTLY | BEND |

| 197 | 0 | NO | STRETCH |

| 316 | 57 | YES | STRETCH |

| 316 | 57 | YES | STRETCH |

Analysis of Results-

Compare and contrast the vibrational spectra for BH3, and GaBr3.

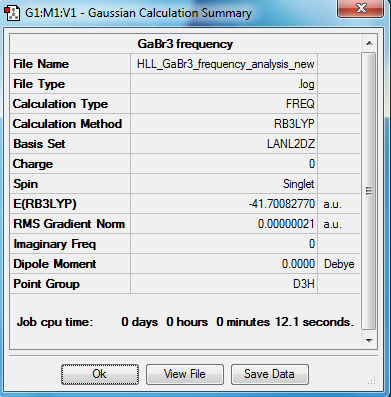

Both vibrational tables record six vibrational modes as (3N – 6) in both cases is equal to (3x4)-6 = 6. However, only three peaks appear on each spectrum; again, this is due to each molecule having one IR inactive symmetric stretching mode and two sets of doubly degenerate IR active modes which superimpose on the spectra alongside a bond angle deformation peak. In both cases the bond angle deformations occur at a lower frequency than the bond stretches as expected because bond compressions and extensions require more energy to occur.[4]

1)What does the large difference in the value of the frequencies for BH3 compared to GaBr3 indicate?

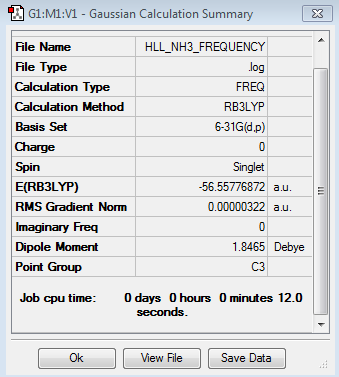

The stretching of bonds is approximated using Hooke’s Law, whereby the atoms are specified as masses connected via a spring with spring constant ‘k’. The vibrational frequencies are then given by:[1]

Here μ is the reduced mass of the two-particle system :

From this equation it is suggested that the system with the largest reduced mass would have vibrational modes at lower frequencies. This is supported by the spectra obtained, with all vibrational modes occurring at lower frequencies for the heavier system GaBr3. Furthermore, a larger value of k would cause the vibrational modes to occur at higher frequencies. The spring constant, k, is also a measure of bond strength, with stronger, stiffer bonds having larger k values.[1] From this we would expect the BH3 molecule to have higher vibrational frequencies due to having shorter, stronger bonds as identified in the geometry data section above. Both the increased bond strength and lower reduced mass of the BH3 molecule act so as to cause a spectra with higher vibrational frequencies than observed for GaBr3 and so the data obtained correlates with theory.

2)There been a reordering of modes! This can be seen particularly in relation to the A2" umbrella motion. Compare the relative frequency and intensity of the umbrella motion for the two molecules. Looking at the displacement vectors how has the nature of the vibration changed? Why?

The A2’’ umbrella modes occur at very different frequencies, 1163 cm-1 and 100 cm-1 for BH3 and GaBr3 respectively. This is accompanied by a difference in intensity – 93 and 9 respectively. In the BH3 vibrational mode, the displacement vectors are located on the hydrogen ligands, with the central boron atom remaining stationary throughout, whereas in the GaBr3 molecule, it is the central gallium atom which is displaced during the vibration. This alteration in displacement vector location is due to the relative masses of the central atom and ligands; boron is far heavier than hydrogen and so appears to be stationary with respect to their motion, and similarly the bromine ligands have a greater mass than the gallium centre in GaBr3 and so do not appear to move.[1] The intensity reflects how IR active the vibration is, and so is linked to the change in dipole moment during the displacement. It is suggested that because the umbrella mode for BH3 involves the displacement of all three ligand atoms, it results in a larger change in dipole moment and so more intense signal. As previously discussed, the umbrella vibration of BH3 has resulted in a peak at a higher frequency than that for the corresponding GaBr3 vibration due to it possessing a stonger bond (larger k) and lower reduced mass (μ).

3)Why must you use the same method and basis set for both the optimisation and frequency analysis calculations?

You may only compare results and data values obtained via using the same method and basis sets as the calculations are subject to the basis set size. The method specifies the level of approximation used to solve the Schrodinger equation, and basis sets give the number of functions used to describe a structure, with a larger basis set giving a more accurate depiction.[5] When we run an optimisation we are aiming to identify a minimum point on the potential energy surface for the molecule in question. If this calculation were run using a better, larger basis set the energy output would be quite different. This can be shown by comparing the energy output for an optimised BH3 molecule calculated using 3-21G and 6-31G basis sets: -26.4622638 and -26.61532364 a.u respectively – a difference of 401.86 kJ/mol! It is clear from this that results obtained using different basis sets will differ greatly and should not be directly compared. Furthermore, these energies are the basis of frequency analysis calculations, with the second derivative of stationary point energies being converted to coordinates and vibrational modes. Therefore, in order to have comparable optimisation and frequency analysis outputs, the method and basis set must be kept consistent.[5]

4)What is the purpose of carrying out a frequency analysis?

Frequency analysis computes the second derivative of stationary point energies found via optimisation calculations, and allows us to see if a minimum has been found. This second derivative calculation is crucial as the first derivative of both a maximum and minimum point on a potential energy surface are equal to zero. If we find the analysis file contains low frequencies with negative values a minima has not been identified, and re-optimisation is required.[5]

5)What do the "Low frequencies" represent?

For non-linear molecules, the vibrational modes are given by 3N-6 where N is the number of atoms in the molecule. The low frequencies are the ‘-6’ part of this equation and represent the molecules centre of mass motion; if these are not within ± 15 cm-1 of one another it is best to reoptimise the structure and run a second frequency analysis. For a good optimisation we would expect these low frequencies to have values close to zero.[3]

Molecular Orbitals of BH3-

A population analysis was conducted in order to generate the real molecular orbitals of BH3 and these have been compared with those predicted via the Linear Combination of Atomic Orbitals method.

| Method | Basis Set |

|---|---|

| B3LYP | 3-21G |

Molecular Orbital Analysis File can be accessed via:DOI:10042/90778

Analysis of results-

Are there any significant differences between the real and LCAO MOs?

In general there is good agreement between the real and LCAO generated molecular orbitals in terms of their phase patterns and the presence of nodes. The main difference comes in the form of the real molecular orbitals beings far more diffuse than the localised LCAO versions. For example, the a1’ LCAO generated molecular orbital consists of three separate s-type orbitals located on the hydrogen atoms, and a smaller, same-phase s-type orbital on the central boron atom; the real molecular orbital however is one large, diffuse orbital encompassing the whole molecule. Whilst the LCAO version is accurate in its prediction of a bonding, in-phase interaction of orbitals, it predicts a larger contribution from the hydrogen ligands due to the molecular orbital being closer in energy to the ligand fragment atomic orbital, which is not apparent from the real image. For the 1e’ molecular orbitals there is again some disparity between the real and LCAO generated atomic orbitals; whilst the latter predicts sharp nodes through the central atom (vertically and horizontally) these are less well defined in the computed molecular orbital images. The combination of two s-type orbitals and a py orbital via the LCAO method predicts a symmetrical phase distribution about the x-axis, however, the real molecular orbital is less symmetrical, with one lobe being larger and of a different shape to the other. Generally the LCAO method has predicted molecular orbitals of the correct phase distribution and overall bonding/anti-bonding character and is therefore good for initial analysis of a system or prediction of properties, however, the real molecular orbitals are more accurate in terms of the orbitals being more diffuse and less perfect than predicted. The LCAO method is a useful tool as it does not require the use of specialised programs or complex calculations and gives a fair approximation of the real molecular orbitals.

NH3

The NH3 molecule has been optimised and a frequency analysis carried out to confirm the minimum energy structure. A population analysis and finally NBO analysis were also performed. Alongside the optimised structure and vibrational spectrum, the separation of charge found via the Natural Bond Orbital analysis is displayed below.

| Method | Basis Set | Calculation Type |

|---|---|---|

| B3LYP | 6-31G | OPT |

Optimisation Log File can be accessed: here

| Summary Data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000006 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000004 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000012 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000008 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-9.841964D-11

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

|

|

Frequency Analysis -

| Method | Basis Set | Calculation Type |

|---|---|---|

| B3LYP | 6-31G(d,p) | FREQ |

Frequency Log File can be accessed:here

| Summary Data | Low Modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -0.0137 -0.0025 0.0013 7.0781 8.0927 8.0932 Low frequencies --- 1089.3840 1693.9368 1693.9368 |

| Wavenumber (cm-1) | Intensity | IR active? | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1694 | 14 | SLIGHTLY | BEND |

| 1694 | 14 | SLIGHTLY | BEND |

| 1089 | 145 | YES | BEND |

| 3461 | 1 | VERY SLIGHTLY | STRETCH |

| 3590 | 0 | NO | STRETCH |

| 3590 | 0 | NO | STRETCH |

MO Analysis -

| Method | Basis Set | Type |

|---|---|---|

| B3LYP | 6-31G(d,p) | Energy |

Molecular Orbital Analysis File can be accessed via:DOI:10042/92838

NBO Analysis -

| Charge Distribution | Colour Range |

|---|---|

|

|

| Image | Nitrogen Charge | Hydrogen Charge |

|---|---|---|

|

-1.135 | 0.375 |

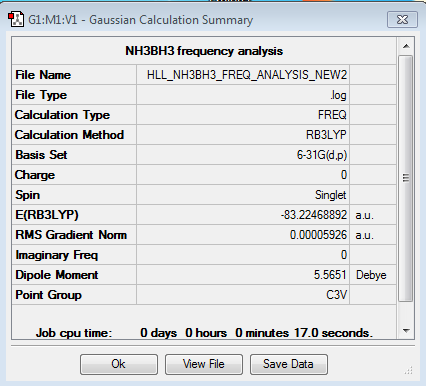

NH3BH3 -

The NH3BH3 molecule was optimised and the frequency analysis carried out on. The calculated energy of the molecule has been used alongside results for the NH3 and BH3 molecules to calculate the association energy of the molecule, and its stability relative to them has been discussed.

Optimisation -

| Method | Basis Set | Calculation Type |

|---|---|---|

| B3LYP | 6-31G | OPT |

Optimisation Log File can be accessed: here

| Summary Data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000121 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000057 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000507 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000295 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-1.613110D-07

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

|

|

Frequency Analysis -

| Method | Basis Set | Calculation Type |

|---|---|---|

| B3LYP | 6-31G(d,p) | FREQ |

Frequency Log File 1 can be accessed:here

| Summary Data | Low Modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -0.0254 -0.0033 -0.0010 17.0394 17.0419 36.9081 Low frequencies --- 265.7475 632.2122 639.3355 |

This first frequency analysis gave low frequencies not within +/- 15cm-1 so a second optimisation was performed.

The second optimisation Log File can be accessed: here

| Summary Data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000002 0.000015 YES

RMS Force 0.000001 0.000010 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000009 0.000060 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000002 0.000040 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-2.727594D-11

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

|

|

Frequency Log File 2 (Frequency Analysis with re-optimised molecule) can be accessed:here

| Summary Data | Low Modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -5.3923 -0.3765 -0.0578 -0.0014 0.9370 1.0527 Low frequencies --- 263.2935 632.9557 638.4557 |

| Wavenumber (cm-1) | Intensity | IR active? | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 263 | 0 | NO | BEND |

| 633 | 14 | SLIGHTLY | STRETCH |

| 638 | 4 | VERY SLIGHTLY | BEND |

| 638 | 4 | VERY SLIGHTLY | BEND |

| 1069 | 41 | YES | BEND |

| 1069 | 41 | YES | BEND |

| 1196 | 109 | YES | BEND |

| 1204 | 3 | VERY SLIGHTLY | BEND |

| 1204 | 3 | VERY SLIGHTLY | BEND |

| 1329 | 114 | YES | BEND |

| 1676 | 28 | YES | BEND |

| 1676 | 28 | YES | BEND |

| 2472 | 67 | YES | STRETCH |

| 2532 | 231 | YES | STRETCH |

| 2532 | 231 | YES | STRETCH |

| 3464 | 3 | VERY SLIGHTLY | STRETCH |

| 3581 | 28 | YES | STRETCH |

| 3581 | 28 | YES | STRETCH |

Energy of the bond -

| E(NH3) a.u | E(BH3) a.u | E(NH3BH3) a.u |

|---|---|---|

| -56.5577687 | -26.6153236 | -83.2246890 |

Calculation:

ΔE = E(NH3BH3) - [E(NH3)+ E(BH3)]

ΔE = -83.2246890 - [(-56.5577687) + (-26.6153236)]

ΔE = -0.0515967 a.u

ΔE = -135.48 kJmol-1

Analysis of Results-

Is the association of NH3 and BH3 to form a B-N bond within NH3BH3 weak, medium or strong?

The bond energy calculation gave a value of -135.48 kJmol-1; this is much lower than typical first order bond enthalpies such as N-C (305 kJmol-1) and C-H (412 kJmol-1)[1] and so would be classed as a weak bond. The bonding interaction is a dative bond with two electrons from nitrogen being donated to the vacant p orbital of the electron deficient boron atom and therefore acts to stabilise the lewis acidic boron.

Mini Project- Lewis Acids and Bases:

AlCl2Br -

The AlCl2Br monomer has been optimised in order to use its energy in calculations for dimer dissociation later on. The optimisation calculations of this molecule and the dimers have been carried out at the same level so as to allow direct comparison of results.

| Method | Basis Set | Calculation Type |

|---|---|---|

| B3LYP | GEN (6-31G(d,p) and LanL2DZ) | OPT |

Optimisation Log File can be accessed via:DOI:10042/101601

| Summary Data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000000 0.000015 YES

RMS Force 0.000000 0.000010 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000000 0.000060 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000000 0.000040 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-2.292750D-16

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

|

|

AlCl4Br2 -

4 different isomers of AlCl4Br2 were created using Gaussview. Each was optimised as shown; in every case this first optimisation did not converge and so reoptimisations were performed. The reoptimisations all converged, and these results are displayed below. It is suggested that the initial molecule was highly deformed, with unrealistic bond lengths and so the initial optimisation could not cause conversion. The first optimisation yielded a more realistic molecular geometry and so reoptimisation was successful in all cases.

AlCl4Br2 Isomer 1 -

| Method | Basis Set | Calculation Type |

|---|---|---|

| B3LYP | Gen (6-31G(d,p) and LanL2DZ) | OPT |

Optimisation Log File 1 (did not converge) can be accessed:here

Optimisation Log File 2 can be accessed via:DOI:10042/101526

| Summary Data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000001 0.000015 YES

RMS Force 0.000000 0.000010 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000018 0.000060 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000006 0.000040 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-1.133351D-11

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

|

|

AlCl4Br2 Isomer 2 -

| Method | Basis Set | Calculation Type |

|---|---|---|

| B3LYP | Gen (6-31G(d,p) and LanL2DZ) | OPT |

Optimisation Log File 1 (did not converge) can be accessed:here

Optimisation Log File can be accessed via:DOI:10042/101624

| Summary Data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000001 0.000015 YES

RMS Force 0.000000 0.000010 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000013 0.000060 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000004 0.000040 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-1.119329D-11

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

|

|

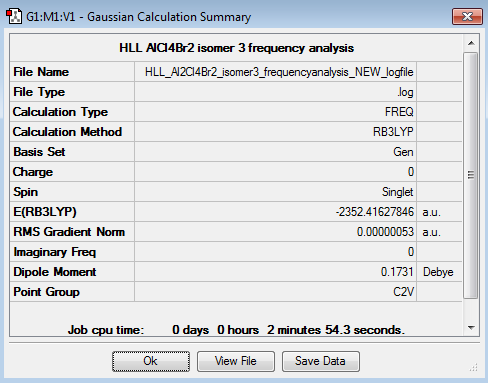

AlCl4Br2 Isomer 3 -

| Method | Basis Set | Calculation Type |

|---|---|---|

| B3LYP | Gen (6-31G(d,p) and LanL2DZ) | OPT |

Optimisation Log File 1 (did not converge) can be accessed:here

Optimisation Log File can be accessed via:DOI:10042/101681

| Summary Data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000001 0.000015 YES

RMS Force 0.000000 0.000010 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000023 0.000060 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000008 0.000040 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-1.397236D-11

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

|

|

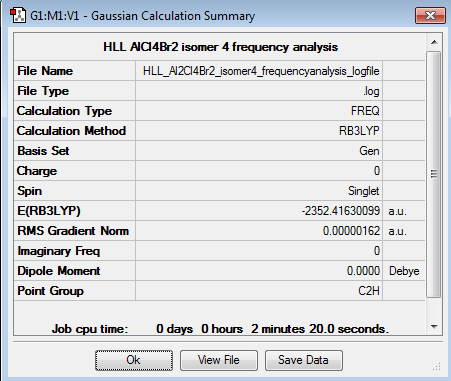

AlCl4Br2 Isomer 4 -

| Method | Basis Set | Calculation Type |

|---|---|---|

| B3LYP | Gen (6-31G(d,p) and LanL2DZ) | OPT |

Optimisation Log File 1 (did not converge) can be accessed:here

Optimisation Log File can be accessed via:DOI:10042/101766

| Summary Data | Convergence | Jmol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000001 0.000015 YES

RMS Force 0.000000 0.000010 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000010 0.000060 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000004 0.000040 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-3.925021D-12

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

|

|

Energy Calculations and discussion -

| Isomer 1 | Isomer 2 | Isomer 3 | Isomer 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy (a.u Hartrees) | -2352.4063255 | -2352.4111073 | -2352.4162785 | -2352.4162998 |

From this it is apparent that Isomer 4 is the lowest energy conformer as it has the most negative energy. The energy of each isomer has been compared to that of Isomer 4 to give the relative energies of each isomer in kJmol-1 with the values tabulated below:

| Isomer 1 | Isomer 2 | Isomer 3 | Isomer 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative energy(kJmol-1) | + 26.19 | + 13.63 | + 0.06 | - |

Discussion:

The Aluminium centres are 4 coordinate, however the bond angles observed (approximately 90 to 92o in the bridge and 121 to 122o between the terminal halogen ligands) are far from the anticipated 109.5o.[1] This is due to the bridging bonds being 3 centre-4 electron bonds and thus not being typical bonds casuing the structure to become slightly deformed. The AlCl2Br monomer units are electron deficient lewis acidic species much like the EX3 molecules studied above, and the dimeric form is preferred due to the sigma donation of the bridging halogen lone pairs into aluminium’s vacant p orbital which stabilses the structure. This leads to the bridged dimer geometry whereby the bridging ligands are donating more than one electron pair to more than one metal atom.[1] There is a marked difference in the energies of the dimer conformers which feature bromine as either one of, or both of these bridging ligands, compared with the conformers in which both bridging ligands are chlorine atoms. Both bromine and chlorine have a lone pair of electrons available for donation and so can accommodate the dimeric structure, therefore the energy differences are suspected to be related to size and consequently, orbital overlap efficiency. It is expected that due to the 3 centre-4 electron nature of the bridging bonds that these will be longer than the bonds between the terminal ligands and aluminium atoms. The electrons in the bridge are shared across more atoms and so the electron density in the bridge would be more spread out resulting in weaker and therefore longer bonds. The bond length data supports this conclusion, with the lowest energy conformer having bridging bonds of length 2.30 Å and terminal bonds of length 2.09 Å. The small bridging angles are fairly restrictive, and in order to maintain a good overlap with atomic orbitals from both aluminium atoms, a smaller bridging ligand is desired [6]; in this case chlorine would be the bridging ligand of choice. This is supported by the relative energies of each isomer, with the highest energy conformer having zero chlorine bridging atoms, and the lowest energy conformer having both bridging atoms as chlorine. Contrary to this, from an electronegativity perspective, it would be expected that the more electronegative atom, in this case chlorine, would hold more tightly onto its lone pair of electrons rendering them less available for donation and causing it to be a poorer bridging ligand. Since the relative electronegativities of bromine and chlorine are fairly similar (Pauling electronegativities of 2.96 and 3.16 respectively)[1], it is concluded that size and orbital overlap play a larger part in the overall stability of the dimer conformers. The lone pair of electrons possessed by the bridging halide must be donated into the vacant sp3 hybridized orbitals of the aluminium atoms [6], and as previously discussed for the EX3 molecules, bonding interactions are greatest when the atomic orbitals involved are of a similar size; this leads to the conclusion that chlorine bridges would give the best orbital overlap and so strongest interaction due to its valence electrons being in a 3p orbital, rather than the more diffuse 4p orbital for bromine atoms. From this it is concluded that bridging chlorine ligands lead to a stonger bridging interaction, and so terminal bromine ligands are found in the most stable conformers, those of lowest energy. Furthermore, the slight difference in stability between isomers 3 and 4 is suggested to be from steric issues. In isomer 4, the trans arrangement of the bulky bromine atoms causes them to be as far apart as possible and so minimises their steric repulsion; this slight reduction in steric clashing is therefore attributed to the energy lowering of 0.06 kJmol-1 between isomers 3 and 4.

It is then possible to calculate the dissociation energy for Isomer 4 dissociating into two molecules of AlCl2Br; the calculations are shown below:

| Isomer 4 | AlCl2Br monomer | |

|---|---|---|

| Energy (a.u Hartrees) | -2352.4162998 | -1176.1901404 |

Calculation:

ΔE = [E(AlCl2Br monomer) x 2] - E(Al2Cl4Br2 isomer 4)

ΔE = [2(-1176.1901404)] - (-2352.4162998)

ΔE = 0.036019 a.u

ΔE = 94.57 kJmol-1

Discussion and literature comparison:

The dimer has a more negative energy than two AlCl3 monomer units, and it therefore stabilised relative to them. The stabilisation is due to the donation of electrons through the dimer bridge to relieve the electron deficiency of the aluminium atoms. The dissociation energy of a similar group 13 dimer, Al2Cl6 is found to be 170 kJmol-1, [7] this is of a similar magnitude to the energy calculated, and also supports the finding that the dimeric form is more stable than the isolated monomers.

AlCl4Br2 Frequency Analysis and Comparisons -

In each case, the optimised structure did not specify the correct symmetry for the molecule and so this was determined based up the symmetry elements present,[1] and constrained before the frequency analysis was performed.

| Isomer 1 | Isomer 2 | Isomer 3 | Isomer 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry Elements | E, 3 C2 axes, 3 mirror planes, centre of inversion | E | E, 1 C2 axes, 2 mirror planes | E, 1 C2 axes, 1 mirror plane, centre of inversion |

| Point Group | D2h | C1 | C2v | C2h |

AlCl4Br2 Isomer 1 Frequency Analysis -

| Method | Basis Set | Calculation Type |

|---|---|---|

| B3LYP | GEN (6-31G9d,p) and LanL2DZ) | FREQ |

Frequency Log File can be accessed via:DOI:10042/104231

| Summary Data | Low Modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -0.8186 -0.0020 0.0023 0.0034 1.3093 1.3836 Low frequencies --- 16.0729 63.6239 86.1121 |

| Wavenumber (cm-1) | Intensity | IR active? | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16 | 0 | NO | BEND |

| 64 | 0 | NO | BEND |

| 86 | 0 | NO | BEND |

| 87 | 0 | NO | BEND |

| 108 | 5 | VERY SLIGHTLY | BEND |

| 111 | 0 | NO | BEND |

| 126 | 8 | VERY SLIGHTLY | BEND |

| 135 | 0 | NO | BEND |

| 138 | 7 | VERY SLIGHTLY | BEND |

| 163 | 0 | NO | BEND |

| 197 | 0 | NO | STRETCH |

| 241 | 100 | YES | STRETCH |

| 247 | 0 | NO | STRETCH |

| 341 | 161 | YES | STRETCH |

| 468 | 348 | YES | STRETCH |

| 494 | 0 | NO | STRETCH |

| 609 | 0 | NO | STRETCH |

| 617 | 332 | YES | STRETCH |

AlCl4Br2 Isomer 2 Frequency Analysis -

| Method | Basis Set | Calculation Type |

|---|---|---|

| B3LYP | GEN (6-31G9d,p) and LanL2DZ) | FREQ |

Frequency Log File can be accessed via:DOI:10042/104379

| Summary Data | Low Modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -0.1817 0.0020 0.0020 0.0024 1.1023 1.8100 Low frequencies --- 16.9430 55.9194 80.0645 |

| Wavenumber (cm-1) | Intensity | IR active? | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 17 | 0 | NO | BEND |

| 56 | 0 | NO | BEND |

| 80 | 0 | NO | BEND |

| 92 | 1 | VERY SLIGHTLY | BEND |

| 107 | 0 | NO | BEND |

| 110 | 5 | VERY SLIGHTLY | BEND |

| 121 | 8 | VERY SLIGHTLY | BEND |

| 149 | 5 | VERY SLIGHTLY | BEND |

| 154 | 6 | VERY SLIGHTLY | BEND |

| 186 | 1 | VERY SLIGHTLY | BEND |

| 211 | 21 | SLIGHTLY | STRETCH |

| 257 | 10 | SLIGHTLY | STRETCH |

| 289 | 48 | YES | STRETCH |

| 384 | 153 | YES | STRETCH |

| 424 | 274 | YES | STRETCH |

| 493 | 107 | YES | STRETCH |

| 575 | 122 | YES | STRETCH |

| 615 | 197 | YES | STRETCH |

AlCl4Br2 Isomer 3 Frequency Analysis -

| Method | Basis Set | Calculation Type |

|---|---|---|

| B3LYP | GEN (6-31G9d,p) and LanL2DZ) | FREQ |

Frequency Log File can be accessed via:DOI:10042/104421

| Summary Data | Low Modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -1.3327 -0.7438 -0.0029 -0.0020 -0.0014 2.2272 Low frequencies --- 17.4970 51.1455 78.5263 |

| Wavenumber (cm-1) | Intensity | IR active? | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18 | 0 | NO | BEND |

| 51 | 0 | NO | BEND |

| 79 | 0 | NO | BEND |

| 99 | 0 | NO | BEND |

| 103 | 3 | VERY SLIGHTLY | BEND |

| 121 | 13 | SLIGHTLY | BEND |

| 123 | 6 | VERY SLIGHTLY | BEND |

| 157 | 0 | NO | BEND |

| 158 | 5 | VERY SLIGHTLY | BEND |

| 194 | 2 | VERY SLIGHTLY | BEND |

| 263 | 0 | NO | STRETCH |

| 279 | 26 | SLIGHTLY | STRETCH |

| 308 | 2 | VERY SLIGHTLY | STRETCH |

| 413 | 149 | YES | STRETCH |

| 420 | 410 | YES | STRETCH |

| 461 | 35 | YES | STRETCH |

| 571 | 33 | YES | STRETCH |

| 583 | 277 | YES | STRETCH |

AlCl4Br2 Isomer 4 Frequency Analysis -

| Method | Basis Set | Calculation Type |

|---|---|---|

| B3LYP | GEN (6-31G9d,p) and LanL2DZ) | FREQ |

Frequency Log File can be accessed via:DOI:10042/104405

| Summary Data | Low Modes |

|---|---|

|

Low frequencies --- -0.8053 -0.7614 -0.0038 -0.0032 -0.0023 2.1392 Low frequencies --- 18.3046 49.2153 72.9030 |

| Wavenumber (cm-1) | Intensity | IR active? | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18 | 0 | NO | BEND |

| 49 | 0 | NO | BEND |

| 73 | 0 | NO | BEND |

| 105 | 0 | NO | BEND |

| 109 | 0 | NO | BEND |

| 117 | 9 | VERY SLIGHTLY | BEND |

| 120 | 13 | SLIGHTLY | BEND |

| 157 | 0 | NO | BEND |

| 159 | 6 | VERY SLIGHTLY | BEND |

| 192 | 0 | NO | BEND |

| 263 | 0 | NO | STRETCH |

| 280 | 29 | SLIGHTLY | STRETCH |

| 308 | 0 | NO | BEND |

| 413 | 149 | YES | STRETCH |

| 421 | 438 | YES | STRETCH |

| 459 | 0 | NO | STRETCH |

| 575 | 0 | NO | STRETCH |

| 580 | 316 | YES | STRETCH |

Discussion:

Molecules possess 3N degrees of freedom, corresponding to displacements along the x, y and z axes; three of these are taken up by translation along each axis, and a further three by rotation about each axis, leaving the molecule with 3N-6 possible vibrational modes.[1] For all four isomers the (3N – 6) calculation yields 18 vibrational modes, however, many of these are IR inactive due to causing no dipole moment change and so do not feature in the spectra presented. Unlike the EX3 species, non of the vibrational modes appear to be degenerate, however, the presence of weak absorption bands in close proximity have caused broadening of the peaks in some cases. Furthermore, for isomers 3 and 4, the high intensity peaks at around 420 cm-1 are actually due to two intense, yet close in frequency vibrational modes, which can give the impression of missing peaks. Isomer two has the most IR active vibrations at 12; this is believed to be due to its lack of symmetry. The point group for isomer 2 was determined to be C1,[1] with such an unsymmetrical molecule, it is more likely that an angle deformation or bond stretches would result in a change in dipole moment for the molecule and so a greater number of peaks on its spectrum. Comparison with the highly symmetric isomer 1 which only has 7 active vibrational modes highlights how stretching a symmetrical molecule in particular can lead to no change in dipole and therefore no IR peak for the displacement. Symmetric stretches leave the dipole moment of the more symmetrical isomers unchanged and so many of the higher frequency, stretching modes that are present in the spectrum for isomer 2 are missing in the spectra of isomers 1 and 4. Group theory could also be used to predict the number of IR and Raman active vibrational modes[1] from the point groups of molecules, and is something I would have liked to use as a way of verifying the resulting spectra with theory if given more time. From the discussion regarding the EX3 vibrational spectra, it was concluded that longer, weaker bonds would have a lower spring constant k, and so vibrate at lower frequencies; it is therefore predicted that the bridging bonds would have stretching frequencies below that of the terminal bond stretches. In isomer 1 only bridging bromine atom is present and the molecule has high symmetry, for this reason we do not see the symmetric stretches at 197and 247 cm-1. The IR active stretches involving these bridging bonds are the asymmetric stretches at 241 and 341 cm-1. Whilst we have no terminal bromine atoms, we can indirectly compare the stretching frequency of the bridging bonds with those of the terminal chlorine ligand bonds; these stretches are the highest recorded stretches at 609 and 617 cm-1, with the latter being the active, asymmetric stretch. As anticipated, these vibrational modes have much higher frequencies than the bridging stretches due to increased bond strength and so stiffer bonds. Isomer 2 allows comparison of bridging and terminal bromine stretches, with the symmetric stretches also being IR active due to the unsymmetrical nature of the bridging and terminus regions. The bridging stretches mentioned for isomer 1 now occur at 211, 257, 289 and 384 cm-1 respectively. Each vibrational frequency has been increased slightly, but is still far below the frequency for the terminal stretch: 547cm-1; as predicted the stronger terminal bromine bonds have higher vibrational frequencies than the bridging stretches do. It is also noted that during these terminal bond stretches the bromine atom moves negligibly compared to the chlorine atoms; this is due to bromine being a much heavier atom than chlorine. Furthermore, the corresponding stretch for the Cl-Al-Cl side of the dimer occurs at an even higher frequency of 614 cm-1; this can again be traced back to the vibrational frequency equation[1] whereby the lower mass of a chlorine atom compared to a bromine atom reduces the μ value and so increases the frequency. In isomers 3 and 4 there are no bridging bromine atoms, and the terminal bond stretches, both symmetric and antisymmetric, occur at comparable wavelengths near to 600cm-1. These high frequencies are expected and correlate well with the terminal stretch reported for isomer 2. The only difference is that both stretches are IR active for isomer 3 whereas the symmetry of isomer 4 renders the asymmetric stretch IR inactive. In conclusion, as predicted, the weaker bridging bonds caused vibrational modes to occur at lower frequencies, due to lower bond stiffness, and the stretches of terminal bromine bonds resulted in vibrational modes at lower frequencies than those of the corresponding terminal chlorine bonds due to a higher reduced mass of the system.

Molecular Orbital calculation and discussion -

| Method | Basis Set | Type |

|---|---|---|

| B3LYP | GEN (6-31G(d,p)and LanL2DZ) | Energy |

Molecular Orbital Analysis File can be accessed via:DOI:10042/109849

The molecular orbital analysis gave 54 populated molecular orbitals, with orbitals 31 to 54 being non-core, diffuse orbitals. Each of these orbitals was visualised in Gaussview, and five are presented below with a discussion of their interactions.

| MO 1 | MO 2 | MO 3 | MO 4 | MO 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orbital Number | 31 | 32 | 40 | 53 | 54 |

| Orbital energy | -0.91063 | -0.88775 | -0.43349 | -0.32036 | -0.31845 |

| Image of interactions |  |

|

|

|

|

MO 1:

The lowest non-core molecular orbital is fairly simple; it is a completely bonding interaction as only one phase is present, and the main proportion of the orbital is spread across the bridging region of the dimer. The core orbitals were localised on specific atoms, but this molecular orbital shows a strong through space bonding interaction across the entire bridge (black arrow). This interaction is believed to be due to overlapping orbitals of the same phase on the chlorine atoms and therefore possesses no nodes. There are two further small orbital contributions on the terminal chlorine atoms, these have medium through space bonding interactions with the bridge (blue arrows) and weak through space bonding interactions with each other (red arrow). As this molecular orbital is so low in energy, only the most electronegative atom, chlorine, has any orbital contribution and so this does not describe the bonding interaction between the aluminium and terminal bromine atoms.

MO 2:

This molecular orbital shows strong through space out-of-phase interaction (black arrow) in the bridging region with a clear nodal plane running through the centre of the lobes (blue line). Again due to the low energy of the molecular orbital in question, only the bridging chlorine atoms are involved in the interaction, with the other atomic orbital fragments being too high in energy to participate. The two orbital lobes are very symmetrical suggesting an equal sharing of electron density between the bridging chlorine atoms. This orbital has a strong anti-bonding character due to the out-of-phase interaction and presence of a nodal plane in the internuclear region, indicating that no electron density is to be found in this region.

MO 3:

This molecular orbital is also overall anti-bonding in character and features a nodal plane alongside 5 nodes on atomic centres (blue lines). Now that we are looking at a molecular orbital of higher energy, the molecular orbital lobes show electron density in both the bridging and terminal regions of the dimer, with the nodes on the terminal atoms centres being less important than the nodal plane through the bridge. Strong through bond, out-of-phase interactions between the lobes on terminal atoms and the bridging region are shown in black, as is the strong through bond out-of phase interaction in the bridging region itself. Weak out-of-phase interactions through space are also identified between terminal bromine and chlorine atoms with red arrows, and very weak through space bonding interactions between terminal atoms of the same kind are shown via green arrows. Furthermore, weak through space in-phase interactions between the terminal atoms and bridging region are shown in yellow. Although there are some bonding interactions, the molecular orbital is considered to be overall anti-bonding as the out-of-phase interactions are stronger. It is noted that the terminal chlorine atoms have slightly larger lobes than the terminal bromine atoms, and this is suggested to be due to the molecular orbital being a little closer in energy to the chlorine atomic orbital fragments.

MO 4:

The first thing that is noted about this molecular orbital is the lack of lobes and therefore electron density in the bridging region, and so it only describes the bonding interactions within the terminal fragments. In contrast to the previous molecular orbitals, the main orbital contribution now lies on the bromine atoms, not the chlorine atoms suggesting that it’s energy is closer to that of the terminal bromine fragments. 4 nodes localised on atomic centres have been identified alongside two orthogonal nodal planes in the internuclear region; all 6 have been highlighted in blue. There are weak (green) and very weak (yellow) through space bonding interactions present between the terminal bromine and chlorine ligands, however due to the delocalised ‘p’ orbital type lobes, these are matched with weak (black) through space out-of-phase, anti-bonding interactions. Due to the presence of two internuclear nodal planes suggesting no bonding interactions within the bridging region, it is concluded that this is a strongly anti-bonding molecular orbital.

MO 5:

The highest occupied molecular orbital is not too dissimilar from molecular orbital 4, however, it now features lobes on the bridging chlorine atoms. This is the most highly anti-bonding molecular orbital, with nodes (blue lines) on six atom centres, out-of-phase interactions between both terminal and bridging regions, and no orbital contribution on the aluminium atoms. Strong in-phase interactions through space are observed between the bridging chlorines (green), and weak through space anti-bonding interactions between their out-of-phase lobes (red), this out-of-phase interaction is weaker due to the orbital lobes being at an angle to one another. Please note that in order to avoid over complicating the image, only one of each type of interaction has been identified with an arrow. We can also identify weak through space in-phase interactions between the terminal ligand and the bridging chloride atoms (yellow), again these are determined to be weak due to the orbital lobes being angled. Finally there are strong (black), weak (pink) and very weak (light blue) out-of phase through space interactions between the terminal halogen atoms. Overall, there are more out-of-phase interactions, and so this molecular orbital is strongly anti-bonding in character.

References:

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 Shriver, Atkins, Inorganic Chemistry, Oxford University, 5th Edition,2010, pp 22, 29, 34-60, 63-72, 83-107, 131-134, 179-196, 230-233, 325-328

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Clayden, Greeves, Warren, Organic Chemistry, Oxford University, 2nd Edition,2001, pp 63-72 and 85-104

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 The Hunt Research Group Website, accessed online via: http://www.huntresearchgroup.org.uk/teaching Accessed during November 2014

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Atkins, De Paula, Atkins' Physical Chemistry, Oxford University, 9th Edition,2010 pp 462-465 and 471-474

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 M Bearpark, Quantum Mechanics 3 Lecture course, Imperial College London, October 2014

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 G. Raj, Advanced Inorganic Chemistry Vollume II, Krishna Prakashan Media,pp 173-176, Accessed online via Google Books on 19.11.2014.

- ↑ M, Tranquille, M. Fauassier, J. Chem. Sic., Faraday Trans. 2, 1980, 76, pp26-41