Rep:Mod:FordpageDA

Transition States of a selection of pericyclic reactions

In this article, computational data on a number of reactions is presented, and analysis of such is presented where applicable.

Introduction

Pericyclic reactions are of fundamental importance to chemistry, capable of quickly forming complex architectures of a carbon skeleton. However, problems can arise with regio- and chemo-selectivity of these reactions, both of which shall be demonstrated in this article. Luckily, these issues can be countered by consideration of the kinetics vs thermodynamics of such reactions; in practice it is often found that the Endo product of a Diels Alder dominates under kinetic conditions, but in order to understand this phenomenon the transition state must be considered. The usefulness of computational chemistry lies in its ability to image these fleeting events, near impossible experimentally, as well as provide deeper understanding of reactions by orbital and thermodynamic analyses.

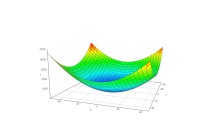

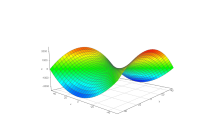

In computational chemistry, the program explores the potential energy surface-the PES for a reaction. In its most fundamental form this exists in highly complex space with 3(N-1) dimensions, N representing the number of atoms within a molecule, but in practice can sometimes be simplified to only consider atoms the interact strongly in the chemistry being studied. The energy at each point is calculated by solving the schrödinger equation given a set of nuclear coordinates, but different sets of orbitals, known as basis sets, can be used to give varying accuracy levels compared to reality. In any case, there are two points of special interest on the surface, these being the minimum and saddle points, which represent the physical phenomena of average atomic configuration and transition state respectively.

Mathematically, a minimum is defined as a point where all first derivatives are zero and all second derivatives are positive. A saddle point occurs when all first derivatives are again zero, and all second derivatives but one are positive. Chemically, a transition point is the highest point on the lowest energy path between two wells; these defining the rest states of the reactants and products. It follows from this that a test for the transition state is that at this point there exists exactly one vibration with negative frequency; this corresponds to motion along the reaction coordinate along which the potential energy is reduced. The negative k value in this coordinate produces an imaginary vibration, which is unphysical. Furthermore, the definition of a single non-negative second derivative means that if there is more than one negative vibration then the wrong transition state has been found.

Nf710 (talk) 11:12, 12 January 2018 (UTC) Its 3N-6 degrees of freedom. This is well written however. You can get the force constants s the eigen values of the hessian matrix which has dimension (3N-6)^2

In this article, two levels of basis set are used: PM6 is used in the cycloaddition of ethene and butadiene and the reaction of xylylene and sulfur dioxide, but the higher quality DFT B3LYP 631G(p) set is used for the cyclohexadiene and 1,3-dioxole investigation, as this method gives more reliable thermochemical data. PM6 is a faster and less intensive method that uses experimental data to reduce the time required to diaganolise the matrix generated as part of the energy calculation, and provides a good enough approximation of reality so can be used for a rough estimate of transition state geometry, which can be further refined by the use of a higher level method. The B3LYP 631G(p) set is a much more comprehensive basis set and method, not only solving the hamiltonians exhaustively without reliance on data, but allowing for orbitals to deform slightly in going from reactant to product.

Nf710 (talk) 11:12, 12 January 2018 (UTC) Nice you have shown some understanding of the Quantum chemical methods here. Some equations would have backed up your discussion

The cycloaddition of ethene and butadiene

Orbitals and the transition state

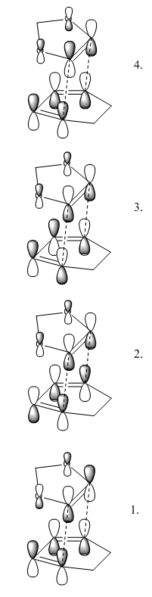

This first reaction is in fact mainly hypothetical. Ethene and butadiene are poor reagents for cycloaddition chemistry as ethene is not particularly electron poor, nor butadiene especially electron rich! This results in poor orbital overlap and unfavourable kinetics. However, it is an ideal model reaction, as it is the simplest possible Diels-Alder 6-ring formation, the product being cyclohexene. The table below displays the molecular orbital interaction diagram for the reaction, along with interactive images of the orbitals concerned. The labels S and AS represent symmetric and antisymmetric molecular orbitals, and the numbered transition state orbitals are presented on red background to the side.

|

4. | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3. | |||||||||

| 2. | |||||||||

| 1. |

During the reaction, the MOs shown in the diagram interact to form new MOs for the product. What this diagram illustrates is that both symmetric-symmetric and antisymmetric-antisymmetric interactions result in good orbital overlap, but an attempt to interact symmetric-antisymmetric fails as the net orbital overlap will be zero at the angle of attack. In conclusion, same-symmetry orbitals may interact so long as the overall interaction results in a lowering of the overall energy of the molecule.

(Fv611 (talk) Your MO combinations are correct, but you didn't consider the relative energies of the MOs when you drew your diagram. While it is true that in the product the TS HOMO and HOMO-1 will be the lowest energy orbitals, this is not true at the TS, where the dienophile HOMO has the lowest energy. Similarly, at the TS, the ethene's LUMO has the highest energy. Additionally, you should have added symmetry labels for your TS MOs, and you could have expanded your discussion on the symmetry and orbital overlap requirements.)

The reaction coordinate

The reaction coordinate can be understood as a measure of the progression of a reaction, but in a reaction with many atoms present, such as this one, an exact definition is not as simple as just the bond length between two atoms, as could probably be used for a binuclear reaction. As well as the immediate vicinity of the bond being formed, changes in hybridisation and bond order throughout the structure can play a role in determining the extent of reaction, and indeed programs may use a technique where a linear approximation of the reaction coordinate is followed as a starting point to locating the exact transition state, so long as the bond lengths in the reactants and product are known. The carbon-carbon bond lengths of reactants and products are tabulated below, alongside the vibrational mode that takes one to the other.

Overall, this data illustrates the progression of the reaction very well. The products initially start with bond lengths very much in line with those expected for carbon sp3 and sp2 hybridised bonds (1.54 Å and 1.34 Å respectively), except in the 4-5 bond length, which is shortened due to the influence of the conjugated system. In the transition state, all double bonds have increased in length by approximately 0.05 Å, corresponding to the shift in electron density away from the pi bonds and into the new sigma bonds about to be formed. At 2.11 Å the newly forming bonds are still a distance apart, but significantly less than twice the Van de Waals radius of carbon (1.70 Å). This is a clear demonstration of a concerted attack, as the trajectory is symmetrical and both bond lengths are equal. The bond between carbons 4 and 5 decreases in length as it gains pi character. Finally, in the product the bond lengths are once again very standard. The newly formed sigma bonds are equal in length and at 1.54 Å are exactly as expected for a carbon-carbon single bond.

LOGS:

The cycloaddition of cyclohexadiene and 1,3-dioxole

Orbitals and the transition state

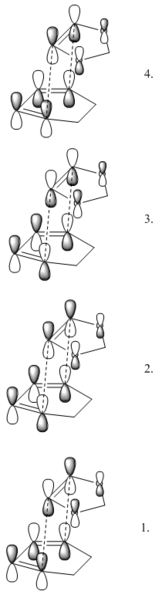

Another example of a cycloaddition, this time with more complex reactants. The same principles as before apply, but the MOs are a little more complicated. Of note are the interactions in the TS orbitals 1. and 2., as labelled here. A secondary orbital interaction between the oxygen based P orbitals and the pi system of the diene lowers the energy of these orbitals for the endo attack vs exo, and thus leads to a kinetically favourable endo transition state. Another important observation is the relative energies of the diene and dienophile orbitals. compared to the previous case, which was symmetrical, the HOMO of the diene is higher in energy and now falls between the HOMO and LUMO of the dieneophile. This energetic similarity suggests a better interaction can be expected between the HOMO of the diene and the LUMO of the dieneophile than vica-versa, so this is an example of reverse electron demand, where an electron rich diene reacts with an electron poor dienophile. As before, bond formation is synchronous.

Nf710 (talk) 11:23, 12 January 2018 (UTC) You could have proven this with by running an energy calculation with both reactants on the same PES and looking at the orbitals.

(Fv611 (talk) As before, you didn't consider the relative energies of the TS MOs you computed, which would also have allowed you to expand your comparison between endo and exo case. Also note that the use of "symmetrical" in this phrasing "Another important observation is the relative energies of the diene and dienophile orbitals. compared to the previous case, which was symmetrical, the HOMO of the diene is higher in energy and now falls between the HOMO and LUMO of the dieneophile." is very unclear.)

|

The endo product

|

The exo product

| ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

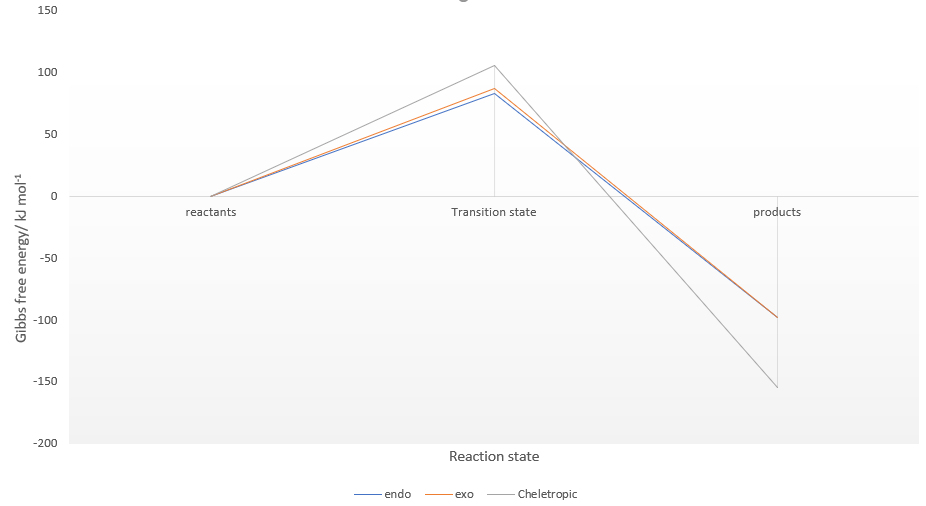

Reaction thermochemistry

Via computational methods, it is possible to investigate the changes in free energy between the reactants, the products and the transition states leading to their formation, enabling prediction of the thermodynamic and kinetic products, as discussed above. Presented below are the results of this calculation for this reaction. For the endo product, the TS energy is lower than the exo state, but the final energy of the products is not as low as that of the exo product. This has important implications, as the activation energy plays a fundamental role in describing the rate of a reaction, as given by the Arrhenius equation. Overall, this reaction can yield 2 products: If performed under kinetic conditions at cooler temperatures and for a shorter time, the endo product will dominate as the lower activation energy implies faster formation. However, if heated for an extended time-thermodynamic conditions-the products are allowed to equilibrate, and so a mixture of products will be formed, the majority being exo, as the rate of the reverse reaction here is lower than for endo.

| Activation energy | Reaction energy | |

|---|---|---|

| Endo- | 208.2 kJ/mol | -22.5 kJ/mol |

| Exo- | 216.1 kJ/mol | -23.7 kJ/mol |

LOGS:

Nf710 (talk) 11:29, 12 January 2018 (UTC)Sadly your energies are incorrect and you have therefore come to the wrong conclusion. I checked your files and you have ran them at the correct level of theory. SO I don't know how you calculated the energy differences. Furthermore your discussion is very brief. Your Diagrams are very good in your MO diagram however

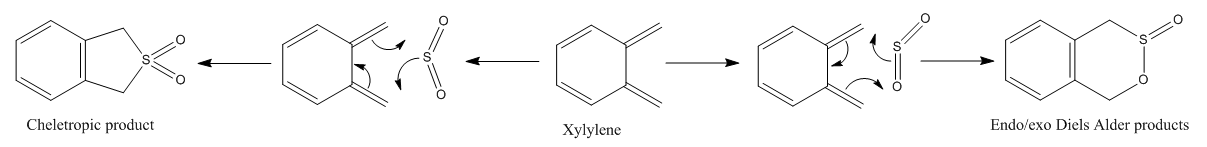

Diels-Alder vs Cheletropic chemistry

In the reaction of o-xylylene and sulfur dioxide, several competing reaction paths exist. As well as the endo and exo forms of the Diels-Alder, a third possibility exists in a cheletropic reaction in which only the sulfur centre is directly involved in the chemistry. The outcomes of the possible reactions are illustrated below. It is worth noting that o-xylylene itself is not a stable compound at room temperature, and to carry out this reaction in the laboratory this reagent would be produced in situ from benzocyclobutadiene. Unlike the previous reactions, bond formation here is not perfectly concerted in the cycloadditions, as the transition state does not have Cs symmetry, but is still pretty close, as evidenced in the reaction coordinates for these reactions.

This gives three possible reaction paths to consider! These are summarised in the table below.

| Product | Transition state | IRC | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endo |

| ||||||

| Exo |

| ||||||

| Cheletropic |

|

(In the table you state a reduction of steric hindrance as a reason for greater reactivity, but I would agree more with what you say below Tam10 (talk) 15:27, 9 January 2018 (UTC))

In all three reactions, the xylylene is aromatised, a significant stablising force in the reaction. Xylylene is unstable for precisely this reason; that it can spontaneously undergo an intramolecular reaction to form benzocyclobutadiene. To explain the greater stability of the cheletropic product, it is likely that the symmetry, lack of ring strain and absence of any lone pair on the S atom contribute to the overall extra stability of this product over the Diels-Alder adducts. The significant differences in activation energy and reaction energy here between products indicate that there is likely to be good selectivity observed under different conditions, kinetic probably yielding a mixture of endo and exo products, and thermodynamic giving a very good yield of the cheletropic product, it having a significantly more negative reaction energy.

LOGS:

Conclusion

In summary, in this article I have displayed some of the power of computational chemistry to examine chemical reactions. The processing power afforded by computers naturally lends itself to solving the immense numerical calculations required to model systems where analytical solution is impossible: the multinuclear molecules that comprise the majority of chemistry. In particular, the transient transition state can be probed at will to access information about its energy and structure.

In the example of the reaction of o-xylylene with sulfur dioxide I have shown how this can be the case, and how predictions about reactivity may be made on the basis of the computational model: a useful and cost-efficient approach when planning a synthetic sequence. As well as practical information, the theoretical reasons behind these observations can be elucidated using computational methods. In the example of the reaction of cyclohexadiene with 1,3-dioxole, the effect of the secondary orbital overlap can be imaged via MO calculations, and the additional positive orbital interactions of the endo state can be used to explain the lower activation energy of about 8 kJ/mol below the exo state. The concerted nature of the bond formation in all reactions can be seen, the key component of pericyclic reactions such as these, and may be contrasted between the strongly concerted reactions in the first two parts and the more asymmetric reactions in the third example.

Limitations of the methods used have also been exposed: although not displayed, several of the optimised structures given did not optimise to their most stable, and therefore probable, structures at the first attempt. A lot of nudging and repositioning was required to obtain the conformers shown: without a prior idea of what the transition state looks like, locating the optimised point is a great deal more difficult. Another issue encountered was the incorrect optimisation of the molecules involved. On occasion, despite a convincing structure, complete convergence in the log file and the expected number of negative frequencies observed, a more stable conformer was found to exist! This proved very important in part 2, as the exo conformer initially generated by the computer was more unstable both kinetically and thermodynamically, an unexpected result that was corrected by nudging the methylene group on the 1,3-dioxole derived part of the molecule. Despite these drawbacks, as computers get even more powerful it is likely they will take a greater role in chemistry, as the use of computational methods to plan reactions is cost efficient, time efficient, and the reduction in waste contributes to green chemistry.